Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Yr 3 Assignment

Hochgeladen von

Jake BurrOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Yr 3 Assignment

Hochgeladen von

Jake BurrCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

24563986

1 of 8

Section A

Case Study

Mr MP, a 66 year-old, retired council worker, attended clinic for his biannual active

surveillance check-up. Mr MP has been monitored for a raised prostate specific antigen

(PSA) level, caused by prostate cancer, for 16 years. He was initially found to have a raised

PSA through a blood test, after he presented with worsening urinary symptoms, including:

slow urinary flow, increased frequency and mild nocturia. The patient also commented that

he had no pain on urination but often experienced hesitancy and a feeling that he had not

100% emptied his bladder.

Over this period of 16 years, Mr MPs PSA level has increased from 2ng/ml to 10ng/ml with

his most recent PSA being 9.4ng/ml (normal PSA levels for men in their 60s is up to

4ng/ml

1

). This is only a small elevation in PSA level but biopsies have continued to show the

presence of cancer within the prostate; Mr MPs most recent biopsy showed a Gleason

score of 6, indicating the cancer cells are slow-growing

1

.

Mr MP had surgery 2 years ago for inguinal and umbilical hernias but has no other relevant

medical history. He is currently taking over-the-counter painkillers (ibuprofen and

paracetamol) for a sore shoulder and half a sleeping tablet each night, as he has been

having violent dreams over the last 2 months. On further discussion, Mr MP believes that

these dreams stem from the ongoing stress he has been experiencing since his diagnosis.

He further mentioned that he was worried about developing incontinence and sexual

dysfunction, especially if this resulted from surgery, and therefore stressed that he did not

want any invasive treatment for his cancer until absolutely necessary. Apart from these

dreams, the patient expressed that his diagnosis had not affected his daily life.

24563986

2 of 8

Epidemiology & Aetiology of Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer (PC) is the most common type of cancer in men and the second leading

cause of cancer mortality in males in Europe and the USA

2

. In 2008, an estimated 324,000

men were diagnosed with PC in Europe and around 899,000 men worldwide

3

. Approximately

1 in 9 men will be diagnosed with this form of cancer in their lifetime, with a 2-3% lifetime risk

of dying from the disease

2

.

It is estimated that the health and economic cost of PC is around 800m a year in the UK

4

;

three-quarters of this relating to the diagnosis, treatment and care of patients with PC, and

the remaining quarter relating to the economic losses from premature deaths and patients

taking time off when they are unable to work (as shown in Table 1)

4

.

Incidence figures have risen drastically in the previous two decades, however much of this

has been due to the increased use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening. The PSA

tests have led to the diagnosis of many more cancers, including some which may not have

presented clinically within the lifetimes of the patients concerned

5

. Autopsy data from males

dying from other causes have shown that the true prevalence of PC is actually far higher

than these incidence figures but in most men the disease remains latent during their life

2

.

The aetiology of PC is complex but many risk factors for its development have been

established.

Age is a well-known risk factor for the development of PC. It is very rare below the

age of 50, accounting for only 0.1% of cases. However, over 75% of cases are

diagnosed in men over 65

3

.

Healthcare and environmental factors have been found to correlate with an

increased incidence of PC. The USA, Australia and Scandinavia have the highest

rates and Japan and the Far East, the lowest. This data reflects the healthcare

practices (e.g increased use of PSA testing) and environmental factors (such as

pollution, infection and diet) of the population

2

.

24563986

3 of 8

Diets high in fat, high in red meat (especially barbecued) and low in vegetables have

been linked to the highest rates of PC. Diet is often related to the country of origin (as

indicated above) e.g. the Japanese population consume less fat than the American

population, and they have a lower incidence of PC

2

.

Family history of PC also presents an increased risk of developing the disease.

Having a first-degree relative diagnosed with PC doubles the risk of PC

6

.

