Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Creative Value Engineering

Hochgeladen von

Akash PandeyOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Creative Value Engineering

Hochgeladen von

Akash PandeyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Vol: 1 No: 3 September 1968

VALUE

ENGINEERING

In this issue

Editorial - R. Perkins- Value Satisfaction and Profit

Contractual Value Engineering Provisions in the United States

by K. M. Jackson

The Constraints to Creative Value Engineering

by Ll. Colonel B. Decker

Stimulation of the Individual

by F. S. Slier win

The New Management Tool - Value Administration

by A. G. Chappell

The Contribution of Ergonomics to Value Engineering

by K. F. H. Murrell

Ergonomics Checklist

The Challenge of Value Engineering - The Theory behind the Savings

by F. R. Bowyer

The Numerical Evaluation of Functional Relationships

by A. E. Mudge

Organising the V.E.-Effort in a Company

by J. Burnside

The Application of V. E. Effort for Maximum Effectiveness

by G. P. Jacobs

The Value Engineer's Bookshelf

Selected Abstracts of Recent Literature on Value Analysis/Engineering

Page

133

135

139

143

147

149

153

165

169

177

179

183

191

Pergamon Press

The Al Mof Value Engineering

is to encourage the wider use of value analysis/engineering techniques

throughout industry.

Value Engineering

provides a link between those-who are practising and studying the subject

all over the world.

It is the POLICY of the journal

to contain information which promotes the wider and more efficient application

of value analysis/engineering methods.

Its ABSTRACTING SERVI CE

will draw attention in a conveniently summarised form to the main publications

on the subject throughout the world.

* * *

Key-word Index

A number of readers have asked for the system for information retrieval to be

explained more fully.

The key-word system - unlike titles which sometimes cannot cover all the

aspects of an article, book review or abstract - signifies those facets of the

subject which are covered. For example, the article 'The Constraints to Creative

Value Engineering' covers Value Standards yet this was not specifically indicated

by the title.

By referencing the article to two cards measuring 5" x 3", arranged alphabeti-

cally the value engineer can build up a system of reference to articles on

Creativity and Value Standards.

The list of key-words will be built up issue by issue until a useful list of key-

words covering value engineering subjects can be published in a future issue

of the journal.

Reprint Service

Reprints of the articles and checklists appearing in Value Engineering may be

ordered in multiples of fifty copies and detachable ordering forms are provided

opposite.

* * *

Value Engineering is published bi-monthly by Pergamon Press Ltd.

The Editor is Bruce D. Whitwell, 20 Pelham Court, Hemel Hempstead, Herts.,

England. Telephone: Hemel Hempstead 3554.

Advertisement Offices

Pergamon Press Ltd., 348 Gray's Inn Road, London WC1, England.

Telephone: 01 -837 6484

Production Offices

Pergamon Press Ltd., T. & T. Journals, Headington Hill Hall, Oxford, England.

Telephone: Oxford 64881.

Subscription Enquiries

Pergamon Press Ltd., Headington Hill Hall, Oxford, England.

Pergamon Press Inc., 44-01 21st Street, Long Island City, New York. NY.

11101, U.S.A.

Annual Subscription

3.10.0 (U.K. only) post free.

U.S.A. and Canada $9.00.

Overseas 3.10.0 post free.

The publisher reserves the right to dispose of advertisement colour blocks after

twelve months, monotone blocks after six months with or without prior

notification.

Reprints from Value Engineering

V alue E ngi neer i ng i s provi di ng a ser v i c e by whi c h r epr i nt s of any ar t i cle or c hec kli st c an be suppli ed at shor t not i ce.

For det ai ls of pr i c es exc lusi v e of post age see below.

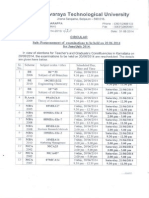

No. of

Repr i nt s 1-2 pp 3- 4 pp 5-6 pp 7-8 pp 9-10 pp

50 4. 5. 0. 8. 5. 0. 12. 0. 0. 16. 0. 0. 19. 15. 0.

100 5. 0. 0. 9. 10. 0. 13. 15. 0. 18. 0. 0. 22. 5. 0.

200 6. 15. 0. 12. 0. 0. 16. 15. 0. 21. 15. 0. 26. 15. 0.

300 8. 10. 0. 14. 5. 0. 20. 0. 0. 25. 15. 0. 31. 10. 0.

400 10. 0. 0. 16. 10. 0. 23. 0. 0. 29. 10. 0. 36. 0. 0.

500 11. 15. 0. 19. 0. 0. 26. 5. 0. 33. 10. 0. 40. 15. 0.

750 16. 0. 0. 25. 0. 0. 33. 0. 0. 43. 5. 0. 52. 5. 0.

1,000 20. 0. 0. 31. 0. 0. 40. 0. 0. 53. 0. 0. 64. 0. 0.

1,250 24. 0. 0. 37. 0. 0. 47. 0. 0. 62. 0. 0. 75. 10. 0.

1,500 28. 5. 0. 43. 0. 0. ' u 53. 15. 0. 72. 0. 0. 87. 5. 0.

2,000 36. 15. 0. 55. 0. 0. 68. 0. 0. 82. 0. 0. 110. 15. 0.

2,500

t

45. 5. 0. 67. 0. 0. 82. 5. 0. 101. 10. 0. 134. 5. 0.

3,000 53. 15. 0. 79. 0. 0. 96. 10. 0. 121. 0. 0. 157. 15. 0.

3,500 62. 5. 0. 91. 0. 0. 110. 15. 0. 140. 10. 0. 181. 5. 0.

4,000 70. 15. 0. 103. 0. 0. 125. 0. 0. 160. 0. 0. 204. 15. 0.

5,000 87. 15. 0. 127. 0. 0. 153. 10. 0. 199. 0. 0. 251. 15. 0.

Prices for orders in excess of those quoted will be given on request.

Standard covers, showing only the Journal title and Publisher's name, are provided free. Any special cover requirements

will be subject to quotation. Please use the cards provided below for your reprints order.

CD

Q)

o

c

cn

)'

3

CD

Q-

CD

01

CO

CD

0)'

CD ^

CD

T3

15 *

O)

CO

CD

Q.

CD

O

O

3

<

o

o"

CD

CD

CL

30

CD

T3

CD O 5"

rr, r f .

r

*

3

C

3

cr

CD

c

3

cr

CD

=: ! ' 2,

T3

Q>

CQ

CD

CD

3

CD

CL

CD

n

c

CD

T3

3

CO

0)

3

CL

O)

O

O

<

CD

3"

CD

QJ

cV

CD

o

o

D

CD'

cn

3

c

CO

r+

CT

CD

CL

CD

CD

CL

3

c

CD

CO

Ol

O

<

SL

c

CD

m

3

CO

5'

CD

CD

5"

to

30

CD

TJ

5'

r+

CO

(A

CD

O

CD

(J)

'CQ

-

< CD

CL

CD

0)

CO

CD

CO

CD

3

CL

o

c

2 %

CD

CD

CO

CD

o

9L

TJ

c

o

3"

03

CO

CD

Q.

CD

o_

O

3

<

o

o'

CD

CD

CL

DO

CD

T3

2 =

3

C

CT

CD

3

cr

CD

^ 5- a

T3

Q)

CQ

CD

CO

CD

3

CD

Q.

CD

c

CD

"D

3

CO

so

3

CL

Q>

O

o

<

CD

0)

CD

o

o

"U

co

3

c

CO

^+

cr

CD

CL

CD

I

CD

CL

3

c

CD

CO

O

<

2L

c

CD

m

3

CO

5'

CD

CD

5'

CO

3]

CD

TJ

5'

r+

CO

CO

CD

O

CD

Three Guineas a year

isn't much to add to your firm's training bill, but

Industrial Training International

every month is a great deal to add to your firm's stock of expertise on the com-

plicated subject of training.

Particularly in these days of rapid change and increasing use of new training

methods and aids, you should keep yourself well informed.

Write for a free specimen copy to 'Industrial Training International',

Pergamon Press, Headington Hill Hall, Oxford, England.

