Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Chapter V Summary - Subtopics 1-20

Hochgeladen von

Lisa ColemanOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chapter V Summary - Subtopics 1-20

Hochgeladen von

Lisa ColemanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CHAPTER V- INTERPRETATION OF WORDS AND PHRASES

5.01. Generally

A word or phrase used in a statute may have an ordinary, generic, restricted, technical,

legal, commercial, or trade meaning. Which meaning should be given to a word or phrase in

statute depends upon what the legislature intended.

As a general rule, in interpreting the meaning and scope of a term used in the law, a

careful review of the whole law involved, as well as the intendment of law, ascertained from a

consideration of the statue as a whole, and not of an isolated part or a particular provision alone,

must be made to determine the real intent of the law.

Term used:

Void for vagueness is a declaration that a law is invalid because it is not sufficiently clear, or

that in terms of legislative delegation the authority is so extensive so as to lead to arbitrary

prosecutions.

5.02. Statutory definition.

The legislative definition controls the meaning of the statutory word, irrespective of any

other meaning the word or phrase may have in its ordinary or usual sense. Where a statute

defines a word or phrase employed therein, the word or phrase should not, by construction, be

given a different meaning. When the legislature gives a definition to a word, the meaning is

restricted within the terms of definitions. When the legislature gives meaning to a word as used

in the statute, it doesnt usurp the courts power to interpret the laws but merely legislates what

should form part of the law.

While definition of terms in a statute must be given all the weight due them in the

construction of the provision in which they are used, the terms or phrase being part and parcel of

the whole statue must be given effect in their entirety as a harmonious, coordinate, and integrated

unit.

5.03 Qualification of rule.

The statutory definition of a word or term as used in this Act is controlling only insofar

as the act is concerned. The definition cannot be applied for when the same statue is used in

other statutes.

The general rule that the statutory definition control the meaning of statutory words does

not apply when its application creates obvious incongruities, destroys one of the major purposes

of the act/statute, or becomes illogical as a result of a change in its factual basis. In such case, the

statutory definition will be regarded with the word given a different meaning so as to avoid

consequence.

5.04 Words construed in their ordinary sense.

The general rule in construing words and phrases is that in the absence of legislative

intent to the contrary, words and phrases should be given their plain, ordinary ,and common

usage meaning. The courts therefore assume that the lawmakers know the meaning of words and

the rules of grammar so as to yield its correct sense.

Words in statute should generally be given their ordinary or usual meaning. They should

not be given a strict or limited signification in the absence of a legislative intent to that effect.

5.05. General words construed generally

Maxims:

Generaliaverbasuntgeneraliterintelligenda means what is generally spoke shall be

generally understood.

Generale dictum generaliterestinterpretandum means a general statement is understood in

a general sense.

A word of general significance in a statute is to be taken in its ordinary and comprehensive

sense, unless it is shown that the word is intended to be given a different or restricted meaning.

The rule is expressed in the maxim generaliaverbasuntgeneraliterintelligendaand generale

dictum generaliterestinterpretandum.

Where a word used in a statue has both a restricted and general meaning, the general must

prevail over the restricted unless the nature of the subject matter or the context in which it is

employed clearly indicates that the limited is intended.

5.07 General term includes things that arise thereafter.

A word of general signification employed in a statute should be construed, In the absence

of the legislative intent to the contrary, to comprehend not only peculiar conditions at the time of

its enactment but those that may normally arise after its approval.

Such rule of construction is known as progressive interpretation, which extends the

application of a statue to all subjects and conditions within its general purpose or scope that

come into existence following its passage, thus keeping the legislative short-term and transitory.

Hence, statutes framed in general terms apply to new cases that arise, and to new subjects

that are created, and which come within their general scope and policy. It is a rule of statutory

construction that legislative enactments in general and comprehensive terms, prospective in

operation, apply alike to all persons, subjects and businesses within their general purview and

scope.

5.08 Words with commercial trade or meaning.

When words used in business is applied in a statute, it should not be given a new

interpretation, but should be given such trade or commercial meaning as has been general

understood among merchants. In the absence of legislative intent to the contrary, trade or

commercial terms are presumed to have been used in their trade or commercial sense.

This is applicable to tariff laws and laws of commerce. These laws should be construed as

universally understood by the importer or trade.

