Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Daily Emotional States As Reported by Childrens and Adolescents.

Hochgeladen von

albervaleraOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Daily Emotional States As Reported by Childrens and Adolescents.

Hochgeladen von

albervaleraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Daily Emotional States as Reported by Children and Adolescents

Author(s): Reed Larson and Claudia Lampman-Petraitis

Source: Child Development, Vol. 60, No. 5 (Oct., 1989), pp. 1250-1260

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Society for Research in Child Development

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1130798 .

Accessed: 07/04/2014 07:13

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and Society for Research in Child Development are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Child Development.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Daily Emotional States as Reported by Children

and Adolescents

Reed Larson

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaignand Michael Reese Hospital

Claudia Lampman-Petraitis

Loyola University of Chicago

LARSON, REED, and LAMPMAN-PETRAITIS,CLAUDIA.Daily Emotional States as Reported by Children and Adolescents. CHILDDEVELOPMENT,

1989, 60, 1250-1260. Hour-to-houremotional states

reportedby children, ages 9-15, were examined in orderto evaluatethe hypothesis thatthe onset of

adolescence is associated with increased emotional variability.These youths carried electronic

pagers for 1 week and filled out reportson their emotional states in response to signals received at

randomtimes. To evaluate possible age-relatedresponse sets, a subset of children was asked to use

the same scales to rate the emotions shown in drawingsof 6 faces. The expected relationbetween

daily emotional variabilityand age was not found among the boys and was small among the girls.

There was, however, a linear relationbetween age and averagemood states,with the older participants reportingmore dysphoricaverage states, especially more mildly negative states. An absence

of age difference in the ratingsof the faces indicatedthat this relationcould not be attributedto age

differences in response set. Thus, these findings provide little supportfor the hypothesis that the

onset of adolescence is associatedwith increased emotionalitybut indicate significantalterationsin

everyday experience associated with this age period.

Adolescence has long been characterized

as a time of increased emotionality. Aristotle

described youth as "passionate, irascible, and

apt to be carried away by their impulses"

(cited by Fox, 1977). G. Stanley Hall wrote

that it is adolescents' "natural impulse to experience hot and perfervid states" (1904, Vol.

2, pp. 74-75). Similar descriptions of adolescent moodiness or emotionality have been

formulated by social psychologists (Becker,

1964; Lewin, 1938), anthropologists (Benedict, 1938; Mead, 1928), psychoanalysts (Blos,

1961; Freud, 1937), novelists (Spacks, 1981),

and professionals concerned with junior and

senior high school education (Eichhorn,

1980). Laypersons interviewed by Hess and

Goldblatt (1957) and Musgrove (1963) also

used such words as "impulsive," "unstable,"

and "wild" to describe the "average teenager." The underlying hypothesis is that adolescents, perhaps because of the physiological, psychological, and social changes of this

age period, experience emotional states that

are more extreme, change more quickly, and

are less predictable than those experienced at

earlier or later periods.

To evaluate the hypothesis that adolescents are more emotionally variable than

preadolescents, we examined time-sampling

reports obtained from 9-15-year-olds concerning the emotional states they experienced

during their daily lives. The vantage point for

this investigation was phenomenological; we

were concerned with the hour-to-hour range

of emotional states children and adolescents

attribute to themselves-with

their "conscious states" (Harris & Olthof, 1982)acknowledging that a different pattern of

findings might emerge were it possible to

measure components of emotion that a person

does not consciously detect, such as physiological arousal or unconscious affect. Emotional variability was defined for this study as

the standard deviation of a person's daily

mood states as assessed on a continuum from

positive to negative states. The research question is, then, do adolescents experience a

wider range of emotional states than preadolescents? In their daily lives do they attribute

to themselves the greater variation in states

that have long been attributed to them by observers? The study also addresses the related

This research was supported by NIMH grant 1 R01 MH38324, "Stressin Daily Life during

Early Adolescence," awardedto Reed Larsonand carriedout throughMichael Reese Hospital and

Medical Center. Send requests for reprintsto the first authorat the Division of Human Development and Family Ecology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,1105 West Nevada Street,

Urbana, IL 61801.

[Child Development, 1989, 60, 1250-1260. ? 1989 by the Society for Researchin Child Development, Inc.

