Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Anna Freud PDF

Hochgeladen von

elvinegunawanOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Anna Freud PDF

Hochgeladen von

elvinegunawanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

THE WRITINGS OF ANNA FREUD

In 8 Volumes, published by

International Universities Press Inc:

1. INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOANALYSIS

Lectures for Child Analysts and Teachers 1922-1935

2. THE EGO AND THE MECHANISMS OF DEFENCE (1936) 1966

3. INFANTS WITHOUT FAMILIES

Reports on the Hampstead Nurseries 1939-1945

4. INDICATIONS FOR CHILD ANALYSIS AND OTHER PAPERS 1945

5. RESEARCH AT THE HAMPSTEAD CHILD-THERAPY CLINIC AND

OTHER PAPERS 1956-1965

6. NORMALITY AND PATHOLOGY IN CHILDHOOD

Assessment of Development 1965

7. PROBLEMS OF PSYCHOANALYTIC TRAINING, DIAGNOSIS AND

THE TECHNIQUE OF THERAPY 1966-1970

8. PSYCHOANALYTIC PSYCHOLOGY OF NORMAL DEVELOPMENT

Publications in Chronological Order

1. Beating fantasies and daydreams. (1922) 1:137-57

2. Hysterical symptom in a child of two years and three months. (1923) 1:158-61

3. Child analysis, Four lectures on. (1927 [1927]) 1:3-62

4. Child Analysis, The theory of . (1928) [1927] 1:16275

5. Psychoanalysis for teachers and parents, Four lectures on (1930) 1:73-136

6. Psychoanalysis and the upbringing of the young child. (1934 [1932] )1:176-88

7. Infants without families: Reports on the Hampstead Nurseries (1939-45) written

in collaboration with Dorothy Burlingham. 3:3-681

8. Child analysis, Indications for. (1945) 4:3-38

9. Psychoanalytic study of infantile feeding disturbances, The. (1946) 4:39-59

10. Early education, Freedom from want in. (1946) 4:425-41

11. Child: an outline, The sleeping difficulties of the young. (1947) 4:605-9

12. Emotional and instinctual development. (1947) 4:458-88

13. Feeding habits, The establishment of. (1947) 4:442-57

14. Aggression in relation to emotional development: normal and pathological. (1949

[1947]) 4:489-97

15. Aggression, Notes on. (1949 [1948]) 4:60-74

16. August Aichhorn: July 28, 1878 October 17 1949. (1951) 4:625-38

17. Expert knowledge for the average mother. (1949) 4:528-44

18. Nursery school education: its uses and dangers. (1949) 4:545-59

19. Preadolescents relations to his parents, On certain difficulties in the. (1949) 4:95-

106

2

20. Social Maladjustment, Certain types and stages of. (1949) 4:75-94

21. Edith Buxbaums Your child makes sense, Foreword to. 4:610-13

22. Training analysis, The problem of. (1950 [1938]) 4:407-24

23. Psychoanalytic child psychology, The significance of the evolution of. (1950)

4:614-24

24. Child development, Observations on. (1951 [1950]) 4:143-62

25. Experiment in group upbringing, An. (1951) 4:163-229

26. Psychoanalysis to genetic psychology, The contribution of. (1951 [1950]) 4:107-

42

27. Bodily illness in the mental life of children, The role of. (1952) 4:260-79

28. Children, The child, visiting. (1952) 4:639-41

29. Ego and id: introduction to the discussion, The mutual influences in the

development of . (1952 [1951]) 4:30-44

30. Passivity, Studies in. (1952 [1949-1951]) 4:245-59

31. Teachers questions, Answering. (1952) 4:560-68

32. Alice Balints The psychoanalysis of the nursery, Introduction to. (1953)

4:642-44

33. Infant observation, Some remarks on. (1953 [1952]) 4:569-85

34. Instinctual drives and their bearing on human behavior. (1953 [1948]) 4:498-527

35. James Robertsons A two- year-old goes to hospital film review. (1953) 4:280-

92

36. Infantile neurosis: contribution to the discussion, Problems of. (1954) 4:327-55

37. Psychoanalysis and education. (1954) 4:317-26

38. Psychoanalysis: discussion, The widening scope of indications for. (1954) 4:356-

76

39. Technique in adult analysis, Problems of. (1954) 4:377-406

40. Rejecting mother, The concept of the. (1955 [1954]) 4:586-604

41. Borderline cases, The assessment of. (1956) 5:301-14

42. Joyce Robertsons A mothers observations on the tonsillectomy of her four-

year-old daughter, Comments on. (1956) 4:293-301

43. Psychoanalytic knowledge and its application to childrens services. (1964)

5:265-80

44. Child observation to psychoanalysis, The contribution of direct. (1957) 5:95-101

45. Gabriel Casusos Anxiety related to the discovery of the penis, Introduction

to. (1957) 5:473-75

46. Hampstead child-therapy course and clinic, The (1957) 5:3-8

47. Hampstead child-therapy clinic, Research projects of. (1957-1960) 5:9-25

48. Inconsistency in the mother as a factor in character development: a comparative

study of three cases by Anne-Marie Sandler, Elizabeth Daunton, and Annelise

Schnurmann, Introduction to (1957) 5:476-78

49. Marion Milners On not being able to paint, Foreword to. (1957) 5:488-92

50. Adolescence. (1958 [1957]) 5:136-66

51. Child observation and prediction of development: a memorial lecture in honor of

Ernst Kris. (1958 [1957]) 5:102-35

52. Chronic schizophrenia by Thomas Freeman, John L. Cameron, and Andrew

McGhie, Preface to. (1958) 5:493-95

3

53. John Bowlbys work on separation, grief, and mourning, Discussion of.

(1958.1960) 5:167-86

54. Child guidance clinic as a centre of prophylaxis and enlightenment. (1960 [1957])

5:281-300

55. Kata Levys Simultaneous analysis of a mother and her adolescent daughter: the

mothers contribution to the loosening of the infantile object tie, Introduction to.

