Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Test Prescolar

Hochgeladen von

madtur77Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Test Prescolar

Hochgeladen von

madtur77Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ADAPTED PHYSICALACTIVITY QUARTERLY, 2000,17,78-94

O 2000 Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc.

A New Test for Assessing Preschool

Motor Development: DIAL-3

Carol Mardell-Czudnowski

Northern Illinois University

Dorothea S. Goldenberg

University of Illinois, Chicago

Recent research and legislation in the United States regarding assessment of

preschool children have guided the development of the latest version of the

Developmental Indicators for the Assessment of Learning, DIAL-3. This paper briefly describes the history of this test's previous two versions (DIAL,

1975 and DIAL-R, 1983, 1990) followed by a description of the research and

development of the motor items in DIAL-3. Then DIAL-3 is evaluated, using

the key features for selecting an appropriate preschool gross motor assessment instrument (Zittel, 1994). DIAL-3 meets all of the common criteria for a

technically adequate screening test.

Accurate motor assessment of young children with special needs is necessary for quality intervention.According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), this assessment should be completed by a multidisciplinary team

(Federal Register, 1997). Special educators, including adapted physical educators

and related service providers such as physical therapists, need to know about the

best instruments available for the screening and diagnosis of motoric problems in

young children.

Developmental screening should identify children who are at risk for developing various learning or behavior problems (Gredler, 1992; 1997). The term at

risk is widely used but ambiguous because risk is not static, standardized tests

generally are not effective predictors of risk, and children are not isolated entities

but develop within an ecological context (Gredler, 1992;Hrncir & Eisenhart, 1991;

Keogh & Speece, 1996).Additionally, Keogh and Speece (1996) found protective

factors, either within the child or the environment, that may compensate or outweigh the risks. Due to these problems, the concept of who is at risk varies. Another term often used as the end goal of screening is developmental delay. McLean,

Smith, McCormick, Schakel, and McEvoy (1991) define this term as a condition

Carol Mardell-Czudnowski is Professor Emeritus, Department of Educational Psychology, Counseling, and Special Education, Northern Illinois University. Dorothea S.

Goldenberg is with the Department of Psychiatry, Institute for Juvenile Research at the

University of Illinois, Chicago.

Preschool Motor Development

79

which represents a significant delay in the process of development. The child is

not slightly or momentarily lagging in development. Rather, development is significantly affected and, without special intervention, it is likely that educational

performance at school age will be affected. DIAL-3 is designed to identify both of

these populations of young children, keeping in mind the importance of the succeeding steps to diagnostically verify thedegree of risk or delay and its impact on

future developmental growth as well as academic programming (MardellCzudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998).

Accurate motor assessment requires instruments that meet key criteria. The

purpose of this paper is to describe ;specific test and evaluate it according to the

six criteria identified by Zittel (1994). Although this test covers the five developmental areas (motor, cognition, language, psychosocial, and self-help skills) mandated in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; Federal Register,

1997), this paper will be limited to the motor skills component.

Historical Development of DIAL and DIAL-R

A brief history of the first two versions, DIAL (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1975) and

DIAL-R (Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg, 1983, 1990) will be given since

each new version was built upon the previous one(s). More than a quarter of a

century ago, in 1971, the Illinois legislature passed two bills that required the development of a screening procedure that would identify young children with either

current or potential learning problems (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972). To meet

this challenge, the Illinois State Board of Education funded, through federal assistance for the education of handicapped children (Title VI, ESEA), a project that

resulted in the development and standardizationof a screening test known as DIAL

(Developmental Indicators for the Assessment of Learning).

The initial set of procedures and items (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972) was

developed by project staff and approved by a 20-member advisory board on the

basis of 10 criteria that were found in some tests, but no test at that time met all ten.

DIAL was designed to (a) be a screening test rather than a diagnostic test (relatively short, of a surface nature, and indicate the possibility of a variance in development); (b) cover the age range of 2.5 to 5.5 years; (c) be administered individually,

since this is the only way that gross motor skills, articulation, and receptive language can be assessed adequately, but in a group setting that simulates a typical

preschool or kindergarten classroom; (d) take about 30 min due to the frequent

difficulty of maintaining a young child's attention on activities that are not of his

or her choosing and the need to screen many children; (e) be multidimensional

(cover many areas of development); (f) be noncategorical and attempt to identify

at risk children regardless of the reason for the potential learning problem; (g) be

scored on the basis of observable performance rather than the subjective opinion

of the tester; (h) be process-oriented as well as product-oriented (i.e., evaluate how

a child does something in addition to the end result or score); (i) be applicable to

culturally different populations; and (j)be normed on a large stratified sample.

Thus, DIAL was normed on 4,356 children across the State of Illinois in the spring

of 1972, stratified by sex, race, size of the community, and socioeconomic level.

DIAL met all of the 10 criteria according to three independent external evaluators

(Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972). Materials were designed to meet the screening

criteria with some items presented one at a time on a format that resembles a

80

Mardell-Czudnowski and Goldenberg

telephone dial to reduce distraction. This format has remained as a unique feature

of all DIAL tests.

The theoretical basis for DIAL. and hence subseauent versions. was eclectic. Past and current theories and research findings were taken into consideration,

but the major thrust was examining what was being used in the early 70s to identify young children with special needs. There were many tests for young children

that preceded DIAL. Ninety-four instruments used for the identification of

prekindergarten high risk children were analyzed (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972,

1973) on the basis of age range (2-6 years); depth (screening or diagnostic); administrative factors (individual vs. group, test time, timed or untimed items, qualifications of person giving it); type of response (vocal or motoric); performance

factors (auditory discrimination, articulation, language, developmental, visual perception, motor, school readiness, social skills, self-concepts, conceptual skills);

and whether the tests were measurements requiring subjective judgment (rating

scale, interview, observation). From this analysis, six areas of behaviors were identified to be screened: sensory, motor, affective, social, conceptual, and language.

Normed data from the items within the tests were plotted to assist in determining

appropriate age ranges for each task.