All rightsreserved.0009-3920/89/6005-0008$01.00]

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Larson and Lampman-Petraitis

question of whether they experience

emotional extremes.

more

BackgroundResearch

One must separate the hypothesis of adolescent emotionality from the broader hypothesis that adolescence is a time of turmoil or

"storm and stress," a view that no longer enjoys general acceptance (Adelsen, 1979; Petersen, 1988; Strober, 1986). The turmoil hypothesis asserts that emotionality is part of

a normal and even desirable adolescent condition of personality disruption and change

(Blos, 1961; Freud, 1937). Research findings,

however, make it clear that such disruption is

neither normative nor desirable. The great

majority of adolescents report feeling globally

happy with their lives (Offer, Ostrov, & Howard, 1981), rates of psychiatric disorder during

adolescence are not greater than at later periods of the life span (Rutter, Graham, Chadwick, & Yule, 1976), and the typical teenager

does not experience a breach in relations with

parents (Hill & Holmbeck, 1986; Montemayor, 1986). Furthermore, when turmoil

does occur, it is associated with worse, not

better long-term adjustment (Dusek & Flaherty, 1981; Kohlberg, LaCrosse, & Ricks,

1974; Offer & Offer, 1975).

The absence of a general condition of turmoil among a majority of teenagers, however,

does not disprove the more specific hypothesis that adolescents are emotional creatures.

The possibility remains that wide emotional

extreme positive as well

swings-including

as negative emotional states (Sharp, 1980)are a normative part of the adolescent experience.

Research provides some indication that

adolescents experience stronger emotions in

their daily lives than do adults. Direct data on

daily emotional experience were obtained by

Larson, Csikszentmihalyi, and Graef (1980),

who used electronic pagers to signal adolescents and adults to report on their subjective

experiences at random times during the day.

They found that the mood states reported by a

sample of high school students had higher

standard deviations than those reported by a

sample of adults. The mean mood levels reported by the two groups were similar, indicating that their emotional states had similar

baselines; the adolescents, however, reported

more occasions both of negative and positive

extremes.

Additional evidence comes from onetime questionnaire studies showing that

youth and young adults report greater emotional extremes than older adults. Sixteen- to

1251

19-year-olds studied by Diener, Sandvik, and

Larsen (1985) obtained higher scores on "affective intensity" than older members of the

same families. Bradburn (1969) and Campbell

(1981) found more frequent reporting of both

positive and negative affect among young

adult survey respondents than among successive groups of older respondents. A set of projective studies reviewed by Malatesta (1981)

also suggests a reduction in affective extremes

from youth to old age, although the author

suggested methodological reasons for avoiding this conclusion and in a questionnaire

study such an age trend was not evidenced

(Malatesta & Kalnok, 1984).

These studies provide initial confirmation for the hypothesis that adolescence is a

period of emotional variability. Their findings, however, are subject to two major limitations. First, while distinguishing the daily

pattern of adolescent emotional states from

that of adults, adolescents' states were not

studied in relation to those of children. It is

possible that emotionality in adolescence is

merely a continuation of childhood lability.

Indeed, infants and children also have a reputation for being emotionally variable (Malmquist, 1975; Weiner & Graham, 1984).

A second problem lies in the possibility

that the results reflect age changes in how

people use self-report mood scales. Research

on response styles indicates that, with age,

children and adolescents use less extreme

scale points in rating ambiguous stimuli.

Light, Zax, and Gardiner (1965), for example,

found less use of response extremes in ratings

of neutral stimuli from the fourth to eighth to

twelfth grades (see also Hamilton, 1965).

Thus, it is conceivable that differences found

between adolescents and adults may reflect

nothing more than a change in response style.

In other words, adults may experience the

same emotional states as adolescents, butowing to their greater base of experiencereport these states as less extreme.

Both of these problems can be resolved

by comparing the emotional variability of adolescents with children. If emotionality is a

distinguishing trait of adolescents-not just a

continuation of a childhood condition-then

adolescents should report wider daily emotional variations than children. But if age

differences in response style influence selfreport data, then children, rather than adolescents, should report greater emotional extremes.

