Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Power of Map

Hochgeladen von

vimipaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Power of Map

Hochgeladen von

vimipaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Seeing Through Maps:

The Power of Images to Shape Our World View

by Ward L. Kaiser & Denis Wood

ODT Inc., Amherst, MA ($19.95)

1-800-736-1293

Chapter One: The Multiple Truths

of the Mappable World

Two People, Two Feet Apart

What is the truth? It seems so simple. But when we try

to put it into words, it turns out to be much more complex.

Our dictionary says that truth is: Conformity to

knowledge, fact, actuality, or logic. That seems to help

until we try to say what knowledge is. Or facts.

Truth is most commonly used to mean correspondence

with facts or with what actually occurred, our dictionary

goes on. But when the police officer asks, What

happened? at the scene of even the simplest fenderbender, the officer never hears just one story. If facts were

straightforward we wouldnt need juries to determine

them.

The truth can seem awfully slippery at times.

At other times good sense rebels. Of course the truth

exists! We did have lunch last Thursday. It is a simple

fact.

But is it?

We did have lunch last Thursday.

Of course we sat in different chairs and these were sort

of angled to the table. Because of this one of us looked at

the other against a background of geraniums in coffee cans

and birds at a feeder in the dogwood tree; the other against

a background of the house next door and thunderhead

clouds in the summer sky above it.

What at first appears to be one thing the two of us

having lunch dissolves into two different scenes. Even

at a single moment in the meal different things are going

on. Sometimes they are so different we can see the other

persons eyes have drifted from the table. Ward has moved

with his eyes to something going on in the tree behind

Denis, or Denis has moved with his eyes to something

going on in the driveway behind Ward. Then we have to

reorient ourselves to the reality of the other by turning our

chairs to more squarely face each other.

Sometimes one of us sees something the other misses

completely, a bird at the feeder (and by the time the other

turns it is gone); or a kid doing something on a skateboard

(and the other turns, but he is too late). Then one persons

experience of lunch includes that event. The others

doesnt.

These differences in the experience of lunch result from

no more than a foot or two between our chairs and a

o

difference in orientation of maybe 90 . We can add to this

our different backgrounds, our different professions, different styles of thinking, and all the rest of it. Then, despite

everything we share, even of this simple meal it becomes

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

hard to say that this was that, and that was this. This is true

even in the moment, much less in the mind, or in the

memory a day, a week, a month or longer later.

But, damnit! We did have lunch together.

Sure, okay, if thats all you want to say: we had lunch.

There may be something we can call the truth if we keep

it so simple it doesnt matter.

Two Peoples, a World Apart

Two people, two feet apart. What if theyd been two

peoples a world apart? What if theyd been inhabitants of

New York and Beijing contemplating the U.S. bombing of

the Chinese embassy in Belgrade?

If all we can say of the truth is that bombs fell on a

building we might as well say nothing. Because it is not

about that. Thats ... past. It is about now and tomorrow. It

is about who will apologize (if anyone) to whom? It is about

what was really going on, and if this were a sign what it is a

sign of, and is it reasonable to have bombs? It is about what

life means if it can end this way. It is about stuff like that.

Its hot out here, one says.

It sure is, says the other.

Its this here global warming, says the first, too many

cars.

Bullshit, says the second.

It was easy to agree about it being hot, but attributing the heat to the cars implies a course of corrective

action. That raises the stakes. Suddenly it is a matter of

perception. Is it really hotter than it used to be? Or is

this a perspective effect? If it is hotter, is this usual or

unusual. If unusual, did people cause it? If we did, what

can we do about it?

You might ask, Well, what about someone across the

street watching the two of you having lunch? Wouldnt

they have an objective view? What about the UN

perspective on the bombing? What does science have to say

about global warming?

And, yes, each has its truth too, but there are three

truths now instead of two. Three truths ... or more. The

UN scarcely speaks in a single voice, and in the case of

science speaking about global warming were talking about

dozens and dozens of truths.

How many can we stand?

How do we act if we dont know whats true? Isnt life

hard enough already without adding to it the uncertainty

of there being many truths or maybe even none at all?