The theoretical antecedents of motoric items for DIAL were based on the

early research by Gesell and Thompson (1938) and McGraw (1943), who had

established norms for motor skill development. Gesell (1952) postulated that all

mental life probably has a motor basis and a motor origin. Kephart (1960) labeled

the first interaction of a child and his environment as motor activity. Many researchers (Cratty, 1967; Dunsing & Kephart, 1965; Kephart, 1960) believed that

specific motor controls are a necessity for learning. By exploring and interacting

with the environment, a child receives stimulation and processes these responsive

patterns into learned actions. Thus, the importance of motor development became

an assessment priority in the development of DIAL. The delay of motor learning

and motor skills was viewed as a significant factor in the identification of children

with potential learning problems (Barsch & Rudell, 1962; Bryant, 1964; Karlin,

1957).

Motor development items on DIAL were formatted into two areas for ease

of assessment, gross motor and fine motor (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1975). Gross

motor behaviors were assessed more easily when the child was in an upright position, whereas fine motor behaviors were measured more easily while the child was

sitting at a table. In the gross motor area, tasks of throwing, catching, jumping,

hopping, skipping, standing still, and balancing were assessed. In the fine motor

area, tasks of visual matching, block building, cutting, copying of shapes and letters, finger touching, and hand clapping were assessed. Justification and developmental norms for all of these tasks were found in the literature (Mardell &

Goldenberg, 1972), but there were no established norms on previous tests for the

standing still item. In addition, all of the gross and fine motor tasks were statistically analyzed and found to be developmental (i.e., indicative of increased levels

of motor coordination as children grew older; Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972,1975).

Research conducted during the next 2 years confirmed the validity and reliability

of the items and procedures (Hall, Mardell, Wick, & Goldenberg, 1976). Additional validity and reliability studies are described elsewhere (Mardell-Czudnowslu,

1980; Wright & Masters, 1982).

Preschool Motor Development

81

DIAL was revised in 1983 as DIAL-R (Mardell-Czudnowski& Goldenberg,

1983). The revision maintained those features that were most valuable for screening young children while improving the predictability of the screening results. The

previous criteria were retained but others were added. Three changes in particular

affected every aspect of DIAL-R construction: (a) DIAL-R was standardized on a

national sample, whereas the DIAL standardization sample had been restricted to

the state of Illinois; (b) DIAL-R extended the age range to ages 2.0 to 6.0, whereas

the age range of DIAL was from 2.5 to 5.5; and (c) DIAL-R combined the gross

motor and fine motor items of DIAL into one area, motor. This change was made

for two reasons: (a) it reduced the weight of motoric items in the total score from

one half to one third, so it was comparable to the weight of either the concepts or

language items; and (b) it reduced the size of the screening team from four to three

operators, which was important from a practical point of view (Mardell-Czudnowski

& Goldenberg, 1983).

The seven items in gross motor and the eight items in fine motor were revised in the following manner. Throwing, standing still, balancing, and clapping

hands were deleted based on scoring problems and feedback from the field over

the decade of its use; catching, matching, and copying were revised to clarify scaring procedures;jumping, hopping, and skipping were combined into one item; and

building and cutting were revised only to accommodate for the extended age range.

Finally, one new item, writing name, was added as a school-related task identified

by nursery school, kindergarten, and f~st-gradeteachers. This item was administered only to children 4.0 and older.

The output of all eight motor items in DIAL-R is only motoric, while the

input for all motoric items is both visual and auditory. This was done to ensure the

children's understanding of how they were to respond independent of whether

they had the particular skill being assessed. Thus, even though they might not hear

or understand what was said (possibly due to a lack of comprehension in English),

they have an opportunity to see a demonstration of what is expected. For children

with a visual problem, other than total blindness, having the directions given

auditorially allows them to compensate to some degree.

DIAL-R was substantially modified in 1990 (Mardell-Czudnowski &

Goldenberg, 1990). In particular, the DIAL-R norms were reanalyzed, reliability

and validity data were expanded, a wider range of cut-off points was made available, and materials for training examiners were included in the test kit.

Development of DIALS

Since DIAL-R is widely used throughout the United States and in several other

countries (Australia, Taiwan, Canada, Hong Kong, Indonesia), the authors and

publisher decided to revise the DIAL-R test based on three considerations: (a)

norms must be kept current (less than 15 years old) to be valid (Salvia & Ysseldyke,

1998); (b) access to a free, appropriate, public education (FAPE) is now mandated

for eligible children of preschool age in all 50 states and several United States

territories (NEC*TAS, 1992), therefore children cannot be kept out of school because they did not pass a screening test; and (c) recent research suggests different

items may be more discriminatingin the early identification of at-risk children during

the preschool years. Again, the focus of this section will be on the motor items.

82

Mardell-Czudnowski and Goldenberg

Item Development

DIAL-3 continues to measure a subset of the most fundamental or basic skills that

are acquired by young children. The following is a list of general principles that

were adhered to in the development and selection of items: They should (a) be

developmentally appropriate, (b) be precursors of school success, (c) have enough

floor for the younger children, (d) be good discriminators, (e) be easy to administer, (0 be unambiguous to score, (g) cover the entire age range, and (h) be limited

to 10 min for the administration time of each area. Items were chosen that met the

majority of these principles and would be meaningful to children.

Children who may develop learning problems very often have difficulty with

their gross and fine motor movements. Johnson and Myklebust (1967) noted that

minor incoordination problems with tasks of buttoning and tying laces are observed in young children with learning disabilities. According to Smith (1991),

over 75 % of all poor readers have motor disturbances, but only 25 % of these

children have visual-motor disturbances. Therefore, motor weaknesses often are

not the result of underlying visual-perceptual deficits. A recent study by Fawcett

and Nicolson (1995) confirms that a number of children with dyslexia have persistent deficits in motor skills that continue into adolescence.

Descriptions of the 7 items in the motor area and the rationale for their inclusion in the DIAL-3 follow (Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998). The recommendations made by the National Association for the Education of Young

children (NAEYC) were followed for age-appropriateexpectations in specific tasks

(Bredekamp & Copple, 1997). Thus, by using entry and exit points throughout the

assessment, tasks that would be too difficult for younger children and cause unnecessary frustration and tasks that would be too simple for older children and

cause unnecessary boredom are avoided.

Item I - Catching. Catching is assessed by the child having four opportunities to catch a beanbag from a distance of 6 feet. In DIAL-R, the child had three

opportunities, but a one-handed catch was added to ensure appropriate difficulty

for 6-year-olds. Campbell (1985) suggested that to catch, the child needs the ability to predict the trajectory of an object. Normed data for catching were originally

found (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972) on three early childhood instruments: Denver Developmental Screening Test (Frankenburg & Dodds, 1968); Preschool Attainment Record (Doll, 1966); and Quick Screening Scale of Mental Development

(Banham, 1963). Additional norms developed as landmarks for pediatricians

(American Academy of Pediatrics. n.d.) were also utilized.

