Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Lecaroz v. Sandiganbayan

Hochgeladen von

Cari Mangalindan Macaalay100%(1)100% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (1 Abstimmung)

2K Ansichten2 SeitenCase DIgest Law on Public Officers

Originaltitel

Lecaroz v. Sandiganbayan.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCase DIgest Law on Public Officers

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

100%(1)100% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (1 Abstimmung)

2K Ansichten2 SeitenLecaroz v. Sandiganbayan

Hochgeladen von

Cari Mangalindan MacaalayCase DIgest Law on Public Officers

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 2

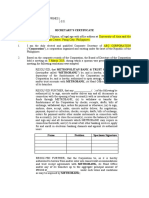

CMM DIGEST

Lecaroz v. Sandiganbayan & People

March 25, 1999

G.R. No. 130872

(The Law on Public Officers, Civil Service Laws, Election Laws)

Petitioner: Francisco & Lenlie Lecaroz

Respondent: Sandiganbayan; People

Ponente: Bellosillo

FACTS:

Francisco Lecaroz (father): Mayor of Santa Cruz, Marinduque.

Lenlie Lecaroz (son): outgoing chairman of Kabataang Barangay (KB) of Santa Cruz & member

of Sangguniang Bayan (SB) representing the federation of KBs.

1985 election of KB: Jowil Red won as Chairman of Barangay Santa Cruz (Lenlie did not run as

candidate as he was no longer qualified, having passed the age limit).

Red was appointed by President Marcos as member of SB of Santa Cruz, representing the

federation of KBs. He received his appointment powers when Aquino was already power.

However, he was not allowed by Mayor Lecaroz to sit as secotral rep in the SB.

Subsequently, Mayor Lecaroz prepared and approved on different dates the payment to

lenlie Lecaros of payrolls covering period of January 1987 to January 1987.

Sandiganbayan: guilty on 13 Informations for Estafa through falsification of Public

Documents.

Red assumed position of KB presidency upon expiration of term of Lenlie Lecaroz.

Thus, when Mayor Lecaroz entered the name of his son in the payroll, he deliberately

stated a falsity.

ISSUE: WON accused are guilty of estafa through falsification? NO.

RATIO:

KB Constitution: In the case of the members of the sanggunian representing the association

of barangay councils and the president of the federation of kabataang barangay, their terms

of office shall be coterminous with their tenure is president of their respective association

and federation.

Theory of accused: Red failed to qualify as KB sectoral representative to the SB since he did

not present an authenticated copy of his appointment papers; neither did he take a valid

oath of office. Resultantly, this enabled petitioner Lenlie Lecaroz to continue as member of

the SB although in a holdover capacity since his term had already expired.

Theory of Sandiganbayan: the holdover provision under Sec. 1 quoted above pertains only to

positions in the KB, clearly implying that since no similar provision is found in Sec. 7 of B.P.

Blg. 51, there can be no holdover with respect to positions in the SB.

SC: Sandiganbayan is incorrect!

The concept of holdover when applied to a public officer implies that the office has a fixed

term and the incumbent is holding onto the succeeding term. It is usually provided by law

that officers elected or appointed for a fixed term shall remain in office not only for that term

but until their successors have been elected and qualified. Where this provision is found, the

office does not become vacant upon the expiration of the term if there is no successor

elected and qualified to assume it, but the present incumbent will carry over until his

successor is elected and qualified, even though it be beyond the term fixed by law.

CMM DIGEST

Lecaroz v. Sandiganbayan & People

March 25, 1999

G.R. No. 130872

(The Law on Public Officers, Civil Service Laws, Election Laws)

In the instant case, although BP Blg. 51 does not say that a Sanggunian member can continue

to occupy his post after the expiration of his term in case his successor fails to qualify, it does

not also say that he is proscribed from holding over. Absent an express or implied

constitutional or statutory provision to the contrary, an officer is entitled to stay in office

until his successor is appointed or chosen and has qualified. The legislative intent of not

allowing holdover must be clearly expressed or at least implied in the legislative enactment,

otherwise it is reasonable to assume that the law-making body favors the same.

Law abhors vacuum in public office: (1) prevent public convenience from suffering; and (2)

avoid hiatus in the performance of govt functions.

