Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Remedial Law Notes 2

Hochgeladen von

JoAnneGallowayOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Remedial Law Notes 2

Hochgeladen von

JoAnneGallowayCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Page 1 of 14

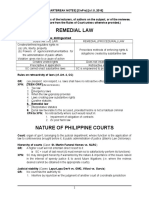

REMEDIAL LAW

by

Justice Zenaida T. Galapate-Laguilles

Expanded Certiorari Jurisdiction

Respondents raise the impropriety of the remedies of certiorari and

prohibition. They argue that public respondent was not exercising any judicial,

quasi-judicial or ministerial function in taking cognizance of the two

impeachment complaints as it was exercising a political act that is

discretionary in nature, and that its function is inquisitorial that is akin to a

preliminary investigation.

Francisco, Jr. v. House of Representatives characterizes the power of

judicial review as a duty which, as the expanded certiorari jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court reflects, includes the power to "determine whether or not there

has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction

on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government."

In the present case, petitioner invokes the Courts expanded certiorari

jurisdiction, using the special civil actions of certiorari and prohibition as

procedural vehicles. The Court finds it well-within its power to determine whether

public respondent committed a violation of the Constitution or gravely abused its

discretion in the exercise of its functions and prerogatives that could translate as

lack or excess of jurisdiction, which would require corrective measures from the

Court (Ma. Merceditas Gutierrez v. The House of Representatives

Committee on Justice, G.R. No. 193459, February 15, 2011).

Extrajudicial Foreclosure of Real Estate Mortgage

In extrajudicial foreclosure of real estate mortgage, the rule is upon the

expiration of the one year redemption period, it forecloses the obligors' right to

redeem and that the sale thereby becomes absolute. The time-honored precept

is that after the consolidation of titles in the buyers name, for failure of the

mortgagor to redeem, the writ of possession becomes a matter of right. Its

issuance to a purchaser in an extrajudicial foreclosure is merely a ministerial

function which cannot be enjoined or stayed, even by an action for annulment of

the mortgage or the foreclosure sale itself. The issuance of the final deed of sale,

therefore, is mere formality.

Thus, in the instant case, the failure of respondent (Atty. John V.

Aquino, Clerk of Court VI, Ex-Officio Sheriff) to issue the final deed of sale for

more than three (3) years clearly shows that he had been remiss in the

performance of his duties. The fact that a Writ of Mandamus was issued

likewise showed that the act of issuing the final deed of sale was ministerial,

therefore, respondent could not exercise discretion as to whether to issue the

same or not; it is not for him to decide the propriety or impropriety of the

issuance of the final deed of sale. More so, considering that no temporary

restraining order or injunctive order was issued to prevent the issuance of the

final deed of sale (Erdenberger v. Aquino, A.M. No. P-10-2739, August 24,

2011).

Page 2 of 14

Doctrine of Judicial Stability

The Doctrine of Judicial Stability or non-interference in the regular

orders or judgments of a co-equal court is an elementary principle in the

administration of justice: no court can interfere by injunction with the

judgments or orders of another court of concurrent jurisdiction having the

power to grant the relief sought by the injunction. The rationale for the rule is

founded on the concept of jurisdiction: a court that acquires jurisdiction over

the case and renders judgment therein has jurisdiction over its judgment, to

the exclusion of all other coordinate courts, for its execution and over all

its incidents, and to control, in furtherance of justice, the conduct of

ministerial officers acting in connection with this judgment.

Thus, we have repeatedly held that a case where an execution order has

been issued is considered as still pending, so that all the proceedings on the

execution are still proceedings in the suit. A court which issued a writ of

execution has the inherent power, for the advancement of justice, to correct

errors of its ministerial officers and to control its own processes. To hold

otherwise would be to divide the jurisdiction of the appropriate forum in the

resolution of incidents arising in execution proceedings. Splitting of jurisdiction

is obnoxious to the orderly administration of justice.

In Heirs of Simeon Piedad v. Estrera, the Court penalized two judges for

issuing a TRO against the execution of a demolition order issued by another co-

equal court. The Court stressed that when the respondents-judges acted on

the application for the issuance of a TRO, they were aware that they were

acting on matters pertaining to a co-equal court, namely, Branch 9 of the Cebu

City RTC, which was already exercising jurisdiction over the subject matter in

Civil Case No. 435-T. Nonetheless, respondent-judges still opted to interfere

with the order of a co-equal and coordinate court of concurrent jurisdiction, in

blatant disregard of the doctrine of judicial stability, a well-established axiom

in adjective law (Cabili v. Judge Balindong, A.M. No. RTJ-10-2225, September

6, 2011).

Forcible Entry/Unlawful Detainer

While the court in an ejectment case may delve on the issue of ownership

or possession de jure solely for the purpose of resolving the issue of

possession de facto, it has no jurisdiction to settle with finality the issue of

ownership and any pronouncement made by it on the question of ownership is

provisional in nature. A judgment in a forcible entry or detainer case disposes

of no other issue than possession and establishes only who has the right of

possession, but by no means constitutes a bar to an action for determination of

who has the right or title of ownership. We have held that although it was

proper for the RTC, on appeal in the ejectment suit, to delve on the issue of

ownership and receive evidence on possession de jure, it cannot adjudicate

with semblance of finality the ownership of the property to either party by

ordering the cancellation of the TCT (Spouses Manila v. Spouses Manzo, G.R.

No. 163602, September 7, 2011).

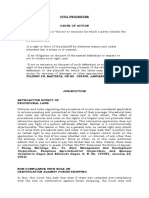

Payment of docket fee

Page 3 of 14

Payment of docket and other fees within the period for taking an appeal

is mandatory for the perfection of the appeal. Otherwise, the right to appeal is

lost. This is so because a court acquires jurisdiction over the subject matter of the

action only upon the payment of the correct amount of docket fees regardless of

the actual date of filing of the case in court. The payment of appellate docket

fees is not a mere technicality of law or procedure. It is an essential

requirement, without which the decision or final order appealed from becomes

final and executory as if no appeal was filed (D. M. Wenceslao and Associates,

Inc. v. City of Paraaque, G.R. No. 170728, August 31, 2011).

