Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Hiper in Pregnant PDF

Hochgeladen von

Erba Epril RiadiOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hiper in Pregnant PDF

Hochgeladen von

Erba Epril RiadiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

clinical practice

The new engl and journal o f medicine

n engl j med 365;5 nejm.org august 4, 2011

439

This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem.

Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines,

when they exist. The article ends with the authors clinical recommendations.

An audio version

of this article

is available at

NEJM.org

Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy

Ellen W. Seely, M.D., and Jeffrey Ecker, M.D.

From the Endocrinology, Diabetes, and

Hypertension Division, Brigham and

Womens Hospital (E.W.S.); Harvard

Medical School (E.W.S., J.E.); and the

MaternalFetal Medicine Division, Mas-

sachusetts General Hospital (J.E.) all

in Boston. Address reprint requests to

Dr. Seely at the Division of Endocrinolo-

gy, Diabetes, and Hypertension, Brigham

and Womens Hospital, 221 Longwood

Ave., Boston, MA 02115, or at eseely@

partners.org.

This article (10.1056/NEJMcp0804872) was

updated on October 26, 2011, at NEJM

.org.

N Engl J Med 2011;365:439-46.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society.

A 35-year-old woman who has never been pregnant and who has a 5-year history of hy-

pertension wants to become pregnant. She has stopped using contraception. Her only

medication is lisinopril at a dose of 10 mg per day. Her blood pressure is 124/68 mm Hg,

and her body-mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height

in meters) is 27. What would you advise?

The Clinical Problem

Chronic hypertension in pregnancy is defined as a blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg

systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic pressure before pregnancy or, for women who first

present for care during pregnancy, before 20 weeks of gestation. The prevalence of

chronic hypertension in pregnancy in the United States is estimated to be as high

as 3%

1

and has been increasing over time. This increase in prevalence is primarily

attributable to the increased prevalence of obesity, a major risk factor for hypertension,

as well as the delay in childbearing to ages when chronic hypertension is more com-

mon. Therefore, an increasing number of women enter pregnancy with hypertension

and need both counseling regarding the risks of chronic hypertension in pregnancy

and adjustment of antihypertensive treatment before and during pregnancy.

Most women with chronic hypertension have good pregnancy outcomes, but these

women are at increased risk for pregnancy complications, as compared with the

general population. The risk of an adverse outcome increases with the severity of

hypertension and end-organ damage.

2

Furthermore, some antihypertensive agents

carry risks in pregnancy and should be discontinued before conception.

3

Since

nearly 50% of pregnancies in the United States are unplanned,

4

it is important to

counsel women of reproductive age who have hypertension regarding such risks

as part of routine care.

Women with chronic hypertension have an increased frequency of preeclampsia

(17 to 25%,

1,5,6

vs. 3 to 5% in the general population), as well as placental abruption,

fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and cesarean section. The risk of superimposed

preeclampsia increases with an increasing duration of hypertension.

2

Preeclampsia

is a leading cause of preterm birth and cesarean delivery in this population.

6,7

In a

study involving 861 women with chronic hypertension, preeclampsia developed in

22%, and the condition occurred in nearly half these women at less than 34 weeks of

gestation, earlier than is typical in women without antecedent hypertension. Women

with chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia are at increased risk for

giving birth to an infant who is small for gestational age

6

and for placental abrup-

tion, as compared with women with chronic hypertension without superimposed

preeclampsia.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by erba epril on October 6, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The new engl and journal o f medicine

n engl j med 365;5 nejm.org august 4, 2011

440

Even in the absence of superimposed preeclamp-

sia, women with chronic hypertension have an in-

creased risk of adverse outcomes.

5

Studies that were

performed in Canada, the United States, and New

Zealand have indicated that fetal growth restric-

tion (estimated or actual fetal weight, <10th percen-

tile for population norms) complicates 10 to 20%

of such pregnancies.

1,5,6

In an analysis of the Dan-

ish National Birth Cohort, after adjustment for

age, body-mass index, smoking status, parity,

and diabetes, chronic hypertension was associ-

ated with approximately five times the risk of

preterm birth and a 50% increase in the risk of

giving birth to an infant who is small for gesta-

tional age.

8

Women with chronic hypertension have

more than twice the frequency of placental ab-

ruption as normotensive women (1.56% vs. 0.58%),

9

a risk that is further increased in women with

preeclampsia.

2,9

Chronic hypertension has also

been associated with an increased risk of still-

birth.

10

Most women with chronic hypertension have

a decrease in blood pressure during pregnancy,

similar to that observed in normotensive women;

blood pressure falls toward the end of the first

trimester and rises toward prepregnancy values

during the third trimester.

5,11,12

As a result, anti-

hypertensive medications can often be tapered dur-

ing pregnancy. However, in addition to the subset

of women with chronic hypertension in whom

preeclampsia develops, another 7 to 20% of women

have worsening of hypertension during pregnancy

without the development of preeclampsia.

13

Strategies and Evidence

Prepregnancy Evaluation

The care of women with chronic hypertension

should begin before pregnancy in order to opti-

mize treatment regimens before conception and

facilitate counseling concerning potential preg-

nancy complications. Prepregnancy evaluation of

chronic hypertension should generally follow the

guidelines of the Joint National Committee on

Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment

of High Blood Pressure 7 (JNC 7) for assessment of

target-organ damage, recommendations that do

not include specific modifications for evaluation

during pregnancy.

