Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Cooper National Interest PDF

Hochgeladen von

amiralaboraOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Cooper National Interest PDF

Hochgeladen von

amiralaboraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1

"Imperial Liberalism"

by Robert Cooper

1

,

The National Interest, n79, Spring 2005, pp. 25-34

It is difficult both to be good and to be powerful. This seems to be

the common view among statesmen, sages, poets and thinkers. A core

thesis among thinkers of the realist persuasion has been that in foreign

affairs, being good may in the end be bad for the people you serve, and

that moral ends may best be served by thinking in terms of power and

how it should be preserved instead of aiming to do directly what seems

morally good. This lesson is repeated in the works of Machiavelli,

Morgenthau, Kissinger and many others. Realism is about power, and

though barren and inadequate as a description of the way international

society functions, it is at least consistent. Likewise, liberal

internationalism, though its proponents have sometimes mistaken

aspiration for reality, is also consistent. But the attempt to combine the

two, as Charles Krauthammer does ("In Defense of Democratic Realism",

The National Interest, Fall 2004), presents difficulties in both theory and

practice.

One difficulty with democratic realism is the problem of power in a

democratic age. Once we knew what power looked like. It possessed a big

army and a big navy. You exercised power by beating someone elses

army and taking their land, their money, their women. Sometimes you

took over their territory and ruled it and them. In the last decades these

habits have died out among democracies: In an advanced industrial

society, land is more a burden than an asset. We have left behind the

static aristocratic society in which wealth appeared to be fixed, so that

you could become rich only by robbing others: Today peace and trade

provide a better return than war and looting. From the point of view of

wealth creation, war is a double negative. It destroys assets and does so

at great expense.

In a democratic age, ruling others is problematic. The notion that

all men are equal does not sit comfortably with empire. Nevertheless, the

idea of spreading the democratic system of government has great

attractions. We need an orderly world, and democracies are in the long

run more stable than dictatorships. Besides, like it or not, our

democratic values are universal. If all men are equal, then oppression

anywhere is offensive: it may not threaten our security, but it threatens

our self respect, for we are involved in mankind.

1

The author is Director-General for External and Politico-Military Affairs in the EU Council Secretariat.

He writes in a personal capacity.

2

The theory that democracies do not fight each other attracts

adherents as different as President Bush and Immanuel Kant. There are

also skeptics like Alexander Hamilton, who pointed out that Rome and

Athens were no less warlike for being republics. These were imperfect

democracies, it is true, but so in one way or another are all democracies.

Perhaps the fairest conclusion is that the no-war-between-democracies

thesis needs more time to establish itselfup to the present, the sample

of modern democracies has been too small. But for mature democracies

it does at least seem to have a plausible logic: Most people are cautious

about voting for policies that may involve them risking their lives. And

the evidence continues to accumulate.

The theory that well-governed societies will not produce terrorists

is manifestly not true: Timothy Mcveigh, British-born suicide bombers

and the Japanese terror cult Aum Shinrikyo are among the many

counter examples. But in a well-governed country there will be a better

chance of obtaining the support of the majority of the population against

the terrorists. Legitimacy is usually one of the keys to success.

Accountable police and intelligence services ought in the end to be more

efficient. But here also evidence is too thin for much certainly.

Nevertheless, a world of well-governed countries with accountable

executives, responsible assemblies and independent judiciaries seems

instinctively preferable to any of the alternatives. We feel more

comfortable with Japan mastering nuclear technology than with someone

like Saddam Hussein doing the same. Europe at the end of the 20

th

century is safer than Europe at its start; East Asia looks to be on the way

to being happier and safer than the Middle East.

The argument of the democratic realist thus has a compelling

simplicity and logic: Democracy is desirable, perhaps even imperative, for

our security, and America is now a dominant power in a way that is

without precedent. So American power should be used to promote

democracy. The problem with this argument is that American poweror

at least the dimension of power in which America is most evidently

dominantis military power and it is questionable how useful this is in

creating democracies. There are several systemic reasons for thinking it

may not be the best instrument for this goal.

Democratic systems and military systems are in many respects

opposites. Democracy is bottom up; military is top down. In military

systems hierarchy and rank are fundamental: in democracy the starting

point is that all men are equal. Democracy is about due process, rights,

limits to power; military systems work, necessarily, on the basis of

obedience to orders. These differences become even more marked when

3

an army has invaded someone elses country. An army gets its way by

violence and by the threat of violence, very different from the processes of

law that are embodied in democratic states. And whereas the principle of

equality before the law is basic to democracies there is nothing less equal

than the invading soldier and the local civilian. Thus although a foreign

country may invade with the best of intentions and may bring with it

professors of politics to explain democratic theory, what it does is

fundamentally undemocratic. Its words may say the right things but its

actions tell exactly the opposite story.