The filing of the complaint or other initiatory pleading and the payment

of the prescribed docket fee are the acts that vest a trial court with jurisdiction

over the claim. In an action where the reliefs sought are purely for sums of

money and damages, the docket fees are assessed on the basis of the aggregate

amount being claimed. Ideally, therefore, the complaint or similar pleading

must specify the sums of money to be recovered and the damages being sought

in order that the clerk of court may be put in a position to compute the correct

amount of docket fees.

If the amount of docket fees paid is insufficient in relation to the

amounts being sought, the clerk of court or his duly authorized deputy has the

responsibility of making a deficiency assessment, and the plaintiff will be

required to pay the deficiency. The non-specification of the amounts of damages

does not immediately divest the trial court of its jurisdiction over the case,

provided there is no bad faith or intent to defraud the Government on the part of

the plaintiff.

The prevailing rule is that if the correct amount of docket fees are not

paid at the time of filing, the trial court still acquires jurisdiction upon full

payment of the fees within a reasonable time as the court may grant, barring

prescription. The prescriptive period that bars the payment of the docket fees

refers to the period in which a specific action must be filed, so that in every

case the docket fees must be paid before the lapse of the prescriptive period, as

provided in the applicable laws, particularly Chapter 3, Title V, Book III, of

the Civil Code, the principal law on prescription of actions (Fedman

Development Corporation v. Agcaoili, G.R. No. 165025, August 31, 2011).

Criminal Contempt versus Civil Contempt

Proceedings for contempt are sui generis, in nature criminal, but may be

resorted to in civil as well as criminal actions, and independently of any action.

They are of two classes, the criminal or punitive, and the civil or

remedial. A criminal contempt consists in conduct that is directed against the

authority and dignity of a court or of a judge acting judicially, as in unlawfully

assailing or discrediting the authority and dignity of the court or judge, or in

doing a duly forbidden act. A civil contempt consists in the failure to do

something ordered to be done by a court or judge in a civil case for the benefit

of the opposing party therein. It is at times difficult to determine whether the

proceedings are civil or criminal. In general, the character of the contempt of

whether it is criminal or civil is determined by the nature of the contempt

involved, regardless of the cause in which the contempt arose, and by the relief

sought or dominant purpose.

The proceedings are to be regarded as criminal when the purpose is

primarily punishment, and civil when the purpose is primarily compensatory or

remedial.Where the dominant purpose is to enforce compliance with an order

of a court for the benefit of a party in whose favor the order runs, the contempt

Page 4 of 14

is civil; where the dominant purpose is to vindicate the dignity and authority of

the court, and to protect the interests of the general public, the contempt is

criminal. Indeed, the criminal proceedings vindicate the dignity of the courts,

but the civil proceedings protect, preserve, and enforce the rights of private

parties and compel obedience to orders, judgments and decrees made to

enforce such rights (Lorenzo Shipping Corporation v. Distribution

Management Association of the Philippines, G.R. No. 155849, August 31,

2011)

Judgment on the Pleadings versus Summary Judgment

What distinguishes a judgment on the pleadings from a summary

judgment is the presence of issues in the Answer to the Complaint. When the

Answer fails to tender any issue, that is, if it does not deny the material

allegations in the complaint or admits said material allegations of the adverse

partys pleadings by admitting the truthfulness thereof and/or omitting to deal

with them at all, a judgment on the pleadings is appropriate. On the other

hand, when the Answer specifically denies the material averments of the

complaint or asserts affirmative defenses, or in other words raises an issue, a

summary judgment is proper provided that the issue raised is not genuine. A

genuine issue means an issue of fact which calls for the presentation of

evidence, as distinguished from an issue which is fictitious or contrived or

which does not constitute a genuine issue for trial (Basbas v. Sayson, G.R.

No. 172660, August 24, 2011).

EVIDENCE

PEOPLE V. HUBERT WEBB, G.R. NO. 176864, DECEMBER 14, 2010

DNA Evidence

Webb claims, citing Brady v. Maryland, that he is entitled to outright

acquittal on the ground of violation of his right to due process given the States

failure to produce on order of the Court either by negligence or willful

suppression the semen specimen taken from Carmela.

The medical evidence clearly established that Carmela was raped and,

consistent with this, semen specimen was found in her. It is true that Alfaro

identified Webb in her testimony as Carmelas rapist and killer but serious

questions had been raised about her credibility. At the very least, there exists a

possibility that Alfaro had lied. On the other hand, the semen specimen taken

from Carmela cannot possibly lie. It cannot be coached or allured by a promise

of reward or financial support. No two persons have the same DNA fingerprint,

with the exception of identical twins. If, on examination, the DNA of the subject

specimen does not belong to Webb, then he did not rape Carmela. It is that

simple. Thus, the Court would have been able to determine that Alfaro

committed perjury in saying that he did.

Page 5 of 14

Still, Webb is not entitled to acquittal for the failure of the State to

produce the semen specimen at this late stage. For one thing, the ruling in

Brady v. Maryland that he cites has long be overtaken by the decision in

Arizona v. Youngblood, where the U.S. Supreme Court held that due process

does not require the State to preserve the semen specimen although it might be

useful to the accused unless the latter is able to show bad faith on the part of

the prosecution or the police. Here, the State presented a medical expert who

testified on the existence of the specimen and Webb in fact sought to have the

same subjected to DNA test.

For, another, when Webb raised the DNA issue, the rule governing DNA

evidence did not yet exist, the country did not yet have the technology for

conducting the test, and no Philippine precedent had as yet recognized its

admissibility as evidence. Consequently, the idea of keeping the specimen

secure even after the trial court rejected the motion for DNA testing did not

come up. Indeed, neither Webb nor his co-accused brought up the matter of

preserving the specimen in the meantime.

Parenthetically, after the trial court denied Webbs application for DNA

testing, he allowed the proceeding to move on when he had on at least two

occasions gone up to the Court of Appeals or the Supreme Court to challenge

alleged arbitrary actions taken against him and the other accused. They raised

the DNA issue before the Court of Appeals but merely as an error committed by

the trial court in rendering its decision in the case. None of the accused filed a

motion with the appeals court to have the DNA test done pending adjudication

of their appeal. This, even when the Supreme Court had in the meantime

passed the rules allowing such test. Considering the accuseds lack of interest

in having such test done, the State cannot be deemed put on reasonable notice

that it would be required to produce the semen specimen at some future time.

xxx xxx xxx

The Court of Appeals rejected the evidence of Webbs passport since he

did not leave the original to be attached to the record. But, while the best

evidence of a document is the original, this means that the same is

exhibited in court for the adverse party to examine and for the judge to

see. As Court of Appeals Justice Tagle said in his dissent, the practice when a

party does not want to leave an important document with the trial court is to

have a photocopy of it marked as exhibit and stipulated among the parties as a

faithful reproduction of the original. Stipulations in the course of trial are

binding on the parties and on the court.

