Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Cultural Novelty and Adjustment Western Business Expatriates in China - REPLICATION - 2006

Hochgeladen von

johnalis22Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Cultural Novelty and Adjustment Western Business Expatriates in China - REPLICATION - 2006

Hochgeladen von

johnalis22Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Int. J. of Human Re.

wurce Management 17:7 July 2006 1209-1222

O Routledge

Cultural novelty and adjustment: Western

business expatriates in China

Jan Selmer

Abstract Although seldom formally tested, the traditional assumption in the literature

on expatriate management is that the greater the cultural novelty of the host country, the

more difficult it would be for the expatriate to adjust. To be able to test this proposition, a

mail survey was directed towards Western business expatriates in China. Three

sociocuitural adjustment variables were examined: general, interaction and work

adjustment. Although a negative relationship was hypothesized between cultural novelty

and the three adjustment variables, results of the hierarchical multiple regression analysis

showed that there was no significant association between them. Although highly tentative,

the suggestion that it is as difficult for business expatriates to adjust to a very similar

culture as to a very dissimilar culture is fundamental. Implications of this potentially

crucial finding are discussed in detail.

Keywords

Cultural novelty; sociocuitural adjustment; difficulty to adjust; China.

Introduction

There is an intuitive logic to it: what seems very different could be difficult to adjust to

and what appears familiar does not take long to get u.sed to. Although seldom tested by a

rigorous empirical investigation, this has been the default assumption regarding

expatriate adjustment for many years (cf. Black et al., 1991). This seems to be a justified

assumption supported by theory as well as a myriad of anecdotal evidence. Social

learning theory (Bandura, 1977) would predict such an outcome of expatriate

assignments. Perhaps even more convincing, many of us may have felt bewildered when

dumped as tourists in foreign locations unable to speak the local language and feeling

very unsure about what to do next. However, dissenting voices have been heard claiming

that it could be as difficult for business expatriates to adjust to a similar as to a very

different culture (Brewster, 1995; Brewster et al., 1993; O'Grady and Lane, 1996). So,

does it really matter whatever the answer may be? Yes, this is an issue of considerable

theoretical and practical importance. Besides potentially leading to the need to break

new theoretical ground, far-reaching implications can be expected for international firms

with business expatriates if solid evidence can be produced that the traditional

assumption is untenable. This may emphasize the need for international firms to provide

better support for their business expatriates, either through appropriate cross-cultural

Jan Selmer, Department of Management and International Busines.s, Aarhus School of Business,

Fugiesangs Alle 4, DK-8210 Aarhus V, Denmark (tel; -1-45 8948 6828; fax: +45 8948 6125;

e-mail: selmer@asb.dk).

The tnlernalional Journal of tinman Resource Management

ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online 2006 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandf.co.uk/joumals

DOI: 10.1080/09585190600756475

1210

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

training or through more sophisticated selection mechanisms, to ensure that they are well

prepared to deal with assignments in both similar and dissimilar host cultures.

Therefore, the purpose of this investigation is to examine the association between

cultural novelty and expatriate adjustment. This is both relevant and important, since the

adjustment of expatriates may be related to their performance. Although the theoretical

link between expatriate adjustment and performance is conceptually unclear, it has been

observed that expatriate.s who are unable to adjust to work and life at a host location are

also likely to perform poorly (Ones and Viswesvaran, 1997). Emerging rigorous

empirical research supports a positive association between the adjustment of expatriates

and their work performance (Caligiuri, 1997; Kraimer et ai, 2001; Parker and McEvoy,

1993). This is crucial, since the reason for assigning expatriates to foreign locations is to

perform certain work tasks. So, depending on the finding of this study, the cultural

novelty may be a more or less relevant factor in assessing the performance of business

expatriates. Popular notions, such as 'hardship postings' and 'tough assignments',

referring to a radically different cultural context to justify special consideration and

treatment for expatriates, may turn out to be an irrelevant line of argument.

Consequently, the main potential contribution of this investigation is the exploration of

the traditional, intuitively appealing notion ofthe presumed negative association between

cultural novelty and expatriate adjustment.

The place of investigation is China. This host location was selected both for its

growing importance to Western business firms and its dissimilar cultural context

permeating daily life and work of Western expatriates assigned there. The country's

entry into the World Trade Organization has accentuated its importance as a current and

potential market for Western and other international business firms. Virtually

uncontested, China has emerged as the world's most desirable market. With a

population of 1.3 billion, China has one-fifth of the population of the world. In 1979,

when China opened up for foreign investment, foreign businesses started to move in to

claim a share ofthe country's vast markets. China continues to attract more foreign direct

investment than any other developing country. However, establishing operations in

China may constitute more than a financial concern to foreign firms. China is distinctly

different from most other countries. From a Western perspective, China 'is seen as the

most foreign of all foreign places. Its culture, institutions, and people appear completely

baffling - a matter of absolute difference, not of degree.' (Chen, 2001: 17). This makes

China a challenging destination for Western business expatriates, since they have to deal

with a very different way of life than in their own country and they have to perform in an

unfamiliar work context. There is a wealth of evidence suggesting that many Western

business expatriates could find their assignment in China frustrating (Bjorkman and

Schaap, 1994; Kaye and Taylor, 1997; Sergeant and Frenkel, 1998).

After introducing the concept of expatriate adjustment, and especially the

sociocultural aspects of this notion, the association between this construct and cultural

novelty is discussed. Using social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) as the theoretical basis

for this relationship, three hypotheses are proposed. The methodology for testing these

hypotheses is delineated and the results of the analysis are presented. The findings are

discussed in detail, noting potential limitations and implications ofthe study. Finally, the

conclusions from this investigation are drawn.

Selmer: Cultural novelty and adjustment

1211

Expatriate adjustment

Sociocultural adjustment

The concept of sociocultural adjustment has been proposed and defined in the literature

on international adjustment (Searle and Ward, 1990; Ward and Kennedy, 1992; Ward

and Searle, 1991). Sociocultural adjustment relates to the ability to 'fit in' or effectively

interact with members of the host culture (Ward and Kennedy, 1996). Sociocultural

adjustment has been associated with variables that promote and facilitate culture learning

and acquisition of .social skills in the host culture (Cross, 1995; Searle and Ward, 1990).

