Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Anderson Kumar 2006

Hochgeladen von

heman_tCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Anderson Kumar 2006

Hochgeladen von

heman_tCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

Emotions, trust and relationship development in business relationships:

A conceptual model for buyerseller dyads

Poul Houman Andersen*, Rajesh Kumar 1

The Aarhus School of Business, Department of Management and International Business, Haslegardsvej 12, 8210 Aarhus V, Denmark

Received 3 May 2003; received in revised form 4 August 2004; accepted 7 October 2004

Available online 1 July 2005

Abstract

Existing research on buyer seller relationships has focused on the role played by trust in shaping the dynamics of interpersonal

interaction between the buyer and the seller. While this is undoubtedly an important variable in governing the interactional dynamics it is by

no means the only variable. The paper begins by reviewing the existing literature on buyer seller relationships. The role played by emotions

is articulated. Finally, it is recognized that the emotions that emerge in a buyer seller relationship do so at multiple levels. A model and

propositions highlighting the impact of emotions on interpersonal relationships are developed. Illustrative cases are used to ground the

propositions empirically.

D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Marketing relationships; Emotions; Inter- and intra-group behaviors; Business negotiations

1. Introduction

It is widely recognized that personal relations play an

important role in business-to-business (B2B) marketing.

A lack of a positive personal chemistry is an often-cited

reason for why business relationships either fail to

develop and/or fail to be sustained over time. The idea

that emotions play an important role in business relationships is also a theme that is also widely reflected in the

marketing research literature. In B2B literature, interpersonal dynamics determine the fate of many buyer

seller activities (e.g., Brierty, Eckles, & Reeder, 1998;

Coviello, Brodie, & Munro, 2000; Geyskens & Steenkamp, 2000; Keillor, Parker, & Petijohn, 2000). A

number of studies have highlighted the role played by

emotions in marketing channel relationships (e.g., Geyskens, Steenkamp, & Kumar, 1998).

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +45 89 48 66 30; fax: +45 89 48 61 25.

E-mail addresses: poa@asb.dk (P.H. Andersen),

rku@asb.dk (R. Kumar).

1

Tel.: +45 89 48 66 30; fax: +45 89 48 61 25.

0019-8501/$ - see front matter D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.10.010

Compared to one-off transactions, business relationships

are contingent on recurrent personal interaction among

individuals from both the buying and the selling organizations. The interaction is critically influenced by (a) the

actors behavioral modes of interaction, i.e. whether they

behave in a cooperative or a non-cooperative manner; (b)

actors perceptions of their counterparts trustworthiness; and

(c) the behavioral dynamic that emerges from the actors

perceptions of each other and the behaviors exhibited by

them towards their counterpart.

Most of the research on buyer seller relationships has

focused on the role played by trust in shaping the

dynamics of interpersonal interaction between the buyer

and the seller. While this is undoubtedly an important

variable in governing the interactional dynamics it is by no

means the only variable (e.g., Barry & Oliver, 1996;

Kumar, 1999). It is now increasingly being recognized that

emotions play a crucial role in mediating the dynamics of

interpersonal interaction (e.g., Kumar, 1997; Lawler,

2001). It is also worth noting that existing conceptualizations of trust in the literature view trust primarily from a

cognitive/rationalistic viewpoint and in doing so ignore the

more expressive aspects of human interaction (Anderson &

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

Narus, 1990; Spekman, Isabella, MacAvoy, & Forbes,

1996). A focus on cognition alone is insufficient as trust is

inherently emotional (Jones & George, 1998). Narratives

from business life demonstrate that mutual adaptation and

the development of trust often occur without a calculative

frame in mind (Wicks, Berman, & Jones, 1999). A lack of

personal chemistry or negative emotions may also

prolong trust building or terminate relationships. This is

frequently cited as an important aspect in marketing

alliance failure (Bruner & Spekman, 1998; Tully, 1996).

A particularly dramatic example of the role played by

negative emotions can be found in the break up of the

alliance between Meiji Milk and Borden (Cauley de la

Sierra, 1995). Although the relationship between the

companies had existed for over 20 years it became

increasingly acrimonious with the American firm Borden

accusing the Japanese partner of deliberately wrecking the

relationship.

Positive and negative emotions shape actors behavior

while simultaneously conditioning their perceptions of

trustworthiness of each other. In other words, emotions

play a crucial role in the initiation, the development and the

sustenance of relationships over time. The existing literature

has for the most part dealt with the role played by emotion

only superficially, and only limited attempts have been

made to conceptualize how emotions influence the development of buyer seller relationships. It is the objective of this

paper to remedy this gap in the literature. The paper begins

by reviewing the existing literature on buyer seller relationships. Then, the role played by emotions is articulated. The

central argument is that emotions influence the development

of trust with trust influencing subsequent interaction. It is

also noted that emotions may have a direct impact on the

behavioral interaction, irrespective of their impact through

the mediating mechanism of trust. Finally, it is recognized

that the emotions that emerge in a buyer seller relationship

do so at multiple levels, namely, the individual, the

intergroup and the interorganizational levels. A conceptual

model and a set of propositions highlighting the impact of

emotions on interpersonal relationships are developed.

Illustrative cases are used to ground the propositions

empirically.

2. Business relationships: a review of the literature

A major theme in the emerging literature on business

relationships is that relationships provide companies with

the opportunity of joint value creation either through

rationalization and/or learning. In order to reap these

benefits companies must collaborate and this invites the

possibility of opportunism on part of ones partner. The fact

that ones partner in the process of collaborative activity

may exploit one makes the decision-makers somewhat

cautious. This tendency is exacerbated in relationships

where the business partners must learn about each others

523

activities and share proprietary knowledge. The mixed

motive character of many of these relationships shapes the

way that the partners behave, the judgments that they form

about each other, and the overall commitment they

demonstrate in the relationship.

Scholars working in the field of business relationships

have highlighted the importance of interpersonal trust in the

initiation, the development and the sustenance of these

relationships (e.g., Andersen, 2001; Cova & Salle, 2000;

Witkowski & Thibodeau, 1999). Trust implies a high level

of confidence among ones partner (Das & Teng, 1998) and

for that reason is likely to lessen the need for excessive

contracting and monitoring (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Trust is

also likely to be associated with a high level of psychological commitment to the relationship among the partners

(Kumar & Nti, 1998). One implication of this is that the

level of effort put in by the partners in maintaining and

deepening the relationship will be of high quality. Finally,

trust is also likely to promote flexibility and adaptability and

in doing so it may strengthen the relationship between the

cooperating firms (Arino, dela Torre, & Ring, 2001). Most

studies on trust in interfirm relationships define trust as the

extent to which a firm believe that its exchange partner is

honest and/or benevolent (cf. Geyskens et al., 1998).

Conceptually honesty and benevolence are distinct: While

benevolence concerns the belief that ones partner is

genuinely interested in ones welfare and seek joint gains

from that basis, honesty concerns the belief that ones

partner is reliable, i.e. fulfils promised role obligations

(Anderson & Narus, 1990). Even though honesty and

benevolence are conceptually distinct, they are typically

analytically inseparable, and emotions are expected to load

equally on shaping business partners perceptions of honesty

and benevolence.

Although the importance of interpersonal dynamics is

widely recognized in the literature the role played by

emotions in shaping these dynamics has yet to be explicitly

articulated. For example, Gummesson (1996) describes

personal relations as a mega-structure that exists above

and beyond the market but does not elucidate the linkage

between the market and non-market forces in shaping the

relationship. Likewise, Cova and Salle (2000) talk about the

emotional superstructure of a relationship but do not

explicitly delineate the nature of this superstructure. However, one does find a few streams of research that implicitly,

if not explicitly, highlight the role that may be played by

emotions. In an empirical study, Witkowski and Thibodeau

(1999) stress the importance of positive emotions in

establishing and maintaining international buyer supplier

relationships.

Similarly, some other theorists have highlighted the

importance of relationship atmosphere (Hallen & Sandstrom, 1991; Sandstrom, 1992). Relationship atmosphere is

defined by Williamson (1975) as the emotional setting in

which business interaction takes place. Atmosphere consists of the rules (relational norms, emotions and percep-

524

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

tions held) that govern exchange activities. Despite the

relevance and seminal contributions of the relationship

atmosphere concept, the concept as articulated in the

existing literature is not without its shortcomings. As

currently conceptualized the concept of relationship atmosphere addresses six specific atmospheric dimensions: (1)

power/dependence balance; (2) cooperativeness/competitiveness; (3) trust/opportunism; (4) understanding; (5)

closeness/distance; and (6) commitment. First, it is not at

all clear to us that the six dimensions are independent

constructs. There is a need for a better specification of the

constructs themselves as well as of the relationship among

them. Secondly, some of the items included in this

dimension define the context of the interaction rather than

being an inherent aspect of the interaction process per se.

Finally, the different elements constituting the relationship

atmosphere dimension can be viewed as outcomes of

specific interactions rather than capturing how emotions

actually shape relationship development.

3. The concept of emotion

An emotion is a high intensity affective state that is a

product of the actors ability or inability to attain their goals

(e.g., Lazarus, 1991; Oatley, 1992). Actors experience

positive emotions when they are able to attain their desired

goals and they experience negative emotions when they are

unable to achieve their desired goals. The determination

whether a goal has been attained or not is a product of an

appraisal process. Appraisal theorists posit that emotions

reflect the emergence of a discrepancy between an actual

and a desired outcome (e.g., Frijda, 1986; Roseman, 1991).

The appraisal process may or may not be a conscious

process (e.g., Bagozzi, Gopinath, & Nyer, 1999) but it is

fundamental to meaning creation (e.g., Planalp, 1999). As

Planalp (1999: 23) notes Appraisal is not only a matter of

deciding whether an event is good or bad, your fault or

mine, frightening or manageable; it is also the process of

understanding the meaning of events in the broadest and

deepest sense. Emotions vary in their frequency, duration

and intensity (Kumar, 1997). It is also worth noting that

evaluation (good, neutral or bad), potency (strong vs. weak)

and activity (active vs. passive) are also a fundamental

dimension of emotions (Heise, 1987).

The impact of emotions is multifaceted. Emotions shape

behavior (Ben ZeEv, 2001); influence decision-making

(e.g., Carnevale & Isen, 1986; Isen, Shalker, Clark, & Karp,

1978); and condition the negotiating strategies used by

actors (e.g., Greenhalgh & Chapman, 1998). The existence

of a reciprocal linkage between emotions and cognition

with cognitive states giving rise to emotions and

emotions shaping cognitive states is maintained. In this

paper it is argued that emotions influence perceptions of

the other partys behavior. There is a considerable amount

of evidence suggesting that emotions influence the

perceptions of the trustworthiness of the counterpart

(Kumar, 1997). It is also maintained that emotions

determine whether the behavior of the actors is framed

positively or negatively. The term frame refers to how

actors construe of or define the situation (Lewicki, Barry,

Saunders, & Minton, 2003). Scholars have identified a

number of alternative frames that may be used by

individuals in a given situation (Gray, 1997; Gray &

Donnellon, 1989). Of particular relevance in this context

is the loss gain frame. In the paper it is suggested that

positively framed behavior would highlight the potentiality of gain in an interaction whereas a negatively framed

behavior would highlight the potentiality of loss in a

given interaction. If the prospect of gain is more salient

in an interaction people are likely to enact behaviors that

may lead to the successful completion of a transaction

whereas if the prospect of loss is more salient people

may well behave in ways that may undermine the

possibility of a successful completion. It is also claimed

that positive outcomes will tend to reinforce trust while

negative outcomes may undermine them. Relatedly, trust

or lack of trust may also have an impact on subsequent

cognitions. The thrust of the argument is encapsulated in

Fig. 1.

PSYCHOLOGICAL STATES

Cognition

Affect

positively

vs negatively

framed

behavior

perception of

other party's

behavior

Behavioral

Outcomes

Reinforce or lessen

trust

Fig. 1. The causal linkage between affect, behavioral outcomes and trust in business relationships.

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

3.1. Emotions and judgments of trustworthiness

The initiation and the development of trust among

persons involved in exchange activities has been described

as one of the most crucial aspects of relationship marketing.

There is a considerable amount of research documenting the

importance of interpersonal trust (or lack thereof) on buyer

seller relationships. For example, research on marketing

channels has demonstrated the importance of social satisfaction on trust and commitment (Geyskens et al., 1998).

In buyer seller relationships, the trustworthiness of

exchange partners has been defined in terms of motive

and behavior predictability (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). The

process of trust formation is most often seen as a process of

experiential learning in which expectations are developed,

tested and reformulated through critical encounters (Dwyer,

Scurry, & Oh, 1987; Ford, 1980; Wilson & Jantrania, 1995;

Witkowski & Thibodeau, 1999). Trust is widely viewed as a

strategic asset in business relationships. It permits buyers

and sellers to exchange valuable information without the

concern that their partner may exploit them (Ring, 1996). In

other words, trust is intimately related to the desire to take

the leap of faith into a binding business arrangement,

involving high-risk coordination (Dwyer et al., 1987). Trust

formation in business relationships is primarily discussed

from a rationalistic/cognitive viewpoint that has its origins

in the work of social exchange theorists like Blau (1964)

and Emerson (1962). This perspective views trust building

from a rational perspective given the pre-existence of

enablers and insurers of trust (Bradach & Eccles, 1989).

An important enabler is the recognition by the exchange

partners that they can gain more from long-term collaboration than from short-term transactions or defection (Ford,

Hakansson, & Johanson, 1986). A related factor is the cost

associated with alternative governance forms. The ability to

safeguard market transactions via contract is impeded by the

fact that in many instances the buyer seller relationship is

often co-evolving. Ex ante rulings on perceived contract

violations are problematical inasmuch as they necessitate

mutual learning. It is for this reason that firms often stick

with exchange partners with whom they have interacted

previously.

Furthermore, as game theorists have pointed out,

decision-makers limited information-processing capacity

makes global ex ante calculations of others potentially

harmful intentions less efficient than relying on ex post

experience building (Axelrod, 1984). It is also the case that

in business markets there are several retaliatory mechanisms

available for ensuring that defection of trust can be

punished. Social mechanisms such as restricted access,

reputation and collective sanctions provide the conditions

for reliance on trust (Jones, Hesterly, & Borgatti, 1997).

The cognitive perspective notwithstanding, there is a

growing belief that factors other than cognition are

important in initiating and sustaining relationships. Interpersonal interaction is not carried out in an emotional

525

vacuum (Hallen, Johanson, & Seyed-Mohamed, 1991).

Wicks et al. (1999) note, for example, that positive emotions

are a sine qua non in trust building, as they allow the actors

to take the initial leap of faith, expecting that trust will be

honored. The notion that emotions shape perceptions of the

others trustworthiness is consistent with a wide body of

research suggesting that people frequently use their feelings

as an information source for evaluating others trustworthiness (e.g., Forgas, 1992). It has been argued by many that

affect promotes deeper and more stable levels of trust than

those purely associated with rational arguments (McAllister,

1995; Williams, 2001). McAllister (1995) points out that

trust based on emotional states such as care and concern is

deeper than trust based primarily on predictability. A study

of international strategic alliances by Cullen, Johnson, and

Sakano (2000) drew a distinction between credibility trust,

which constitutes the rational component of trust building

and benevolent trust, which constitutes the emotional

dimension.

3.2. Emotions and behavior

A major aspect of emotions is that they have an

immediate and a direct impact on actors behaviors (e.g.,

Ben Zeev, 2000; Frijda, 1986). Different emotions are

associated with different behaviors. For example, the

emotion of fear induces the individuals to withdraw from

the interaction while the emotion of anger induces the

individual to act in a hostile manner against the agent who

has instigated the persons anger. Theorists have also drawn

a distinction between agitation-related vs. dejection-related

emotions (Higgins, 1987). Agitation related emotions in the

nature of tension, anxiety and/or fear impel the individuals

to withdraw from the interaction while dejection related

emotions in the nature of frustration; disappointment and/or

dissatisfaction compel the actors to become much more

aggressive in their behavior. On the other hand, strong and

positive emotions impose a high load on decisions and may

enforce overruling analytical heuristics and jumping to

conclusions, impeding rational decision-making (Gallois,

1994). The recognition that emotions have a direct impact

on behavior has a number of different implications for

understanding the dynamics of the buyer seller relationships. First of all, if negative emotions emerge very early in

a buyer seller relationship and they are not dealt with by

one or all of the parties appropriately the probability of a

successful consummation of a deal is significantly reduced.

If, by contrast, emotions emerge at a later phase parties will

need to exert effort to manage the ensuing conflicts in an

appropriate way. The effective management of emotions at

this phase may strengthen the relationship whereas an

ineffective management of emotions will surely worsen the

relationship and may well lead to premature termination.

Often enough in interpersonal interactions a negative

vicious circle develops. In these cases the negative emotions

experienced by the different parties feed on each other

526

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

potentially leading to conflict escalation (George, Jones, &

Gonzales, 1998; Kumar, 1999). Vicious circles are hard to

contain and may become even more problematical in

relationships that cross national boundaries (Kumar,

2004). Secondly, if a buyer seller relationship experiences

negative emotions frequently crisis management will be the

order of the day. This increases the transaction costs for

managing the relationship and one or all of the other parties

may feel compelled to search for new business partners.

Thirdly, the greater the intensity of the negative emotions

that emerge in interactions between the buyer and the seller

the more problematical it would be to repair the relationship.

Indeed, at a certain critical threshold there may well be no

option but to terminate the relationship.

3.3. The impact of emotions at the individual, the intergroup

and the top management levels

Although emotion is a micro level variable it can

potentially affect behavior not just at the individual level

but also at the group and the top management levels. House,

Rousseau, and Thomas-Hunt (1995) suggest that micro

level variables affect macro level variables when there is a

high level of situational ambiguity and/or when the different

units in an organization are tightly coupled with each other.

Tight coupling means that the actions of the different

organizational entities are highly interrelated with each other

whereas situational ambiguity necessitates the importance of

collective sense making in arriving at a shared definition of

the situation. Actors will be strongly motivated to engage in

collective sense making when the situational ambiguity is

high. It is for this reason that it is useful to assess the impact of

emotions on buyer seller relationships at (a) the individual

level; (b) the intergroup level; and (c) the interorganizational

level. The emotions that emerge at the individual level have a

strong impact on how easily the actors are either able to

initiate a relationship, sustain it, or deepen it should that be a

strategic priority. In other words, emotions have a powerful

impact on the level of cooperative behavior exhibited by

individuals (Jones & George, 1998). Cooperative behavior

may mean, for example, that the actors are willing to

exchange relevant information in a timely way, are inclined

to assist the other party should their be a need of doing so,

are concerned not just about their welfare but also about

the welfare of the other party. Cooperative behavior is

essential in fashioning and sustaining an integrative agreement, i.e. an agreement that is mutually beneficial for all

concerned.

Intergroup interactions are fraught with tension as the

emergence of new relationships leads to re-drawing of group

boundaries, which may affect the individuals identity, and

their social position in the preexisting groups of which they

are currently a member (Gould, Ebers, & Clinchy, 1999). To

begin with people are uncomfortable with a change in their

status, and especially so, if the change may have negative

connotations. Secondly, people possess positive feelings

towards the social groups with which they identify

themselves, whereas they may hold neutral or even negative

feelings toward members of other groups. The negative

feelings towards members of the other group are likely to be

enhanced when the groups see themselves in competition

with each other. The emergence of negative emotions

lessens the possibility of cooperative behavior for the reason

that it decreases the motivation of the group members to

trust others coming from a different group (Williams, 2001).

One would surmise that the greater the cultural distance

between the partner firms, the greater the impact of negative

emotions on cooperative behavior.

The emotional dynamics in buyer seller relationships

get activated not simply at the individual or the intergroup

level but may also get activated at the top management

level. This is particularly likely to be the case when the

buyer seller relationship is a strategic one. It is surmised

that the emergence of emotions at this level has a

phenomenological significance that is qualitatively different

from what occurs at the individual or the intergroup levels

(Kumar, 2002). The emotional dynamics that get instigated

at this level, no matter how rare, are of crucial significance

because the decision-makers at this level can crucially

decide as to whether to continue or discontinue the

relationship. In other words, what happens at this level

has a decisive strategic significance. A good example of this

is the highly emotionally charged conflict that developed

between General Motors and Volkswagen when one of

General Motors employees defected to Volkswagen (Puri,

1997). As Puri (1997: 24) points out It had been an ugly,

very public war, dragging across the courtrooms of two

continents, costing each company millions of dollars, and

even threatening to destabilize German American relations. While the parties had made attempts in the

intervening period to settle the dispute, their attempts to

do so had not been successful. The dispute settlement was

facilitated by third party mediation and its success was

enhanced by the realization among the parties that the costs

of not resolving the dispute were becoming larger by the

day. The nature of the final agreement called for both parties

to exchange what Puri calls intentionally ambiguous

letters, a reduction in the level of trade among the two

parties, a payment of US$100 million dollars by VW to

GM, and the ouster of Lopez from Volkswagen. This was an

intractable conflict, which was not easily settled because it

involved management at the highest levels of the organization and reflected a strong feeling of bitterness and

resentment that had developed among the parties.

4. Emotions and the development of business

relationships: a model and propositions

The business relationship cycle is usually conceptualized

as a discrete process, comprising the stages of initiation,

development, management and termination (Dwyer et al.,

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

1987; Ford, 1980; Frazier, 1983). The nature of interpersonal interaction is different at each of these stages

(Hallen & Johanson, 1990). It is also worth noting that at

each of these stages a number of individuals are involved

each of whom plays a different role (Kumar & Andersen,

2000). Thus, as argued in the earlier part of the paper the

impact of emotions on the evolution of the relations may be

studied either at the individual, the intergroup and/or the top

management level. At an individual level it is important to

differentiate between those involved directly in the interorganizational process (so-called boundary spanners) and

those only indirectly related to it. Likewise at a group level a

distinction between groups of individuals directly affected

by the initiation, management, termination and possible reestablishment of buyer seller relationships and those outside this process can be made. Adding to the complexity of

the analysis is the dynamic nature of the groupings of

individuals and the demarcation of boundaries in relation to

these groups. As buyer seller relationships evolve, individuals develop personal bonds with personnel located in

the exchange partner. Moreover, the successful development

of business relationships is associated with increasing

commitment and mutual adaptation, involving an increasing

number of individuals and departments on both sides of the

buyer seller dyad. Therefore, personnel groupings indirectly involved in the initiation phase of the business

relationship may become directly involved as the relationship commences. Finally, new personnel groupings (i.e.

interorganizational task forces) may be formed during the

relationship development and others (i.e. negotiation teams

established to initiate the relationship processes) may

dissolve.

For the purposes of this paper differentiated positions of

individuals and groups present in the buyer seller relationship formation process have been identified. These roles are

portrayed in Fig. 2.

4.1. Emotions at the individual level

As argued earlier buyer seller relationships have the

potential for generating negative as well as positive emotional reactions among individuals. The intensity of the

emotional reaction among the involved actors depends on a

number of different factors. The greater the unexpectedness

Fig. 2. Organizational groupings and boundary spanners in buyer seller

relationships.

527

and the counternormative behavior of the buyer and/or the

seller the greater the intensity of the emotional reaction in

the other party. It is also important to be cognizant of the

fact that there are individual differences in terms of how

people experience and respond to emotions. A number of

individual difference variables have been identified in the

literature. Positive vs. negative affectivity (Watson & Clark,

1984), emotional intelligence (Salovey & Mayer, 1990), the

need for affect (Maio & Esses, 2001) are some of them. For

example, individuals who score high on positive affectivity

may either not experience negative emotions when unable to

complete their goal or may experience them at a much lower

intensity level. Similarly individuals who are emotionally

intelligent will be able to discern the emotions of the other

party and for that reason act in ways that will facilitate

interaction. Likewise individuals who are high in the need

for emotions are more likely to let their emotions shape their

behavior. Other factors influencing the intensity of the

emotional response are the nature of the prior relationship

between the individuals in the buyer seller organizations,

the complexity of the proposed relationship, and/or the

experience of the individuals in initiating and maintaining

these relationships.

4.2. Emotions at the intergroup level

It has been pointed out earlier that buyer seller relationships also activate distinctive group identities with the

associated implication that the group members have a

positive view of their group members and a negative view

of their outgroup members. Relatedly, it is also important to

note that some individuals and social groups may be closer

to the organizational boundary than others. A key implication of this is that the formation of buyer seller relationships affects social groups differently with the consequence

that the different groups even within an organization may

experience different emotional states. The crucial implication of this is that if an organization is not unified itself how

can it send a consistent message to its partner?

A distinction between two such intraorganizational

groups is drawn, namely (a) organizational members, i.e.

individuals who do not interact with the buyer or supplier

in question, and (b) boundary spanners, i.e. individuals

from the buying and the selling organization who are

directly interacting with each other. Organizational members who play boundary spanner roles are not only

members of a parent organization and subject to expectations and influence attempts of internal members of other

groups but are also members of a boundary interaction

system, which stretches across organizational boundaries.

Marketeers, purchasers and other so-called boundary

spanners act as links between buying and selling

companies. Generally their function is to coordinate work

and ensure a smooth communication between the respective companies. The notion that boundary spanning is an

important function of top management is well demonstra-

528

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

ted in an empirical study by Hallen (1986) who showed

that between 10 and 20 persons typically assumed the role

as boundary spanners on each side of the marketing dyad.

They played multiple roles such as (i) representatives of

their parent organization to the buyer or seller, (ii)

representatives of the buyer/seller to members of their

parent organization and (iii) as negotiators.

The emotional states associated with this role represent

very different interests and for this reason will generate

different emotional reactions within individuals within the

same organization. For example, when the Dutch company Phillips Medical B.V. decided to dismantle parts of

their production activities, reduce staff and develop close

relationships with Danprint, a trusted Danish supplier, this

was perceived very differently among those directly

involved and those indirectly affected. Even though there

was clearly a positive emotional climate among the

engineers from the Danish supplier and the Dutch buyer,

the proposed outsourcing caused fear and anger towards

the Danish supplier among the employees in Phillips

Medical who were affected by the lay-off. Consequently,

they strongly resisted sharing any knowledge with

representatives from this supplier, which harmed the

buyer seller relationship development process considerably (Andersen, 1995). In order to settle this problem and

problems with other suppliers taking over previously in

sourced activities a major reorganization was needed. In

one particular case, employees were offered the possibility

of establishing a company for themselves, and linking to

Phillips Medical as suppliers. This, along with other

actions such as suppliers taking over some of the Phillips

workers, eventually solved the problems faced, and

affected the emotional state of the group, so that more

mixed perceptions and emotional states were present

among the workers at Phillips rather than purely negative.

Likewise, it is reasonable to imagine that a similar process

can occur from the perspective of the seller. For instance,

changing the focus from one key customer to another may

affect resource priorities and the interests of social groups

in a given company, with a similar effect on the

relationship. Although the impact of negative interest

interdependence among different roles has been highlighted it is useful to note that positive interest interdependence may also exist as well. This leads us to

Proposition 1a.

Proposition 1a. The emotional states will be similar if there

is a positive interdependence of interests among them and

will be dissimilar if the interdependence of interests is

negative.

This is not to say that all buyer seller relationships

generate differentiated emotional states within an organization. Very often the consequences of forming relationships

with specific buyers and sellers are less clear ex ante. This

implies that the strength of emotional states may vary,

depending on the specific partnership in question. It is also

the case that in some cases, buyer seller relationships

involve very few individuals or groups within an organization. One implication of this is that while some

individuals may experience emotions of strong intensity

the emotions may not be globally diffused within the

organization. This leads to the following proposition:

Proposition 1b. The intensity of the emotional states among

organizational members and boundary spanners will be

similar if there is positive interdependence among them but

will be dissimilar if there is negative interdependence

among them.

Relationship development is an evolutionary process in

which existing social groups may disband and new groups

may be formed. One consequence of this is that the

emotional dynamics co-evolves with the business relationship cycle. Table 1 highlights the co-evolution of the

emotional cycle with the relationship cycle. The relationship cycle is a developmental cycle entailing the initiation,

development, termination and re-establishment of relationships and it co-evolves with the emotional states among

peer groups and boundary spanners. Consistent with

research on emotion, i.e. Heise (1987) and Heise and

Thomas (1989), the emotional states in terms of the

evaluation potency activity framework are used here,

which, based on cross-cultural research in more than 20

countries, revealed three universal dimensions of emotional

responses. Evaluation concerns the positive, neutral or

negative direction of emotions; potency concerns whether

an emotional state is powerful and dominant or whether it

is powerless. Finally, activation concerns whether an

emotional state appears lively or quiet. For instance, a

positive feeling may be more or less potent (compare

being happy with being overjoyed) and be articulated more

or less subtle.

The centric view, i.e. seeing the development of affective

states across the business relationship cycle from the buyer

or the seller point of view, is not employed. The reason for

this is a belief in the interaction process to be an

interdependent one in which there is mutual interpenetration

of partner by another, albeit in varying degrees.

In the following section the phases of relationship

development are described along with the associated

emotional dynamics and how they typically are expected

to affect trust building in the relationship. Clearly, the

study is partial and a simplified view of a complex

reality, since emotional dynamics outside those created by

the business relationship may affect the development of

trust as well. However, a consistent relationship between

the relationship stages, emotional dynamics stemming

from individuals and groups and trust building is

expected, as outlined in Table 1. The ability to predict

these affective states is based on the notion that emotions

are highly normatively defined. I.e. certain emotional

patterns are culturally reproduced and are supposed to fit

particular circumstance as a consequence of socialization

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

529

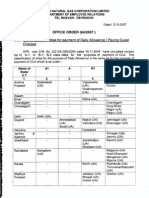

Table 1

A conceptual overview of emotional states among different groupings in relationship development

Boundary

spanner

individuals

Boundary

spanning

group(s)

Peer groups

Implications

for trust

building

Initiation

Development

Voluntary termination

Forced termination

Re-establishment

(following voluntary

termination)

Medium strength,

active,

positive anxiousness

Not established at

this stage

High strength, active,

positive joy

Low strength, active,

negative sadness

High strength, active,

positive anticipation

Medium or low

strength, active,

positive anticipation

High strength,

active, positive joy

Low strength,

passive,

negative fear

Low strength, active,

neutral/positive

anticipation

Medium strength,

active,

neutral confusion

Low strength, active

acceptance

Medium strength,

active, negative

anger

High strength,

active confusion

High strength,

passive, positive

relief

Anxiousness increases

incentives for trust

building by boundary

spanning individuals

but is constrained by

negative emotions such

as fear among peers

resisting change

Trust building

enforced by the

dynamic interplay

of positive emotions

shared and reinforced

among boundary

spanners and boundary

spanner groups

Low strength,

neutral, passive

compliance or

avoidance

Emotional states

following from

re-establishment of

relationship lead to

a gradual rebuilding

of trust

processes. This means that emotional responses can be

patterned to some extent (Heise & Calhan, 1995). Furthermore, the observations are empirically grounded using

illustrative case examples to highlight the usefulness of the

framework.

5. Initiation

At the initiation phase, Dwyer et al. (1987) note that the

actors are engaged in finding the right partner for

collaboration. To this end, the potential partners consider

the obligations, benefits and burdens and the possibility of

exchange. According to Dwyer et al. (1987) the exploratory

relationship is very fragile in the sense that minimal

investment and interdependence guarantee that termination

would not be a problem if circumstances warranted it. In a

similar vein, Heide (1994) notes that relationship initiation

entails an evaluation of potential exchange partners, initial

negotiations about the potential relationship, and some

adaptation if the collaboration goes forward. Ford (1980)

notes that at this stage the partners do not know each other

very well and for this reason there is considerable

uncertainty. While the partners may be aware of the risks

involved, they may have little or no evidence of how to

judge their partners commitment to the relationship.

Although there may be uncertainty in the organization as

to whether or not it is best to proceed with the relationship

this uncertainty may not be universally shared. The

boundary spanners are likely to be positively biased towards

the formation of this relationship for a number of different

reasons. First, the initiation of new relationships provides

new possibilities for boundary spanners in terms of

recognition and achievement. Given that it is their job to

Emotional states

created

from voluntary

termination

have limited effect

on established trust

Negative and

strong emotional

states created

from forced

termination erode

existing trust and

may even create

distrust

initiate these relationships the fact that a relationship has

been established would bring them credit. It is also the case

that while the benefits for the boundary spanners are

immediate the potential costs are not immediately apparent.

It is quite possible that the boundary spanner may have

moved on to another position by the time that it becomes

clear that the relationship is not working.

The rest of the organizational members may not be as

enthusiastic about the relationship. They may either

experience negative emotions or a neutral affective state at

the establishment of new relationships with buyers and/or

sellers. Often, the establishment of a new relationship is

perceived as a possible breach of existing practices, which

may hinder or delay the group members in fulfilling their

existing obligations. This may generate negative emotions

in the form of insecurity and anxiety. A number of empirical

studies have documented the tension that often exists

between the engineering and the marketing group in an

organization. Engineers find that marketers often oversell

the production ability of the organization, whereas marketers find the attitude of engineers hindering their abilities in

accommodating the customers requirements and thereby

winning the tender (Lancaster, 1993).

A good example of how group membership influences

emotional states and trust building is provided in a case

study of Novo, a Danish producer of health care products,

and Nissho, a Japanese supplier of health care products

(Andersen & Christensen, 1999). When engineers from

Novo started negotiations with sales people from Nissho

on the NovoPen their first meetings were enthusiastic, and

promises of strong commitment were evident from both

sides. Shortly thereafter, Nissho representatives declared

that they would provide expertise on the production of

ultra-thin needles, and Novo on the other hand maintained

530

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

that large orders were possible. Even though the NovoPen

represented a radical shift in the technology of diabetes

care, the consumer responses to this new product were

unknown and Novo representatives only provided limited

information on the component to be produced (in order to

protect their innovation). They convinced Nissho sales

representatives about the viability of this product and for

this reason the Novo engineers were invited to meet with

the production engineers from Nissho. However, the

positive atmosphere changed dramatically when the Novo

representatives and the Nissho plant engineers met.

Nissho plant engineers saw the production of this new

type of needles (and the expected volumes) as a potential

threat of loosing face by not being able to live up to

the production and volume performance targets set by

Novo top managers. Therefore, they were eager to

convince the Novo representatives that they were not

able to supply this new product and probably should look

elsewhere for alternative suppliers. However, Novo

managers by showing Nissho managers a specimen from

their existing production were able to convince plant

management that the component they wanted bore a close

resemblance with Nisshos existing component.

The tensions among the boundary spanners and other

organizational members in Nissho and Novo reflect a

mechanism frequently observed in the literature on

industrial sales management. Boundary spanners often

find themselves in a situation of a double-sell, meaning

that they not only must convince prospective buyers and/or

sellers but also must negotiate the deal internally (Organ,

1971). In almost all cases these relations exist in both the

buying and the selling organizations as organizational

members of both buying and selling organizations (apart

from boundary spanners) feel tension, anxiety, irritation

and even hostility. In cross-cultural buyer seller relationships this problem is amplified due to misinterpretations

which may generate or accentuate negative emotions

among organizational members (Cooray & Ratnatunga,

2001; Nair & Stafford, 1998). A further point worth noting

is that while positive emotions undoubtedly lead to

relationship initiation negative emotions may not necessarily lead to relationship termination (Andersen & Christensen, 1999; Cooray & Ratnatunga, 2001; Management

Review, 1997). Negative emotions do not persist forever,

however, strong their intensity level is. This is not to say

that negative emotions do not affect the course of

relationships; the argument is simply that their impact

may be more limited. Based on these observations it is

proposed that:

Proposition 2a. There is a difference in the motivation of

the organizational members and the boundary spanners to

initiate a new buyer seller relationship. This difference is a

product of different emotional states experienced by

members in these groups and it affects their willingness to

engage in trust building behaviors.

Proposition 2b. High intensity negative emotional states

may slow down but not necessarily impair the process of

relationship development in buyer seller dyads.

6. Development

In their seminal piece, Dwyer et al. (1987) note that the

development phase is characterized by an increasing

interdependence among the alliance partners. The development of trust during the initiation of the relationship leads to

increased risk taking among the partners. One consequence

of this is the reduction of uncertainty and lessening of the

psychological distance between the partners.

A good example of this is the relationship between Nissho

and Novo Nordisk. The collaboration between Nissho and

Novo Nordisk deepened during the development and

successful launch of NovoPen\. As pointed out by Sako

and Helper, Japanese subcontractors expect frequent interaction, mutual recognition and support in their relationships

with customers. They prefer not to resolve issues through

contracts and arms length agreements (Sako & Helper,

1998). Novo Nordisk representatives learned from their

initial experience with the Japanese company that matters

must be solved in face-to-face talks. Novo Nordisk sees this

as a part of the Japanese business culture and has learned to

cope with this dimension of doing business in Japan:

You cannot conduct business with the Japanese only using

a telephone, a fax and the Internet. You need to be there and

to know them on a personal basis, and you must try to

develop close personal relation to them. Also they need to

know you on a personal level. (Jrn Rex, Product

Development Manager, Novo Nordisk)

Over the years, both Nissho and Novo Nordisk developed

their ability to collaborate in spite of cultural as well as

physical barriers among them. Four staff members from

Novo Nordisk worked together with 6 10 Nissho staff

members on a regular basis, improving the needle. Novo

Nordisk developed a culture sensitivity seminar for employees who were to encounter their Japanese partners for the

first time. Moreover, a person, who had already developed

personal relations with his/her Japanese colleagues, always

accompanied employees who needed to be introduced to the

Japanese for the first time. On the other hand, the Nissho

organization has also developed its interpersonal skills for

managing trust formation across organizational and cultural

boundaries. First, Nissho employees who were involved

directly with Novo Nordisk improved their English-speaking capabilities considerably. The employees from the

Japanese partner who took part in the exchange activities

with Novo gradually became aware of the Danish business

culture. Therefore, discussions between Danish and Japanese engineers became more open-ended and informal than

previously, indicating the emergence of affect based trust.

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

The emergence of affect-based trust is also well reflected

in how the parties began to interact with each other. For

example, Novo Nordisk involved Nissho at an early stage of

any product modification that may have an impact on the

production of the needles. Moreover, meetings were

frequently held between various functional specialists from

Novo and Nissho. On the other hand, Nissho management

was willing to give Novo Nordisk access to all its

development activities related to the fabrication of needles.

Nissho has opened all their doors for usall of them,

because they have realized after 15 years of collaboration

that we are serious business partners, who keep our

promises and do not conduct industrial espionage.

(Production Engineer, Novo Nordisk)

In the early years of collaboration the development of

close personal relationships as somewhat problematical with

the consequence that interorganizational was impeded. As

an example, individual staff members might make deals and

agreements, which would not be in agreement with the

overall mission of the respective firms, or alternatively, the

decisions may not be communicated to all of the persons

involved. To prevent these problems from occurring Novo

Nordisk developed a procedure whereby all formalized

agreements were to be vetted. At Novo Nordisk there were

two persons who were responsible for this procedure: One

took care of the technical aspects, including alterations of

designs, development projects, etc. while the other was in

charge of the commercial aspects of a relationship.

Simultaneously, a yearly meeting was held at both the top

and middle management levels in order ensure the smooth

functioning of the relationship.

The case outlined above demonstrates the fact that

affective states influence trust building. Trust based on

affect is assumed to create deeper levels of trust, which can

create conditions for closer collaboration that may even

resist trust violations (Williams, 2001). If, on the other

hand, the partners differ in their value systems negative

affect may emerge and their ability to deepen trust will be

compromised. Negative emotions such as anxiety, contempt and disgust decrease the motivation to trust and

prompt more distanced relationships among groups. Such

relationships may be characterized by semi-distrust,

suggesting that social exchange may continue despite the

breach of trust. However, such relationships are monitored

carefully (Witkowski & Thibodeau, 1999). In this situation

trust based on faith may be replaced or reverted to a

calculative trust form, which implies close monitoring. As

pointed out, trust and surveillance are not necessarily each

others opposites, as decision-makers need information in

order to learn (or re-establish) about others trustworthiness

(Tomkins, 2001). Therefore the following proposition is

developed:

Proposition 3a. Positive affective states among boundary

spanners in buyer seller dyads will lead to the development

531

of trust expeditiously and in doing so will lessen the need for

additional information.

Another consequence of affect is the re-drawing of

boundaries around social groups. Positive affective states

may lead to the formation of new social groupings across

organizational boundaries, which may create tensions

among intra-organizational groupings.

Proposition 3b. Provided negative interdependence, the

establishment of trust among boundary spanners in the

buyer seller dyad will undermine trust among organizational members in the buyer and the seller organization.

7. Termination

According to Dwyer et al. (1987) this phase is

characterized by the possibility of withdrawal or disengagement from the relationship. Although the partners can

withdraw from a relationship at any stage, when the

dissolution occurs after the relationship is perceived by

the partners to be exceedingly good, the emotional

consequences of termination are likely to be particularly

severe. When expectations are high any violation of

expectations may have severe consequences, especially so

if the violations are attributed to the other partners

intentionality. Negative emotional states of high intensity

can cause a complete rupture of the relationship. For

example, in the alliance between KLM and Northwest

Airlines, strong negative affective states among top level

management were said to be the cause for the termination of

the alliance. The alliance between KLM and Northwest was

plagued by mutual suspicion and distrust at the outset.

Mutual antipathy and negative sentiments appeared to be

dominant in the relationship. The Dutch felt that Northwest

management were more deal-makers than airline operators and it led KLM management to undertake court action

to wrest control over the venture (Lewis, 1999). The

Americans undertook a counterattack by seeking to prevent

KLM from acquiring control. All of this was occurring at a

time when the alliance was being profitable. Although the

partners have now managed to put their differences aside

and the alliance seems to be functioning well, the venture

appeared to have been nearly undermined by the presence of

negative emotions on either side.

The strong negative affective states are likely to have

generated distrust among the partners leading them to

consider exiting the alliance. A situation of high distrust is

one, which is associated with fear, cynicism, and a high

degree of vigilance (Lewicki, McCallister, & Bies, 1998).

As groups socialize members into holding shared views and

share emotions, groups may magnify and propagate

negative affective states to other organizational members

(Janssen, Vliert, & Veenstra, 1999). The amplification is

likely to be particularly pronounced when these groups are

532

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

influential within the organization. Likewise, the emotional

states of groups, which have little or no influence on the

organization, may only have limited or no effect on

relationship termination. It can therefore be proposed, that:

Proposition 4a. The impact of group level negative

affective states is dependent on the influence exerted by

the group. The greater their influence, the greater the

likelihood that negative affective states will lead to

relationship termination.

In some cases, strong negative interpersonal emotions

held by influential actors toward one or more members of

the exchange partners organization could lead to rapid

dissolution of the relationship. For instance, the lack

personal chemistry among top managers may lead to

negative affective states such as suspicion and distrust. In

turn, a vicious spiral may confirm top managers in their gut

feeling and set a negative personal tone for the further

development of the relationship.

Proposition 4b. Negative affective states held by influential

individuals within the buying and/or the selling organization may make relationship termination more likely.

8. Re-establishment

Although firms may discontinue their relationships, it is

conceivable that they may try to re-establish the relationship

at a later state. Negative emotions may tend to dissipate over

time, making it easier for the individuals to renegotiate the

relationship. The individuals who may have been previously

involved in bitter conflicts may no longer now be working

for one or all of the organizations or may have moved on to

a new position. Even when relationships are terminated,

they are often done with a heavy heart reflecting the

emotional ambivalence that is so predominant in mixed

motive interactions. A residue of positive affect may be

conserved and this may well be the main driver for the reestablishment of relationships (Havila & Wilkinson, 2002).

This is also reflected in the Novo Nissho case. Although in

this specific instance the relationship did not break down

entirely it experienced severe strain and damage control

measures had to be initiated by Novo Nordisk.

At an intermediate stage of the subcontractor relationship

with Nissho, Novo Nordisk invested in a production line-for

needles to the pen. The line was staffed with Nisshos

employees. By making these investments Nissho and Novo

Nordisk had both demonstrated a shared commitment to the

relationship, which was very much in line with the Japanese

tradition of subcontractor relationships.

Because of the merger of Novo and Nordisk Gentofte,

the new Novo Nordisk took over a needle fabrication plant

in Hjrring, Denmark. Partly based on semi-manufactured

needle tubes from Nissho, this plant manufactured needles

for the pen launched by Nordisk Gentofte in 1986. After the

merger Novo Nordisk equipped the plant to produce needles

for NovoPen\ and the NovoLet\ alongside the needles

bought.

The unexpected knowledge that Novo Nordisk had set up

their own production of needles in Denmark caused a

deterioration of the relationship among the partners. They

feared that Novo Nordisk would phase out their production

line at Nissho and eventually transfer the knowledge of

grinding thin needles to their in-house plant. The result was

that Nissho became less committed towards participating in

development activities. In the words of a Novo Nordisk

manager:

They saw the Danish facilities as a direct competitor and

did not want to give anything before Novo Nordisk gave

something to them. (Subsidiary Manager, Novo Nordisk,

Japan)

First, Nissho suggested that their new plant in Taiwan

could function as a secondary source of supply. However,

Novo Nordisk needed to ensure that delivery would

continue even if Nissho went bankrupt. Novo Nordisk

spent a lot of time and effort in convincing Nissho

management that the Danish subsidiary mainly worked as

a secondary supplier to ensure delivery and was by no

means a threat to Nissho. The fact that the Danish plant

only had a fraction of the production capacity needed and

that it had insufficient development capabilities helped to

convince Nissho managers although the process did take

time. All development activities were still to be conducted

with Nissho. Finally, Novo Nordisk is now using longterm delivery contracts in which the purchased amount is

settled up to 5 years ahead. In spite of the emergence of

this conflict, Novo Nordisk and Nissho have remained

business partners. Nissho currently supplies the Novo

Nordisk plant with needle parts and assists them in their

operations.

The ability of Novo Nordisk to establish the relationship

is a clear reflection of the fact that notwithstanding the

emergence of the conflict between the partners there was a

certain level of positive affective bonding among the

partners, which allowed them to continue with the relationship. Affective trust has often been described as deeper and

longer lasting than trust primarily based on cognition

(McAllister, 1995). It is less fragile. The re-establishment

of buyer seller relationships are less governed by formal

interaction norms than the initiation of them for the simple

reason that the parties are bound together by a prior history.

This leads us to the following propositions:

Proposition 5. The re-establishment of business relationships is critically dependent on the emergence of positive

affective states among influential organizational members in

the buyer seller dyad.

In some industries, recurrent project-oriented business

relationships are the norm (Cova & Salle, 2000). Informal

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

interpersonal bonds play a major role in the re-activation

of relationships (Havila & Wilkinson, 2002) and are

therefore the prime drivers for the reestablishment of the

relationships.

533

at multiple organizational levels. This undoubtedly poses

methodological problems but is nevertheless something

that ought to be attempted if a full understanding on how

these relationships evolve over time is to be reached.

Hopefully, researchers will build on this in the years to

come.

9. Conclusions and implications

The purpose of this paper is to develop an integrative

framework for explaining how buyer seller relationships

develop over time. While many theorists have made an

attempt to explain the evolutionary development of these

relationships few, if any, theorists have paid explicit

attention to the role played by emotions in this process.

There are important reasons to address this issue in the

realms of relationship marketing as well. First of all,

emotion as an influential force in shaping relations in

marketing is widely acknowledged among practitioners.

Concepts such as personal chemistry and its role in

shaping business relationships abound in the management

press. The strong interest among marketing practitioners

in these concepts indicates that more systematic knowledge on emotions and their role in shaping buyer seller

relationships is called for. Moreover, the role of emotions

in shaping business relationships is being dealt with in

research disciplines with which the relationship marketing

research community often has much in common. The idea

that emotions play a crucial role in shaping interorganizational interaction is now becoming increasingly influential

(e.g., Gould et al., 1999) and if this is indeed the case

then theorists must seek to articulate the mechanisms and

the consequences of emotional processes for the development of buyer seller relationships. This perspective is

clearly underdeveloped and may help moving the

theoretical perspectives in marketing closer to the world

of the marketer. An attempt has been made in this paper

to sketch out the mechanisms through which emotion

exerts its impact and the possible consequences of

emotional activation on subsequent relationship development, taking departure in the way in which affective

states influence managerial trust building. The framework

outlined in this paper is meant as a starting point for

additional research in this field. Knowledge on this aspect

can be extended in a number of ways. First, while the

importance of understanding emotional dynamics at the

individual and the intergroup levels has been outlined, the

interactive effects between these two levels have not been

specified. That is to say, how do emotional dynamics at

one level affect the emotional dynamics at another level?

Second of all, it may be useful to highlight the contextual

factors that may amplify or dampen the impact of

emotional responses. Although many such possible factors

have been suggested, their possible full impact on trust

building in buyer seller relationships has not been stated.

Finally, understanding the emotional dynamics in buyer

seller relationships calls for longitudinal studies conducted

References

Andersen, P. H. (1995). Strategiske underleverandrsrelationer [Strategic

subcontractor relations]. In F. Valentin, P. Andersen, H. Dalum, & B.

Pedersen (Eds.), Strategiske virksomhedsrelationer [Strategic firm

relations]. Erhvervsministeriet.

Andersen, P. H. (2001). Relationship marketing and communication:

Towards an integrative model. Journal of Business and Industrial

Marketing, 16(3), 167 182.

Andersen, P. H., & Christensen, P. R. (1999). The pen and the needle:

Partner diversity in international subcontractor relationships. Asian

Case Research Journal, 3, 157 168.

Anderson, J. C., & Narus, J. A. (1990). A model of distributor firms and

manufacturer firm working partnerships. Journal of Marketing, 54,

42 58.

Arino, A., dela Torre, J., & Ring, P. S. (2001). Relational quality:

Managing trust in corporate alliances. California Management Review,

44, 109 131.

Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. New York Basic Books.

Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., & Nyer, P. U. (1999). The role of emotions in

marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27, 184 206.

Barry, B., & Oliver, R. L. (1996). Affect in dyadic negotiations: A model

and propositions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 67, 127 143.

Ben Zeev, A. (2000). The subtlety of emotions. Cambridge, MA MIT

Press.

Ben ZeEv, Aron (2001): The subtlety of emotions, psycologuy, 12, 7,

available at www.psycprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00000136/

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York Wiley.

Bradach, J., & Eccles, L. (1989). Markets versus Hierarchies: From ideal

types to plural forms. In R. Scott (Ed.), Annual Review of Sociology, vol.

15 (pp. 97 118). Palo Alto, CA Annual Reviews.

Brierty, E. G., Eckles, R. W., & Reeder, R. R. (1998). Business marketing.

Upper Saddle River, NJ Prentice-Hall.

Bruner, R., & Spekman, R. E. (1998). The dark side of alliances: Lessons

from Volvo-Renault. European Management Journal, 16(2), 136 150.

Carnevale, P. J., & Isen, A. (1986). The influence of positive affect and

visual access on the discovery of integrative solutions in bilateral

negotiations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,

37, 1 13.

Cauley de la Sierra, M. (1995). Managing global alliances: Key steps for

successful collaborations. Wokingham, UK Addison Wesley.

Cooray, S., & Ratnatunga, J. (2001). Buyer supplier relationships: A case

study of a Japanese and western alliance. Long Range Planning, 34,

727 740.

Cova, B., & Salle, R. (2000). Rituals in managing extrabusiness relationships in international project marketing: A conceptual framework.

International Business Review, 9(6), 669 685.

Coviello, N. E., Brodie, R., & Munro, H. (2000). An investigation of

marketing practice by firm size. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5/6),

523 545.

Cullen, J. B., Johnson, J. L., & Sakano, T. (2000). Success through

commitment and trust: The soft side of strategic alliance management.

Journal of World Business, 35(3), 223 240.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (1998). Between trust and control: Developing

confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Academy of Management

Review, 23, 491 512.

534

P.H. Andersen, R. Kumar / Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2006) 522 535

Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer seller

relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51, 11 27.

Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27, 31 41.

Ford, D. (1980). The development of buyer seller relationships in

industrial markets. European Journal of Marketing, 14(5), 339 354.

Ford, D., Hakansson, H., & Johanson, J. (1986). How do companies

interact? Industrial Marketing & Purchasing, 1(1), 26 41.

Forgas, J. P. (1992). On mood an peculiar people: Affect and person

typicality in impression formation. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 62(5), 863 875.

Frazier, G. I. (1983). Interorganizational exchange behavior in marketing

channels: A broadened perspective. Journal of Marketing, 47, 68 78.

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge Cambridge University

Press.

Gallois, C. (1994). Group membership, social rules and power: A social

psychological perspective on emotional communication. Journal of

Pragmatics, 22, 301 324.

George, J. M., Jones, G. R., & Gonzales, J. A. (1998). The role of affect in

cross cultural negotiations. Journal of International Business Studies,

29, 749 783.

Geyskens, I., & Steenkamp, J. -B. E. M. (2000). Economic and social

satisfaction: Measurement and relevance to marketing channel relationships. Journal of Retailing, 76(1), 11 32.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J. -B. E. M., & Kumar, N. (1998). Generalisations

about trust in marketing channel relationships using meta-analysis.

International Journal of Research in Marketing, 223 248.

Gould, L. J., Ebers, R., & Clinchy, R. M. (1999). The systems

psychodynamics of a joint venture: Anxiety, social defenses and

the management of mutual dependence. Human Relations, 52(6),

697 722.

Gray, B. (1997). Framing and reframing of intractable environmental

disputes. In R.J. Lewicki, R. Bies, & B. Sheppard (Eds.), Research

on Negotiation in Organizations, vol. 6 (pp. 63 188). Greenwich, CT

JAI Press.

Gray, B., & Donnellon, A. (1989). An interactive theory of reframing in

negotiations. Unpublished manuscript.

Greenhalgh, L., & Chapman, D. I. (1998). Negotiator relationships:

Construct measurement and demonstration of their impact on the

process and outcomes of negotiation. Group Decision and Negotiation,

7(6), 465 489.

Gummesson, E. (1996). Relationship marketing and imaginary organizations: A synthesis. European Journal of Marketing, 30(2), 31 44.

Hallen, L. (1986). A comparison of strategic marketing approaches. In P. W.

Turnbull, & J. -P. Valla (Eds.), Strategies for International Industrial

Marketing (pp. 235 263). London Croom-Helm.

Hallen, L., & Johanson, J. (Eds.) (1990). Networks of Relationships in

International Industrial Marketing. Greenwich, Connecticut and London: JAI Press Inc., Advances in International Marketing, vol.3 (1989)

xiii xxiii, 3 5, 95 96, 195 197.

Hallen, L., Johanson, J., & Seyed-Mohamed, N. (1991). Interfirm

adaptation in business relationships. Journal of Marketing, 55, 29 37.

Hallen, L., & Sandstrom, M. (1991). Relationship atmosphere in international business. In S. J. Paliwoda (Ed.), New perspectives on international marketing. London Routledge.

Havila, V., & Wilkinson, I. (2002). The Principle of the conservation of

business relationship energy: Or many kinds of new beginnings.

Industrial Marketing Management, 31, 191 203.

Heide, K. (1994, Jan.). Interorganizational governance in marketing

channels. Journal of Marketing, 58, 71 85.

Heise, D. R. (1987). Affect control theory: Concepts and model. Journal of

Mathematical Sociology, 13(1 2), 1 33.

Heise, D. R., & Calhan, C. (1995). Emotion norms in interpersonal events.

Social Psychology Quarterly, 8(4), 223 240.

Heise, D. R., & Thomas, L. (1989). Prediction impressions created by

combinations of emotion and social identity. Social Psychology

Quarterly, 52(2), 141 148.

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect.

Psychological Review, 94, 319 340.

House, R., Rousseau, D. M., & Thomas-Hunt, M. (1995). The meso