I n t h i s i s s u e :

C ont r a c t ua l V a lue E ngi neer i ng

P r ov i si ons in t he Uni t ed S t a t e s

Kenneth M. Jackson

Manager of Contracts,

Dynalectron Corporation

T h e C ons t r a i nt s t o C r eat i v e V a lu e

E ngi neer i ng

Bert Decker

Director of Project 3000 at the State

University of New York at Buffalo

S t i mulat i on of t he I ndi vi dual

Frederick S. Sherwin

Value Engineering Coordinator,

The Plessey Company Ltd.

T h e N e w Ma na g e me nt Tool -

V a lue Admi ni st r at i on

Anthony G. Chappell

Deputy Managing Director,

Mead Carney & Company Ltd.

There is a great deal of interest in the way in whi ch the U.S. Department of

Defense operates V.E. clauses in contracts wi th its suppliers and this article

describes such clauses in the Armed Services Procurement Regulation. After

half a dozen years a vast potential still exists for savings for of the $45 billion to be

spent in defense procurement in 1968 projected savings only amount to 0-3

per cent.

As well as describing the constraints - habitual, semantic, and educational - the

author puts forward ideas for overcoming them. Managers, he says, cannot

effectively manage that whi ch they do not clearly understand, and the need is

for a definition of value in verifiable measurable terms. The integration of value

engineering into the organisation should be the aim. Teach those inside so it is

they who cut the costs.

The article outlines how management can best stimulate the individual and

overcome the barriers Jo motivation. The dangers whi ch come from the 'extra

effort' philosophy are highlighted. The amount of stimulation upon the individual

should be proportional to the influence whi ch the individual exerts on costs.

Management leadership is prime to all techniques for cost improvement.

The author discusses the weaknesses in the methods of reducing overhead costs

and advocates 'Value Administration' as an effective alternative. Value

Administration' whi ch is based on the functional analysis of activities has as its

objective the comparison of the function wi th its cost. The vital need for

Management support is stressed.

T h e C ont r i but i on of E r g o n o mi c s

t o V a lue E ngi neer i ng

K. F. H. Murrell

Reader in Occupational Psychology,

University of Wales Institute of Science

and Technology

Value engineering should not stop short of its completion point - the perfor-

mance of the product. This can be ensured by applying ergonomic principles to

design, manufacture and use. Equipment whi ch is produced for sale should be

assessed for its overall efficiency when operated by a human operator.

T h e C ha lle ng e of V . E . - T h e The or y

behi nd t he S a v i ng s

Frank R. Bowyer

Consultant, Value Engineering Ltd.

T h e Numer i c al E v aluat i on of

F unc t i onal Relat i onshi ps

Arthur E. Mudge

Director of Value Engineering Services,

JOY Manufacturing Company

O r gani si ng t he V . E . - E f f o r t in a

C o mp a n y

J. Burnside

Assistant to the Deputy Chairman

(Engineering), Lindustries Ltd.

T h e Appli c at i on of V . E . E f f or t f or

Ma x i mu m E f f e c t i v e ne s s

G. P. Jacobs

Manager of Value Engineering, British

Aircraft Corporation (Operating) Ltd.

(Weybridge Division)

In this second of five articles the author asks ' Why bother about a theory of

value engineering?' He puts forward forty postulates for consideration as a

basis of a theory of value engineering.

Continuing the consideration of functional worth from the Jul y issue the author

points out precise functional balance is that whi ch makes a product both work

wel l and sell effectively at the lowest total cost. The article describes methods

whi ch the value engineer can use to evaluate functional relationships of products

whi ch he is called upon to analyse.

In the first of three articles a Profit Improvement Programme is discussed and the

areas in whi ch it can be applied are shown. The requirements of small as wel l

as medium and large companies are given attention.

Attention is drawn to the need for employees to appreciate that their overall

objective is to improve their company's ability to make profit. The value engineer

has to judge the area in whi ch his work is most likely to produce results, and he

can often make his greatest contribution in 'upstream' work during the project

definition stage. The need for a continuing programme of value research is

stressed.

C H E C K L I S T S Ergonomics Checklist

Pitfalls and Weaknesses to Avoid in Establishing Value Analysis or Engineering

in a Company

B O O K R E V I E W S Ergonomics - Man and His Environment (Murrell, K. F. H.)

Materials for Engineering Production (Houghton, P. S.)

The Enterprise and Factors Affecting its Operation (Roberts, C.

The New Materials (Fishlock, D.)

Fitting the Job to the Worker (O.E.C.D.)

R.)

Value Engineering, September 1968 129

B O O K RE V I E WS c ont i nue d Fundamentals of Operations Research (Ackoff, R. L. and Sasieni, M. W.)

Design Engineering Guide - Value Engineering (Roberts, J. C. H.)

Teach Yourself Statistics (Goodman, R.)

Quality Control Handbook (Juran, J. M.) (ed.)

A Search for V.E. Improvement (2 vols.) (SAVE)

SAVE - Volume 3 (Proceedings 1968 National Conference)

SAVE - Volume 2 (Proceedings 1967 National Conference)

Application of Value Analysis/Engineering Skills (Bl yth, J. and Woodward, R.)

How to Cut Office Costs (Longman, H. H.)

Modern Management Methods (Dale, E. and Michelon, L. C.)

Design Engineering Guide - Electric Controls (Weaver, G. G.) (ed.)

Design Engineering Guide - Adhesives (Philpott, B.A.) (ed.)

Operational Research (Makower, M. S. and Williamson, E.)

The Art of Decision Making (Cooper, J. D.)

Design Engineering Handbook - Metals (Product Journals Ltd.)

Propulsion Without Wheels (Laithwaite, E. R.)

Machinery Buyers' Guide 1968 (Machinery Publishing Co. Ltd.)

Creative Synthesis in Design (Alger, J. R. M. and Hays, C. V.)

Purchasing Handbook (Aljian, G. W.) (ed.)

Handbook of Fastening and Joining Metal Parts (Laughner, V. and Hargan, A.)

Materials Handbook (Brady, G. S.)

Measurement and Control of Office Costs (Birn, S. A., et al)

Design Engineering Guide - Fluidics (Product Journals Ltd.)

Value Analysis - The Rewarding Infection (Gibson, J. F.)

Design Engineering Guide - Metrigrams (Product Journals Ltd.)

Main Economic Indicators (O.E.C.D.)

Mechanical Details for Product Design (Greenwood, D. C.) (ed.)

Engineering Data for Product Design (Greenwood, D. C.)

Engineering Materials Handbook (Mantell, C. L.) (ed.)

Fundamentals of Numerical Control (Lockwood, F. B.)

Municipal Work Study (Mi l l ward, J. G.)

Product Engineering Design (Greenwood, D. C.)

Quality Control for the Manager (Cowan, A. F.)

Essays on Creativity in the Sciences (Coler, M. A.) (ed.)

AB S T R AC T S [36] to [45]

In future issues:

Value Control at the North American Rockwell Corporation Commercial Products Group

by E. J. Williams, Vice-President of Manufacturing and Facilities

Patents for Inventions

by Frank Newby, Information and Patents Officer, Hardman Et Holden Ltd.

Organising the V.E.-Effort in a Company; Parts 2 and 3

by J. Burnside, Assistant to the Deputy Chairman, Lindustries Ltd.

The Challenge of V.E. - Making the Theory Work; Training for V.E.; Value Engineering Development

by F. R. Bowyer, Consultant, Value Engineering Ltd.

Insuring an Effective V.E. Workshop Seminar

by J. J. Kaufman, Manager of Industrial and Value Engineering, Honeywell Inc. Aerospace Division

What is a Value Engineer?

by Patricia B. Livingston, Management Systems Analyst, North American Rockwell Corporation, Space Division

Should V.E. be Value Engineering Itself?

by J. Harry Martin, Manager of Value Engineering, General Electric Company, Ordnance Department

How Instant Money Works

Describing the Kaiser Aluminium and Chemical Corporation's Accounts Payable System

Value Engineering - Dynamic Tool for Profit Planning

by George H. Fridholm, George Fridholm Associates

The Value Manager

by Bert J. Decker, Director of Project 3000, State University of New York at Buffalo

Questionnaire - The Value Engineer in Private Industry

130

Value Engineering, September 1968

EDITOR: Bruce D. Whi twel l , Industrial Economist

R E G I O N AL E D I T O R S

CANADA: Mr C. Bebbington,

Value Program Coordinator,

United Aircraft of Canada Ltd.,

P.O. Box 10, Longueuil, Quebec.