The sociocultural notion of adjustment is based on cultural learning theory and highlights

social behaviour and practical social skills underlying attitudinal factors (Black and

Mendenhall, 1991; Furnham, 1993; Klineberg, 1982).

Black et al., (1991) argued that the degree of cros.s-cultural adju.stment should be

treated as a multidimensional concept, rather than a unitary phenomenon as was the

previous dominant view (Gullahorn and Gullahorn, 1962; Oberg, I960). In their

proposed model for international adjustment. Black et al., (1991) made a distinction

between three dimensions of in-country adjustment: (I) adjustment to work, (2)

adjustment to interacting with host nationals and (3) adjustment to the general non-work

environment. This theoretical framework of international adjustment covers sociocultural aspects of adjustment and it has been supported by a series of empirical .studies of

US expatriates and their spouses (Black and Gregersen, 1990, 1991a, 1991b, 1991c;

Black and Stephens, 1989). McEvoy and Parker (1995) also found support for the three

dimensions of expatriate adjustment.

Cultural novelty and adjustment

In the literature on expatriate management, the traditional argument is that the greater the

cultural novelty of the host country, the more difficult it would be for the expatriate to

adju.st in the foreign location (Black etai., 1991). This is an intuitively appealing position

supported by common sense and a host of anecdotal evidence. Although conflicting

suggestions have been proposed over the years (Brewster, 1995; Brewster et al., 1993;

O'Grady and Lane, 1996), the tenets of social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) have been

used to justify this initial stance (Black and Mendenhall, 1991).

Theoretical framework

Albert Bandura (1977) is one of the main proponents of social learning theory which

integrates cognitive and behavioral theories. In his book, Bandura (1977) asserts that in

addition to individuals' learning based on the consequences of their own actions,

individuals can also learn and behave based on their vicarious experience, by observing

other people's behaviour and associated consequences and by imitating the modelled

behaviour. In the same source, Bandura further suggests that people are capable of

choosing how they will respond in future situations. The complete theory can be found

elsewhere (Bandura, 1977, 1983) and only theoretical aspects underpinning the

discussion about the association between cultural novelty and expatriate adjustment will

be touched upon here.

Social learning theory would suggest that individuals entering a new culture tend to

pay attention to those elements in the foreign cultural context that are similar to their own

culture and, therefore, seem familiar. They may even superimpose familiarity on

anything that only remotely resembles familiar cues. Given this tendency of selective

perception towards the familiar, individuals are most likely to notice only those

1212

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

differences between their own and the host culture that are clearly visible and striking.

Initially, whether the host culture appears familiar or not, individuals are likely to make

use of past behaviour which in their own culture has proved from successful in similar

situations. However, to the extent that new cultural environment is different from their

own culture, generically similar situations may require radically different behaviours.

Hence, to the extent that the host culture requires different specific behaviours,

individuals are likely to exhibit inappropriate actions. In turn, these inappropriate

behaviours are likely to generate negative consequences (Black and Mendenhall, 1991).

If the cultural novelty of the host culture is large, the frequency of novel situations and

the probability of the newcomers committing behavioural blunders are substantial

(Torbiorn, 1982). There is also a higher probability that the magnitude of the negative

consequences of displaying inappropriate behaviour in a host setting with high cultural

novelty will be greater (Black and Mendenhall, 1991). These arguments based on social

learning theory all seem to suggest that the higher the cultural novelty ofthe host culture,

the more likely expatriates are to exhibit inappropriate behaviours and generate negative

consequences which may adversely affect their adjustment in the foreign location. In

other words, these arguments appear to propose a negative association between cultural

novelty and expatriate adjustment.

Another line of theoretical argumentation can be based on the factors that have been

shown to be important in influencing which models a person selects to focus his or her

attention on. Such factors include attractiveness and similarity of the model (Bandura,

1977). The cultural novelty ofthe host culture is likely to affect the similarity of potential

models and, therefore, the attractiveness of the models (i.e., host country nationals,

HCNs). The greater the dissimilarity between parent country nationals (PCNs) and HCNs

due to cultural novelty, the greater the likelihood that the individual will perceive

the models (HCNs) as less attractive and as a consequence pay less attention to the

behaviours modelled by HCNs. The less attention paid to modelled behaviours, the less

likely the individual is to acquire and retain new behaviours appropriate for the host

culture accurately, and the more likely the individual is to exhibit inappropriate

behaviours (Black and Mendenhall, 1991). The more the individual displays

inappropriate behaviours and experiences negative feedback and consequences, the

greater will be the impediment to adjustment. Furthermore, the greater the cultural

novelty ofthe host culture, the greater the dissimilarity between the individual's notions

of appropriate behaviour and appropriate behaviour in the new culture (Torbiorn, 1982).

The greater the dissimilarity of appropriate and inappropriate behaviours between the

two cultures, the more difficult it will be for the individual to exhibit appropriate

behaviours, even if attention was paid to HCNs as models of appropriate behaviour

(Black and Mendenhall, 1991). Consequently, these arguments also seem to suggest a

negative relationship between cultural novelty and expatriate adjustment. Hypotheses

1 to 3 examine this proposition in terms of the three sociocultural dimensions of incountry expatriate adjustment: general adjustment, interaction adjustment and work

adjustment.

Hypothesis I: Cultural novelty has a negative association with general adju.stment.

Hypothesis 2: Cultural novelty has a negative association with interaction adjustment.

Hypothesis 3: Cultural novelty has a negative association with work adjustment

Selmer: Cultural novelty and adjustment

1213

Method

Sample

A mail survey targeted at business expatriates assigned by Western firms to China was

used as the source to extract data for this study. The number of returned questionnaires

was 165, representing a response rate of 25.2 percent. This is not high, but it is equivalent

or higher than other mail surveys of business expatriates (Harzing, 1997;

Naumann, 1993).

