Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Media in Pakistan

Hochgeladen von

Mir Ahmad FerozCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Media in Pakistan

Hochgeladen von

Mir Ahmad FerozCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Media in Pakistan provides information on television, radio, cinema, newspapers,

and magazines in Pakistan. Veteran dissident and intellectualNoam Chomsky stated in an interview

which he repeated some of his well-known comments about the control of the media, he said: I spent

three weeks in India and a week in Pakistan. A friend of mine here, (he was in London when he was

interviewed) Iqbal Ahmed, told me that I would be surprised to find that the media in Pakistan is more

open, free and vibrant than that in India. He added: In Pakistan, I listened to and read the media which

go to a increasingly large part of the population. Apparently, the government, no matter how repressive it

is, is willing to say to them that you have your fun, we are not going to bother you. So they dont interfere

with it.

[1]

Christine Fair, a senior political analyst and specialist in South Asian political and military affairs at

the Rand Corporation praised the Pakistani Media as a role model and an example for other Muslim

countries to follow by stating "The only hope for Pakistanis is that the media will continue to mobilise

people. The media have done a great job, even if they are at times very unprofessional, and have to

come to term with the limits between journalism and political engagement."

[2]

Contents

[hide]

1 Overview

2 History

3 Role in exposing corruption

4 Challenges

5 International co-operation

o 5.1 Pakistan - US Journalists Exchange Program

o 5.2 International Center for Journalists

6 Regulation

o 6.1 History

o 6.2 Legal framework

6.2.1 Constitution

6.2.2 Media laws

6.2.3 Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority

7 Television

8 Radio

9 Cinema

10 Newspapers and magazines

11 News Agencies

o 11.1 Press Council and Newspaper Regulation

12 See also

13 References

14 External links

Overview[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please

help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced

material may be challenged and removed. (November 2013)

Since 2002, the Pakistani media has become powerful and independent and the number of private

television channels has grown from just three state-run channels in 2000 to 89 in 2012, according to

the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority. Most of the private media in Pakistan flourished

under the Musharraf regime.

Pakistan has a vibrant media landscape and enjoys independence to a large extent. After having been

liberalised in 2002, the television sector experienced a media boom. In the fierce competitive environment

that followed commercial interests became paramount and quality journalism gave way to sensationalism.

Although the radio sector has not seen similar growth, independent radio channels are numerous and

considered very important sources of information - especially in the rural areas.

The Pakistani media landscape reflects a multi-linguistic, multi-ethnic and class-divided society. There is

a clear divide between Urdu and English media. The Urdu media, particularly the newspapers, are widely

read by the masses - mostly in rural areas. The English media is urban and elite-centric, is more liberal

and professional compared to the Urdu media. English print, television and radio channels have far

smaller audiences than their Urdu counterparts, but have greater leverage among opinion makers,

politicians, the business community and the upper strata of society.

Pakistan has a vibrant media landscape; among the most dynamic and outspoken in South Asia. To a

large extent the media enjoys freedom of expression. More than 89 television channels beam soaps,

satire, music programmes, films, religious speech, political talk shows, and news of the hour. Although

sometimes criticised for being unprofessional and politically biased, the television channels have made a

great contribution to the media landscape and to Pakistani society.

Radio channels are numerous and considered a very important source of information - especially in the

rural areas. Besides the state channel Radio Pakistan, a number of private radios carry independent

journalistic content and news. But most radio content is music and entertainment. There are hundreds of

Pakistani newspapers from the large national Urdu newspapers to the small local vernacular papers.

Pakistan's media sector is highly influenced by the ownership structure. There are three dominating

media moguls, or large media groups, which to some extent also have political affiliations. Due to their

dominance in both print and broadcast industries all three media groups are very influential in politics and

society.

[2]

History[edit]

The media in Pakistan dates back to pre-partition years of British India, where a number of newspapers

were established to promote a communalistic or partition agenda. The newspaper Dawn, founded

by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and first published in 1941, was dedicated to promoting for an independent

Pakistan. The conservative newspaper, Nawa-i-Waqt, established in 1940 was the mouthpiece of the

Muslim elites who were among the strongest supporters for an independent Pakistan.

In a sense, Pakistani print media came into existence with a mission to promulgate the idea of Pakistan,

which was seen as the best national option for the Muslim minority in British India and as a form of self-

defence against suppression from the Hindu majority.

[2]

Role in exposing corruption[edit]

Since the introduction of these vibrant TV channels, many major corruption cases and scams have been

unveiled by journalists. Notable among them are:

The Pakistan Steel Mills Rs.26 billion scam;

[3]

National Insurance Company Limited scandal;

[4]

Bribery and corruption in Pakistan International Airlines which caused losses of $500 million;

[5]

Embezzlement in Pakistan Railways causing massive financial losses;

[6]

Hajj corruption case;

[7]

NATO containers' case where 40 containers heading for ISAF in Afghanistan went missing;

[8]

Rental power projects corruption

[9]

Ephedrine quota case, a scandal involving the son of former Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gillani to

pressure officials of the Health Ministry to allocate a quota of controlled chemical ephedrine to two

different pharmaceutical companies.

[10]

Malik Riazs 'Media Gate' in which the son of Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry is said to

have taken money from Malik Riaz to give favourable decisions from the Supreme Court.

Malik Riazs case proved that the media can hold the judiciary and even itself accountable, says Javed

Chaudhry, columnist and anchorperson working with Express News. This case, along with the missing

persons' case has established impartiality and credibility of the media in its fight against corruption.

Chaudhry feels, like many others in country, that the media in Pakistan has become free and fair during

the last decade. The Pakistani media has covered the journey of 100 years in just 10 years, but their

curiosity and thrust for revelation does not end and that is what drives the media.

[11]

Challenges[edit]

According to a report by the UK Foreign Office, Pakistans media environment continued to develop and,

in many cases, flourish. Since opening up in 2002, the number and range of media outlets has

proliferated, so that Pakistanis now have greater access than ever before to a range of broadcasting

through print, television and online media. The increased media penetration into most aspects of

Pakistani life has created challenges as well as opportunities, as both the journalistic community and

politicians and officials build their understanding of effective freedom of expression and responsible

reporting.

[12]

However, in 2011, Reporters Without Borders listed Pakistan as one of the ten most deadly places to be

a journalist. As the War in North-West Pakistan continues, there have been frequent threats against

journalists. The proliferation of the media in Pakistan since 2002 has brought a massive increase in the

number of domestic and foreign journalists operating in Pakistan. The UK Foreign Office states that it is

vital that the right to freedom of expression continues to be upheld by the Pakistani Government. This

was highlighted by an event supporting freedom of expression run by the European Union in Pakistan,

which the United Kingdom supported.

[13]

Journalists secret fund List

International co-operation[edit]

Pakistan - US Journalists Exchange Program[edit]

Since 2011, the East-West Center (EWC), headquartered in Honolulu, Hawaii, have been organising the

annual Pakistan - United States Journalists Exchange program. It was launched and designed to

increase and deepen public understanding of the two countries and their important relationship, one that

is crucial to regional stability and the global war on terrorism. While there have been many areas of

agreement and cooperation, deep mistrust remains between the two, who rarely get opportunities to

engage with each other and thus rely on media for their information and viewpoints. Unresolved issues

continue to pose challenges for both countries.

This exchange offers U.S. and Pakistani journalists an opportunity to gain on-the-ground insights and

firsthand information about the countries they visit through meetings with policymakers, government and

military officials, business and civil society leaders, and a diverse group of other community members. All

participants meet at the East-West Center in Hawaii before and after their study tours for dialogues

focused on sensitive issues between the two countries; preconceived attitudes among the public and

media in both the United States and Pakistan; new perspectives gained through their study tours; and

how media coverage between the two countries can be improved. Ten Pakistani journalists will travel to

the United States and ten U.S. journalists will travel to Pakistan. This East-West Center program is

funded by a grant from the U.S. Embassy Islamabad Public Affairs Section.

The program provides journalists with valuable new perspectives and insights on this critically important

relationship, a wealth of contacts and resources for future reporting, and friendships with professional

colleagues in the other country upon whom to draw throughout their careers.

[14]

International Center for Journalists[edit]

In 2011, the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), a non-profit, professional organisation located

in Washington, D.C. launched the U.S. - Pakistan Professional Partnership in Journalismprogram,

which is a three-year, multi-phase program which will bring 128 Pakistani media professionals to the

United States and send 30 U.S. journalists to Pakistan. Journalists will study each other's cultures as they

are immersed in newsrooms in each country.

English-speaking Pakistanis will receive four-week internships at U.S. media organizations, and non-

English speakers will spend half that time.

The program will be knit throughout with events and opportunities to experience U.S. life, showcasing its

diversity. Similarly, the U.S. participants, who will represent the Pakistanis U.S. media hosts during the

internships, will go to Pakistan for two-week programs during which they will learn the realities of

Pakistani journalism and national life through site visits, interviews and opportunities to interact with

journalists, officials and ordinary Pakistanis.

Participants on both sides will have opportunities to report on their experiences in each country, which will

help to educate their audiences and dispel myths and misperceptions that people carry in each country

about residents of the other. ICFJ will carry out the Pakistan-based activities with the assistance of a local

Pakistani journalism organization, and the University of MarylandsPhilip Merrill College of Journalism will

assist the U.S. activities.

[15]

Regulation[edit]

History[edit]

The first step in introducing media laws in the country was done by the then military ruler and

President Ayub Khan who promulgated the Press and Publication Ordinance (PPO) in 1962. The law

empowered the authorities to confiscate newspapers, close down news providers, and arrest journalists.

Using these laws, Ayub Khan nationalised large parts of the press and took over one of the two largest

news agencies. The other agencies was pushed into severe crisis and had to seek financial support from

the government. Pakistani Radio and Television, which was established in 1964 was also brought under

the strict control of the government.

More draconian additions were made to the PPO during the reign of General Zia-Ul-Haq in the 1980s.

According to these new amendments, the publisher would be liable and prosecuted if a story was not to

the liking of the administration even if it was factual and of national interest. These amendments were

used to promote Haq's Islamist leanings and demonstrated the alliance between the military and religions

leaders. Censorship during the Zia years was direct, concrete and dictatorial. Newspapers were

scrutinised; critical or undesired sections of an article censored. In the wake of Zia-ul-Haq's sudden death

and the return of democracy, the way was paved to abate the draconian media laws through a revision of

media legislation called the Revised PPO (RPPO).

From 2002, under General Pervez Musharraf, the Pakistani media faced a decisive development that

would lead to a boom in Pakistani electronic media and paved the way to it gaining political clout. New

liberal media laws broke the state's monopoly on the electronic media. TV broadcasting and FM radio

licenses were issued to private media outlets.

The military's motivation for liberalising media licensing was based on an assumption that the Pakistani

media could be used to strengthen national security and counter any perceived threats from India. What

prompted this shift was the military's experience during the two past confrontations with India. One was

the Kargil War and the other was the hijacking of the India Airliner by militants. In both these instances,

the Pakistani military was left with no options to reciprocate because its electronic media were inferior to

that of the Indian media. Better electronic media capacity was needed in the future and thus the market

for electronic media was liberalised.

The justification was just as much a desire to counter the Indian media power, as it was a wish to set the

media "free" with the rights that electronic media had in liberal, open societies. The military thought it

could still control the media and harness it if it strayed from what the regime believed was in the national

interest - and in accordance with its own political agenda.

This assessment however proved to be wrong as the media and in particular the new many new TV

channels became a powerful force in civil society. The media became an important actor in the process

that led to fall of Musharraf and his regime. By providing extensive coverage of the 2007 Lawyer's

Movement's struggle to get the chief justice reinstated, the media played a significant role in mobilising

civil society. This protest movement, with millions of Pakistanis taking to the streets in the name of having

an independent judiciary and democratic rule, left Musharraf with little backing from civil society and the

army. Ultimately, he had to call for elections. Recently, due to a renewed interplay between civil society

organisations, the Lawyers' Movement and the electronic media, Pakistan's new President, Asif Ali

Zardari had to give in to public and political pressure and reinstate the chief justice. The emergence of

powerful civil society actors was unprecedented inPakistani history. These could not have gained in

strength without the media, which will need to continue and play a pivotal role if Pakistan has to develop a

stronger democracy, greater stability and take on socio-political reforms.

Whether Pakistan's media, with its powerful TV channels, is able to take on such a huge responsibility

and make changes from within depends on improving general working conditions; on the military and the

state bureaucracy; the security situation of journalists; media laws revision; better journalism training; and

lastly on the will of the media and the media owners themselves.

[2]

Legal framework[edit]

Though Pakistani media enjoy relative freedom compared to some of its South Asian neighbours, the

industry was subjected to many undemocratic and regressive laws and regulations. The country was

subjected to alternating military and democratic rule - but has managed to thrive on basic democratic

norms. Though the Pakistani media had to work under mimlitary dictatorships and repressive regimes,

which instituted many restrictive laws and regulations for media in order to 'control' it, the media was not

largely affected. The laws are, however, detrimental to democracy reform, and represent a potential

threat to the future of Pakistan and democracy.

[2]

Constitution[edit]

The Pakistani Constitution upholds the fundamentals for a vibrant democracy and guarantees freedom of

expression and the basic premise for media freedom. While emphasising the state's allegiance to Islam,

the constitution underlines the key civil rights inherent in a democracy and states that citizens:

Shall be guaranteed fundamental rights, including equality of status, of opportunity and

before law, social, economic and political justice, and freedom of thought, expression, belief,

faith, worship and association, subject to law and public morality.

However, the constitution and democratic governance in Pakistan was repeatedly set out of play by

military coups and the country was under military dictatorship for more than half its existence. Thus basic

- if not all - democratic norms were severely affected, but the country managed to survive through these

dark periods and reinstate its sidelined socio-political values. The media played a crucial role in this

process.

Even in the darkest days of the worst kind of military rule, it has been the Pakistani media

that had kept the hope for the country and its future alive. No other institution in the country,

neither the political parties nor the civil society, not even the judiciary could make such a

claim. When every other door had been shuttered, it had been the media and media alone

that had crashed open alternatives for the willing to come out and take on the worst dictator.

M Ziauddin, media law activist associated with Internews.

Media laws[edit]

There are a number of legislative and regulatory mechanisms that directly and indirectly affect the media.

Besides the Press and Publication Ordinance (PPO) mentioned, these laws include the Printing Presses

and Publications Ordinance 1988, the Freedom of Information Ordinance of 2002, the Pakistan Electronic

Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) of 2002, the Defamation Ordinance of 2002, the Contempt of Court

Ordinance of 2003, the Press, Newspapers, News Agencies and Books Registration Ordinance 2003, the

Press Council Ordinance 2002, the Intellectual Property Organisation of Pakistan Ordinance 2005 and

lastly the Access to Information Ordinance of 2006. Also there were attempts in 2006 for further

legislation ostensibly "to streamline registration of newspapers, periodicals, news and advertising

agencies and authentication of circulation figures of newspapers and periodicals (PAPRA)."

The liberalisation of the electronic media in 2002 was coupled to a bulk of regulations. The opening of the

media market led to the mushrooming of satellite channels in Pakistan. Many operators started satellite

and/or cable TV outlets without any supervision by the authorities. The government felt that it was losing

millions of rupees by not 'regulating' the mushrooming cable TV business.

Another consequence of the 2002 regulations was that most of these were hurriedly enacted by

President Musharraf before the new government took office. Most of the new laws that were anti-

democratic and were not intended to promote public activism but to increase his control of the public.

Many media activists felt that the new regulations were opaque and had been subject to interpretation by

the courts which would have provided media practitioners with clearer guidelines.

[2]

Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority[edit]

Main article: Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority

The Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA, formerly RAMBO - Regulatory Authority for

Media and Broadcast Organizations) was formed in 2002 to "facilitate and promote a free, fair and

independent electronic media", including opening the broadcasting market in Pakistan.

[16]

By the end of

2009 PEMRA had:

[17]

issued 78 satellite TV licenses;

issued "landing rights" to 28 TV channels operating from abroad, with more under consideration;

issued licenses for 129 FM radio stations, including 18 non-commercial licenses to leading

universities offering courses mass communication and six licenses in Azad Jammu and Kashmir;

registered 2,346 cable TV systems serving an estimated 8 million households; and

issued six MMDS (Multichannel Multipoint Distribution Service), two Internet protocol TV (IPTV), and

two mobile TV licenses, with more under consideration.

PEMRA is also involved in media censorship and occasionally halts broadcasts and closes media outlets.

Publication or broadcast of anything which defames or brings into ridicule the head of state, or members

of the armed forces, or executive, legislative or judicial organs of the state, as well as any broadcasts

deemed to be false or baseless can bring jail terms of up to three years, fines of up to 10 million rupees

(US$165,000), and license cancellation. In practice, these rules and regulations are not enforced.

[18]

On November 2011, Pakistani cable television operators blocked the BBC World News TV channel after it

broadcast a documentary, entitled Secret Pakistan.

[19]

However, Pakistanis with a dish receiver can still

watch it and can continue to access its website and web stream. Dr. Moeed Pirzada of PTV stated that it

was hypocritical of the foreign media to label it as 'suppression of the media' when the United States

continues to ban Al Jazeera English and no cable operator in the US would carry the channel. He also

stated that even 'democratic' and 'liberal' Indians refuse to carry a single Pakistani news channel on their

cable or any Pakistani op-ed writers in their newspapers.

[20]

Television[edit]

Main article: Television in Pakistan

Further information: List of Urdu language television channels

The first television station began broadcasting from Lahore in 26 November 1964. Television in Pakistan

remained the government's exclusive control until 1990 when Shalimar Television Network (STN) and

Network Television Marketing (NTM) launched Pakistans first private TV channel. Foreign satellite TV

channels were added during the 1990s.

[17]

Traditionally, the government-owned Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV) has been the dominant

media player in Pakistan. The PTV channels are controlled by the government and opposition views are

not given much time. The past decade has seen the emergence of several private TV channels showing

news and entertainment, such as GEO TV, AAJ TV, ARY Digital, HUM, MTV Pakistan, and others.

Traditionally the bulk of TV shows have been plays or soap operas, some of them critically acclaimed.

Various American, European, Asian TV channels, and movies are available to a majority of the population

via Cable TV.

[citation needed]

Television accounted for almost half of the advertising expenditure in Pakistan in

2002.

[21][dead link]

Radio[edit]

Main article: Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation

See also: List of Pakistani radio channels

The government-owned Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation (PBC) was formed on 14 August 1947, the

day of Pakistani independence. It was a direct descendant of the Indian Broadcasting Company, which

later became All India Radio. At independence, Pakistan had radio stations in Dhaka, Lahore,

and Peshawar. A major programme of expansion saw new stations open at Karachiand Rawalpindi in

1948, and a new broadcasting house at Karachi in 1950. This was followed by new radio stations

at Hyderabad (1951), Quetta (1956), a second station at Rawalpindi (1960), and a receiving centre at

Peshawar (1960). During the 1980s and 1990s the corporation expanded its network to many cities and

towns of Pakistan to provide greater service to the local people. In October 1998, Radio Pakistan started

its first FM transmission.

[17]

Today, there are over a hundred public and private radio stations due to more liberal media regulations.

FM broadcast licenses are awarded to parties that commit to open FM broadcasting stations in at least

one rural city along with the major city of their choice.

The press is much more restricted in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), where independent

radio is allowed only with permission from the government.

[18]

Cinema[edit]

Main article: Cinema of Pakistan

See also: List of Pakistani films, Lollywood, Pollywood, Kariwood, Kara Film Festival, and Cinepax

In the golden days of Pakistani cinema, the film industry churned out more than 200 films

annually, today its one-fifth of what it used to be. The Federal Bureau of Statistics shows

that once the country boasted at least 700 cinemas, this number has dwindled to less than

170 by 2005.

[22]

The indigenous movie industry, based in Lahore and known as "Lollywood", produces roughly forty

feature-length films a year.

[citation needed]

In 2008 the Pakistani government partially lifted its 42-year ban on screening Indian movies in

Pakistan.

[23]

Newspapers and magazines[edit]

Further information: List of newspapers in Pakistan and List of magazines in Pakistan

In 1947 only four major Muslim-owned newspapers existed in the area now called Pakistan: Pakistan

Times, Zamindar, Nawa-i-Waqt, and Civil and Military Gazette. A number of Muslim papers moved to

Pakistan, including Dawn, which began publishing daily in Karachi in 1947, the Morning News, and the

Urdu-language dailies Jang and Anjam. By the early 2000s, 1,500 newspapers and journals existed in

Pakistan.

[24]

In the early 21st century, as in the rest of the world, the number of print outlets in Pakistan declined

precipitously, but total circulation numbers increased.

[citation needed]

From 1994 to 1997, the total number of

daily, monthly, and other publications increased from 3,242 to 4,455, but had dropped to just 945 by 2003

with most of the decline occurring in the Punjab Province. However, from 1994 to 2003 total print

circulation increased substantially, particularly for dailies (3 million to 6.2 million). And after the low point

in 2003 the number of publications grew to 1279 in 2004, to 1997 in 2005, 1467 in 2006, 1820 in 2007,

and 1199 in 2008.

[25]

Newspapers and magazines are published in 11 languages; most in Urdu and Sindhi, but English-

language publications are numerous.

[citation needed]

Most print media are privately owned, but the

government controls the Associated Press of Pakistan, one of the major news agencies. From 1964 into

the early 1990s, the National Press Trust acted as the government's front to control the press. The state,

however, no longer publishes daily newspapers; the former Press Trust sold or liquidated its newspapers

and magazines in the early 1990s.

[24]

The press is generally free and has played an active role in national elections, but journalists often

exercise self-censorship as a result of arrests and intimidation by government and societal actors. The

press is much more restricted in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), where no newspapers

are published, and in Azad Kashmir, where publications need special permission from the regional

government to operate and pro-independence publications are generally prohibited.

[18]

News Agencies[edit]

Press Council and Newspaper Regulation[edit]

Prior to 2002, News Agencies in Pakistan were completely unregulated. Established under the Press

Council of Pakistan Ordinance in October 2002, the body operates on a semi-autonomous nature along

with an Ethical Code of Practice signed by President Musharraf. It is mandated with multi-faceted tasks

that range from protection of press freedom to regulatory mechanisms and review of complaints from the

public.

However, the Press Council never came into operation due to the reservations of the media

organisations. In protest over its establishment, the professional journalists organisations refrained from

nominating their four members to the Council. Nevertheless, the chairman was appointed, offices now

exist and general administration work continues. This has led the government to review the entire Press

Council mechanism.

The Press Council Ordinance has a direct link to the Press, Newspapers, News Agencies and Books

Registration Ordinance (PNNABRO) of 2002. This legislation deals with procedures for registration of

publications of criteria of media ownerships.

Among the documents required for the permit or 'Declaration' for publishing a newspaper is a guarantee

from the editor to abide by the Ethical Code of Practice contained in the Schedule to the Press Council of

Pakistan Ordinance. Though the Press Council procedure has made silenced or paralysed, these forms

of interlinking laws could provide the government with additional means for imposing restrictions and take

draconian actions against newspapers. The PNNABRO, among many other requirements demands that a

publisher provides his bank details. It also has strict controls and regulations for the registering

procedure. It not only demands logistical details, but also requires detailed information on editors and

content providers.

Ownership of publications (mainly newspapers and news agencies) is restricted to Pakistani nationals if

special government permission is not given. In partnerships, foreign involvement cannot exceed 25

percent. The law does not permit foreigners to obtain a 'Declaration' to run a news agency or any media

station.

[2]

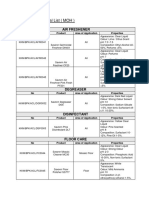

Pakistan's major news agencies include:

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- MaslaDokument2 SeitenMaslaMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journalism & Mass Communication: Part-IiDokument1 SeiteJournalism & Mass Communication: Part-IiMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stages of Science FinalDokument7 SeitenStages of Science FinalMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abortion BMJDokument3 SeitenAbortion BMJMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ø G) T B Èe L M W Ä ZZ À Ñ A C ZZ Gâ J 1 C P V # Ö Å Š) G ÷ Ø G) y Æ V Y W B $+ W G Ì ÷ Z K Å Ƒ Ü U Š K, 7, #Dokument4 SeitenØ G) T B Èe L M W Ä ZZ À Ñ A C ZZ Gâ J 1 C P V # Ö Å Š) G ÷ Ø G) y Æ V Y W B $+ W G Ì ÷ Z K Å Ƒ Ü U Š K, 7, #Mir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Media & Terrorism: The Power of PropagationDokument25 SeitenMedia & Terrorism: The Power of PropagationMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture To Technology: by Neil Postman (New York: Vintage Books, 1993, $11.00)Dokument3 SeitenTechnopoly: The Surrender of Culture To Technology: by Neil Postman (New York: Vintage Books, 1993, $11.00)Mir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Knowledge McqsDokument186 SeitenGeneral Knowledge McqsMir Ahmad Feroz83% (6)

- Media and Political CommunicationDokument13 SeitenMedia and Political CommunicationMir Ahmad Feroz100% (1)

- How Pakistani and The US Elite Print Media Painted Issue of Drone Attacks Framing Analysis of The News International and The New York TimesDokument17 SeitenHow Pakistani and The US Elite Print Media Painted Issue of Drone Attacks Framing Analysis of The News International and The New York TimesMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Functional English: 1-A) B) Give ONE-WORD For Any FIVE of The FollowingDokument2 SeitenFunctional English: 1-A) B) Give ONE-WORD For Any FIVE of The FollowingMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bal e JibrilDokument9 SeitenBal e JibrilMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2nd Year Objecive FinalDokument1 Seite2nd Year Objecive FinalMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Year Bastion College of Science & Commerce ObjectiveDokument2 Seiten2 Year Bastion College of Science & Commerce ObjectiveMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 - Functional EnglishDokument2 Seiten3 - Functional EnglishMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding and Evaluating Mass Communication TheoryDokument1 SeiteUnderstanding and Evaluating Mass Communication TheoryMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Chronology of Key EventsDokument5 SeitenA Chronology of Key EventsMir Ahmad FerozNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Professional Experience Report - Edu70012Dokument11 SeitenProfessional Experience Report - Edu70012api-466552053Noch keine Bewertungen

- Becoming FarmersDokument13 SeitenBecoming FarmersJimena RoblesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Need You Now Lyrics: Charles Scott, HillaryDokument3 SeitenNeed You Now Lyrics: Charles Scott, HillaryAl UsadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Time Interest Earned RatioDokument40 SeitenTime Interest Earned RatioFarihaFardeenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approved Chemical ListDokument2 SeitenApproved Chemical ListSyed Mansur Alyahya100% (1)

- Acts 1 Bible StudyDokument4 SeitenActs 1 Bible StudyPastor Jeanne100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Pumpkin Moon SandDokument3 SeitenLesson Plan Pumpkin Moon Sandapi-273177086Noch keine Bewertungen

- Design Thinking PDFDokument7 SeitenDesign Thinking PDFFernan SantosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Wallace Stevens - by Marianne Moore - The New York Review of BooksDokument2 SeitenOn Wallace Stevens - by Marianne Moore - The New York Review of BooksTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Questions Operational Excellence? Software WorksDokument6 SeitenReview Questions Operational Excellence? Software WorksDwi RizkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1stQ Week5Dokument3 Seiten1stQ Week5Jesse QuingaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9m.2-L.5@i Have A Dream & Literary DevicesDokument2 Seiten9m.2-L.5@i Have A Dream & Literary DevicesMaria BuizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sukhtankar Vaishnav Corruption IPF - Full PDFDokument79 SeitenSukhtankar Vaishnav Corruption IPF - Full PDFNikita anandNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Berenstain Bears and Baby Makes FiveDokument33 SeitenThe Berenstain Bears and Baby Makes Fivezhuqiming87% (54)

- The Changeling by Thomas MiddletonDokument47 SeitenThe Changeling by Thomas MiddletonPaulinaOdeth RothNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blunders and How To Avoid Them Dunnington PDFDokument147 SeitenBlunders and How To Avoid Them Dunnington PDFrajveer404100% (2)

- Serological and Molecular DiagnosisDokument9 SeitenSerological and Molecular DiagnosisPAIRAT, Ella Joy M.Noch keine Bewertungen

- 011 - Descriptive Writing - UpdatedDokument39 Seiten011 - Descriptive Writing - UpdatedLeroy ChengNoch keine Bewertungen

- Core ApiDokument27 SeitenCore ApiAnderson Soares AraujoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apache Hive Essentials 2nd PDFDokument204 SeitenApache Hive Essentials 2nd PDFketanmehta4u0% (1)

- A Study of Consumer Behavior in Real Estate Sector: Inderpreet SinghDokument17 SeitenA Study of Consumer Behavior in Real Estate Sector: Inderpreet SinghMahesh KhadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- GRADE 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG: TLE6AG-Oc-3-1.3.3Dokument7 SeitenGRADE 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG: TLE6AG-Oc-3-1.3.3Roxanne Pia FlorentinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mezbah Uddin Ahmed (173-017-054) Chapter 11Dokument12 SeitenMezbah Uddin Ahmed (173-017-054) Chapter 11riftNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unified Power Quality Conditioner (Upqc) With Pi and Hysteresis Controller For Power Quality Improvement in Distribution SystemsDokument7 SeitenUnified Power Quality Conditioner (Upqc) With Pi and Hysteresis Controller For Power Quality Improvement in Distribution SystemsKANNAN MANINoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of Numbers: SeriesDokument13 SeitenTypes of Numbers: SeriesAnonymous NhQAPh5toNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tugas Conditional Sentences YanneDokument3 SeitenTugas Conditional Sentences Yanneyanne nurmalitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay EnglishDokument4 SeitenEssay Englishkiera.kassellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activity Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenActivity Lesson PlanPsiho LoguseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lite Touch. Completo PDFDokument206 SeitenLite Touch. Completo PDFkerlystefaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageDokument11 SeitenChildbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageWenny Indah Purnama Eka SariNoch keine Bewertungen