(1960)5:479-82

56. Margarete Rubens Parent guidance in the nursery school, Foreword to. (1960

[1959]) 5:96-98

57. Nursery school: the psychological prerequisites, Entrance into. (1960) 5:315-35

58. Pediatricians questions, Answering. (1961 [1959]) 5:379-406

59. Children, Clinical problems of young. (1962) 5:352-68

60. Emotional and social development of young children, The. (1962) 5:336-51

61. Parent- infant relationship: contribution to the discussion, The theory of the. (1962

[1961]) 5:187-93

62. Pathology in childhood, Assessment of. (1962, 1964, 1966 [1965]) 5:26-59

63. Regression in mental development, The role of. (1963)5:407-19

64. Herman Nunberg, An appreciation of. (1964) 5:194-203

65. Psychoanalytic knowledge applied to the rearing of children. (1956) 5:265-80

66. Children in the hospital. (1965) 5:419-35

67. Family law, Three contributions to a seminar on. (1965 [1963-1964]) 5:436-59

68. Hampstead Psychoanalytic Index by John Boland and Joseph Sandler et al.,

Preface to The. (1965) 5:483-85

69. Heinz Hartmann: a tribute. (1965 [1964]) 5:499-501

70. Jeanne Lampl de Groots The development of the mind, Foreword to. (1965)

5:502-5

71. Metaphychological assessment of the adult personality: the adult profile. (1965)

5:60-75

72. Normality and Pathology in childhood: Assessment of Developments. (1965) 6:3-

273

73. Child analysis, A short history of. (1966) 7:48-57

74. Children, Services for underprivileged. (1966) 5:79-83

75. Ego and the Mechanisms of defence, The (1966 [1936]) 3:1-191

76. Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence, Forword to the 1966 edition of The.

(1966) 2:v-vi

77. Hartmanns ego psychology and the child analysts thinking, Links between.

(1966 [1964}) 5:204-20

78. Humberto Nageras Early childhood disturbances, the infantile neurosis, and the

adulthood disturbances, Foreword to. (1966 [1965]) 5:486-87 (This Foreword is

available at the end of this section)

79. Ideal psychoanalytic institute: a utopia, The. (1966) 7:73-93

80. Nursery school and child guidance clinic, Interactions between. (1966 [1965])

5:369-78

81. Obsessional neurosis: a summary of psychoanalytic views. (1966 [1965]) 5:242-

64

82. Psychoanalysis and family law. (1966 [1964]) 5:76-8

4

83. Psychoanalytic theory in the training of psychiatrists, The place of. (1966) 7:59-

72

84. Doctoral award address. (1967 [1964]) 5:507-16

85. Losing and being lost, About. (1967 [1953]) 4:302-16

86. Psychic trauma, comments on. (1967 [1964]) 5:221-41

87. Residential vs. foster care. (1967 [1966]) 7:223-39

88. Humberto Nageras Vincent van Gogh, A psychological Study, Foreword to.

(Book published in 1967) (This Foreword is available at the end of this section)

89. Acting out (1968 [1967]) 7:94-109

90. Child analysis, Indications and contraindications for. (1968) 7:110-23

91. Painter v. Bannister: Postscript by a psychoanalyst. (1968) 7:247-55

92. Psychoanalytic contribution to pediatrics, by Bianca Gordon, Foreword to

The. 7:268-71

93. Yale Law School, Address at commencement services of the. (1968) 7:256-62

94. Adolescence as a developmental disturbance. (1969 [1966]) 7:39-47

95. Difficulties in the path of psychoanalysis: a confrontation of past with present

views. (1969 [1968]) 7:124-56

96. Film review: John, seventeen months: nine days in a residential nursery by

James and Joyce Robertson. (1969) 7:240-46

97. Hampstead Clinic Psychoanalytic Library Series, Foreword to The. (1969

[1968]) 7:263-67 (Four volumes) (This Foreword is available at the end of this

section)

98. James Strachey. (1969) 7:277-80

99. Child analysis as a subspecialty of psychoanalysis. (1970) 7:204-22

100. Child analysis, Problems of termination in. (1970 [1957]) 7:3-21

101. Infantile neurosis: genetic and dynamic considerations, The. (1970) 7:189-203

102. Rene Spitz, A discussion with. (1970 [1966]) 7:22-38

103. Symptomatology of childhood: a preliminary attempt at classification, The.

(1970) 7:157-88

104. Termination in child analysis, Problems of. (1970 [1957]) 7:3-21

105. Wolf- Man by the Wolf-Man, Foreword to The (1971) 7:272-76

106. Aggression, Comments on. (1972 [1971]) 8:151-75

107. Psychoanalytical child psychology, normal and abnormal, the widening scope of

. (1972) 8:8-33

108. Childhood disturbances, Diagnosis and assessment of. (1974 [1954]) 8:34-56

109. Infantile neurosis, Beyond the. (1974) 8:75-81

110. Psychoanalytic view of developmental psychopathology, A. (1974 [1973]) 8:57-

74

111. Humberto Nageras Female Sexuality and the Oedipus Complex, Foreword

to. (Book published in 1974) (This Foreword is available at the end of this

section)

112. Children possessed. (1975) 8:300-6

113. Pediatrics and child psychology, On the interaction between. (1975) 8:285-96

114. Psychoanalytic practice and experience, Changes in. (1976 [1975]) 8:176-85

115. August Aichhorn. (1976 [1974]) 8-344-45

116. Dynamic psychology and education. (1976) 8:307-14

5

117. Psychoanalytic training, Remarks on problems of. (1976) 8:186-92

118. Humberto Nageras Obsessional Neuroses, Developmental Psychopathology,

Foreword to. (Book published in 1976) (This Foreword is available at the

end of this section)