(TOPICAL) Reds taking of oath before BP member Reyes in 1985 did not make him validly

assume the presidency of KB.

Under the provisions of the Administrative Code then in force, specifically Sec. 21, Art.

VI thereof, members of the then Batasang Pambansa were not authorized to administer

oaths.

It was only after the approval of RA No. 6733 on 25 July 1989 that members of both

Houses of Congress were vested for the first time with the general authority to

administer oaths. Clearly, under this circumstance, the oath of office taken by Jowil Red

before a member of the Batasang Pambansa who had no authority to administer oaths,

was invalid and amounted to no oath at all.

To be sure, an oath of office is a qualifying requirement for a public office; a prerequisite

to the full investiture with the office. Only when the public officer has satisfied the

prerequisite of oath that his right to enter into the position becomes plenary and

complete. Until then, he has none at all. And for as long as he has not qualified, the

holdover officer is the rightful occupant. It is thus clear in the present case that since

Red never qualified for the post, petitioner Lenlie Lecaroz remained KB representative to

the Sanggunian, albeit in a carry over capacity, and was in every aspect a de jure officer,

or at least a de facto officer entitled to receive the salaries and all the emoluments

appertaining to the position. As such, he could not be considered an intruder and liable

for encroachment of public office.

Accused committed mere judgmental error, without criminal intent or malice. In this case,

there are clear manifestations of good faith and lack of criminal intent. The statements are

not altogether false, considering the doctrine of holdover.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Case Name Topic Case No. - Date Ponente: University of The Philippines College of LawDokument3 SeitenCase Name Topic Case No. - Date Ponente: University of The Philippines College of LawKerriganJamesRoiMaulit100% (1)

- 30 Lecaroz Vs Sandiganbayan DigestDokument2 Seiten30 Lecaroz Vs Sandiganbayan DigestRoby Renna EstoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Luego V CSC DigestDokument2 SeitenLuego V CSC DigestMariano Rentomes100% (2)

- SANGGUNIANG BAYAN OF SAN ANDRES DigestDokument1 SeiteSANGGUNIANG BAYAN OF SAN ANDRES DigestHazel Reyes-AlcantaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest of Tuanda v. An (G.R. No. 110544)Dokument1 SeiteDigest of Tuanda v. An (G.R. No. 110544)Rafael Pangilinan100% (1)

- Torres V RiboDokument1 SeiteTorres V RiboJm Eje50% (2)

- (Digest) Monroy V CADokument2 Seiten(Digest) Monroy V CACarlos Poblador100% (1)

- Binamira v. Garrucho, Jr. 188 SCRA 154Dokument2 SeitenBinamira v. Garrucho, Jr. 188 SCRA 154Manuel Villanueva100% (2)

- Laurel v. CSCDokument2 SeitenLaurel v. CSCCari Mangalindan Macaalay50% (2)

- Laurel v. Desierto Case DigestDokument2 SeitenLaurel v. Desierto Case DigestCari Mangalindan Macaalay100% (1)

- Soto Vs JarenoDokument1 SeiteSoto Vs JarenoTricia Sibal100% (1)

- CSC V JosonDokument2 SeitenCSC V Josonana ortizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Albert Vs GanganDokument2 SeitenAlbert Vs GanganJoe CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest GR No. 104732 Flores vs. DrilonDokument3 SeitenCase Digest GR No. 104732 Flores vs. DrilonRowell Ian Gana-an50% (2)

- 376 Garces Vs CADokument2 Seiten376 Garces Vs CACompos MentisNoch keine Bewertungen

- 141 Joson vs. NarioDokument3 Seiten141 Joson vs. NarioKEDNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSC Vs DACOYCOYDokument2 SeitenCSC Vs DACOYCOYaceamulong0% (1)

- 81 Rabor V CSCDokument4 Seiten81 Rabor V CSCKathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mitra vs. Subido Case DigestDokument2 SeitenMitra vs. Subido Case DigestPauline Mae AranetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maturan Vs Maglana, TUPAS Vs NHCDokument3 SeitenMaturan Vs Maglana, TUPAS Vs NHCaceamulongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sang B of Andres Vs CA Case DigestDokument2 SeitenSang B of Andres Vs CA Case DigestEbbe Dy100% (1)