NORTH EASTERN UNITED STATES:

SOUTHERN UNITED STATES:

Lt.-Col. Bert J. Decker, USAFR (Ret.),

Director, Project 3000,

Millard Fillmore College,

State University of New York at Buffalo,

Hayes A, Buffalo, N.Y. 14214.

Mr F. Delves,

Lockheed-Georgia Company,

Marietta, Georgia.

WESTERN UNITED STATES: Mrs. Patricia B. Livingston,

Management Systems Analyst,

North American Rockwell Inc.,

Space Division, Downey, California.

UNITED KI NGDOM: Mr R. Perkins,

Technical and Works Director,

Barfords of Belton Ltd.,

Belton, Grantham, Lines.

EUROPE: Mr. P. F. Thew,

Manager - Industrial Engineering,

I.T.T. Europe Inc.,

11 Boulevard de I'Empereur,

Brussels 1, Belgium.

T h e Regi onal E di t or f or t he Uni t ed Ki ng dom

Mr R. Perkins, C.Eng., F.I.Mech.E., M.B.I.M., F.I.D.

Mr Perkins, who has contributed the editorial to this issue, began his career as an engineering apprentice at the London

Midland and Scottish Railway Locomotive Works at Derby. After worki ng as a Planning Engineer he joined the British

Celanese Engineering staff.

In 1951 he became an adviser t o the United States Air Force, coordinating American and British mechanical and electrical

engineering practice. Mr Perkins then resided in the West Indies for seven years, where he held an appointment as Director

of Electrical and Mechanical Services in the Ministry of Communications and Works, Jamaica.

For the last seven years, Mr Perkins has been wi t h the Aveling Barford Group, where he is currently Technical and Works

Director for the subsidiary, Barfords of Belton Ltd.

Mr Perkins is married wi t h four children and takes a keen interest in golf. He is chairman of the South Lincolnshire

Productivity Association whi ch organises seminars and open meetings on behalf of the British Productivity Council.

Value Engineering, September 1968 131

Long Range PlanningThe Journal of the Society for

Long Range Planninga new quarterly publication from

Pergamon.

Editor: Bernard Taylor

The Management Centre, University of Bradford.

This is an international journal which aims to focus the

attitudes of Senior Managers, Administrators and

Academics on the concepts and techniques involved in

the development of strategy and the generation of Long

Range Plans.

Contents of Volume 1 Number 1

Long Range Planningthe Concept and the Need

B y H. F. R. P er r i n

Analytical Techniques in Planning

Long Range Planning of Managers

By D. J . S ma lt e r

By H. P. F or d

Technological Forecasting in Corporate Planning

By E . J a n t s c h

The Fading of an Ideology

By C . C . B r o wn

New Methods of Economic Management must be

developed B y J . Br ay

The Strategic Dimension of Computer Systems

Planning B y C . H. Kr i ebel

Mergers and British Industry

Price: 10.0.0 per annum.

By N. A. H. S t a c e y

Inspection copies and orders to the

Training & Technical Publications Division,

Pergamon Press Limited,

Headington Hill Hall, Oxford.

132

Value Engineering, September 1968

Reprint No. 1:3:1

Editorial:

Mr R. Perkins, the British Regional Editor o f V a lue E ngi neer i ng is Technical Director of Barfords of

Be/ton Ltd. He has kindly accepted the invitation to write the editorial. Readers, Mr Perkins. . .

Value Satisfaction and Profit

I n business, coordinat ion of effort leads t o success, bu t t o succeed

there must be a profit . Whether it be a produ ct- or a service-

oriented company, wit hou t mot ivat ion, involvement, uniqueness

and value, the goal of satisfaction wil l not be reached.

A short statement of what business is al l about is provided by the

Harvard School of Business: 'Businesses exist t o creat value

satisfaction at a profit'. You may wel l ask, how many people

keep such a simple axiom as this constantly before them? I

submit t o you that the whole concept of value engineering is

bou nd u p in providing the value satisfaction wit hou t which there

can never be any profit.

From my personal experience, value engineering and analysis

has produced increased profit s, and facts and figures have been

produced time and again t o su pport this statement. So the answer

t o ' Why Valu e Engineering?' is equally simpl e-it provides a

proven discipline which wil l produce profit .

I t is interesting t o note that one of the factors taken int o account

when carrying ou t a creative corporate planning exercise is

'the ret u rn on sales'. This ret u rn on sales is a measure of a

company's uniqueness and it shows the value given in its products

or services.

The Editors of Value Engineering are vit al l y concerned that the

techniques of Valu e Analysis and Engineering shou ld be recog-

nised as a sure means of improving the profit abil it y of a company

wit hou t losing any of the uniqueness and value satisfaction of

its produ cts.

A l l companies of whatever type are part of a chain of demand

starting wit h the consumer and extending back t hrou gh al l

forms of indu stry t o agricu ltu re and mining. Each business takes

something from another business, modifies it in some way and

passes it on t o others. I n modifying the company adds value and

obtains a ret u rn on sales which is proport ional t o that value and

its uniqueness. Whil st value in this sense is affected by the

complete corporate plan, the part played by a sound Valu e

Engineering fu nct ion wit hin a company can make a tremendous

cont ribu t ion towards ensuring an adequate ret u rn on the capital

invested by the company's shareholders.

I f a new way is fou nd t o produce a new or an existing produ ct at a

lower cost while retaining the product value then a company wil l -

for a t ime at least - lead its competitors.

The obvious enthusiasm and detail set ou t in the articles on value

engineering are a sure indicat ion of the success it enjoys. I t is

only fair t o sound a note of warning. A l l real success in this fiel d

is based on a methodical approach and unless this is taught the

practitioners cou l d bring value engineering int o disrepute.

Valu e Engineering crossed the At l ant ic in 1957 and many Brit ish

companies have set u p V. E. departments; others have fou nd con-

sultants t o be most u sefu l in t raining their staffs and fol l owing u p

the progress they are making. Personal experience of bot h ways

has given me a preferencefor the latter method. I t ensures that the

company line management can get on wit h their fu nct ions whil e

the V. E. department staff are t rained in V. E. ' techniques and

methodology by someone f r om outside. The outside con-

sultant brings a fresh mind t o bear on the problems encountered

and - i f he be retained t o make periodical visits - can supply an

independent report on progress t o the Chief Executive.

A l l those who are engaged in value engineering wil l be aware

that t o be successful you need involvement at the t op. The best

way t o get involvement is t o make involvement easy. There are

very few senior executives who are not prepared t o listen t o a

reasoned, honest report which wil l save him money. There are,

however, many executives whose day t o day line management

activities preclude t hem giving of t heir best t o su pporting the

value engineering team. I t wou l d appear in practice very difficu l t

for a senior executive t o keep in the forefront of his thoughts

that ' Valu e Engineering equals guaranteed increased profit s' .

The practice of V. E. is one of to-day's most satisfying activities

and greatest cont ribu t ors t o increased company profit s.

Value Engineering, September 1968

133

Castings

or

Fabricatio:

Why not

combine

them?

J i a r p e r

c ast i ngs

For some time John Harper & Co. Ltd. have been investigating the techniques

and problems of welding S. G. Iron castings for inclusion in larger fabrications.

The practical benefits of this work are the subject of a John Harper publication

' Welding Harper S. G. Iron'.

The brochure covers: -

Applications; demonstrating the advantages of combining the casting and

fabrication processes.

Techniques; outlining the theoretical basis of welding Harper S. G. Iron.

Processes; the variety of welding processes applicable with practical inform-

ation on their selection and use.

Fill in the coupon below for your free copy.

r

To John Harper & Co. Ltd., Al bi on Works, Willenhall, Staffs.

Please send me your leaflet

Weldi ng Har per S . G . I r on.