5.09 Words with technical or legal meaning

Words that have technical sense or those judicially construed to have a certain meaning

should be interpreted according to the sense in which they have been previously used although

the sense may vary from the strict or literal meaning of the words.

5.10. How identical terms in same statue are construed.

The general rule is that a word or phrase repeatedly used in a statue will bear the same

meaning throughout the statue.

The same word or substantially the same phrase appearing in different parts of the statue

will be accorded a generally accepted and consistent meaning, unless a different intention

appears or is clearly expressed.

The reason for this is that a word used in a statute in a given sense is presumed to be used

in the same sense throughout the law.

5.11 Meaning of word qualified by purposes of statue.

The meaning of a word or phrase may be qualified by the purpose which induced the

legislature to enact the statue. In construing a word or phrase, the court should adopt that

interpretation that accords best with the manifest purpose of the statue. If the language of the

statue is susceptible of two or more construction, that which gives effect to the manifest intent of

the lawmaker and promote the object for which the statute was enacted should be adopted, and

the construction that destroys other provisions of the statute or defeats the object the legislator

sought to attain should be rejected

The literal meaning of the word or phrase may be rejected if the result of adopting such

meaning will be to defeat the purpose which the legislature had in mind.

5.12 Word or phrase construed in relation to other provisions.

The general rule is at a word, phrase or provision should not be construed in isolation but

must be interpreted in relation to other provisions of the law.

5.13 Meaning of term dictated by context.

Maxim:

Verbaaccipiendasuntsecundummateriam means words are to be accepted or understood

according to the subject matter to which they deal with.

While ordinarily a word or term used in statute may be given the ordinary meaning, the

context in which a term or phrase is used may dictate a different sense. The context in which the

word is used oftentimes determines its meaning. The maxim applied here is

verbaaccipiendasuntsecundummateriam.

The context may also limit the meaning of what otherwise is a word of broad

signification. Finally, the context in which the same word is used in different parts of the statute

may give it a generic sense in one part and a limited meaning in another part.

5.14 Where the law does not distinguish.

When the law does not distinguish, the courts should not distinguish. Ubilex non

distinguit, necnosdistingueredebemus. The rule is a corollary of the principle that general words

and phrases in a statue should ordinarily be accorded their natural and general significance.

The rule requires that a general term or phrase should not be reduced into parts and one

part distinguished from another so as to justify its exclusion from the operation of the law. There

should be no distinction in the application of a statue where none is indicated.

A corollary principle is the rule that where the law does not make any exception, courts

may not except something therefrom unless there is compelling reason apparent in the law to

justify it.

The maxim ubilex non distinguitnecnosdistingueredebemusapplies not only in the

construction of general words and expressions used in the statue but also in the interpretation of

the rule laid down therein.

5.16 Disjunctive and conjunctive words.

The word or is disjunctive signify disassociation and independence of one thing from

other things enumerated. The use of or between two phrases connotes that either phrases

serves as qualifying phrase.

For instance where a tax statute imposes amusement tax on gross receipts of the

proprietor, lessee, OR operator of the amusement place, the word or is used disjunctively

since proprietor, lessee, and operator are implied as three distinct beings and that either of

the three should pay the tax separately and not as a whole.

However, or could sometimes be held to mean and, when the spirit or context of the

law so warrants. Example, in Sec. 2, Rule 112 of the Rules of Court, a municipal judge is

authorized to conduct preliminary examination or investigation. The or many mean and

since under the law the municipal judge can both conduct the first and second stages of

preliminary investigation.

Or could also mean that is to say, giving that which precedes it the same significance

as that which follows it.

On the other hand, and is a conjunction pertinently defined as meaning together with

joined with, added to, etc and is used to join word with word, phrase with phrase, clause

with clause. The word and does not mean or; it is a conjunction used to denote a joinder or

union.

And may also be a means to restrict the meaning of a broad word when a restrictive

word is separated by the word and. Thus when two words, one of which is broad and the other

restrictive, the restrictive word limits the meaning of the broad word. For instance in Rumaratevs

Hernandez, when the law speaks of possession and occupation, although and is used, both

are not to be taken as synonymous with one another. Possession is broader than occupation since

the latter includes constructive possession. The word occupation highlights the fact that in order

to qualify for the term occupation a persons possession of the land must exist.