The U.S. Immigration certification and the computer print-out of Webbs

arrival in and departure from that country were authenticated by no less than

the Office of the U.S. Attorney General and the State Department. Still the

Court of Appeals refused to accept these documents for the reason that Webb

failed to present in court the immigration official who prepared the same. But

this was unnecessary. Webbs passport is a document issued by the

Philippine government, which under international practice, is the official

record of travels of the citizen to whom it is issued. The entries in that

passport are presumed true.

The U.S. Immigration certification and computer print-out, the official

certifications of which have been authenticated by the Philippine Department

of Foreign Affairs, merely validated the arrival and departure stamps of the U.S.

Page 6 of 14

Immigration office on Webbs passport. They have the same evidentiary

value. The officers who issued these certifications need not be presented

in court to testify on them. Their trustworthiness arises from the sense

of official duty and the penalty attached to a breached duty, in the

routine and disinterested origin of such statement and in the publicity of

the record.

The trial court and the Court of Appeals expressed marked cynicism over

the accuracy of travel documents like the passport as well as the domestic and

foreign records of departures and arrivals from airports. They claim that it

would not have been impossible for Webb to secretly return to the Philippines

after he supposedly left it on March 9, 1991, commit the crime, go back to the

U.S., and openly return to the Philippines again on October 26, 1992. Travel

between the U.S. and the Philippines, said the lower courts took only about

twelve to fourteen hours.

If the Court were to subscribe to this extremely skeptical view, it might

as well tear the rules of evidence out of the law books and regard suspicions,

surmises, or speculations as reasons for impeaching evidence. It is not that

official records, which carry the presumption of truth of what they state,

are immune to attack. They are not. That presumption can be overcome

by evidence. Here, however, the prosecution did not bother to present evidence

to impeach the entries in Webbs passport and the certifications of the Philippine

and U.S. immigration services regarding his travel to the U.S. and back. The

prosecutions rebuttal evidence is the fear of the unknown that it planted in the

lower courts minds.

Marital Privilege Rule

The marital privilege rule, being a rule of evidence, may be waived by

failure of the claimant to object timely to its presentation or by any conduct

that may be construed as implied consent (Judge Lacurom v. Jacoba, A.C.

No. 5921, March 10, 2006).

Section 24 of Rule 130 draws the types of disqualification by reason of

privileged communication, to wit: (a) communication between husband and

wife; (b) communication between attorney and client; (c) communication

between physician and patient; (d) communication between priest and

penitent; and (e) public officers and public interest. There are, however,

other privileged matters that are not mentioned by Rule 130. Among them

are the following: (a) editors may not be compelled to disclose the source of

published news; (b) voters may not be compelled to disclose for whom they

voted; (c) trade secrets; (d) information contained in tax census returns; and (d)

bank deposits (Air Philippines Corporation v. Pennswell, Inc., G.R. No.

172835, December 13, 2007).

Circumstantial Evidence

Circumstantial evidence, also known as indirect or presumptive

evidence, refers to proof of collateral facts and circumstances whence the

existence of the main fact may be inferred according to reason and common

experience. Circumstantial evidence is sufficient to sustain conviction if (a)

there is more than one circumstance; (b) the facts from which the inferences

are derived are proven; (c) the combination of all circumstances is such as to

Page 7 of 14

produce a conviction beyond reasonable doubt. A judgment of conviction based

on circumstantial evidence can be sustained when the circumstances proved

form an unbroken chain that results in a fair and reasonable conclusion

pointing to the accused, to the exclusion of all others, as the perpetrator.

A medical examination and a medical certificate are merely corroborative

and are not indispensable to the prosecution of a rape case (People v. Gallo,

et al., G.R. No. 181902, August 31, 2011).

Tender of excluded evidence

At any rate, even assuming that the trial court erroneously rejected the

introduction as evidence of the CA Decision, petitioner is not left without legal

recourse. Petitioner could have availed of the remedy provided in Section 40, Rule

132 of the Rules of Court which provides:

Section 40. Tender of excluded evidence. If documents or things

offered in evidence are excluded by the court, the offeror may have the

same attached to or made part of the record. If the evidence excluded is

oral, the offeror may state for the record the name and other personal

circumstances of the witness and the substance of the proposed

testimony.

As observed by the appellate court, if the petitioner is keen on having the RTC

admit the CAs Decision for whatever it may be worth, he could have included the

same in his offer of exhibits. If an exhibit sought to be presented in evidence is

rejected, the party producing it should ask the courts permission to have the exhibit

attached to the record.

As things stand, the CA Decision does not form part of the records of the case,

thus it has no probative weight. Any evidence that a party desires to submit for the

consideration of the court must be formally offered by him otherwise it is excluded

and rejected and cannot even be taken cognizance of on appeal. The rules of

procedure and jurisprudence do not sanction the grant of evidentiary value to

evidence which was not formally offered (Catacutan v. People, G.R. No. 175991,

August 31, 2011).

SPECIAL PROCEEDINGS

Property Rights Not Protected by the Writ of Amparo

A persons right to be restituted of his property is already subsumed

under the general rubric of property rightswhich are no longer protected by

the writ of amparo. Section 1 of the Amparo Rule, which defines the scope and

extent of the writ, clearly excludes the protection of property rights (In the

Matter of the Petition for the Writ of Amparo and the Writ of Habeas Data

in Favor of Melissa C. Roxas, G.R. No. 189155, September 7, 2010).

At the outset, we agree with the complainant that the respondent judge

erred in issuing the Writ of Amparo in Tanmalacks favor. Had he read Section

1 of the Rule on the Writ of Amparo more closely, the respondent judge would

have realized that the writ, in its present form, only applies to extralegal

killings and enforced disappearances or threats thereof. The present case

Page 8 of 14

involves concerns that are purely property and commercial in nature

concerns that we have previously ruled are not covered by the Writ of Amparo.