NAME

POSI TI ON

FI RM

AD D R E S S

1 _

H739

134 Value Engineering, September 196H

Reprint No. 1:3:2

Contractual VE - DoD - British Industry - Armed Services Procurement Regulations

Contractual Value Engineering Provisions

in the United States

by Kenneth M. Jackson

Over recent years there has been a great deal of interest

in the way in which the U.S. Department of Defense has

installed and applied V.E. clauses in contracts with its

suppliers. This article describes the V.E. clauses in such-

contracts. It summarises the Armed Services Procurement

Regulation (Revision 23, Section 1, Part 17, dated 1st

June 1967) in an easy-to- understand form.

The author does a great service to British government and

industry in drawing attention to what value engineering

contractual incentives are and the kind of areas in which

they may be considered for application. He further offers

to reply to any inquiries from readers.

Through the ASPR V.E. provisions he says in the United

States 'a new profit center has been added to many

participating companies' and 'the pacing factor is

managerial ingenuity and commitment'. In the U.S. a vast

potential still exists for of the estimated $45 billion to be

spent in defense procurement in 1968 projected savings

only amount to $130 million or 0-3%.

I nt r oduc t i on

The purpose of this article is t o describe the value engineering

clauses used in U. S. Department of Defense contracts, and t o

suggest the use of similar provisions in Brit ain by bot h govern-

ment and indu stry procurement authorities.

Valu e engineering provisions are needed in order t o provide a

vehicle for the parties t o a contract t o optimise its value t o each

of them. They are part icu larly appropriate in 'sell-make' indus-

tries, such as constru ction, defense weapons, and other systems

producers. The need for value engineering became apparent in

1960 aft er reviewing the rate of increase of defense costs in the

preceding decade. To communicate this as a 'demand' for innova-

tions and challenges t o 'gold-plated' requirements, the Govern-

ment, even as a monopsonistic buyer, was forced t o offer rewards

(comprised of increased sales volu me t hrou gh higher technical

evaluation points in new procurements, higher profit abil it y of

defense contracts, and the like) before the sellers wou l d be wil l ing

t o seriously pursue value engineering.

The reluctance of sellers t o participate was based u pon the terms

of the standard 'changes' article of Defense contracts: ' I f any

change (t o the contract, ordered by the Cont ract ing Officer)

causes an increase or decrease in the cost o f . . . this cont ract . . .

an equitable adjustment shall be made in the contract price (or

fee) . . .' I n practice, then, an accepted value engineering-based

change proposal wou l d result in cost savings t o the government

as a consequence of the init iat ive of the contractor, bu t wou l d

also penalise the contractor by reducing his profit or fee originally

priced against the costs being eliminated. I n addit ion, the con-

tractor, by reducing expenses, lost part of the base which absorbs

* Mr Kenneth M. Jackson, Manager of Contracts,

DynalectronCorporation, Washington,D.C, U.S.A.,

has recently produced a book N e w AS P R V a lue

E ngi neer i ng P r ov i si ons (published by Sci-Tech

Digests Inc., 888 National Press Building, Washing-

ton, D.C. 20004). He holds the B.A. and J.D.

degrees from Southern Methodist University, is

Chairman of the Procurement Regulations Com-

mittee of the National Aerospace Services Associa-

tion, and a member of the American Bar. Permis-

sion of Sci-Tech Digests Inc. to publish this article

is gratefully acknowledged.

overhead costs. I n a word, there was an incentive not t o su bmit

cost-reducing change proposals. Of course, the fixed-price con-

tractor wou l d retain al l of any savings realised from value

engineering actions which did not require a change t o the con-

tract.

This practice fol l owed from the legal relations of the parties. I n

fixed-price contracts, a dol l ar saved is, generally speaking, a

dollar earned. I f the customer must approve a change in the

contract before the seller can take the action t o save that dollar,

the buyer must disregard his right t o demand performance

st rict ly in accordance wit h the contract or his alternative right t o

receive a part ial price refu nd for any deviation. I f he does not

wish t o exercise his right s; i f he wishes t o actively seek goods of

better qu alit y at lower cost, then he must motivate the seller,

who has a right t o fu l l payment for the supplies and services as

originally contracted.

Throu gh the use of value engineering clauses, the Government

buyer is able t o motivate the supplier t o submit cost-reducing

change proposals by providing profit increases for changes which

reduce cost. As a consequence, he has the opport u nit y t o optimise

the value of his purchase, and the seller may realise the opt imu m

economic ret u rn for his effort s. Yet this mu t u al it y of interest is

not the key point in the evalu ation of the effectiveness of the

incentive clauses. Today we are operating on the positive not ion

that as l ong as the Government can realise one dollar of savings

from the expected t ot al cost of bu ying and owning a weapon

system, no amou nt of reward payment t o the contractor wit hin

the range of t ot al cost minus $1 wou l d be exorbitant. Bot h parties

are in a better posit ion t han at the time of contracting, assuming

adequate probabilities of ret u rn.

I n addit ion t o the direct profit incentives, the contractor is

encouraged t o participate in value engineering by (1) giving the

successful contractor addit ional points in source selection evalua-

t ion, and (2) giving weight t o past performance in generating

value engineering savings in determining the ' going-in' or

negotiated profit or fee rate.

S u mma r y of t he Regulat or y P r ov i si ons

The Armed Services Procurement Regulation, Revision 23, Section

I , Part 17, entitled ' Valu e Engineering' may be divided int o t wo

parts. One provides statements of policy, and instructions for use

of the contractu al vehicle; the other provides standard clauses

t o be incorporated int o defense contracts.

Value Engineering, September 1968

135

P oli c y and P r oc e dur e s

The policy statements provide an accurate summary of the

objectives of the value engineering program. They include an

au thorisation t o purchase value improving ideas which are sub-

mit t ed as unsolicited proposals.

' Valu e Engineering' has as many definitions as practitioners. For

purposes of the defense contract, however, it is defined as an

effort t o provide the essential fu nct ion of an it em or task at the

lowest overall cost, which is embodied in a cost redu ction

proposal for changing the contract. The proposal is su bmitted

under one of t wo types of provisions, and may be originated by

either the prime contractor or by one of his subcontractors. The

first type of provision is called a ' Valu e Engineering I ncentive', in

which the level of value effort is entirely u p t o the contractor. The

costs of developing a change proposal are not allowable; i f

accepted, the development and implementation costs are deducted

from the gross savings before sharing. Under the second type, the

'Valu e Engineering Program Requirement', the Government

fu nds a level of effort , inclu ding loadings and profit . Sharing of

savings is, of course, reduced for the contractor under this clause.

The incentive clause, wit h several exceptions, is used in contracts

over ? 100,000, althou gh it may, wit h special ju st ificat ion, be

used in contracts under that amount. The program requirement

clause is used in cost-plus-a-fixed-fee, system definit ion, or other

contracts where the lack of firm specifications wou l d likely

render an incentive clause incapable of realising the savings

potential. Bot h types may be included in the same contract if

their application can be identified t o separate phases or portions

of the work.

The key probl em wit h bot h provisions is t o provide an opport u -

nit y for a ret u rn t o the contractor which substantially exceeds the

loss resulting from the decrease in volu me on present and fu t u re

contracts. The point varies, of course, between contractors, and

is a fu nct ion of volu me, compet it ion, type of contract, priced

profit , and so on. To provide a substantial base against which the

policy of increasing profit s by a ' fair proport ion' of saving is

applied, three types of savings are shared: (1) savings under the

instant contract, i.e., the contract under which the change propo-

sal was su bmitted; (2) savings in fu t u re or contemporaneous

acquisitions of the it em or task for a stated qu ant it y or time

period, either in a l u mp sum advance payment or on a ' royal t y'

basis, as additional units are procu red; and (3) savings in Govern-

ment operations (' Collat eral' savings). The proport ion of savings

paid t o the contractor varies as a fu nct ion of type of savings, type

of contract, and type of provision. The fol l owing chart sum-

marises these rates:

A . I nstant Contract Savings

Type of Clause

Type of Contract

Fixed Price

I ncentive Fee

Incentive

Range Norm

0-75% 50%

0-50% varies

according t o

overall cost

incentive and

accuracy of

savings

estimate

Program

Range

0-25%

0-25%

Cost-Plus-Fixed-Fee N / A 0-10

Norm

not stated

varies

according t o

overall cost

incentive and

accuracy of

savings

estimate

10%

B. Fu t u re Acqu isit ion Savings Range

1. Wit h I ncentive Clause

2. Wit h Program Clause

(a) Fixed Price and

I ncentive Contracts

(b) Cost-Plus-Fixed-Fee 5 % normal .

