Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Jakobson's Remarks On The Evolution of Russian (How To Read Remarques Sur L'evolution Phonologique Du Russe Comparée À Celle Des Autres Langues Slaves

Hochgeladen von

Ronald0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

102 Ansichten30 Seiten- Jakobson's 1929 work on the evolution of Russian and Slavic languages applied structural phonological analysis to historical linguistics, arguing that certain systematic principles determined how Common Slavic split into language zones rather than random changes.

- His work received less recognition than expected due to the original Russian version being lost in WWII and only a difficult French translation surviving. Trubetzkoy noted Jakobson's overly metaphorical style made it hard to read.

- Jakobson analyzed how different orders of sound changes like loss of final vowels and development of palatalized consonants led language zones to resolve "phonological conflicts" differently, influencing their structures. His analysis focused on relative chronology of

Originalbeschreibung:

Discussion of Jakobson's 1929 book on diachronic linguistics. Use of conflicts to present differing relative chronologies.

Originaltitel

“Jakobson’s Remarks on the Evolution of Russian (How to read Remarques sur l’evolution phonologique du russe comparée à celle des autres langues slaves”

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument melden- Jakobson's 1929 work on the evolution of Russian and Slavic languages applied structural phonological analysis to historical linguistics, arguing that certain systematic principles determined how Common Slavic split into language zones rather than random changes.

- His work received less recognition than expected due to the original Russian version being lost in WWII and only a difficult French translation surviving. Trubetzkoy noted Jakobson's overly metaphorical style made it hard to read.

- Jakobson analyzed how different orders of sound changes like loss of final vowels and development of palatalized consonants led language zones to resolve "phonological conflicts" differently, influencing their structures. His analysis focused on relative chronology of

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

102 Ansichten30 SeitenJakobson's Remarks On The Evolution of Russian (How To Read Remarques Sur L'evolution Phonologique Du Russe Comparée À Celle Des Autres Langues Slaves

Hochgeladen von

Ronald- Jakobson's 1929 work on the evolution of Russian and Slavic languages applied structural phonological analysis to historical linguistics, arguing that certain systematic principles determined how Common Slavic split into language zones rather than random changes.

- His work received less recognition than expected due to the original Russian version being lost in WWII and only a difficult French translation surviving. Trubetzkoy noted Jakobson's overly metaphorical style made it hard to read.

- Jakobson analyzed how different orders of sound changes like loss of final vowels and development of palatalized consonants led language zones to resolve "phonological conflicts" differently, influencing their structures. His analysis focused on relative chronology of

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 30

Jakobsons Remarks on the

Evolution of Russian and the Slavic

Languages:

Its significance and How to Read it

Presenter: Ronald Feldstein

1

2

3

Jakobsons Purpose

To bring structural methods of phonological analysis to

historical linguistics.

de Saussurefelt that linguistic history was due to haphazard

accidents.

Jakobson tried to prove that certain systematic principles

determined the split of Common Slavic into zones and that it

was not haphazard.

Jakobson (1929): the first phonemic linguistic history, giving

systematic reasons for sound changes; rejects blind changes.

4

Jakobsons work never got the recognition some

expected. Why?

1. The Russian original was lost in World War II and

only a French translation survived.

2. Trubetzkoy told Jakobson his style was overly

metaphorical and difficult, relying on terms like the

battle, duel, or conflict between phonological

oppositions.

5

Sample of Trubetzkoys comments in a letter to Jakobson:

All these defects, the result of haste and not enough

restraint when you deal with an extremely strong torrent of

ideas, become twice as bad in translation.

Because of all this, the book is very hard to read. To some

extent, it's the Russian linguistic tradition. But your

unreadability is different than Fortunatov's or Bubrikh's.

The thoughtful reader will overcome this difficulty, and if

not for the stilted translation, your book would have made a

great impression. But only a thoughtful reader will see and

appreciate this, and that's the minority. A mediocre linguist

(like Beli) won't understand a thing. By the way, with a little

effort you could have made it comprehensible even for every

mediocre linguist. Of course, you'll never change.

6

Original Russian:

7

Jakobsons Letter in Reply to Trubetzkoy:

Unfortunately, I have to agree with what you say about my

written style. True, the translation takes a lot away from the

book. The original is much more succinct. But, my inability to

develop a thought remains.