119. Psychopathology seen against the background of normal development. (1976

[1975]) 8:82-95

120. Children, Concerning the relationship with. (1977) 8:297-99

121. Fears, anxieties, and phobic phenomena. (1977 [1976]) 8:193-200

122. Child analysis, The principal task of. (1978 [1977]) 8:96-109

123. Freuds writings, study guide to. (1978 [1977]) 8:209-76

124. Sigmund Freud Chair at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Inaugural lecture

for. (1978 [1977]) 8:334-43

125. Unveiling of the Freud statue, Address on the occasion of. (1978 [1977]) 8:331-

33

126. Child analysis as the study of mental growth, normal and abnormal. (1979)

8:119-36

127. Ernest Jones, Personal memories of. (1979) 8:346-53

128. Insight in psychoanalysis and psychotherapy: introduction, The role of. (1979

[1978]) 8:201-8

129. Lest we forget by Muriel Gardiner, Foreword to. (1979) 8:354-57

130. Mental health and illness in terms of internal harmony and disharmony. (1979)

8:110-18

131. Nursery school from the psychoanalytic point of view, The. (1979) 8:315-30

132. Analysis of a phobia in a five-year-old boy, Foreword to. (1980 [1979])

8:277-84

133. Normal child development, Introduction. (1980) 8:3-7

134. Topsy by Marie Bonaparte, Foreword to. (1980) 8:358-62

6

Forewords

To Humberto Nageras Early childhood disturbances, the infantile neurosis, and

the adulthood disturbances, problems of a developmental psychoanalytical

psychology

Dr. H. Nageras monograph bears witness to the child analysts dissatisfaction with the present mode

of diagnostic thinking. As stated by him, we are not content any longer to subsume all childhood

disorders under the all-embracing title of an infantile neurosis, as analysts tended to do in former

eras of psychoanalysis. Nor do we consider it an adequate solution to search for our answer to all

diagnostic questions in any one period of childhood, whether late, in the oedipal phase, as the classical

view sets out, or early in the first year of life, as more recent views assert. Nor are we ready to accept

the exclusive indictment of either faulty object relationships or faulty ego development, which many

modern authors treat as the only potential sources of trouble.

What the author of this monograph does to remedy the position is a careful apportioning of pathogenic

impact to external and internal interferences at any time of the childs life; the location of the internal

influences in any part of the psychic structure or in the interaction between any of the inner agencies;

and the building up, step by step, of an orderly sequence of childhood disorders, of which the infantile

neurosis is not the base, but the final, complex apex.

What satisfies the student of analysis in an exposition of this nature is the fact that on the one hand it is

rooted in the notion of a hypothetical norm of childhood development, while on the other hand it

establishes a hierarchy of disturbances which is valid for the period of immaturity and meaningful as a

forerunner of adult psychopathology.

Anna Freud

London, September 1965

To Humberto Nageras Vincent van Gogh, A Psychological Study

The letters by Vincent Van Gogh, on which this book is based, have moved the reading public by the

sincerity of feeling, the force of expression, the depth of human suffering and the surprising occasional

flashes of insight which are displayed in them. If, due to Van Goghs inevitably one-sided view of

events, they~ do not also forge the links between childhood and manhood, internal and external

experience, passion and its moral counterpart, this is precisely what the present author sets out to do.

His result is the striking image of a high-minded individuals struggle against the pressures within

himself, an image which would command our attention even if the man whose fate is traced were not

one of the admired creative geniuses of the last century.

In fact it is the essential conclusion implied by the author that even the highly prized and universally

envied gift of creative activity may fail tragically to provide sufficient outlets or acceptable solutions

for the relief of intolerable internal conflicts and overwhelming destructive powers active within the

personality.

7

To The Hampstead Clinic Psychoanalytic Library Series

The series of publications of which the present volume forms a part, wild be welcomed by all those

readers who are concerned with the history of psychoanalytic concepts and interested to follow the

vicissitudes of their fate through the theoretical, clinical and technical writings of psychoanalytic

authors. On the one hand, these fates may strike us as being very different from each other. On the

other hand, it proves not too difficult to single out some common trends and to explore the reasons

for them.

There are some terms and concepts which served an important function for psychoanalysis in its

earliest years because of t heir being simple and all-embracing such as for example the notion of a

complex. Even the lay public understood more or less easily that what was meant thereby was any

cluster of impulses, emotions, thoughts, etc. which have their roots in the unconscious and, exerting

their influence from there, give rise to anxiety, defences and symptom formation in the conscious

mind. Accordingly, the term was used widely as a form of psychological short -hand. Father-

Complex, Mother-Complex, Guilt -Complex, Inferiority-Complex, etc. became familiar

notions. Nevertheless, in due course, added psychoanalytical findings about the childs relationship

to his parents, about the early mother-infant tie and its consequences, about the complexities of

lacking self-esteem and feelings of insufficiency and inferiority demanded more precise

conceptualization. The very omnibus nature of the term could not but lead to its, at least partial,

abandonment. All that remained from it were the terms Oedipus-Complex to designate the

experiences centred around the triangular relationships of the phallic phase, and Castration-

Complex for the anxieties, repressed wishes, etc. concerning the loss or lack of the male sexual

organ.

If, in the former instance, a general concept was split up to make room for more specific meanings, in

other instances concepts took turns in the opposite direction. After starting out as concrete, well -

defined descriptions of circumscribed psychic events, they were applied by many authors to an ever-

widening circle of phenomena until their connotation became increasingly vague and imprecise and

until finally special efforts had to be made to re-define them, to restrict their sphere of application

and to invest them once more with precision and significance. This is what happened, for example,

to the concepts of Transference and of Trauma.

The concept and term transference was designed originally to establish the fact that the realistic

relationship between analyst and patient is invariably distorted by phantasies and object-relations

which stem from the patients past and that these very distortions can be turned into a technical tool

to reveal the patients past pathogenic history. In present days, the meaning of the term has been

widened to the extent that it comprises whatever happens between analyst and patient regardless of

its derivation and of the reasons for its happening.