20-40% depending u pon period of

sharing.

10-20% depending u pon period of

sharing bu t not t o exceed share

under instant savings provision.

C. Collateral Savings Definit el y specified as 10%, except

that savings resu lting from a reduc-

t ion in the amou nt of Government

fu rnished material required under

the instant contract is rewarded at

the instant contract rate.

Payments made as a result of accepted change proposals are

treated in 1-1705.4 as 'payments for services rendered', and not as

profit or fee, which are subject t o statu tory limitations in cost-

reimbursable type contracts. Whil e earnings from value engineer-

ing are subject t o renegotiation (a process for obtaining refu nds

of excess profit s realised over al l government sales of the con-

t ract or), f u l l consideration is given t o the statu tory factors reflect-

ing the contractor's contribu tions, init iat ive, and risk. I f a change

proposal applies t o other Government contracts, whether or not

held by the submitter, he shares in the acquisition savings

realised under such contracts.

C ont r a c t C la u s e s

The same clause is used for bot h the incentive and the program

requirement methods, except that the latter references the stated

level of effort in the contract schedule and the mil it ary specifica-

t ion, MI L-V-38352, in accordance wit h which the program is

performed. The clause specifies the data t o be submitted wit h the

proposal, e.g., technical description and evaluation of the

proposed change and cost impact. The instant contract sharing

paragraph states the met hod of adju sting the contract price, costs

or fees in order t o vest the sharing payment, which varies between

types of contracts. Paragraph (e) provides the formu l a for arriv-

ing at the net savings amou nt on sub-contractor-originated

changes. Anot her paragraph provides that, while the contractor

may restrict the Government's use of the data su pporting the

change before acceptance, the Government receives f u l l rights t o

use and disclose the data u pon acceptance. Paragraph (i) defines

'instant contract' in cases where there are options, increases in

contract scope, and indefinite ordering arrangements. Then fol l ow

the clauses for bot h types of fu t u re acqu isition savings wit h their

detailed formu las for compu t ing savings and sharings.

Not es C onc e r ni ng S pe c i a l P r ov i si ons

Of interest t o the general reader are the fol l owing notes. Refer-

ences are t o the paragraphs of the Armed Services Procurement

Regulation.

1-1701. Valu e engineering is not l imit ed t o improvements in

hardware. The ASPR committee clarified this in Revision N o. 23

by referring t o the redu ction of cost in 'any contract it em or

task'.

1-1702. A change proposal is acceptable even i f it causes the

deletion of contract line items. However, the contractor wil l not

share in savings resulting solely from qu antitative evaluations of

defense requirements.

1-1703(b). I n negotiating sharing rates, this paragraph reminds

the parties, it is the Government's policy t o provide strong

financial incentives for maximu m effort in value engineering.

Deleted from prior regulations is the addit ional test which

provided that the Defense Department wou l d be generous in

sharing only if it cou l d be assured of definite cost redu ction sav-

ings. Because of the accomplishments of V. E. , it is wil l ing t o take

reasonable risks by payment of shares before savings are 'assured'.

1-1703.2(f). Cost savings t o be shared are calculated as fol l ows:

1. Tot al decrease in contract price (or target cost); minus

2. Contractor's costs of developing the value engineering change

proposal, provided (a) they are properly direct charges under

the contract involved, and (b) they are not otherwise reim-

bursed t hrou gh either program requirement fu nding or

ASPR Section XV (Cost Ru les); minus

3. Contractor's cost of implementing the change.

'Development Costs' are those costs incu rred after the contractor

has identified a specific value engineering project. 'Contractor's

implementation costs' are the costs of incorporat ing a change

which are incu rred after acceptance of a change proposal.

1-1703.3. The period of time for sharing of savings on purchases

made in the fu t u re shall be sufficient, wit hin the stated l imit s, ' to

induce a significant value engineering effort ' .

1-1703.4. Collateral savings wil l be shared net of any change, up

or down, or wit h no change in acqu isition costs.

l-1704.2(c). Provides, as does its corollary, paragraph (f) of the

basic clause, that the amou nt of collateral savings determined by

the contracting officer is u nilat eral. The amounts of present and

136 Value Engineering, September 1968

fu t u re acquisition savings are subject t o negotiation and settle-

ment procedures.

1-1705.2 Where a single change proposal substantially affects the

basis for compu t ing performance incentives in a mu lti-incentive

contract, an equitable revision wil l be made in the performance

provisions. Experience t o date indicates that value engineering

change proposals enhance performance, so that incentive profits

are increased as wel l . However, there may be degradations in

incentive profit elements where it wou l d be desirable t o reduce

performance targets.

1-1705.3. Advance consideration should be given t o the treatment

of al l types of costs t o be incu rred in implementing a value

engineering clause, e.g., testing costs. Al l owabl e costs incu rred are

allowable as indirect charges except t o the extent they must not

be charged, bu t only deducted from gross savings in accordance

wit h l-1703.2(f). The costs may not be charged direct, except in

the case of the program requirement clause, and then only t o the

extent proper t o cover the required program.

1-1707. Basic Clause Paragraphs.

The Valu e Engineering Change Proposal contents specified by

paragraph (b) shou ld be supplemented by addit ional 'sales'

language, and the contractor ought t o specify the du rat ion of his

offer, whether it is ' al l or none', and he may wish t o protect his

data rights in accordance wit h paragraph (h).

Whil e 1-1703.1(a) states that expeditious processing of change

proposals is an essential element of an effective incentive, para-

graph (c) (1) states that the government shall not be liable for any

delay in action on a proposal. The decision as t o acceptance of a

proposal is final and is not subject t o the 'disputes' clause.

Paragraph (c) (2) provides that the contracting officer may accept

a Valu e Engineering Change Proposal by issuing a change order

t o the contract. A change is a u nilateral document when issued,

and the contractor must comply. Onl y then can negotiations take

place, and the change order superseded by a bilateral contract

amendment. I f the parties are unable t o agree on amou nt or other

terms of the proposal, a disputes remedy may be available.

However, Paragraph (c) (2) also provides that the contracting

officer may accept the Valu e Engineering Change Proposal in

whole or in part. Only if the proposal is condit ioned t o require

acceptance on an ' al l or none' basis wou l d any part ial acceptance

or any acceptance varying the terms of the offer in such a manner

as t o constitute a counter offer be improper.

The final sentence of paragraph (e) states that, whil e payments of

shares t o sub-contractors may be treated as part of the sum of

development and implementation costs, the Government's share

on addit ional purchases may not be reduced by such payments.

Consequently, special attention t o sub-contracts wit h Valu e

Engineering incentives is needed t o achieve a balance of mot iva-

t ion of the sub-contractor and compensating ret u rn for the

volu me decrease realised by the prime. The problems of cost

allowabilit y, met hod of charging, and adequate ret u rn are

part icu larly troublesome in this sub-contracting area, which

constitutes a significant port ion of the procurement dollar and

savings market.

Paragraph (f) (2), apart from its literal provision, is intended t o

compensate maintenance, overhaul and repair contractors when

the end it em is a u nit of serviced Government equipment, rather

than a u nit of hardware, at the higher sharing rates. Otherwise

the contractor wou l d be l imit ed t o sharing at the ten per cent

collateral savings rate.

Under paragraph (g), instant contract sharing is permitted under

more t han one contract, whether held by the submitter or another

contractor, except that collateral and fu t u re savings are shared

only under the contract under which the proposal is first received.

Obviously, the contractor shou ld evaluate sharing calculations

under al l affected contracts in order t o determine under which

contract a proposal shou ld first be submitted.

C onc lus i on

I t is hoped that the reader of ' Valu e Engineering' has now

acquired a knowledge of why value engineering contractu al

incentives are needed and a flavour of the clauses and provisions

used in the U. S. Department of Defense t o fill the need. As a

novice in the ambience of Brit ain' s government procurement, it is

recognised that wholesale application of the U. S. provisions t o

its contractors l ikel y wou l d encounter serious difficu lties. A t the

same t ime, ou r experience is that init ial reactions of government

and indu stry t o the effect that 'value engineering incentives are not

applicable t o my area of interest' are proven t o be incorrect.