In Tapuz v. Del Rosario, we held:

To start off with the basics, the writ of amparo was originally conceived

as a response to the extraordinary rise in the number of killings and enforced

disappearances, and to the perceived lack of available and effective remedies to

address these extraordinary concerns. It is intended to address violations of or

threats to the rights to life, liberty or security, as an extraordinary and

independent remedy beyond those available under the prevailing Rules, or as a

remedy supplemental to these Rules. What it is not, is a writ to protect

concerns that are purely property or commercial. Neither is it a writ that

we shall issue on amorphous and uncertain grounds (Salcedo v. Bollozos,

A.M. NO. RTJ-10-2236, July 5, 2010).

Order of Priority of Who May File a Writ of Amparo

Petitioners point out that the parents of Sherlyn and Karen do not have

the requisite standing to file the amparo petition on behalf of Merino. They call

attention to the fact that in the amparo petition, the parents of Sherlyn and

Karen merely indicated that they were concerned with Manuel Merino as

basis for filing the petition on his behalf.

Section 2 of the Rule on the Writ of Amparo provides:

The petition may be filed by the aggrieved party or by any

qualified person or entity in the following order:

(a) Any member of the immediate family, namely: the

spouse, children and parents of the aggrieved party;

(b) Any ascendant, descendant or collateral relative of the

aggrieved party within the fourth civil degree of consanguinity or

affinity, in default of those mentioned in the preceding paragraph;

or

(c) Any concerned citizen, organization, association or

institution, if there is no known member of the immediate

family or relative of the aggrieved party.

Indeed, the parents of Sherlyn and Karen failed to allege that there were

no known members of the immediate family or relatives of Merino. The

exclusive and successive order mandated by the above-quoted provision

must be followed. The order of priority is not without reasonto prevent

the indiscriminate and groundless filing of petitions for amparo which

may even prejudice the right to life, liberty or security of the aggrieved

party.

The Court notes that the parents of Sherlyn and Karen also filed the

petition for habeas corpus on Merinos behalf. No objection was raised therein

for, in a habeas corpusproceeding, any person may apply for the writ on behalf

of the aggrieved party.

It is thus only with respect to the amparo petition that the parents of

Sherlyn and Karen are precluded from filing the application on Merinos behalf

Page 9 of 14

as they are not authorized parties under the Rule (Boac v. Cadapan, G.R. Nos.

184461-62 , May 31, 2011).

Command Responsibility in Amparo Proceedings

It must be stated at the outset that the use by the petitioner of

the doctrine of command responsibility as the justification in impleading the

public respondents (public officials occupying the uppermost echelons of the

military and police hierarchy) in her amparo petition, is legally inaccurate, if

not incorrect. The doctrine of command responsibility is a rule of

substantive law that establishes liability and, by this account, cannot be a

proper legal basis to implead a party-respondent in an amparo petition.

The case of Rubrico v. Arroyo, which was the first to examine command

responsibility in the context of an amparo proceeding, observed that the

doctrine is used to pinpoint liability. Rubrico notes that:

The evolution of the command responsibility doctrine finds its

context in the development of laws of war and armed combats.

According to Fr. Bernas, "command responsibility," in its simplest

terms, means the "responsibility of commanders for crimes

committed by subordinate members of the armed forces or other

persons subject to their control in international wars or domestic

conflict." In this sense, command responsibility is properly a form

of criminal complicity. The Hague Conventions of 1907 adopted the

doctrine of command responsibility, foreshadowing the present-day

precept of holding a superior accountable for the atrocities

committed by his subordinates should he be remiss in his duty of

control over them. As then formulated, command responsibility is

"an omission mode of individual criminal liability," whereby the

superior is made responsible for crimes committed by his

subordinates for failing to prevent or punish the perpetrators (as

opposed to crimes he ordered). (Emphasis in the orginal,

underscoring supplied)

Since the application of command responsibility presupposes an

imputation of individual liability, it is more aptly invoked in a full-blown

criminalor administrative case rather than in a

summary amparo proceeding. The obvious reason lies in the nature of the

writ itself:

The writ of amparo is a protective remedy aimed at providing judicial

relief consisting of the appropriate remedial measures and directives that may

be crafted by the court, in order to address specific violations or threats of

violation of the constitutional rights to life, liberty or security. While the

principal objective of its proceedings is the initial determination of

whether an enforced disappearance, extralegal killing or threats thereof

had transpiredthe writ does not, by so doing, fix liability for such

disappearance, killing or threats, whether that may be criminal, civil or

administrative under the applicable substantive law. The rationale

underpinning this peculiar nature of an amparo writ has been, in turn, clearly

set forth in the landmark case of The Secretary of National Defense v.

Manalo:

Page 10 of 14

x x x The remedy provides rapid judicial relief as it partakes of a

summary proceeding that requires only substantial evidence to

make the appropriate reliefs available to the petitioner; it is not an

action to determine criminal guilt requiring proof beyond

reasonable doubt, or liability for damages requiring

preponderance of evidence, or administrative responsibility

requiring substantial evidence that will require full and

exhaustive proceedings.

It must be clarified, however, that the inapplicability of the doctrine of

command responsibility in an amparo proceeding does not, by any measure,

preclude impleading military or police commanders on the ground that the

complained acts in the petition were committed with their direct or indirect

acquiescence. In which case, commanders may be impleadednot actually on

the basis of command responsibilitybut rather on the ground of

their responsibility, or at least accountability. In Razon v. Tagitis, the

distinct, but interrelated concepts of responsibility and accountability were

given special and unique significations in relation to an amparo proceeding, to

wit:

x x x Responsibility refers to the extent the actors have been established

by substantial evidence to have participated in whatever way, by action or

omission, in an enforced disappearance, as a measure of the remedies this

Court shall craft, among them, the directive to file the appropriate criminal and

civil cases against the responsible parties in the proper

courts. Accountability, on the other hand, refers to the measure of remedies

that should be addressed to those who exhibited involvement in the enforced

disappearance without bringing the level of their complicity to the level of

responsibility defined above; or who are imputed with knowledge relating to the

enforced disappearance and who carry the burden of disclosure; or those who

carry, but have failed to discharge, the burden of extraordinary diligence in the

investigation of the enforced disappearance (In the Matter of the Petition for

the Writ of Amparo and the Writ of Habeas Data in Favor of Melissa C.