- Quisumbing vs. GumbanDokument2 SeitenQuisumbing vs. GumbanXyra Krezel Gajete100% (1)

- G.R. No. 138238. September 2, 2003 Eduardo BALITAOSAN,, Petitioner, v. THEDokument4 SeitenG.R. No. 138238. September 2, 2003 Eduardo BALITAOSAN,, Petitioner, v. THEJanelle Leano MarianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laurel V Desierto (DIGEST)Dokument2 SeitenLaurel V Desierto (DIGEST)JohnAlexanderBelderol100% (1)

- Lacson V Romero Case DigestDokument1 SeiteLacson V Romero Case DigestReniel Dennis Ramos100% (2)

- Monetary Board Vs Philippine Veterans BankDokument1 SeiteMonetary Board Vs Philippine Veterans BankErish Jay Manalang100% (1)

- Republic v. Sereno DIGESTDokument5 SeitenRepublic v. Sereno DIGESTJor Lonzaga100% (6)

- Binamira Vs Garrucho, Jr.Dokument2 SeitenBinamira Vs Garrucho, Jr.John Lester TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monroy - v. - Court - of - AppealsDokument5 SeitenMonroy - v. - Court - of - AppealsMarl Dela ROsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case DigestDokument14 SeitenCase DigestTess LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Menzon V PetillaDokument4 SeitenMenzon V PetillaJed MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fernandez Vs Sto. TomasDokument2 SeitenFernandez Vs Sto. TomasLizzy Way100% (3)

- Yabut, Jr. v. Office of The OmbudsmanDokument2 SeitenYabut, Jr. v. Office of The OmbudsmanLance Lagman100% (1)

- 07) Career Executive V CSCDokument2 Seiten07) Career Executive V CSCAlfonso Miguel Lopez100% (1)

- G.R. No. L-12647 - Luna v. RodriguezDokument9 SeitenG.R. No. L-12647 - Luna v. RodriguezAj SobrevegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Digest) Achacoso V MacaraigDokument2 Seiten(Digest) Achacoso V MacaraigChristopher HermosisimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mendoza v. Laxina SRDokument2 SeitenMendoza v. Laxina SRGillian CalpitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pan v. PenaDokument2 SeitenPan v. PenaSophiaFrancescaEspinosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dimapilis-Baldoz v. CoaDokument2 SeitenDimapilis-Baldoz v. CoaBea Charisse MaravillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- US VS ABALOS DigestDokument2 SeitenUS VS ABALOS DigestEunice Cajayon100% (1)

- Planas Vs GilDokument2 SeitenPlanas Vs GilLouie RaotraotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abeja Vs TanadaDokument1 SeiteAbeja Vs TanadaLilaben SacoteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preclaro Vs SandiganbayanDokument1 SeitePreclaro Vs Sandiganbayanvaleryanns100% (2)

- Digest of Monroy v. CA (G.R. No. 23258)Dokument1 SeiteDigest of Monroy v. CA (G.R. No. 23258)Rafael PangilinanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canonizado CaseDokument2 SeitenCanonizado CaseJoshua LanzonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solis V CADokument3 SeitenSolis V CARomarie Abrazaldo100% (1)

- Meaning of Term Merely ExpiresDokument1 SeiteMeaning of Term Merely ExpiresraizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maglalang v. PagcorDokument3 SeitenMaglalang v. PagcorgorgeousveganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Service Commission vs. Pedro O. Dacoycoy G.R. No. 135805 April 29, 1999Dokument3 SeitenCivil Service Commission vs. Pedro O. Dacoycoy G.R. No. 135805 April 29, 1999Sandre Rose RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mendoza V Laxina Digest For Admin LawDokument1 SeiteMendoza V Laxina Digest For Admin LawchaynagirlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abeto V GarcesaDokument1 SeiteAbeto V GarcesaKenneth Peter MolaveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Service Commission Vs Pililla Water Distric CD February 8, 2014 Assignment For AttendanceDokument2 SeitenCivil Service Commission Vs Pililla Water Distric CD February 8, 2014 Assignment For AttendanceOscar E Valero100% (2)