Today even ou r Post Office Department is using value engineer-

ing. Some companies having design cont rol offer incentives t o

sub-contractors even where no incentives are payable t hrou gh

prime contracts. The writ er wil l be glad t o respond t o any

inquiries forwarded t hrou gh the editor.

I n the Unit ed States, a vast potential st il l exists. Of the estimated

$45 bil l ion t o be spent in defense procurement in fiscal year 1968,

projected gross savings from contractor-originated change

proposals before sharing amou nt t o $130 mil l ion annu ally or

only 0-3 %. Savings in the magnitude of upwards of 1 % of the

defense dollar are readily projected, and 10 % is not an impossible

goal. Approximat el y fort y percent of the gross savings is paid t o

contractors. A t a profit rate of 10%, this is the equivalent of hal f

a bil l ion dollars in sales, a substantial market.

I n short, a new profit center has been added in many part icipat ing

companies. The contractu al incentives provide a u niqu e opport u -

nit y for joining the conflict ing interests of each part y t o defense

contracts; opt imu m economic ret u rn and maximu m usable

mil it ary ou t pu t . The pacing fact or is managerial ingenu ity and

commitment.

Miscellany

T h e P e r g a mon P r e s s

Pergamon Press was fou nded joint l y in 1948 in London by

Bu t t erwort h & Co. (Publishers) Lt d. one of the oldest pu blishing

houses in England (established circa 1600), and by Springer-

Verlag of Heidelberg and Berl in, the leading Eu ropean scientific

pu blishing house, under the t it l e Bu tterworth-Springer Lt d.

A change of share ownership in 1951 made it possible t o change

the name t o PERGA MON PRESS.

Pergamon was the name of a Greek t own m Asia Minor, famou s

for one of the great works of art, the A l t ar of Pergamon,

dedicated t o At hena. The PERGA MON PRESS colophon is a

reprodu ct ion of a coin fou nd at Herakleia, dat ing from about

400 B. C. , showing the head of At hena. At hena is recognised as

the presiding divinit y of states and cities, of the arts and indus-

tries - in short, as the goddess of the intellectual side of hu man

l ife.

R e d u c e s dr ag by 40 per c e nt

As l it t l e as one part per mil l ion of Polyox in water reduces drag

by 40 per cent.

Polyox resins are widely used in adhesives, hair sprays and

toothpaste. The Polyox solu t ion is viscoelastic. Chemically it is a

l ong chain polymer of ethylene oxide.

When it is stirred it 'rebounds' after coming t o rest and starts t o

move in the opposite direction.

I t flows u phil l . Once the flow is started by t ipping the beaker

containing Polyox solu t ion it continues l ike a siphon wit hou t a

tube t o contain it . The siphon effect does not always empty the

beaker. The height the l iqu id wil l cl imb u p inside itself depends on

how far it falls outside. To empty a beaker containing fou r litres

(a bit less t han a gallon) Dr D. F. James of the Cal ifornia I nst it u t e

of Technology fou nd he needed a fal l of eleven feet.

Value Engineering, September 1968

137

E

LED BY

I

C Eng, AMI Mech E, MIMC

have

increased prof its

reduced costs. ....

improved saleabilrty

for l eadi ng compani es in

motor vehi cl e manuf act ur e

el ectri cal engi neeri ng

hydraul i cs

machi ne tool s

el ectroni cs

offi ce equi pment

i nst rument at i on

consumer durabl es

manuf act ured j oi nery

and many other i ndust ri es

Teams composed of Sales/

Market i ng, Product i on, Desi gn

and Purchasi ng, i ncl udi ng at

least one top manager, bri ng one

of thei r own product s f or study

Realistic savi ngs usually exceed

20% of product costs

TH E TACK ORGANISATION

_ LONGMOORE ST LOND ON SWI

TELEPH ONE: 01-834 5001

Cost

Reduction

Essential

for

Industrial

Survival

Value Analysis is the most powerful management

tool yet devised in the fields of cost reduction, cost

awareness and design.

Value Analysis is a textbook for all levels of

management in industry, intended as a reference to

the fundamental principles of Value Analysis/

Engineering. Written by John Gibson, Value

Engineering Manager, Osram (GEC) Limited.

This book covers the main features of Value

Analysis:

1. Costhow it is initiated.

2. Unnecessary costhow it is caused.

3. The concept of value.

4. How to obtain equivalent quality and perform-

ance, at a lower cost.

This book is a must for all involved in design,

planning and decision-making, where cost control

and reduction is needed.

Reduce your costs: Fill in and mail this slip today

To: Promotions Manager,

Training & Technical Publication's Division,

Pergamon Press Limited,

Headington Hill Hall.

Oxford.

Please send me. . copies of Value Analysis,

price 21 s.Od.

Name-

Address.

138

Value Engineering, September 196K

Reprint No. 1:3:3

Creativity - Value Standards

The Constraints to Creative

Value Engineering

by Lt. Colonel Bert Decker

In this second article. Colonel Decker aptly quotes the

Assistant Secretary of Defense's reference to value

engineering as a 'rebellion from beneath'. The purpose of ,

every rebellion is to overcome some organised constraints '

and the author goes on to show how managers may

improve individual creative behaviour and optimise group

creativity.

Problems in the main yield best to interdisciplinary

innovative efforts which are constrained in various ways.

Colonel Decker, as well as describing these constraints -

habitual, semantic, educational, and so on - offers sug-

gestions for overcoming them.

Whilst not knowing of the creative techniques is a con-

straint, knowing of them does not eliminate the constraint

unless one knows when and where to use them. People,

too, are attracted in differing degrees to the various

techniques.

The need for a definition of value couched in verifiable

measurable terms is urged for managers cannot effectively

manage and control that which they do not clearly under-

stand.

Differentiating between 'competitive' and 'integrated

cooperative' value engineering the author refers to the

failure of the former in the long run. Integrate value

engineering into the organisation; teach those inside so it

is they who cut costs and simplify design.

G.E., over a three-year period, saved $25.75 for every

dollar spent on value engineering but-as an additional

benefit - they reduced engineering development time by

25per cent. Achievements like this come from the creation

by management of a climate that is conducive to the

application of value engineering principles.

When one considers the constraints t o creative value engineering,

one wonders how it ever happens. To some extent, resistance

t o creative attempts seems t o be bu il t int o man's genes. However,

it is the dynamic apathy and myopt ic negativism which has

retarded value engineering for t wo decades that convinces one

that t radit ional firms are u nfort u nat ely most efficiently organised

t o cause bot h unnecessary costs and detrimental conformit y. I n

fact , one must evaluate value engineering as creative solely on the

basis of its persistence. I n spite of its many constraints, it persists

and accelerates.

The many and complex constraints t o the profit able innovat ion

concerning value derive from many sources. Edu cat ion inculcates

them, t raining shapes them, and organisations bu il d constraints

t o creative activities int o their procedures. However, the greatest

barrier t o increasing value is ou r own habit u al verbal patterns

and ou r own unconscious, erroneous assumptions concerning how

t o achieve indu st rial innovat ion.

The Honorable George Fou ch, Assistant Secretary of Defense,

has correctly called Valu e Engineering a ' rebellion from beneath'.

I t was a shrewd, int u it ive observation which makes one realise

that we must somehow change Valu e Engineering int o a 'creative

crusade by chiefs'.

The purpose of every rebellion is t o overcome some organised

constraints. I n the indu st rial worl d, 'organised constraints'

shou ld be very mu ch the concern of managers. I n fact , in their

complex, over-specialised environment, their most pressing prob-

lem concerns the opt imisat ion of the grou p creative behaviour of

* Colonel Decker, USAFR (Ret.) is Director of

Project 3000 at the State University of New York at

Buffalo. He wrote on 'The Creative Aspects of

Value Engineering' in the first issue of the journal.

His address is c/o Office for Continuing Education,

Millard Fillmore College, State University of New

York at Buffalo, Hayes A, 3435 Main Street,

Buffalo, N.Y. 14214, U.S.A.

their subordinates. I mproving the creative behaviour of an

individu al is relatively easy in comparison t o opt imising creative

cooperation. Valu e Engineering is very mu ch a grou p act ivit y.