14

Such recommendations in-

clude the use of electrocardiography and assess-

ment of blood glucose, hematocrit, serum potas-

sium, creatinine, calcium, and lipoprotein profile,

as well as urinalysis. Given the increased risk of

preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension,

evaluation before pregnancy should also include

a 24-hour quantification of urine protein to facili-

tate the identification of subsequent superimposed

preeclampsia. The presence of end-organ manifes-

tations of hypertension may worsen the prognosis

during pregnancy and should be taken into account

in counseling. For example, the presence of pro-

teinuria at baseline increases the risks of super-

imposed preeclampsia and growth restriction.

2

In most women with chronic hypertension, the

cause of the disorder is unknown. The rate of iden-

tifiable causes of hypertension in women of child-

bearing age is not well studied. The evaluation

of identifiable causes of hypertension is generally

limited to women with hypertension that is resis-

tant to therapy or that requires multiple medica-

tions or to those who have symptoms or signs

that suggest a secondary cause; evaluations in such

cases should follow the JNC 7 guidelines.

14

How-

ever, because testing in these cases may require

the diagnostic use of radiation and because the

treatment of detected abnormalities often includes

surgery, practitioners should pursue such evalu-

ations before conception whenever possible.

Monitoring for Preeclampsia

Identifying superimposed preeclampsia in women

with chronic hypertension can be challenging, giv-

en that blood pressures are high to start and some

women may have baseline proteinuria. Superim-

posed preeclampsia should always be considered

when the blood pressure increases in pregnancy

or when there is a new onset of or an increase in

baseline proteinuria. An elevated uric acid level

may help to distinguish the two conditions, al-

though there is substantial overlap in levels. The

presence of thrombocytopenia or elevated values

on liver-function testing may also support a diag-

nosis of preeclampsia. Recently, serum and urinary

angiogenic markers have been studied as possible

aids in the diagnosis of superimposed preeclamp-

sia,

15

but data are currently insufficient to support

their use in this population.

Treatment Options

Antihypertensive Medications

A primary reason for treating hypertension in preg-

nancy is to reduce maternal morbidity associated

with severe hypertension (Table 1). A meta-analysis

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by erba epril on October 6, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

clinical practice

n engl j med 365;5 nejm.org august 4, 2011

441

including 28 randomized trials comparing anti-

hypertensive treatment either with placebo or with

no treatment showed that antihypertensive treat-

ment significantly reduced the risk of severe hyper-

tension. However, treatment did not reduce the

risks of superimposed preeclampsia, placental ab-

ruption, or growth restriction, nor did it improve

neonatal outcomes.

13

The antihypertensive agent with the largest

quantity of data regarding fetal safety is methyl-

dopa, which has been used during pregnancy since

the 1960s. In one study,

16

no adverse developmen-

tal outcomes were reported during 7.5 years of

follow-up among 195 children whose mothers had

received methyldopa. Thus, methyldopa is consid-

ered to be a first-line therapy in pregnancy by

many guideline groups.

17-19

However, methyldopa

frequently causes somnolence, which may limit its

tolerability and necessitate the use of other agents.

In a meta-analysis of randomized trials compar-

ing different antihypertensive agents in pregnancy,

the use of beta-blockers resulted in fewer episodes

of severe hypertension than the use of methyldo-

pa.

13

Labetalol, a combined alpha- and beta-recep-

tor blocker, is often recommended as another first-

line

18

or second-line

17

therapy for hypertension in

pregnancy. Although some data have suggested an

association between atenolol and fetal growth re-

striction,

20

this finding has not been reported with

the use of other beta-blockers or labetalol, and

whether the observed association was attribut-

able to the use of atenolol or to the underlying

hypertension is uncertain. Nonetheless, some ex-

perts consider it prudent to avoid the use of ateno-

lol during pregnancy.

18

Long-acting calcium-channel blockers also ap-

pear to be safe in pregnancy, although experience

is more limited than with labetalol.

21

Diuretics

were long considered contraindicated in pregnancy

because of concern about volume depletion. How-

ever, a review of nine randomized trials showed

no significant difference in pregnancy outcomes

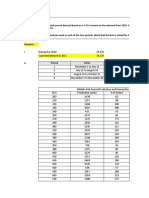

Table 1. Common Pharmacologic Therapies for Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy.*

Drug

Class or Mechanism

of Action Usual Range of Dose Comments

Methyldopa Centrally acting alpha

agonist

250 mg to 1.5 g orally twice

daily

Often used as first-line therapy

Long-term data suggest safety

in offspring

Labetalol Combined alpha- and

beta-blocker

1001200 mg orally twice daily Often used as first-line therapy

May exacerbate asthma

Intravenous formulation is

available to treat hyper -

tensive emergencies

Metoprolol Beta-blocker 25200 mg orally twice daily May exacerbate asthma

Possible association with fetal

growth restriction

Other beta-blockers (e.g., pindo-

lol and propranolol) have

been safely used

Some experts recommend avoid-

ing atenolol

Nifedipine (long-

acting)

Calcium-channel

blocker

30120 mg orally once daily Use of short-acting nifedipine

is typically not recommend-

ed, given risk of hypotension

Other calcium-channel blockers

have been safely used

Hydralazine Peripheral vasodilator 50300 mg orally in two or four

divided doses

Intravenous formulation is avail-

able to treat hypertensive

emergencies

Hydrochlorothiazide Diuretic 12.550 mg orally once daily Previous concerns about in-

creased risk of an adverse

outcome are not supported

by recent data

* The use of angiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers is contraindicated in pregnancy

because of the risk of birth defects and fetal or neonatal renal failure.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by erba epril on October 6, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The new engl and journal o f medicine

n engl j med 365;5 nejm.org august 4, 2011

442

among women with hypertension who took diuret-

ics and those who took no antihypertensive medi-

cation.