Item 2 - Jump, Hop, and Skip. Jump, Hop, and Skip consists of three separate tasks. First, the child is required to jump up to touch a beanbag held slightly

above his or her head. Campbell (1985) noted that to jump, the child needs the

ability to produce the proper velocity of body movement. Normed data for jumping were originally found (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972) on five early childhood

instruments: Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1968), Denver Developmental Screening Test (Frankenburg & Dodds, l968), Developmental Diagnosis (Gesell & Amatruda. 1947), Preschool Attainment Record (Doll, 1966), and

Quick Screening Scale of Mental Development (Banham, 1963).Additional norms

had been developed by Kephart (1960) and as landmarks by the American Academy of Pediatrics (n.d.).

The hopping task requires the child to hop six times on each leg. Normed

data for hopping were originally found (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972) on four

Preschool Motor Development

83

early childhood instruments: Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1968),

Denver Developmental Screening Test (Frankenburg & Dodds, 1968), Developmental Diagnosis (Gesell & Amatruda, 1947), and Preschool Attainment Record

(Doll, 1966).Additional norms had been developed by Kephart (1960) and as landmarks by the American Academy of Pediatrics (n.d.). A study of normal and atrisk 3- and 5-year-olds by Huttenlocher, Levine, Huttenlocher, and Gates (1990)

found only three neurological test items that distinguished between the two groups.

One was hopping, which supports its importance as a DIAL3 task. Hopping carries 80% of the item score, although it is only one of the three tasks within this

item. At ages 5 to 7, this task requires the ability to hop first on one leg and then on

the other.

The third task, skipping, requires the child to skip one or two times after

watching the operator do so (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972). Normed data for skipping were originally found (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972) on three early childhood instruments: Developmental Diagnosis (Gesell & Amatruda, 1947),Preschool

Attainment Record (Doll, 1966), and Quick Screening Scale of Mental Development (Banharn, 1963). Additional norms had been developed by Kephart (1960).

Although it is a complicated gross motor activity that requires coordinated bilateral use of the body, Hynd and Willis (1988) state that skipping emerges in normally developing children around the age of 4 to 5 years. When this task is

administered to 3-year-olds, as well as to older children, points are given for precursor behaviors to skipping (e.g., stephop, gallop).

Item 3 - Building. DIAL-R required the child to model the building of a

three-block tower, a three-block bridge, and a six-block pyramid, in addition to

building a six-block stairs from memory. DIAL-3 has the same first three structures but substitutes a six-block child figure built from a model, thus gaining a

more difficult task for the older child while eliminating memory as a factor. Normed

data for building were originally found (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972) on 10 early

childhood instruments: Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1968), Measurement of Intelligence of Infants and Young Children (Cattell, 1960), Denver

Developmental Screening Test (Frankenburg & Dodds, 1968), Developmental

Diagnosis (Gesell & Amatruda, 1947), Merrill Palmer Scales (Stutsman, 192648), Minnesota Preschool Scale (Goodenough, Maurer, & Van Wagenen, 1940),

Preschool Attainment Record (Doll, 1966), Quick Screening Scale of Mental Development (Banham, 1963), Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (Terman & Merrill,

1960), and Tests of Mental Development (Kuhlman, 1939).Additional norms had

been developed as landmarks by the American Academy of Pediatrics (n.d.). The

natural progression in block assembly from a tower to a bridge to more complicated structures was elaborately documented by Case (1985), justifying the continued inclusion of building as a strong developmental item.

Item 4 - Thumbs and Fingers. Thumbs and Fingers has two tasks. First, the

child is shown how to twiddle thumbs and then asked to repeat the movement. The

second task is one of motor sequencing. It requires touching each of the four fingers to the thumb in sequence without skipping a finger or repetitively touching a

finger. This task is often given as part of a standard neurological examination.

Normed data for finger agility were originally found (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972)

on one early childhood instrument: Merrill Palmer Scale (Stutsman, 1926-48).

Welsh, Pennington, and Groisser (199 1) reported this task to be related neurologically to verbal fluency and to be developmentally sensitive, with differences between 12-year-olds and adults. A similar task was part of both the original DIAL

84

Mardell-Czudnowski and Goldenberg

and DIAL-R, but twiddling thumbs was added to the DIAL-3 item for the younger

child.

Item 5 - Cutting. As on the DIAL-R, children are asked to cut snips, a

straight line, and a curved line. The older child (age 5 and up) also is asked to cut

out a figure of a dinosaur, a task new to DIAL-3. Normed data for cutting were

originally found (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1972) on five early childhood instruments: DevelopmentalDiagnosis (Gesell & Arnatruda, 1947),Merrill Palmer Scale

(Stutsman, 1926-48), Preschool Attainment Record (Doll, 1966), Tests of Mental

Development (Kuhlman, 1939), and Vineland Social Maturity Scale (Doll, 1935).

Cutting skills hold up well as a developmental item, based on both DIAL-R and

DIAL-3 data. Additionally, cutting is highly regarded by early childhood personnel as a school-related task and is enjoyed by young children as an activity.

Item 6 - Copying. The child is requested to copy four geometric shapes

and four letters. The eight figures contain vertical and horizontal strokes (developmentally easiest), diagonal strokes, and curves that meet lines (most difficult).All

eight figures are presented on the Dial format. Normed data for copying were

originally found on all of the early childhood instruments previously listed (Mardell

& Goldenberg, 1972).Fletcher and Satz (1982) found the use of the Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration (VMI; Beery, 1982), on which children copy

24 geometric figures and three other brief tests correctly predicted 85 % of kindergarten children who were problem readers 7 years later. Fowler and Cross (1986)

reached a similar conclusion about the value of copying as a predictor.

In addition, Simner (1994) has done considerable research on young children's

ability to copy letters and shapes. He has concluded that an excessive number of

copying errors (addition, omission, andlor misalignment of parts leading to a marked

distortion in the overall shape or form) appearing in samples of printing obtained

from 4- to 6-year-old children can be an extremely important warning sign of later

school failure. A 3-year follow-up study of 171 children by Simner (1989) showed

that form errors in printing, even as early as the start of prekindergarten, could be

scored reliably, remained stable over time, and were tied to performance in first

grade. Simner (1994) also investigated which shapes are most predictive of school

success and the manner in which they should be scored. Three of the four DIAL-3

shapes are on his list. He then applied his findings to two different groups of children and established that copying shapes is closely linked to school success. Smith

(1991) states that, on the basis of her research, copying ability is one of the most

consistent correlates of early math and reading success.