And/or means that one word or the other may be taken accordingly as one or the other

will best effectuate the purpose intended by the legislature as gathered from the whole state. It

avoids the construction which by the use of or alone will exclude the combination of other

alternatives and by the use of and will not make the others effective when standing alone.

5.17. Noscitur a sociis.

The maxim, noscitur a sociis, states that where a particular word or phrase is ambiguous

in itself or is equally susceptible of various meanings, its correct construction may be made clear

and specific by considering the company of other words with which it is found. This is so

because a word or phrase in a statute is always used in association with other words or phrases,

and its meaning may thus be modified or restricted by the latter.

In accordance to noscitur a sociis, if most of the words in an enumeration of words in a

statue are used in their generic and ordinary sense, the rest of the words should be construed the

same way.

5.18 Application of rule.

In sec 13(3), Art. XI of the Constitution grants the Ombudsman the power to Direct the

officer concerned to take action against a public official at fault, and recommend his removal,

suspension, demotion, fine, censure, or prosecution with regard to noscitur a sociis, the word

suspension should be given the same sense as its associated words, all of which are punitive in

nature. Suspension should not be taken as a prevention but as a penalty.

In Carandangvs Santiago, the offended party argues that physical injuries mentioned in

Art. 33 of the Civil Code (In cases of defamation, fraud, and physical injuries a civil action for

damages, entirely separate and distinct from the criminal action, may be brought by the injured

party) does not include frustrated homicide because it is not under physical injuries as stated

in the Revised Penal Code. However, the court contended that should be understood in its

ordinary sense, such as to mean any form of bodily harm. This is because the other terms,

defamation and fraud are understood in their ordinary sense since they are not specifically

defined in the RPC.

5.19 Ejusdem generis.

The general rule is that where a general word or phrase follows an enumeration of

particular and specific words of the same class or where the latter follow the former, the general

word or phrase is to be construed to include, or to be restricted to, persons, things, or case, of the

same class as those that were mentioned. This canon of statutory construction is known as

ejusdem generis meaning of the same kind or specie.

The purpose of such is to give effect to both the particular and general words, by treating

the particular words as indicating of the class and the general words as indicating all that is

embraced in such class.

This is based on the preposition that had the legislature intended the general words to be

used in their generic and unrestricted sense, it would not have enumerated specific words. The

presumption is that legislators are thinking about particularization.

5.20 Illustration of the rule.

Where an act makes unlawful the distribution of electoral propaganda such as gadgets,

pens, lighters, fans, flashlights, athletic goods or materials and the like, the term and the like

does not include taped jingles for campaign purposes since the enumerated terms are all of the

same class, that is tangible items.

5.21 Limitations of ejusdem generis

To be applicable, the rule of ejusdem generis requires that the following requisites

concur: (1) a statute contains an enumeration of particular and specific words, followed by a

general word or phrase; (2) the particular and specific words constitute a class or are of the same

kind; (3) the enumeration of the particular ajd specific words is not exhaustive or is not merely

by examples; and (4) there is no indication of legislative intent to give the general words or

phrases a broader meaning.

The general rule that the general term may be restrained by specific words associated

with it is applicable only to cases where, except for one general term, all the items in an

enumeration belong to or fall under one specific class or are of the same nature. If the

enumeration of specific things have no distinguishable common characteristics and greatly differ

from one another, the rule of ejusdem generis does not apply.

Nor does the rule of ejusdem generis apply where the enumeration of the particular and

specific words is exhaustive. If the specific words embrace all persons or objects of the class

designated by the enumeration, the general words should include those comprehended in the

general classification and beyond the specified class.

Where a statute uses a general word, followed by an enumeration of specific words

embraced within the general word merely as examples, the enumeration does not thereby restrict

the meaning of the general word, but should include others of the same class although not

enumerated therein.

Ejusdem generis does not require the rejection of general terms entirely. The rule is

intended merely as an aid in ascertaining the intention of the legislature and is taken in

connection with the other rules of construction. It should been applied so widely so as to defeat

the intention of the law. Thus, the rule shall not apply on consideration of the whole law on the

subject and the purpose sought, it appears that the legislature intended the general words to go

beyond the class designated by the specific and particular words in the enumeration. In short the

rule of ejusdem generis is not of universal application, it should be used to carry out, not to

defeat the intent or purpose of the law.