Behind this lies an even more fundamental question. How much

use is military power in a democratic age? What is the point of being the

solo superpower, the sole owner of the unipolar moment, if you cannot

maintain control of a single medium sized state, even over a medium

sized town? Of course the story in Iraq is far from over and the United

States, with Iraqi help, may well in the end establish order throughout

the country. Butand this is the pointif it does so it will be with Iraqi

help. No doubt even without Iraqi help the U.S. could take full control by

flooding the country with troops and using whatever degree of force was

required. This would be in the logic of military power, which after all is

about violence and threat. But it would not work. First of all it would not

work because the United States itself is democratic and its people would

not permit it: and secondly it would not work because Iraq, like every

other part of the world, is infused in a primitive way with a democratic

ideology. At the beginning of democracy is the idea of self determination,

the idea that you should be ruled by your own people and not by

foreigners. In the violent culture of the Middle East this may be

expressed in insurgency or support for insurgents; in Central Europe for

years it was expressed in sullen resistance, underground movements and

ironic humor. There too forty years of rule, through surrogates but

resting ultimately on military force, demonstrated the weakness of

military power in a democratic age.

As an authoritarian state the Soviet Union had less difficulty in

being brutal, though even its willingness to use force declined over the

forty year occupation. For America it is not so easy. The United States

may be the most powerful state since Rome but unlike the Roman

Empire it is democratic and its people will not tolerate Roman methods

(solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant)

2

. Military force still had its uses but

running or transforming other peoples countries is not one of them. To

see power only in military terms is a fundamental error in world politics.

2

They make a desert and they call it peace: Tacitus, Agricola

4

Charles Krauthammer might reply that the theory might not work

but the practice does. We have succeeded in the monumental task of

reconstructing Germany, Japan and South Korea. It is true that all of

these countries have had an American force presence over a long period

and also that during this period they have become stable democracies;

but the causation is not as simple as Krauthammer suggests. In fact the

three countries mentioned had very different histories and the United

States played a different role in each.

Germany under the Nazi Party was a tyranny and its overthrow

was a requirement for the reestablishment of democracy. Without the

American contribution in World War II this would probably never have

happened. The same is true of the Soviet contribution. With the

occupation, the difference between the American and Soviet approaches

became clearer: in the Western zonewhich was British and French as

well as American - democracy and the open society were refounded; in

the Soviet Zone a communist dictatorship. But in the West democratic

institutions were not established but reestablished. They were not new.

Different parts of Germany had different histories: the state of Baden had

universal suffrage from the early nineteenth century while Prussia was

still an autocracy. It is not clear whether the German state in the time of

the Kaiser should be called a democracy or not. Every one had a vote but

they were of unequal weight: by modern standards it would not qualify

as democratic; but that is also true of most other countries of the period.

The Weimar constitution, however, was undoubtedly democratic: for

example it gave votes to women a year before the 19

th

amendment did the

same in the United States and some decades before many other

European states.

U.S. policy in occupied Germany after World War II was not

directed primarily towards democratization. The Morgenthau Plan for the

deindustrialization of Germany was, fortunately, abandoned before the

occupation began. Nevertheless some of the thinking that inspired it

remained; JCS1067, the document that set out the main policies for the

U.S. occupation, states: Germany will not be occupied for the purpose of

liberation but as a defeated enemy nation.

3

Fraternization was

forbidden; agricultural reconstruction was to be encouraged and

American support for rebuilding German industry was prohibited. Lucius

Clay, the American Military Governor, wisely ignored both the spirit and

the letter of U.S. policy. His main motivation for seeking to transfer

authority to German politicians seems to have been the wish to end his

responsibility for tasks for which he felt thoroughly unprepared. His

3

Department of State: Documents on Germany

5

efforts to get guidance from the State Department on what exactly was

meant by either democracy or federalism were fruitless.

This did not matter much. Adenauer and Schumacher not only

knew more about Germany than did any of the occupation forces; they

also knew more about democracyhaving watched and suffered under

its decline in the 1930s. Perhaps Americans in general, coming from the

only state to have been born democratic are less aware of the difficulties

and travails of the process of becoming a democracy, Clay himself made

this point: I think we have a peculiar idea of our government being

perfect without knowing really and truly how it works.

4

The process of

creating a new German constitutionbased largely on Weimarwas

essentially a German one. The British had concluded that the best way to

deal with post war Germany would be to ensure that its government was

decentralized but it was Adenauers commitment to federalism that

mattered. In the case of Trade Union legislation, although it was the

British Military Government that first agreed to the creation of Unions

these were created on a German model, which learned some lessons from

the prewar period, rather than following British ideas. In education also

the Germans had their own ideas: the Minister for Culture in Lower

Saxony complained at receiving orders from foreigners when the best

vision of reform was German. In Bavaria they simply ignored allied

directives in this area. And so on.

The allies (not just America) played a part in reestablishing

German democracy. First they defeated Hitler, then they occupied

Germany in a largely benign fashion and took a benevolent attitude to

the rebirth of democratic institutionsboth quite different from what

happened in the Soviet zone. But the democratic development of

Germany after 1945 was first and foremost a German event. To claim

otherwise is not only to underestimate the Germans but also to

overestimate the degree to which an occupying military power can

control developments.