In this study, therefore, we compared the

range of emotional states experienced by chil-

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1252

Child Development

dren and adolescents. The onset of adolescence in the United States, where the study

was done, is typically associated with pubescence, the start of junior high school, and

other transitions that occur between the sixth

and ninth grades (Lipsitz, 1977; Steinberg,

1985). In order to obtain an adequate representation of preadolescents, we included fifth

graders; hence our sample includes students

from the fifth to the ninth grades (ages 9 to

15). The emotionality hypothesis predicts an

increase in the statistical variance of hour-tohour mood states across this age period. We

also examined age differences in average

states and the frequency of extreme states.

Following the procedure used by Larson

et al. (1980) these students rated their moods

at random times during the day in response to

signals from a pager. In order to discriminate

findings from trends that might be attributed

to response style, we also asked a subsample

of the students to rate the emotional states

they perceived in six simple drawings of faces

representing a range of emotions. Given the

quantity of evidence showing sex differences

during this age period, all analyses were performed separately for girls and boys.

Method

Subjects.-Participants in the study were

473 randomly selected children and young

adolescents in the fifth to ninth grades (ages 9

to 15) from four suburban neighborhoods in

the Midwestern United States. Two neighborhoods were generally lower middle class,

the third was middle class, and the fourth was

upper middle class. These communities were

composed almost exclusively of people with

European ancestry. To diversify possible

time-of-year effects and make the data collection manageable, the participation of the students was spread across eight waves of data

collection over 2 years. Sample selection was

stratified to obtain balanced representation by

sex, community, time of year, and grade, with

approximately equal numbers of students representing each quarter from the autumn of

fifth grade to the winter of ninth grade.

The final sample includes 68.8% of the

randomly selected students initially invited to

take part. Twenty-four percent of those invited declined to take part or failed to obtain

permission from their parents, 4.4% began the

study but failed to complete the requisite

number of self-report forms, and 2.8% completed the study but provided data that were

unusable. Sample loss was approximately

equal among boys and girls (32.2% vs. 30.2%,

respectively) and was more frequent in the

higher grades for boys (fifth to ninth: 24%,

23%, 33%, 42%, 37%; tau b = .13, p < .005)

but not for girls (tau b = -.01, N.S.). A survey of the entire school population in two of

the six schools (Larson, 1989) indicated that

the students who declined participation did

not differ in social class, as reflected by Hollingshead ratings of their parents' occupations

(Hollingshead & Redlich, 1958), or selfesteem, as measured by a six-item version of

the Rosenberg scale (Rosenberg, 1965). They

were more likely than participants to live

with a stepparent; however, separate analyses

showed little relation between parents' marital status and the properties of emotional

states considered here. Sociometric ratings

obtained in one school indicated no significant relation between nonparticipation and an

individual's popularity among peers. This

general absence of differences between participants and nonparticipants, particularly in

self-esteem, suggests that the higher sample

loss among the older boys does not introduce

sampling bias.

Separate analyses showed that the small

fraction of students who participated in the

study but were not included in the final sample (6.2% of those initially invited) were rated

as significantly less mature by their teachers,

received lower grades in school, and came

from families with significantly lower SES

characteristics. They also rated themselves as

slightly more depressed, with marginal significance, on a standard depression inventory

(Larson, 1989). However, since these 39 individuals were distributed across age and sex

categories, their exclusion does not create

bias in the final sample.

Procedures.-Following the procedures

of the Experience Sampling Method (ESM)

(Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1987; Hormuth,

1986; Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1983), participants carried electronic pagers for 1 week

along with a booklet of self-report forms.

Seven signals were sent to the pagers each

day between 7:30 A.M.and 9:30 P.M.,with one

signal at a random time within each 2-hour

block. The students' instructions were to

carry the pager with them at all times and to

fill out one self-report form immediately after

each signal was received. The pager could be

turned off if they took a nap, went to bed before 9:30 P.M.,or planned to sleep late. Otherwise the stated goal was to obtain descriptions of their experience at each of the

designated times.

The students together responded to a total of 17,752 of the ESM signals by filling out

self-report forms, an average of 37.5 per per-

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Larson and Lampman-Petraitis

son. After discounting signals that were

missed due to sleep and mechanical failure of

the pager, this represents a response to 84% of

the signals that were sent. Information obtained from the debriefing interview suggests

that the missed signals occurred during a

wide range of activities and do not represent

one particular category of experiences (Larson, 1989). The final sample of self-reports

thus provides a close-to-representative sample of their daily lives.