The average age ofthe respondents was 44.68 years (SD = 8.61) and on the average,

they had spent 5.98 years in China (SD = 7.45) and had lived abroad for 9.94 years

(SD = 8.77), including China. Most of the expatriate managers were from the US

(24.2 per cent), Germany (13.3 per cent), Britain (9.7 per cent), Australia (9.2 per cent)

and Denmark (5.5 per cent). Expatriates from other Western countries made up smaller

groups. As shown in Table 1, consistent with other recent studies of business expatriates

(Caligiuri, 2000; Selmer, 2001; Shaffer et al., 1999), most of the respondents were male

and married. Almost all the respondents had managerial positions, of which the majority

was CEOs. Joint ventures were the most frequent place of work. The sampled

respondents were located in most of the 23 provinces of China, but a majority was from

the three largest citie.s: Beijing (32.7 per cent), Shanghai (25.5 per cent) and Guangzhou

(9.7 per cent).

Instrument

Cultural novelty was measured by the scale used by Black and Stephens (1989) adopted

from Torbiorn (1982) (alpha = .77). The expatriates were asked to indicate on a fivepoint Likert-type scale how similar or different a number of conditions were where they

lived in China compared to their home country. As in the original scale, the response

categories varied from I = extremely different to 5 = extremely similar (sample item:

'Everyday customs that must be followed'). For easier interpretation of the results, this

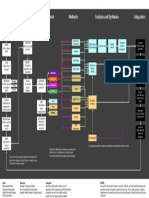

Table 1 Background of the .sample

Background variables

Gender

Male

Female

Married

Position

CEO

Manager

Non-managerial

Type of organization

Joint-venture

Wholly-owned subsidiary

Representative office

Branch

Note: N = 165.

Frequency

157

8

126

95

5

77

125

36

3

76

22

2

68

47

40

6

42

29

25

4

1214

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

scale was reversed in the analysis to make a higher score represent a higher cultural

novelty.

Respondents also completed Black and Stephens' (1989) 14-item scale to assess

sociocultural adjustment. This scale is designed to measure three dimensions: general

adjustment (sample item: 'Food'), interaction adjustment (sample item: 'Speaking with

host nationals') and work adjustment (sample item: 'Supervisory responsibilities'). The

respondents indicated how well adjusted they were to China on a scale ranging from

1 = very unadjusted to 7 = completely adjusted. Principal components factor analysis

with varimax rotation produced the three previously identified dimensions of expatriate

adjustment. Seven items on general adjustment (alpha = .S\) and four items on

interaction adjustment (alpha = .81) were identified. However, due to low reliability,

one of the three items on work adjustment was deleted resulting in a reliability of

alpha = .70 for this two-item factor.

Time in China was used as a control variable. It is essential to control for the time

expatriates had spent in China since expatriate adjustment is a process over time (Black

and Mendenhall, 1991; Church, 1982; Furnham and Bochner, 1986). The variable time in

China was measured by directly asking the respondents how long they had been assigned

to China.

Results

Table 2 displays sample means, standard deviations and zero-order correlations. The

mean score for the variable cultural novelty is significantly higher than the neutral

midpoint, 3.00, of the scale (t = 19.75; p < .001), not surprisingly, suggesting that the

Western expatriates felt that China as a host location represented a relatively high

cultural novelty. Also all of the three variables of expatriate adjustment have

significantly higher mean scores than the midpoint of the scale, general adjustment

(t = 22.35;p < .001), interaction adjustment (t = 17.68;/? < .QQ\) and work adjustment

(r = 34.93; p < .001). This indicates that despite the high cultural novelty, the

expatriates felt relatively well adjusted to the sociocultural context in China.

As presumed, there is a significant positive correlation between time in China and

interaction adjustment (r = .20; p < .05) confirming the need to use time in China as a

control variable. There is also a significant negative association between cultural novelty

and general adjustment ( r = . 1 6 ; p < .05), providing preliminary support for

Hypothesis 2. There was no other significant difference between cultural novelty and

either ofthe other two sociocultural adjustment variables, preliminarily leaving the other

hypotheses unsupported.

The hypotheses were formally tested by means of hierarchical regression analysis.

The control variable, time in China, was entered first. As displayed in Table 3, the control

Table 2 Means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables'

Variables

Mean

1 Cultural novelty

2 General adjustment

3 Interaction adjustment

4 Work adjustment

5 Time in China (control)

3.72

5.51

5.39

5.99

5.98

SD

1.00

1.00

-.16*

-.05

.72

.01

7.45

-.12

.47

.86

1.00

.45***

.46***

.11

1.00

.58***

.20*

1.00

Notes: * p< .05; *** p < .001 (2-tailed)'; 163 < N < 161 due to missing answers.

.07

1.00

Selmer: Cultural tiovelty atid adjustment

1215

Table 3 Results of hierarchical regression for effects of cultural novelty on expatriate adjustmenl

in China"

General adjustment p

Interaction adjustment /3

Work adjustment p

Step I

Time in China

(control)

R

^ (adjusted)

F

Step 2

Cultural novelty

R

Change in /? ^

/f^ (adjusted)

F

.09

.20*

.08

II

.01

1.82

.20

.04

6.69

.07

- .00

.82

-.15

.18

.02

.02

2.06

-.01

.20

.00

.03

3.34

.02

.08

.00

- .00

.45

Notes: " Regression coefficients are .standardized;* /; < .05.

variable was only significant for one of the adjusttnent variables, explaining 4 per cent of

ititeraction adju.stment {beta = .20; p < .05), confirming the preliminary observation

above. The predictor variable, cultural novelty, was entered in Step 2. However, that

failed to produce any significant relationship with any of the dependent variables and,

therefore, no hypothesis was supported.

