Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward The Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders

Hochgeladen von

eriwirandana0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

426 Ansichten10 SeitenThe Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility, Economic, Legal, Ethical Components, Philanthropic Components, Stakeholders

Originaltitel

The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility, Economic, Legal, Ethical Components, Philanthropic Components, Stakeholders

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

426 Ansichten10 SeitenThe Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward The Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders

Hochgeladen von

eriwirandanaThe Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility, Economic, Legal, Ethical Components, Philanthropic Components, Stakeholders

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 10

The Pyramid of Corporate

Social Responsibility: Toward

the Moral Management of

Organizational Stakeholders

A r c h i e B. Car r ol l

F or t he bet t er part of 30 year s now, cor po-

rat e execut i ves have st r uggl ed wi t h t he

issue of t he fi rm' s responsi bi l i t y t o its soci-

ety. Early on it was ar gued by s ome t hat t he

cor por at i on' s sol e responsi bi l i t y was to pr ovi de a

ma x i mu m fi nanci al r et ur n t o shar ehol der s. It

be c a me qui ckl y a ppa r e nt to ever yone, however ,

t hat this pursui t of fi nanci al gai n had t o t ake

pl ace wi t hi n t he l aws of t he land. Though soci al

activist gr oups and ot her s t hr oughout t he 1960s

advocat ed a br oa de r not i on of cor por at e r es pon-

sibility, it was not until t he significant soci al legis-

l at i on of t he earl y 1970s t hat this mes s age be-

came i ndel i bl y cl ear as a resul t of t he cr eat i on of

t he Envi r onment al Pr ot ect i on Agency (EPA), t he

Equal Empl oyme nt Oppor t uni t y Commi ssi on

(EEOC), t he Occupat i onal Safety and Heal t h Ad-

mi ni st rat i on (OSHA), and t he Cons umer Pr oduct

Safety Commi ssi on (CPSC).

Thes e ne w gover nment al bodi es est abl i shed

t hat nat i onal publ i c pol i cy now officially r ecog-

ni zed t he envi r onment , empl oyees , and cons um-

ers to be significant and l egi t i mat e st akehol der s

of busi ness. Fr om t hat t i me on, cor por at e execu-

tives have had to wrest l e wi t h h o w t hey bal ance

t hei r commi t ment s to t he cor por at i on' s owner s

wi t h t hei r obl i gat i ons to an e ve >br oa de ni ng

gr oup of st akehol der s wh o cl ai m bot h legal and

et hi cal rights.

Thi s article will expl or e t he nat ur e of cor po-

rat e soci al responsi bi l i t y (CSR) wi t h an eye t o-

war d under s t andi ng its c o mp o n e n t parts. The

i nt ent i on will be to char act er i ze t he fi rm' s CSR in

ways t hat mi ght be useful to execut i ves wh o

wi sh t o r econci l e t hei r obl i gat i ons to t hei r share-

hol der s wi t h t hose t o

ot her compet i ng gr oups

cl ai mi ng l egi t i macy.

Thi s di scussi on will be

f r amed by a pyr ami d of

cor por at e soci al r es pon-

sibility. Next, we pl an

to rel at e this concept t o

t he i dea of st akehol d-

ers. Finally, our goal

will be to isolate t he

et hi cal or mor al c ompo-

nent of CSR and rel at e

it to per spect i ves t hat

S oc i al res pons i bi l i ty

c an onl y b ec o me

reafi ty i f mo r e man -

ager s b ec o me

mo r al i ns tead o f

amo r al or i mmoral .

reflect t hr ee maj or ethical a ppr oa c he s to manage-

me n t - i mmo r a l , amoral , and moral . The princi-

pal goal in this final sect i on will be to fl esh out

what it means t o ma na ge st akehol der s in an ethi-

cal or mor al fashi on.

E V OL U T I ON OF CORP ORAT E

S OCI AL RE S P ONS I B I L I T Y

Wp

hat does it me a n for a cor por at i on to

be soci al l y responsi bl e? Academi cs and

ract i t i oners have be e n striving to est ab-

lish an a gr e e d- upon defi ni t i on of this concept for

30 years. In 1960, Kei t h Davi s s ugges t ed t hat

social responsi bi l i t y refers t o busi nesses' "deci -

si ons and act i ons t aken for r easons at l east par-

tially be yond t he fi rm' s di rect economi c or t ech-

nical interest. " At about t he s ame time, Eells and

Wal t on (1961) ar gued t hat CSR refers to t he

"pr obl ems t hat arise wh e n cor por at e ent er pr i se

casts its s ha dow on t he soci al scene, and t he

The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responslblhty 39

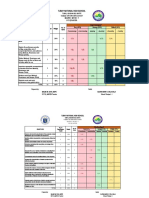

Fi gure 1

Ec o n o mi c a nd Legal Co mp o n e n t s o f Cor por at e Soci al Re s po ns i bi l i t y

Economic Components

(Responsibilities)

1. It is important to perform in a

manner consistent with

maximizing earnings per share.

2. It is irnportant to be committed to

being as profitable as possible.

3. It is important to maintain a strong

competitive position.

4. It is important to maintain a high

level of operating efficiency.

5 It is i mpor t a nt t hat a s ucces s f ul

f i r m b e de f i ne d as o n e t hat is

cons i s t ent l y pr of i t abl e.

2.

3.

5.

Legal Components

(Responsibilities)

It is important to perform in a

manner consistent with expecta-

tions of government and law.

It is i mpor t a nt t o c o mp l y wi t h

va r i ous f eder al , state, a nd l ocal

r egul at i ons.

It is important to be a law-abiding

corporate citizen.

It is important that a successful

firm be defined as one that fulfills

its legal obligations.

It is i mpor t a nt t o pr ovi de g o o d s

a nd s er vi ces t hat at l east me e t

mi ni ma l l egal r e qui r e me nt s .

ethical principles that ought to govern the rela-

tionship bet ween the corporation and society."

In 1971 the Committee for Economic Devel-

opment used a "three concentric circles" ap-

proach to depicting CSR. The inner circle in-

cluded basic economi c funct i ons--growt h, prod-

ucts, jobs. The intermediate circle suggested that

the economi c functions must be exercised with a

sensitive awareness of changing social values and

priorities. The outer circle outlined newly emerg-

ing and still amorphous responsibilities that busi-

ness should assume to become more actively

involved in improving the social environment.

The attention was shifted from social respon-

sibility to social responsiveness by several other

writers. Their basic argument was that the em-

phasis on responsibility focused exclusively on

the notion of business obligation and motivation

and that action or performance were being over-

looked. The social responsiveness movement,

therefore, emphasized corporate action, pro-

action, and implementation of a social role. This

was indeed a necessary reorientation.

The question still remained, however, of

reconciling the firm's economi c orientation with

its social orientation. A step in this direction was

taken when a comprehensive definition of CSR

was set forth. In this view, a four-part conceptu-

alization of CSR included the idea that the corpo-

ration has not only economi c and legal obliga-

tions, but ethical and discretionary (philan-

thropic) responsibilities as well (Carroll 1979).

The point here was that CSR, to be accepted as

legitimate, had to address the entire

spectrum of obligations business has to

society, including the most fundamen-

t al - economi c. It is upon this four-part

perspective that our pyramid is based.

in recent years, the term corporate

social performance (CSP) has emerged

as an inclusive and global concept to

embrace corporate social responsibility,

responsiveness, and the entire spectrum

of socially beneficial activities of busi-

nesses. The focus on social performance

emphasizes the concern for corporate

action and accomplishment in the social

sphere. With a performance perspective,

it is clear that firms must formulate and

implement social goals and programs as

well as integrate ethical sensitivity into

all decision making, policies, and ac-

tions. With a results focus, CSP suggests

an all-encompassing orientation towards

normal criteria by which we assess busi-

ness performance to include quantity,

quality, effectiveness, and efficiency.

While we recognize the vitality of the

performance concept, we have chosen

to adhere to the CSR terminology for our

present discussion. With just a slight change of

focus, however, we could easily be discussing a

CSP rather than a CSR pyramid. In any event, our

long-term concern is what managers do with

these ideas in terms of implementation.

THE PYRAMID OF CORPORATE

SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

F or CSR to be accepted by a conscientious

business person, it should be framed in

such a way that the entire range of busi-

ness responsibilities are embraced. It is suggested

here that four kinds of social responsibilities con-

stitute total CSR: economic, legal, ethical, and

philanthropic. Furthermore, these four categories

or component s of CSR might be depicted as a

pyramid. To be sure, all of these kinds of respon-

sibilities have always existed to some extent, but

it has only been in recent years that ethical and

philanthropic functions have taken a significant

place. Each of these four categories deserves

closer consideration.