Item 7 - Writing Name. This item is a unique task in DIAL tests. A survey

of DIAL-R users indicated that Writing Name was an item they believed should be

kept on the basis that, in their experience, it is a measure of school success. Furthermore, in her research of children's development of writing, Sulzby (1990) found

the writing of one's name to be one of the landmarks along the path from scribbling to conventional writing. In addition, DIAL-R and DIAL3 data analyses show

a developmental progression in this skill. It is administered only to children 4-0 or

older, the ages at which it is a developmentally appropriate item (Bredekamp &

Copple, 1997).

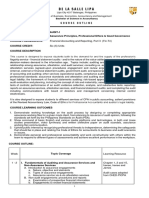

Content Analysis

The content analysis that had been performed for the DIAL and DIAL-R was reviewed and modified to reflect the abilities the items were intended to assess such

Preschool Motor Development

85

as visual motor integration, short term memory, previous learned association,

preacademic skills, and speech and language (Table 1). Administration and scoring of some items were simplified to increase interrater reliability and shorten

testing time.

Evaluation of DIALS According to

Pre-Established Key Features

Zittel (1994) listed six criteria that adapted physical educators should use in the

selection of a preschool assessment instrument. Each will be discussed as it relates

to DIAL-3.

Purpose

Selection features are "Resource materials state: what the instrument is designed

to provide; how the measurements can be used; the type of reference" (Zittel,

1994, p. 247).

What the Instrument is Designed to Provide. The DIAL-3 Manual states

that DIAL3 is an individually administered screening test designed to identify

young children in need of further diagnostic assessment. DIAL-3 is a 30-min

assessment of motoric, conceptual, and language behaviors. The DIAL-3 Parent

Questionnaire, completed during screening by a parent or caregiver, provides

normed scores for the child's self-help and social skills. The child's psychosocial

behaviors also are assessed by means of a rating scale completed by the testers in

the three performance areas (Motor, Concepts, and Language; Mardell-Czudnowski

& Goldenberg, 1998).

How the Measurements Can be Used. The results of DIAL-R screening

may be communicated to the parent(s) during a conference immediately after the

testing process or at a later time. These results will allow the coordinator to make

Table 1 DIAL3 Motor Area Illustrating the Abilities Assessed by the Items

DIAL-3

items

Motor area

Catching

Jump, hop, & skip

Building

Thumbs & fingers

Cutting

Copying

Writing name

VisualPrevious

motor

Short-term learning

integration memory association

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg (1998, p. 15).

Speech &

language

*

*

Preacademic

skills

*

*

86

Mardell-Czudnowskiand Goldenberg

one of the following statements about the child: (a) The child's development appears to be delayed when compared with those of the same age group, and further

assessment is recommended; or (b) The child appears to be developing in a satisfactory manner, and no serious difficulty is foreseen (Mardell-Czudnowski &

Goldenberg, 1998).

The Type of Reference. Although items were operationalized on the basis

of skills that kindergarten and first-grade teachers indicated were essential for success in school (criterion-referenced), DIAL, DIAL-R, and DIAL-3 have always

been standardized tests (norm-referenced).This means that each child is evaluated

in terms of other children's performances. For this comparison to be meaningful,

the norms must be adequate, which is dependent on three factors: the representativeness of the norm sample (age, gender, ethnicity, etc.), the size of the norm

sample, and the relevance of the norms in terms of the purpose of testing (Salvia &

Ysseldyke, 1998). In the case of DIAL-3, the purpose is screening. All of this

information is available in depth in the DIAL-3 manual (Mardell-Czudnowski &

Goldenberg, 1998) but is described briefly in the following sections.

Technical Adequacy

"Evidence for validity; evidence for reliability; standardized population" (Zittel,

1994, p. 247).

Evidence for Validity. According to the DIAL-3 Manual, "The validity of

a test is defined as the degree to which it accomplishes what it is designed to do"

(Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998, p. 82). Anastasi and Urbina (1997)

observe that construct validity has come to be recognized as the fundamental and

all-inclusive validity concept. DIAL-3 is based on the accurate measurement of

motor, concepts, language, self-help, and psychosocial skill development in young

children. Each DIAL-3 task had to demonstrate a consistent developmental growth

pattern across the age groupings of the DIAL-3 in order to be included in the final

20 items. Age differentiation is a major criterion used to validate developmental

tests, even though the existence of progressive increases in test scores with increased age does not guarantee that the test is measuring development.

Content and criterion-related validity provide valuable information in their

own right on the definition and understanding of the constructs measured by a test.

A number of concurrent and discriminant validity studies were conducted with

other screening and diagnostic tests. The results comparing DIAL-3 with two tests

(one screening and one diagnostic test) that have motor components are reported

here.

A total of 166 children from the DIAL-3 standardization sample were also

given the DIAL-R. The children were divided into two groups on the basis of age.

One group consisted of 88 children aged 3.5 to 4.5 (mean age 48.4 months, SD

3.2) and an older group of 78 children aged 4.6 to 5.4 (mean age 58.4 months, SD

3.2). Test administration was counterbalanced: Some children took the DIAL-R

before taking the DIAL-3, and others took the DIAL-3 first. The interval between

tests ranged from 13 to 77 days, with a mean interval of 38 days. Results are

presented in Table 2. Because of some sampling fluctuation in the standard deviations of the DIAL-3 scores (this affects the values of correlation coefficients), all

obtained correlations were corrected assuming a population standard deviation of

15 standard score points (Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998).

Preschool Motor Development

87

Table 2 Correlations of Motor and Total Scores on the DIAL-3 With DIAL-R

and DAS

DIAL3 Motor

r

Con."

Age

3.5 to 4.5

DIAL-R

Motor

Total

DIAL3

Mean

SD

4.6 to 5.4

DIAL-R

Motor

Total

DIAL-3

Mean

SD

DAS subtests

Copying

Nonverbal cluster

GCA

DIAL-3

Mean

SD

DIAL3 Total

r

Corr."