22

Accordingly, some guidelines support the

continuation of diuretic therapy during pregnancy

in women with chronic hypertension who were

previously treated with these agents.

17,18

Angiotensin-convertingenzyme (ACE) inhib-

itors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) are

contraindicated in pregnancy. Their use in the sec-

ond half of pregnancy has been associated with

oligohydramnios (probably resulting from impaired

fetal renal function) and neonatal anuria, growth

abnormalities, skull hypoplasia, and fetal death.

23-26

ACE inhibitors have also been associated with po-

tential teratogenic effects. In a retrospective cohort

study that included women who had been exposed

to ACE inhibitors in the first trimester, the risk

ratio associated with exposure to ACE inhibitors,

as compared with exposure to other antihyper-

tensive agents, was 4.0 (95% confidence interval

[CI], 1.9 to 7.3) for cardiovascular defects and 5.5

(95% CI, 1.7 to 17.6) for central-nervous-system

defects.

3

Although the observational nature of the

study makes it impossible to rule out confound-

ing by other factors associated with the use of ACE

inhibitors, it is recommended that women taking

ACE inhibitors and, by extrapolation, other block-

ers of the reninangiotensin system (e.g., ARBs and

renin inhibitors) be switched to another antihyper-

tensive class of drugs before conception whenever

possible.

Lifestyle modifications, including weight re-

duction and increased physical activity, have been

shown to improve blood-pressure control in per-

sons who are not pregnant. In addition, an in-

creased body-mass index is a well-established risk

factor for preeclampsia.

27

The American College

of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends weight

reduction before pregnancy in obese women.

28

However, data are lacking to inform whether such

measures improve pregnancy outcomes specifi-

cally in women with hypertension.

Blood-Pressure Goals in Pregnancy

In the absence of conclusive data from randomized

trials to guide thresholds for initiating the use

of antihypertensive medications or blood-pressure

targets in pregnancy, various professional guide-

lines provide disparate recommendations regard-

ing indications for starting therapy (ranging from

a blood pressure of >159/89 mm Hg

14,17,29

to one

of >169/109 mm Hg

18,19

) and for blood-pressure

targets for women who are receiving therapy (rang-

ing from <140/90 mm Hg

29

to <160/110 mm Hg

14

).

Some experts recommend stopping antihyperten-

sive agents during pregnancy, as long as blood pres-

sures fall below such thresholds. For women whose

antihypertensive therapy is continued, aggressive

lowering of blood pressure should be avoided. A

meta-analysis of randomized trials of antihyperten-

sive treatment of mild-to-moderate hypertension in

pregnancy (both chronic and pregnancy-associated)

suggested that a greater magnitude of blood pres-

sure lowering was associated with an increased

risk of fetal growth restriction.

30

Accordingly, pre-

pregnancy doses of antihypertensive agents may

need to be reduced, particularly in the second tri-

mester, when blood pressures typically fall with

respect to levels before pregnancy or during the

first trimester.

Prevention of Preeclampsia

Since superimposed preeclampsia is the major ad-

verse pregnancy outcome associated with chronic

hypertension, many women ask whether any ther-

apies can decrease this risk. Large, randomized,

placebo-controlled trials have shown no signifi-

cant reduction in the risk of preeclampsia associ-

ated with the use of low-dose aspirin,

31

calcium

supplementation,

32

or antioxidant supplementa-

tion with vitamins C and E,

33

although meta-

analyses of smaller studies suggested benefit.

34,35

Fetal Surveillance

Efforts to monitor women and their fetuses for

complications may include more frequent prena-

tal visits for women with chronic hypertension

than for women without this condition. Such vis-

its are intended to monitor women closely for com-

plications of chronic hypertension by measuring

blood pressure and urine protein. Because such

pregnancies have an increased likelihood of fetal

growth restriction, the evaluation of fetal growth

is recommended. Many obstetricians supplement

regular evaluation of fundal height with ultraso-

nographic estimation of fetal weight, beginning

in the early third trimester and continuing at in-

tervals of 2 to 4 weeks, depending on maternal

blood pressure, medications, complications, and

findings on previous imaging. Although data from

low-risk populations suggest that ultrasonography

and evaluation of fundal height have shown sim-

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by erba epril on October 6, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

clinical practice

n engl j med 365;5 nejm.org august 4, 2011

443

ilar results for the detection of growth restriction,

36

ultrasonography also assesses amniotic-fluid vol-

ume and fetal movements and tone (biophysical

profile), evaluations that may be useful with re-

spect to the risks associated with chronic hyper-

tension in pregnancy.

Given the increased risk of stillbirth in mothers

with hypertension,

10

surveillance of fetal well-

being is also recommended by some experts, al-

though others recommend restricting such testing

to pregnancies with complications, such as growth

restriction or preeclampsia.

17,18

Testing may also

include the evaluation of the pattern and variabil-

ity of the fetal heart rate (nonstress testing). Ma-

ternal complications (e.g., preeclampsia or wors-

ening hypertension), nonreassuring fetal-testing

results, or concern about fetal growth restriction

are often indications for early delivery. Clinicians

must weigh the risks of fetal morbidity associated

with delivery before term against the risks of ma-

ternal and fetal complications from continued ex-

pectant management. In women with chronic

hypertension without additional complications,

delivery is often planned near the estimated due

date, although the need for such intervention is

uncertain if testing results are reassuring and fetal

growth is normal.

Breast-feeding

Breast-feeding should be encouraged in women

with chronic hypertension, including those requir-

ing medication. Although most antihypertensive

agents can be detected in breast milk, levels are

generally lower than those in maternal plasma.