A trauma or traumatic happening meant originally an (external or internal) event of a magnitude

with which the individuals ego is unable to deal, i.e. a sudden influx of excitation, massive enough

to break through the egos normal stimulus barrier. To this purely quantitative meaning of the term

were added in time all sorts of qualifications (such as cumulative, retrospective, silent, beneficial),

until the concept ended up as more or Less synonymous with the notion of a pathogenic event in

general.

Psychoanalytic concepts may be overtaken also by a further fate, which is perhaps of even greater

significance. Most of them owe their origin to a particular era of psychoanalytic theory, or to a

particular field of clinical application, or to a particular mode of technique. Since any of the

backgrounds in which they are rooted, are open to change, this should lead either to a corresponding

change in the concepts or to their abandonment. But, most frequently, this has failed to happen.

Many concepts are carried forward through the changing scene of psychoanalytic theory and practice

without sufficient thought being given to their necessary alteration or re-definition.

A case in kind is the concept of acting out. It was created at the very outset of technical thinking and

teaching, tied to the treatment of neurotic patients, and it characterized originally a specific reaction

of these patients to the psychoanalytic technique, namely that certain items of their past, when

retrieved from the unconscious, did not return to conscious memory but revealed themselves instead

8

in behaviour, were acted on, or acted out instead of being re membered. By now, this clear

distinction between remembering the recovered past and re-living it has been obscured; the term

acting out is used out of this context, notably for patients such as adolescents, delinquents or

psychotics whose impulse-ridden behaviour is part of their original pathology and not the direct

consequence of analytic work done on the egos defences against the repressed unconscious.

It was in this state of affairs that Dr H. Nagera initiated his enquiry into the history of psychoanalytic

thinking. Assisted by a team of analytic workers, trained in the Hampstead Child-Therapy Course

and Clinic, he set out to trace the course of basic psychoanalytic concepts from their first appearance

through their changes in the twenty-three volumes of the Standard Edition of the Complete

Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, i.e. to a point from where they are meant to be taken further

to include the writings of the most important authors of the post-Freudian era.

Dr Nageras aim in this venture was a fourfold one:

to facilitate for readers of psychoanalytic literature the understanding of psychoanalytic thought and of

the terminology in which it is expressed;

to understand and define concepts, not only according to their individual significance, but also

according to their relevance for the particular historical phase of psychoanalytic theory within which

they have arisen;

to induce psychoanalytic authors to use their terms and concepts more precisely with regard for the

theoretical framework to which they owe their origin, and to reduce thereby the many sources of

misunderstanding and confusion which govern the psychoanalytic literature at present;

finally, to create for students of psychoanalysis the opportunity to embark on a course of independent

reading and study, linked to a scholarly aim and designed to promote their critical and constructive

thinking on matters of theory-formation.

To Humberto Nageras Female Sexuality and the Oedipus Complex

Dr. H. Nageras book is a welcome reminder of the profitable years spent by him in and for the

Hampstead Child-Therapy Clinic. As expressed by him in his own introductory chapter, it was

especially his work with the Clinics Diagnostic Profile and his Chairmanship of the organizations

Clinical Concept Group which roused his interest in the limitations which still place the analysts

knowledge of female development far behind that gained of their male peers.

In his approach to the problems of female sexuality, Dr. Nagera is, thus, in a far more favorable

position than many analytic authors who have tackled this difficult subject before him. While those

who are only analysts of adults have to be content with reconstructing the childhood events which

are responsible for the deviations from normality in later life, Nagera, in his additional capacities as

child analyst and diagnostician of children, is privileged to see the developmental processes

themselves in action. To assess their beneficial or adverse effect for adult sexual behavior, he has at

his disposal not only the analysts familiar notions of fixation and regression, but also the concept of

progressive forward moves on prescribed developmental lines.

From firsthand experience and child-analytical cases, Nagera Constructs four of such lines for drive

development itself and demonstrates the possibility to examine each of them separately as to its

intactness or disturbance: change of object, of erotogenic Zone, of sexual and of active-passive

position. But, possibly more important and also more revolutionary than this, he proceeds to discuss

the intimate interaction of these with three other influences which simultaneously shape the

individuals sex life: the innate variations in the strength of the different component instincts; the

rate of progress on the line of ego development; and the environmental circumstances and

experiences which either favor or interfere with orderly developmental progress. With such a

multitude of forces at work, he does not find it surprising that the deviations from a norma l outcome

are as numerous and as complex as they prove to be.

He reverts repeatedly to one particular factor in female sexual development to which he attributes

outstanding significance, namely, the absence of a leading erotogenic zone during the little girls

9

positive Oedipus complex. Even after all the other agents in the situation are disentangled from each

other, he confesses himself still faced with the question how an organ appropriate for the discharge

of masculine-active excitation can be adapted to the same function regarding passive-feminine

strivings. He thus sees and describes the girls sexual life until and beyond puberty as one deprived

of an executive organ, a void which needs to be filled on the psychological side by means of

mechanisms and processes such as identification, desexualization, sublimation, etc.

While being guided through these developmental vicissitudes, readers can have every confidence in an

author who acknowledges the presence of obscurities where our present state of knowledge renders

them inevitable and who refuses to simplify matters which are, by nature, complex.

ANNA FREUD

London, 1974

To Humberto Nageras Obsessional Neuroses, Developmental Psychopathology

The motivation for this elaborate and painstaking piece of work is revealed clearly in the quotation

from Freud which initiates it. Humberto Nagera shares Freuds belief that the obsessional neurosis is

the most rewarding subject of analytic research, no other mental phenomenon displaying with equal

clarity the human quandary of relentless and unceasing battles between innate impulses and acquired

moral demands.

In the main part of his book, the author traces Freuds insights into the subject as they advanced and

broadened out from their first tentative beginnings in 1895 to some final pronouncements in 1939.

He orders these formulations under meaningful headings which range from merely terminological

and chronological concerns to the dynamic contributions made to the symptomatology by processes

in id, ego and superego.