Ec o no mi c Res pons i bi l i t i es

Historically, business organizations were created

as economi c entities designed to provide goods

and services to societal members. The profit mo-

tive was established as the primary incentive for

entrepreneurship. Before it was anything else, the

business organization was the basic economi c

unit in our society. As such, its principal role was

40 Business Horizons /July-August 1991

to produce goods and services that con-

sumers needed and want ed and to make

an acceptable profit in the process. At

some point the idea of the profit motive

got transformed into a notion of maxi mum

profits, and this has been an enduring

value ever since. All other business re-

sponsibilities are predicated upon the eco-

nomic responsibility of the firm, because

without it the others become moot consid-

erations. Fi gur e 1 summarizes some im-

portant statements characterizing economi c

responsibilities. Legal responsibilities are

also depicted in Figure 1, and we will

consider them next.

Legal Responsibilities

Figure 2

Ethical and Philanthropic Components of

Corporate Social Responsibility

1.

2.

3.

Society has not only sanctioned business

to operate according to the profit motive;

at the same time business is expected to

compl y with the laws and regulations pro-

mulgated by federal, state, and local gov-

ernments as the ground rules under whi ch

business must operate. As a partial fulfill-

ment of the "social contract" bet ween busi-

ness and society, firms are expected to

pursue their economi c missions within the

framework of the law. Legal responsibili-

ties reflect a view of "codified ethics" in

the sense that they embody basic notions

of fair operations as established by our lawmak-

ers. They are depicted as the next layer on the

pyramid to portray their historical development,

but they are appropriately seen as coexisting with

economi c responsibilities as fundamental pre-

cepts of the free enterprise system.

Ethical Responsibilities

Although economi c and legal responsibilities

embody ethical norms about fairness and justice,

ethical responsibilities embrace those activities

and practices that are expected or prohibited by

societal members even t hough they are not codi-

fied into law. Ethical responsibilities embody

those standards, norms, or expectations that re-

flect a concern for what consumers, employees,

shareholders, and the communi t y regard as fair,

just, or in keeping with the respect or protection

of stakeholders' moral rights.

In one sense, changing ethics or values pre-

cede the establishment of law because they be-

come the driving force behind the very creation

of laws or regulations. For example, the environ-

mental, civil rights, and consumer movement s

reflected basic alterations in societal values and

thus may be seen as ethical bellwethers foreshad-

owing and resulting in the later legislation. In

another sense, ethical responsibilities may be

Ethical Components

(Responsibilities)

It is important to perform in a

manner consistent with expecta-

tions of societal mores and ethical

norms.

It is important to recognize and

respect new or evolving ethical/

moral norms adopted by society.

It is important to prevent ethical

norms from being compromised in

order to achieve corporate goals.

4. It is important that good corporate

citizenship be defined as doing what

is expected morally or ethically.

5. It is important to recognize that

corporate integrity and ethical

behavior go beyond mere compli-

ance with laws and regulations.

3.

4.

5.

Philanthropic Components

(Responsibilities)

It is tmportant to perform in a

manner consistent with the philan-

thropic and charitable expectations

of society.

It is important to assist the fine and

performing arts.

It is important that managers and

employees participate in voluntary

and charitable activities within their

local communities.

It is important to provide assis-

tance to private and public educa-

tional institutions.

It is important to assist voluntarily

those projects that enhance a

community's "quality of life."

seen as embracing newl y emerging values and

norms society expects business to meet, even

t hough such values and norms may reflect a

higher standard of performance than that cur-

rently required by law. Ethical responsibilities in

this sense are often ill-defined or continually

under public debate as to their legitimacy, and

thus are frequently difficult for business to deal

with.

Superimposed on these ethical expectations

emanating from societal groups are the implied

levels of ethical performance suggested by a

consideration of the great ethical principles of

moral philosophy. This woul d include such prin-

ciples as justice, rights, and utilitarianism.

The business ethics movement of the past

decade has firmly established an ethical responsi-

bility as a legitimate CSR component . Though it is

depicted as the next layer of the CSR pyramid, it

must be constantly recognized that it is in dy-

namic interplay with the legal responsibility cat-

egory. That is, it is constantly pushing the legal

responsibility category to broaden or expand

while at the same time placing ever higher ex-

pectations on businesspersons to operate at lev-

els above that required by law. Fi gur e 2 depicts

statements that help characterize ethical responsi-

bilities. The figure also summarizes philanthropic

responsibilities, discussed next.

The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responslblli W 41

Figure 3

The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility

PHILANTHROPIC

Responsibilities \

Be a good corporate c i t i z e n . \

Contribute resources \

to the community; \

improve quality of life. \

ETHICAL

Responsibilities

Be ethical.

Obligation to do what is right, just, \

and fair. Avoid harm.

LEGAL

Responsibilities

Obey the law. , \

Law is society's codification of right and wrong. \

Play by the rules of the g a m e . ~

ECONOMIC

Responsibilities

Be profitable.

The foundation upon which all others rest. \

\

Philanthropic Responsibilities

Phi l ant hr opy e nc ompa s s e s t hose cor por at e ac-

t i ons t hat are in r es pons e t o soci et y' s expect at i on

t hat busi nesses be good cor por at e citizens. Thi s

i ncl udes act i vel y engagi ng in acts or pr ogr ams to

pr omot e huma n wel f ar e or goodwi l l . Exampl es of

phi l ant hr opy i ncl ude busi ness cont r i but i ons of

fi nanci al r esour ces or execut i ve time, such as

cont r i but i ons to t he arts, educat i on, or t he com-

muni t y. A l oaned- execut i ve pr ogr a m t hat pr o-

vi des l eader shi p for a communi t y' s Uni t ed Way

campai gn is one illustration of phi l ant hr opy.

The di st i ngui shi ng feat ure be t we e n phi l an-

t hr opi c and et hi cal responsi bi l i t i es is t hat t he

f or mer are not expect ed in an et hi cal or mor al

sense. Communi t i es desi re firms to cont r i but e

t hei r money, facilities, and e mpl oye e t i me t o

humani t ar i an pr ogr ams or pur pos es , but t hey do

not r egar d t he firms as unet hi cal if t hey do not

pr ovi de t he desi r ed level. Ther ef or e, phi l an-

t hr opy is mor e di scr et i onar y or vol unt ar y on t he

part of busi nesses even t hough t her e is

al ways t he soci et al expect at i on t hat busi -

nesses pr ovi de it.

One not abl e r eas on for maki ng t he dis-

t i nct i on be t we e n phi l ant hr opi c and ethical

responsi bi l i t i es is t hat s ome firms feel t hey

are bei ng soci al l y r esponsi bl e if t hey are

just good citizens in t he communi t y. Thi s

di st i nct i on bri ngs h o me t he vital poi nt t hat

CSR i ncl udes phi l ant hr opi c cont r i but i ons

but is not l i mi t ed to t hem. I n fact, it woul d

be ar gued her e t hat phi l ant hr opy is hi ghl y

desi r ed and pr i zed but act ual l y less i mpor -

t ant t han t he ot her t hr ee cat egor i es of social

responsi bi l i t y. I n a sense, phi l ant hr opy is

icing on t he c a k e - - o r on t he pyr ami d, us-

ing our met aphor .

The pyr ami d of cor por at e soci al r espon-

sibility is depi ct ed in Fi g u r e 3. It port rays

t he four c ompone nt s of CSR, begi nni ng

wi t h t he basi c bui l di ng bl ock not i on t hat

economi c per f or mance under gi r ds all else.

At t he s ame t i me, busi ness is expect ed t o

obe y t he l aw becaus e t he l aw is soci et y' s

codi fi cat i on of accept abl e and unaccept abl e

behavi or . Next is busi ness' s responsi bi l i t y to

be ethical. At its mos t f undament al level,

this is t he obl i gat i on to do what is right,

just, and fair, and to avoi d or mi ni mi ze

har m to st akehol der s ( empl oyees , cons um-

ers, t he envi r onment , and ot hers). Finally,

busi ness is e xpe c t e d to be a good cor po-

rat e citizen. This is capt ur ed in t he phi l an-

t hr opi c responsi bi l i t y, wher ei n busi ness is

e xpe c t e d t o cont r i but e fi nanci al and h u ma n

r esour ces t o t he c ommuni t y and to i mpr ove

t he qual i t y of life.