Roxas, G.R. No. 189155, September 7, 2010).

Scope of the Writ of Amparo

The Rule on the Writ of Amparo provides:

SECTION 1. Petition. The petition for a writ of amparo is a

remedy available to any person whose right to life, liberty and

security is violated or threatened with violation by an unlawful act

or omission of a public official or employee, or of a private

individual or entity.

The writ shall cover extralegal killings and enforced

disappearances or threats thereof. (Emphasis supplied.)

The threatened demolition of a dwelling by virtue of a final judgment of

the court, which in this case was affirmed with finality by this Court in G.R.

Nos. 177448, 180768, 177701, 177038, is not included among the

enumeration of rights as stated in the above-quoted Section 1 for which the

remedy of a writ of amparo is made available. Their claim to their dwelling,

Page 11 of 14

assuming they still have any despite the final and executory judgment adverse

to them, does not constitute right to life, liberty and security. There is,

therefore, no legal basis for the issuance of the writ of amparo (Canlas v.

NAPICO Homeowners Association, G.R. No. 182795, June 5, 2008).

Writ of Habeas Data

The writ of habeas data was conceptualized as a judicial remedy

enforcing the right to privacy, most especially the right to informational privacy

of individuals. The writ operates to protect a persons right to control

information regarding himself, particularly in the instances where such

information is being collected through unlawful means in order to achieve

unlawful ends.

Needless to state, an indispensable requirement before the privilege of

the writ may be extended is the showing, at least by substantial evidence, of an

actual or threatened violation of the right to privacy in life, liberty or security of

the victim (In the Matter of the Petition for the Writ of Amparo and the

Writ of Habeas Data in Favor of Melissa C. Roxas, G.R. No. 189155,

September 7, 2010).

Rules of Civil Actions Applicable in Special Proceedings

Petitioner's contention that rules in ordinary actions are only

supplementary to rules in special proceedings is not entirely correct.

Section 2, Rule 72, Part II of the same Rules of Court provides:

Sec. 2. Applicability of rules of Civil Actions. - In the

absence of special provisions, the rules provided for in ordinary

actions shall be, as far as practicable, applicable in special

proceedings.

Stated differently, special provisions under Part II of the Rules of Court

govern special proceedings; but in the absence of special provisions, the rules

provided for in Part I of the Rules governing ordinary civil actions shall be

applicable to special proceedings, as far as practicable.

The word practicable is defined as: possible to practice or perform;

capable of being put into practice, done or accomplished. This means that in the

absence of special provisions, rules in ordinary actions may be applied in

special proceedings as much as possible and where doing so would not pose an

obstacle to said proceedings. Nowhere in the Rules of Court does it

categorically say that rules in ordinary actions are inapplicable or

merely suppletory to special proceedings. Provisions of the Rules of Court

requiring a certification of non-forum shopping for complaints and initiatory

pleadings, a written explanation for non-personal service and filing, and the

payment of filing fees for money claims against an estate would not in any way

obstruct probate proceedings, thus, they are applicable to special proceedings

such as the settlement of the estate of a deceased person as in the present case

(Sheker v. Estate of Alice O. Sheker, G.R. No. 157912, December 13,

2007).

Page 12 of 14

Jurisdiction of the Trial Court as a Probate or an Intestate Court

The general rule is that the jurisdiction of the trial court, either as a

probate or an intestate court, relates only to matters having to do with the

probate of the will and/or settlement of the estate of deceased persons, but does

not extend to the determination of questions of ownership that arise during the

proceedings. The patent rationale for this rule is that such court merely

exercises special and limited jurisdiction. As held in several cases, a probate

court or one in charge of estate proceedings, whether testate or intestate,

cannot adjudicate or determine title to properties claimed to be a part of the

estate and which are claimed to belong to outside parties, not by virtue of any

right of inheritance from the deceased but by title adverse to that of the

deceased and his estate. All that the said court could do as regards said

properties is to determine whether or not they should be included in the

inventory of properties to be administered by the administrator. If there is no

dispute, there poses no problem, but if there is, then the parties, the

administrator, and the opposing parties have to resort to an ordinary action

before a court exercising general jurisdiction for a final determination of the

conflicting claims of title.

However, this general rule is subject to exceptions as justified by

expediency and convenience.

First, the probate court may provisionally pass upon in an intestate or a

testate proceeding the question of inclusion in, or exclusion from, the inventory

of a piece of property without prejudice to the final determination of ownership

in a separate action. Second, if the interested parties are all heirs to the estate,

or the question is one of collation or advancement, or the parties consent to the

assumption of jurisdiction by the probate court and the rights of third parties

are not impaired, then the probate court is competent to resolve issues on

ownership. Verily, its jurisdiction extends to matters incidental or collateral to

the settlement and distribution of the estate, such as the determination of the

status of each heir and whether the property in the inventory is conjugal or

exclusive property of the deceased spouse (Agtarap v. Agtarap, G.R. No.

177099, June 8, 2011).

Money Claim Against the Estate of a Decedent

The certification of non-forum shopping is required only for complaints

and other initiatory pleadings. The RTC erred in ruling that a contingent

money claim against the estate of a decedent is an initiatory pleading. In the

present case, the whole probate proceeding was initiated upon the filing of

the petition for allowance of the decedent's will. Under Sections 1 and 5,

Rule 86 of the Rules of Court, after granting letters of testamentary or of

administration, all persons having money claims against the decedent are

mandated to file or notify the court and the estate administrator of their

respective money claims; otherwise, they would be barred, subject to certain

exceptions.

Such being the case, a money claim against an estate is more akin to a

motion for creditors' claims to be recognized and taken into consideration in

Page 13 of 14

the proper disposition of the properties of the estate. In Arquiza v. Court of

Appeals, the Court explained thus:

x x x The office of a motion is not to initiate new

litigation, but to bring a material but incidental matter arising

in the progress of the case in which the motion is filed. A

motion is not an independent right or remedy, but is confined to

incidental matters in the progress of a cause. It relates to some

question that is collateral to the main object of the action and

is connected with and dependent upon the principal remedy.