The constitution of post war West Germany was a German

product. The same cannot be said of the Japanese Constitution, which

was drafted by Americans working for the Supreme Commander for the

Allied Powers (SCAP), and - according to some Japanese - still reads like

a translation. Nevertheless the politicians who made it work were

authentically Japanese. In an analysis of the occupation period the

scholar Thomas A. Bisson, who himself had worked for SCAP, wrote:

4

Quoted in Niall Fergusson: Colossus, page 74, Allen Lane 2004

6

(T)he occupation authorities came prepared to play the role of

firm but benevolent guardians of a docile and oppressed people that

had no conception of the meaning much less the practice of

democratic rights and responsibilities. The general consensus of

opinion was that the majority of the Japanese would be meek and

apologetic and would willingly accept the tutelage of their

liberators. As it turned out however, the release of political

prisoners from jail, the granting of free speech, freedom of the

press, freedom of organization, and other rights produced a popular

movement that startled the occupation by its vigor and

independence, and by the far reaching character of its demands for

political and economic reform.

5

On the whole the reformers were disappointed by the extent to

which the old political and economic structures remained. The purge of

politicians and officials thought to be undesirable had limited effects.

The Japanese Government originally identified some 200,000 candidates

but by the time the occupation ended in 1952 only just over eight

thousand were still banned from office (including some communists who

had opposed Japanese militarism). Many of those banned, like Prime

Minister Hatoyama, subsequently returned. Two measures did have a

lasting impact: the dramatic land reform which changed the structure of

village societyand also helped ensure a permanent conservative

majority in the countryside; and the effective abolition of the armed

forces. This measure made a real difference since the army had been at

the root of the instability that brought down Japanese democracy in the

1930s. It is doubtful if the Japanese people would have done either of

these things on their owneven if they have been happy to accept the

results.

As in Germany, U.S. policies played a part in the restoration of

Japanese democracy; but anyone examining the whole period will reach

the conclusion that Japan was rebuilt as a successful democratic society

by the Japanese themselves. On reflection it is difficult to imagine

anything else. A few hundred foreign officials, most of them initially

ignorant of Japan, few of them speaking the language, were hardly likely

to bring about the complete transformation of Japanese society in a

seven year period.

The third example quoted by Krauthammer, Korea, is more

complicated. The United States never had the role or powers of an

occupying authority in Korea though it did have operational command

over the Republic of Korea's armed forces. How far the United States can

5

T A Bisson: Prospects for democracy in Japan. New York, Macmillan, 1949, p.74

7

claim credit for South Koreas democratic transformation over the forty

years from the end of the war is questionable. On the one side the State

Department and the U.S. Embassy in Seoul urged progress towards

democracy from time to time; and the United States probably saved Kim

Dae Jung from execution (and then gave him asylum in the United

States). On the other, the United States seems to have had little difficulty

in working closely with successive corrupt and authoritarian regimes,

and at critical moments did nothing to prevent the use of the military

against demonstrators

6

. Given the complexity of its security

responsibilities and the relationship between Washington and Seoul

there was perhaps little alternative. Nevertheless this does not look like

an active policy of promoting democracy. But while U.S. military power

may have done little directly for democracy in Korea, American influence

worked a slow and lasting transformation: the contact with American

society and government over the forty years following the end of the

Korean War played a positive, possibly a transforming role in Korean

thinking. And the transition to democracy is above all about changes in

ideas.

It should not be surprising in any of these cases that democracy

came from within rather than in the baggage train of a foreign army.

Democracy is rule by the people and who else but the people

themselves could be responsible for its establishment? You can use force

to impose your sonnovabitch but not to impose democratic politics.

This does not mean that foreigners and military power, have no

role at all. The first role that foreign armies may play is in the defeat of

an undemocratic regime. Few regimes survive a major military defeat.

What happens then depends on local circumstances. Often there will be

a reaction to the values of the regime which has lost the war and so

failed in its primary duty of providing security. The Prussian defeat of

Napoleon III brought the return to democracy in France. And when the

Third Republic was defeated it gave way, briefly, to Vichy amid disillusion

with democracy. The defeat of the Czar in World War I brought a

revolution which started with an incompetent attempt at democracy

and finished with Lenin. China in the twentieth century suffered

innumerable defeats at the hands of the Japanese and the West bringing

a series of revolutions that culminated in that of Mao Zedong. The defeat

of the Kaiserreich brought a period of democracy; but the incompleteness

6

General Magruder gave the Korean military permission to deploy troops to restore order when protests

broke out against Syngman Rhees fixing of elections but offered nothing more than verbal support when

the army chief of staff asked him to deploy American forces against Park Chung Hees coup overthrowing

a democratically elected government. In 1980 General Wickham agreed to release the Twentieth Division

from its duties in the DMZ. It was subsequently responsible for the deaths of perhaps a thousand

demonstrators in the Kwanju massacre.