Testosterone is the main hormone controlling the growth and function of the

prostate. Cancer is rarely found in castrated men or those suffering from familial

congenital testosterone metabolism defects, such as 5-alpha-reductase deficiency

2

.

As well as this, higher testosterone levels have been found in the African-American

population, possibly indicating why the increased incidence of PC in this population

when compared to Caucasian men

6

.

Psychosocial Aspects of PC

It is not only the physical symptoms of PC that need to be addressed, but also the wide-

array of psychological issues that the patient may experience. Psychological and social

issues develop in between 30-50% of PC patients. This is irrespective of the severity of their

disease and the treatment they receive

7

. Depression, anxiety and stress, often seen as a

response to the pain, sexual dysfunction and urinary problems that are seen in PC, can

develop at any point in the timeline of the disease.

Anxiety

The types of anxiety seen with patients with PC vary, but it is thought that at any given time

20-60%

8

of PC patients suffer from the issue, with 30-40% of patients complaining that their

24563986

4 of 8

anxiety is affecting their daily lives

9

. It can affect the patient at any stage: during testing for

PC (including PSA testing), at the time of diagnosis, as well as before and during treatment

8

.

It seems that PSA levels are the basis of a significant amount of anxiety for a PC patient. An

abnormal PSA level can be caused by a number of mechanisms and therefore the

uncertainty of a diagnosis can cause stress. Thereby, it was found that anxiety reduced even

when a diagnosis of PC was given, as the uncertainty was removed

10

.

Depression

Depression is strongly correlated to pain and fatigue, symptoms often seen in the late stages

of PC. As well as this, erectile dysfunction & urinary incontinence, complications that many

men diagnosed with PC fear, have a clear link with depressive symptoms

9

.

Interestingly, in studies comparing psychological distress in men with PC and their partners,

it was suggested that the partners risk of depressive symptoms is as high or higher that the

patients

11

, clearly showing how PC can affect, not just the patient, but their family, friends

and surrounding others.

As such, when treating PC, irrespective of stage, the physician needs to consider the family

as well as social and psychological perspectives before making any decisions about a

treatment plan. A multi-disciplinary approach, including urologists, psychiatrists and

psychologists, is required, in order to treat the physical and psychological aspects that are

causing the patients depression and anxiety and address the concerns of carers and loved

ones.

24563986

5 of 8

Section B

The majority (>95%) of prostate tumours are adenocarcinomas arising from prostatic

epithelial cells

12

. However, it is important to recognise the rarer histologies; carcinoid

tumours, large prostatic duct carcinomas, small-cell undifferentiated cancer etc, as certain

therapies will be less effective against these

12

. The peripheral zone of the prostate, located

at the back of the prostate gland, (shown in Figure 1

12

) is the most common area for an

adenocarcinoma to develop, with about 70-75% of PCs occuring here

13

.

PC and PIN

Cancer is generally thought of as a multi-step process; a continuous series of genetic and

cellular events render the tumour increasingly malignant. This can be seen in PC, through

the development of pre-malignant lesions, which may present many years before an

invasive carcinoma develops

14

, and that are now recognized to lead to the development of

PC

15

. These pre-malignant lesions are known as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia or PIN.

PIN is defined as the presence of cytologically atypical or dysplastic epithelial cells within

architecturally benign-appearing glands and acini

12

(an example of PIN is given in Figure

2

12

). It represents neoplasia that has not yet invaded through the basement membrane.

Molecular Basis

The molecular determinants of PC are an essential area of research and have been under

intense investigation for many years. The main areas of research I will discuss are: mutation

of genes involved with prostate gland development (NKX3.1) as well as activation (Myc) and

loss of tumour-suppression (PTEN& RB).

24563986

6 of 8

NKX3.1

The NKX3.1 gene is located on chromosome 8p21. It has been found that this region

displays heterozygous loss in 50% of primary PC patients and 80% loss in those with

metastatic disease

15

. As well as this, in mouse models, loss of the NXK3.1 gene (a gene that

acts as a transcription factor involved in organogenesis, but also has tumour-suppressing

effects) alongside Myc over expression (discussed below), results in the development of PIN

and eventually micro-invasive cancer

16

.