37

These relatively low levels and observational data

from series of women who were receiving medi-

cations while breast-feeding have led the American

Academy of Pediatrics to label most antihyperten-

sive agents, including ACE inhibitors, as usually

compatible with breast-feeding.

38

Since case re-

ports have described lethargy and bradycardia in

newborns who are breast-fed by mothers taking

atenolol, the American Academy of Pediatrics rec-

ommends that atenolol be used with caution. No

such cautions are noted for other beta-blockers,

such as metoprolol. Because data are lacking with

respect to the use of ARBs and breast-feeding, it is

recommended that other agents be considered for

treating hypertension in lactating women. Recom-

mendations from the Society of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists of Canada note that the use of

long-acting nifedipine, labetalol, methyldopa, cap-

topril, and enalapril is acceptable during breast-

feeding.

21

Areas of Uncertainty

Data from randomized trials to inform the treat-

ment of women with chronic hypertension in preg-

nancy are limited, including whether women with

mild-to-moderate hypertension should receive anti-

hypertensive treatment, which target blood pres-

sure should be used for treatment, and which

antihypertensive agents are superior for use in

pregnancy. The Control of Hypertension in Preg-

nancy Study (CHIPS; ClinicalTrials.gov number,

NCT01192412) is an ongoing randomized trial in-

volving women with chronic hypertension or preg-

nancy-associated hypertension that is comparing

less tight control (target diastolic blood pressure,

100 mm Hg) with tight control (target diastolic

blood pressure, 85 mm Hg) with respect to mater-

nal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes

39

; study comple-

tion is anticipated in 2013. Additional prospective

studies are needed to assess maternal and fetal

outcomes associated with the use of different anti-

hypertensive therapies and blood-pressure targets.

Long-term follow-up of both mother and offspring

is also warranted, particularly given the increas-

ing evidence that the environment in utero influ-

ences later health outcomes.

40

Guidelines

Guidelines for the management of pregnancy in

women with chronic hypertension have been pub-

lished by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists,

18

the Society of Obstetricians

and Gynaecologists of Canada,

41

the Working Group

of the National High Blood Pressure Education

Program,

17

and the Australasian Society for the

Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy

29

(Table 2).

These guidelines all emphasize the importance

of preconception planning and management, rec-

ommend that ACE inhibitors be avoided in preg-

nancy, and emphasize the long experience support-

ing the safety of methyldopa during pregnancy.

However, different guidelines suggest disparate

thresholds for antihypertensive treatment and dif-

fer in recommendations regarding certain medi-

cations, including whether they endorse the use

of atenolol in pregnancy.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by erba epril on October 6, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The new engl and journal o f medicine

n engl j med 365;5 nejm.org august 4, 2011

444

T

a

b

l

e

2

.

G

u

i

d

e

l

i

n

e

s

f

o

r

A

n

t

i

h

y

p

e

r

t

e

n

s

i

v

e

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

f

o

r

C

h

r

o

n

i

c

H

y

p

e

r

t

e

n

s

i

o

n

i

n

P

r

e

g

n

a

n

c

y

.

*

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

A

C

O

G

1

8

(

2

0

0

1

)

N

H

B

P

E

P

W

o

r

k

i

n

g

G

r

o

u

p

1

7

(

2

0

0

0

)

J

N

C

7

1

4

(

2

0

0

3

)

C

a

n

a

d

i

a

n

4

1

(

2

0

0

8

)

A

u

s

t

r

a

l

a

s

i

a

n

2

9

(

2

0

0

0

)