- Law On Public Officers Case DigestDokument13 SeitenLaw On Public Officers Case DigestCMLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Debulgado V Civil Service CommissionDokument3 SeitenDebulgado V Civil Service CommissionIra AgtingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torres v. RiboDokument2 SeitenTorres v. RiboRaymond RoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Menzon V PetillaDokument2 SeitenMenzon V Petillaamazing_pinoy100% (5)

- Hon. Monetary Board v. PVB, G.R. No. 189571Dokument2 SeitenHon. Monetary Board v. PVB, G.R. No. 189571xxxaaxxx0% (1)

- 30 CD - Lecaroz Vs SandiganbayanDokument2 Seiten30 CD - Lecaroz Vs SandiganbayanRoby Renna EstoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecaroz Vs SandiganbayanDokument2 SeitenLecaroz Vs SandiganbayanCarie LawyerrNoch keine Bewertungen

- LECAROZ vs. SANDIGANBAYAN (Obiter Dicta Becoming Doctrines) FactsDokument2 SeitenLECAROZ vs. SANDIGANBAYAN (Obiter Dicta Becoming Doctrines) FactsPatricia BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aztala - Sales Agency Agreement v09Dokument3 SeitenAztala - Sales Agency Agreement v09ManoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kraft Box Supplier'sDokument4 SeitenKraft Box Supplier'sCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broker AgreementDokument4 SeitenBroker AgreementCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- DMCI租赁经纪人合作协议 BROKERS AGREEMENT PDFDokument3 SeitenDMCI租赁经纪人合作协议 BROKERS AGREEMENT PDFlei wangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broker AgreementDokument1 SeiteBroker AgreementCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broker AgreementDokument1 SeiteBroker AgreementCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jarco Marketing Corp v. CADokument11 SeitenJarco Marketing Corp v. CACari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rural Bank v. CADokument6 SeitenRural Bank v. CACari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Sec CertDokument3 SeitenSample Sec CertCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jimmy CoDokument5 SeitenJimmy CoCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lopez v. Pan American World (1966)Dokument4 SeitenLopez v. Pan American World (1966)Cari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. NoDokument6 SeitenG.R. NoCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Share Tweet: Like 0Dokument16 SeitenShare Tweet: Like 0Cari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ilocos Norte Electric CompanyDokument5 SeitenIlocos Norte Electric CompanyCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reissuance 2Dokument51 SeitenReissuance 2Cari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest - Lirio v. GenoviaDokument11 SeitenCase Digest - Lirio v. GenoviaCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- GSIS Loss of Title CaseDokument5 SeitenGSIS Loss of Title CaseCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quasi-Delict PrimerDokument5 SeitenQuasi-Delict PrimerCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cristostomo v. CA (25 August 2003) - Missing PlaneDokument6 SeitenCristostomo v. CA (25 August 2003) - Missing PlaneCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Co Unjieng v. Mabalacat SugarDokument4 SeitenCo Unjieng v. Mabalacat SugarCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reconstitution 1Dokument26 SeitenReconstitution 1Cari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Custom Search: Today Is Sunday, April 02, 2017Dokument11 SeitenCustom Search: Today Is Sunday, April 02, 2017Cari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tanongon Vs Samson - 140889 - May 9, 2002 - JDokument6 SeitenTanongon Vs Samson - 140889 - May 9, 2002 - JCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cruz Vs Gangan - 143403 - January 22, 2003 - J. Panganiban - en BancDokument5 SeitenCruz Vs Gangan - 143403 - January 22, 2003 - J. Panganiban - en BancCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- SEC - Form Foe E-Mail and Mobile NumberDokument4 SeitenSEC - Form Foe E-Mail and Mobile NumberCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caja Vs Nanquil - AM P-04-1885 - September 13, 2004 - JDokument15 SeitenCaja Vs Nanquil - AM P-04-1885 - September 13, 2004 - JCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emmanuel Concepcion, Et AlDokument16 SeitenEmmanuel Concepcion, Et AlCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bun v. CA (Tortious Intreference)Dokument5 SeitenBun v. CA (Tortious Intreference)Cari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Car Plan AgreementDokument4 SeitenCar Plan AgreementAdoniz Tabucal67% (12)