(Emphasis supplied)

A money claim is only an incidental matter in the main action for the

settlement of the decedent's estate; more so if the claim is contingent since the

claimant cannot even institute a separate action for a mere contingent

claim. Hence, herein petitioner's contingent money claim, not being an

initiatory pleading, does not require a certification against non-forum

shopping (Sheker v. Estate of Alice O. Sheker, G.R. No. 157912, December

13, 2007)

Removal of Administrator by a Creditor

Concerning complaints against the general competence of the

administrator, the proper remedy is to seek the removal of the administrator in

accordance with Section 2, Rule 82. While the provision is silent as to who may

seek with the court the removal of the administrator, we do not doubt that a

creditor, even a contingent one, would have the personality to seek such relief.

After all, the interest of the creditor in the estate relates to the preservation of

sufficient assets to answer for the debt, and the general competence or good

faith of the administrator is necessary to fulfill such purpose (Hilado v. Court

of Appeals, G.R. No. 164108, May 8, 2009).

Change of Name

Republic v. Labrador mandates that a petition for

a substantial correction or change of entries in the civil registry should have as

respondents the civil registrar, as well as all other persons who have or claim to

have any interest that would be affected thereby. It cannot be gainsaid that

change of status of a child in relation to his parents is a substantial

correction or change of entry in the civil registry.

When a petition for cancellation or correction of an entry in the civil

register involves substantial and controversial alterations including those on

citizenship, legitimacy of paternity or filiation, or legitimacy of marriage, a strict

compliance with the requirements of Rule 108 of the Rules of Court is

mandated (Republic of the Philippines v. Coseteng-Magpayo, G.R. No.

189476, February 2, 2011).

The change of name contemplated under Article 376 and Rule 103

must not be confused with Article 412 and Rule 108. A change of ones name

under Rule 103 can be granted, only on grounds provided by law. In order to

Page 14 of 14

justify a request for change of name, there must be a proper and compelling

reason for the change and proof that the person requesting will be prejudiced

by the use of his official name. To assess the sufficiency of the grounds

invoked therefor, there must be adversarial proceedings.

In petitions for correction, only clerical, spelling, typographical and other

innocuous errors in the civil registry may be raised. Considering that

the enumeration in Section 2, Rule 108 also includes changes of name, the

correction of a patently misspelled name is covered by Rule 108. Suffice it to

say, not all alterations allowed in ones name are confined under Rule 103.

Corrections for clerical errors may be set right under Rule 108.

This rule in names, however, does not operate to entirely limit Rule 108

to the correction of clerical errors in civil registry entries by way of a summary

proceeding. As explained above, Republic v. Valencia is the authority for

allowing substantial errors in other entries like citizenship, civil status, and

paternity, to be corrected using Rule 108 provided there is an adversary

proceeding. After all, the role of the Court under Rule 108 is to ascertain the

truths about the facts recorded therein (Republic of the Philippines v.

Mercadera, G.R. No. 186027, December 8, 2010).

Amp/2011

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- BASICS BAD FAITH INSURANCEDokument0 SeitenBASICS BAD FAITH INSURANCEWARWICKJ100% (2)

- Motion To Dismiss For Lack of StandingDokument5 SeitenMotion To Dismiss For Lack of StandingPublic Knowledge97% (33)

- Forcible EntryDokument6 SeitenForcible EntryMariaKristinaJihanBanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Law ReviewerDokument42 SeitenRemedial Law ReviewerNicolo ManikadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specpro - Crimpro - Evid - Albano ReviewerDokument64 SeitenSpecpro - Crimpro - Evid - Albano ReviewerRaven PhantomlordNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On and Matrix of Selected Crimes Under Special Penal Code by Prof. Modesto Ticman, Jr.Dokument43 SeitenNotes On and Matrix of Selected Crimes Under Special Penal Code by Prof. Modesto Ticman, Jr.CM EustaquioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Tip by RianoDokument8 SeitenRemedial Tip by RianoakjdkljfakljdkflNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Law Review EsguerraDokument31 SeitenRemedial Law Review EsguerraGressa Lacson100% (3)

- Pleading Writing and Practice Under The 2019 Amended Rules of Court (Highlights of Rules 1 To 18)Dokument21 SeitenPleading Writing and Practice Under The 2019 Amended Rules of Court (Highlights of Rules 1 To 18)May Yellow100% (1)

- Rule 114 Case DigestDokument14 SeitenRule 114 Case DigestAnonymous B0aR9GdN100% (1)

- Civil Procedure BookDokument45 SeitenCivil Procedure Bookkamradi100% (1)

- Memorandum SBDDokument4 SeitenMemorandum SBDbrentonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual For Continuous Trial PDFDokument105 SeitenManual For Continuous Trial PDFCherry Jean Romano100% (1)

- RPC Ortega NotesDokument131 SeitenRPC Ortega NotesJenny-ViNoch keine Bewertungen

- Registry OrderDokument2 SeitenRegistry OrderUSA TODAY NetworkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines drug case plea bargain motionDokument3 SeitenPhilippines drug case plea bargain motionRaffy PangilinanNoch keine Bewertungen

- LMT Remedial 2015Dokument21 SeitenLMT Remedial 2015Marcus M. GambonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parsons Complaint File No. 2014-30,525 (09A) - Brewer NoticeDokument47 SeitenParsons Complaint File No. 2014-30,525 (09A) - Brewer NoticeNeil GillespieNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 - 2023 UP BOC Criminal Law LMTs v2Dokument18 Seiten5 - 2023 UP BOC Criminal Law LMTs v2Azel FajaritoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Villasis LMTDokument46 SeitenVillasis LMTANoch keine Bewertungen

- People V CusiDokument1 SeitePeople V Cusicmv mendoza0% (1)

- RTC Ruling on Violence Against Women AffirmedDokument5 SeitenRTC Ruling on Violence Against Women Affirmeddiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- PVB v. CallanganDokument1 SeitePVB v. CallanganJohney Doe100% (2)