E

v

a

l

u

a

t

i

o

n

b

e

f

o

r

e

p

r

e

g

n

a

n

c

y

C

o

n

s

i

d

e

r

t

e

s

t

i

n

g

o

f

c

r

e

a

t

i

n

i

n

e

,

b

l

o

o

d

u

r

e

a

n

i

t

r

o

g

e

n

,

2

4

-

h

r

u

r

i

n

e

p

r

o

t

e

i

n

a

n

d

c

r

e

-

a

t

i

n

i

n

e

c

l

e

a

r

a

n

c

e

,

u

r

i

c

a

c

i

d

,

a

l

o

n

g

w

i

t

h

e

l

e

c

t

r

o

-

c

a

r

d

i

o

g

r

a

p

h

y

,

e

c

h

o

c

a

r

-

d

i

o

g

r

a

p

h

y

,

o

p

h

t

h

a

l

m

o

-

l

o

g

i

c

e

x

a

m

i

n

a

t

i

o

n

,

a

n

d

r

e

n

a

l

u

l

t

r

a

s

o

n

o

g

r

a

p

h

y

E

v

a

l

u

a

t

e

f

o

r

s

e

c

o

n

d

a

r

y

c

a

u

s

e

s

i

n

p

r

e

s

e

n

c

e

o

f

s

u

g

g

e

s

t

i

v

e

s

y

m

p

t

o

m

s

o

r

s

i

g

n

s

I

n

w

o

m

e

n

w

i

t

h

a

h

i

s

t

o

r

y

o

f

h

y

p

e

r

t

e

n

s

i

o

n

f

o

r

s

e

v

e

r

a

l

y

e

a

r

s

,

e

v

a

l

u

a

t

e

f

o

r

t

a

r

g

e

t

-

o

r

g

a

n

d

a

m

a

g

e

,

i

n

c

l

u

d

i

n

g

l

e

f

t

v

e

n

t

r

i

c

u

l

a

r

h

y

p

e

r

t

r

o

-

p

h

y

,

r

e

t

i

n

o

p

a

t

h

y

,

a

n

d

r

e

n

a

l

d

i

s

e

a

s

e

A

s

s

e

s

s

f

o

r

s

e

c

o

n

d

a

r

y

c

a

u

s

e

s

a

n

d

p

r

e

s

e

n

c

e

o

f

t

a

r

g

e

t

-

o

r

g

a

n

d

a

m

a

g

e

N

o

t

s

p

e

c

i

f

i

e

d

I

n

v

e

s

t

i

g

a

t

e

p

o

t

e

n

t

i

a

l

c

a

u

s

e

s

o

f

s

e

c

o

n

d

a

r

y

h

y

p

e

r

t

e

n

-

s

i

o

n

I

f

u

r

i

n

a

l

y

s

i

s

i

s

p

o

s

i

t

i

v

e

f

o

r

p

r

o

t

e

i

n

,

t

h

e

n

2

4

-

h

r

u

r

i

n

e

p

r

o

t

e

i

n

a

n

a

l

y

s

i

s

o

r

m

e

a

-

s

u

r

e

m

e

n

t

o

f

s

p

o

t

u

r

i

n

e

p

r

o

t

e

i

n

-

t

o

-

c

r

e

a

t

i

n

i

n

e

r

a

-

t

i

o

;

t

e

s

t

i

n

g

o

f

b

l

o

o

d

g

l

u

-

c

o

s

e

,

e

l

e

c

t

r

o

l

y

t

e

s

,

a

n

d

r

e

n

a

l

f

u

n

c

t

i

o

n

(

e

.

g

.

,

s

e

-

r

u

m

c

r

e

a

t

i

n

i

n

e

a

n

d

u

r

i

c

a

c

i

d

)

B

l

o

o

d

-

p

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

l

e

v

e

l

s

f

o

r

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

a

n

d

g

o

a

l

s

T

r

e

a

t

i

f

b

l

o

o

d

p

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

i

s

1

8

0

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

i

c

o

r

1

1

0

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

f

o

r

m

a

t

e

r

n

a

l

b

e

n

e

f

i

t

M

i

l

d

h

y

p

e

r

t

e

n

s

i

o

n

(

1

4

0

1

7

9

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

i

c

o

r

9

0

1

0

9

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

)