No me t a phor is perfect , and t he CSR

pyr ami d is no except i on. It is i nt ended t o por t r ay

t hat t he total CSR of busi ness compr i s es distinct

c ompone nt s that, t aken t oget her, const i t ut e t he

whol e. Though t he c ompone nt s have be e n

t r eat ed as separ at e concept s for di scussi on pur-

poses, t hey are not mut ual l y excl usi ve and are

not i nt ended to j uxt apose a fi rm' s economi c re-

sponsi bi l i t i es wi t h its ot her responsibilities. At t he

s ame time, a consi der at i on of t he separ at e com-

ponent s hel ps t he ma na ge r see t hat t he di fferent

t ypes of obl i gat i ons are in a const ant but dy-

nami c t ensi on wi t h one anot her. The mos t critical

t ensi ons, of course, woul d be be t we e n economi c

and legal, economi c and ethical, and economi c

and phi l ant hropi c. The traditionalist mi ght see

this as a conflict be t we e n a fi rm' s "concer n for

profits" ver sus its "concer n for society, " but it is

s ugges t ed her e t hat this is an oversi mpl i fi cat i on.

A CSR or s t akehol der per spect i ve woul d r ecog-

ni ze t hese t ensi ons as or gani zat i onal realities, but

focus on t he total pyr ami d as a uni fi ed whol e

and h o w t he fi rm mi ght engage in deci si ons,

42 Business Horizons /July-August 199

actions, and pr ogr ams t hat si mul t aneousl y fulfill

all its c o mp o n e n t parts.

I n s ummar y, t he total cor por at e soci al re-

sponsi bi l i t y of busi ness entails t he si mul t aneous

fulfillment of t he fi rm' s economi c, legal, ethical,

and phi l ant hr opi c responsi bi l i t i es. Stated in mor e

pr agmat i c and manager i al t erms, t he CSR fi rm

shoul d strive to ma ke a profit, o b e y t he law, be

ethical, and be a good cor por at e citizen.

Upon first gl ance, this array of responsi bi l i -

ties ma y s e e m br oad. They s e e m to be in st ri ki ng

cont rast to t he classical e c onomi c ar gument t hat

ma na ge me nt has one responsi bi l i t y: t o maxi mi ze

t he profits of its owner s or shar ehol der s. Econo-

mi st Milton Fr i edman, t he mos t out s poke n pr opo-

nent of this vi ew, has ar gued t hat soci al mat t ers

are not t he concer n of busi ness pe opl e and t hat

t hese pr obl ems shoul d be r esol ved by t he

unf et t er ed wor ki ngs of t he free mar ket syst em.

Fr i edman' s ar gument l oses s ome of its punch,

however , wh e n you consi der his asser t i on in its

totality. Fr i edman posi t ed t hat ma na ge me nt is "'to

ma ke as muc h mo n e y as possi bl e whi l e conf or m-

ing to t he basi c rul es of soci et y, bot h t hose em-

bodi e d in t he l aw and t hose e mb o d i e d in et hi cal

cust om" ( Fr i edman 1970). Most pe opl e focus on

t he first par t of Fr i edman' s quot e but not t he

s econd part. It s eems cl ear f r om this st at ement

t hat profits, conf or mi t y to t he law, and et hi cal

cus t om e mbr a c e t hr ee c ompone nt s of t he CSR

pyr a mi d- - e c onomi c , legal, and ethical. That onl y

l eaves t he phi l ant hr opi c c o mp o n e n t for Fr i edman

to reject. Al t hough it ma y be appr opr i at e for an

economi s t to t ake this vi ew, one woul d not en-

count er ma n y busi ness execut i ves t oday wh o

excl ude phi l ant hr opi c pr ogr ams f r om t hei r fi rms'

r ange of activities. It s eems t he rol e of cor por at e

ci t i zenshi p is one t hat busi ness has no significant

pr obl e m embr aci ng. Undoubt edl y this per s pec-

tive is rat i onal i zed under t he rubri c of enl i ght -

ened sel f interest.

We next pr opos e a concept ual f r a me wor k to

assist t he ma na ge r in i nt egrat i ng t he f our CSR

c ompone nt s wi t h or gani zat i onal st akehol der s.

CSR AND ORGANIZATIONAL STAKEHOLDERS

T h e r e is nat ural fit be t we e n t he i dea of

a

cor por at e soci al r esponsi bi l i t y and an

or gani zat i on s st akehol der s. The wor d

"social" in CSR has al ways b e e n vague and l ack-

ing in speci fi c di rect i on as to wh o m t he cor por a-

t i on is r esponsi bl e. The c onc e pt of s t akehol der

per sonal i zes soci al or soci et al responsi bi l i t i es by

del i neat i ng t he speci fi c gr oups or per s ons busi -

ness s houl d consi der in its CSR ori ent at i on. Thus,

t he s t akehol der nomencl at ur e put s "names and

faces" on t he soci et al me mb e r s wh o are mos t

ur gent t o busi ness, and t o wh o m it mus t be re-

sponsi ve.

By n o w mos t execut i ves under s t and t hat t he

t er m "st akehol der" const i t ut es a pl ay on t he wor d

st ockhol der and is i nt ended t o mor e appr opr i -

at el y descr i be t hose gr oups or per s ons wh o have

a st ake, a claim, or an i nt erest in t he oper at i ons

and deci si ons of t he firm. Somet i mes t he st ake

mi ght r epr es ent a l egal claim, such as t hat whi ch

mi ght be hel d by an owner , an empl oyee, or a

cus t omer wh o has an expl i ci t or implicit cont ract .

Ot her t i mes it mi ght be r epr es ent ed by a mor al

claim, such as wh e n t hese gr oups assert a right to

be t r eat ed fairly or wi t h due pr ocess, or t o have

t hei r opi ni ons t aken i nt o consi der at i on in an

i mpor t ant busi ness deci si on.

Management ' s chal l enge is to deci de whi ch

st akehol der s meri t and r ecei ve consi der at i on in

t he deci si on- maki ng process. In any gi ven in-

st ance, t her e ma y be nume r ous st akehol der

gr oups ( shar ehol der s, consumer s, empl oyees ,

suppl i ers, communi t y, soci al activist gr oups )

cl amor i ng for ma na ge me nt ' s attention. Ho w do

manager s sort out t he ur gency or i mpor t ance of

t he var i ous st akehol der claims? Two vital criteria

i ncl ude t he st akehol der s' l egi t i macy and t hei r

power . Fr om a CSR per s pect i ve t hei r l egi t i macy

ma y be mos t i mport ant . Fr om a ma na ge me nt

effi ci ency per spect i ve, t hei r p o we r mi ght be of

cent ral i nfl uence. Legi t i macy refers t o t he ext ent

to whi ch a gr oup has a justifiable right t o be

maki ng its claim. For exampl e, a gr oup of 300

e mpl oye e s about t o be laid off b y a pl ant -cl osi ng

deci si on has a mor e l egi t i mat e cl ai m on ma na ge -

ment ' s at t ent i on t han t he local c ha mbe r of com-

mer ce, whi ch is wor r i ed about l osi ng t he fi rm as

one of its dues - payi ng member s . The st ake-

hol der ' s p o we r is anot her factor. Her e we ma y

wi t ness significant di fferences. Thous ands of

small, i ndi vi dual i nvest ors, for exampl e, wi el d

ver y little p o we r unl ess t hey can fi nd a wa y to

get organi zed. By contrast, institutional i nvest ors

and large mut ual f und gr oups have significant

p o we r over ma n a g e me n t becaus e of t he sheer

magni t ude of t hei r i nvest ment s and t he fact t hat

t hey are organi zed.

With t hese per spect i ves in mi nd, let us t hi nk

of st akehol der ma na ge me nt as a pr ocess by

whi ch manager s r econci l e t hei r o wn obj ect i ves

wi t h t he cl ai ms and expect at i ons bei ng ma de on

t hem by var i ous s t akehol der groups. The chal-

l enge of s t akehol der ma n a g e me n t is t o ensur e

t hat t he fi rm' s pr i mar y st akehol der s achi eve t hei r

obj ect i ves whi l e ot her st akehol der s are al so satis-

fied. Even t hough this "wi n-wi n" out c ome is not

al ways possi bl e, it does r epr es ent a l egi t i mat e

and desi r abl e goal for ma na ge me nt to pur s ue to

pr ot ect its l ong- t er m interests.