Frankly, life is hard enough already without pretending

it is only one true thing.

We were lost. A security guard at Duke University in Durham, North

Carolina, drew this map of the best way to get from Duke to Angier Avenue.

(1993).

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

true. The guard could have been irritated by our presence

and drawn a map intended to mislead us. (People have

What does this have to do with maps?

been known to do such things.) Or the guard could

Maps are descriptions of the way things are. They are a

simply have been mistaken about which street went

lot like the answers people

where.

give police at the scene of

Is his map complete? It is

an accident. Questions of

complete enough. It is not a

truth are never far away.

complete map of Durham.

We ask the same things

It is not even a complete

about maps we ask about

map of Durham streets. But

any description. How

it included everything we

true? How complete? How

needed to get from Duke to

accurate? How precise?

Angier Avenue.

The answers depend on

How accurate is it?

our purposes, what we need

Again, it is accurate

the description for.

enough. As a matter of fact,

On page two is a map a

Angier Avenue doesnt T

guard made to show us how

into Ellis Road. It crosses it.

to

get

from

Duke

But this didnt matter if we

University, in Durham,

were following the map.

North Carolina, to an auto

Is it precise? Not very.

repair shop on Angier

On one part of the map an

Avenue. It brings instituinch equals a couple of

This is a modern outline reconstruction of the 1569 map on which Gerardus

tions (Duke, Durham Tech), Mercator introduced his famous projection. Notice the way the rectangles hundred yards. On another

roads (NC 147, Briggs forming the grid get longer and longer as you move toward the North and it equals a couple of miles.

Avenue), and

landmarks South Poles. A redrawn version of his actual map is on the next page.

But again, it was precise

(a bridge, the railroad

enough!

tracks) together to form a sequence of instructions: Get

The guards map perfectly fulfilled its purpose. It was

off 147 at the Briggs Avenue exit just past Durham Tech,

perfect. The guard managed this by selecting from

is what the map says, And where Briggs dead ends, turn

everything he knew about Durham only what was

right ...

necessary to his purpose: to guide us where we wanted

Is it true? As a matter of fact it got us exactly where we

to go.

wanted to go, so it was true enough. It need not have been

Maps Are Descriptions Too

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

them world maps), this is no more a map of the world

than the guards was a map of Durham.

All Maps Are Selective

This isnt obvious at all.

But first, how else to call such a map? No other name is

Every map is a purposeful selection from everything that is

quite as convenient, and everyone calls it a world map, so

known, bent to the mapmakwe will too. But, as we do,

ers ends. Every map serves a

were going to keep in mind

purpose. Every map advances

that a great deal is missing.

an interest.

Often whats missing is a clue

This is easy to see in a

to the purpose the map is servmap like the one we have

ing.

been looking at which was

In this case, both of the

drawn with the special purearths poles are missing. A

pose of helping us visualize

lot of Antarctica is missing

instructions: Its kind of

too. So are all signs of relief:

complicated, the guard had

there are no mountains,

said as he put pen to paper.

valleys or plains, neither on

It is not so easy to see the

the land nor beneath the sea.

purpose in an ordinary map

There is no atmosphere

of the world like our next

either. Certainly there are no

example.

clouds. For that matter there

This is a redrawing of the map Gerhardus Mercator published in 1569 to preA world map like this sent his new projection. The original is too hard to reproduce. The title reads, is no sign of life, neither vegseems to have no purpose. in English, A New and Enlarged Description of the Earth With Corrections etable nor animal. There is

Or it seems to be ready to for Use in Navigation. Its intended use could not be more clearly spelled out. no sign of humans either, no

serve any purpose you might

countries, no Cairo, New

bring to it. For this reason such maps are often called

York or Mexico City, no Great Wall of China.

general purpose maps in an effort to differentiate them

It is hardly, in other words, the world. So what is it?

from special purpose maps like the one the guard drew.

At first thought it may seem to be a map of land and

But as we will see, there are no general purpose maps.

water. But when you think about it, too much water lies on

Every map serves a specific purpose. Every map

the land for this to be a map of water. There are literally

advances an interest.

tons of water, for instance, in the ice that lies over

We should have put world map in quotation marks.

