Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Dna Dollars Biotechnology

Hochgeladen von

LALUKISCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Dna Dollars Biotechnology

Hochgeladen von

LALUKISCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS

BIOT ECHNO LO GY

DNA dollars

Linnaea Ostroff examines a history of Genentech, the

US company that first made biology a business.

s the mysteries and mechanics of

DNA were being revealed, it was

unclear whether the molecule would

be used for good or evil. Debates raged:

utopian fantasies of ending disease and

famine competed with fears of mutated life

forms running amok. A suitably startling,

if less popcorn-worthy, event occurred in

October 1980, when the promise of DNA

modification raised US$35 million in a

landmark initial public offering (IPO),

which saw the fastest stock-price rise in the

markets history.

The record-breaking IPO was that of

Genentech, a small company based in San

Francisco, California, whose plan was to

produce drugs using recombinant DNA

technology. This was the first commercial

manipulation of DNA and the first sale of

biological science as a commodity in its

own right. The biotech industry was born.

Genentechs unique corporate structure,

which blurred the boundary between academia and industry, was swiftly imitated. The

sometimes uncomfortable entanglement of

publicly funded basic research with private

business enterprise persists to this day.

Genentech by science historian Sally

Smith Hughes gives a detailed account of

the founding and early years of the company. Much of the

material in the Although

book comes from Genentechs

oral histories col- business

lected by Hughes, model was

along with written groundbreaking,

archival material. the long-term

Hughess book is strategy was a

not, however, a classic risk.

journalistic analysis of a unique and important company: it

is an account of the key players, as told to a

sincere admirer.

Nevertheless, Genentechs achievements in science, medicine and business

were momentous. One of the companys

co-founders, Herbert Boyer, a molecular

biologist at the University of California,

San Francisco, was at the time a leader in

the development of recombinant DNA

technology. Boyer and others had recently

discovered a means of reorganizing (recombining) the sequence of DNA molecules, and

were pursuing a method to use this engineered DNA to generate proteins. This had

profound implications

for drug production

and development.

Whereas most

drugs had been discovered by large-scale

screening of synthetic

chemicals, a handful, such as insulin,

were natural proteins

whose production in Genentech: The

the body was impaired Beginnings of

Biotech

in diseases such as dia- SALLY SMITH HUGHES

betes. Proteins have University of Chicago

exceptionally com- Press: 2011. 232 pp.

plex structures, and $25, 16

it is still too difficult

to routinely synthesize them from scratch.

Therapeutic proteins were at the time

sourced from animals organs and human

cadavers, making their supply and safety

unreliable. In theory, recombinant DNA

could provide a safe, consistent source of

this class of therapeutics.

Boyers group was working on a way to

coax bacterial cells to produce therapeutic

proteins from recombinant DNA. More

importantly, recombinant DNA presented

a means of designing drugs using the biological mechanisms of a particular disease,

which seemed to be an obvious advance

over the pharmaceutical industrys random

screening procedures. Hughes does not,

however, touch on any of this, leaving the

reader to wonder why recombinant DNA is

viewed as so useful.

The reasons the IPO was so successful,

and why that success was so shocking, are

also underdeveloped in the book. At the

time it went public, Genentech had the

intention of making pharmaceuticals but

had no actual drugs in the pipeline. What

it did have was a contract with Eli Lilly, the

largest producer of synthetic insulin. The

contract was the first of its kind: Eli Lilly

was not paying Genentech to produce insulin, nor licensing a method to do so, but was

paying it to do the basic scientific research

needed to develop a method. Never before

had an independent group of scientists

contracted with a forNATURE.COM

profit organization

For a review of the

to make basic scienUS biotech debate:

tific discoveries, nor

go.nature.com/yv1ffo

had a publicly traded

4 5 6 | NAT U R E | VO L 4 7 8 | 2 7 O C T O B E R 2 0 1 1

2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

company offered research as its sole source

of revenue.

A patent on recombinant DNA techniques was granted in 1980 to Stanford University, California, and to the University of

California, where Boyer and his colleagues

had developed the technology. The assurance of intellectual-property protection for

genetic-engineering methods and products

encouraged the explosion of the biotechnology sector, as academic researchers began to

independently commercialize their findings.

The now commonplace practice of scientists

maintaining ties to both universities and

their own associated companies, along with

the conflicts it creates, comes directly from

Genentechs initial arrangement.

Although Genentechs business model was

groundbreaking in its mechanics, the longterm strategy was a classic risk. Genentechs

insulin was intended to be the Gutenberg

Bible of recombinant DNA technology an

established product made in a new way with

a guaranteed market. Yet the route between

basic knowledge of a disease process and an

effective therapy is punishing, and many

subsequent designer drugs generated using

the method proved not to be viable.

Rational drug design has not overtaken

traditional drug-discovery approaches, and

biotechnology development is shifting back

to large pharmaceutical companies, which

can hedge risk internally although the

future of drug discovery is a legitimate concern. Genentech itself is now wholly owned

by Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche.

The scant objectivity, the somewhat

plodding chronology of unfolding events

and the sparse explanations of technical

terminology in Hughess account aside,

Genentechs story remains a compelling

one. It neatly reveals the divergent challenges of basic science, medical science

and business, and despite its novelty, the

tale illustrates several enduring principles

of science and markets.

In shifting genetic-engineering research

from academia to industry, Genentech

and the industry it founded accelerated

the development and distribution of medically and agriculturally valuable products. It

triggered practical decisions on policy and

regulation, while effectively sidestepping

philosophical and ethical questions about

the uses of DNA: the market would decide

what DNA should be used for. Genentechs

business model shunted private money

directly into basic research, drew investors into basic science and academic scientists into business. Even as the industry

reorganizes, these relationships remain.

Linnaea Ostroff is a researcher at the

Center for Neural Science, New York

University, New York 10003, USA.

e-mail: lostroff@nyu.edu

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Black SigatokaDokument2 SeitenBlack SigatokaLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applications Guide 2021 (Oxford Brookes Careers)Dokument82 SeitenApplications Guide 2021 (Oxford Brookes Careers)LALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application Forms Guide: Tips for Completing Job AppsDokument15 SeitenApplication Forms Guide: Tips for Completing Job AppsLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nitrogen Fertilization and Stress Factors Drive Shifts in Microbial Diversity in Soils and PlantsDokument25 SeitenNitrogen Fertilization and Stress Factors Drive Shifts in Microbial Diversity in Soils and PlantsLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpreting Compost AnalysesDokument10 SeitenInterpreting Compost AnalysesLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applications Guide 2021 Covering LettersDokument8 SeitenApplications Guide 2021 Covering LettersLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume and Cover Letters - MastersDokument11 SeitenResume and Cover Letters - MastersLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development of An Influenza Virus Vaccine Using T-Wageningen University and Research 14323Dokument144 SeitenDevelopment of An Influenza Virus Vaccine Using T-Wageningen University and Research 14323LALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume and Cover Letter ExamplesDokument27 SeitenResume and Cover Letter ExamplesAnnisa Nur HarwiningtyasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insect Cell Culture Fundamental and Applied Aspects 2002Dokument303 SeitenInsect Cell Culture Fundamental and Applied Aspects 2002LALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biological Control: Tatiana Z. Cuellar-Gaviria, Lina M. Gonz Alez-Jaramillo, Valeska Villegas-EscobarDokument10 SeitenBiological Control: Tatiana Z. Cuellar-Gaviria, Lina M. Gonz Alez-Jaramillo, Valeska Villegas-EscobarLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Standard CompostDokument42 SeitenStandard CompostkrystynutaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Metode KuadranDokument28 SeitenJurnal Metode KuadranSandii Achmad ApriliantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plant Analysis Sample InformationDokument1 SeitePlant Analysis Sample InformationLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Composting Parameters and Compost Quality A Literature ReviewDokument21 SeitenComposting Parameters and Compost Quality A Literature ReviewLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- FAO - Future of Food and Agriculture PDFDokument180 SeitenFAO - Future of Food and Agriculture PDFĒl BaskoutaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plant Materials PhotographyDokument10 SeitenPlant Materials PhotographyLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Photography As A Tool of Research and DocumentationDokument7 SeitenPhotography As A Tool of Research and DocumentationLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2. GRACEnet Plant Sampling Protocols PDFDokument10 SeitenChapter 2. GRACEnet Plant Sampling Protocols PDFtolecahbagusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pnaar208 PDFDokument690 SeitenPnaar208 PDFIsbakhul LailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plant Materials PhotographyDokument10 SeitenPlant Materials PhotographyLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Photography As A Tool of Research and DocumentationDokument7 SeitenPhotography As A Tool of Research and DocumentationLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plant Analysis Sample InformationDokument1 SeitePlant Analysis Sample InformationLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- A-I4324e FAO ReportDokument66 SeitenA-I4324e FAO ReportAnonymous 6OPLC9UNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2. GRACEnet Plant Sampling Protocols PDFDokument10 SeitenChapter 2. GRACEnet Plant Sampling Protocols PDFtolecahbagusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Market MonitorDokument18 SeitenMarket MonitorLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2. GRACEnet Plant Sampling Protocols PDFDokument10 SeitenChapter 2. GRACEnet Plant Sampling Protocols PDFtolecahbagusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Growing For The Future Supporting Sustainable Agriculture With A New Generation of Biologically Sourced Tools For Plant NutritionDokument16 SeitenGrowing For The Future Supporting Sustainable Agriculture With A New Generation of Biologically Sourced Tools For Plant NutritionLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample - Global Liquid Fertilizer Market (2018 - 2023) - Mordor IntelligenceDokument28 SeitenSample - Global Liquid Fertilizer Market (2018 - 2023) - Mordor IntelligenceLALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Fertilizer Hotspots and Their Prospects For 2019Dokument5 SeitenGlobal Fertilizer Hotspots and Their Prospects For 2019LALUKISNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- A Plant-Growth Promoting RhizobacteriumDokument7 SeitenA Plant-Growth Promoting RhizobacteriumdanyjorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Welfare Administrartion McqsDokument2 SeitenSocial Welfare Administrartion McqsAbd ur Rehman Vlogs & VideosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perioperative NursingDokument8 SeitenPerioperative NursingGil Platon Soriano100% (3)

- Tingkat KesadaranDokument16 SeitenTingkat KesadaranShinta NurjanahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Tracheobronchitis Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentDokument2 SeitenAcute Tracheobronchitis Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentNicole Shannon CariñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Sleep Disorders and Their ClassificationDokument6 SeitenUnderstanding Sleep Disorders and Their ClassificationAh BoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- College Women's Experiences With Physically Forced, Alcohol - or Other Drug-Enabled, and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Before and Since Entering CollegeDokument12 SeitenCollege Women's Experiences With Physically Forced, Alcohol - or Other Drug-Enabled, and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Before and Since Entering CollegeGlennKesslerWP100% (1)

- PE GCSE Revision Quiz - Updated With AnswersDokument40 SeitenPE GCSE Revision Quiz - Updated With AnswersmohitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gurr2011-Probleme Psihologice Dupa Atac CerebralDokument9 SeitenGurr2011-Probleme Psihologice Dupa Atac CerebralPaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tradition With A Future: Solutions For Operative HysterosDokument16 SeitenTradition With A Future: Solutions For Operative Hysterosأحمد قائدNoch keine Bewertungen

- OrthodonticsDokument9 SeitenOrthodonticsReda IsmaeelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legalizing abortion in the Philippines for women's health and rightsDokument2 SeitenLegalizing abortion in the Philippines for women's health and rightsRosario Antoniete R. Cabilin100% (1)

- Co General InformationDokument13 SeitenCo General InformationAndianto IndrawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Swollen Feet During PregnancyDokument2 SeitenSwollen Feet During PregnancyDede YasminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 4Dokument107 SeitenModule 4roseannurakNoch keine Bewertungen

- L Sit ProgramDokument23 SeitenL Sit Programdebo100% (1)

- Nursing Assessment 1Dokument70 SeitenNursing Assessment 1Amira AttyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 798 3072 1 PBDokument12 Seiten798 3072 1 PBMariana RitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Gatekeeping As A Function of Role FidelityDokument2 SeitenProfessional Gatekeeping As A Function of Role FidelityNURSETOPNOTCHER100% (3)

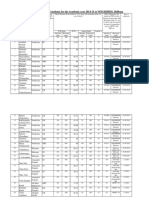

- Admission For 1st Year MBBS Students For The Academic Year 2014-2015Dokument10 SeitenAdmission For 1st Year MBBS Students For The Academic Year 2014-2015Guma KipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatric Malignant Bone TumoursDokument28 SeitenPediatric Malignant Bone TumourscorneliusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tailored Health Plans Table of CoverDokument22 SeitenTailored Health Plans Table of CoverAneesh PrabhakaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practitioner Review of Treatments for AutismDokument18 SeitenPractitioner Review of Treatments for AutismAlexandra AddaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EV3110 SIA Group ReportDokument38 SeitenEV3110 SIA Group ReportWill MyatNoch keine Bewertungen

- TuDokument382 SeitenTuAndra NiculaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIDDLE ENGLISH TEST HEALTH VOCATIONAL HIGH SCHOOLDokument4 SeitenMIDDLE ENGLISH TEST HEALTH VOCATIONAL HIGH SCHOOLZaenul WafaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Getting HSE Right A Guide For BP Managers 2001Dokument62 SeitenGetting HSE Right A Guide For BP Managers 2001Muhammad Labib Subhani0% (1)

- 12 Core FunctionsDokument106 Seiten12 Core FunctionsEmilyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A6013 v1 SD Influenza Ag BrochureDokument2 SeitenA6013 v1 SD Influenza Ag BrochureYunescka MorenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume - K MaclinDokument3 SeitenResume - K Maclinapi-378209869Noch keine Bewertungen