u

s

u

a

l

l

y

d

o

e

s

n

o

t

r

e

q

u

i

r

e

p

h

a

r

m

a

c

o

l

o

g

i

c

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

I

f

m

e

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

i

s

t

a

p

e

r

e

d

,

r

e

-

s

t

a

r

t

i

f

>

1

5

0

1

6

0

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

i

c

o

r

>

1

0

0

1

1

0

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

C

o

n

s

i

d

e

r

t

a

p

e

r

i

n

g

a

n

t

i

h

y

p

e

r

-

t

e

n

s

i

v

e

m

e

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

a

n

d

r

e

i

n

s

t

i

t

u

t

e

o

r

i

n

c

r

e

a

s

e

d

o

s

e

i

f

b

l

o

o

d

p

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

i

s

>

1

5

0

1

6

0

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

-

i

c

o

r

>

1

0

0

1

1

0

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

C

o

n

t

i

n

u

e

m

e

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

i

f

t

h

e

r

e

i

s

t

a

r

g

e

t

-

o

r

g

a

n

d

a

m

a

g

e

o

r

a

p

r

e

v

i

o

u

s

r

e

q

u

i

r

e

m

e

n

t

f

o

r

m

u

l

t

i

p

l

e

a

n

t

i

h

y

p

e

r

t

e

n

-

s

i

v

e

a

g

e

n

t

s

f

o

r

b

l

o

o

d

-

p

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

I

f

m

e

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

i

s

s

t

o

p

p

e

d

,

r

e

-

i

n

s

t

i

t

u

t

e

i

f

b

l

o

o

d

p

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

i

s

1

5

0

1

6

0

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

-

t

o

l

i

c

o

r

1

0

0

1

1

0

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

T

r

e

a

t

i

f

b

l

o

o

d

p

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

i

s

>

1

5

9

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

i

c

o

r

>

1

0

9

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

t

o

l

o

w

e

r

m

a

t

e

r

n

a

l

r

i

s

k

S

u

g

g

e

s

t

e

d

t

a

r

g

e

t

<

1

5

6

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

i

c

a

n

d

<

1

0

6

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

,

b

u

t

i

n

p

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

w

i

t

h

m

a

j

o

r

c

a

r

d

i

o

v

a

s

c

u

l

a

r

r

i

s

k

f

a

c

t

o

r

s

,

<

1

4

0

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

i

c

a

n

d

<

9

0

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

T

r

e

a

t

i

f

b

l

o

o

d

p

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

i

s

>

1

7

0

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

i

c

o

r

>

1

1

0

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

S

u

g

g

e

s

t

e

d

t

a

r

g

e

t

i

s

1

2

0

1

4

0

m

m

H

g

s

y

s

t

o

l

i

c

a

n

d

8

0

9

0

m

m

H

g

d

i

a

s

t

o

l

i

c

i

f

t

h

e

r

e

a

r

e

n

o

u

n

d

u

e

s

i

d

e

e

f

f

e

c

t

s

M

e

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

F

i

r

s

t

-

l

i

n

e

,

m

e

t

h

y

l

d

o

p

a

o

r

l

a

b

e

t

a

l

o

l

A

v

o

i

d

A

C

E

i

n

h

i

b

i

t

o

r

s

i

n

s

e

c

-

o

n

d

a

n

d

t

h

i

r

d

t

r

i

m

e

s

t

e

r

s

M

e

t

h

y

l

d

o

p

a

i

s

p

r

e

f

e

r

r

e

d

b

y

m

a

n

y

p

h

y

s

i

c

i

a

n

s

,

w

i

t

h

l

a

-

b

e

t

a

l

o

l

a

n

a

l

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

v

e

A

v

o

i

d

A

C

E

i

n

h

i

b

i

t

o

r

s

M

e

t

h

y

l

d

o

p

a

i

s

p

r

e

f

e

r

r

e

d

b

y

m

a

n

y

p

h

y

s

i

c

i

a

n

s

,

w

i

t

h

l

a

-

b

e

t

a

l

o

l

i

n

c

r

e

a

s

i

n

g

l

y

p

r

e

-

f

e

r

r

e

d

b

e

c

a

u

s

e

o

f

r

e

d

u

c

e

d

s

i

d

e

e

f

f

e

c

t

s

A

v

o

i

d

A

C

E

i

n

h

i

b

i

t

o

r

s

a

n

d

A

R

B

s

M

o

s

t

c

o

m

m

o

n

l

y

u

s

e

d

,

m

e

t

h

-

y

l

d

o

p

a

a

n

d

l

a

b

e

t

a

l

o

l

;

a

c

c

e

p

t

a

b

l

e

u

s

e

,

o

t

h

e

r

b

e

t

a

-

b

l

o

c

k

e

r

s

a

n

d

c

a

l

c

i

u

m

-

c

h

a

n

n

e

l

b

l

o

c

k

e

r

s

A

v

o

i

d

A

C

E

i

n

h

i

b

i

t

o

r

s

a

n

d

A

R

B

s

P

r

i

o

r

i

t

y

n

o

t

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

d

,

b

u

t

a

c

c

e

p

t

a

b

l

e

a

g

e

n

t

s

l

i

s

t

e

d

i

n

c

l

u

d

e

m

e

t

h

y

l

d

o

p

a

,

l

a

-

b

e

t

a

l

o

l

,

c

l

o

n

i

d

i

n

e

,

h

y

-

d

r

a

l

a

z

i

n

e

,

a

t

e

n

o

l

o

l

,

a

n

d

o

x

p

r

e

n

o

l

o

l

A

v

o

i

d

A

C

E

i

n

h

i

b

i

t

o

r

s

*

A

C

E

d

e

n

o

t

e

s

a

n

g

i

o

t

e

n

s

i

n

-

c

o

n

v

e

r

t

i

n

g

e

n

z

y

m

e

,

A

C

O

G

A

m

e

r

i

c

a

n

C

o

l

l

e

g

e

o

f

O

b

s

t

e

t

r

i

c

i

a

n

s

a

n

d

G

y

n

e

c

o

l

o

g

i

s

t

s

,

A

R

B

a

n

g

i

o

t

e

n

s

i

n

-

r

e

c

e

p

t

o

r

b

l

o

c

k

e

r

,

J

N

C

7

J

o

i

n

t

N

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

C

o

m

m

i

t

t

e

e

o

n

P

r

e

v

e

n

t

i

o

n

,

D

e

t

e

c

t

i

o

n

,

E

v

a

l

u

a

t

i

o

n

,

a

n

d

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

o

f

H

i

g

h

B

l

o

o

d

P

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

7

,

a

n

d

N

H

B

P

E

P

N

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

H

i

g

h

B

l

o

o

d

P

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

E

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

P

r

o

g

r

a

m

.

T

h

e

s

e

g

u

i

d

e

l

i

n

e

s

w

e

r

e

i

s

s

u

e

d

b

e

f

o

r

e

t

h

e

w

i

d

e

s

p

r

e

a

d

r

e

c

o

g

n

i

t

i

o

n

o

f

t

h

e

a

d

v

e

r

s

e

e

f

f

e

c

t

s

o

f

A

R

B

s

o

n

t

h

e

f

e

t

u

s

.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by erba epril on October 6, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

clinical practice

n engl j med 365;5 nejm.org august 4, 2011

445

Conclusions and

Recommendations

The woman with hypertension who is described

in the vignette should be counseled to use contra-

ception until she has undergone a prepregnancy

evaluation, including assessment of end-organ

damage; evaluation for identifiable causes of hy-

pertension, if suggested by her medical history,

physical examination, or laboratory testing; and

adjustment of antihypertensive therapy. If a revers-

ible cause of hypertension is identified, it should

be addressed before pregnancy. Before attempting

to conceive, the patient should replace the ACE

inhibitor with another antihypertensive agent that

is considered to be safe in pregnancy (methyldopa,

labetalol, or a long-acting calcium-channel block-

er), and she should be counseled regarding weight

reduction. Although some guidelines recommend

the first-line use of methyldopa on the basis of its

long safety record, we would generally use labet-

alol first, since data also support its safety, and

in practice we find it to be more effective and to

have fewer side effects than methyldopa.

The patient should be closely followed during

her pregnancy and be educated regarding the po-

tential risks of chronic hypertension in pregnan-

cy. Since she has a 5-year history of hypertension,

she is at increased risk for superimposed pre-

eclampsia.

2

In the absence of definitive recom-

mendations with respect to optimal blood-pres-

sure targets during pregnancy, we aim to adjust

medications to maintain blood pressure between

130/80 mm Hg and 150/100 mm Hg. Given the

need for careful prepregnancy planning and for

coordinated care during and after pregnancy for

women with chronic hypertension during their

reproductive years, we recommend interdisciplin-

ary care involving clinicians who are trained in

obstetrics and gynecology and those who are

trained in internal or family medicine.

Dr. Seely reports receiving an investigator-initiated grant from

Bayer Healthcare for a study involving postmenopausal women.