From this invaluable guide for study, which no average reader could provide for himself, he proceeds

with similar thoroughness to the statements made by Freuds coworkers and immediate followers,

giving preference among them to two notable teachers and chroniclers of psychoanalysis: Hermann

Nunberg and Otto Fenichel. Nevertheless, in regard to these as well as to many of the other clinical

and theoretical contributors, he deplores the scarcity of original findings and characterizes the main

bulk of publications after Freud as merely amplifying and corroborating.

In his last chapters, Nagera enumerates the directions in which he feels the study of obsessional

phenomena may yield further profit. He notes among these clearer distinctions (1) between transient

obsessional symptoms as they arise during the ongoing conflicts of the anal-sadistic stage and the

obsessional neurosis proper, caused by later regression to that level; (2) between the consequences of

obsessionality for normal or abnormal character formation; (3) between obsessive characters on the

one hand and obsessive pathology on the other hand; and (4) between the harm done to a functioning

personality by hysterical interferences and that done by obsessional interferences. Finally, and most

important, he advocates a developmental approach to the etiological problems of the obsessional

neurosis that is, one in which not only a fixation point on the anal-sadistic level is considered of

major importance, but one in which the contributions from all, earlier or later, developmental phases

are given their due.

It is in this respect especially that the authors dealings with the problems of the obsessional neurosis

constitute a welcome continuation of his earlier explorations of developmental disturbances and

developmental conflicts as the possible forerunners of true neurotic conflicts, i.e., a continuation of

his efforts to create a developmental psychology which encompasses the normal and abnormal

problems of all stages of human growth.

10

Not Published (but available on this web site)

Freud, A., Nagera, H., Bolland, J., Anna Freuds Developmental Profile

(Modifications and Present Form)

In Collaboration with others

Bergmann, T. & Freud, A. (1965) Children in the Hospital., New York: Int. Univ.

Press.

Bonaparte, M., Freud, A., Kris, E., eds. (1954) Origins of Psychoanalysis:Letters to

Wilhelm Fliess, Drafts and Notes, 1887-1902, by Sigmund Freud., N.Y.: Basic

Books

Burlingham, D. and Freud, A. (1943) Infants Without Families., London: George

Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Burlingham, D. & Freud, A. (1949) Kriegskinder. (War Children.)London: Imago

Publishing Co.

Eissler, R.; Fre ud, A; Kris, M;Solnit, A. (eds) (1974) The Psychoanalytic Study of

the Child. Vol. 29., New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

Eissler, R;Freud, A; Kris, M; Solnit, A. (eds) (1973) The Psychoanalytic Study of

The Child, Vol. XXVII., New York: Quadrangle Books.

Eissler, R; Freud, A; Kris, M; & Solnit, A. (eds) (1973). The Psychoanalytic Study of

the Child. Vol. 28., New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

Eissler, R.; Freud, A.; Hartmann, H.; Kris, E. (1953). The Psychoanalytic Study of

the Child, Volume VIII, New York; International Univ. Press, Inc.

Eissler, R.; Fre ud, A.; Glover, E. et Al (1954). The Psychoanalytic Study of the

Child. Vol. IX., New York: Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler, R.; Fre ud, A.; Glover, E; et al. (1955). The Psychoanalytic Study of the

Child.,New York: Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler, R.; Fre ud, A.; Hartmann, H.; Kris, E. (1956). The Psychoanalytic Study of

the Child, Vol. XII., New York; Intl. Univ. Press.

Eissler, R.; Fre ud, A.; Hartmann, H.;Kris,E. (1958). The Psychoanalytic Study of the

Child, Vol. XIII., New York: Intl. Univ. Press.

Eissler,R.;Fre ud,A.;Hartmann,H.;Kris,E. (1959). The Psychoanalytic Study of the

Child, Vol. XIV., New York: Intl. Univ. Press.

Eissler,R.;Freud,A.;Hartmann,H.;Kris,E. (1960). The Psychoanalytic Study of the

Child, Vol. 15., New York:Int.Univ.Press.

Eissler,R, ;Fre ud,A.,Hartmann,H.,&Kris, M. (eds) (1961). The Psychoanalytic Study

of the Child, Vol. 16., New York:Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler, R. ;Fre ud,A.;et Al (1962). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. Vol. 17.,

New York: Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler,R., Freud, A., Hartmann, H., & Kris, M. (eds) (1963). The Psychoanalytic

Study of the Child, Volume XVIII., New York: Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler,Rl;Freud,A.; et al. (1963) The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. Vol. 18.,

New York: Int. Univ. Press.

11

Eissler,R.;Fre ud,A.; et al. (1964). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, Volume

XIX., New York: Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler,R.;Freud,A; et al. (1965). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, Volume

XX., New York: Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler,R.;Fre ud,A;et al. (1966). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, Volume

XXI., New York; Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler,R.;Fre ud,A.et al. (1967). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, Vol.XXII.,

New York; Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler,R.;Freud,A;et al. (1968). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, Vol. XXIII.,

New York: Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler, R.;Freud,A.; et al. (1969). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, Vol.

XXIV., New York:Int. Univ. Press.

Eissler,R.;Freud,A.;et al. (1970). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, Vol. XXV.,

New York:Int.Univ. Press.

Eissler,R.;Freud,A.;Kris,M.;Lustman,S; & Solnit, A. (eds.) (1971). The

Psychoanalytic Study of the Child., New York/Chicago: Quadrangle.

Eissler, R.;Freud,Al;Kriss,M.;Lustman,S.;& Solnit,A. (1972). The Psychoanalytic

Study of the Child., New York: Quadrangle Books.

Eissler, R.;Freud,A.;Kris,M.& Solnit, A. (eds) (1973). The Psychoanalytic Study of

the Child. Vol. XXVIII., New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

Goldstein, J., Freud,A. & Solnit, A. (1973). Beyond the Best Interests of the Child.,

New York; The Free Press.