The rule ejusdem generis is used to ascertain the intent of the law. If the intent clearly

appears from other parts of the law, and such intent thus clearly manifested is contrary to the

result which will be reached by applying the rule, the rule must give way in favor of legislative

intent.

5.22 Expressio unnius est exclusion alterius

The maxim expression unnius est exclusio alterius means that express mention of one

person, thing, or consequences implies the exclusion of all others

The rule is formulated in a number of ways. One variation is the principle that what is

expressed puts an end to that which is implied (expressum facit cesare tacitum)

Another variation of the rule is that a general expression followed by exceptions

therefrom implies that those which do not fall under the exceptions come within the scope of the

general expression. It is explained by the maxim exceptio firmat regulam in casibus non exceptis,

which means a think not being executed must be regarded as coming within the purview of the

general rule.

Another variation is the axiom that the expression of one or more things of a class implies

that the exclusion of all not expressed, even though all would have been implied had none been

expressed. It is based on the fact that the mind of people usually are addressed specially to the

particularization, and that the generalities, thought broad enough to comprehend other fileds if

they stood alone, are used in the contemplation of that upon which the minds of the parties are

centered.

The variations of expressio unnius est exclusio alterius are canons of restrictive

interpretation. They are based on rules of logic and the natural workings of the human mind.

They preceed from the premise that the legislature would not have made specified enumerations

in a statute if they did not intend to restrict its meaning and confine its terms to those expressly

mentioned.

It is the opposite of the doctrine of necessary implication which states that What is

implied in a statute is as much a part thereof as that which is expressed. Expression unnius is the

opposite of the doctrine of necessary implication.

5.23 Negative-opposite doctrine.

Negative-opposite doctrine or argmentum a contrario is the principle that what is

expressed puts an end to that which is implied.

5.24 Expressio unnius application

The rule expressio unnius est exclusion alterius and its corollary canons are generally

used in the construction of statutes granting powers, creating rights, and remedies, restricting

common rights and imposing penalties and forfeitures.

Pursuant to this rule, where a statute directs the performance of certain acts by a

particular person or class of persons, it implies that it shall not be done otherwise by a different

person or class. For instance, in actions for libel, the statute which provides that preliminary

investigations for criminal actions for written defamation shall be conducted by the provincial or

city fiscal of the province or city or by the municipal court of the city or capital of the province

where such actions may be instituted prohibits all other municipal courts from conducting such

preliminary investigations.

If a statute enumerates the things upon which it is to operate, everything else must

necessarily, and by implication, be excluded.

5.25 Limitation of the rule

Expressio unnius is not a rule of law. It is a mere tool of statutory construction and is not

universal in application. It is no more than an auxiliary rule which will be ignored if other

circumstances indicate that the enumeration was not intended to be exclusive. The reason to this

is that there are circumstances indicating that the enumeration is not intended to be exclusive

because fact shows that to exclude the provision and others not mentioned therein would produce

undesirable consequences not intended by its framers.

The maxim expression unnius does not apply where enumeration is by way of example to

remove doubts only, such as in cases where a general term is follow with such as.

The maxim does not apply in cases where a statute appears on its face to limit the

operation of its provision to particular persons or things by enumerating them, but not reason

exists why other persons or things not enumerated should not have been included and manifest

injustice will follow by not including them.

The maxim may also be disregarded if adherence thereto would cause inconvenience,

hardship and injury to the public interest.

Lastly, where the legislative intent shows that the enumeration is not exclusive, the

maxim does not apply.

5.26 Doctrine of casus omissus

Casus omissus pro omisso habendus est states that a person, object, or thing omitted from

an enumeration must be held to have been omitted intentionally. The maxim operates and pplies

only if and when the omission has been clearly established, and in such a case what is omitted in

the enumeration may not by construction be included therein.

The rule does not apply where it is shown that the legislature did not intend to exclude

the person, thing, or object from the enumeration. If such legislative intent is clearly indicated,

the court may supply the omission if to do so will carry out the clear intent of the legislature and

will not do violence to its language.

5.27 Doctrine of last antecedent

Qualifying words, restrict or modify only the words or phrases to which they are

immediately associated. They do not qualify words or phrases which are distantly or remotely

located. In other words, in the absence of legislative intent to the contrary, preferential and

qualifying words and phrases must be applied only to their immediate or last antecedent, and not

to the other remote words.