DIAL-R

SD

Mean

DAS

Mean

46.4

97.3

98.3

SD

9.8

15.2

13.8

=Allcoefficients were corrected for the variability of the norm group (SD = IS), based on

the standard deviation obtained on DIAL-3, using Guilford's (1954, p. 392) formula.

From Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg (1998, pp. 84, 88).

The DIAL-3 Total score has a moderately high corrected correlation with the DIALR Total score (0.91 for the younger sample and 0.84 for the older sample). In

addition, the DIAL-3 Motor scores correlate moderately well with the DIAL-R

Motor scores for both age groups (0.72 for the younger sample and 0.74 for the

older sample). These results provide good support for the convergent and discriminant validity of the DIAL-3 scores.

Fifty children from the DIAL-3 standardization sample also were given the

Differential Ability Scales (DAS; Elliott, 1990), which is a diagnostic test. They

covered an age range of 3.7 through 5.10 (mean age 4.7). They were given the

DAS and the DIAL-3 in counterbalanced order, with the interval between tests

varying from 1 to 72 days (mean interval 11 days). Table 2 shows the correlations

between the DIAL-3 motor and total scores and the DAS motor measures and

DAS General Conceptual Ability (GCA) score, which is the overall composite.

88

Mardell-Czudnowski and Goldenberg

The DIAL-3 Total correlates substantially (0.79) with the DAS overall composite

score (GCA). The DIAL-3 Motor score has a corrected correlation of 0.51 with

DAS Copying (a task included in the DIAL3 Motor area). Motor also correlates

substantially (0.62) with DAS Matching Letter-Like Forms, which is a nonverbal

subtest, and with the Nonverbal Cluster score (0.51). These results show strong

relationships between DIAL-3 and the DAS and support the validity of the DIAL-3.

Although it is not one of the categories of technical validity, Anastasi (1988)

states that face validity is considered essential to obtain cooperation from participants and to instill acceptance in the minds of test users. Face validity is a first

impression of whether a test appears to be measuring the intended content in an

appropriate manner. For instance, a screening test for young children should be

gamelike and appealing. Young children have no concept of the meaning of "taking a test," so their typical performance has to be elicited in other ways. DIAL-3

includes a variety of appealing tasks, novel materials, colorful pictures, age-appropriate manipulatives, and carefully controlled entry and exit requirements, which

all contribute to maximizing the child's cooperation and interest. Increased interest and cooperation, in turn, contribute to the validity of the obtained scores

(Mardell- Czudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998).

Evidence for Reliability. The concept of reliability concerns the accuracy

or consistency of scores. Two types of reliability are internal consistency based on

inconsistencies in a person's responses to individual items in the test and testretest reliability based on the inconsistencies due to fluctuations in performance

over time. The median alpha (internal) reliability of the DIAL-3 Total score is

0.87, based on the standardization sample of 1,560 children. Motor area alpha

reliabilities range from 0.45 to 0.74. The median of 0.66 is brought down by the

older children (ages 6-6 to 6-11) because a number of children of this age obtain

near-maximum scores. As expected, area scores demonstrate somewhat lower internal reliability, primarily because area scores are based on fewer items than is the

DIAL-3 Total score. The DIAL-3 Total scores have adequate reliability at every 6month age span (but the above mentioned one) for screening purposes, according

to Salvia and Ysseldyke's (1998) standard of 0.80 for a screening test.

To measure test-retest reliability, DIAL-3 was administered twice to 158

children (86 boys and 72 girls) from the standardization sample, who were divided

into two groups on the basis of age. One group consisted of 80 children aged 3.6 to

4.5 (M = 47.4 months, SD = 3.5) and an older group of 78 children aged 4.6 to 5.10

(M = 60.4 months, SD = 3.6). The interval between tests ranged from 12 to 65 days

(M = 28 days). The DIAL-3 Total scores (0.88 and 0.84 for the two groups) have

very satisfactory test-retest reliabilities that are above the Salvia and Ysseldyke

(1998) criterion of 0.80 for a screening test. The DIAL-3 Motor area reliabilities

(0.69 and 0.67) cluster around 0.70, indicating that the Motor area should not be

used as a separate test but only as part of the total screening (Mardell- Czudnowski

& Goldenberg, 1998).

Standardized Population. DIAL-3 was normed on a national sample of

1,560 English-speaking and 650 Spanish- speaking children, stratified by chronological age, gender, geographic area, race or ethnic group, and parent education

level. As the sampling plan was completed, its correspondence to the population

target figures was tracked at the level of joint frequencies of the stratification variables. Therefore, the sample was matched to the population not only for one demographic variable at a time but also for combined variables (Mardell-Czudnowski

& Goldenberg, 1998).

Preschool Motor Development

89

Nondiscriminatory

"Adaptations permitted, multisource information permitted, standardized sample

sensitive to culture and disability" (Zittel, 1994, p. 247).

Adaptations Permitted. Any adaptations are permitted as long as they do

not interfere with the standardized manner in which the test is to be administered.

For example, children would have to be ambulatory to participate in the two gross

motor items, but if not, they could still participate in the five fine motor items.

Multisource Znfomzation Permitted. DIAL-3 is designed not only to permit multisource information but to require it. Each area is administered by a different adult so that the child is screened by a minimum of three adults. Along with the

abilities and behaviors that are evaluated by the screening team, the DIAL-3 includes the parent questionnaire, which concentrates on the child's self-help and

social development. It provides normed scores for the child's self-help and social

skills which, combined with the behavioral ratings from the DIAL-3 operators,

provide the basis for the need of further assessment in the psychosocial area. The

parent questionnaire also requests other information that should be shared between

parents and professionals, such as medical history, family background, and general development. Information received from parents, who see the child in his or

her natural environment, adds to the social and ecological validity of the screening

in ways that standardized assessments cannot match (Mardell-Czudnowski &

Goldenberg, 1998).

Standardized Sample Sensitive to Culture and Disability. Both the DIAL3 and the Speed DIAL, a shortened version administered by one person rather than

a team, may be administered in English or Spanish. The Spanish version is not

merely a translation of DIAL-3 but a test that has been normed on a national sample

of young Spanish-speaking children. Great care was taken to make sure DIAL3

measures accurately in English or Spanish. The goal was to keep the two versions

as similar as possible.

Children with special educational needs comprised approximately 10% of

the total sample. A total of 161 children in the standardization sample were reported as receiving special education services. These 161 children received 292

services. They were categorizedinto the following groupings: physical, cognitive,

communication, social or emotional, and adaptive.