Instruments.-Students

rated their emotional states or moods at the time of each signal using six 7-point semantic-differential

scales. These items dealt with two basic dimensions of emotional experience that have

been identified and found to be stable for

children this age (Russell & Ridgeway, 1983).

Three of these items dealt with the dimension of pleasure-displeasure or affect (happyunhappy, cheerful-irritable, friendly-angry);

three dealt with the dimension of arousal

(alert-drowsy, strong-weak, excited-bored).

Values for these items are reported below on

a metric from - 3 to + 3, with negative values

corresponding to more dysphoric states, and

positive values corresponding to positive

states.

The analyses in this paper are based on

aggregated scores, computed for all of the

self-reports provided by each person. Hence

our unit of analysis is the person (N = 473),

not the individual time sample (N = 17,752).

The primary scores that were examined are

the standard deviation of each person's responses to each item-which serve as indices

of emotional variability-and

the means of

each person's responses to these itemswhich serve as indices of baseline emotional

state. The correlation matrix for these scores,

presented in Table 1, shows correlations

among the means ranging from r = .89 to .31

and correlations among the standard deviations ranging from r = .80 to .37. The correlations between the means and standard deviations range from r = .26 to -.30.

To evaluate the reliability of these scores,

the sequence of self-reports for each individual was divided at the middle point in the

week and the scores computed separately for

the first half of the person's week and the second half. The correlations between these

scores ranged from r = .57 to .46 for the standard deviations of the six items, and r = .73 to

.66 for the means (Larson, 1989). Given that

emotional states vary as a function of the ongoing events in people's lives, these values

are within an expected level of intra-subject

consistency. Findings demonstrating the va-

1253

lidity of these mood measures are presented

in an article by Csikszentmihalyi and Larson

(1987).

Evaluation of response style.-In order

to assess age differences in the tendency to

respond at the extremes on these scales, a

subset of 106 fifth to eighth graders from the

final two waves of the study were asked at the

end of the week of paging to use the same set

of semantic differential items to rate each of

six simple line drawings of faces. Ekman and

Friesen's (1975) guide to emotions in the human face was used to select features for these

faces such that they would provide a balanced

representation of the emotional dimensions of

affect and arousal. Two of these faces were

meant to be neutral, involving "blends" of

features; the others were intended to represent the four combinations of positive and

negative affect and high and low arousal. The

faces were ambiguous with regards to age and

sex. The students were asked, "How would

these people rate themselves, if they were

beeped?"

Each student's ratings for these six faces

were aggregated, similar to the aggregations

carried out with the ESM self-reports. Correlations between the self-report scores and the

ratings of faces showed little consistent pattern among the girls, with substantial correlations for the item strong-weak (r = .41 for the

standard deviations, r = .36 for the means)

and correlations for the other items ranging

between r = .26 and -.23. Among the boys,

correlations for the standard deviation scores

were positive, ranging from r = .42 to .29, and

for mean scores, slightly negative, ranging

from r = -.27 to .09.

Results

The analyses involved a series of parallel

multivariate analyses of variance with grade

as the independent variable and the self-reports and ratings of faces as the dependent

variables. All of the dependent variables

were subjected to homogeneity-of-variance

tests prior to the main analyses, which indicated that MANOVA would be an acceptable

method of handling these data. Each significant MANOVA was followed up with univariate tests for polynomial trends. Finally, all

analyses were performed separately for girls

and boys.

To test differences in emotional variability between age groups, we performed a

MANOVA with grade as the independent

variable and students' standard deviations on

each of the six self-ratings scales as the de-

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

""

CO)

in

0

cqcl

cqlCO)

c qm n

0

Cq

,v

vOQ

p

"00Po4

)-,C)0CO

C0

CO)

cd

00m CO)m

0C)~O CO)

>

W0

C ..,

...

C)) ? r-00

C)ItN00in?lcoCO)

0 m0o

0-0

14

z

cj

.I

-4CIO

UQ o~m~

m

ncI 0000i

..0

E-

>

>

ZZ

z~

cd

0n - 4-1~

0 li C)CO

00CO

bC

z CA

~4

a

T~l

L4

(I)

"I

"

k

It

CO)

0 nIT

C)

.. .C)

o . 0....