8

of that defeat also gave legitimacy to the extreme right. After World War

II, Italy reacted against fascism and created a shaky but ultimately

enduring democracy. In Germany force was indeed necessary to establish

a new regime in Germany but that was in the East where the role of the

military was to suppress moves towards democracy. In Greece in 1974

the Colonels wisely did not wait to be defeated by Turkey but resigned

preemptively. In the same year, facing unwinnable wars in its colonies

the Portuguese army revolted and began a revolution against the right

wing authoritarian government. The result was very nearly a communist

government but in the end settled into a democracy. Thatchers victory

in the Falklands War brought the overthrow of the military regime and a

return to democracy in Argentina, an event that seemingly unleashed a

democratic domino effect in South America. Military defeat is not the

only kind of shock that can destabilize a regime in the Soviet Union it

was loss of empire; in Indonesia it a financial crisis but it remains

perhaps the worst shock a country can suffer and one of those most

likely to delegitimise a regime.

The second contribution that foreign forces can make is to bring

security. War is one of the great enemies of democracy. Control of the

military is fundamental to the rule of law. But in situations of national

emergency, under threat of attack or under popular enthusiasm for

righting the wrongs imposed by foreigners, democracy is at risk. It was

the dominance of the military in Japan in the 1930s that undermined its

struggling democracy. In Europe both fascism and communism came out

of war: communism through revolution brought by defeat. Fascisms

appeal in Germany was to those who believed Germany had been

betrayed rather than defeated; in Italy it was to former officers who felt

they had won Italys first victories only to surrender them to a cowardly

parliament and a peace-mongering church. In both countries the slogans

and imagery of the anti democratic movements were warlike (as was also

the case for communism). In Korea military coups have characteristically

been justified by the need for a strong government to deal with the

threat from the North. Perhaps, in this light, it could be argued that it is

not an accident that democracy has best developed and survived in

countries whose geography gave them some natural protection: Britain

and the United States relied on navieswhich are inherently less

destabilizing than armies: Scandinavia was remote; the Netherlands had

the option of defending itself by breaching the dikes.

Thus the United States made a vital contribution to democracy in

post-war Europe through the creation of NATO. By giving assurance of

security to the countries of Western Europe it removed the military from

9

domestic politics and herded them into a multilateral world. This was not

entirely successful in the case of Greece where the perceived threat from

Turkey remained a source of insecurity, and in Turkey where some

combination of external threat and the Kemalist legacy gave the army a

special position. But for the rest of Europe armies became increasingly

removed from politics

7

Later on a similar process was applied in Spain:

following the death of Franco Spain left fascism behind by entering into

the European Union while the Spanish army escaped its anti-democratic

past through integration into NATO. The importance of the external

environment, including its security dimension, was demonstrated again

in 1989 The revolutions of Central and Eastern Europe were not

democratic by chance. That most of the countries concerned had some,

albeit short, democratic experience probably helped; but what mattered

most was the security offered by the United States in the form of NATO

membership and the existence of a community of democracies in the

shape of the European Union (which also offered both incentives and

practical help with reform). As a result the outcome was very different

from that of the 1920s and 30s when the same countries were

sandwiched between communism and fascism and were threatened by

both.

In Japan when introducing the peace constitution General

MacArthur said: By this undertaking and commitment Japan

surrenders rights inherent in her own sovereignty and renders her future

security and very survival subject to the good faith and justice of the

peace-loving peoples of the world. Fortunately for Japan it has been the

United States rather than the peace-loving peoples of the world that has

safeguarded its security. Possibly Japanese democracy would have done

well without the Security Treaty but by taking responsibility for Japans

security the United States removed the military threat to democracy that

had been so destructive in the 1930s.

This raises the question why the transition to democracy was

so slow in the Republic of Korea. Unlike postwar Japan Korea's

external environment remained a negative factor, in spite of the US

security presence, resulting in a state that was too militarized to make it

easy for democratic aspirations to bear fruit, even when had it achieved

the high-income levels that seem normally to point towards democracy.

Yet without the secure environment provided by U.S. guarantees and

their visible embodiment in the U.S. force presence, the process might

have taken much longer.

7

The case of France is somewhat different but nevertheless illustrates some of these points: theloss of

Algeria brought France to the brink of a military coup. But even if this had succeeded and it did not -it is

difficult to imagine that it could have resulted in a lasting undemocratic regime.

10

The Korean experience, like that of many countries, illustrates

that democracy faces external threats as well as internal challenges.

The latter are of course essential. No matter how favourable the

external environment democracy will not take root unless some

basic compromises can be reached between different groups, classes

and ethnicities that establish the rules of the game. The losers in

elections must believe in the constitution sufficiently to accept defeatin

the confidence that they will get another chance later on to contest

elections. The winners must be sufficiently committed to the

constitution not to abuse it and use their power to oppress or

disadvantage the opposition. In achieving a settlement of these

fundamental questions outsiders cannot play much of a role.