This rule of legal hermeneutics is commonly known as doctrine of last antecedent. It

means that a qualifying word or phrase should be understood as referring to the nearest

antecedent. The maxim expressive of this rule is ad proximum atencendents fiat relatio nisi

impediatar sententia which means that relative words refer to the nearest antecedents, unless the

context otherwise requires.

5.29 Exception of the doctrine

Where the intention of the law is to apply the phrase to all antecedents embraced in the

provision, the same should be made extensive to the whole. Slight indication of legislative intent

so to extend the relative term is sufficient.

5.30 Reddendo singular singlis

The maxim means referring each to each; referring each phrase or expression to its

appropriate object or let each be put in its proper place, that is, the words should be taken

distributively. As a rule, the maxim requires that the antecedents and consequences should be

read distributively to the effect that each word is to be applied to the subject to which it appears

by context most appropriately related and to which it is most applicable.

5.31 provisos, generally

The office of proviso is either to limit the application of the enacting clause, section, or

provision of a statue, or to except something therefrom, or to qualify or restrain its generality, or

to exclude some possible ground of misinterpretation of it, as extending to cases not intended by

the legislature to be brought within its purview. Its primary purpose is to limit or restrict the

general language or operation of the statute, not to enlarge it.

A proviso is commonly found at the end of a section, or provision of a statute, and is

introduced, as a rule, by the word provide or but nothing therein. The use of the word

provided however does not necessarily make the clause or phrase to which it is associated a

proviso.

5.32 Proviso may enlarge the scope,

Sometimes the legislature does not use proviso in its technical correctness so it may

enlarge the scope of law instead of limiting it. Thus where there is ambiguity, the courts must

ascertain the intent of the legislature.

5.33 Proviso as additional legislation

A proviso may assume the role of an additional legislation. It has been held that the

usual and primary office of a proviso is to limit generalities and exclude from the cope of the

statue that which otherwise would be within its terms. But it may sometimes mean simply

additional legislation.

5.34 What proviso qualifies

The proviso qualifies or modifies only the phrase immediately preceeding it or restrains

or limits the generality of the clause that it immediately follows. It should be confined to that

which directly precedes it, or to the section to which it has been appended, unless it clearly

appears that the legislature intended it to have a wider scope.

5.35 Exception

The rule that a proviso should be construed to qualify only the immediately preceding

part of the section to which it is attached is true only if no contrary legislative intent is indicated.

5.36 Repugnancy between proviso and main provision

A proviso should be construed to harmonize with the main provision, not destroy it.

However, where there is irreconcilable repugnancy between a proviso and the main provision,

that which is located in a later portion of the statute prevails, unless there is a legislative intent to

the contrary or such construction will destroy the whole statute.

5.37 Exceptions

An exception consists of that which would otherwise be included in the provision from

which it is excepted. It is a clause that exempts something from the operations of a statute by

express words, such as words as except, unless, otherwise, and shall not apply.

5.38 Exception and proviso distinguished

An exception exempts something absolutely from the operations of a statue by express

words in the enacting clause. A proviso defeats its operation conditionally.

An exception takes out of the statute something that otherwise would be part of the

subject matter. A proviso avoids them by way of defeasance or excuse.

An exception is generally a part of the enactment itself. But when the enactment modified

by engrafting upon it a new provision, by way of amendment, providing conditionally for a new

case, it is in the nature of a proviso.

5.40 Saving clause

A saving clause is a clause in a provision of law which operates to except from the effect

of the law what the clause provides, or to save something which would otherwise be lost. Usually

it is used to except or save something from the effect of a repeal of a statute.

It is to be construed in the light of the intent or purpose which the legislature had in mind

providing it in a statute the principal consideration being to effectuate such intent or carry out

such purpose.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Interpreting Words and Phrases in StatutesDokument14 SeitenInterpreting Words and Phrases in StatutesAna Marie Faith CorpuzNoch keine Bewertungen

- REVIEWER STATCON FinalsDokument10 SeitenREVIEWER STATCON FinalsrheyneNoch keine Bewertungen