-4

.iQn

. ...0.It. oc

.cq

.C)

. N.. C.1Z

P..

.

"0"~0

1

O S.1

bo

C) )

ItfCO)f0C)

1

..

...c. .

"

..

>

IIC-1

-

0(

m"in

'I0-.?coC?-I

)co

t-0rco

?-I

?I'm

Cco

C)tP-4

u a D0 Ecd?I -I~0~I?00

in00inIt0) C C ;2

d>

aa o

"c

*..

P.

..

4.

CO)

cd

. . . . .D

.

U

1$

P.

cd

r

rA

A) f*

bCbO

t. PO

m

~?m

a)

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Larson and Lampman-Petraitis

1255

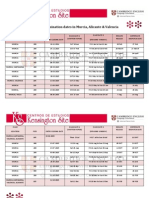

TABLE 2

AGE TRENDS IN THE STANDARD DEVIATION OF REPORTED DAILY EMOTIONALSTATES

GRADE

Girls:

Happy ..............

Cheerful ............

Friendly ............

Alert ................

Strong ..............

Excited .............

N ...................

Boys:

Happy ..............

Cheerful ............

Friendly ............

Alert ................

Strong ..............

Excited .............

N ...................

NOTE.-The

t FOR

LINEAR

TREND

CORRELATION

WITH

GRADE

1.21

1.08

1.12

1.44

1.05

1.46

49

1.18

1.20

1.15

1.44

1.12

1.49

54

1.27

1.27

1.22

1.48

.98

1.58

52

1.25

1.22

1.27

1.52

1.19

1.46

48

1.36

1.21

1.23

1.50

1.12

1.40

37

1.70

2.27

1.68

.85

.81

- .65

.09

.03

.01

.40

.42

.52

.11

.15

.17

- .06

.05

- .03

1.24

1.27

1.24

1.37

1.12

1.44

49

1.18

1.17

1.15

1.43

1.11

1.40

54

1.28

1.25

1.24

1.56

1.17

1.49

52

1.11

1.21

1.16

1.50

1.06

1.42

48

1.12

1.12

.99

1.42

1.00

1.27

37

-1.48

- 1.06

-1.94

.62

-1.09

- 1.23

.14

.29

.05

.53

.28

.22

-.10

-.06

-.06

.05

-.07

-.07

body of the table shows mean standard deviations for each grade level.

pendent variables. This analysis showed an

association between grade level and the standard deviation scores for girls that was just

beyond significance, F(24,914) = 1.49, p =

.06, but no association for boys, F(24,886) =

.93, N.S. Univariate analyses revealed weak,

but significant linear trends for two scales

dealing with affect (cheerful, friendly). Table

2 shows the mean values for each grade level

and correlation coefficients indicating the

magnitude of these linear trends. Since the

quadratic and higher order polynomial terms

were not significant in these (and subsequent)

analyses, they are not shown.

We also performed multivariate analyses

using the standard deviations of the ratings of

faces as the dependent variables. There was

no relation between grade and these scores

among the girls, F(18,173) = .33, N.S., or for

the boys, F(18,155) = .32, N.S. Given that students at the different grade levels attributed

the same range of emotional states to these

standard faces, the age differences among

girls in the variance of self-reported daily

emotions cannot be explained as a function of

response style but rather appear to reflect true

differences in the affective states the older

girls experienced in their daily lives.

Significant age trends in average daily

emotional states were reported by both girls

and boys (see Table 3). MANOVAs were performed using the means of each person's daily

self-reports on the six rating scales as the dependent variables. These analyses revealed a

significant relation between grade level and

average daily mood states for both girls,

F(24,914) = 1.90, p < .01, and boys, F(24,886)

= 1.86, p < .01. Univariate analyses showed

significant linear relations with grade level for

five of the six variables both for girls and boys

(Table 3).

The ratings of the faces again indicated

that the age differences cannot be explained

in terms of variations in response style, at

least for most of these variables. For boys,

there was no significant association between

grade level and the average states attributed

to the drawings of the faces, F(18,155) = 1.18,

N.S. For girls, there was a significant association between grade level and the average ratings of the faces, F(18,173) = 1.69, p < .05.

Polynomial analyses, however, revealed no

univariate trends significant at the .05 level,

and only two of the six items suggested a linear relation with grade that might confound

interpretation of the trends for the self-ratings.