Antarctica and Greenland. There are tons of water in the

Though this is how we talk about maps like this (we call

atmosphere too. So it is not a map of land and water. It has

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

to be about something else.

As with the truth, it seems simple. But when you try to

put it into words, it turns out to be hard. In fact, the map

is not at all what it seems. Even in its up-dated form (see

page 6) the map is actually still a piece of history. It

reminds us that when it was made, people crossed oceans

in sailing ships. A good description of this maps subject

would be, Places where ships will float and places where

they wont. This still isnt quite right. Even modern icebreakers get stuck in the solid ice of the Arctic Ocean.

Sailing ships never got into that ice at all.

All Maps Have a Purpose

But the sailable world is what this map is paying

attention to. It is a map for a world of sailors. It should

not surprise us, then, that the way the map shows the

world should reflect the interests of sailors too. The maps

on pages 3 and 6 are modern versions of one Gerhardus

Mercator made in 1569. He called his map, A New and

Enlarged Description of the Earth With Corrections for

Use in Navigation. His title was very precise about the

maps purpose, and right over North America he

engraved a long description of how he made it.

We will have much more to say about this map further

on. Whats important here, where were concerned with

the purposes maps serve, is what Mercators map was for.

The map made it possible for sailors to draw a straight line

to their destination and sail along it. This is because any

straight line drawn on Mercators map is a line of constant

compass bearing. Youd draw a line to your destination, set

your compass to the bearing of the line, follow it and,

making allowances for winds and tides, get where you were

going.

Mercators work was not appreciated right away. For one

thing, the map was too different at a time when sailors put

a great deal of faith in tradition. For another, the map was

too small to be of much practical use. It wasnt until the

ideas behind Mercators map became understood and

accepted, and until the map was redrawn as a series of

regional sea charts, that his work became popular.

In the 18th century when world travel became more

common, the use of Mercators map became more

common too. In that

increasingly scientific

Map Words

age the maps technical practicality gave it

Charts: A chart is a map

great authority. It was

designed for navigation.

in the 18th century

There are coastal charts,

that Mercators map

harbor charts, nautical charts

began to be seen as the

for use at sea and aeronautical

world map, essentially

charts for flying.

because it was the map

of the seaman, the

map of the navigator, the map of the professional world

traveler. As Western nations made themselves into colonial powers, Mercators map of the world came to be

seen as an important icon of Western superiority.

A Maps Quality Is Related To Its Purpose

The Mercator as an icon of Western superiority is

something else we will have a lot to say about further on.

Here our point is that this famous, popular, and

apparently general purpose map of the world turns out

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

to have been created to serve a very special purpose. It is

a purpose almost as special as the purpose served by the

The Mercator projection makes Europe look larger than South America. In fact,

Europe only has 3.8 million square miles and there are 6.9 million square miles

in South America. Of course, the projection was never designed to facilitate the

comparison of areas.

guards map. In fact, both maps have similar purposes.

Both are about helping you get where you are going.

How true is the Mercator? A lot of people think it is

not very true. To see what they are talking about, do

this: hold the modern version of the Mercator up to a

globe.

On the globe it is obvious that Mexico is larger than

Alaska, but on the Mercator it looks like Alaska is three

times the size of Mexico. On the globe you can see that

Africa is significantly larger than North America, but on

the Mercator it is the other way around. On the globe

South America can be seen to be almost twice as large

as Europe, but on the Mercator Europe seems to be

larger than South America.

The proportions of places on the globe are not the

proportions shown on the Mercator. On the Mercator

places closer to the north and south poles are

proportionally larger often much larger than

places closer to the equator.

How to think about this? Our dictionary says that to

distort something is, To twist out of a proper or natural

relation of parts, and in this simple, straightforward

sense Mercators map distorts the sizes of places on the

globe. But my dictionary goes on to say that to distort is,

To cast false light on, alter misleadingly, misrepresent.

In this second sense, the twisting out of a proper

relation is intended to mislead. The problem is that

these two senses of distort are often confused.

Does the Mercator mislead? It so happens that it is

impossible to make compass bearings straight lines on the

same map that gives places their proper proportions. It is

just not possible. To show the one, the other has to be

twisted out of a proper relation of parts. No map can

show both these things together.

To show one truth you have to distort another. This is

one good reason we need so many truths.

In our case this is because a world map is a

two-dimensional image of a three-dimensional globe.

There simply is no way to squash the globe into a plane

without losing something true about the globe. A

simple example is the way you can run your finger around

and around the globe. You cant do this on the Mercator

simply because of its edges. This is a crude illustration but

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

it gets to the heart of the matter: the map is not the

globe.

What this means is that every map is a view of the

globe. From this perspective, different maps are a lot like

the different views the two of us had of lunch, different,

because we were focused on different things, but equally

valid. Different maps are like telling a story, but from

different points of view.

Another way of saying this is that different maps

amount to different selections from what is available to

be shown in a medium where you cannot show

everything at once. What was true about the map the

Lerwick

Halifax

Part of the North Atlantic Ocean on Mercators projection showing the line of constant compass bearing (straight) and the great circle route (curved) between

Lerwick and Halifax. Although it shows up as longer on this projection, the great

circle route is shorter on the globe. A composite line composed of little short lines

of constanrt compass bearing has been fitted to the great circle route. These are

what a pilot would follow.

guard at Duke made is true about all maps: all maps are

selections from everything that is known, bent to the

mapmakers purpose.

Because it was no part of Mercators purpose to give the

proper proportions of places on the globe, it is not fair to

imply that his map casts a false light on, or misleadingly

alters, them. The loss of proportionality was an unavoidable

consequence of Mercators purpose to make compass

bearings straight lines. This loss of proportionality, most

serious in the infrequently traveled polar regions, was of

no practical importance for navigation, just as the lack of

proportionality in distances on the guards map was of no

practical importance for us.

Furthermore, when the Mercator was applied in a series

of regional sea charts as intended, the distortion was greatly reduced. Mercators purpose was to help sailors plot their

courses across the ocean, and for that purpose his map worked.

It still does.

As people require more than one truth, so sailing

requires more than a single view of the world. As useful as

the Mercator is, it could not be used for navigation by itself.

No single map could ever suffice. For one thing, no map of

the world could ever be sufficiently detailed for the careful

sailing required to take

a ship along a coast, or

Map Words

into and out of a harbor. For that purpose

Great circle: this is any line

navigators had lockthat, like the equator, divides a

ers filled with local

sphere into two equal halves.

charts. For another

The shortest distance between

thing, no navigator

two points on a sphere is part of

could

use

the

a great circle.

Mercator to plot his

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

shortest route. For that purpose he needed a map that

shows great circles as straight lines.

Showing great circles as straight lines is another thing

maps can do but not a map that makes compass bearings

straight lines, or that gives areas their proper proportions. This is another example of the fact that all maps

are selections from everything that is known, bent to the

mapmakers purpose. Like telling a story from different

points of view, each purpose requires a different map.

What is a great circle? It is any line that divides a

sphere into two equal halves. The equator is a great

circle. It divides the globe into northern and southern

hemispheres. While the shortest distance between two

points on a plane is a straight line, the shortest distance

between two points on a sphere is part of a great circle.

This is just another of those differences between planes

and spheres that complicates the world of maps.

You may already know about great circle routes. Take

another look at a globe. If you were to fly from New York

to Beijing would you head east over the Atlantic, Europe

and all of Asia? Or west across the U.S. and the Pacific?

Or would you fly north, more or less over the pole?

As you can see (and if you want to make sure you can

use a piece of thread or string to measure it), the shortest

route (by far!) goes over the pole. This is a great circle

route, a segment of a circle which if it were continued

would circle the globe and, like the equator, divide it in

two.

As you can also see, flying along the great circle route

from New York to Beijing you would be constantly

changing your bearing. First you would be flying north,

then west, then

Map Words

south.

The way navigators

Gnomonic: This is a kind of

work is to plot their

map that shows great circles as

route on a map that

straight lines.

shows great circle

routes as straight

Lambert conformal conic: this

lines. They can do

is a kind of map on which great

this on a kind of map

circles are close enough to

called the gnomonic.

straight lines to make it useful

Such maps do not

for aeronautical charts.

have a lot of other

useful characteristics,

so they are not much used. Since great circles are almost

straight on Lambert conformal conic maps, these are

increasingly used for this purpose, especially for

aeronautical charts.

Having laid out their route on such a map, the pilots

transfer it to a Mercator. Here they approximate the

route with a chain of straight line segments. They then

fly along these segments which, since they are straight

lines on a Mercator, are lines of constant compass bearing.

This is pretty much how ships navigate too. Of course

today this is all done by computers.

To Repeat: A Maps Quality Is a Function of Its

Purpose

Would it be fair to say Mercators world map lied

because it lacked detail about the coasts and harbors?

Not really. If you want to show the worlds 197 million

square miles on a chart thats twelve feet square, some

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

details are going to be

left out. It is like

Map Words

telling a story. If

someone wants it told

Generalization: When mapin 60 seconds the

makers smooth out coastlines

details that would

or take the kinks out of rivers

make it last an hour

to give the general idea, as

have to go. You just

when they are showing the

hit the main points.

whole Mississippi or the whole

This isnt lying. It is

East Coast of North America,

not incompleteness

they call it a generalization.

either. When mapmakers just hit the

main points, ignoring, say, all the tiny twists and turns of

a coastline, they call it generalization.

Similarly, Mercators failure to give places their proper proportions doesnt amount to lying, nor is it fair to

think about it as inaccurate. The changes in proportionality are smooth, continuous and predictable. They are necessary consequences of the manipulations Mercator had to

carry out in order to make compass bearings straight lines.

To make all this clearer, here is another world map.

And what a different world!

This is called the Peters map, after Arno Peters who

introduced it in 1974. Unlike Mercator whose purpose

was to help sailors, Peterss purpose was to help the rest

of us. Peters believed that widespread use of Mercator

maps for all kinds of purposes that had nothing to do

with navigation had built up in our minds a greatly

distorted image of the world.

It is fair to say Peters was especially concerned about

our image of Africa and those other countries around

the equator that were given short-shrift as a

consequence of the Mercator projection. On a Mercator

the former Soviet Union is much larger than Africa.

Wouldnt people looking at such a map imagine that the

Soviet Union was much more important than Africa?

Africa is actually about the size of the former Soviet

Union and the United States combined. Africa is

substantially larger than the United States and the current

Russia. If size were what mattered Africa would rank

second in importance only to Asia. Europe would compete

with Australia for last place. There is no question that the

Peters makes this much more evident than the Mercator.

What a different world this seems to be. This is a projection of the world that gives

areas their true relative size. You can easily see how much larger South America

is than Europe. On the other hand, compass bearings are not straight on this map.

Maps really are like points of view.

10

One: The Multiple Truths of the Mappable World

A head drawn one one projection (Robinsons) has been transferred to the Mercator (center left) and a sinusoidal (center right) and finally to a Mollweide (far right).

The natural profile could have been drawn on any of these and then plotted on the others. This is just a way of getting of sense of what different projections do.

Which map is right?

Theyre both right. Theyre just right about different

things. But again, theyre both wrong too.

Focus on the shapes of the continents. First hold the Peters

up next to a globe. Is Africa really so tall and skinny? Is Alaska

so stringy? The shapes on the Peters are precisely as distorted

as sizes on the Mercator. The loss of good shape, what mapmakers call conformality, is

one of the things Peters had

to sacrifice to keep the areas

Map Words

of places in their proper proportions.

Conformality: this is the

On the other hand, the

ability of a map to perserve

Mercator does show true

angular relationships as they

shapes. This is something

exist on the globe. What

we will have more to say

this means is that the map

about later on, but if you

can show shapes the way

compare shapes on the

they are. A conformal map

Mercator with those on the

cannot show areas in their

globe you will see that if

true size.

shapes are true, they are

true in a very peculiar way.

In fact, shapes are only locally true on the Mercator.

That is, shapes are true in this little spot here, and

shapes are true in that little spot there. But because sizes

change so drastically, when you look at something as big

as a continent you have one small true shape toward the

equator (say Mexico), and another small true shape near

the pole (say Alaska), but the latter is so many times larger

than the former, that when you put them together, the

shape of North America as a whole is not right.

Its as if you were to draw a picture of someones face,

and you got the shape of the chin right, and you got the

shape of the forehead right, but you made the forehead

ten times larger than the chin. Then even though every

part was right, the shape of the whole face would seem

to be wrong.

Shapes get truer and truer the more you zoom in on

the Mercator. This is why the Mercator is so widely used

today for mapping small areas in great detail.

Chapter Title Placeholder

11

Each Map Has Its Own Point of View

So which map should you use?

You should use the map that serves your purpose. Only

when you are given a maps purpose, can the maps rightness its truth be assessed.

If youre flying across the ocean the Mercator is going

to be useful, but if youre trying to compare the sizes of

places you will want to use the Peters. If youre trying to

find your way from Duke to Angier Avenue, neither will

be the slightest help.

We need a local point of view to get across town. We

need a comparative perspective to get sizes right. We

need the point of view of a compass to fly across the

ocean.

Every map takes a point of view. No map can show

everything at once any more than the two of us could see

the same things at the same time at lunch. At the very

least, if we were to see each other, we couldnt see

ourselves! Besides, sometimes one of us was in the

kitchen getting the coffee, or visiting the bathroom.

Then our experiences of the meal were sharply divided.

One of us might ask, Remember that bird a minute ago

that and the other will say, No, I was in the kitchen

getting the coffee, but you told me about it. Yet we did

have lunch together.

The map that is, as it were, getting the coffee (making

compass bearings straight) cant be sitting on the porch

taking in the scene (showing places in their proper

proportions). Yet there is only one planet.

It takes many different eyes to see it all, and many different maps to show it. That this is a strength, not a

weakness, is what the rest of this book is about.

Seeing Through Maps:

The Power of Images to

Shape Our World View

by Ward L. Kaiser & Denis Wood

ODT Inc., Amherst, MA ($19.95)

1-800-736-1293

to be published summer 2001

2001. ODT, Inc. All rights reserved

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Chanting Book Vol 1 WebDokument155 SeitenChanting Book Vol 1 WebvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Structure of Introductions in Scientific Articles: Swales' CARS ModelDokument4 SeitenThe Structure of Introductions in Scientific Articles: Swales' CARS Modelvimipa0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Rhetorical Structure of IntroductionsDokument3 SeitenThe Rhetorical Structure of IntroductionsvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Florid Language in Indian EnglishDokument2 SeitenFlorid Language in Indian EnglishvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Authenticity of Early Buddhist TextsDokument158 SeitenThe Authenticity of Early Buddhist TextsPaulo VidalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Websites For WritersDokument7 SeitenWebsites For WritersvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Place of Logic Among The SciencesDokument5 SeitenThe Place of Logic Among The SciencesvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Concept of KnowledgeDokument60 SeitenConcept of KnowledgeVivian PaganuzziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Why Study PhilosophyDokument3 SeitenWhy Study PhilosophyvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Conditionals SummaryDokument5 SeitenConditionals SummaryIulian PopaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ask A PhilosopherDokument74 SeitenAsk A PhilosophervimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Take With A Pinch of Sodium ChlorideDokument3 SeitenTake With A Pinch of Sodium ChloridevimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aesthetics Some Basic IssuesDokument1 SeiteAesthetics Some Basic IssuesvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Are 26 Million Africans Dying of AidsDokument6 SeitenAre 26 Million Africans Dying of AidsvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Getting Knowledge About PeopleDokument2 SeitenGetting Knowledge About PeoplevimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Getting Knowledge About PeopleDokument2 SeitenGetting Knowledge About PeoplevimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Meaning of SwayambuDokument125 SeitenThe Meaning of SwayambuvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Freedom of The Will - Petter HarveyDokument65 SeitenFreedom of The Will - Petter HarveyDhamma ThoughtNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of NepalDokument4 SeitenHistory of NepalvimipaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gps and Weapons Tech. Seminar Report.Dokument27 SeitenGps and Weapons Tech. Seminar Report.jagadish shivarajNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- SBVT - Ils U or Loc U Rwy 24 - Iac - 20231130Dokument1 SeiteSBVT - Ils U or Loc U Rwy 24 - Iac - 20231130João Pedro Santos da CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

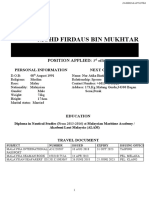

- Mohd Firdaus Bin Mukhtar: Position AppliedDokument3 SeitenMohd Firdaus Bin Mukhtar: Position AppliedRara Lens HouseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gps Lecture NotesDokument101 SeitenGps Lecture NotesRocking ChakravarthyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Animal Migrations: Eco-Meet Study GuideDokument13 SeitenAnimal Migrations: Eco-Meet Study GuideDivya BajpaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab 4Dokument10 SeitenLab 4nilimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blind Pilotage: A Brief by Lance GrindleyDokument32 SeitenBlind Pilotage: A Brief by Lance GrindleyMegat Rambai Sr0% (1)

- NaviPac OnlineDokument100 SeitenNaviPac OnlineFadly saddamNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Wave Navigation Marshall Islands: in TheDokument12 SeitenWave Navigation Marshall Islands: in TheallanmartelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Magnetic and Gyro Compass and Steering Systems - B.J. WaDokument71 SeitenMagnetic and Gyro Compass and Steering Systems - B.J. Wamaneesh100% (1)

- Land Navigation Handbook1Dokument66 SeitenLand Navigation Handbook1Pedro GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- JEPP's Briefing - The Chart Clinic - 8th - Airway Designation SymbolsDokument2 SeitenJEPP's Briefing - The Chart Clinic - 8th - Airway Designation SymbolsMarcos BragaNoch keine Bewertungen

- VNAV Descent VBI and Vert DevDokument3 SeitenVNAV Descent VBI and Vert DevcypNoch keine Bewertungen

- 27snii15 Week27 2015Dokument151 Seiten27snii15 Week27 2015Kunal SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use of GPSDokument52 SeitenUse of GPSAbel MathewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dana Tutorial On Coordinate SystemsDokument14 SeitenDana Tutorial On Coordinate SystemsSurvey_easyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boeing PBN OperationsDokument10 SeitenBoeing PBN Operationslubat2011100% (5)

- Acn MCQDokument52 SeitenAcn MCQBadal MachchharNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Coast Guard at WarDokument149 SeitenThe Coast Guard at WarLORANBillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- AIP Japan RJGG-AD2-24.2 Chubu Centrair IntlDokument37 SeitenAIP Japan RJGG-AD2-24.2 Chubu Centrair IntltommyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Egnos: European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service: Europe's First Contribution To Satellite NavigationDokument12 SeitenEgnos: European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service: Europe's First Contribution To Satellite NavigationalibucuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Global Wgs 84 CoordinateDokument3 SeitenThe Global Wgs 84 CoordinateBenedicta Dian AlfandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teste Codigo Automato ArduinoDokument15 SeitenTeste Codigo Automato ArduinoCrhistian IzaguirryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final PPTDokument32 SeitenFinal PPTShailendra RajputNoch keine Bewertungen

- Euroscope AliasDokument2 SeitenEuroscope AliaszirakanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zym GM23 5RDokument18 SeitenZym GM23 5RFabricio RubioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topographic Map of MaypearlDokument1 SeiteTopographic Map of MaypearlHistoricalMapsNoch keine Bewertungen

- EDSS 101 - Human Geography Activity 2Dokument3 SeitenEDSS 101 - Human Geography Activity 2Angeline Cristine DolzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sensors: An Indoor Navigation System For The Visually ImpairedDokument23 SeitenSensors: An Indoor Navigation System For The Visually ImpairedBaala ChandhrenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vor Dme and NDB DraftDokument5 SeitenVor Dme and NDB DraftJohn Kevin DiciembreNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearVon EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (23)

- Periodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincVon EverandPeriodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (137)

- The Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterVon EverandThe Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterNoch keine Bewertungen