- Lecture Notes Civil ProcedureDokument249 SeitenLecture Notes Civil ProcedurebiaylutanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doctrine of Hierarchy of Courts Case CompilationDokument157 SeitenDoctrine of Hierarchy of Courts Case CompilationNaethan Jhoe L. CiprianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appendix 17 of IRR of RA No. 9184 - Blacklisting GuidelinesDokument13 SeitenAppendix 17 of IRR of RA No. 9184 - Blacklisting GuidelinesJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 Syllabus Pol Pil PDFDokument110 Seiten2018 Syllabus Pol Pil PDFRatio DecidendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Castro V Secretary, GR No. 132174, Aug 20, 2001Dokument1 SeiteCastro V Secretary, GR No. 132174, Aug 20, 2001Lyle BucolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case lifts highlight key drug case rulingsDokument24 SeitenCase lifts highlight key drug case rulingsBen Dover McDuffinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sy vs. Young, 699 SCRA 8, June 19, 2013Dokument7 SeitenSy vs. Young, 699 SCRA 8, June 19, 2013Axel FontanillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Model Streamlines Pre-Trial Process and Settlement ConferencesDokument36 SeitenPhilippine Model Streamlines Pre-Trial Process and Settlement ConferencesIriz BelenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial LawDokument178 SeitenRemedial LawEpah SBNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Law Review Atty. Tranquil Salvador - Special ProceedingsDokument4 SeitenRemedial Law Review Atty. Tranquil Salvador - Special ProceedingsNayadNoch keine Bewertungen

- D2b - 5 People v. PadrigoneDokument2 SeitenD2b - 5 People v. PadrigoneAaron AristonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Furusawa Vs Sec of LaborDokument6 SeitenFurusawa Vs Sec of LaborMp CasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Casupanan Vs LaroyaDokument8 SeitenCasupanan Vs LaroyaRhenfacel ManlegroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bankruptcy Court Conflict Notice Seeks Counsel RemovalDokument103 SeitenBankruptcy Court Conflict Notice Seeks Counsel RemovalDavar100% (1)

- Sebastian V Bajar DigestDokument2 SeitenSebastian V Bajar Digestjeffdelacruz100% (2)

- SEC vs. MendozaDokument6 SeitenSEC vs. MendozaElreen Pearl AgustinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparing Old and New Rules on Evidence in the PhilippinesDokument65 SeitenComparing Old and New Rules on Evidence in the PhilippinesEyah LoberianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CA and RTC Error in Ordering Cancellation of Entries on Land TitleDokument36 SeitenCA and RTC Error in Ordering Cancellation of Entries on Land TitleJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compiled Digest - Legal EthicsDokument18 SeitenCompiled Digest - Legal EthicsEmma SchultzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salient Features of The Revised Guidelines For Continuous Trial of Criminal CasesDokument7 SeitenSalient Features of The Revised Guidelines For Continuous Trial of Criminal CasesVance CeballosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corpus v. Ochotorena DigestDokument2 SeitenCorpus v. Ochotorena DigestConcon FabricanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sps Dacudao vs. Secretary of Justice GonzalesDokument11 SeitenSps Dacudao vs. Secretary of Justice GonzalesaudreyracelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arellano University Remedial Law SyllabusDokument15 SeitenArellano University Remedial Law SyllabusMariya Klara MalaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Law 1 BarQsDokument5 SeitenConstitutional Law 1 BarQsペラルタ ヴィンセントスティーブNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 AUSL LMT Legal Ethics Draft PDFDokument14 Seiten2019 AUSL LMT Legal Ethics Draft PDFJo GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spec Pro Outline - SinghDokument10 SeitenSpec Pro Outline - SinghHaydn JoyceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Court 1 Syllabus OutlineDokument15 SeitenPractice Court 1 Syllabus OutlineFeb Mae San DieNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Canlas vs. Napico HomeownersDokument4 Seiten3 Canlas vs. Napico HomeownersAnonymousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judge Gener Gito Bulacan SyllabusDokument22 SeitenJudge Gener Gito Bulacan SyllabussejinmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRIMINAL LAW TIPSDokument54 SeitenCRIMINAL LAW TIPSPaula GasparNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus - Civil Procedure (JAC)Dokument32 SeitenSyllabus - Civil Procedure (JAC)Zedy MacatiagNoch keine Bewertungen

- REM 1 SyllabusDokument16 SeitenREM 1 SyllabuspatrixiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JurisdictionDokument12 SeitenJurisdictionDave A ValcarcelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rem 2 NotesDokument1.655 SeitenRem 2 NotesCerado AviertoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Remedial Law LMTDokument14 Seiten2016 Remedial Law LMTTom SumawayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notarial Register ZedDokument5 SeitenNotarial Register ZedIsidore Tarol IIINoch keine Bewertungen

- Revised Corporation CodeDokument15 SeitenRevised Corporation CodeM.K. TongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prof. EsguerraSurvey of Criminal Law Cases 2015Dokument36 SeitenProf. EsguerraSurvey of Criminal Law Cases 2015ED RCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arellano University Civil Procedure SyllabusDokument39 SeitenArellano University Civil Procedure SyllabusKaye RabadonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lakas Atenista Notes JurisdictionDokument8 SeitenLakas Atenista Notes JurisdictionPaul PsyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Callejo CrimDokument60 SeitenCallejo CrimMJ PerryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law FundamentalsDokument10 SeitenLabor Law FundamentalsMary Louise100% (1)

- Part 2 Political Law Reviewer by Atty SandovalDokument67 SeitenPart 2 Political Law Reviewer by Atty SandovalHazel Toledo MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arraignment and Pretrial ConferenceDokument1 SeiteArraignment and Pretrial Conferenceroyax1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pomoly Bar Reviewer Day 2 Am CivDokument111 SeitenPomoly Bar Reviewer Day 2 Am CivRomeo RemotinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Law (CivPro)Dokument21 SeitenRemedial Law (CivPro)Justin CebrianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appeals in The PhilippinesDokument8 SeitenAppeals in The PhilippinesLeandro-Jose C TesoreroNoch keine Bewertungen