Some of the enemies of democracydictators and their military

backingcan be defeated by armies. But not all. Sometimes the real

enemy is traditional society in its different forms; sometimes it is a

modern oligarchy bringing together politics, especially nationalist or

ethnic politics, and economic interest. The spread of ideas and the

spread of the market are the most important means to defeat these

(which is why modern oligarchs seek to control both). Assisting those

who are seeking fairer courts, freer media, genuine elections

8

, better

protection for human rights, better commercial law, may not produce

instant success but it must be worth trying. Scholarships, libraries and

other ways of spreading ideas may also have a part to play in the Middle

East, as they did in Korea. Slow, pedestrian, uncertain but no more

uncertain than the use of force. In the long run democracy succeeds

because of its success. Its product is the Mercedes Benz rather than the

Trabant, the PhD and foreign travel in South Korea rather than isolation

and starvation in the North. People want democracy because they want a

better life; consumerism is not beautiful but it too is an image of liberty.

Every country is different and there are as many routes to

democracy as there are countries. India took to it naturally; Pakistan has

struggled. Indonesia looks increasingly like a success story, against all

expectations. Thailand, Chile, Taiwan, South Africa, Spain all have

different stories. In many cases the position of the army has been a vital

factor. It may be that foreign forces will succeed in bringing democracy to

Iraq: it is always a mistake to underestimate either Americas will or its

capacity for getting things done - and the enthusiasm of most Iraqis for

elections is clear. But the choice will in the end be for the Iraqis and

8

It is striking how often the tribute despots pay to democracy in the form of elections can eventually

undermine them. It was elections that brought down Milosevic, not war or sanctions. As we have seen in

Ukraine the idea that you are being cheated in an election can mobilize popular feeling to an extent almost

nothing else can..

11

there is no way even the most powerful of foreign powers could guarantee

the outcome. We all hope for success but in historical terms it would be a

rare case, and it would be unwise to build too much on it. Indeed we

should be careful about using the threat of force to press for democratic

change: nothing is more likely to strengthen the tyrant and legitimize the

illegitimate than a foreign threat. No communist regime collapsed as a

result of outside pressure; internal change comes easier when people feel

more secure externally.

It is not a question of abandoning the Wilsonian vision of

encouraging the spread of democracy so much as being realistic

about what an outside actor can achieve. Foreigners, especially

foreign armies, are not equipped to broker domestic constitutional

settlements but they can create a positive external security

environment in which such a settlement will have more chance of

prospering. The inability to create an adequate security

environment in the 1920s and 1930s was a major reason for the

failure of the original Wilsonian package. At that time the failures

included the incomplete defeat of Germany, the defects in the

Versailles Treaty; the absence of the United States and Soviet

Russia from the League of Nations, the failure to put muscle behind

its somewhat cloudy ideas, and the cloudy nature of those ideas.

But the basic Wilsonian package was not wrong. Self-

determination, democracy and the institutionalization of international

security go well together. Self-determination is a precondition for

democracy: unless there is a sufficient sense of community, democracy

on the basis of majority voting will not work. Democracy in turn

contributes to peace. The idea that the peace will be kept by the force of

international public opinionon which ultimately the hopes for the

League restedmakes sense only if public opinion has a chance to make

itself heard, i.e. in a world of democracies. But democracy itself is most

likely to prosper in an international environment that creates trust

between states.

Trust between states, the classical realist may scoff, is

impossible. One of the (many) weaknesses of Wilsons rhetoric is that he

seemed to base his plans on the idea of a natural harmony of interests

among nations. Nothing of the sort exists. Nor, however, is there any

natural harmony of interests among men. The triumph of the rule of law

is that it manages these natural conflicts. It is the legal framework that

enables markets to channel greed into constructive economic activity. In

the end men discover that for all their natural conflicts they have a

common interest in upholding the law. But markets are not natural: they

are the outcome of man-made laws.

12

Nor is democracy the natural condition of mankind. It is simply

that experience has taught us that nothing else makes the rule of law

sustainable. The compromises necessary to make constitutions work are

the price we pay to channel ambition into constructive political activity.

Institutions exist to create trust, that indispensable element in human

society. The rule of law creates the trust that enables markets to

function. Democracy is a way of compensating for the fact that no one is

to be trusted with too much power for too long.

International institutions are needed for the same reasons: to

provide continuity and predictabilitythe next best thing to trust - in an

uncertain world. They are needed precisely because states, like men, are

not to be trusted. It would be logical for those who press the case for

domestic institutionsdemocracy and the market economy to want

institutions at the international level too.

We are now in a democratic era. This may be seen not just in the

growing number of democracies many of them rather shaky but also

in the homage paid to the idea of democracy by those like President

Mugabe who fix elections to give themselves a pretence of democratic

legitimacy; or by authoritarian countries like the DPRK who nonetheless

find it essential to include the D for Democratic in their name. The idea

is acknowledged even when the reality is denied.