These two pieces of evidence are strongly suggestive that the NKX3.1 gene plays an

important part in the development of PC.

Myc

The proto-oncogene Myc is a transcription factor that regulates gene expression in many

biological processes. Myc is located on chromosome 8q24,a locus that is often amplified in

PC patients (around 30%)

15

. Mouse models have shown that, in mice with engineered

Super-Lo, Lo or Hi levels of Myc expression, all groups spontaneously developed PIN

and the Lo and Hi groups developed invasive disease. This suggested that Myc over-

expression alone could cause tumour formation

17

.

PTEN (P13K pathway)

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (P13K) through a complex cascade of reactions (shown in

Figure 3

18

) activates AKT, a protein kinase involved with cell proliferation, transcription and

cell migration. This AKT activation is regulated by PTEN.

PTEN is a tumour suppressor, acting in the opposite way to P13K, dephosphorylating PIP3

to PIP2 and reducing AKT activation. It has been found that a loss of a single PTEN allele,

leaving AKT unregulated, can start the development of early stage PC (70% of primary PCs

have a haploid loss of PTEN) and loss of the second allele, alongside other genetic

mutations, leads to the development of invasive disease

19

.

24563986

7 of 8

RB

p130 retinoblastoma (RB) protein is a tumour suppressor; its loss is associated with many

epithelial cancers. The proteins function is to regulate cell-cycle progression and in the

context of cancer, its absence causes the cell cycle to run abnormally, leading to

uncontrolled cell proliferation

20

. RB loss was found in over 70% of castrate-resistant PC

specimens and it has been found that an RB loss signature is associated with poor cancer

prognosis

15

.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentations of PC are a result of the invasive growth of the tumour, its spread

to regional lymph nodes and its transport, via the blood, to other sites.

Early stage PC is mostly diagnosed through a routine blood test, as the patient is usually

asymptomatic at this time. At later stages, urinary symptoms may begin to occur. Local

tumour growth can disrupt the urethra or the bladder neck, and may also push into the

trigone area of the bladder. This can lead to obstructive or irritative symptoms

21

, including

increased urinary frequency including nocturia, retaining urine, difficulty passing urine

(straining or stop/start), dysuria and haematuria. It is important that the relevant

investigations are done to ensure these symptoms are not caused by benign prostatic

hyperplasia (BPH).

PC most often spreads to bone

21

and this often presents as localised bone pain, commonly

in the back due to vertebral metastases. Pathological fracture and peripheral

lymphadenopathy are other common presentations

14

.

Conclusion

PC does not have a single cause. Its initiation is most likely caused by a complex array of

genetic mutations, many of which are still being researched. In the near future, with the

increased use of whole-genome sequencing it is hoped that we will be possess the ability to

24563986

8 of 8

determine precisely what mutations or losses are seen in a given patients prostate tumour,

allowing us to treat the precise abnormality. Until then, the onus lies with the physician, and

the development of individualised treatment plans, to deal with and treat, not only the

physical symptoms of the disease but the important psychological issues that may arise.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Audience AnalysisDokument7 SeitenAudience AnalysisSHAHKOT GRIDNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02 Cost of Capital QBDokument26 Seiten02 Cost of Capital QBAbhi JayakumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Case Study On Implementing ITIL in Bus PDFDokument7 SeitenA Case Study On Implementing ITIL in Bus PDFsayeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Existentialism Is A HumanismDokument4 SeitenExistentialism Is A HumanismAlex MendezNoch keine Bewertungen