- (FINAL) Hendy Abendan Et Al. Vs Exec. Secretary - ATL Draft PetitionDokument70 Seiten(FINAL) Hendy Abendan Et Al. Vs Exec. Secretary - ATL Draft PetitionRapplerNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPECIAL PROCEEDING SETTLEMENT OF ESTATESDokument34 SeitenSPECIAL PROCEEDING SETTLEMENT OF ESTATESJasmine Montero-GaribayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal EthicsDokument4 SeitenLegal EthicsJosh PascuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CivproDokument188 SeitenCivproCpreiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remediallaw AlbanoDokument15 SeitenRemediallaw AlbanoJosephine Dominguez RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edgar Barroso v. Honorable Judge George OmelioDokument4 SeitenEdgar Barroso v. Honorable Judge George OmeliojosephNoch keine Bewertungen

- RTC Judge's Authority to Deny Plea Bargaining in Drug Cases UpheldDokument15 SeitenRTC Judge's Authority to Deny Plea Bargaining in Drug Cases UpheldAngeline De GuzmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Key ConceptsDokument9 SeitenCivil Procedure Key ConceptsGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Doctrines in Special ProceedingsDokument14 SeitenCase Doctrines in Special Proceedingsbill locksley laurenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- CASELIST JDREM1 Converted Converted MergedDokument57 SeitenCASELIST JDREM1 Converted Converted MergedDiane JulianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Doctrines - Jurisdiction To Rule 37Dokument31 SeitenCase Doctrines - Jurisdiction To Rule 37Kaizer YganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vawc - GRN 179267 GarciaDokument44 SeitenVawc - GRN 179267 GarciaJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7610 - GRN 198732 CaballoDokument39 Seiten7610 - GRN 198732 CaballoJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adverse Claim - GRN L-29740 Arrazola PDFDokument14 SeitenAdverse Claim - GRN L-29740 Arrazola PDFJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nullity - GRN 247985 de SilvaDokument59 SeitenNullity - GRN 247985 de SilvaJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vawc - GRN 193960 DabalosDokument40 SeitenVawc - GRN 193960 DabalosJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nullity - GRN 209278 DatuDokument42 SeitenNullity - GRN 209278 DatuJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7610 - GRN 252267 EncinaresDokument46 Seiten7610 - GRN 252267 EncinaresJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7610 - GRN 252267 EncinaresDokument46 Seiten7610 - GRN 252267 EncinaresJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7610 - GRN 250671 TalocodDokument31 Seiten7610 - GRN 250671 TalocodJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nullity - GRN 242070 CalmaDokument51 SeitenNullity - GRN 242070 CalmaJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nullity - GRN 192718 MallilinDokument39 SeitenNullity - GRN 192718 MallilinJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nullity - GRN 242070 CalmaDokument51 SeitenNullity - GRN 242070 CalmaJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nullity - GRN 229272 TecagDokument22 SeitenNullity - GRN 229272 TecagJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adverse Claim - GRN 223660 Valderama PDFDokument49 SeitenAdverse Claim - GRN 223660 Valderama PDFJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adverse Claim - GRN L-29740 Arrazola PDFDokument14 SeitenAdverse Claim - GRN L-29740 Arrazola PDFJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adverse Claim - GRN 229408 CRDC PDFDokument68 SeitenAdverse Claim - GRN 229408 CRDC PDFJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nullity - GRN 192718 MallilinDokument39 SeitenNullity - GRN 192718 MallilinJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Court upholds adverse claim over notice of levy due to prior annotationDokument63 SeitenCourt upholds adverse claim over notice of levy due to prior annotationJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adverse Claim - GRN L-12760 Aguila PDFDokument19 SeitenAdverse Claim - GRN L-12760 Aguila PDFJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- GPPB Resolution No. 17-2021Dokument15 SeitenGPPB Resolution No. 17-2021JoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- GPPB Resolution No. 15. 2021Dokument29 SeitenGPPB Resolution No. 15. 2021JoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- GPPB Resolution No. 16-2021 (Delisting)Dokument5 SeitenGPPB Resolution No. 16-2021 (Delisting)JoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- LocalGovUnitsProcManual PDFDokument282 SeitenLocalGovUnitsProcManual PDFmarwinjsNoch keine Bewertungen

- GPPB Resolution No. 18-2021Dokument26 SeitenGPPB Resolution No. 18-2021JoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- GPPB Resolution No. 14-2021 - SEC Registration With SGDDokument5 SeitenGPPB Resolution No. 14-2021 - SEC Registration With SGDJoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- NEW APP Format (RA-11469)Dokument14 SeitenNEW APP Format (RA-11469)JoAnneGallowayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Circular On The Guideline For Emergency Procurement Under RA 11525.revisedDokument9 SeitenCircular On The Guideline For Emergency Procurement Under RA 11525.revisedtikki0219Noch keine Bewertungen

- Attorney Sam Randazzo's Response To Protective Order by Wind DeveloperDokument46 SeitenAttorney Sam Randazzo's Response To Protective Order by Wind DeveloperDennis AlbertNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic vs. Quintero-HamanoDokument7 SeitenRepublic vs. Quintero-HamanoHeidy BaduaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stewart Et Al v. Kroeker Et Al - Document No. 161Dokument3 SeitenStewart Et Al v. Kroeker Et Al - Document No. 161Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To Dismiss SampleDokument2 SeitenMotion To Dismiss Samplecredit analystNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practical - PRINTDokument21 SeitenPractical - PRINTJam Yap PagsuyoinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crusaders Broadcasting System, Inc. vs. NationalDokument1 SeiteCrusaders Broadcasting System, Inc. vs. NationalDeniel Salvador B. Morillo100% (1)

- Christine Varad v. Reed Elsevier Incorporated - Document No. 65Dokument3 SeitenChristine Varad v. Reed Elsevier Incorporated - Document No. 65Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dispute Over Jurisdiction Between RTC and SECDokument3 SeitenDispute Over Jurisdiction Between RTC and SECZainne Sarip BandingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mapulo Mining Association vs Secretary of AgricultureDokument15 SeitenMapulo Mining Association vs Secretary of AgricultureAriel MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nacnac Vs PeopleDokument8 SeitenNacnac Vs PeopleJohn CheekyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Santiago V VasquezDokument7 SeitenSantiago V VasquezAlthea Angela GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gov Uscourts Pamd 105376 44 0Dokument9 SeitenGov Uscourts Pamd 105376 44 0J DoeNoch keine Bewertungen