Administrative Ease

"Scoring more than passlfail; interpretation includes a raw score summary, comments related to performance, or level of mastery indicated; administration time

clearly stated or flexibility in test component administration allowed" (Zittel, 1994,

p. 247).

Scoring More Than Pass/Fail. Every item is scored by objective criteria

on the record form. The raw score is easily converted to a 5-point scaled score.

Then the scaled scores are added within each area and the three areas are combined for a DIAL-R total score. A computer software program is available to assist

in making this process very accurate and fast. It also contains a summary for parents and parent-child activities (both in English or Spanish) that are gamelike yet

educationally sound.

Interpretation includes a raw score summary, comments related to peiformance, or level of mastery indicated. The record form allows examiners to know

90

Mardell-Czudnowskiand Goldenberg

exactly what the child could do by looking at one page for each area that contains

all of the tasks. The scaled score indicates a rough measure of mastery according

to age. The final decision is based on a number of factors selected by each screening site (e.g., the percentage of children the site wants to identify).

Administration Time Clearly Stated or Flexibility in Test Component Administration Allowed. With one exception in the Concepts area, DIAL-3 items

and tasks are not timed; children are allowed to take as much time as they need to

respond. However, it is the responsibility of the operator to present the materials in

such a way that children know what is expected and want to respond. This is accomplished through a training workshop that introduces operators to the DIAL-3

screening procedures. The DIAL-3 kit contains a reusable training packet that contains written tests, answers for the written tests, performance tests, and scripts for

roleplaying. The DIAL-3 training videotape demonstrates the administration of all

items in each area besides showing the overall screening situation (MardellCzudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998).

Instructional Link

"Curriculum-referenced,test items sequenced to provide low inference for instructional objectives, ability to monitor progress" (Zittel, 1994, p. 247).

Curriculum-Referenced. Guidelines have been developed by a national task

force on screening and assessment for the National Center for Clinical Infant Programs. One of the ten guidelines states "Processes, procedures, and instruments

intended for screening should only be used for their specified purposes7'(1989, p.

24). The specific purpose of DIAL3 is to identify children with current or potential learning problems. Thus, we do not believe that a screening test should have an

instructional link nor be used to determine cumculum. However, it is easy to see,

using the record form, exactly which skills are age appropriate and which ones

require instructional links. Additionally, parent and child activity forms that are

identical in content to the ones in the computer program suggest general activities

that parents may use to enhance their child's overall development in each of the

five areas. Hence, there are suggestions for motor activities. The activities presented require minimal commercial materials and can be accomplished in a short

period of time (Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998).

Test Items Are Sequenced to Provide Low Inference for Instructional

Objectives. Since DIAL-3 was normed on 1,560English-speakingand 605 Spanish-speaking children stratified by age, tasks within each test item have been sequenced according to difficulty level to allow for appropriate age level entrance

and exit points. This also assists in the development of instructional objectives

based on substantive data of what children are typically capable of doing at given

ages.

Ability to monitorprogress. As a screening test, DIAL3 was not designed

to monitor progress. However, retesting over a 6-month or 12-month period does

show the child's progress (Mardell-Czudnowski, Goldenberg, Suen, &Fries, 1988).

Ecological Validity

"Familiar materials, familiar setting, caregiver present" (Zittel, 1994, p.247).

Familiar Materials. While DIAL-3 does employ familiar materials (e.g.,

red and white blocks, scissors, primary pencil) in the motor area, it also uses novel

Preschool Motor Development

91

materials (e.g., red apple beanbag, cutting cards, Copying Dial) to interest the

child in a new activity.

Familiar Setting. DIAL-3 screening is often conducted in the child's school

or childcare center. However, allowance is made for the occasion when the child is

screened in an unfamiliar setting. All children are allowed to sit (and play) at a

play table for as long as necessary before going to any of the three areas to be

screened. This is another unique feature of DIAL tests.

Caregiver Present. All screening is done in the presence of the caregiver.

A part of the screening room is set aside for caregivers and younger siblings. If

necessary, the caregiver may even accompany the child to the screening area.

Summary

Developing a nationally standardized screening test is both time consuming and

costly. This article briefly describes the previous versions of DIAL and DIAL-R

and the development of new and revised items in the motor area for DIAL-3. The

same procedures were followed for the development of items in the other four

sections of the test: concepts, language, self-help, and psychosocial. Then DIAL3 is evaluated using the key features for selecting an appropriate preschool gross

motor assessment instrument (Zittel, 1994).

The quest for the most predictive preschool screening test will continue until

educators and caregivers, working together, can accurately identify all children

whose developmental delay or differences suggest the need of special educational

services and then provide such services within and outside of the early childhood

setting. It is important that adapted physical educators, as members of the screening team, be aware of the latest screening tests and how they meet the criteria

established for evaluating all of the components of the test.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (n.d.). Developmental landmarks.Washington, DC: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Anastasi, A. (1988). Psychological testing (6th ed.). New York: Macmillan.

Anastasi, A,, & Urbina, S. (1997). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Banham, K. (1963).Quick screening sc& u~mentaldevelopment. Murfreesboro, TN: Psychometric Affiliates.

Barsch, R., & Rudell, R. (1962). A study of reading development among 77 children with

cerebral palsy. Cerebral Palsy Review, 23,3-13.

Bayley, N. (1968).Bayley scales of infant development. New York: PsychologicalCorporation.

Beery, K. (1982).Revised administration, scoring, and teaching manual for the Developmental Test of Wsual-MotorIntegration. Cleveland, OH: Modem Curriculum Press.

Bredekamp, S., & Copple (Eds.) (1997). Developmentally appropriate practices in early

childhoodprograms serving childrenfrom birth to age 8. Washington, DC: National

Association for the Education of Young Children.

Bryant, N. (1964).Some conclusionsconcerning impaired motor development among reading

disability cases. Bulletin of Orton Society, 14, 16-17.

92

Mardell-Czudnowski and Goldenberg

Campbell, S. (1985). Assessment of the child with CNS dysfunction. In J. Rothstein, (Ed.),

Measurement in physical therapy (pp. 207-228). New York: Churchill Livingstone.

Case, R. (1985). Intellectual development: Birth to adult. London: Academic Press.

Cattell, P. (1960). Measurement of intelligence of infants and young children. New York:

Johnson Reprint Corp.