Discussion

Unexpectedly, the main result of this study is that there was no association between

cultural novelty and any of the three sociocultural adjustment variables: general,

interaction and work adjustment, among the Western business expatriates in China. That

is surprising, although this highly tentative but potentially fundamental finding rnay be

due to a nutnber of limiting circumstances discussed below. Nevertheless, the result

supports the conflicting claims of the nature of the association between cultural novelty

and expatriate adjustment. Although, up to now, generally lacking rigorous empirical

corroboration of these assertions, the argutnent .seems plausible enough. Brewster (1995)

and Brew.ster et al., (1993: 27) have argued that assigning expatriates to a sitnilar culture

can be as much, if not more, of a trying experience as sending them to a very different

culture. For an expatriate assigned to an entirely different host culture, the advantage is

that the consciousness of dissimilarity is always there, whereas tnanagers posted in a

similar culture to their own often fail to identify the differences that do exist and easily

resort to blaming their subordinates or themselves for problems which in reality are due

to the culture clash. In other words, it is the expectations expatriates hold about the new

culture and the attributions they make about what happens in the new culture that will

have a significant impact on expatriates' adjusttnent.

In the light ofthe unforeseen finding of this study it is justified to assess whether it can

be reconciled with the tenets of social learning theory (Bandura, 1977). Since the

consequence of our finding seems to suggest that it is as difficult (or easy) for business

expatriates to adjust to a foreign location with a low cultural novelty as to one with a high

cultural novelty, the discussion will focus on this unexpected trouble of coping with the

familiar. According to social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), there is a tendency for

newcomers to look for or superimpose familiarity on a new cultural context, especially

1216

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

when the cultural novelty seems to be low. Therefore, due to the preference for the

familiar, reinforced by the expectancy of cultural similarity, some cultural mistakes, no

matter how insignificant, will no doubt be committed. In other words, the expatriate

manager assigned to a location with a low cultural novelty does not detect any cultural

differences as he or she is not looking for them since they are not expected. Hence,

ensuing problems that occur may not even be appropriately attributed to cultuial

differences but to other circumstances, such as doubts about one's own leadership

abilities or subordinates' 'laziness' or 'stupidity' (Selmer and Shui, 1999). The outcome

may even be worse than in a case with a high cultural novelty. Expatriates in locations

characterized by low cultural novelty may experience difficulties when trying to deal

with their incorrectly identified problems and they could become increasingly frustrated,

feeling unexpectedly badly adjusted.

Furthermore, this partiality for the familiar is of course not exclusive to the

expatriates, since the HCNs would also be affected by the same mechanism. An

individual, conspicuously from a very different culture, may be tolerated and given the

benefit of a doubt going through the process of trying to adjust to a new culture. On

the other hand, an expatriate from a similar, or presumed identical culture, could be

treated with less patience and given less latitude for culturally deviant behaviour. For

example. Hung (1994) has argued that in China, a Hong Kong Chinese may be judged by

different standards and more harshly than a Westerner for any mistake made because he

or she is presumably knowledgeable about Chinese etiquette and manners and would be

expected to fully understand the appropriate social protocol and behave accordingly.

Expatriates, overlooking any possible cultural differences that may exist in foreign

locations with a similar culture, exhibiting even minor inappropriate behaviours, will

most probably be unfavourably assessed. Their behaviour may even be misattributed and

interpreted by host nationals as evidence of incompetence or that the expatriate is

otherwise unsuitable for the occupied position or the foreign assignment.

Imitating modelled behaviour according to social learning theory (Bandura, 1977)

may not be a priority in a foreign location with a low cultural novelty, since no

modification of behaviour is expected to be necessary. Minor differences in behaviour

are seldom noted and the expatriate may not accurately acquire and retain new variants of

behaviour, making the expatriate continue to exhibit inappropriate behaviours, no matter

how insignificant. Although only mildly deviant, persisting in less appropriate

behaviours may over time become frustrating for the HCNs exposed to the behaviour

of the expatriates. As argued above, this in turn could lead to negative feedback and

consequences for the expatriates reinforcing their frustration and obstruct their

adjustment.

There are also various empirical observations that can be taken as support for the

findings of this study. Through a number of accidental and anecdotal observations,

although obtained by studies with no intentions to formally test the relationship between

cultural novelty and expatriate adjustment, some empirical support can nevertheless be

construed for the finding of this investigation. In a study of the poor performance of

Canadian retailers in the tJS, O'Grady and Lane (1996) concluded that much of the

difficulties seemed to be created by common, but unexplored, assumptions or underlying

beliefs among decision-makers in the Canadian retail companies that these two cultures

are similar and familiar. Although the ability to see differences is necessary for learning

to occur, the Canadian decision-makers were not prepared to look for differences. The

Canadian managers believed that 'Americans were just like Canadians, sharing a similar

language, culture, values, tastes, and business practices. Notably, it was precisely the fact

Selmer: Cultural novelty atid adjusttnent

1217

that these two countries probably are more similar than any other two that masked some

fundamental differences in values and attitudes.'

Based on in-depth interviews of ethnic Hong Kong Chinese business managers

assigned to Beijing and Shanghai, Selmer and Shiu (1999) found that the perceived

cultural closeness seemed to build up expectations of easy and quick adjustment, which

could, if it was not accotnplished, result in frustration, resentment and withdrawal. It was

remarkable how closely the predicament of many ofthe Hong Kong managers resembled

the worst experiences of expatriate managers in general as reported in the literature.

At work, they generally refrained from adapting their managerial style to local

expectations. Instead, they insisted, often in vain, that subordinates adopted parentcountry standards and behaviours, typically resulting in frustration and feelings of

detachment on the part ofthe expatriate manager. Outside work, they avoided socializing

with host nationals, and instead lived in the vicinity of, and sought the company and

social interaction with, other parent-country nationals. Similar predicaments have been

found facing other overseas Chinese managers in China, as for exatnple Taiwane.se

managers in Guangdong Province, ethnic Chinese Singaporean expatriates in Zheijiang

Province, or Malaysian Chinese in Wuxi (McEllister, 1998). Furthermore, comparing the

adjustment of Western and overseas Chinese business expatriates in China, Selmer

(2002b) found that although the Westerners perceived a higher degree of cultural novelty

than the overseas Chinese, they were better adjusted in sociocultural tenns, especially

with regard to work adjustment.