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was

reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with

the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

1. Sibai BM. Chronic hypertension in

pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:369-

77.

2. Sibai BM, Lindheimer M, Hauth J, et

al. Risk factors for preeclampsia, abruptio

placentae, and adverse neonatal outcomes

among women with chronic hypertension.

N Engl J Med 1998;339:667-71.

3. Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbo-

gast PG, et al. Major congenital malfor-

mations after first-trimester exposure to

ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2006;354:

2443-51.

4. Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in

unintended pregnancy in the United States,

1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health

2006;38:90-6.

5. Rey E, Couturier A. The prognosis of

pregnancy in women with chronic hyper-

tension. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;171:

410-6.

6. McCowan LM, Buist RG, North RA,

Gamble G. Perinatal morbidity in chronic

hypertension. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;

103:123-9.

7. Chappell LC, Enye S, Seed P, Briley

AL, Postin L, Sherman AH. Adverse peri-

natal outcomes and risk factors for pre-

eclampsia in women with chronic hyper-

tension. Hypertension 2008;51:1002-9.

8. Catov JM, Nohr EA, Olsen J, Ness RB.

Chronic hypertension related to risk for

preterm and term small for gestational age

births. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:290-6.

9. Ananth CV, Peltier MR, Kinzler WL,

Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. Chronic hy-

pertension and risk of placental abruption:

is the association modified by ischemic

placental disease? Am J Obstet Gynecol

2007;197(3):273.el-273.e7.

10. Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Sun L, Tro-

endle J, Willinger M, Zhang J. Prepreg-

nancy risk factors for antepartum still-

birth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol

2010;116:1119-26.

11. Wilson M, Morganti AA, Zervoudakis

I, et al. Blood pressure, the renin-aldos ter-

one system and sex steroids throughout

normal pregnancy. Am J Med 1980;68:97-

104.

12. August P, Lenz T, Ales KL, et al. Longi-

tudinal study of renin-angiotensin-aldos-

terone system in hypertensive pregnant

women: deviations related to superimposed

preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;

163:1612-21.

13. Abalos E, Duley L, Steyn DW, Hender-

son-Smart DJ. Antihypertensive drug ther-

apy for mild to moderate hypertension

during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2007;(1):CD002252.

14. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR,

et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint Na-

tional Committee on Prevention, Detec-

tion, Evaluation, and Treatment of High

Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA

2003;289:2560-72. [Erratum, JAMA 2003;

290:197.]

15. Woolcock J, Hennessy A, Xu B, et al.

Soluble Flt-1 as a diagnostic marker of

pre-eclampsia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynae-

col 2008;48:64-70.

16. Cockburn J, Moar VA, Ounsted M,

Redman CW. Final report of study on hy-

pertension during pregnancy: the effects

of specific treatment on the growth and

development of the children. Lancet 1982;1:

647-9.

17. Report of the National High Blood

Pressure Education Program Working

Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnan-

cy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:S1-S22.

18. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulle-

tins. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy.

Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:Suppl:177-85.

19. Rey E, LeLorier J, Burgess E, Lange IR,

Leduc L. Report of the Canadian Hyper-

tension Society Consensus Conference 3:

pharmacologic treatment of hypertensive

disorders in pregnancy. CMAJ 1997;157:

1245-54.

20. Tabacova S, Kimmel CA, Wall K, Han-

sen D. Atenolol development toxicity: ani-

mal-to-human comparisons. Birth De-

fects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2003;67:

181-92.

21. Aleksandrov NA, Fraser W, Audibert F.

Diagnosis, management, and evaluation of

hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Ob-

stet Gynaecol Can 2008;30:1000.

22. Collins R, Yusuf S, Peto R. Overview

of randomised trials of diuretics in preg-

nancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:17-

23.

23. Barr M Jr. Teratogen update: angio-

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by erba epril on October 6, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 365;5 nejm.org august 4, 2011

446

clinical practice

tensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Tera-

tology 1994;50:399-409.

24. Brent RL, Beckman DA. Angiotensin-

converting enzyme inhibitors, an embryo-

pathic class of drugs with unique proper-

ties: information for clinical teratology

counselors. Teratology 1991;43:543-6.

25. Gersak K, Cvijic M, Cerar LK. Angio-

tensin II receptor blockers in pregnancy:

a report of five cases. Reprod Toxicol

2009;28:109-12.

26. Serreau R, Luton D, Macher MA, Del-

ezoide AL, Garel C, Jacqz-Aigrain E. De-

velopmental toxicity of the angiotensin II

type 1 receptor antagonists during human

pregnancy: a report of 10 cases. BJOG

2005;112:710-2.

27. Bodnar LM, Ness RB, Markovic N,

Roberts JM. The risk of preeclampsia rises

with increasing prepregnancy body mass

index. Ann Epidemiol 2005;15:475-82.

28. American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists (ACOG). ACOG Committee

Opinion number 315: obesity in pregnan-

cy. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:671-5.

29. Brown MA, Hague WM, Higgins J, et

al. The detection, investigation and man-

agement of hypertension in pregnancy:

full consensus statement. Aust N Z J Ob-

stet Gynaecol 2000;40:139-55.

30. von Dadelszen P, Ornstein MP, Bull

SB, Logan AG, Koren G, Magee LA. Fall in

mean arterial pressure and fetal growth

restriction in pregnancy hypertension:

a meta-analysis. Lancet 2000;355:87-92.

31. Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-

dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in

women at high risk. N Engl J Med 1998;

338:701-5.

32. Levine RJ, Hauth JC, Curet LB, et al.

Trial of calcium to prevent preeclampsia.

N Engl J Med 1997;337:69-76.