- StatCon FinalsDokument5 SeitenStatCon FinalsElla CardenasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statcon Reviewer FinalsDokument10 SeitenStatcon Reviewer FinalsnobodybutcazzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 5 Interpretation of Words and PhrasesDokument24 SeitenChapter 5 Interpretation of Words and PhrasesmichelledugsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bukidnon State University College of LawDokument26 SeitenBukidnon State University College of LawKaye Kiikai OnahonNoch keine Bewertungen

- INTERPRET LAW TO UPHOLD RATHER THAN DESTROYDokument5 SeitenINTERPRET LAW TO UPHOLD RATHER THAN DESTROYRachel LeachonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpretation of Words and PhrasesDokument52 SeitenInterpretation of Words and PhrasesFebe TeleronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit-5 IosDokument5 SeitenUnit-5 IosKanishkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Construction and Interpretation of Words and Phrases.Dokument16 SeitenConstruction and Interpretation of Words and Phrases.Marc CosepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter V Notes AgpaloDokument18 SeitenChapter V Notes AgpaloAliya Safara AmbrayNoch keine Bewertungen

- STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION GUIDEDokument74 SeitenSTATUTORY CONSTRUCTION GUIDEGayle AbayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction ReviewerDokument9 SeitenStatutory Construction ReviewerKevin G. PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sources of Legislative IntentDokument34 SeitenSources of Legislative IntentRuss TuazonNoch keine Bewertungen

- STAT Con Made Easier For FreshmenDokument53 SeitenSTAT Con Made Easier For FreshmenAnonymous GMUQYq8Noch keine Bewertungen

- SadaDokument23 SeitenSadaByron MeladNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hand-Outs For Intro To LawDokument8 SeitenHand-Outs For Intro To LawChristian ViernesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction Made Easy by A Freshman Statutory Construction 2012 Rule1. Apply The Law When It Is CLEAR. Do Not Interpret or CONSTRUEDokument23 SeitenStatutory Construction Made Easy by A Freshman Statutory Construction 2012 Rule1. Apply The Law When It Is CLEAR. Do Not Interpret or CONSTRUEPat P. MonteNoch keine Bewertungen

- August 9,2018 Notes in Week 6 and 7Dokument3 SeitenAugust 9,2018 Notes in Week 6 and 7QueenVictoriaAshleyPrietoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statcon ReviewerDokument24 SeitenStatcon ReviewerPamelaMariePatawaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legislative IntentDokument2 SeitenLegislative IntentMabeliene CieloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction Made Easy by Aging LawyerDokument31 SeitenStatutory Construction Made Easy by Aging LawyerVincent Tan100% (1)

- Yashika Gupta ASSIGNMENT 2Dokument5 SeitenYashika Gupta ASSIGNMENT 2Yashika guptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- StatconDokument17 SeitenStatconKaye Kiikai Onahon0% (1)

- Stat Con DigestsDokument7 SeitenStat Con DigestsnoonalawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpretation Of Statutes notes 3Dokument76 SeitenInterpretation Of Statutes notes 3sredhaappleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction (2018 - 03 - 06 17 - 15 - 54 UTC)Dokument30 SeitenStatutory Construction (2018 - 03 - 06 17 - 15 - 54 UTC)samNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aginglawyer: Statutory Construction Made Easy by A FreshmanDokument35 SeitenAginglawyer: Statutory Construction Made Easy by A FreshmanNaiza Mae R. Binayao100% (1)

- Unit 2 IosDokument4 SeitenUnit 2 IosKanishkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IOS Unit4 RulesOfInterpretationDokument5 SeitenIOS Unit4 RulesOfInterpretationKirubakar RadhakrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stat Con WholeDokument68 SeitenStat Con WholeNICK CUNANANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name: Sharia Shoaib Semester: 5 Roll No.: 1821 Subject: Interpretation of StatutesDokument3 SeitenName: Sharia Shoaib Semester: 5 Roll No.: 1821 Subject: Interpretation of StatutesShariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- STATUTORY INTERPRETATION AND CONSTRUCTIONDokument10 SeitenSTATUTORY INTERPRETATION AND CONSTRUCTIONMohd Shaji100% (1)

- Examples of Statutory Construction Rules From Case LawDokument2 SeitenExamples of Statutory Construction Rules From Case LawMarx Earvin Torino100% (1)