The i mpor t ant f unct i ons of s t akehol der man-

a ge me nt are to descri be, under st and, anal yze,

and finally, manage. Thus, five maj or quest i ons

mi ght be pos e d to capt ur e t he essent i al i ngredi -

The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibdlty 43

Fi gur e 4

S t a k e h o l d e r / Re s p o n s i b i l i t y Mat r i x

Types of CSR

Stakeholders Economic Legal Ethical Philanthropic

Owners

Customers

Employees

Community

Competitors

Suppliers

Social Activist Groups

Public at Large

Others

ent s we ne e d for st akehol der management :

1. Who are our st akehol ders?

2. What are t hei r stakes?

3. What oppor t uni t i es and chal l enges are

pr es ent ed by our st akehol ders?

4. What cor por at e social responsi bi l i t i es ( eco-

nomi c, legal, ethical, and phi l ant hr opi c) do we

have to our st akehol ders?

5. What strategies, actions, or deci si ons

s houl d we t ake t o best deal wi t h t hese r esponsi -

bilities?

Wher eas muc h coul d be di scussed about

each of t hese quest i ons, let us di rect our at t en-

t i on her e t o quest i on f o u r - - wh a t ki nds of social

responsi bi l i t i es do we have to our st akehol ders?

Our obj ect i ve her e is to pr esent a concept ual

a ppr oa c h for exami ni ng t hese issues. Thi s con-

cept ual a ppr oa c h or f r a me wor k is pr es ent ed as

t he st akehol der / r esponsi bi l i t y mat ri x in Fi g u r e 4.

This mat ri x is i nt ended to be us ed as an ana-

lytical t ool or t empl at e to organi ze a manager ' s

t hought s and i deas about what t he fi rm ought to

be doi ng in an economi c, legal, ethical, and phi l -

ant hr opi c sense wi t h r espect t o its i dent i fi ed

st akehol der gr oups. By careful l y and del i ber at el y

movi ng t hr ough t he var i ous cells of t he matrix,

t he ma na ge r ma y devel op a significant descri p-

tive and analytical dat a bas e t hat can t hen be

us ed for pur pos es of s t akehol der management .

The i nf or mat i on resul t i ng f r om this s t akehol der /

responsi bi l i t y anal ysi s shoul d be useful wh e n

devel opi ng priorities and maki ng bot h l ong- t er m

and shor t - t er m deci si ons i nvol vi ng mul t i pl e

st akehol der ' s interests.

To be sure, t hi nki ng in st akehol der -

responsi bi l i t y t er ms i ncreases t he com-

pl exi t y of deci si on maki ng and ma y be

ext r emel y t i me cons umi ng and taxing,

especi al l y at first. Despi t e its compl exi t y,

however , this a ppr oa c h is one met hodol -

ogy ma na ge me nt can use to i nt egrat e val-

u e s - wh a t it st ands f or - - wi t h t he tradi-

t i onal economi c mi ssi on of t he organi za-

tion. In t he final analysis, such an i nt egra-

t i on coul d be of significant usef ul ness t o

management . Thi s is becaus e t he st ake-

hol der / r esponsi bi l i t y per spect i ve is mos t

consi st ent wi t h t he pluralistic envi r onment

f aced by busi ness t oday. As such, it pr o-

vi des t he oppor t uni t y for an i n- dept h cor-

por at e appr ai sal of fi nanci al as wel l as

social and economi c concer ns. Thus, t he

st akehol der / r esponsi bi l i t y per spect i ve

woul d be an i nval uabl e f oundat i on for

r es pondi ng to t he fifth st akehol der man-

a ge me nt quest i on about strategies, actions,

or deci si ons t hat shoul d be pur s ued t o

effect i vel y r e s pond to t he envi r onment

busi ness faces.

MORAL MANAGEMENT AND

STAKEHOLDERS

A

t this j unct ure we woul d like to e x p o u n d

u p o n t he link be t we e n t he fi rm' s et hi cal

responsi bi l i t i es or per spect i ves and its

maj or s t akehol der gr oups. Her e we are i sol at i ng

t he et hi cal c o mp o n e n t of our CSR pyr ami d and

di scussi ng it mor e t hor oughl y in t he cont ext of

st akehol der s. One wa y t o do this woul d be to

use maj or et hi cal pr i nci pl es such as t hose of jus-

tice, rights, and utilitarianism to i dent i fy and de-

scri be our et hi cal responsi bi l i t i es. We will t ake

anot her al t ernat i ve, however , and di scuss st ake-

hol der s wi t hi n t he cont ext of t hree maj or ethical

a p p r o a c h e s - - i mmo r a l management , amor al man-

agement , and mor al management . Thes e t hr ee

ethical a ppr oa c he s wer e def i ned and di scussed in

an earlier Business Horizons article (Carroll 1987).

We will bri efl y descr i be and r evi ew t hese t hree

ethical t ypes and t hen suggest h o w t hey mi ght be

or i ent ed t owar d t he maj or st akehol der groups.

Our goal is t o profi l e t he likely or i ent at i on of t he

t hr ee et hi cal t ypes wi t h a speci al emphas i s u p o n

mor al management , our pr ef er r ed et hi cal ap-

pr oach.

Thr e e Mor al Type s

If we accept t hat t he t er ms et hi cs and moral i t y

are essent i al l y s ynonymous in t he organi zat i onal

cont ext , we ma y s pe a k of i mmoral , amoral , and

mor al ma na ge me nt as descr i pt i ve cat egor i es of

t hr ee di fferent ki nds of manager s. I mmor al man-

44 Business Horizons /July-August 1991

a ge me nt is char act er i zed by t hose manager s

whos e deci si ons, act i ons, and behavi or suggest

an act i ve oppos i t i on t o what is d e e me d right or

ethical. Deci si ons by i mmor al manager s are dis-

cor dant wi t h accept ed ethical pri nci pl es and,

i ndeed, i mpl y an act i ve negat i on of what is

moral . These manager s care onl y about t hei r or

t hei r or gani zat i on' s profi t abi l i t y and success. They

see l egal st andar ds as barri ers or i mpedi ment s

ma na ge me nt mus t ove r c ome to accompl i s h what

it want s. Thei r st rat egy is t o expl oi t oppor t uni t i es

for per s onal or cor por at e gain.

An e xa mpl e mi ght be hel pful . Many obser v-

ers woul d ar gue t hat Charl es Keat i ng coul d be

descr i bed as an i mmor al manager . Accor di ng to

t he federal gover nment , Keat i ng r eckl essl y and

f r audul ent l y ran Cal i forni a' s Lincoln Savings i nt o

t he gr ound, r eapi ng $34 mi l l i on for hi msel f and

his family. A maj or account i ng fi rm sai d about

Keating: "Sel dom in our exper i ence as accoun-

t ant s have we exper i enced a mor e egr egi ous

e xa mpl e of t he mi sappl i cat i on of gener al l y ac-

cept ed account i ng pri nci pl es" ( " Good Ti mi ng,

Charlie" 1989).

The s econd maj or t ype of ma n a g e me n t et hi cs

is amor al management . Amor al manager s are

nei t her i mmor al nor mor al but are not sensi t i ve

to t he fact t hat t hei r ever yday busi ness deci si ons

ma y have del et er i ous effect s on others. Thes e

manager s l ack et hi cal per cept i on or awar eness.

That is, t hey go t hr ough t hei r or gani zat i onal lives

not t hi nki ng t hat t hei r act i ons have an ethical

di mensi on. Or t hey ma y just be carel ess or inat-

t ent i ve to t he i mpl i cat i ons of t hei r act i ons on

st akehol der s. Thes e manager s ma y be wel l

i nt ent i oned, but do not see t hat t hei r busi ness

deci si ons and act i ons ma y be hurt i ng t hose wi t h

wh o m t hey t ransact busi ness or interact. Typi cal l y

t hei r or i ent at i on is t owar ds t he letter of t he l aw

as t hei r et hi cal gui de. We have b e e n descr i bi ng a

s ub- cat egor y of amor al i t y k n o wn as uni nt ent i onal

amor al manager s. Ther e is al so anot her gr oup we

ma y call i nt ent i onal amor al manager s. Thes e

manager s si mpl y t hi nk t hat et hi cal consi der at i ons

are for our pri vat e lives, not for busi ness. They

bel i eve t hat busi ness activity resi des out si de t he

s pher e to whi ch mor al j udgment s appl y. Though

mos t amor al manager s t oday are uni nt ent i onal ,

t her e ma y still exi st a f ew wh o just do not see a

rol e for et hi cs in busi ness.