The correlation of grade with the mean happiness girls attributed to the faces was r =

-.15 (p = .23), and the correlation of grade

with the mean perceived cheerfulness of the

faces was r = -.23 (p = .052). Correlations

for the other four items were between r =

-.07 and .21. Therefore, with the possible

exception of the trends for happiness and

cheerfulness among the girls, the age trends

in self-reported daily moods cannot be explained as a difference in response style, but

rather indicate that the older participants experienced less positive average daily states.

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1256

Child Development

TABLE 3

AGE TRENDS IN THE MEANS OF REPORTED DAILY EMOTIONALSTATES

Girls:

Happy ...........

Cheerful ..........

Friendly .........

Alert .............

Strong ...........

Excited ..........

Boys:

Happy ...........

Cheerful .........

Friendly .........

Alert .............

Strong ...........

Excited ..........

35

CORRELATION

WITH

GRADE

t FOR

LINEAR

TREND

5.61

5.34

5.60

4.45

4.46

4.77

5.43

5.25

5.41

4.58

4.68

4.64

5.10

4.92

4.98

4.24

4.28

4.25

5.14

5.11

5.12

4.31

4.34

4.44

4.98

4.83

5.11

4.48

4.42

4.42

-4.22

- 2.64

-3.19

- .42

- 2.07

- 2.07

.001

.009

.002

.68

.04

.04

- .28

-.17

- .21

- .04

-.14

-.14

5.27

4.94

5.26

4.67

4.92

4.53

5.18

4.90

4.93

4.77

4.99

4.40

4.96

5.01

4.88

4.47

4.89

4.38

4.86

4.60

4.78

4.26

4.52

4.26

4.90

4.46

4.75

4.12

4.58'

4.44

-2.81

- 3.03

- 3.04

- 3.30

- 2.62

- 1.08

.005

.003

.003

.001

.009

.48

-.19

-.19

- .20

- .21

-.17

- .06

GRADE

Percentage of Self-Reports

35

30

30

25

25

20

20

15

16

10

10

6

0

-3

-2

Negative

Neutral

+3

+2

+1

-1

Positive

Grade

5th

6th

7th

8th

9th

of self-reported states by grade: girls. (Note: Table shows the mean frequency

FIG. 1.-Frequency

with which students used each of the gradations on the scales to identify their daily emotional states.)

As a supplementary means of examining

these age trends, we evaluated the frequency

with which students at each grade level reported different gradations of positive and

negative mood. For each individual, the percentage of time was calculated that he or she

used each of the 7 points on the six scales to

identify his or her state. Figures 1 and 2 show

the means of these percentages at each grade

level.

It is apparent from this graph that the

greatest age differences occurred for the extreme positive and the mildly negative scale

points. For both girls and boys, the most positive scale point (+3) was used to describe

their states half as often in ninth grade as in

fifth grade. For girls, the linear correlation between grade and percentage in this category

was r = -.21 (p < .001) and for boys was r =

-.22 (p < .001). In place of these extreme

positive states, the older girls reported more

frequent experience of both mildly negative

and mildly positive states, as indicated by

significant linear correlations between frequency and grade level for the scale points

marked +1 (r = .20, p < .01), -1 (r = .21,

p < .001) and -2 (r = .14, p < .05). Older

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Larson and Lampman-Petraitis

35

Percentage of Self-Reports

35

30

30

25

25

20

20

15

15

10

10

5

5

0

1257

0

-3

-2

-1

Negative

+1

Neutral

+2

+3

Positive

FIG.2.-Frequency of self-reportedstates by grade:boys

boys reported more frequent experience only

at the mildly negative - 1 scale point (r = .22,

p < .001). There was no significant age difference in the frequency of extreme negative

states. Contrary to the emotionality hypothesis, the adolescents did not experience more

frequent extreme states but rather experienced more states in this middle emotional

range.

Again, these differences were not replicated in the ratings of faces by the subsample

of 106 students. For boys, the intermediate

2) were

points on the scales (-2,-1,+1,+

used 42.3% of the time by the fifth and sixth

graders and 41.7% by the seventh and eighth

graders; for the girls these intermediate

points of the scales were used for 35.5% of the

time by the younger group and 39.7% by the

older group. There also were no substantive

differences between age groups in the frequency with which positive or negative intermediate scale points were used to rate the

faces. The age differences in self-reported

daily states, therefore, do not reflect an age

difference in response style, but, rather, appear to represent a difference in daily emotional experience.