That , in itself, is a constraint. Today's problems are interdiscipli-

nary. Few can be solved by one man alone. I nterdisciplinary

integration and innovat ion is the obvious answer and pressing

need. Profits derive from creative change. The average indu st rial

produ ct rarely remains unchanged for more t han three years.

The constraints t o creative value engineering and the interdisci-

pl inary innovat ion which it strives t o be can be classified under

five general headings as fol l ows:

1. Habit u al hu man responses deriving from bot h evolu t ionary

and indu st rial survival factors.

2. The General Semantics difficu lties involved and the inabil it y t o

resolve them.

3. Lack of understanding in and practice of the creative concepts

and techniques and especially the inabil it y t o optimise grou p

creative behaviour.

4. Lack of understanding of value engineering and especially of

why it is different, radical, and difficu l t t o manage.

5. Lack of understanding of how education, t raining, and daily

indu st rial practices shape conformit y rather t han creative

behaviour.

Habi t ual C ons t r a i nt s

I n ' The Creative Aspects of Valu e Engineering', it was stated

that man is instinctively creative in that al l of l ife rebels against

its harsh environment and attempts t o change it . Creative rebel-

l ion does seem t o be a characteristic habit of al l creatures. How-

ever, another almost instinctive habit which characterises man

seems t o negate effective creative behaviour as defined today.

That constraint can be called the ' swift habit u al signal response'.

The ' swift habit u al signal response' is an automatic, instanta-

neous, discriminative, manipu lative, evaluative reaction to danger

or threat of danger in the environment. I t is deeply ingrained

since it is a su rvival produ ct. The caveman who instantaneously

discriminated the spot of yellow in his green ju ngle manipu lated

Value Engineering, September 1968

139

it in his cerebric memory banks, evaluated it as the Sabre

Toot hed Tiger, and au tomatically ju mped for the nearest tree,

survived. Because he survived, he gave that capability t o instan-

taneously discriminate, manipu late, evaluate, and react t o his

children. Down t hrou gh the ages that swift , habit u al signal

response has been perfected. I t is almost a reflex action. Korzybski

warned us about that 'signal response'. Al ex Osborn gave us

techniques for overcoming it .

The swift habit u al signal response was and st il l is a su rvival

necessity. We must react instantaneously t o some dangers.

Fortu nately, however, the caveman discovered that a fire at the

cave door kept the tiger ou t and gave man time t o t hink. The

bow and arrow, however, which he created t o reduce the danger

of the large cat was not the result of a swift habit u al signal

response. I t was a produ ct of extended creative effort . I t was

developed slowly. The sharp stone came first. Fastening it t o a

branch fol l owed and the new u niqu e combinat ion was used as a

spear. Mu ch later came that u niqu e set of verifiable fu nct ions

provided by that weapon system called the bow and arrow. The

extended creative behaviour of many men produced it .

I n the economic ju ngle, the greatest danger is the boss. He is

today's Sabre Toot hed Tiger. I t is his whim, his fancy, his words

that subordinates instantaneously discriminative, manipulate,

evaluate, and react t o. Unfort u nat el y, that swift habit u al signal

response t o the words of the boss is not very creative. Bu t he,

being hu man, likes it . I t becomes even more of a habit.

I n economic l ife, managers are for the most part a self-elected

elite. Managers pick managers; few stockholders bother t o use

their vote. This means that every ambitious subordinate studies

the behaviour of his boss, apes it t o a large degree, uses the values

of the boss as evaluative criteria and, in general, reacts in a

manner that keeps the boss happy. Thu s ou r economic l ife is

organised t o shape excessive detrimental conformit y. Effective

managers cl aim they want no 'Yes-men' bu t st ill tend t o be the

victims of their most persuasive specialists who t el l t hem what

those managers want t o hear. Nat u ral l y such conformit y negates

the innovat ion u pon which modern organisations t hrive and

wit hou t which they stagnant. We hear mu ch of 'permissive' and

' part icipat ing' management bu t not in scientific terms. We

flou nder towards the solu t ion.

S e ma n t i c Di f f i c ult i es

Today's 'swift habitual signal responses' are mostly verbal. People

skilled in General Semantics call them ' Conventional Wisdoms'

or ' u nverifiable generalities'. Others, skilled in the detection of

propaganda, call t hem ' glit t ering generalities' because they

' sou nd' so good bu t mean so l it t l e. They include such statements

as ' The effective leader is a professional manager' or ' The effective

manager must, at al l times, ret ain a safe margin of psychological

distance while part icipat ing wit h subordinates'. One finds no

verifiable fu nct ions in such statements. Scientifically, they are

meaningless. They cannot be verified as either true or false. Their

onl y ju st ificat ion is that they aid and abide economic su rvival.

They please managers because they ju st ify and reinforce manager

behaviour. Managers l ike being called 'professional'. I t sounds

impressive.

Managers interested in having innovat ion happen and value

increased must be very mu ch aware of these habit u al constraints

called the swift , habit u al, signal response, conventional wisdoms

and glit t ering u nverifiable generalities.

As covered in 'the Creative Aspects of Valu e Engineering', the

greatest constraint t o creative behaviour is semantic. We assume

and operate u pon the erroneous assumptions that the word is the

t hing and that a word has meaning by itself. I n fact, research wit h

six-grade children has demonstrated that Korzybski-t ype t raining

in General Semantics increased their verbal flexibility and fluence

bot h of which influence creative behaviour.

The need for semantic clarificat ion in ou r dialogues concerning

indu st rial organisation, management, decision-making, problem-

solving, etc., is obvious. Such dialogues are almost completely

void of verifiable fu nct ions. Words such as au t horit y, responsibi-

lities, and decision have yet t o be defined in scientific terms. This

does'not say that they wil l not be. For instance, it is possible and

might be highly advantageous t o define a decision as a verifiable

statement; i.e., a verifiable set of verifiableTunctions which has a

tendency t o evoke behaviour which increases or decreases

verifiable value.

Unfort u nat el y, far t oo few indu st rial people have had adequate

t raining in General Semantics althou gh some corporations have

published excellent papers on the subject for their people.

I gnor anc e C onc e r ni ng C r eat i v e C o n c e p t s

The worl d abounds wit h intuitively creative people. Far t oo few

are deliberately, consciously creative in accordance with creative

rules. Many erroneously consider lack of discipline as creative

and associate creative behaviour wit h u niqu e, different, 'screw-

bal l ' behaviour only. However, creative behaviour must be bot h

unique and profitable. To be creative, it must increase value. To

creatively increase value requires a u niqu e creative discipline, a

discipline which consistently fol l ows creative rules in a con-

sistently flexible manner. I t is behaviour disciplined t o be

habit u ally u nhabit u al in extended creative effort . Fu rther, many

people pay ' l ip service' t o the creative concepts they know. Like

Christian principles, the creative guides for action may be known

bu t not practised.

N ot enough creative concepts have been stated in scientific terms.

However, some creative guides for action have been research-

proven. Al ex Osborn's principles concerning 'deferred ju dgment'

and that ' qu ant it y breeds qu alit y' have been proven by research.

I f people do defer ju dgment, crit icism, and evalu ation at first, it

can be demonstrated that there is a significantly high degree of

probabil it y that they wil l generate a bigger percent of ideas which

they themselves evaluate as 'better'. ' Deferred ju dgement' also

increases value as value engineering has demonstrated time and

t ime again. The fact that creative behaviour has only recently

been defined in verifiables is very definitely a significant constraint

t o creative value engineering.

The fact that creative concepts have not been research proven

does not necessarily negate their usefulness. I t is u sefu l t o know

that the creative process is advantageously defined as a cyber-

netic 'feedback' system of ' Object ive-Finding' , ' Fact -Finding' ,

' Problem-Finding' , ' I dea-Finding' , ' Sol u t ion-Finding' , and

'Acceptance-Finding'. Creative techniques such as the 'Forced-

Relationship Technique', 'Synectics', Bionics', the ' Catalog

Technique', etc., al l obviou sly generate divergent behaviour and

exploit the research proven principle of ' Qu ant it y breeds

Qu al it y' .