- As 3778.6.3-1992 Measurement of Water Flow in Open Channels Measuring Devices Instruments and Equipment - CalDokument7 SeitenAs 3778.6.3-1992 Measurement of Water Flow in Open Channels Measuring Devices Instruments and Equipment - CalSAI Global - APACNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Create A MetacogDokument6 SeitenHow To Create A Metacogdocumentos lleserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revolute-Input Delta Robot DescriptionDokument43 SeitenRevolute-Input Delta Robot DescriptionIbrahim EssamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shortcut To Spanish Component #1 Cognates - How To Learn 1000s of Spanish Words InstantlyDokument2 SeitenShortcut To Spanish Component #1 Cognates - How To Learn 1000s of Spanish Words InstantlyCaptain AmericaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ardipithecus Ramidus Is A Hominin Species Dating To Between 4.5 and 4.2 Million Years AgoDokument5 SeitenArdipithecus Ramidus Is A Hominin Species Dating To Between 4.5 and 4.2 Million Years AgoBianca IrimieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Duah'sDokument3 SeitenDuah'sZareefNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamics of Bases F 00 BarkDokument476 SeitenDynamics of Bases F 00 BarkMoaz MoazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diversity and InclusionDokument23 SeitenDiversity and InclusionJasper Andrew Adjarani80% (5)

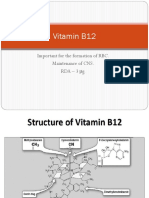

- Vitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceDokument19 SeitenVitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceHari PrasathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physics 401 Assignment # Retarded Potentials Solutions:: Wed. 15 Mar. 2006 - Finish by Wed. 22 MarDokument3 SeitenPhysics 401 Assignment # Retarded Potentials Solutions:: Wed. 15 Mar. 2006 - Finish by Wed. 22 MarSruti SatyasmitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 Oh OverviewDokument50 Seiten01 Oh OverviewJaidil YakopNoch keine Bewertungen

- Court Testimony-WpsDokument3 SeitenCourt Testimony-WpsCrisanto HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Branding dan Positioning Mempengaruhi Perilaku Pemilih di Kabupaten Bone BolangoDokument17 SeitenPersonal Branding dan Positioning Mempengaruhi Perilaku Pemilih di Kabupaten Bone BolangoMuhammad Irfan BasriNoch keine Bewertungen

- High Intermediate Analogies 9Dokument2 SeitenHigh Intermediate Analogies 9Usman KhalidNoch keine Bewertungen

- M5-2 CE 2131 Closed Traverse - Interior Angles V2021Dokument19 SeitenM5-2 CE 2131 Closed Traverse - Interior Angles V2021Kiziahlyn Fiona BibayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Listening LP1Dokument6 SeitenListening LP1Zee KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cost-Benefit Analysis of The ATM Automatic DepositDokument14 SeitenCost-Benefit Analysis of The ATM Automatic DepositBhanupriyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Registration details of employees and business ownersDokument61 SeitenRegistration details of employees and business ownersEMAMNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Students Playwriting For Language DevelopmentDokument3 SeitenStudents Playwriting For Language DevelopmentSchmetterling TraurigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pyrolysis: Mathematical Modeling of Hydrocarbon Pyrolysis ReactionsDokument8 SeitenPyrolysis: Mathematical Modeling of Hydrocarbon Pyrolysis ReactionsBahar MeschiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 6. TNCTDokument32 SeitenLesson 6. TNCTEsther EdaniolNoch keine Bewertungen

- FortiMail Log Message Reference v300Dokument92 SeitenFortiMail Log Message Reference v300Ronald Vega VilchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnovaDokument26 SeitenAnovaMuhammad NasimNoch keine Bewertungen

- ML Performance Improvement CheatsheetDokument11 SeitenML Performance Improvement Cheatsheetrahulsukhija100% (1)

- Unit 3 Activity 1-1597187907Dokument3 SeitenUnit 3 Activity 1-1597187907Bryan SaltosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Way To Sell: Powered byDokument25 SeitenThe Way To Sell: Powered bysagarsononiNoch keine Bewertungen