Discussion

These findings suggest that the onset of

adolescence is not associated with appreciable differences in the variability of emotional

states experienced during daily life. Partici-

pants in the study reported on their moods

when signaled at random times over a week.

Among boys there were no significant trends

across the age period from 9 to 15 in the

intraindividual variability of self-reported

moods. Among girls there was a slight and

only marginally significant age difference in

these standard deviations, accounted for by

positive linear age trends for two mood items

that dealt with affect. Neither boys nor girls

showed an increase in the frequency of extreme negative or positive states.1 Such

findings challenge the hypothesis that adolescence is a time of greatly increased emotionality. At the same time, the data do not suggest an age-related decrease in emotionality;

they do not show the beginnings of the decline in emotional variability that some studies have found between adolescence and

adulthood. Adolescence, then, may be a plateau period during which the emotional lability of childhood is sustained and is manifested within the more sophisticated and

adult-like prism of teenage experience.

While these findings indicated little age

difference in the variability of moods, they do

suggest that the onset of adolescence is associated with changes in average mood. Signaled during their daily lives, there were

fewer occasions when older participants reported extreme positive states and more occasions when they reported mildly negative

ones. For both boys and girls, the average

state-the

emotional baseline-was

lower

1 In separateanalyses we have examined these data using pubertalstatusratherthan gradeas

the independent variable (Richards& Larson,in process).Since many theories explicitly relatethe

emotionalityof adolescence to the biological events of puberty,one might expect pubertalstatusto

show strongerrelations with the dependent variablesconsidered here. The findings of these analyses, however, indicate that pubertalstatus is no strongera predictorof these mood variablesthan

grade.

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1258

Child Development

among older than younger subjects. The absence of comparable age differences in ratings

of emotions in drawings of faces indicates that

these findings cannot be attributed to age differences in response bias.

Two explanations can be considered for

these differences between children's and adolescents' representations of their daily affective states. One explanation is that there are

differences in how younger and older youth

interpret what may be very similar internal

and external daily affective experiences. A

second explanation is that there are real

changes in these internal and external experiences.

The interpretive explanation posits an

adolescent who has become more critical and

discerning in reading internal and external

emotional cues, who may be less willing to

label his or her experience with naively positive superlatives, and who is more able to

detect cues indicative of mildly negative

states. Laboratory research indeed demonstrates that, with increasing age, children's

emotional understanding deepens (Nannis,

1988a, 1988b): their lexicon of emotional

terms expands, they make more complex differentiations of the emotions appropriate to

different situations (Harter, 1980; Schwartz &

Trabasso, 1984; Weiner & Graham, 1984), and

they more frequently consider internal processes in their attributions of emotion (Harris,

Olthof, & Terwogt, 1981; Wolman, Lewis, &

King, 1971). It is conceivable, then, that the

less frequent extreme positive ratings among

the adolescents and the slightly increased

variability with age among the girls reflects an

ability to make finer discriminations of emotional experience. This laboratory research,

however, does not easily account for the overall downward shift in average emotional

states.

The second explanation attributes the

age differences in reported states to real

changes in the affective composition of daily

life across the transition to adolescence. That

is, the downward shift in average states may

reflect an alteration in the balance sheet of

positive and negative affective cues that make

up the individual's daily experience. Such an

alteration might be related to a host of normative changes associated with early adolescence: increasing stressful events (BrooksGunn & Warren, 1989; Coddington, 1972),

the hormonal changes of pubescence (Nottelmann et al., 1987), complex interactions occurring with pubertal development (BrooksGunn & Warren, 1989; Petersen & Taylor,

1980; Simmons, Blyth, Van Cleave, & Bush,

1979), changes in the social environment

(Lewin, 1938), or increased emotional autonomy and decreased parental ego support

(Blos, 1961; Steinberg & Silverberg, 1986).

This explanation is also consistent with the

finding that rates of depressive feelings and

depressive disorders increase with the onset

of adolescence (Rutter, 1986).