N ot knowing of a creative technique is a constraint bu t knowing

of a technique does not eliminate the constraint unless one knows

how and where t o use it . Fu rther, because many creative guides

for action are not stated in scientific terms, bu t instead in very

vague terms, many fail t o understand them. The advice t o ' Think

Big' or 'Broaden the Scope', for instance, leave a l ot of people

cold, yet those statements evoke a l ot of creative behaviour from

others. Fu rther, ju st because people have been taught the value of

' l ooking at the advantages of an idea before even considering the

disadvantages' does not mean they wil l do so.

V a lue E ngi neer i ng I gnor anc e

Du ring the American Civil War there was an attempt t o sell

repeating rifles made on a mass-production basis t o the U.S.

A rmy. The A rmy wou l d have no part of it for t wo reasons. Their

addit ion indicated that they cou l d not logistically support

rifles being fired that fast! Second, they were afraid that if one

man did not make the complete rifl e there would be no pride in

craftsmanship. Hist ory has demonstrated that their first reason

was nonsense bu t their second does indeed have some ju stifica-

t ion.

Prior t o mass-production, the manager's job was simple. He hail

one man under him, the craftsman, responsible for the value of

the produ ct. I f that craftsman did not produce an it em the

manager cou ld sell at a profit , he either changed the behaviour of

the craftsman or fired him.

Wit h mass-production and its specialisation of tasks, the mana-

ger's value problem became completely ou t of hand. Everyone on

the produ ct ion line directly influenced the value of the product.

I n addit ion, every other part of the organisation either directly or

indirectly influenced the value of the produ ct or else we cou ld not

140

Value Engineering, September 196H

ju st ify their existence. Wit h everyone being responsible for value,

no one is. Wit h no way for the manager t o measure the degree of

influence that each department had u pon the value of the produ ct,

he soon became the vict im of his most persuasive specialist. I n

fact, u nt il twenty years ago, he had no way t o precisely measure

value for the simple reason value had not been defined in verifi-

able measurable terms. Few managers are aware of the opport u -

nities which the value concepts gives them. Their ignorance of

those opportu nities does constrain value engineering.

When Valu e Engineers first asked ' What causes unnecessary

costs?' they fou nd that the list was long. These constraints t o

value and the creative effort requ ired t o increase it inclu ded such

things as split au t horit y, split responsibilities, failu re t o use avail-

able specialists, excessive over-specialisation, Empire Bu il ding,

Selfish Sectional Efficiency, knowledge hoarding for power's

sake, lack of effective coordinat ion, lack of grou p creative plan,

lack of ideas, and excessive conformit y. Valu e Engineering is

actually a creative, systematic organised attempt t o overcome

these organisational discrepancies and constraints. As noted

above, their attempts t o overcome those organisational con-

straints have been called a ' rebellion from beneath', for the simple

reason that those constraints come under the ju risdict ion of

middle management. N ot understanding the purpose, techni-

ques, or promise of that ' rebellion' , middle managers int u it ivel y

counter attacked. Besides, the more successful value engineering

is, the more middle management looks bad. Looking bad is not

conducive t o economic su rvival.

The swift habit u al signal responses and conventional wisdoms

generated in reaction t o successful value engineering st il l fill

today's engineering and management literatu re. ' Valu e Engineer-

ing is ju st good engineering under a new name!' is heard t oo

oft en. Those making such statements cannot define ' good

engineering' in verifiables and overlook the advantages of being

able t o so define 'value'. The statement that ' Ou r System Cost

Effectiveness people eliminate al l unecessary costs before design'

overlooks the fact that System Cost Effectiveness has been based

u pon t radit ional cost analysis which value engineering has

demonstrated as inadequate for determining precise value.

I gnorance is always a constraint. I t is an erroneous assumption

that managers can effectively manage and cont rol that which they

do not understand. Knowing the value concepts is not enough.

Managers must understand the implications of those concepts,

their impact u pon the t radit ional organisation, the degree t o

which those concepts are in conflict wit h what al l of us call 'the

stu pid system', the shaper and creator of 'the organisational man' .

The most import ant lesson learned from the list of organisational

constraints which cause unnecessary costs is that t radit ional

organisation is very effectively established t o cause t hem and

excessive detrimental conformit y. Fu rther, they are creative clues

for those imaginative managers who are interested not onl y in

overcoming those constraints bu t in eliminating them.

One of the greatest retardation factors t o value engineering over

the last twenty years has been 'competitive value engineering' in

contrast to.'integrated cooperative value engineering'. ' Compet i-

t ive value engineering' is when a team from outside an organisa-

t ion or division goes in and does that u nit' s value engineering

task. To do this, they must ' pick the brains' of those in the

organisation, go t hrou gh their files and in general waste their

time. However, because they use the V. E. techniques, they

invariably drastically reduce costs and simpl ify design. I n fact ,

they usually make the original design l ook l ike a Ru be Goldberg.

This nat u rally shatters the self-image and self-confidence of those

in the organisation who were responsible for the original design.

Worse st il l , it threatens their su rvival capability in the economic

ju ngle. They nat u rally react against bot h the outsiders and value

engineering.

Time and time again in American corporations, ' Competitive

Valu e Engineering' has started ou t wit h startling profit able results

and slid slowly t o a complete halt. The second time arou nd the

insiders ju st do not allow their brains t o be picked. Records can-

not be fou nd. Protective tactics dominate. Reactive rationalisa-

tions take over. Valu e engineering becomes 'ju st good engineering

under a new name!' Soon everyone goes back t o ' good engineer-

ing' and doing things in the ol d t radit ional wastefu l way.

The tactic t o overcome 'competitive value engineering' is simple.

Do not do it . I nstead, integrate value engineering int o the

organisation. Teach the insiders so they cut costs and simpl ify

design. Most import ant , start from the t op down and teach the

managers t o value engineer so they understand its implications

and can creatively exploit its profit able possibilities. Fu rther,

blame the original ' Ru be Goldbergs', the fau l t y designs and al l

the waste in the past u pon the ' st u pid system'. Do not blame any

one person. To do so stops value engineering cold. Reinforce the

new creative behaviou r: blame the system for past mistakes.

Blame and crit icism stifles creative behaviour.

The need t o integrate value engineering int o the organisation does

not negate the need t o have a small grou p in the organisation

devoting f u l l t ime t o insu ring that value engineering is planned,

fu nded, manned, and does happen. Fu rther, the Valu e Manager

must be u p close t o the t op manager or it ju st doesn't happen.

J Time is nat u rally a constraint t o creative value engineering t o

some degree as it is t o any creative effort . I t is because we t hink so

slowly that creative effort must be extended. However, value

engineering is noted for saving time in relat ion t o t radit ional design

practices. For instance, a Vice-President of General Electric

Company reported that not only did GE save $25.75 for every

dollar spent on value engineering over a three-year period bu t , as

an addit ional benefit, they also reduced engineering development

time 25 %. This, of course, is because value engineering does not

have the designer working al l alone and forced t o do a l ot of

research t o optimise his design. I nstead, the designer is provided

wit h a team of experts, a fast informat ion gathering team, who

either have the required informat ion in their heads or know whom

t o phone for it .

One bit of ignorance concerning the creative u t ilisat ion of time

is a constraint t o value engineering or any other type of problem.

Too many people solve problems sequentially. I f they have five

problems t o solve in a week, they attempt t o solve one a day.

This allows t hem t o incubate only one day on each problem.

However, i f they spent an hou r and a hal f on each probl em on

each day thus giving themselves five days t o incubate and extend

creative effort on each problem, the improved qu alit y of their

solutions wou l d amaze them. Students in creative problem-

solving courses have demonstrated this t o themselves t ime and

time again.

Example of ignorance of value concepts constraining the value

effort abou nd in indu stry. One fol l ows.

I n a large American electronic firm it was decided t o hire three

Valu e Analysts for the Procurement Department. They were t ol d

that their task was t o 'challenge al l requisitions and ascertain

whether a better, less expensive it em t han that ordered cou l d be

purchased'. Two did ju st that and nat u rally saved a l it t l e money

bu t the t hird didn' t ; in fact , the t hird cou l d be rarely fou nd in the

Purchasing Department, so three months later the head of

procurement fired him.

The firing of procurement's t hird Valu e Analyst caused an u proar

in, of al l places, the Design Department. Three Design Engineers