- Technical and legal meaning of words in statutesDokument2 SeitenTechnical and legal meaning of words in statutesKarla KatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ejusdem Generis ProjectDokument13 SeitenEjusdem Generis ProjectMegha BoranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PointDokument3 SeitenPointangelica poNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statcon Chapter1Dokument10 SeitenStatcon Chapter1roxyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Five - Agpalo StatconDokument10 SeitenChapter Five - Agpalo StatconCelinka ChunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Long Title and Preamble Guide Statute InterpretationDokument11 SeitenLong Title and Preamble Guide Statute InterpretationAmogh PareekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dr. RAJINDER KAUR RANDHAWA's Online Exam Questions for LLB 406 Interpretation of StatutesDokument12 SeitenDr. RAJINDER KAUR RANDHAWA's Online Exam Questions for LLB 406 Interpretation of StatutesNiraj PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Golden RuleDokument4 SeitenGolden RuleLiew Jia HeNoch keine Bewertungen

- IOS NotessDokument20 SeitenIOS Notesssanjusanjana098765Noch keine Bewertungen

- Interpretation of StatutesDokument23 SeitenInterpretation of StatutesAayushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory ConstructionDokument14 SeitenStatutory ConstructionGlenn PinedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- StatCon Q and A Final DraftDokument18 SeitenStatCon Q and A Final DraftRodel LouronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpreting laws through principles of statutory constructionDokument2 SeitenInterpreting laws through principles of statutory constructiontokitoki24Noch keine Bewertungen

- IOS AnswersDokument56 SeitenIOS Answersbagalli tejeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory interpretation and doctrinesDokument35 SeitenStatutory interpretation and doctrinesdeepak sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpretation of Statutes NotesDokument39 SeitenInterpretation of Statutes NotesGurjot Singh KalraNoch keine Bewertungen

- BASIC PRINCIPLES OF STATUTORY INTERPRETATIONDokument6 SeitenBASIC PRINCIPLES OF STATUTORY INTERPRETATIONTANUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ios ShashankDokument14 SeitenIos ShashankM.AnudeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction AssignmentDokument5 SeitenStatutory Construction AssignmentJessie James YapaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agpalo Chapters 6-11Dokument46 SeitenAgpalo Chapters 6-11Audrey DacquelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction ReviewerDokument15 SeitenStatutory Construction ReviewerGab EstiadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IOs Assgn - Interpretation of StatutesDokument15 SeitenIOs Assgn - Interpretation of StatutesHarsh VermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Principles of InterpretationDokument4 SeitenGeneral Principles of Interpretationkartik bansalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Terminology: A Comprehensive Glossary for Paralegals, Lawyers and JudgesVon EverandLegal Terminology: A Comprehensive Glossary for Paralegals, Lawyers and JudgesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mastering Legal Vocabulary For Law Students: Learn Contractual Phrases, Prepositions, and All Other Legal TerminologyVon EverandMastering Legal Vocabulary For Law Students: Learn Contractual Phrases, Prepositions, and All Other Legal TerminologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. VeraDokument2 SeitenPeople v. Vera09367766284Noch keine Bewertungen

- Persons and Family RelationsDokument40 SeitenPersons and Family RelationsMiGay Tan-Pelaez96% (23)

- People Vs DacuycuyDokument6 SeitenPeople Vs DacuycuyLisa ColemanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who are indigenous peoples? Understanding definitions and differencesDokument1 SeiteWho are indigenous peoples? Understanding definitions and differencesLisa ColemanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Declarador V GubatonDokument5 SeitenDeclarador V GubatonLisa ColemanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction Agpstatutory Construction Agpalo - PdfaloDokument70 SeitenStatutory Construction Agpstatutory Construction Agpalo - PdfaloJumen Gamaru TamayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Castro Vs JBC (Digest)Dokument2 SeitenDe Castro Vs JBC (Digest)Lisa Coleman100% (2)

- Philippine Law Reviewers Explains Criminal Law Book 1 Articles 21-30Dokument11 SeitenPhilippine Law Reviewers Explains Criminal Law Book 1 Articles 21-30Liezel SimundacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caihte: DecisionDokument40 SeitenCaihte: DecisionLyka Dennese SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Finance - Application Form - Student Finance Forms - GOV - UkDokument1 SeiteStudent Finance - Application Form - Student Finance Forms - GOV - UkIlko MirchevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Western Guaranty Corp. vs. CADokument2 SeitenWestern Guaranty Corp. vs. CABananaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Destination 2 (12A)Dokument3 SeitenDestination 2 (12A)oldhastonian100% (1)