Cratty, B. (1967). Movement behavior and motor learning (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lea &

Febiger.

Current population survey (March, 1994) [Machine-readable data file]. Washington, DC:

Bureau of the Census (Producer and Distributor).

Doll, E. (1935). Vineland social maturity scale. Circle Pines, M N : American Guidance

Service.

Doll, E. (1966). Preschool attainment record. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Dunsing, J., & Kephart, N. (1965). Motor generalization in space and time. Learning disorders (Vol. 1). Seattle, WA: Special Publications.

Elliott, C.D. (1990). DAS administration and scoring manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Fawcett, A., & Nicolson, R. (1995). Persistent deficits in motor skill of children with dyslexia. Journal of Motor Behavior, 27,235-240.

Federal Register. (1997). PL 105-17. Individuals with disabilities education act.

Fletcher, J., & Satz, P. (1982). Kindergarten prediction of reading achievement: A seven

year longitudinal follow-up. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 42,681685.

Fowler, M., & Cross, A. (1986). Preschool risk factors as predictors of early school performance. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 7(4), 237-241.

Frankenburg, W., & Dodds, J. (1968).Denver developmental screening test. Denver: Ladoca

Publishing Foundation.

Gesell,A. (1952). Infant development: The embryology of early human behavior. New York:

Harper.

Gesell, A., & Amatruda, E. (1947). Developmental diagnosis (2nd ed.). New York: HoeberHarper.

Gesell, A., & Thompson, H. (1938). The psychology of early growth including norms of

infant behavior and a method of genetic analysis. New York: Macmillan.

Goodenough,F., Maurer, K., &Van Wagenen, M. (1940). Minnesota Preschool Scale. Circle

Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Gredler, G. (1992). School readiness: Assessment and educational issues. Brandon, VT:

Clinical Psychology Publishing.

Gredler, G. (1997). Issues in early childhood screening and assessment. Psychology in the

Schools, 34(2), 99-105.

Guilford, J. P. (1954). Psychometric methods (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hall, J., Mardell, C., Wick, J., & Goldenberg, D. (1976). Further development and refinement of DIAL, final report. Resources in Education (ED 117 200).

Hrncir, E., & Eisenhart, C. (1991). Use with caution: The "at-risk" label. Young Children,

46, 23-27.

Huttenlocher, P., Levine, S., Huttenlocher, J., & Gates, J. (1990). Discrimination of normal

and at-risk preschool children on the basis of neurological tests. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 32,394-402.

Hynd, G., & Willis, W.G. (1988). Pediatric neuropsychology. Orlando: Grune & Stratton.

Johnson, D., & Myklebust, H. (1967). Learning disabilities, education principles andpractices. New York: Grune & Stratton.

Preschool Motor Development

93

Karlin, R. (1957). Physical growth and success in undertaking beginning reading. Journal

of Educational Research, 51, 191-201.

Keogh, B., & Speece, D. (1996). Learning disabilities within the context of school. In D.

Speece & B. Keough (Eds.), Research on classroom ecologies: Implications for inclusion of children with learning disabilities (pp. 1-14). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kephart, N. (1960). The slow learner in the classroom. Columbus, OH: Charles Merrill.

Kuhlman, F. (1939). Tests of mental development. Minneapolis: Educational Test Bureau.

Mardell, C., & Goldenberg, D. (1972). Learning disabilities/earlychildhood researchproject.

Springfield, E: Ofice of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, State of Illinois.

Mardell, C., & Goldenberg, D. (1973). Instruments for screening of prekindergarten children. Research in education, (ERIC No. ED 082 408).

Mardell, C., & Goldenberg, D. (1975). Developmental indicators for the assessment of

learning (DIAL). Edison, NJ: Childcraft Educational Corporation.

Mardell-Czudnowski, C. (1980). Validity and reliability studies with DIAL. Journal for

Special Educators, 17(1), 32-45.

Mardell-Czudnowski, C., & Goldenberg, D. (1983). Developmental indicatorsfor the assessment of leaming-revised (DIAL-R). Edison, NJ: Childcraft Educational Corporation.

Mardell- Czudnowski, C., Goldenberg, D., Suen, H., &Fries, R. (1988). Predictive validity

of DIAL-R. Diagnostique, 14(1), 55-62.

Mardell-Czudnowski, C., & Goldenberg, D. (1990). Developmental indicators for the assessment of learning-revised, American Guidance Service edition. Circle Pines, MN:

American Guidance Service.

Mardell-Czudnowski, C., & Goldenberg, D. (1998). Developmental indicators for the assessment of learning-third edition (DIAL-3). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance

Service.

McGraw, M. (1943). The neuromuscular maturation of the human irzfant. New York: Columbia University Press.

McLean, M., Smith, B., McConnick, K., Shakel, J., & McEvoy, M. (1991). Developmental

delay: Establishing parameters for a preschool category of exceptionality. Position

paper for Division for Early Childhood, Council for Exceptional Children.

National Center for Clinical Programs (1989). Screening and assessment: Guidelines for

identiJfving young disabled and developmentally vulnerable children and theirfamilies. Washington, DC: Author.

NEC*TAS (1992). Section 619 profile: A profile of Part B section 619 services. Chapel

Hill, NC: National Early Childhood Technical Assistance System, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Salvia, J., & Ysseldyke, J. (1998). Assessment (8th ed.) Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Simner, M. (1989). Predictive validity of an abbreviated version of the Printing Performance School Readiness Test. Joumal of School Psychology, 27,2, 189-195.

Simner, M. (1994). Improving the predictive validity of geometric-design copying tasks on

instruments used to evaluate school readiness. In C. Faure, ,P. Keuss, G. Lorsette, &

A.Vinter, (Eds.) Advances in handwriting and drawing: A multidisciplinary approach

(pp. 489-500). Paris: Europia.

Smith, C. (1991). Learning disabilities: The integration of learnel; task and setting. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Stutsman, R. (1926-48). Merrill Palmer scale of mental tests. Wood Dale, L: Stoelting.

Sulzby, E. (1990). Assessment of emergent writing and children's language while writing.

In L. Morrow & J. Smith (Eds.), Assessment for Instruction in Early Literacy (pp.

83-109). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

94

Mardell-Czudnowski and Goldenberg

Terman, L., & Menill, M. (1960). Stanford-Binet intelligence scale. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin.