Reporting a study of 36 UK-based companies, Forster (1997) found that respondents

from similar cultures (e.g., USA) were as likely to report adjustment problems as

expatriates assigned to more dissimilar cultures like China. He concluded that the degree

of cultural 'strangeness' of the country does not seem to have any correlation with the

outcotne of the international assignment. Similarly, Peterson et al., (1996) stated that

Japanese MNCs reported that their expatriates appeared to adjust 'about the same' in

different countries, regardless of their degree of cultural similarity to Japan.

Limitations

As usual, this study may have some potential shortcomings that should be considered

when interpreting its findings. As the data were collected through a self-report

questionnaire, single method variance could have affected the results. Therefore, the data

were asses.sed for the presence of single method variance bias. The social desirability

aspect of single method bias often leads to compressed response range (Podsakoff and

Organ, 1986), but an inspection of the data did not reveal any compression of response

range. The data were also directly tested for single method variance bias by applying

Harman's single factor test, one ofthe most common te.sts available for examining monomethod bias (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). All items are hypothesized to load on a single

factor representing the common method. The results ofthe factor analysis identifying the

three sociocultural variables of expatriate adjustment, general, interaction and work

adjustment, suggested that mono-method bias was not a serious concern in this study.

Furthermore, adjustment is a process over time but the method employed here only used

measures of the average level of adjustment at a certain point in time. A longitudinal

approach may have generated a richer data source where different patterns of adjustment

over time could have been identified and compared. On the other hand, longitudinal studies

have other inherent serious methodological challenges (cf. Menard, 1991).

Additionally, the choice of host country for this study could constitute another

potential limitation. As reflected in the high mean score ofthe cultural novelty variable.

1218

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

the Western expatriates generally felt that China had a very dissimilar culture compared

to their own countries. This could have constrained the variance of this variable

contributing to the non-significant relationship found between cultural novelty and the

three sociocultural variables of expatriate adjustment.

Last, but not least, a word of caution. A host of potential flaws and oversights in

designing and carrying out this study could have contributed to the non-significant

results. Despite the careful planning and execution of this investigation, everything from

the non-random selection of target respondents and their relatively low response rate to

potential data processing and errors in the analysis could have biased the results.

Implications

The suggestion based on the highly tentative main finding, that it is as difficult for

business expatriates to adjust to a foreign location when the cultural novelty is low as

when it is high, is fundamental and may give rise to a number of implications, both for

theory, practice and future research. The appropriateness of social learning theory

for justifying the traditional proposition that the greater the cultural novelty, the more

difficult it would be for an expatriate to adjust in a foreign location may be cast in doubt.

In fact, social learning theory can also be applied to explain the conflicting finding of this

study as discussed above. This calls for new theoretical grounds to be broken to further

explore the theoretical relationship between cultural novelty and expatriate adjustment.

The results suggest that business firms assigning expatriates abroad could expect

adjustment difficulties to a similar degree regardless of the extent of cultural novelty.

Therefore, a practical implication for international business firms from this result is that

cultural preparation and training could be useful not only when assigning expatriate

managers to foreign locations with a high cultural novelty, but also for assignments to

host countries representing a low cultural novelty. In other words, wherever business

expatriates are assigned, they may benefit from cross-cultural training. This may be an

important revelation since many business firms do not provide systematic training

programmes for expatriate managers (Dunbar and Katcher, 1990; Mendenhall et al.,

1987; Tung, 1988). Companies seem to be ambivalent on the usefulness of training,

apparently assuming that 'good persons always manage', preferring a learning-by-doing

approach (Black and Mendenhall, 1990; Brewster, 1995; Kuhlmann, 2001). The result of

this study seems to indicate that this may not be such a useful assumption.

However, it is likely that the training should be different for expatriates assigned to

locations with low as opposed to high cultural novelty. Whereas the latter type of

preparation often includes substantial elements of cognitive training, emphasizing

factual information about the host country (Gudykunst et al., 1996), the former would

probably rather focus on creating motivation for the individuals to fine-tune their current

sociocultural behaviour. Directing this change, the intercultural training could focus on

attracting the attention to the most essential nuances of cultural differences and their

behavioural implications in the similar host culture.

Obviously, an alternative way to go about this is to amend the expatriate selection

strategy. Individuals with a good track record of adjustment and performance in previous

foreign assignments could be targeted. They could be better suited to deal with a certain

foreign location, regardless whether it represents a high or a low cultural novelty.

Unfortunately, cross-cultural skills are traditionally not highly valued when selecting

expatriates (Franke and Nicholson, 2002). Of course, especially candidates with

past expatriate experience from the country in question may have acquired skills which

could facilitate their adjustment (Selmer, 2002a). In fact, a previous recent assignment to

Selmer: Cultural ttovelty and adjustmetit

1219

the same host location can be seen as the ideal expatriate training experience, especially

if the assignment was relatively successful. Selecting such candidates, with recent

positive experiences of the host country and work task at hand, could be regarded as a

perfect substitute for cross-cultural training. Another worthwhile endeavour might be to

try to match the personal characteristics of expatriate candidates with the cultural profile

of the host country (Nicholson et al., 1990).

There are several implications for future research involving improving weak points of

the study as well as extending the scope of investigation. Future studies tnay avoid

potential mono-method bias by tapping more data sources in addition to the expatriates,

such as spouses or other family members, colleagues and bosses. A longitudinal

approach can be applied and another host country can be selected that to a lesser extent

may restrict the variance of the cultural novelty variable. In doing so, an extension to

.several host countries could be considered in an attempt to safeguard a sufficient variance

of the independent variable. That would also provide an opportunity to explore the

expression of 'culture toughness' describing a transfer to a certain culture as especially

difficult (Black et al., 1992: 128). Could it be the case that, regardless of the degree of

cultural similarity, transfers from certain cultures to other specific cultures are typically

painful? Future research could extend the current investigation to address this question

and similar issues by carefully selecting more than one host country. One such issue is

the directionality of adjustment problems. For example, is it easier for business

expatriates from China to adjust to the US than it is for US expatriates to adjust to China?

Conctusions

The main finding of this study must be regarded as highly tentative. As this finding is

based on a set of non-significant results, it is acknowledged that a host of potential flaws

and oversights in designing and carrying out this study could have contributed to the

outcome of this investigation. Nevertheless, the suggestion that it is as difficult for

business expatriates to adjust when the cultural novelty is low as when it is high, is

fundamental. Despite its counterintuitive impression, this suggestion is consistent with

both theory and previous empirical observations, although of an anecdotal nature.

Therefore, the finding of this investigation could make an important contribution to the

literature as the first rigorous empirical corroboration of this proposition. The possible

implications may be wide and far reaching for both theory and the practice of managing

expatriates. New theoretical grounds should be broken to explore the relationship

between cultural novelty and expatriate adjustment. The finding also conveys a powerful

message about the need to support business expatriates better, either through appropriate

cross-cultural training or through more sophisticated selection mechanisms to ensure that

business expatriates are well prepared to adjust to host locations with both high and low

cultural novelty.

References

Bandura, A. (1977) Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1983) The Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Bjorkman, I. and Schaap, A. (1994) 'Outsiders in the Middle Kingdom: Expatriate Managers in

Chinese-Western Joint Ventures', European Management Journal, 12(2): 147-53.

1220

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1990) 'Expectations, Satisfaction and tntentions to Leave of

American Managers in Japan', International Joumal of Intercultural Relations, 14(4):

485-506.

Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1991a) 'Antecedents to Cross-Cultural Adjustment for Expatriates

in Pacific Rim Assignments', Human Relations, 44(5): 497-515.

Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1991b) 'The Other Half of the Picture: Antecedents of Spouse

Cultural Adjustment', Journal of International Business Studies, 22(3): 461-77.

Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1991c) 'The Other Half of the Picture: Antecedents of

Spouse Cross-Cultural Adjustment', Journal of International Business Studies, 22(4): 671 - 9 4 .

Black, J.S. and Mendenhall, M. (1990) 'Cross-Cultural Training Effectiveness: A Review and

Theoretical Framework for Future Research', Academy of Management Review, 15(1): 113-36.

Black, J.S. and Mendenhall, M. (1991) 'The U-Curve Adjustment Hypothesis Revisited: A Review

and Theoretical Framework', Journal of International Business Studies, 22(2): 225-47.

Black, J.S. and Stephens, G.K. (1989) 'The Influence of the Spouse on American Expatriate

Adjustment in Overseas Assignments', Journal of Management, 15: 529-44.

Black, J.S., Gregersen, H.B. and Mendenhall, M.F. (1992) Global Assignments: Successfully

Expatriating and Repatriating Intemationai Managers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Black, J.S., Mendenhall, M. and Oddou, G. (1991) 'Toward a Comprehensive Model of

Intemationai Adjustment: An Integration of Multiple Theoretical Perspectives', Academy

of Management Review, 16(2): 291317.

Brewster, C. (1995) 'Effective Expatriate Training'. In Selmer, J. (ed.) Expatriate Matxagement:

New Ideas for International Business. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Brewster, C , Lundmark, A. and Holden, L. (1993) A Different Tack: An Analysis of British and

Swedish Management Styles. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Caligiuri, P.M. (1997) 'Assessing Expatriate Success: Beyond Just "Being There'". In Sunders,

D.M. and Aycan, Z. (eds) New Approaches to Employee Management. Greenwich, CT: JAI

Press.

Caligiuri, P.M. (2000) 'Selecting Expatriates for Personality Characteristics: A Moderating Effect

of Personality on the Relationship between Host National Contact and Cross-Cultural

Adjustment', Management International Review, 40(1): 61-80.

Chen, M.-J. (2001) Inside Chinese Business: A Guide for Managers Worldwide. Boston,

MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Church, A. (1982) 'Sojoumer Adjustment', Psychological Bulletin, 91(3): 540-77.

Cross, S. (1995) 'Self Construals, Coping, and Stress in Cross-Cultural Adaptation', Journal of

Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26: 673-97.

Dunbar, E. and Katcher, A. (1990) 'Preparing Managers for Foreign Assignments', Training and

Development Journal, September: 457.

Forster, N. (1997) 'The Persistent Myth of High Expatriate Failure Rates: A Reappraisal',

Intemationai Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(4): 4 1 4 - 3 3 .

Franke, J. and Nicholson, N. (2002) 'Who Shall We Send? Cultural and Other Influences on the

Rating of Selection Criteria for Expatriate Assignments', International Journal of Cross

Cultural Management, 29(1): 21-36.

Furnham, A. (1988) 'The Adjustment of Sojourners'. In Kim, Y.Y. and Gudykunst, W.B. (eds)

Cross-Cultural Adaptation: Current Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Furnham, A. (1993) 'Communicating in Foreign Lands: The Cause, Consequences and Cures of

Culture Shock', Language, Culture and Curriculum, 6(1): 91-109.

Fumham, A. and Bochner, S. (1986) Culture Shock: Psychological Reactions to Unfamiliar

Environments. London: Methuen.

Gudykunst, W.B., Guzley, R.M. and Hammer, M.R. (1996) 'Designing Intercultural Training'.

In Landis, D. and Bahgat, R.S. (eds) Handbook of Intercultural Training. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Gullahorn, J.E. and Gullahorn, J.R. (1962) 'An Extension of the U-Curve Hypothesis', Joumal of

Social Issues, 3: 33-47.

Selmer: Cultural novelty and adjusttnent

1221

Harzing, A.W.K. (1997) 'Response Rates in Intemationai Mail Surveys: Results of a 22-Country

Study', Intemationai Business Review, 6(6): 641-65.

Naumann, E. (1993) 'Organizational Predictors of Expatriate Job Satisfaction', Journal of

International Business Studies, 24(1): 61-80.

Hung, C.L. (1994) 'Business Mindsets and Styles ofthe Chinese in the People's Republic of China,

Hong Kong, and Taiwan', The International Executive, 36(2): 203-21.

Kaye, M. and Taylor, W.G.K. (1997) 'Expatriate Culture Shock in China: A Study in the Beijing

Hotel Industry', Journal of Managerial Psychology, 12(8): 496-510.

Klineberg, O. (1982) 'Contact between Ethnic Groups: A Historical Perspective of Some Aspects

of Theory and Research'. In Bochner, S. (ed.) Cultures in Contact: Studies in Cro.i.t-Cultural

Interaction. Oxford: Pergamon.

Kraimer, M.L., Wayne, S.J. and Jaworski, R.A. (2001) 'Sources of Support and Expatriate

Performance: The Mediating Role of Expatriate Adjustment', Personnel Psychology, 54:

71-99.

Kuhlmann, T.M. (2001) 'The German Approach to Developing Global Leaders Via Expatriation'.

In Mendenhall, M.E., Kuhlmann, T.M. and Stahl, G.K. (eds) Developing Global Leaders:

Policies, Processes, and Innovations. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

McEllister, R. (1998) 'Recruitment and Retention of Managerial Staff in China'. In Selmer, J. (ed.)

International Management in China: Cross-Ctdturat Aspects. London: Routledge.

McEvoy, G.M. and Parker, B. (1995) 'Expatriate Adjustment: Causes and Consequences'.

In Selmer, J. (ed.) Expatriate Management: New Ideas for International Btt.siness. Westport,

CT: Quorum Books.

Menard, S. (1991) Longittidinal Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mendenhall, M., Dunbar, E. and Oddou, G. (1987) 'Expatriate Selection, Training and CareerPathing: A Review and Critique', Human Re.source Management, 26(3): 331-45.

Naumann, E. (1993) 'Organizational Predictors of Expatriate Job Satisfaction', Journal of

International Business Studies, 24(1): 61-80.

Nicholson, J.D., Stepina, L.P. and Hochwater, W. (1990) 'Psychological Aspects of Expatriate

Effectiveness', Research in Personnel and Human Re.sources Management, Supplement

2: 127-45.

Oberg, K. (1960) 'Culture Shock: Adjustment to New Cultural Environments', Practical

Anthropologist, 7: 177-82.

O'Grady, S. and Lane, H.W. (1996) 'The Psychic Distance Paradox', Joumal of Intemationai

Business Studies, 27(2): 309-33.

Ones, D.S. and Viswesvaran, C. (1997) 'Personality Determinants in the Prediction of Aspects of

Expatriate Job Success'. In Aycan, Z. (ed.) Expatriate Management: Theory and Research.

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Parker, B. and McEvoy, G.M. (1993) 'Initial Examination of a Model of Intercultural Adjustment',

International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17: 35579.

Peterson, R.D., Sargent, J., Napier, N. and Shim, W.S. (1996) 'Corporate Expatriate HRM Policies,

Internationalization, and Performance in the World's Largest MNCs', Management

International Review, 36(3): 215-30.

Podsakoff, P.M. and Organ, D.W. (1986) 'Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and

Prospects', Journal of Management, 12: 531-44.

Searle, W. and Ward, C. (1990) 'The Prediction of Psychological and Soeio-Cultural Adjustment

during Cross-Cultural Transitions', International Journal of Intercultural

Relations,

14: 449-64.

Selmer, J. (2001) 'Psychological Barriers to Adjustment and How They Affect Coping Strategies:

Western Business Expatriates in China', International Joumal of Human Resource

Management, 12(2): 151-65.

Selmer, J. (2002a) 'Practice Makes Perfect? International Experience and Expatriate Adjustment',

Management International Review, 42(1): 71-87.

Selmer, J. (2002b) 'The Chinese Connection? Adjustment of Western vs. Over.seas Chinese

Expatriate Managers in China', Joumal of Business Research, 55(1): 41-50.

1222

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Selmer, J. and Shiu, L.S.C. (1999) 'Coming Home? Adjustment of Hong Kong Chinese Expatriate

Business Managers Assigned to the People's Republic of China', Intemationai Journal of

Intercultural Relations, 23(3): 447-63.

Sergeant, A. and Frenkel, S. (1998) 'Managing People in China: Perceptions of Expatriate

Managers', Joumal of World Business, 33(1): 17-34.

Shaffer, M.A., Harrison, D.A. and Gilley, K.M. (1999) 'Dimensions, Determinants, and

Differences in the Expatriate Adjustment Process', Journal of International Business Studies,

30(3): 557-81.

Torbiom, I. (1982) Living Abroad: Personal Adjustment and Personnel Policy in the Over.seas

Setting. New York: Wiley.

Tung, R.L. (1988) The New Expatriates. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Ward, C. and Kennedy, A. (1992) 'Locus of Control, Mood Disturbance and Social Difficulty

during Cross-Cultural Transitions', Intemationai Journal of Intercultural Relations,

16: 175-94.

Ward, C. and Kennedy, A. (1996) 'Crossing Cultures: The Relationship between Psychological and

Socio-Cultural Dimensions of Cross-Cultural Adjustment'. In Pandey, J., Sinha, D. and

Bhawuk, D.P.S. (eds) Asian Contributions to Cross-Cultural Psychology. New Delhi: Sage.