- Promoting Human Rights Through Science, Education and CultureDokument10 SeitenPromoting Human Rights Through Science, Education and Culturekate saradorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic Act No 7279 (Lina Law)Dokument22 SeitenRepublic Act No 7279 (Lina Law)Jeanne AshleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notice To Court and All Court OfficersDokument27 SeitenNotice To Court and All Court OfficersMisory96% (113)

- IBP GOVERNOR DISBARMENTDokument3 SeitenIBP GOVERNOR DISBARMENTMargie Marj GalbanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clyde Armory Files Lawsuit Claiming Gun Stores Are EssentialDokument34 SeitenClyde Armory Files Lawsuit Claiming Gun Stores Are EssentialJulie WolfeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shabtay Versus Levy SynagogueDokument46 SeitenShabtay Versus Levy SynagogueLos Angeles Daily News100% (1)

- Dar05152019 PDFDokument5 SeitenDar05152019 PDFAnonymous Ydz9wH6VTNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAA guidance for EASA MOE appendicesDokument3 SeitenCAA guidance for EASA MOE appendicesShakil MahmudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Request For Availability of Funds For PLDT LineDokument4 SeitenRequest For Availability of Funds For PLDT LineMarco Arpon100% (1)

- Calculating Labour and Material Cost FluctuationsDokument10 SeitenCalculating Labour and Material Cost FluctuationsChinthaka AbeygunawardanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- THE REPUBLIC vs. KWAME AGYEMANG BUDU AND 11 OTHERS EX PARTE, COUNTY HOSPITAL LTDDokument21 SeitenTHE REPUBLIC vs. KWAME AGYEMANG BUDU AND 11 OTHERS EX PARTE, COUNTY HOSPITAL LTDAbdul-BakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V Dadulla 642 SCRA 432Dokument15 SeitenPeople V Dadulla 642 SCRA 432Makati Business ClubNoch keine Bewertungen

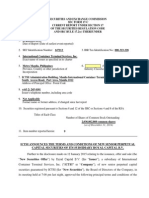

- ICTSI: Terms of Share IssuanceDokument3 SeitenICTSI: Terms of Share IssuanceBusinessWorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- TIMTA Annex A Instructional Guide-Feb. 17, 2021Dokument7 SeitenTIMTA Annex A Instructional Guide-Feb. 17, 2021Jeanette LampitocNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Research Project On-: Relevancy of Electronic Records and Its Admissibility in Criminal ProceedingsDokument23 SeitenA Research Project On-: Relevancy of Electronic Records and Its Admissibility in Criminal ProceedingsvineetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taxation Law - Leading Case CIT (W.B.) VS Anwar Ali AIR 1970 S.C. 1782Dokument5 SeitenTaxation Law - Leading Case CIT (W.B.) VS Anwar Ali AIR 1970 S.C. 1782Sunil SadhwaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Methods and Techniques for Collecting Intelligence InformationDokument2 SeitenMethods and Techniques for Collecting Intelligence InformationrenjomarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peace Process in ColombiaDokument5 SeitenPeace Process in ColombiaYoryina R. RetamozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indo Lanka AccordDokument9 SeitenIndo Lanka AccordfdesertNoch keine Bewertungen

- Larry Leonhardt, Dan Laursen, and Rick Rodriquez, Rodriquez Farms, Inc. v. Western Sugar Company, A Corporation, 160 F.3d 631, 10th Cir. (1998)Dokument16 SeitenLarry Leonhardt, Dan Laursen, and Rick Rodriquez, Rodriquez Farms, Inc. v. Western Sugar Company, A Corporation, 160 F.3d 631, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uppsc - Apo - Prelims 2019 PDFDokument6 SeitenUppsc - Apo - Prelims 2019 PDFBikashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Widens Norcilus, A072 041 927 (BIA June 2, 2017)Dokument16 SeitenWidens Norcilus, A072 041 927 (BIA June 2, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pension PapersDokument11 SeitenPension PapersNandaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- South Asia Tribune Weekly UKDokument32 SeitenSouth Asia Tribune Weekly UKShahid KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDokument14 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen