Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Practicality in Dmitri Tymoczko

Hochgeladen von

mattsiebergCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Practicality in Dmitri Tymoczko

Hochgeladen von

mattsiebergCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Practicality in Dmitri Tymoczko's Graphs

Today's music industry is made up, for the most part, by performers, composers and non-

musicians who deal with managerial aspects of what the rest of them require !usic theorists

ha"e the #oy of disco"ery what the others seems to o"erlook, not that it is any consequence of

laziness or obli"ion but rather that their area of e$pertise doesn't apply the insistent demand

for the music's e$istence % draw a thin line between composers and theorists partly because of

how they are percei"ed by the rest of the industry, most ob"iously by their output, not in the

amount but who their output reaches & composer's finished product can be heard by anyone

#ust as a theorists product can be e$amined by anyone 'f course, the aural element is much

more palatable to a wider audience than understanding a gamut of foreign equations and

terminology

"..it is possible that with extensive training ordinary listeners can sensitize themselves to the

sequences structure.."

Dmitri Tymoczko is one of those indi"iduals who has dug deep to disco"er new formations

(eing able to defending what composers ha"e gi"en us is an integral part of composing and

performing !usic of the future is influenced by studying music of the past %n Tymoczko's

research the details go far to #ustify his ideas but to often these ideas seem to be e$aggerated

%'m in no intellectual position to brush off Tymoczko's findings on grounds that there are too

many e$ceptions or that details don't matter !y hope is that by applying these tactics to some

familiar pieces in my standard repertoire % can better understand the conte$t of where his

constraints and graphs can impro"e my understanding of a musical genre, set of works or )at

the "ery least* an indi"idual piece of music

&s Tymoczko leads us through a redisco"ery of what is already known he first presents a

powerful statement whose only purpose is to completely confuse us, then he has the

opportunity to slowly rebuilding the concept %n our state of ignorance e$amples are pulled

from many different breeds, such as his reference of a +lementi sonata and some Debussy

when detailing his 'PT%+ system ,e are in no position to slow our rebuilding process by

questioning the significance of his methods and how they relate to the entire collection of

those composers' music The e$amples compliment his current argument well but may pro"e

unable to stand up to their claims when more is to be pro"ed

,e are taken through a maze of models and instances of the 'PT%+ application and its

importance of simplifying chords we encounter The pitch-class philosophy is not a comple$

item to iterate The lengths he goes to spell out the different ways to interpret distance seems

wasteful -uckily, if in the earlier chapters of his book % ha"e missed the boat captained by

Dmitri at least % ha"e his pardon .it is possible to understand the gist of later chapters e"en

while remaining somewhat fuzzy about the technical material in +hapters /01.

Pitch 2pace "s Pitch-+lass

3oice -eading is taken to a whole new le"el by Tymoczko &gain, the process remains the

same while our understanding of it is o"ershadowed by the elaborate attempt at e$posing new

ideas Trained musicians can already see these chordal relationships that the 'PT%+ system

represents 'ur theory 454 courses con"eyed "oice leading well enough to trust (ach,

+lementi, 6aydn and !ozart &s we witness in the following century we can see a slow

progression of creati"ity and risk taking of 47th century composers ,e had music that

foreshadowed ,agner such as the e$perimentation by (eetho"en in his late career, ,eber and

-iszt Tymoczko's "oice leading theories are so forgi"ing in that they allow a melody to

#ustify any harmonic progression %t's hard to conceptualize a ma#or chord being anything

more than ma#or Tymoczko lays out e"er relationship between standard chords in terms of

semi-tones and then retraces his steps claiming that more is to be seen in between the

notes The pitch-class system ultimately remo"es one problem we encounter when condensing

a chord for the purpose of identifying it8 which pitch will be the constant as the other "oices

are mo"ed to an appropriate octa"e within a 4/ semi-tone space near the constant note -arger

gaps within the newly arranged chord can be quickly eliminated by repositioning notes, one at

a time, from one end of the chord to the other until the smallest number of semitones e$ists

The same can be done to the neighboring chords to see if the "oice-leading is effecti"e

"Thus when we say that an object is a major chord, we are neglecting an enormous number of

musical details, leaving behind something that is very abstractan ordered sequence of

cloc!wise distances around the pitch" class circle.#

The phrase .chord progression. seems to be equi"alent to cursing when Tymoczko uses it 6is

portrayal is that we don't see the mo"ement in the "oices from chord to chord 6is pitch-class

wheel does present a new "isual for following a particular "oice but forces us to completely

turn off our ears !usicians using the pitch-class system )that has already been set place by

pre"ious theorists, like 6oward 6ansen* know to use it only for brief isolation of a "oices

path Tymoczko's pitch space graph )or line* is less in"asi"e to our sensiti"ity toward "oice

motion 6ere there is an equally as simply layout with a "oice's path easy to distinct from its

colleagues 6is wording is so bold that you'd think he is defending a new standard for

notation ,e'"e always been able to mo"e from chord to chord in multiple ways, is he really

the first one to point out the shortest path9 :o one wishes to use a pitch system that forces us

to ignore "oice leading and settle for a .tunnel "ision. approach to chord analysis %n the case

of most other theories there is no need to lea"e out a reference to pitch on some sort of

"ertical gauge unless eliminating doubling on the staff pro"es to be far too cumbersome -

2piral piano

(ut back to the 'PT%+ system; Tonal music illustrates a state of aural homeostasis8 adhere

to the guidelines and you'll fit right in The procedures e$plained in $ %eometry of &usic are

quite broad 2o often Tymoczko walks us through a chord to chord modification showing our

current staff notation side-by-side to the graphs of the newly introduced pitch space and pitch-

class systems and then halts the discussion before relating any con"incing element of science

This book is all about using the math to #ustify "oice-leading paths but there is a significant

lack of mathematical equations The application of a combination of permutation, in"ersions

and the others operations can create endless potential in harmonic progression but the details

are missing that should include specific equations for creating the desired mo"ement

Tymoczko anticipated public connection to his book would be much impro"ed if a companion

manual containing these equations e$isted %t is unclear where the math and science are

in"ol"ed in the 'PT%+ symmetries

Tymoczko insinuates that "oice leading is incorrectly taught in regard to the size of the "oice-

leading %n a search for <reasonable= "oice-leading we naturally consider the distance between

all of the "oice motion and a consistent path for each "oice to follow 2ection /> of his book

encourages ha"ing a field day with "oice crossing !ore limitation should be enforced on this

topic for the sake of following "oices as we analyze multiple "oices together and for our ear

to capture the motion ,here possible, only two "oices leaping distances greater than a ma#or

third and any "oice crossing does not appear but a single instance per stationary chord as to

not disrupt an attenti"e listener )<stationary= is referring to a chord that is blocked or "ertical

as opposed to arpeggios in the harmonic structure* ?or instance, Tymoczko could recommend

for his readers to reser"e "oice leaping by more than a third to one distinct "oice that, more or

less, takes the role as a melody and the other "oice being the bass )assuming the style requires

the lowest "oice to pro"ide the root of the chord for the ma#ority of the time with the

e$ception of in"ersions* 6ere Tymoczko has an opportunity to demonstrate efficient "oice-

leading on his pitch-class <a$is of symmetry= and alongside it a staff containing a single clef

and the notes of the chord condensed within one octa"e %t seems that in a constant search for

a suitable "oice leading the first step should be disco"ering the absolute smallest path that all

of the "oices could follow collecti"ely and de"iating from it for the "oices that require greater

leaps The smallest series of "oice leading represents the constant that a science e$periment

would contain and remains in the shadow of the chord as reference

& topic that refuses to permeate my skull is the issue of di"iding the octa"e e"enly

Tymoczko@s tables poorly assist his in deli"ering his argument A"en and nearly e"en

di"isions distract from his ultimate point of why chords sound good &s found on the

Princeton music course website, Tymoczko@s 1

th

handout "ery basically e$plains the theory of

how the octa"e is di"ided e"enlyB

'The mathematical reason for this is slightly complicated. (ts related to the fact that, when

we thin! in terms of fundamental frequencies, the perfect fifth and the major triad divide the

octave exactly evenly) the note **+ ,z -./0 divides the octave between 11+ ,z -$*0 and //+

,z -$/0 into two equal -22+",z"sized0 parts. -3ote that ./ is a perfect fifth above $/.0

4imilarly, the $ major triad **+ ,z -./0, //+ ,z -$/0, and 55+ ,z -6s50 divides the octave

between **+ ,z -./0 and 77+ ,z -.50 into three equal -22+",z"sized pieces0. (t turns out that

when we go from fundamental frequencies to ordinary note labels, we transform perfectly

even divisions into nearly even divisions.#

%t@s good to know he is able to lay it out in a simple manner for his students &ctually, it is

comical how in his book chapter three seems to unfold smoothly lea"ing some readers

completely bewildered and feeling ignorant and then warns his freshmen class how

intellectual one must be to understand such theories but coddles them with an easy

e$planation of 6z di"ision The problems start when this theory is tested on an equal

tempered instrument with twel"e pitches and then looking at how the octa"e is di"ided on the

staff (y comparing wa"e length and our diatonic scale system we are decei"ed %n fact, when

understood through this process, augmented chords become the nearly e"en triads and ma#or

triads are perfectly e"en This makes more sense on paper before applying it to an instrument

%n the three dimensional chord theory, this replaces the augmented cubes with ma#or cubes

(y di"iding the scale like Tymoczko we ha"e not created greater or fewer possibilities for

harmonic progression but #ust changed where the central a$is appears 6e prefers the method

in his book because it applies so fairly to the (rahms Piano Cuartet he presents %f my

suggestions were e$plored the outer limits of the three dimensional tiles would be well suited

for the baroque and classical styles

%f ma#or chords act as the focal point then this three-dimensional space would translate easily

into representing mo"ement between scales )more appropriately modes* &s we mo"e from

the cube that represents the + ma#or scale one note is altered There are si$ options closely

related to the scale and then three for the one following %f working with baroque or classical

styles few scales will be utilized but, as Tymoczko e$plains, (rahms, 2hostako"ich and

Debussy will use many e$otic scales :o matter the way the octa"e is di"ided, chords with

doubled notes will still be found on the walls of the diagram, strongly suggesting that the

piece of music at hand is not tonal %f a composer were applying this system to a new piece of

music written in the late romantic style he would find it useful in finding desired "oice

leading on a chord-to-chord basis or at most the motion o"er a small phrase

% appreciate math@s presence in music and % use it as often as needed The circle of fifths is an

in"aluable tool for training and reading music by referencing the distance from one note to the

ne$t rather than resetting the brain for e"ery change The significance of using small distances

for "oice leading and harmonic progression is reawakened by the in-depth application of

Tymoczko@s symmetries (y bewildering and then con"incing the reader that these findings

are original encourages more credit than is due Pitch space and three-dimensional diagrams

assist in the redisco"ery of what we already ha"e understood ,ith the help of other theorists

such as Dulian 6ook

not enough math A$cuses it as science

Dulian 6ook, Eoger 2cruton

'riginal but e$aggerated

Ee"iew of Dmitri Tymoczko, & Geometry of !usicB 6armony and +ounterpoint in the

A$tended +ommon Practice )'$ford Fni"ersity Press, /544*

Dulian 6ook

httpBGGwwwmtosmtorgGissuesGmto444>HGmto444>Hhookhtml

Dmitri Tymoczko -6andouts 1 and /5

httpBGGdmitrimycpanelprincetoneduGfilesGpdfsG!F245Ihandoutspdf

2cruton The 2pace of !usic / review of The Geometry of !usic httpBGGwwwroger-

scrutoncomGwork-in-progressG47-booksGJ7-the-space-of-musichtml

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Jesus Tender:At Evening - Cotter - DDokument3 SeitenJesus Tender:At Evening - Cotter - DmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angels We Have Heard On High - He Is Born - GDokument6 SeitenAngels We Have Heard On High - He Is Born - GmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Homecoming Formation PDFDokument3 SeitenHomecoming Formation PDFmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dream ValleyDokument2 SeitenDream ValleymattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- God Bless AmericaDokument2 SeitenGod Bless Americamattsieberg100% (5)

- Come To Us Emmanuel - Comfort My People - F-EDokument4 SeitenCome To Us Emmanuel - Comfort My People - F-EmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Once You UploadDokument13 SeitenOnce You UploadmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daily ScheduleDokument3 SeitenDaily SchedulemattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- God Bless AmericaDokument2 SeitenGod Bless Americamattsieberg100% (5)

- World Drumming - Caribbean Map PDFDokument2 SeitenWorld Drumming - Caribbean Map PDFmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daily Schedule PDFDokument1 SeiteDaily Schedule PDFmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attinata: Ruggiero LeoncavalloDokument6 SeitenAttinata: Ruggiero LeoncavalloMatheus Provin100% (1)

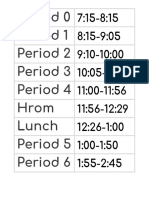

- Period 0 Period 1 Period 2 Period 3 Period 4 Hrom Lunch Period 5 Period 6Dokument1 SeitePeriod 0 Period 1 Period 2 Period 3 Period 4 Hrom Lunch Period 5 Period 6mattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sunday: Camp Info NCAA EligibilityDokument1 SeiteSunday: Camp Info NCAA EligibilitymattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spring Concert Tees 2018Dokument7 SeitenSpring Concert Tees 2018mattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- G Major Scale PDFDokument1 SeiteG Major Scale PDFmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- As The Deer:Celtic GraceDokument3 SeitenAs The Deer:Celtic GracemattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bells Praise To The LordDokument4 SeitenBells Praise To The LordmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preview of "Lg-176919923"Dokument2 SeitenPreview of "Lg-176919923"mattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonnymoon For TwoDokument8 SeitenSonnymoon For Twomattsieberg100% (1)

- They Dont Drum Pad PDFDokument1 SeiteThey Dont Drum Pad PDFmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- They Don't Realy Care About Us: Drum PadDokument1 SeiteThey Don't Realy Care About Us: Drum PadmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Drumming - Caribbean MapDokument2 SeitenWorld Drumming - Caribbean MapmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2nd & 7th PDFDokument1 Seite2nd & 7th PDFmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Serialism U2013 Matthew SiebergDokument6 SeitenSerialism U2013 Matthew SiebergmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- BeethovenDokument2 SeitenBeethovenmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Romantic SonataDokument5 SeitenThe Romantic SonatamattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scales in 3 StepsDokument1 SeiteScales in 3 StepsmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Its Not UnusualDokument5 SeitenIts Not Unusualmattsieberg100% (4)

- 8am Final GroupsDokument1 Seite8am Final GroupsmattsiebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Design and Implementation of A Computerised Stadium Management Information SystemDokument33 SeitenDesign and Implementation of A Computerised Stadium Management Information SystemBabatunde Ajibola TaofeekNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 Fall TSJ s03 The Mystery of The Gospel PT 1 - Stuart GreavesDokument5 Seiten2012 Fall TSJ s03 The Mystery of The Gospel PT 1 - Stuart Greavesapi-164301844Noch keine Bewertungen

- Group5 (Legit) - Brain Base-Curriculum-InnovationsDokument6 SeitenGroup5 (Legit) - Brain Base-Curriculum-InnovationsTiffany InocenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hallux Valgus SXDokument569 SeitenHallux Valgus SXandi100% (2)

- Where The Boys Are (Verbs) : Name Oscar Oreste Salvador Carlos Date PeriodDokument6 SeitenWhere The Boys Are (Verbs) : Name Oscar Oreste Salvador Carlos Date PeriodOscar Oreste Salvador CarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eris User ManualDokument8 SeitenEris User ManualcasaleiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Mile.: # Speed Last Race # Prime Power # Class Rating # Best Speed at DistDokument5 Seiten1 Mile.: # Speed Last Race # Prime Power # Class Rating # Best Speed at DistNick RamboNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08.08.2022 FinalDokument4 Seiten08.08.2022 Finalniezhe152Noch keine Bewertungen

- CT, PT, IVT, Current Transformer, Potential Transformer, Distribution Boxes, LT Distribution BoxesDokument2 SeitenCT, PT, IVT, Current Transformer, Potential Transformer, Distribution Boxes, LT Distribution BoxesSharafatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gaffney S Business ContactsDokument6 SeitenGaffney S Business ContactsSara Mitchell Mitchell100% (1)

- Listen The Song and Order The LyricsDokument6 SeitenListen The Song and Order The LyricsE-Eliseo Surum-iNoch keine Bewertungen

- 100 Demon WeaponsDokument31 Seiten100 Demon WeaponsSpencer KrigbaumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Superhero Photoshop Lesson PlanDokument4 SeitenSuperhero Photoshop Lesson Planapi-243788225Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hse Check List For Portable Grinding MachineDokument1 SeiteHse Check List For Portable Grinding MachineMD AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide To Tanzania Taxation SystemDokument3 SeitenGuide To Tanzania Taxation Systemhima100% (1)

- Project Presentation (142311004) FinalDokument60 SeitenProject Presentation (142311004) FinalSaad AhammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Guidelines For Processing Operations Hydrocarbons VQDokument47 SeitenAssessment Guidelines For Processing Operations Hydrocarbons VQMatthewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letters of Travell by George SandDokument332 SeitenLetters of Travell by George SandRocío Medina100% (2)

- Kangar 1 31/12/21Dokument4 SeitenKangar 1 31/12/21TENGKU IRSALINA SYAHIRAH BINTI TENGKU MUHAIRI KTNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 - Practice QuestionsDokument2 SeitenChapter 2 - Practice QuestionsSiddhant AggarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leaving Europe For Hong Kong and Manila and Exile in DapitanDokument17 SeitenLeaving Europe For Hong Kong and Manila and Exile in DapitanPan CorreoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sand Cone Method: Measurement in The FieldDokument2 SeitenSand Cone Method: Measurement in The FieldAbbas tahmasebi poorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philsa International Placement and Services Corporation vs. Secretary of Labor and Employment PDFDokument20 SeitenPhilsa International Placement and Services Corporation vs. Secretary of Labor and Employment PDFKrissaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Menu EngineeringDokument7 SeitenMenu EngineeringVijay KumaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPM Bahasa Inggeris PAPER 1 - NOTES 2020Dokument11 SeitenSPM Bahasa Inggeris PAPER 1 - NOTES 2020MaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unity School of ChristianityDokument3 SeitenUnity School of ChristianityServant Of TruthNoch keine Bewertungen

- 34 The Aby Standard - CoatDokument5 Seiten34 The Aby Standard - CoatMustolih MusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department InvestigationDokument60 SeitenLos Angeles County Sheriff's Department InvestigationBen Harper0% (1)

- V and D ReportDokument3 SeitenV and D ReportkeekumaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cash-Handling Policy: IntentDokument3 SeitenCash-Handling Policy: IntentghaziaNoch keine Bewertungen