This has consequences for the international system. The realist

world of rational policy making, equilibrium, alliances of convenience

and the balance of power, worked best when we were governed by

rational, oligarchsRichelieu, Pitt, Palmerston or Bismarck. Democratic

ideas mean that policy requires a moral basis. The idea of the dignity of

man will not go away; and policies have to be based on ideals and human

sympathy as well as on interest. In a democratic world, the use of force

becomes more difficult to handle. Wars need greater moral legitimacy

than in an autocratic age. To sell them a Roosevelt or a Reagan is

needed. And once started they are more difficult to end. Every war risks

becoming a crusade. This was not a problem in the cases of World War II

and the Cold War in both unconditional surrender was the only

acceptable outcome but it does not suit the conduct of lesser

campaigns. Democracy made it difficult for America either to prosecute

the Vietnam War with as much ruthlessness as the North did, or to cut

its losses and get out.

The balance of power, which calls for the application of power with

calculation and restraint, is no longer sustainable in a democratic age.

Nor is the exercise of hegemony by force which has been the other

13

source of stability in the international system. In a democracy

domination by the ruthless use of force ceases to be an option in the

international field as it is in the domestic - as Gandhi well understood

when he began the process of dismantling the British Empire.

Neither equilibrium nor domination works well in a democratic

age. And if democracies are inherently less bellicose, then basing the

international order on a system logically dependent on wars and force is

intellectually incoherent and practically mistaken. Nothing is left but to

manage international relations through institutionsas Woodrow Wilson

foresaw. Those that we have at the moment function poorlywhich is

hardly a surprise, given how short their history is. Even the most

competent, such as NATO and the EU come nowhere near matching the

national governments that make them up in either efficiency or

legitimacy (the two frequently go together). We have learned something

from past failures but there is much further to go.

Force remains indispensable in international affairs both because

we have not yet achieved the democratic dream; and even if we do it will

still be needed as the ultimate enforcer of law. In the meanwhile we need

force to protect ourselves and help create a favourable environment for

democracy. But as the world becomes more democratic, and so more

civilized force will be less visible and less prominent in international

relations.

We have chosen to be good rather than to be powerful. Torture is

unacceptable, not just because it is ineffective but because our system is

based on respect for individual people. Europeans talk of human rights

and the rule of law; Americans talk of freedom and democracy; but they

mean the same thing. For America the way to be good in a world of power

used to be to isolate itself. That is no longer possible. Instead it seeks to

remake the world in its own image. This is the European project also,

though on a more modest, regional basis. We are all Wilsonians now.

And we should understand that the true Wilsonian institutions are not

bodies like the UN but rather NATO and the European Union, embodying

the values of democracy and law.

Charles Krauthammer is right to want to accelerate the spread of

democracy, and he is probably right to be selective too - though in

practice what happens most often is that countries select themselves. It

would indeed be nice to remake the world; but some things are beyond

the control even of America. Democracy is one of them. Democracy

means rule by the people and no one else can make their choices for

them. The spread of the idea and the spread of the practice are

nevertheless impressive. There are many ways we can assist short of

14

employing force - using military power to provide security is one of them;

but in the end it is the force of the idea and the power of its practice that

conquers. Liberal imperialism may be an oxymoron but imperial

liberalism

9

is the reality of today.

9

The phrase, and the thought are not mine but belong to Professor Joachim Krause of Kiel University.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of ResentmentVon EverandIdentity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of ResentmentBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (65)

- The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save ItVon EverandThe People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save ItBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (33)

- Revolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of LawVon EverandRevolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Dictatorship - Crisis Government in the Modern DemocraciesVon EverandConstitutional Dictatorship - Crisis Government in the Modern DemocraciesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Realism Theory of International RelationsDokument5 SeitenRealism Theory of International Relationssharoona100% (1)

- IPHR Populism EssayDokument4 SeitenIPHR Populism EssayalannainsanityNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 A-6 Ordering Power - Dan SlaterDokument52 Seiten6 A-6 Ordering Power - Dan Slatervama3105Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Deep State: A History of Secret Agendas and Shadow GovernmentsVon EverandThe Deep State: A History of Secret Agendas and Shadow GovernmentsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Liberia Ok Physical Examination ReportcertDokument2 SeitenLiberia Ok Physical Examination ReportcertRicardo AquinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The American Tragedy ZDokument21 SeitenThe American Tragedy ZСергей КлевцовNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc Argument. I Hope You're Sufficiently IntimidatedDokument11 SeitenHoc Ergo Propter Hoc Argument. I Hope You're Sufficiently IntimidatedjpschubbsNoch keine Bewertungen

- DemocracyDokument6 SeitenDemocracyKrisna DNoch keine Bewertungen

- Road To DemocracyDokument19 SeitenRoad To DemocracyAlin MireaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ideology of Power FinalDokument8 SeitenIdeology of Power Finalapi-285705005Noch keine Bewertungen

- Power Rules: How Common Sense Can Rescue American Foreign PolicyVon EverandPower Rules: How Common Sense Can Rescue American Foreign PolicyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- Generic K AnswersDokument20 SeitenGeneric K AnswersjulianvgagnonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malik Thompson Trishia Briones ENGL 1302-261 19 April 2023Dokument8 SeitenMalik Thompson Trishia Briones ENGL 1302-261 19 April 2023api-608647073Noch keine Bewertungen

- MEARSHEIMER 2 NotesDokument6 SeitenMEARSHEIMER 2 NotesLavanya RaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentVon EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (17)

- Presidential Democracy in America Toward The Homogenized RegimeDokument16 SeitenPresidential Democracy in America Toward The Homogenized RegimeAndreea PopescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- DEMOCRATIC PARTY ELITISTS: Totalitarian Wolves In Sheep's ClothingVon EverandDEMOCRATIC PARTY ELITISTS: Totalitarian Wolves In Sheep's ClothingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malik Thompson Trishia Briones ENGL 1302-261 1 March 2023Dokument7 SeitenMalik Thompson Trishia Briones ENGL 1302-261 1 March 2023api-608647073Noch keine Bewertungen

- Malik Thompson Trishia Briones ENGL 1302-261 1 March 2023Dokument7 SeitenMalik Thompson Trishia Briones ENGL 1302-261 1 March 2023api-608647073Noch keine Bewertungen

- Parallels in Autocracy: How Nations Lose Their LibertyVon EverandParallels in Autocracy: How Nations Lose Their LibertyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Revenge of Power: How Autocrats Are Reinventing Politics for the 21st CenturyVon EverandThe Revenge of Power: How Autocrats Are Reinventing Politics for the 21st CenturyBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)

- Democracy Redefined: Stolen Elections And Perverted DemocracyVon EverandDemocracy Redefined: Stolen Elections And Perverted DemocracyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rueschemeyer Stephens StephensDokument6 SeitenRueschemeyer Stephens StephensEmma McCannNoch keine Bewertungen

- War Is Merely An IdeaDokument4 SeitenWar Is Merely An IdeaRVictoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- One World, Rival Theories - Jack SnyderDokument15 SeitenOne World, Rival Theories - Jack SnyderloodaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Concentration of Power: Institutionalization, Hierarchy & HegemonyVon EverandThe Concentration of Power: Institutionalization, Hierarchy & HegemonyNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Peace: Issues And: PerspectivesDokument22 SeitenWorld Peace: Issues And: PerspectivesArslan TanveerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Draft On The MonarchyDokument12 SeitenFinal Draft On The Monarchyapi-470535446Noch keine Bewertungen

- One World Rival TheoriesDokument12 SeitenOne World Rival TheorieshobbesianstudentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Politics Among NationsDokument7 SeitenPolitics Among NationstaukhirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Donald Trump and the Future of American Democracy: The Harbinger of a Storm?Von EverandDonald Trump and the Future of American Democracy: The Harbinger of a Storm?Noch keine Bewertungen

- ARCHIBUGI Can Democracy Be ExportedDokument17 SeitenARCHIBUGI Can Democracy Be ExportedJose Roberto RibeiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Modern State and Its Enemies: Democracy, Nationalism and AntisemitismVon EverandThe Modern State and Its Enemies: Democracy, Nationalism and AntisemitismNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Our Ancient Faith by Allen C. Guelzo: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American ExperimentVon EverandSummary of Our Ancient Faith by Allen C. Guelzo: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American ExperimentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democratic Tyranny and the Islamic ParadigmVon EverandDemocratic Tyranny and the Islamic ParadigmBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- The Future of MankindDokument3 SeitenThe Future of MankindHurmatMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy Is Everything?: Democracy, Militarism And World WarsVon EverandDemocracy Is Everything?: Democracy, Militarism And World WarsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crisang, Stephen Nikolai L. Legal Philosophy Mendoza, Nephtali R. 1-SDokument2 SeitenCrisang, Stephen Nikolai L. Legal Philosophy Mendoza, Nephtali R. 1-Snikol crisangNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Identity - Individual IntegrityDokument3 SeitenNational Identity - Individual IntegrityGabrielLopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Lonely SuperpowerDokument19 SeitenThe Lonely SuperpowerMatheus PimentelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democratic Socialism Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice Sage Reference Project (Forthcoming)Dokument11 SeitenDemocratic Socialism Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice Sage Reference Project (Forthcoming)Angelo MariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jack Snyder Rival TheoriesDokument12 SeitenJack Snyder Rival TheoriesTobi ErhardtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decline and Fall: The End of Empire and the Future of Democracy in 21st Century AmericaVon EverandDecline and Fall: The End of Empire and the Future of Democracy in 21st Century AmericaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ir AssingDokument5 SeitenIr AssingKainat KisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4.2 Types of Political Systems: Learning ObjectivesDokument9 Seiten4.2 Types of Political Systems: Learning ObjectivesDarry BlanciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impacts - Democracy Bad - Michigan 7 2022 BFHRDokument87 SeitenImpacts - Democracy Bad - Michigan 7 2022 BFHROwen ChenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Addicted To War PaperDokument3 SeitenAddicted To War PaperThomas SchjødtNoch keine Bewertungen

- International RelationsDokument5 SeitenInternational RelationsParsa MemarzadehNoch keine Bewertungen

- III.1. The Lack of Control Over The Matter of The NationDokument6 SeitenIII.1. The Lack of Control Over The Matter of The NationNhật MinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Concise History of American Politics: U S Political Science up to the 21St CenturyVon EverandA Concise History of American Politics: U S Political Science up to the 21St CenturyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toward Peace: Truth Is the Agent That Mediates HarmonyVon EverandToward Peace: Truth Is the Agent That Mediates HarmonyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Realism: Core AssumptionsDokument8 SeitenRealism: Core AssumptionsPARINoch keine Bewertungen

- The Bourgeoisie and Democracy: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives From Europe and Latin AmericaDokument20 SeitenThe Bourgeoisie and Democracy: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives From Europe and Latin AmericaJulia Perez ZorrillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rutherford County BallotsDokument8 SeitenRutherford County BallotsUSA TODAY NetworkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raw Jute Consumption Reconciliation For 2019 2020 Product Wise 07.9.2020Dokument34 SeitenRaw Jute Consumption Reconciliation For 2019 2020 Product Wise 07.9.2020Swastik MaheshwaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Watching The Watchers - Conducting Ethnographic Research On Covert Police Investigation in The UKDokument16 SeitenWatching The Watchers - Conducting Ethnographic Research On Covert Police Investigation in The UKIleana MarcuNoch keine Bewertungen

- FTP Chart1Dokument1 SeiteFTP Chart1api-286531621Noch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Advisory Service Integra GroupDokument24 SeitenCorporate Advisory Service Integra GroupJimmy InterfaxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chartering TermsDokument9 SeitenChartering TermsNeha KannojiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Overview of Entertainment Law in NigeDokument10 SeitenAn Overview of Entertainment Law in NigeCasmir OkereNoch keine Bewertungen

- M8 - Digital Commerce IDokument18 SeitenM8 - Digital Commerce IAnnisa PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adarsh Comp ConsDokument7 SeitenAdarsh Comp ConsAmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveDokument1 SeiteConstitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveKIM COLLEEN MIRABUENANoch keine Bewertungen

- Intolerance and Cultures of Reception in Imtiaz Dharker Ist DraftDokument13 SeitenIntolerance and Cultures of Reception in Imtiaz Dharker Ist Draftveera malleswariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intellectual CapitalDokument3 SeitenIntellectual CapitalMd Mehedi HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petron Vs CaberteDokument2 SeitenPetron Vs CabertejohneurickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Laws in IndiaDokument9 SeitenEnvironmental Laws in IndiaArjun RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Establishment of All India Muslim League: Background, History and ObjectivesDokument6 SeitenEstablishment of All India Muslim League: Background, History and ObjectivesZain AshfaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workbench Users Guide 15Dokument294 SeitenWorkbench Users Guide 15ppyim2012Noch keine Bewertungen

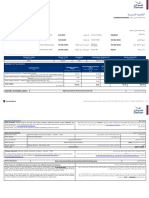

- ACCOUNT SUMMARY As of Jul 24, 2020Dokument4 SeitenACCOUNT SUMMARY As of Jul 24, 2020Mayara FazaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- MudarabaDokument18 SeitenMudarabaMuhammad Siddique BokhariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statement of Comprehensive IncomeDokument1 SeiteStatement of Comprehensive IncomeKent Raysil PamaongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Invoice Form 9606099Dokument4 SeitenInvoice Form 9606099Xx-DΞΛDSH0T-xXNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gillfab 1367B LaminateDokument2 SeitenGillfab 1367B LaminateLuis AbrilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax Challenges Arising From DigitalisationDokument250 SeitenTax Challenges Arising From DigitalisationlaisecaceoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oracle HCM Fusion Implementing On CloudDokument15 SeitenOracle HCM Fusion Implementing On CloudRaziuddin Ansari100% (2)

- St. Peter The Apostle Bulletin For The Week of 4-2-17Dokument8 SeitenSt. Peter The Apostle Bulletin For The Week of 4-2-17ElizabethAlejoSchoeterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Audit of InventoriesDokument4 SeitenAudit of InventoriesVel JuneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concepts of Constitution, Constitutional Law, and ConstitutionalismDokument6 SeitenConcepts of Constitution, Constitutional Law, and Constitutionalismكاشفة أنصاريNoch keine Bewertungen

- LOD For Personal LoanDokument4 SeitenLOD For Personal LoanAditya's TechNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freedom of SpeechDokument5 SeitenFreedom of SpeechDheeresh Kumar DwivediNoch keine Bewertungen

- DIGEST - UE Vs JaderDokument1 SeiteDIGEST - UE Vs JaderTea AnnNoch keine Bewertungen