Only its not the result of haste. On the contrary, the more I

work on something, the more attention it gets. If I re-work a

chapter, I inadvertently fill it with more and more ideas that

come into my mind.

If you wish, its the Ushakov School. Not the linguist Dmitry

Ushakov, but the icon painter Simon Ushakov. The sense of how

one section relates to the whole work gets lost. However

harmful this is to my work, its extremely hard to get rid of it

psychologically, except by writing short articles on single

subjects.

8

Original of Jakobsons reply:

9

Metaphors for Relative Chronology

Jakobsons difficult metaphors often are ways of expressing relative

chronology. Almost everything in the book hinges on whether

certain things occur before or after the loss of final short vowels

(called jers) in Slavic languages.

One ordering can mean an absence of conflict and that certain

types of phonological changes result, but the opposite ordering

means that conflict and other sorts of linguistic changes occur.

10

Jakobsons Method:

Lay out general linguistic principles for several

phonological features which either could not co-occur in

the same system or had to co-occur.

Jakobson thought that these were universals or near

universals, that applied to most or all world languages,

not only Slavic.

Each group of features produced a unique combination of

features in the various Slavic zones.

Before looking at these linguistic rules, lets briefly review

the Slavic linguistic map and the major language areas.

11

12

13

General Stages in Jakobsons Concept of Phonological Change

1. A change occurs that may be very common or near universal, but is not

necessarily the result of incompatible features. One assumes that the

phonological features prior to this change are internally compatible and

the system is in balance. (Example: loss of final short high jer vowels.

Possible cause: reduction of redundancy in allegro style of speech.)

2. The new change may then cause the coexistence of features which are

incompatible or universally inadmissible in natural languages. In this case,

the language development is not haphazard, but responds to the first

change on the basis of its system at the given time. Or, it anticipates the

change from a nearby dialect and changes the system in advance.

3. In a group of contiguous related languages (like Slavic), the relative

moment of the first change produces different types of compatible or

incompatible feature combinations, so relative chronology takes on a

great importance.

14

The phonological trigger for change in all Slavic

zones: loss of weak jers (short high vowels, front and

back: and , as in [dan] vs. [dan]. This started in

the SW of Slavic, moving NW and East.

Prior to this, consonants before front vowels had

become palatalized, symbolized here by [n].

If the vowels / were to drop, a new kind of

palatalized phonemic opposition could come about.

This is characteristic of Russian and some other Slavic

languages, but not Slovene, Serbian, Croatian, etc.

Jakobsons principles of compatibility address this.

15

Most of the principles address how vowel accents

interface with the possibility of newly palatalized

consonants, coming from jer-fall.

In Common Slavic, the first syllable could have two

different accented types: rising and falling. Vowels

could be long or short, but had to be long for the

rising/falling opposition. Jakobson treated long

vowels as consisting of two halves or moras: = .

Falling tone was equal to accent on the first mora

()and rising was an accent on the second mora

(). Accents on other syllables were set off by rising

tone, so the accent was called tonal.

16

Rule 1: Vowel tone requires quantity (2 moras) and implies

that stressed vs. unstressed is based on high pitch or

tone, not loudness.

Rule 2. Phonemic dynamic stress (non-tonal) and vowel

quantity are mutually exclusive, because if there are

moraic longs with free stress, the different stresses equal

tone. (A language cant have free stress across syllables but

not inside moraic syllables.)

Rule 3: If a moraic tonal opposition inside a syllable is

absent, then stressed vs. unstressed must be based on

loudness, not vowel tone. (Although pitch can exist non-

phonemically.)

Rule 4: Consonant palatalization and vocalic tone are

mutually exclusive. A language cant have both

consonantal and vocalic tone. Relates to jer-fall.

17

18

If the language had tone to start with and then

consonant palatalization developed at the moment

of jer-fall, it was possible for the language to have

conflicting features that could not combine, so

something had to be lost.

Conflicting features meant that the language had

to get rid of one or the other, or both.

A Slavic language could either avoid all conflicts by

changing its system prior to jer-fall, or deal with a

set of phonological conflicts otherwise.

19

Jakobson named two types of conflict: A

occurred if consonant and vocalic tone clashed in

the same system (due to palatalizing jer-fall against

the backdrop of tonal accent).

In this case, the vowel tone was lost, but then

vowel quantity was paired with non-tonal accent,

which also could not combine, producing Conflict

B. This meant that either phonemic vowel

quantity or phonemic stress accent (non-tonal)

could not co-exist. One or both had to be

eliminated.

20

The major Slavic zones changed their systems either

before or after jer-fall.

Thus, Jakobsons theory of phonological conflicts can

be treated as differences of relative chronology.

Jakobsons zones can be depicted as an isogloss for

jer-fall that is moving from SW to both Northeast and

East, and which may or may not be preceded by

another isogloss for loss of phonemic tone.

You can analogize it to a race where the person in the

lead changes back and forth.

The following charts shows the direction of these

changes across the Slavic map.

21

22

23

The SW (Slovene, Croatian/Serbian/Bosnian) was the

only zone that kept vocalic tone and has the least

evidence of consonantal palatalization.

Jakobson assumed that this zone eliminated consonantal

palatalization prior to jer-fall, so no conflicts occurred

here. I.e. they depalatalized all consonants preceding

front vowels, never developing the phonemic

opposition.

24

The SW relative chronology looks like this:

1. Loss of palatalized consonants before front

vowels. dan/dan dan/dan

2. Fall of weak jers: merger into dan.

The two areas which experienced jer-fall after the SW

are Czech/Slovak to the north, and West Bulgarian to

the east.

They lost both consonant palatalization and vowel

tone, evidence of Jakobsons Conflict A.

In Conflict B, Czech/Slovak retained quantity and lost

phonemic stress, but West Bulgarian lost phonemic

quantity, keeping intensity stress.

25

The relative chronology here would be somewhat the

opposite of the SW:

1. Jer-fall, with potentially phonemic consonant

tonality, clashing with vowel tone.

2. Loss of vowel tone and change to dynamic stress;

loss of consonant palatalization.

3. Conflict of quantity and dynamic stress, in favor of

quantity (Czech/Slovak) or stress (West Bulgarian).

Let us now contrast this with the extreme opposite

end of the Slavic map, represented by the NE

(Russian and Belarusian).

26

In Russian/Belarusian, we find full systems of consonant

palatalization and dynamic stress.

This implies no phonological conflict.

Jer-fall must have been preceded by the loss of

phonemic tone and quantity, leaving a clear path for the

institution of phonemic palatalization and dynamic

stress.

Implied relative chronology:

1. Loss of vocalic tone (change to dynamic stress) and

loss of quantity.

2. Jer-fall, with introduction of phonemic consonant

palatalization.

27

There were important nuances in the intervening

languages, such as East Bulgarian and Ukrainian.

They can be viewed as transitional zones between

intermediate Czech/Slovak/West Bulgarian and Russian.

Consonant palatalization was not eliminated

phonemically, but was partially curtailed in certain

environments:

In Ukrainian and East Bulgarian, the opposition of

consonant palatalization was lost in front of certain vowel

groups, such as mid vowels.

In Jakobsons terms, Conflict A may have occurred, but

with less drastic results than in Czech. So, relative

chronology alone does not address all of the nuances of

development in all of the Slavic languages.

28

Nevertheless, Jakobsons system give us a very useful tool

for understanding the major developments in the change

of Common Slavic to the modern Slavic languages.

Linguists have written papers pointing out individual

errors in Jakobsons general principles.

Pavle Ivi pointed out that dynamic stress and quantity co-

exist in a small dialect zone of Montenegro (Old

tokavian), without the new tone of Neo-tokavian).

However, this does not negate the value of Jakobsons

analysis, which accurately applies to virtually all of the

Slavic zones in terms of the phonemic systems involved.

It is one of the most important pioneering works in the

history of linguistics and certainly the most important

work of historic linguistics of the Prague School.

29

Appendix

Table of 3 feature combination types

Mutually exclusive features

(Cannot co-occur)

1. Consonant Palatalization and

Vocalic Tone

E.g. Russian, Polish, Bulgarian have

only the former (consonant

palatalization);

Slovene/Serbian/Croatian/Bosnian

have only the latter (vocalic tone)

2. Dynamic Stress and Vowel

Quantity

E.g. Russian, Bulgarian have

dynamic stress but no quantity;

Czech/Slovak have vowel quantity

but no phonemic stress.

Features that must be combined

1. Vocalic Tone and Vocalic

Quantity.

E.g. Slovene,

Serbian/Croatian/Bosnian have

both.

2. Vocalic Tone and Tonal Stress.

E.g. Slovene,

Serbian/Croatian/Bosnian

Features that may be combined or

not

1. Consonant Palatalization and

Dynamic Stress.

E.g. Russian, Bulgarian.

2. Consonant Palatalization and

Vowel Quantity.

E.g. Old Polish (before loss of

quantity)

3. Consonant Palatalization Without

Phonemic Stress or Vowel Quantity

E.g. Modern Polish.

4. Vowel Quantity Without

Phonemic Stress or Consonant

Palatalization

E.g. Czech/Slovak

30

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Ancient Indo-European Dialects: Proceedings of the Conference on Indo-European Linguistics Held at the University of California, Los Angeles April 25–27, 1963Von EverandAncient Indo-European Dialects: Proceedings of the Conference on Indo-European Linguistics Held at the University of California, Los Angeles April 25–27, 1963Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jasinskaja HIS SlavicDokument27 SeitenJasinskaja HIS SlavicJordiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13-18 PhoneticsDokument4 Seiten13-18 Phoneticszhannatagabergen2606Noch keine Bewertungen

- Vowel Reduction in RussianDokument66 SeitenVowel Reduction in RussianAlex CopeNoch keine Bewertungen

- пыл. (Russian scholars who belong to Moscow School claim that there are only 5 vowel phonemes in Russian, andDokument2 Seitenпыл. (Russian scholars who belong to Moscow School claim that there are only 5 vowel phonemes in Russian, andАнастасияNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabic Structure of English WordsDokument118 SeitenSyllabic Structure of English WordsКатерина ПарийNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assimilation in English and UzbekDokument24 SeitenAssimilation in English and UzbekAli AkbaralievNoch keine Bewertungen

- TitoDokument4 SeitenTitoMarcel PopescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barnes VR Final DraftDokument64 SeitenBarnes VR Final Draftyosep papuanus iyaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Independent WorkDokument5 SeitenIndependent WorkZhania NurbekovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phonological Analysis of LoanwordsDokument15 SeitenPhonological Analysis of LoanwordsMaha Mahmoud TahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 11Dokument28 SeitenLecture 11Aydana NurlanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabic Structure of English WordsDokument35 SeitenSyllabic Structure of English WordsBekmurod Ismatullayev100% (1)

- The Syllable Office PowerPointDokument25 SeitenThe Syllable Office PowerPointАнна ШаповаловаNoch keine Bewertungen

- Negation in HamletDokument9 SeitenNegation in HamletNehra NeLi TokićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 5Dokument10 SeitenLecture 5malikabahronqulovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eric Ed050612Dokument6 SeitenEric Ed050612Rui MachadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yugoslav Really President Yugoslav? Tito: UnclassifiedDokument4 SeitenYugoslav Really President Yugoslav? Tito: Unclassifiedporfirigenit1Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Munday - ch3.0-3.1 - Jakobson 19 SlidesDokument19 Seiten2016 Munday - ch3.0-3.1 - Jakobson 19 SlidesEvelina TutlyteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labov Language Variation and Change PDFDokument16 SeitenLabov Language Variation and Change PDFAlana LaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- CONTRIBUTION OF JACOBSON, CHOMSKY AND HALLE TOWARDS DISTINCTIVE FEATURES by DBDokument7 SeitenCONTRIBUTION OF JACOBSON, CHOMSKY AND HALLE TOWARDS DISTINCTIVE FEATURES by DBOnoriode PraiseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 3 Classification of English Speech SoundsDokument6 SeitenLecture 3 Classification of English Speech SoundsElesetera80% (5)

- Types, Degrees and Functions of Word StressDokument11 SeitenTypes, Degrees and Functions of Word StressDovranNoch keine Bewertungen

- 83 The Syntax of Slavic EditDokument18 Seiten83 The Syntax of Slavic EditHongweiZhangNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 семинарDokument4 Seiten12 семинарАнастасияNoch keine Bewertungen

- Correct Distinctive FeaturesDokument7 SeitenCorrect Distinctive Featuresanmar ahmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 SyllablesDokument38 Seiten5 SyllablesRio IrwansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defining The Linguistic AreaDokument23 SeitenDefining The Linguistic AreaAlfonso DíezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Keynotes About Phonetics LessonsDokument12 SeitenKeynotes About Phonetics Lessonsjean dupontNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labov: Language Variation and ChangeDokument16 SeitenLabov: Language Variation and Changedoky_lp100% (1)

- Odpowiedzi Do Typologii Test POPRAWKIDokument3 SeitenOdpowiedzi Do Typologii Test POPRAWKIolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of The Theoretical Basis To The Distinctive FeaturesDokument9 SeitenThe History of The Theoretical Basis To The Distinctive Featuresanmar ahmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Principles of Classification of English Vowels The Principles of Classification of English Consonants Word Stress in EnglishDokument6 SeitenThe Principles of Classification of English Vowels The Principles of Classification of English Consonants Word Stress in EnglishDress CodeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kurylowicz - On The Development of The Greek IntonationDokument12 SeitenKurylowicz - On The Development of The Greek IntonationdharmavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of Syllable Formation and Syllable DivisionDokument20 SeitenTheories of Syllable Formation and Syllable DivisionNina TsapovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sound Change: The Regular, The Unconscious, The Mysterious: W. Labov, U. of PennsylvaniaDokument78 SeitenSound Change: The Regular, The Unconscious, The Mysterious: W. Labov, U. of PennsylvaniaHuajian YeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabic Structure of English Words. Word Stress. PlanDokument14 SeitenSyllabic Structure of English Words. Word Stress. PlanOlena Olenych100% (1)

- Roman Jakobson Bilge MetintekinDokument4 SeitenRoman Jakobson Bilge MetintekinEASSANoch keine Bewertungen

- 674 Rule BorrowingDokument101 Seiten674 Rule Borrowing1uwantNoch keine Bewertungen

- AmerContribDickey67 86Dokument20 SeitenAmerContribDickey67 86meph666269Noch keine Bewertungen

- Obp 0207 05Dokument22 SeitenObp 0207 05Matthew DavisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabic ConsonantsDokument34 SeitenSyllabic ConsonantsMarcus SallerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary and Double Articulation: April 2011Dokument18 SeitenSecondary and Double Articulation: April 2011Point KillesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllable TypologyDokument17 SeitenSyllable TypologyGabriel Castro AlanizNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Phonological FeaturesDokument6 Seiten2 Phonological FeaturesAntonio IJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hazen Labov Chapter-LibreDokument16 SeitenHazen Labov Chapter-LibreprofessordeportuguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Phonetics and Phonology of Some Syllabic Consonants in Southern British EnglishDokument34 SeitenThe Phonetics and Phonology of Some Syllabic Consonants in Southern British EnglishkhalilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phonemes, Alophones 2Dokument2 SeitenPhonemes, Alophones 2MirnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 3 THE SYLLABLEDokument16 SeitenUnit 3 THE SYLLABLESeguraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Linguistics For Non-LinguistsDokument43 SeitenLinguistics For Non-Linguistslisbarbosa0% (1)

- SYLLABLE Learning MaterialDokument3 SeitenSYLLABLE Learning MaterialIrina MitkevichNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Phonetic and Phonology (Syllables)Dokument8 SeitenEnglish Phonetic and Phonology (Syllables)NurjannahMysweetheart100% (1)

- Distinctive FeaturesDokument23 SeitenDistinctive FeaturesRoxana LoredanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2Dokument2 SeitenChapter 2nataly cabralNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jakobson, RomanDokument3 SeitenJakobson, RomanDijana MiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Word Division and Syllabification in EnglishDokument8 SeitenWord Division and Syllabification in Englishamirzetz0% (1)

- Katia Kuza SEE 23-17 Compendium: Kingdoms and DialectsDokument4 SeitenKatia Kuza SEE 23-17 Compendium: Kingdoms and DialectsКатерина КузаNoch keine Bewertungen

- CBR PhonoDokument11 SeitenCBR PhonoDewi KhairunnisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isachenko A V Grammaticheskiy Stroy Russkogo Yazyka V Sopost Vol2Dokument288 SeitenIsachenko A V Grammaticheskiy Stroy Russkogo Yazyka V Sopost Vol2RonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Jakobson's 1948 System of Verb AccentuationDokument21 SeitenOn Jakobson's 1948 System of Verb AccentuationRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Introduction To William Pokhlebkin and His Contributions To Russian Culture by Ronald F FeldsteinDokument26 SeitenAn Introduction To William Pokhlebkin and His Contributions To Russian Culture by Ronald F Feldsteinmorefaya2006Noch keine Bewertungen

- On Binary Stress Oppositions and Distributions in RussianDokument18 SeitenOn Binary Stress Oppositions and Distributions in RussianRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isachenko A V Grammaticheskiy Stroy Russkogo Yazyka V Sopost Vol1Dokument148 SeitenIsachenko A V Grammaticheskiy Stroy Russkogo Yazyka V Sopost Vol1RonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jakobsonian Semantic Case Features in Relation To Russian Noun StressDokument9 SeitenJakobsonian Semantic Case Features in Relation To Russian Noun StressRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toporisic TrotDokument5 SeitenToporisic TrotRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nominal Prosodic Paradigms and Their Synchronic Reflexes in West SlavicDokument15 SeitenNominal Prosodic Paradigms and Their Synchronic Reflexes in West SlavicRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jakobson's Remarks On The Evolution of RussianDokument26 SeitenJakobson's Remarks On The Evolution of RussianRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

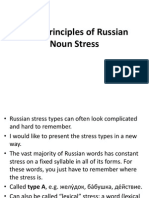

- Basic Principles of Russian Noun StressDokument21 SeitenBasic Principles of Russian Noun StressRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The System of Russian Verb Stress - (Latest Version)Dokument22 SeitenThe System of Russian Verb Stress - (Latest Version)RonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Principles of Russian Noun StressDokument21 SeitenBasic Principles of Russian Noun StressRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Protoslavic Prosodic Background of The Slovak Rhythmic LawDokument15 SeitenThe Protoslavic Prosodic Background of The Slovak Rhythmic LawRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basics of Russian Noun StressDokument21 SeitenBasics of Russian Noun StressRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prosodic Paradigms in West SlavicDokument12 SeitenProsodic Paradigms in West SlavicRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basics of Russian Noun StressDokument21 SeitenBasics of Russian Noun StressRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prosodic Paradigms in West SlavicDokument12 SeitenProsodic Paradigms in West SlavicRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reorganizing The Russian One-Stem Verb ClassesDokument3 SeitenReorganizing The Russian One-Stem Verb ClassesRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Russian Verbal Stress SystemDokument19 SeitenThe Russian Verbal Stress SystemRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review of A. A. Zaliznjak, Drevnerusskie Enklitiki.Dokument3 SeitenReview of A. A. Zaliznjak, Drevnerusskie Enklitiki.RonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- IWOBA7 Revised DraftDokument6 SeitenIWOBA7 Revised DraftRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Mobile Vowel Stress in Russian, As Influenced by Stem-Final ConsonantsDokument10 SeitenOn Mobile Vowel Stress in Russian, As Influenced by Stem-Final ConsonantsRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Introduction To Vil'iam Pokhlebkin and His Contributions To Russian CultureDokument17 SeitenAn Introduction To Vil'iam Pokhlebkin and His Contributions To Russian CultureRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regular and Deviant Patterns of Russian Nominal Stress and Their Relation To MarkednessDokument9 SeitenRegular and Deviant Patterns of Russian Nominal Stress and Their Relation To MarkednessRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nominal Prosodic Paradigms and Their Synchronic Reflexes in West SlavicDokument13 SeitenNominal Prosodic Paradigms and Their Synchronic Reflexes in West SlavicRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Polish Vowel Dispalatalization and Its EnvironmentDokument22 SeitenThe Polish Vowel Dispalatalization and Its EnvironmentRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Binary Feature Approach To Russian Nominal DeclensionDokument16 SeitenA Binary Feature Approach To Russian Nominal DeclensionRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Nature and Use of The Accentual Paradigm As Applied To RussianDokument9 SeitenThe Nature and Use of The Accentual Paradigm As Applied To RussianRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The Structural Meaning of The Dybo LawDokument10 SeitenOn The Structural Meaning of The Dybo LawRonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Right On! 2: ISBN 978-1-4715-5434-6Dokument23 SeitenRight On! 2: ISBN 978-1-4715-5434-6Nera Petronijevic100% (4)