- Canlas v. CA (2000)Dokument7 SeitenCanlas v. CA (2000)Cari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greek Gods & Goddesses (Gods & Goddesses of Mythology) PDFDokument132 SeitenGreek Gods & Goddesses (Gods & Goddesses of Mythology) PDFgie cadusaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Swot MerckDokument3 SeitenSwot Mercktomassetya0% (1)

- The Message of Malachi 4Dokument7 SeitenThe Message of Malachi 4Ayeah GodloveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Bank: Corporate RestructuringDokument3 SeitenTest Bank: Corporate RestructuringYoukayzeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Service Application For ForgivenessDokument9 SeitenPublic Service Application For ForgivenessLateshia SpencerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michel Cuypers in The Tablet 19.6Dokument2 SeitenMichel Cuypers in The Tablet 19.6el_teologo100% (1)

- Easter in South KoreaDokument8 SeitenEaster in South KoreaДіана ГавришNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vietnam PR Agency Tender Invitation and Brief (Project Basis) - MSLDokument9 SeitenVietnam PR Agency Tender Invitation and Brief (Project Basis) - MSLtranyenminh12Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Absent Presence of Progressive Rock in The British Music Press 1968 1974 PDFDokument33 SeitenThe Absent Presence of Progressive Rock in The British Music Press 1968 1974 PDFwago_itNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digi Bill 13513651340.010360825015067633Dokument7 SeitenDigi Bill 13513651340.010360825015067633DAVENDRAN A/L KALIAPPAN MoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Matalam V Sandiganbayan - JasperDokument3 SeitenMatalam V Sandiganbayan - JasperJames LouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Dokument3 SeitenExecutive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Yanna PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.1 Cce To Proof of Cash Discussion ProblemsDokument3 Seiten1.1 Cce To Proof of Cash Discussion ProblemsGiyah UsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advt 09 2015Dokument8 SeitenAdvt 09 2015monotoshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Names of PartnerDokument7 SeitenNames of PartnerDana-Zaza BajicNoch keine Bewertungen

- TA Holdings Annual Report 2013Dokument100 SeitenTA Holdings Annual Report 2013Kristi DuranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historein11 (2011)Dokument242 SeitenHistorein11 (2011)Dimitris Plantzos100% (1)

- Tanishq Jewellery ProjectDokument42 SeitenTanishq Jewellery ProjectEmily BuchananNoch keine Bewertungen

- 205 Radicals of Chinese Characters PDFDokument7 Seiten205 Radicals of Chinese Characters PDFNathan2013100% (1)

- Marketing Plan11Dokument15 SeitenMarketing Plan11Jae Lani Macaya Resultan91% (11)

- Man of Spain - Francis Suarez. (Millar, M. F. X.) PDFDokument3 SeitenMan of Spain - Francis Suarez. (Millar, M. F. X.) PDFAdriel AkárioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Superstitions, Rituals and Postmodernism: A Discourse in Indian Context.Dokument7 SeitenSuperstitions, Rituals and Postmodernism: A Discourse in Indian Context.Dr.Indranil Sarkar M.A D.Litt.(Hon.)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Phoenix Surety vs. WoodworksDokument1 SeitePhilippine Phoenix Surety vs. WoodworksSimon James SemillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SUDAN A Country StudyDokument483 SeitenSUDAN A Country StudyAlicia Torija López Carmona Verea100% (1)

- Evening Street Review Number 1, Summer 2009Dokument100 SeitenEvening Street Review Number 1, Summer 2009Barbara BergmannNoch keine Bewertungen

- FINAL-Ordinance B.tech - 1Dokument12 SeitenFINAL-Ordinance B.tech - 1Utkarsh PathakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Can God Intervene$Dokument245 SeitenCan God Intervene$cemoara100% (1)

- Parent Leaflet Child Death Review v2Dokument24 SeitenParent Leaflet Child Death Review v2InJailOutSoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- IntroductionDokument37 SeitenIntroductionA ChowdhuryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strengths Finder Book SummaryDokument11 SeitenStrengths Finder Book Summaryangelcristina1189% (18)