Exampl es of uni nt ent i onal amor al i t y abound.

When pol i ce depar t ment s st i pul at ed t hat appl i -

cant s must be 5'10" and wei gh 180 pounds to

qual i fy for posi t i ons, t hey just di d not t hi nk about

t he adver se i mpact t hei r pol i cy woul d have on

wo me n and s ome et hni c gr oups who, on aver-

age, do not attain t hat hei ght and wei ght . The

liquor, beer, and ci garet t e i ndust ri es pr ovi de

ot her exampl es . They di d not ant i ci pat e t hat t hei r

pr oduct s woul d creat e seri ous mor al issues: al co-

hol i sm, dr unk dri vi ng deat hs, l ung cancer, det e-

ri orat i ng heal t h, and of f ensi ve s econdar y smoke.

Finally, wh e n McDonal d' s initially deci ded to use

pol ys t yr ene cont ai ner s for f ood packagi ng it just

di d not adequat el y consi der t he envi r onment al

i mpact t hat woul d be caused. McDonal d' s surel y

does not i nt ent i onal l y creat e a sol i d was t e dis-

posal pr obl em, but one maj or cons equence of its

busi ness is just that. Fort unat el y, t he c o mp a n y

has r e s ponde d to compl ai nt s by r epl aci ng t he

pol ys t yr ene packagi ng wi t h pa pe r product s.

Moral ma na ge me nt is our third et hi cal ap-

pr oach, one t hat shoul d pr ovi de a st ri ki ng con-

trast. I n mor al management , ethical nor ms t hat

adher e t o a hi gh st andar d of right behavi or are

empl oyed. Moral manager s not onl y conf or m to

accept ed and hi gh l evel s of pr of essi onal conduct ,

t hey al so c ommonl y exempl i f y l eader shi p on

ethical issues. Moral manager s want to be profit-

able, but onl y wi t hi n t he confi nes of s ound l egal

and ethical pr ecept s, such as fairness, justice, and

due process. Under this appr oach, t he or i ent at i on

is t owar d bot h t he l et t er and t he spirit of t he law.

Law is s een as mi ni mal et hi cal behavi or and t he

pr ef er ence and goal is to oper at e wel l a bove

what t he l aw mandat es. Moral manager s s eek out

and use s ound et hi cal pr i nci pl es such as justice,

rights, utilitarianism, and t he Gol den Rule to

gui de t hei r deci si ons. Whe n et hi cal di l emmas

arise, mor al manager s as s ume a l eader shi p posi -

t i on for t hei r compani es and industries.

Ther e are nume r ous exampl es of mor al man-

agement . Whe n IBM t ook t he l ead and devel -

ope d its Op e n Door pol i cy t o pr ovi de a mecha-

ni sm t hr ough whi ch e mpl oye e s mi ght pur s ue

t hei r due pr ocess rights, this coul d be cons i der ed

mor al management . Similarly, wh e n IBM initiated

its Four Pri nci pl es of Pri vacy to pr ot ect pr i vacy

rights of empl oyees , this was mor al management .

Whe n McCul l ough Cor por at i on wi t hdr ew f r om

t he Chai n Saw Manufact urers Associ at i on becaus e

t he associ at i on f ought ma nda t or y safet y st andar ds

for t he industry, this was mor al management .

McCul l ough k n e w its pr oduct was pot ent i al l y

danger ous and had us ed chai n br akes on its own

saws for years, even t hough it was not r equi r ed

b y l aw to do so. Anot her e xa mpl e of mor al man-

a ge me nt was wh e n Magui re Thoma s Part ners, a

Los Angel es commer ci al devel oper , he l pe d sol ve

ur ban pr obl ems by savi ng and refurbi shi ng his-

toric sites, put t i ng up st ruct ures t hat mat ched ol d

ones, limiting bui l di ng hei ght s to tess t han t he

l aw al l owed, and usi ng onl y t wo-t hi rds of t he

al l owabl e bui l di ng densi t y so t hat o p e n spaces

coul d be pr ovi ded.

O r i e n t a t i o n T o w a r d S t a k e h o l d e r s

Now t hat we have a basi c under s t andi ng of t he

t hr ee et hi cal t ypes or appr oaches , we will pr o-

The Pyramid of Corporate Sooal Responslbdlty 45

p o s e pr of i l e s o f wh a t t he l i ke l y s t a k e h o l d e r or i -

e n t a t i o n mi g h t b e t o wa r d t he ma j o r s t a k e h o l d e r

g r o u p s us i ng e a c h of t he t hr e e e t hi c a l a p -

p r o a c h e s . Ou r g o a l is t o a c c e n t u a t e t he mo r a l

ma n a g e me n t a p p r o a c h b y c o n t r a s t i n g it wi t h t he

o t h e r t wo t ype s .

Bas i cal l y, t h e r e a r e f i ve ma j o r s t a k e h o l d e r

g r o u p s t hat a r e r e c o g n i z e d as pr i or i t i e s b y mo s t

f i r ms, a c r os s i n d u s t r y l i nes a n d i n s pi t e o f si ze o r

l oc a t i on: o wn e r s ( s h a r e h o l d e r s ) , e mp l o y e e s , cus -

t ome r s , l oc a l c o mmu n i t i e s , a n d t he s oc i e t y- a t -

l ar ge. Al t h o u g h t he g e n e r a l e t hi c a l o b l i g a t i o n t o

e a c h o f t h e s e g r o u p s is e s s e nt i a l l y i de nt i c a l ( pr o-

t ect t he i r r i ght s, t r eat t h e m wi t h r e s p e c t a n d f ai r -

nes s ) , s pe c i f i c b e h a v i o r s a n d o r i e n t a t i o n s ar i s e

b e c a u s e o f t he di f f er i ng n a t u r e o f t he g r o u p s . I n

a n a t t e mp t t o f l es h o u t t he c h a r a c t e r a n d s a l i e nt

f e a t ur e s of t he t h r e e e t hi c a l t y p e s a n d t he i r s t a ke -

h o l d e r or i e nt a t i ons , F i g u r e s 5 a n d 6 s u mma r i z e

t he o r i e n t a t i o n s t h e s e t h r e e t y p e s mi ght a s s u me

wi t h r e s p e c t t o f our of t he ma j o r s t a k e h o l d e r

g r o u p s . Be c a u s e o f s p a c e c ons t r a i nt s a n d t he

g e n e r a l n a t u r e of t he s oc i e t y- a t - l a r ge c a t e gor y, i t

ha s b e e n omi t t e d.

Fi gure 5

Three Moral Types and Ori ent at i on Toward

St akehol der Groups: Owners and Empl oyees

Type of Management

Immoral Management

Amoral Management

Orientation Toward Owner~Shareholder Stakeholders

Sharehol ders are mi ni mal l y t reat ed and gi ven short shrift. Focus is on

maxi mi zi ng posi t i ons of execut i ve gr oups- - - maxi mi zi ng execut i ve com-

pensat i on, perks, benefits. Gol den parachut es are mor e i mpor t ant t han

ret urns to sharehol ders. Managers maxi mi ze t hei r posi t i ons wi t hout share-

hol ders bei ng made aware. Conceal ment from shar ehol der s is t he oper at -

ing pr ocedur e. Self-interest of management gr oup is t he or der of t he day.

No speci al t hought is gi ven to sharehol ders; t hey are t here and must be

mi ni mal l y accommodat ed. Profit focus of t he busi ness is t hei r reward. No

t hought is gi ven to ethical consequences of deci si ons for any st akehol der

group, i ncl udi ng owners. Communi cat i on is l i mi t ed to that r equi r ed by

law.

Moral Management Sharehol ders' i nt erest (short- and l ong-t erm) is a central factor. The best

way to be ethical to shar ehol der s is to treat all st akehol der claimants in a

fair and ethical manner. To prot ect sharehol ders, an ethics commi t t ee of

t he boar d is created. Code of ethics is est abl i shed, pr omul gat ed, and made

a living document to prot ect shar ehol der s' and ot hers' interests.

Type of Management

Immoral Management

Amoral Management

Moral Management

Orientation Toward Employee Stakeholders

Empl oyees are vi ewed as factors of pr oduct i on to be used, expl oi t ed,

mani pul at ed for gai n of i ndi vi dual manager or company. No concer n is

shown for empl oyees ' needs/ r i ght s/ expect at i ons. Short-term focus. Coer-

cive, controlling, alienating.

Empl oyees are t r eat ed as l aw requires. At t empt s to mot i vat e focus on

i ncreasi ng product i vi t y rather t han satisfying empl oyees ' gr owi ng mat uri t y

needs. Empl oyees still seen as factors of pr oduct i on but remunerat i ve

appr oach used. Organi zat i on sees self-interest in treating empl oyees wi t h

mi ni mal respect. Organi zat i on structure, pay incentives, r ewar ds all gear ed

t owar d short- and medi um- t er m productivity.

Empl oyees are a human resource that must be t reat ed wi t h di gni t y and

respect. Goal is to use a l eader shi p style such as consul t at i ve/ part i ci pat i ve

that will result in mut ual conf i dence and trust. Commi t ment is a recurri ng

theme. Empl oyees' rights to due process, privacy, f r eedom of speech, and

safety are maxi mal l y consi der ed in all deci si ons. Management seeks out

fair deal i ngs wi t h empl oyees.

i6 Business Horizons / July-August 1991

By car ef ul l y c ons i de r i ng t he de s c r i be d st ake-

hol de r or i ent at i ons u n d e r e a c h of t he t hr ee et hi -

cal t ypes, a r i cher a ppr e c i a t i on o f t he mor a l ma n -

a g e me n t a p p r o a c h s h o u l d be possi bl e. Ou r goa l

he r e is t o gai n a ful l er u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f wh a t it

me a n s t o e n g a g e i n mor a l ma n a g e me n t a n d wh a t

t hi s i mpl i es f or i nt er act i ng wi t h s t akehol der s . To

be sur e, t her e ar e ot he r s t a ke hol de r g r o u p s t o

wh i c h mor a l ma n a g e me n t s h o u l d be di r ect ed, but

agai n, s pa c e pr e c l ude s t hei r di s cus s i on her e. Thi s

mi ght i ncl ude t hi nki ng o f ma n a g e r s a n d n o n -

ma n a g e r s as di st i nct cat egor i es o f e mp l o y e e s a n d

wo u l d al so e mb r a c e s uc h g r o u p s as suppl i er s,

compet i t or s , s peci al i nt er est gr oups , g o v e r n me n t ,

a n d t he medi a.

T

h o u g h t he c o n c e p t o f c or por a t e soci al

r es pons i bi l i t y ma y f r om t i me t o t i me b e

s u p p l a n t e d b y var i ous ot he r f oc us e s s uc h

as soci al r e s pons i ve ne s s , soci al pe r f or ma nc e ,

publ i c pol i cy, et hi cs, or s t a ke hol de r ma n a g e me n t ,

a n unde r l yi ng c ha l l e nge f or all is t o def i ne t he

ki nds o f r esponsi bi l i t i es ma n a g e me n t a n d busi -

nes s es ha ve t o t he c ons t i t ue nc y g r o u p s wi t h

wh i c h t h e y t r ans act a n d i nt er act mo s t f r equent l y.

The p y r a mi d o f c or por a t e soci al r es pons i bi l i t y

gi ves us a f r a me wo r k f or u n d e r s t a n d i n g t he

e vol vi ng nat ur e o f t he f i r m' s e c onomi c , legal,

et hi cal , a n d phi l a nt hr opi c pe r f or ma nc e . The

i mpl e me nt a t i on o f t hes e r esponsi bi l i t i es ma y va r y

d e p e n d i n g u p o n t he f i r m' s size, ma n a g e me n t ' s

Fi gure 6

Three Moral Types and Ori ent at i on Toward

St akehol der Groups: Cust omers and Local Conl muni t y

Type of 3ganageme, Tt Orientation Toward Customer Stakeholders

Immoral Management Customers are vi ewed as opportunities to be exploited for personal or

organizational gain. Ethical standards in dealings do not prevail; indeed, an

active intent to cheat, deceive, and/ or mislead is present. In all marketing

decisions--advertising, pricing, packaging, di st ri but i on--cust omer is taken

advantage of to the fullest extent.

Amoral Management Management does not think t hrough the ethical consequences of its deci-

sions and actions. It simply makes decisions with profitability within the

letter of the law as a guide. Management is not focused on what is fair

from perspective of customer. Focus is on management ' s rights. No consid-

eration is given to ethical implications of interactions with customers.

Moral Management Customer is vmwed as equal partner in transaction. Customer brings needs/

expectations to the exchange transaction and is treated fairly. Managerial

focus is on giving cust omer fair value, full information, fair guarantee, and

satisfaction. Consumer rights are liberally interpreted and honored.

Type of Management

Immoral Management

Amoral Management

Moral Management

Orientation Toward Zocal Community Stakeholders

Exploits communi t y to fullest extent; pollutes the environment. Plant or

business closings take fullest advantage of community. Actively disregards

communi t y needs. Takes fullest advantage of communi t y resources wi t hout

giving anything in return. Violates zoni ng and other ordinances whenever it

can for its own advantage.

Does not take commumt y or its resources into account in management

decision making. Communi t y factors are assumed to be irrelevant to busi-

ness decisions. Community, like employees, is a factor of production. Legal

considerations are followed, but not hi ng more. Deals minimally with com-

munity, its people, communi t y activity, local government.

Sees vital communi t y as a goal to be actively pursued. Seeks to be a lead-

ing citizen and to motivate others to do likewise. Gets actively involved

and helps institutions that need hel p- - school s, recreational groups, philan-

thropic groups. Leadership position in environment, education, culture/arts,

volunteerism, and general communi t y affairs. Firm engages in strategic

philanthropy. Management sees communi t y goals and company goals as

mutually interdependent.

The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responslblh W 47

phi l osophy, cor por at e strategy, i ndust ry charac-

teristics, t he state of t he economy, and ot her such

mi t i gat i ng condi t i ons, but t he f our c ompone nt

part s pr ovi de ma na ge me nt wi t h a skel et al out l i ne

of t he nat ur e and ki nds of t hei r CSR. In frank,

act i on- or i ent ed t erms, busi ness is cal l ed u p o n to:

be profi t abl e, o b e y t he law, be ethical, and be a

good cor por at e citizen.

The st akehol der ma na ge me nt per s pect i ve

pr ovi des not onl y a l anguage and wa y t o per son-

alize rel at i onshi ps wi t h names and faces, but al so

s ome useful concept ual and analytical concept s

for di agnosi ng, anal yzi ng, and prioritizing an

or gani zat i on' s rel at i onshi ps and strategies. Effec-

t i ve or gani zat i ons will pr ogr ess be yond st ake-

hol der i dent i fi cat i on and quest i on what oppor t u-

nities and t hreat s are pos e d by st akehol ders;

what economi c, legal, ethical, and phi l ant hr opi c

responsi bi l i t i es t hey have; and what strategies,

act i ons or deci si ons shoul d be pur s ued to mos t

effect i vel y addr ess t hese responsibilities. The

st akehol der / r esponsi bi l i t y mat ri x pr ovi des a t em-

pl at e ma na ge me nt mi ght use to organi ze its

anal ysi s and deci si on maki ng.

Thr oughout t he article we have be e n bui l d-

ing t owar d t he not i on of an i mpr oved ethical

organi zat i onal cl i mat e as mani f est ed by mor al

management . Moral ma na ge me nt was def i ned

and descr i bed t hr ough a cont rast wi t h i mmor al

and amor al management . Because t he busi ness

l ands cape is r epl et e wi t h i mmor al and amor al

manager s, mor al manager s ma y s omet i mes be

har d to find. Regardless, t hei r charact eri st i cs have

be e n i dent i fi ed and, mos t i mpor t ant , t hei r per-

spect i ve or or i ent at i on t owar ds t he maj or st ake-

hol der gr oups has b e e n profiled. Thes e st ake-

hol der or i ent at i on profi l es gi ve manager s a con-

cept ual but pract i cal t ouchs t one for sort i ng out

t he di fferent cat egor i es or t ypes of ethical ( or

not -so-et hi cal ) behavi or t hat ma y be f ound in

busi ness and ot her organi zat i ons.