Goldstein, J., Freud, A., & Solnit, Al (1979). Before the Best Interests of the Child.,

New York: The Free Press.

Freud A. The role of bodily illness in the mental life of children. Psychoanalytic

Study of the child 1952; 7:69-81

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- SBLC Format HSBC HKDokument2 SeitenSBLC Format HSBC HKWinengku50% (8)

- Freud, A. 1949 Some Clinical Remarks Concerning The Treatment of Cases of Male HomosexualityDokument22 SeitenFreud, A. 1949 Some Clinical Remarks Concerning The Treatment of Cases of Male HomosexualityKevin McInnes100% (1)

- The Chronicles of Narnia The Lion The Witch and The Wardobre (Movie Script)Dokument42 SeitenThe Chronicles of Narnia The Lion The Witch and The Wardobre (Movie Script)Israel OrtizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law Enforcement Summaries of The Findings in The Case Against Kimberly KesslerDokument119 SeitenLaw Enforcement Summaries of The Findings in The Case Against Kimberly KesslerKayla Davis67% (6)

- Todd Dufresne - Tales From The Freudian Crypt - The Death Drive in Text and Context (2000, Stanford University Press) PDFDokument124 SeitenTodd Dufresne - Tales From The Freudian Crypt - The Death Drive in Text and Context (2000, Stanford University Press) PDFGichin Funakoshi100% (2)

- DPWH V CMCDokument4 SeitenDPWH V CMCAnonymous yEnT80100% (2)

- Freud and His Subjects: Dora and The Rat Man As Research ParticipantsDokument13 SeitenFreud and His Subjects: Dora and The Rat Man As Research ParticipantsJonathan BandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Robert WallersteinDokument26 SeitenRobert WallersteinRocio Trinidad100% (1)

- Magagna, J. and Pepper Goldsmith, T. (2009) - Complications in The Development of A Female Sexual Identity.Dokument14 SeitenMagagna, J. and Pepper Goldsmith, T. (2009) - Complications in The Development of A Female Sexual Identity.Julián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mourning Analysis The Post-Termination Phase. Heeather CraigeDokument44 SeitenMourning Analysis The Post-Termination Phase. Heeather CraigeFredy Alberto Gomez GalvisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexual Indifference and Lesbian RepresentationDokument24 SeitenSexual Indifference and Lesbian RepresentationA Guzmán MazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is PsychoanalysisDokument5 SeitenWhat Is PsychoanalysisNice tuazonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jacques Lacan - Family Complexes in The Formation of The IndividualDokument102 SeitenJacques Lacan - Family Complexes in The Formation of The IndividualChris JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- BFI ScoringDokument2 SeitenBFI ScoringelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hieros Gamos PDFDokument72 SeitenHieros Gamos PDFJoel LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labour Law-Unit 3 - Part 2-Dismissal at CommonlawDokument13 SeitenLabour Law-Unit 3 - Part 2-Dismissal at CommonlawLecture WizzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blass-Spilitting - 2015-The International Journal of PsychoanalysisDokument17 SeitenBlass-Spilitting - 2015-The International Journal of PsychoanalysisAvram OlimpiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DREAMSDokument148 SeitenDREAMSJavier Ugaz100% (1)

- The Fear of Looking or Scopophilic — Exhibitionistic ConflictsVon EverandThe Fear of Looking or Scopophilic — Exhibitionistic ConflictsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Care TheoryDokument7 SeitenSelf Care TheoryMardiah Fajar KurnianingsihNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Psychology in North America, History Of: Donald K Routh, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USADokument7 SeitenClinical Psychology in North America, History Of: Donald K Routh, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USARanjan Kumar SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Identity Crisis in The Age of Globalization and TechnologyDokument7 SeitenCultural Identity Crisis in The Age of Globalization and TechnologySudheesh KottembramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychology, Development and Social Policy in India: R. C. Tripathi Yoganand Sinha EditorsDokument327 SeitenPsychology, Development and Social Policy in India: R. C. Tripathi Yoganand Sinha Editorsgarima kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freud & Bullitt-An Unknown ManuscriptDokument37 SeitenFreud & Bullitt-An Unknown ManuscriptRichard G. Klein100% (1)

- LACAN, Jacques - Seminar 4 - The Object Relation - A. R. PriceDokument461 SeitenLACAN, Jacques - Seminar 4 - The Object Relation - A. R. PriceMeu penis giganteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Un Modelo Sociológico para Investigar Las Relaciones Afectivosexuales - A Sociological Model For Investigating Sex and RelationshipsDokument32 SeitenUn Modelo Sociológico para Investigar Las Relaciones Afectivosexuales - A Sociological Model For Investigating Sex and RelationshipsPablo Barrientos LaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malcolm Pines - The Group-As-A-whole Approach in Foulksian Group Analytic PsychotherapyDokument5 SeitenMalcolm Pines - The Group-As-A-whole Approach in Foulksian Group Analytic PsychotherapyNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Martin S. Bergmann 2008 - The Mind Psychoanalytic Understanding Then and Now PDFDokument28 SeitenMartin S. Bergmann 2008 - The Mind Psychoanalytic Understanding Then and Now PDFhioniamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Melancholia in The Writing of A Sixteent PDFDokument5 SeitenMelancholia in The Writing of A Sixteent PDFatabeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roger Perron - Idea/RepresentationDokument5 SeitenRoger Perron - Idea/RepresentationAustin E BeckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic 3 Rollo MayDokument34 SeitenTopic 3 Rollo MayGremond PanchaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vangelis AthanassopoulosDokument10 SeitenVangelis AthanassopoulosferrocomolusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Identity and Migration An IntroductionDokument14 SeitenIdentity and Migration An IntroductionconexhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hoffman - The Myths of Free AssociationDokument20 SeitenHoffman - The Myths of Free Association10961408Noch keine Bewertungen

- FreudDokument28 SeitenFreudLuis ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- History: 141 True and False Self (1960)Dokument7 SeitenHistory: 141 True and False Self (1960)fazio76Noch keine Bewertungen