Ward, C. and Searle, W. (1991) 'The Impact of Value Discrepancies and Cultural Identity on

Psychological and Socio-Cultural Adjustment of Sojoumers', Intemationai Journal of

Intercultural Relations, 15: 209-25.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Alternatives To Difference Scores - Polynomial Regression and Response Surface MethodologyDokument130 SeitenAlternatives To Difference Scores - Polynomial Regression and Response Surface Methodologyjohnalis22Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Writing - Genres in Academic WritingDokument85 SeitenWriting - Genres in Academic Writingjohnalis22100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- ID40Dokument27 SeitenID40johnalis22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Organizational Hierarchy Adaptation and Information Technology - 2002Dokument30 SeitenOrganizational Hierarchy Adaptation and Information Technology - 2002johnalis22Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- How Organizational Climate and Structure Affect Knowledge Management-The Social Interaction Perspective - MEDIATING - variABLEDokument15 SeitenHow Organizational Climate and Structure Affect Knowledge Management-The Social Interaction Perspective - MEDIATING - variABLEjohnalis22Noch keine Bewertungen

- TQM Practice in Maquiladora - Antecedents of Employee Satisfaction and Loyalty - 2006Dokument22 SeitenTQM Practice in Maquiladora - Antecedents of Employee Satisfaction and Loyalty - 2006johnalis22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Work Practices - Employee Performance Engagement - as.MEDIATOR Karatepe 2013Dokument9 SeitenWork Practices - Employee Performance Engagement - as.MEDIATOR Karatepe 2013johnalis22Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- P.strgy - Perform EXCEL - Reliability.validty 2008Dokument18 SeitenP.strgy - Perform EXCEL - Reliability.validty 2008johnalis22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Behavioral Attributes and Performance in ISAs - Review and Future Directions - IMR - 2006Dokument25 SeitenBehavioral Attributes and Performance in ISAs - Review and Future Directions - IMR - 2006johnalis22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A New Generation of Offshore Structures: F.P. BrennanDokument7 SeitenA New Generation of Offshore Structures: F.P. Brennananon_63078950Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- NDT Ultrasonic Phased Array Examination (NDT Examen de Ultrasonido Arreglo de Fases)Dokument2 SeitenNDT Ultrasonic Phased Array Examination (NDT Examen de Ultrasonido Arreglo de Fases)reyserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mobile Shopping Apps Adoption and Perceived Risks A Cross-Country Perspective Utilizing The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of TechnologyDokument20 SeitenMobile Shopping Apps Adoption and Perceived Risks A Cross-Country Perspective Utilizing The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of TechnologyAthul c SunnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Personality Traits in Relation To Academic PerformDokument11 SeitenPersonality Traits in Relation To Academic PerformSittie Aisah AmpatuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Time: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 100 Note: Attempt Questions From Each Section As Per Instructions Given BelowDokument2 SeitenTime: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 100 Note: Attempt Questions From Each Section As Per Instructions Given BelownitikanehiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Descriptive Use Charts Graphs Tables and Numerical MeasuresDokument11 SeitenDescriptive Use Charts Graphs Tables and Numerical Measuresaoi03Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Dessetation PPT ManishaDokument23 SeitenDessetation PPT Manishayogesh sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Contribution of Land Records Management Towards Adherence of Administrative and Governance Challenges in Land SectorDokument62 SeitenContribution of Land Records Management Towards Adherence of Administrative and Governance Challenges in Land SectorYustho MullyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- ROC Curves - A Tutorial (Brown and Davis)Dokument15 SeitenROC Curves - A Tutorial (Brown and Davis)datamuleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Behaviour Research and Therapy: J. Johnson, P.A. Gooding, A.M. Wood, N. TarrierDokument8 SeitenBehaviour Research and Therapy: J. Johnson, P.A. Gooding, A.M. Wood, N. TarrierEmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Akij Comapny Profile ReportDokument99 SeitenAkij Comapny Profile Reportnajeeb ullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- MULE Design Research Process Model v2Dokument1 SeiteMULE Design Research Process Model v2Nur Ahmad FurlongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide To Monitoring and Evaluation Capacity-Building InterventionsDokument110 SeitenGuide To Monitoring and Evaluation Capacity-Building Interventionsijaz ahmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 - The Tourism Planning ProcessDokument20 Seiten2 - The Tourism Planning ProcessAngelhee A PlacidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iso 9001 Interpretation (En) Part.4Dokument6 SeitenIso 9001 Interpretation (En) Part.4jduràn_56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cpu College: Prepared by Name Id No Bekalusnamaw - Mba/202/12Dokument23 SeitenCpu College: Prepared by Name Id No Bekalusnamaw - Mba/202/12biresaw birhanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sit and Reach TestDokument8 SeitenSit and Reach TestrimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sumit Kataruka Class: Bcom 3 Yr Room No. 24 Roll No. 611 Guide: Prof. Vijay Anand SahDokument20 SeitenSumit Kataruka Class: Bcom 3 Yr Room No. 24 Roll No. 611 Guide: Prof. Vijay Anand SahCricket KheloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q4W2 - How To Organize Data SetDokument31 SeitenQ4W2 - How To Organize Data SetJENELYN PENALESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zetica Understanding The Limits of Detectability of UXODokument10 SeitenZetica Understanding The Limits of Detectability of UXORymondNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Tariq IjazDokument18 SeitenTariq IjazJasa Tugas SMBRGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Feedback ProcedureDokument4 SeitenCustomer Feedback Procedureomdkhaleel100% (4)

- Small Porch SwingDokument26 SeitenSmall Porch SwingEngr Saad Bin SarfrazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Explorative Study To Assess The Knowledge & Attitude Towards NABH Accreditation Among The Staff Nurses Working in Bombay Hospital, Indore. India.Dokument2 SeitenExplorative Study To Assess The Knowledge & Attitude Towards NABH Accreditation Among The Staff Nurses Working in Bombay Hospital, Indore. India.International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 Presentation and Interpretation of DataDokument10 SeitenChapter 4 Presentation and Interpretation of DataAnya EvangelistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Measure Digital CXDokument20 SeitenHow To Measure Digital CXMonique MaritzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ogilvy's 360 Digital Influence's Conversation Impact Model For Social Media MeasurementDokument8 SeitenOgilvy's 360 Digital Influence's Conversation Impact Model For Social Media MeasurementirfankamalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conceptual Framework of Right To Information-SEMINAR..ANWARDokument42 SeitenConceptual Framework of Right To Information-SEMINAR..ANWARShabnamNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction of Honda Activa In: ChennaiDokument65 SeitenA Study On Customer Satisfaction of Honda Activa In: ChennaiSampath Bengalooru HudugaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Competence and Productivity Among School Heads and Teachers: Basis For District Research Capacity BuildingDokument6 SeitenResearch Competence and Productivity Among School Heads and Teachers: Basis For District Research Capacity BuildingPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)