It has of t en be e n sai d t hat l eader shi p by ex-

ampl e is t he mos t effect i ve wa y t o i mpr ove busi -

ness ethics. If t hat is true, mor al ma na ge me nt

pr ovi des a model l eader shi p per spect i ve or ori en-

t at i on t hat manager s ma y wi sh to emul at e. One

great fear is t hat manager s ma y t hi nk t hey are

pr ovi di ng ethical l eader shi p just by rej ect i ng i m-

mor al management . However , amor al manage-

ment , part i cul arl y t he uni nt ent i onal variety, ma y

unconsci ousl y prevai l if manager s are not awar e

of what it is and of its dangers. At best , amor al i t y

r epr esent s ethical neutrality, and this not i on is

not t enabl e in t he soci et y of t he 1990s. The st an-

dar d mus t be set high, and mor al ma na ge me nt

pr ovi des t he best e xe mpl a r of what t hat lofty

st andar d mi ght embr ace. Further, mor al manage-

ment , to be fully appr eci at ed, needs t o be s een

wi t hi n t he cont ext of or gani zat i on- st akehol der

rel at i onshi ps. It is t owar d this si ngul ar goal t hat

our ent i re di scussi on has focused. If t he "good

socieW" is to b e c o me a realization, such a hi gh

expect at i on onl y nat ural l y be c ome s t he aspi r at i on

and pr eoccupat i on of management .

R e f e r e n c e s

R.W. Ackerman and R.A. Bauer, Corporate Social Re-

sponsiveness (Reston, Va.: Reston Publishing Co, 1976).

A B. Carroll, "A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model

of Corporate Social Performance," Academy of Man-

agementRevieu,, 4, 4 (1979): 497-505.

A.B. Carroll. "In Search of the Moral Manager," Busi-

ness Horizons, March-April 1987, pp. 7-15.

Committee for Economic Development, Social Respon-

sibilities of Business Corporations (New York: CED,

1971).

K. Davis, "Can Business Afford to Ignore its Social

Responsibilities?" California Management Review, 2, 3

(1960): 70-76.

R. Eetls and C. Walton, Conceptual Foundations of

Business (Homewood, II1.: Richard D. Irwin, 1961).

"Good Timing, Charlie," Forbes, November 27, 1989,

pp. 140-144.

W.C. Frederick, "From CSRx to CSR2: The Maturing of

Business and Society Thought," University of Pittsburgh

Working Paper No. 279, 1978.

M. Friedman, "The Social Responsibility of Business Is

to Increase its Profits," New York Times, September 13,

1970, pp. 122-126.

S.P Sethi, "Dimensions of Corporate Social Responsi-

bility," California Management Review, 1 7, 3 (1975):

58-64.

A r c h i e B. C a r r o l l is R o b e r t W. S c h e r e r

Pr of essor of Ma n a g e me n t a n d Cor po-

r at e Publ i c Affairs at t he C o l l e g e o f Busi-

ness Admi ni st r at i on, University of Geor -

gi a, At hens.

48 Business Horizons / July-August 1991

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- CSR Corporate Social Responsibility A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionVon EverandCSR Corporate Social Responsibility A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our European Future: Charting a Progressive Course in the WorldVon EverandOur European Future: Charting a Progressive Course in the WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Can Business Save the Earth?: Innovating Our Way to SustainabilityVon EverandCan Business Save the Earth?: Innovating Our Way to SustainabilityNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Regulation and Policy of Latin American Energy TransitionsVon EverandThe Regulation and Policy of Latin American Energy TransitionsLucas Noura GuimarãesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainable Investments: A Brief Overview Of Esg Funds In BrasilVon EverandSustainable Investments: A Brief Overview Of Esg Funds In BrasilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change for Forest Policy-Makers: An Approach for Integrating Climate Change Into National Forest Policy in Support of Sustainable Forest Management – Version 2.Von EverandClimate Change for Forest Policy-Makers: An Approach for Integrating Climate Change Into National Forest Policy in Support of Sustainable Forest Management – Version 2.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Energy Unlimited: Four Steps to 100% Renewable EnergyVon EverandEnergy Unlimited: Four Steps to 100% Renewable EnergyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Radical innovation and Open innovation: Creating new growth opportunities for business: Illumination with a case study in the LED industryVon EverandRadical innovation and Open innovation: Creating new growth opportunities for business: Illumination with a case study in the LED industryNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Triple Bottom Line: How Today's Best-Run Companies Are Achieving Economic, Social and Environmental Success - and How You Can TooVon EverandThe Triple Bottom Line: How Today's Best-Run Companies Are Achieving Economic, Social and Environmental Success - and How You Can TooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Improvement Districts: An Introduction to 3 P CitizenshipVon EverandBusiness Improvement Districts: An Introduction to 3 P CitizenshipNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sleeping Giant Awakens: Bio-energy in the UKVon EverandThe Sleeping Giant Awakens: Bio-energy in the UKBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Sustainable Development: Constraints and OpportunitiesVon EverandSustainable Development: Constraints and OpportunitiesBewertung: 1.5 von 5 Sternen1.5/5 (2)

- Predominant Factors for Firms to Reduce Carbon EmissionsVon EverandPredominant Factors for Firms to Reduce Carbon EmissionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asia Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Monitor 2020: Volume II: COVID-19 Impact on Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Developing AsiaVon EverandAsia Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Monitor 2020: Volume II: COVID-19 Impact on Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Developing AsiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Green Growth, Smart Growth: A New Approach to Economics, Innovation and the EnvironmentVon EverandGreen Growth, Smart Growth: A New Approach to Economics, Innovation and the EnvironmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Google Sustainability Report 2015Dokument4 SeitenGoogle Sustainability Report 2015JeffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Us China Cleantech ConnectionDokument12 SeitenUs China Cleantech Connectionamitjain310Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Critique of Competitive AdvantageDokument12 SeitenA Critique of Competitive AdvantagePhilippe HittiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Social ResponsibilityDokument6 SeitenCorporate Social ResponsibilitywhmzahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson No. 13 - Ethics and Social Responsibility in ManagementDokument25 SeitenLesson No. 13 - Ethics and Social Responsibility in Managementjun junNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainability Strategy People and Planet PositiveDokument21 SeitenSustainability Strategy People and Planet PositivetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Review of How CSR Managers Can Inspire Other Leaders To Act On SustainabilityDokument5 SeitenJournal Review of How CSR Managers Can Inspire Other Leaders To Act On Sustainabilitymyra wee100% (1)

- Matthias Haber - Improving Public ProcurementDokument44 SeitenMatthias Haber - Improving Public ProcurementMatt HaberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group Coursework and Project Cover Sheet Department of Civil and Environmental EngineeringDokument15 SeitenGroup Coursework and Project Cover Sheet Department of Civil and Environmental EngineeringMubin Al-ManafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pestle Analysis of A Furniture Industry in South AfricaDokument2 SeitenPestle Analysis of A Furniture Industry in South AfricaEver Assignment0% (1)

- Corporate Social Responsibility CSRDokument25 SeitenCorporate Social Responsibility CSRIoana-Loredana Ţugulea100% (1)

- ETHICSDokument2 SeitenETHICSMai RosaupanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Online CSR Communication by The Philippine Water UtilitiesDokument21 SeitenOnline CSR Communication by The Philippine Water UtilitiesEvan SwandieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Issues in IbDokument14 SeitenEthical Issues in IbAanchal GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calculating The Value of Impact Investing PDFDokument9 SeitenCalculating The Value of Impact Investing PDFPauloNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Resource-Based View of The FirmDokument11 SeitenA Resource-Based View of The Firmxaxif8265Noch keine Bewertungen

- There Chance of Winning The Completion Is 20%.: Assignment # 2Dokument3 SeitenThere Chance of Winning The Completion Is 20%.: Assignment # 2Muhammad Hazim TararNoch keine Bewertungen

- Globalization in The Age of TrumpDokument22 SeitenGlobalization in The Age of TrumpCristin MandonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 3 - CSRDokument18 SeitenGroup 3 - CSRAshima TayalNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSRDokument56 SeitenCSRLou Anthony A. CaliboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study Nike's CSR ChallengeDokument6 SeitenCase Study Nike's CSR ChallengeIke Ace EvbuomwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance - Giorgio TomassettiDokument43 SeitenEntrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance - Giorgio TomassettiGiorgio TomassettiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Porters StrategyDokument14 SeitenPorters StrategyDeepshikha Goel100% (1)

- Case - VEJA - Adaptado PDFDokument8 SeitenCase - VEJA - Adaptado PDFGabriella Sant'AnnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Five Generations of Innovation ModelsDokument5 SeitenFive Generations of Innovation ModelsJavi OlivoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employee Theft 3 (Ethical Theory)Dokument15 SeitenEmployee Theft 3 (Ethical Theory)athirah jamaludinNoch keine Bewertungen