- Belk - Possessions and The Extended SelfDokument31 SeitenBelk - Possessions and The Extended SelfSharron ShatilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Horkheimer, Interview, Contretemp JournalDokument4 SeitenHorkheimer, Interview, Contretemp JournalstergiosmitasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kutash-Wolf. Psychoanalysis in GroupsDokument12 SeitenKutash-Wolf. Psychoanalysis in GroupsJuanMejiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychoanalytic Explorations in Music ReviewDokument4 SeitenPsychoanalytic Explorations in Music Reviewgonzalovillegas1987Noch keine Bewertungen

- PharmakonDokument4 SeitenPharmakonAmin Mofreh100% (1)

- Hermine Hug-Hellmuth, The First Child PsychoanalystDokument6 SeitenHermine Hug-Hellmuth, The First Child Psychoanalystrenato giacomini100% (1)

- Narrative Identity: Current Directions in Psychological Science June 2013Dokument8 SeitenNarrative Identity: Current Directions in Psychological Science June 2013Chemita UocNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ma Psychoanalysis History and Culture Handbook 201213Dokument53 SeitenMa Psychoanalysis History and Culture Handbook 201213Attila Attila AttilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pop Culture Celebrity Addiction SyndromeDokument7 SeitenPop Culture Celebrity Addiction SyndromeClinton HeriwelsNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Conversatio A Conversation With Gayatri Chakravorty Spivakspivak - Politics and The ImaginationDokument17 SeitenA Conversatio A Conversation With Gayatri Chakravorty Spivakspivak - Politics and The ImaginationJinsun YangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rene SpitzDokument16 SeitenRene SpitzagelvezonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stucke 2003Dokument14 SeitenStucke 2003Алексей100% (1)

- Scharff Sobre FairbairnDokument21 SeitenScharff Sobre FairbairnAntonio TariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quotes From Lacan's First SeminarDokument8 SeitenQuotes From Lacan's First SeminarMythyvalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dicionário Crítico de PsicoanáliseDokument244 SeitenDicionário Crítico de PsicoanáliseMarcia Borba100% (1)

- GR 1103 EvansDokument14 SeitenGR 1103 EvansJoão Vitor Moreira MaiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexuality in The Formation of The SubjectDokument13 SeitenSexuality in The Formation of The Subjectzizek1234Noch keine Bewertungen

- Authenticity. The Person As His or Her Own AuthorDokument16 SeitenAuthenticity. The Person As His or Her Own Authorjv_psi100% (1)

- Berry, J. W. (2001) - A Psychology of ImmigrationDokument17 SeitenBerry, J. W. (2001) - A Psychology of ImmigrationFlorin Nicolau100% (1)

- A General Introduction To PsychoanalysisDokument18 SeitenA General Introduction To PsychoanalysisTrần Nhật Anh0% (1)

- Stijn Vanheule-Qualitative Research Its Relation To Lacanian PsychoanalysisDokument7 SeitenStijn Vanheule-Qualitative Research Its Relation To Lacanian PsychoanalysisFengNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychoanalytic Contributions of Karl Abraham To The Freudian LegacyDokument5 SeitenPsychoanalytic Contributions of Karl Abraham To The Freudian LegacyPsychologydavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psicología Comunitaria y Políticas Sociales: Institucionalidad y Dinámicas de Actores - Jaime Alfaro InzunzaDokument10 SeitenPsicología Comunitaria y Políticas Sociales: Institucionalidad y Dinámicas de Actores - Jaime Alfaro InzunzaNatalia Teresa Quintanilla MoyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shaping MasculinityDokument21 SeitenShaping MasculinityNenad SavicNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Work of Hypochondria - AisensteinDokument19 SeitenThe Work of Hypochondria - AisensteinJonathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cambridge Foucault Lexicon - TransgressionDokument8 SeitenThe Cambridge Foucault Lexicon - TransgressionpastorisilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urry - A History of Field MethodDokument27 SeitenUrry - A History of Field Methodภูโขง บึงกาฬNoch keine Bewertungen

- Erich Fromm Humanistic Psychoanalysis PDFDokument51 SeitenErich Fromm Humanistic Psychoanalysis PDFkay lyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theoretical Paradigms On Society and Social BehaviorDokument27 SeitenTheoretical Paradigms On Society and Social BehaviorLeon Dela TorreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Thibierge MorinDokument15 SeitenSelf Thibierge Morinloxtrox1Noch keine Bewertungen

- D. Steiner - Illusion, Disillusion and Irony in PsychoanalysisDokument21 SeitenD. Steiner - Illusion, Disillusion and Irony in PsychoanalysisHans CastorpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stages of ChangeDokument3 SeitenStages of Changeelvinegunawan100% (1)

- SignDokument12 SeitenSignelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- "SELFOBJECT" NEEDS IN KOHUT'S SELF PsychologyDokument37 Seiten"SELFOBJECT" NEEDS IN KOHUT'S SELF PsychologyOana Panescu100% (1)

- Amplify GrantDokument6 SeitenAmplify GrantelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classification of Sleep DisordersDokument15 SeitenClassification of Sleep Disorderselvinegunawan100% (1)

- Trans Genderqueer and Queer Terms GlossaryDokument9 SeitenTrans Genderqueer and Queer Terms GlossaryJacob LundquistNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supplementary Web Content ReferencesDokument47 SeitenSupplementary Web Content ReferenceselvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Locke-Wallace Short Marital-Adjustment TestDokument16 SeitenLocke-Wallace Short Marital-Adjustment TestelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classification of Sleep DisordersDokument15 SeitenClassification of Sleep Disorderselvinegunawan100% (1)