33. Roberts JM, Myatt L, Spong CY, et al.

Vitamins C and E to prevent complications

of pregnancy-associated hypertension.

N Engl J Med 2010;362:1282-91.

34. Askie LM, Duley L, Henderson-Smart

DJ, Stewart LA. Antiplatelet agents for pre-

vention of pre-eclampsia: a meta-analysis

of individual patient data. Lancet 2007;369:

1791-8.

35. Hofmeyr GJ, Lawrie TA, Atallah AN,

Duley L. Calcium supplementation during

pregnancy for preventing hypertensive dis-

orders and related problems. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2010;(8):CD001059.

36. Sherman DJ, Arieli S, Tovbin J, Siegel

G, Caspi E, Bukovsky I. A comparison of

clinical and ultrasonic estimation of fetal

weight. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91:212-7.

37. Beardmore KS, Morris JM, Gallery

ED. Excretion of antihypertensive medi-

cation into human breast milk: a systematic

review. Hypertens Pregnancy 2002;21:85-

95.

38. National Library of Medicine Toxicol-

ogy Data Network. Drugs and lactation

database. (http://www.toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/

cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?LACT.)

39. Magee LA, Sibai B, Easterling T,

Walkinshaw S, Abalos E, von Dadelszen P.

How to manage hypertension in pregnan-

cy effectively. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011

May 4 (Epub ahead of print).

40. Hales CN, Barker DJ. The thrifty phe-

notype hypothesis. Br Med Bull 2001;60:

5-20.

41. The Society of Obstetricians and Gyn-

aecologists of Canada. Diagnosis, evalua-

tion, and management of the hypertensive

disorders of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol

Can 2008;30:S1-S48.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

The Journal requires investigators to register their clinical trials

in a public trials registry. The members of the International Committee

of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) will consider most reports of clinical

trials for publication only if the trials have been registered.

Current information on requirements and appropriate registries

is available at www.icmje.org/faq_clinical.html.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by erba epril on October 6, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Project Definition and DescriptionDokument9 SeitenProject Definition and DescriptionEileen VelasquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Foundations of Ekistics PDFDokument15 SeitenThe Foundations of Ekistics PDFMd Shahroz AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bos 22393Dokument64 SeitenBos 22393mooorthuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amit Singh RF EngineerDokument3 SeitenAmit Singh RF EngineerAS KatochNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stance AdverbsDokument36 SeitenStance Adverbsremovable100% (3)

- Solar SystemDokument3 SeitenSolar SystemKim CatherineNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAID BACK - Sunshine ReggaeDokument16 SeitenLAID BACK - Sunshine ReggaePablo ValdezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physics Tadka InstituteDokument15 SeitenPhysics Tadka InstituteTathagata BhattacharjyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Special Favors Given To Muhammad ( ) by Allah (Notes) - AuthenticTauheed PublicationsDokument10 Seiten6 Special Favors Given To Muhammad ( ) by Allah (Notes) - AuthenticTauheed PublicationsAuthenticTauheedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defender of Catholic FaithDokument47 SeitenDefender of Catholic FaithJimmy GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diversity Lesson Plan Angelica ViggianoDokument2 SeitenDiversity Lesson Plan Angelica Viggianoapi-339203904Noch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Appraisal System-Jelly BellyDokument13 SeitenPerformance Appraisal System-Jelly BellyRaisul Pradhan100% (2)

- Ereneta ReviewerDokument32 SeitenEreneta ReviewerAleezah Gertrude RaymundoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articles About Gossip ShowsDokument5 SeitenArticles About Gossip ShowssuperultimateamazingNoch keine Bewertungen

- SwimmingDokument19 SeitenSwimmingCheaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson PlansDokument9 SeitenLesson Plansapi-238729751Noch keine Bewertungen

- Securingrights Executive SummaryDokument16 SeitenSecuringrights Executive Summaryvictor galeanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Virtue-Ethical Approach To Education (By Pieter Vos)Dokument9 SeitenA Virtue-Ethical Approach To Education (By Pieter Vos)Reformed AcademicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Physiotherapy BPTDokument20 SeitenChest Physiotherapy BPTWraith GAMINGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blood Rage Solo Variant v1.0Dokument6 SeitenBlood Rage Solo Variant v1.0Jon MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adressverificationdocview Wss PDFDokument21 SeitenAdressverificationdocview Wss PDFabreddy2003Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assignments Is M 1214Dokument39 SeitenAssignments Is M 1214Rohan SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 01 Overview of Business AnalyticsDokument52 SeitenLecture 01 Overview of Business Analyticsclemen_angNoch keine Bewertungen

- Athletic KnitDokument31 SeitenAthletic KnitNish A0% (1)

- Raiders of The Lost Ark - Indiana JonesDokument3 SeitenRaiders of The Lost Ark - Indiana JonesRobert Jazzbob Wagner100% (1)

- Gurufocus Manual of Stocks: 20 Most Popular Gurus' StocksDokument22 SeitenGurufocus Manual of Stocks: 20 Most Popular Gurus' StocksCardoso PenhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Omnibus Motion (Motion To Re-Open, Admit Answer and Delist: Republic of The PhilippinesDokument6 SeitenOmnibus Motion (Motion To Re-Open, Admit Answer and Delist: Republic of The PhilippinesHIBA INTL. INC.Noch keine Bewertungen

- MKTG4471Dokument9 SeitenMKTG4471Aditya SetyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 Higher Order Differential EquationsDokument50 SeitenChapter 4 Higher Order Differential EquationsAlaa TelfahNoch keine Bewertungen

- SoapDokument10 SeitenSoapAira RamoresNoch keine Bewertungen