- TitanDokument6 SeitenTitanakhilprasad1Noch keine Bewertungen

- CSR MicrosoftDokument2 SeitenCSR MicrosoftnainaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 9 - Cooperative StrategyDokument24 SeitenModule 9 - Cooperative Strategyian92193Noch keine Bewertungen

- BLOWFIELD Michael - Business and Development - 2012Dokument15 SeitenBLOWFIELD Michael - Business and Development - 2012Sonia DominguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vrio Analysis Pep Coc CPKDokument6 SeitenVrio Analysis Pep Coc CPKnoonot126Noch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Change and ComplexityDokument7 SeitenEnvironmental Change and ComplexityIffah Nadzirah100% (2)

- CRKC7044 Internet of Things Final AssessmentDokument5 SeitenCRKC7044 Internet of Things Final AssessmentK142526 AlishanNoch keine Bewertungen

- PositioningDokument9 SeitenPositioningTyger KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of ESG Screening On Return, Risk, and Diversification PDFDokument11 SeitenThe Impact of ESG Screening On Return, Risk, and Diversification PDFJuan José MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blue Entrepreneur Personalities Business InfographicDokument1 SeiteBlue Entrepreneur Personalities Business InfographiceriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data PD Bank Buku 1 - 3 Bloomberg & GDPDokument51 SeitenData PD Bank Buku 1 - 3 Bloomberg & GDPeriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Hillier (2019)Dokument12 SeitenDavid Hillier (2019)eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appendix 1 - Q2 Progress ReportDokument28 SeitenAppendix 1 - Q2 Progress ReporteriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eri Wirandana - Role of EntrpreneurDokument24 SeitenEri Wirandana - Role of EntrpreneureriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Process Reengineering: CEM 515 For: Dr. Abdulaziz Bubshait By: Hassan Al-BekhitDokument62 SeitenBusiness Process Reengineering: CEM 515 For: Dr. Abdulaziz Bubshait By: Hassan Al-BekhitrishimaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Data & Ratio 2014 - SamplingDokument356 SeitenFinancial Data & Ratio 2014 - SamplingeriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample 3 Proposal Bus With MarketingaDokument8 SeitenSample 3 Proposal Bus With MarketingaeriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Good Corporate Governance (GCG) On Risk Management in Property and Real Estate EmitentDokument18 SeitenImpact of Good Corporate Governance (GCG) On Risk Management in Property and Real Estate EmitenteriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary Control Vs NIMODokument2 SeitenSummary Control Vs NIMOeriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAMPLE 4 PROPOSAL Bus With Logistics QuantsDokument9 SeitenSAMPLE 4 PROPOSAL Bus With Logistics QuantseriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sturges1926 PDFDokument3 SeitenSturges1926 PDFeriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal MR MC AVGDokument1 SeiteSoal MR MC AVGeriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sem 1 - 5Dokument89 SeitenSem 1 - 5eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ringkasan Saham 2008Dokument27 SeitenRingkasan Saham 2008eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baby Shopping AzfarDokument11 SeitenBaby Shopping AzfareriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cox (1992)Dokument34 SeitenCox (1992)eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indonesia Employment Outlook and Salary Guide 2016Dokument36 SeitenIndonesia Employment Outlook and Salary Guide 2016eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporates Ocial Performancer EvisitedDokument29 SeitenCorporates Ocial Performancer Evisitederiwirandana100% (1)

- Executive Summary - Business Plan Heavy EquipmentDokument4 SeitenExecutive Summary - Business Plan Heavy EquipmenteriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ringkasan Saham 2011Dokument30 SeitenRingkasan Saham 2011eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ringkasan Saham 2005Dokument16 SeitenRingkasan Saham 2005eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ringkasan Saham 2010Dokument21 SeitenRingkasan Saham 2010eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ringkasan Saham 2005Dokument16 SeitenRingkasan Saham 2005eriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Value at RiskDokument83 SeitenValue at RiskeriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islam SocietyDokument24 SeitenIslam SocietyeriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mantak Chia - Chi Self MassageDokument122 SeitenMantak Chia - Chi Self Massagetilopa100% (45)

- African EntrepreneurshipDokument320 SeitenAfrican EntrepreneurshiperiwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentasi DiabetesDokument35 SeitenPresentasi DiabeteseriwirandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harmony Scope and Sequence PDFDokument7 SeitenHarmony Scope and Sequence PDFRidwan SumitroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eric Soulsby Assessment Notes PDFDokument143 SeitenEric Soulsby Assessment Notes PDFSaifizi SaidonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 6 - GMRC: L'Altra Montessori School, Inc. Elementary Department Learning PlanDokument2 SeitenGrade 6 - GMRC: L'Altra Montessori School, Inc. Elementary Department Learning PlanBea Valerie GrislerNoch keine Bewertungen

- FA Mathematics (Class IX)Dokument228 SeitenFA Mathematics (Class IX)Partha Sarathi MannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WLP#6 Mathematics10 Sy2019-2020 PampangaDokument4 SeitenWLP#6 Mathematics10 Sy2019-2020 PampangaAnonymous FNahcfNoch keine Bewertungen

- 118-Article Text-202-3-10-20190730Dokument6 Seiten118-Article Text-202-3-10-20190730GraceNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Artist Is PresentDokument10 SeitenThe Artist Is Presentsancho108Noch keine Bewertungen

- PEC Self Rating Questionnaire and Score Computation 2Dokument10 SeitenPEC Self Rating Questionnaire and Score Computation 2kenkoykoy0% (2)

- Tapping Into Ultimate Success SummaryDokument6 SeitenTapping Into Ultimate Success SummaryKeith Leonard67% (3)

- Presentation of ": Jigjiga UniversityDokument26 SeitenPresentation of ": Jigjiga Universityhasan rashidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yanilda Goris - Trauma-Informed Schools Annotated BibliographyDokument7 SeitenYanilda Goris - Trauma-Informed Schools Annotated Bibliographyapi-302627207100% (1)

- Module - Principles of Teaching 2Dokument11 SeitenModule - Principles of Teaching 2noreen agripa78% (9)

- Northern Mindanao Colleges, Inc.: Self-Learning Module For Personal Development Quarter 1, Week 5Dokument8 SeitenNorthern Mindanao Colleges, Inc.: Self-Learning Module For Personal Development Quarter 1, Week 5Yara King-PhrNoch keine Bewertungen

- 25 Key Slave RulesDokument2 Seiten25 Key Slave RulesBritny Smith50% (2)

- Mapeh 9 Tos 1ST QuarterDokument5 SeitenMapeh 9 Tos 1ST QuarterKrizha Kate MontausNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samra Shehzadi, Peace Psy, Assignment 1Dokument12 SeitenSamra Shehzadi, Peace Psy, Assignment 1Fatima MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Detailed Narrative Report of What Has Been Transpired From The Start and End of ClassDokument4 SeitenDetailed Narrative Report of What Has Been Transpired From The Start and End of ClassMaribel LimsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handout - Theories of ManagementDokument7 SeitenHandout - Theories of ManagementStephanie DecidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Career Guidance 1Dokument14 SeitenCareer Guidance 1leo sentelicesNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIDTERM-Features of Human Language by HockettDokument4 SeitenMIDTERM-Features of Human Language by HockettBaucas, Rolanda D.100% (1)

- 12.illusions of FamiliarityDokument19 Seiten12.illusions of FamiliarityBlayel FelihtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan Colour WheelDokument3 SeitenLesson Plan Colour WheelFatimah WasimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1.1 Intro PsyDokument27 SeitenChapter 1.1 Intro PsyFatimah EarhartNoch keine Bewertungen

- Autonomous Learning Natalie Castillo Z Institución Universitaria Colombo AmericanaDokument8 SeitenAutonomous Learning Natalie Castillo Z Institución Universitaria Colombo AmericanalauritamorosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Home-School Link: My Learning EssentialsDokument11 SeitenHome-School Link: My Learning EssentialsCV ESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Decision MakingDokument16 SeitenStrategic Decision MakingAnkit SinglaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenLesson Planapi-501298764Noch keine Bewertungen

- Construct ValidityDokument10 SeitenConstruct ValidityAnasNoch keine Bewertungen

- The 7 Pickup Artist SecretsDokument30 SeitenThe 7 Pickup Artist Secretsizemaster100% (1)

- How To Write An EssayDokument2 SeitenHow To Write An Essayjavokhetfield5728Noch keine Bewertungen