- The Reliability of Relationship SatisfactionDokument10 SeitenThe Reliability of Relationship SatisfactionelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1981 - Lock-Wallace Marital Adjustment Test Reconsidered-Psychometic Findings As Regards Its Reliability & Factorial Validity - Cross SharpleyDokument5 Seiten1981 - Lock-Wallace Marital Adjustment Test Reconsidered-Psychometic Findings As Regards Its Reliability & Factorial Validity - Cross SharpleyelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qual Saf Health Care 2007 Batalden 2 3Dokument3 SeitenQual Saf Health Care 2007 Batalden 2 3elvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Association of Marital Relationship and Perceived Social Support With Mental Health of Women in PakistanDokument13 SeitenThe Association of Marital Relationship and Perceived Social Support With Mental Health of Women in PakistanelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Marriage A Root of Current Physiological and Psychosocial Health BurdensDokument4 SeitenEarly Marriage A Root of Current Physiological and Psychosocial Health BurdenselvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 - Pregnancy Outcomes Following Maternal Exposure To Second-Generation Antipsychotics Given With Other Psychotropic DrugsDokument11 Seiten2014 - Pregnancy Outcomes Following Maternal Exposure To Second-Generation Antipsychotics Given With Other Psychotropic Drugselvinegunawan100% (1)

- No Pertanyaan Y T: Self Reporting Questionanaire-29Dokument1 SeiteNo Pertanyaan Y T: Self Reporting Questionanaire-29elvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bhutan Index HappinessDokument3 SeitenBhutan Index HappinesselvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report of Drug S TestingDokument2 SeitenReport of Drug S TestingelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of Personality On Adherence To Methadone Maintenance Treatment in Methadone Clinic in Hasan Sadikin General HospitalDokument1 SeiteThe Influence of Personality On Adherence To Methadone Maintenance Treatment in Methadone Clinic in Hasan Sadikin General HospitalelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nicotinic AgonistsDokument48 SeitenNicotinic AgonistselvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- QualityCare B.defDokument50 SeitenQualityCare B.defKevin WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qual Saf Health Care 2007 Batalden 2 3Dokument3 SeitenQual Saf Health Care 2007 Batalden 2 3elvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SCL90Dokument82 SeitenSCL90elvinegunawan60% (5)

- Form PenilaianDokument72 SeitenForm PenilaianelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- APA SAMHSA Minority FellowshipDokument1 SeiteAPA SAMHSA Minority FellowshipelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Student AwardsDokument1 SeiteMedical Student AwardselvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter of Intent: Board Certified Non Board Certified Board Eligible (Date of Scheduled Exam) Individual: GroupDokument2 SeitenLetter of Intent: Board Certified Non Board Certified Board Eligible (Date of Scheduled Exam) Individual: GroupelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- HebefrenikDokument37 SeitenHebefrenikelvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Pone 0018241Dokument7 SeitenJournal Pone 0018241elvinegunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Origin of The Ngiri Vikuu Occult Society in CameroonDokument3 SeitenThe Origin of The Ngiri Vikuu Occult Society in CameroonDr. Emmanuel K FaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Othello CharactersDokument3 SeitenOthello Charactersapi-300198755Noch keine Bewertungen

- Second Sex - de Beauvoir, SimoneDokument20 SeitenSecond Sex - de Beauvoir, SimoneKWins_1825903550% (1)

- Licaros Vs GatmaitanDokument11 SeitenLicaros Vs GatmaitanheyoooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Major TeachingsDokument19 SeitenMajor TeachingsRicha BudhirajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Battle of Bull Run-WorksheetDokument2 SeitenFirst Battle of Bull Run-WorksheetnettextsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Past Perfect Simple and Past Perfect Continuous - ADokument2 SeitenPast Perfect Simple and Past Perfect Continuous - AFatima VenturaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islam The BeautyDokument2 SeitenIslam The BeautyZannatul FerdausNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cv. Juanda1Dokument2 SeitenCv. Juanda1robyNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Brenton Holmes, 3rd Cir. (2010)Dokument3 SeitenUnited States v. Brenton Holmes, 3rd Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fahrenheit 451 Book ReviewDokument3 SeitenFahrenheit 451 Book ReviewBuluc George PaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon Midterm ReviewerDokument20 SeitenOblicon Midterm ReviewerJanelle Winli LuceroNoch keine Bewertungen

- TPS10 Armada RulesDokument10 SeitenTPS10 Armada RulesTom MaxsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lines Plan and Main ParticularsDokument17 SeitenLines Plan and Main ParticularsShaik AneesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iii. Prescription A. Types of Prescription 1. AcquisitiveDokument5 SeitenIii. Prescription A. Types of Prescription 1. Acquisitivemailah awingNoch keine Bewertungen

- OTv 7 HG 5 YAf TV RJJaDokument8 SeitenOTv 7 HG 5 YAf TV RJJaKuldeep JatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Animal Farm SummaryDokument1 SeiteAnimal Farm SummaryPI CubingNoch keine Bewertungen

- DepEd Child Protection PolicyDokument5 SeitenDepEd Child Protection PolicyLyn Evert Dela Peña100% (6)

- P You Must Answer This QuestionDokument6 SeitenP You Must Answer This QuestionzinminkyawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law Test BankDokument260 SeitenCriminal Law Test BankClif Mj Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

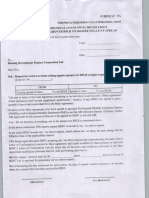

- Format 9A: Applicable For Individual Loans Switchover From Existing Negative Spreadover RPLR To Higher Negative SpreadDokument1 SeiteFormat 9A: Applicable For Individual Loans Switchover From Existing Negative Spreadover RPLR To Higher Negative SpreadANANDARAJNoch keine Bewertungen

- VSB Docket HearingDokument4 SeitenVSB Docket HearingWSLSNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Danilo Rodriguez, 833 F.2d 1536, 11th Cir. (1987)Dokument3 SeitenUnited States v. Danilo Rodriguez, 833 F.2d 1536, 11th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1987 Constitution Legislative Department NotesDokument9 Seiten1987 Constitution Legislative Department NotesjobenmarizNoch keine Bewertungen