Welsh, M., Pennington, B., & Groisser, D. (1991). Anonnative study of executive function:

A window on prefrontal function in children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 7,

131-149.

Wright, B. & Masters, G. (1982). Rating Scale Analysis: Rasch Measurement. Chicago:

Mesa Press.

Zittel, L. (1994). Gross motor assessment of preschool children with special needs: Instrument considerations.Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 11,245-260.

Authors' Notes

The authors wish to thank the entire staff at American Guidance Service

(AGS), the publishers of DIAL-R and DIAL-3, who were instrumental in the

item development of DIAL-3. In particular, we are most grateful to Colin Elliott,

Shelly Saunders, Lora Oberle, J.J. Wang and Tsuey- Hwa Chen at AGS. More

information about ordering DIAL-3 may be obtained from AGS. Tel: (800) 3282560; Fax: (612) 786-9077; E-mail: <agsmail@agsnet.com>.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Carol

Mardell-Czudnowski, 1605-B Pacific Rim Court, PMB 7 1-429143905, San

Diego, CA 92143-9015 <carolnmoshe@laguna.com.mx>; Dorothea Goldenberg,

Dial Inc., PO Box 911, Highland Park, IL 60035.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- BarackObama AstrolabesProfessionalNatalReport LV PDFDokument25 SeitenBarackObama AstrolabesProfessionalNatalReport LV PDFmadtur77Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jeff Spiegel, The Kabbalah Manual PDFDokument373 SeitenJeff Spiegel, The Kabbalah Manual PDFmadtur770% (1)

- Wisc IVDokument13 SeitenWisc IVmadtur77Noch keine Bewertungen

- Astrologia Curso Calendario MayaDokument26 SeitenAstrologia Curso Calendario Mayamadtur77100% (1)

- 2014 SelectedproblemsDokument36 Seiten2014 Selectedproblemsmadtur77Noch keine Bewertungen

- Eileen Nauman-Medical AstrologyDokument363 SeitenEileen Nauman-Medical Astrologyapollinia54100% (8)

- KBIT2 Despre PDFDokument13 SeitenKBIT2 Despre PDFmadtur77100% (1)

- Bisuteria Con Crochet - Bead & Button 10 ProjectsDokument20 SeitenBisuteria Con Crochet - Bead & Button 10 Projectsmadtur7784% (19)

- Sun Tzu Art WarDokument398 SeitenSun Tzu Art Wartranngan100% (11)

- US Marine Corps - MWTC Wilderness Medicine CourseDokument375 SeitenUS Marine Corps - MWTC Wilderness Medicine Courseasnar100% (1)

- AtlantisDokument226 SeitenAtlantisRodney Mackay100% (9)

- Crochet PatternsDokument58 SeitenCrochet Patternskeerthinick100% (15)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Gradual Release of Responsibility ModelDokument9 SeitenThe Gradual Release of Responsibility Modeljohn sommerfeldNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20 06 Feb Newsletter 2011 12 FinalDokument8 Seiten20 06 Feb Newsletter 2011 12 FinalChirag PatwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 Audit-1 Course OutlineDokument5 Seiten2019 Audit-1 Course OutlineGeraldo MejillanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pedagogical Principles in Teaching Songs and PoetryDokument15 SeitenPedagogical Principles in Teaching Songs and PoetryAmirahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Lecture Assignment: National Service Training Program 101 Course Orientation Session 1 August 13, 2021Dokument7 SeitenPre-Lecture Assignment: National Service Training Program 101 Course Orientation Session 1 August 13, 2021James LorestoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research PaperDokument18 SeitenResearch PaperBhon RecoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bullying Power PointDokument24 SeitenBullying Power PointJessica PagayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course Outline Physics EducationDokument3 SeitenCourse Outline Physics EducationTrisna HawuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0620 s14 QP 61Dokument12 Seiten0620 s14 QP 61Michael HudsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Be A Professional TeacherDokument27 SeitenHow To Be A Professional TeacherVisali VijayarajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Improving Students Speaking Skills Through English SongDokument8 SeitenImproving Students Speaking Skills Through English SongnindyaarrrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humanism PDFDokument7 SeitenHumanism PDFGiacomo FigaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- DCC Session 2Dokument2 SeitenDCC Session 2Googool YNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cap College NewDokument10 SeitenCap College NewAbby Joy FlavianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alyssa Mcmahon Evidence Chart 2023Dokument8 SeitenAlyssa Mcmahon Evidence Chart 2023api-565563202Noch keine Bewertungen

- Duke Orgo 201Dokument5 SeitenDuke Orgo 201CNoch keine Bewertungen

- 419 - 07 Adrian BRUNELLODokument6 Seiten419 - 07 Adrian BRUNELLOAzek NonovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Studies Posterboards Native American ProjectDokument5 SeitenSocial Studies Posterboards Native American Projectapi-254658342Noch keine Bewertungen

- Action Plan in MTB MleDokument4 SeitenAction Plan in MTB MleCharisse Braña100% (2)

- Special Education Citizen Complaint (Secc) No. 13-72 Procedural HistoryDokument21 SeitenSpecial Education Citizen Complaint (Secc) No. 13-72 Procedural HistoryDebra KolrudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action PlanDokument4 SeitenAction PlanBeth AjoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why College & MajorDokument29 SeitenWhy College & MajorbmegamenNoch keine Bewertungen

- SLM - Ro - Mil-Q2 Module 12Dokument20 SeitenSLM - Ro - Mil-Q2 Module 12Bill Villon90% (10)

- Lesson Planning-Teaching PracticeDokument11 SeitenLesson Planning-Teaching PracticeRamatoulaye TouréNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law On Negotiable Instruments Law SyllabusDokument2 SeitenLaw On Negotiable Instruments Law SyllabusThea FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Efficacy of Stuttering Therapies - PDF /KUNNAMPALLIL GEJODokument24 SeitenEfficacy of Stuttering Therapies - PDF /KUNNAMPALLIL GEJOKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biology 2, July 3, 2019Dokument2 SeitenBiology 2, July 3, 2019Lagoy Zyra MaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- AF - Aquaculture NC II 20151119Dokument28 SeitenAF - Aquaculture NC II 20151119Michael ParejaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kindergarten Assessment ToolDokument55 SeitenKindergarten Assessment ToolMi Young Kim67% (3)

- Chapter IDokument16 SeitenChapter Iiyai_coolNoch keine Bewertungen