- Notes - Light, Heavy & Irrelevant-1Dokument2 SeitenNotes - Light, Heavy & Irrelevant-1samiul bashirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phrasal Verbs ReadingDokument2 SeitenPhrasal Verbs ReadingBaruch P. BenítezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Erik Weihenmayer Is A Blind Mountain Climber (Noun) He Is A Blind Mountain Climber (Pronoun)Dokument4 SeitenErik Weihenmayer Is A Blind Mountain Climber (Noun) He Is A Blind Mountain Climber (Pronoun)Ãĥmăď ŚıľmľNoch keine Bewertungen

- AlaqaatDokument34 SeitenAlaqaatAlthaf FarookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Follow Directions Properly Follow Directions Properly : Edukasyon Sa Pagpapakatao MAPEH (Art)Dokument2 SeitenFollow Directions Properly Follow Directions Properly : Edukasyon Sa Pagpapakatao MAPEH (Art)Vilma TayumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class 13Dokument55 SeitenClass 13abcdNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Modal Defective VerbsDokument8 SeitenThe Modal Defective VerbsMarius AndreiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modals of Permision and AbilityDokument9 SeitenModals of Permision and AbilityEvalyn M. SalvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1) Active & PassiveDokument21 Seiten1) Active & PassiveMansoorHayatAwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- RoutledgeHandbooks 9780203880647 Chapter2Dokument50 SeitenRoutledgeHandbooks 9780203880647 Chapter2Vargas Hernandez SebastianNoch keine Bewertungen

- đồ án ngữ âm âm vịDokument2 Seitenđồ án ngữ âm âm vịkhánh hòa nguyễn thịNoch keine Bewertungen

- B2+ PPT With KeysDokument13 SeitenB2+ PPT With KeysSandra FiolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grammar Reference: Future SimpleDokument13 SeitenGrammar Reference: Future SimpleloredanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mapeh Least Learned Competencies 6Dokument2 SeitenMapeh Least Learned Competencies 6Anonymous QnNICuArTx90% (21)

- Q4 w1 g6 Edited VersionfnalDokument8 SeitenQ4 w1 g6 Edited VersionfnalVICKY HERMOSURANoch keine Bewertungen

- 3850h-Spanish II H-Teacher Guide U4Dokument2 Seiten3850h-Spanish II H-Teacher Guide U4api-259708434Noch keine Bewertungen

- Revision Worksheet: - (8 Grade - Level 4)Dokument2 SeitenRevision Worksheet: - (8 Grade - Level 4)CarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Business EnglishDokument128 SeitenGlobal Business EnglishAngela AlqueroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 9 TrabajoDokument2 SeitenUnit 9 TrabajoJose Doria CeronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Present Simple Grammar Grammar Guides - 110187Dokument2 SeitenPresent Simple Grammar Grammar Guides - 110187OLYANoch keine Bewertungen

- Ling 240: Language and MindDokument27 SeitenLing 240: Language and MindJaviera KaoriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Useful Phrases To Start A ConversationDokument22 SeitenUseful Phrases To Start A ConversationMeltem Akman100% (1)

- Unit 8: Grammar Focus 1-Relative Clauses of TimeDokument5 SeitenUnit 8: Grammar Focus 1-Relative Clauses of TimeAlkingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Punjabi Language and Major Punjabi DialectsDokument12 SeitenPunjabi Language and Major Punjabi DialectsPunjabiThinkTank100% (4)

- Ask Manu 08Dokument9 SeitenAsk Manu 08warsan1205Noch keine Bewertungen

- INGGRIsDokument4 SeitenINGGRIsMarisa LalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Welcome To The Basic Arabic CourseDokument6 SeitenWelcome To The Basic Arabic CourseRana EssamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Al-Kitaab Fii Taallum Al-Arabiyya Part oDokument3 SeitenAl-Kitaab Fii Taallum Al-Arabiyya Part oAlexandre DouradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Initial Consonant Blends Mix Pack 3Dokument8 SeitenInitial Consonant Blends Mix Pack 3Selam Amaniel100% (1)