The two explanations actually converge

in what they suggest about the daily lives of

children and adolescents. Whether one concludes that there is a real change in the affective composition of their lives or that adolescents just think there is, the outcome is the

same-the adolescent's conscious experience

includes many fewer occasions when the individual feels on top of the world and more

occasions of feeling mildly negative. While

the majority of the daily states they experience are still positive, the overall range of

their experience is markedly lower.

Further research will be required to investigate the causes and consequences of

these alterations in daily experiences. Are

they related to the normative changes associated with early adolescence: increased life

stress, hormonal changes, autonomy from parents? What is the association of these alterations in experience with subsequent development of adolescent problems, particularly

with the high rates of depression found

among girls beginning in mid-adolescence?

Lastly, it is important to consider how these

changes are related to, and might be modified

by, developmental changes in the understanding of emotions and the individual's acquisition of strategies for controlling and regulating them.

References

Adelson, J. (1979, February).Adolescence and the

generalizationgap. Psychology Today, 12, 3337.

Becker, H. S. (1964). Personal change in adult life.

Sociometry,27, 40-53.

Benedict, R. (1938). Continuities and discontinuities in cultural conditioning. Psychiatry, 1,

161-167.

Blos, P. (1961). On adolescence. New York:Free

Press.

Bradburn,N. (1969). The structureof psychological

well-being. Chicago: Aldine.

Brooks-Gunn,J., & Warren,M. P. (1989).Biological

and social contributions to negative affect in

young adolescent girls. Child Development,

60, 40-55.

Campbell, A. (1981). The sense of well-being in

America: Recent patterns and trends. New

York:McGraw-Hill.

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Larson and Lampman-Petraitis

1259

Coddington, R. D. (1972). The significance of life

events as etiologic factors in the diseases of

children: II. A study of a normal population.

Kohlberg, L., LaCrosse, J., & Ricks, D. (1974). The

predictability of adult mental health from

childhood behavior. In B. Wolman (Ed.), Man-

Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 16, 205-

ual of child psychopathology(pp. 1217-1234).

213.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (1987). Validity

and reliability of the experience-sampling

New York: McGraw-Hill.

Larson, R. (1989). Beeping children and adolescents: A method for studying time use and

daily experience. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 18(4), in press.

Larson, R., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1983). The experience sampling method. In H. T. Reis (Ed.),

method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175, 526-536.

Diener, E., Sandvik, E., & Larsen, R. (1985). Age

and sex effects for emotional intensity. Devel-

opmental Psychology,21, 542-546.

Dusek, J., & Flaherty, J. (1981). The development

of the self-concept during the adolescent years.

Monographs of the Society for Research in

Child Development, 46(4, Serial No. 191).

Eichhom, D. (1980). The school. In M. Johnson

(Ed.), Toward adolescence: The middle school,

years (pp. 56-73). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1975). Unmasking the

face. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Fox, V. (1977). Is adolescence a phenomenon of

modem times? Journal of Psychohistory, 1,

271-290.

Freud, A. (1937). The ego and the mechanisms of

defense. New York: International Universities

Press.

Hall, G. S. (1904).Adolescence: Its psychology and

its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education.

New York: Appleton.

Hamilton, D. L. (1965). Personality attributes associated with extreme response style. Psychologi-

cal Bulletin, 69, 192-203.

Harris, P. L., & Olthof, T. (1982). The child's concept of emotion. In G. Butterworth & P. Light

(Eds.), Social cognition: Studies in the development of understanding (pp. 188-209). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harris, P. L., Olthof, T., & Terwogt, M. M. (1981).

Children's knowledge of emotion. Journal of

Child Psychology,22, 247-261.

Harter, S. (1980). A cognitive-developmental approach to children's understanding of affect

and trait labels. In R. Serafica (Ed.), Social-cog-

nitive development in context (pp. 27-61).

New York: Guilford.

Hess, R., & Goldblatt, I. (1957). The status of adolescence in American society: A problem in

social identity. Child Development, 28, 459468.

Hill, J. P., & Holmbeck, G. N. (1986). Attachment

and autonomy during adolescence. In G. J.

Whitehurst(Ed.),Annals of child development

(Vol. 3, pp. 145-189). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Hollingshead, A., & Redlich, F. (1958). Social class

and mental illness: A community study. New

York: Wiley.

Hormuth, S. E. (1986). The sampling of experience

in situ. Journal of Personality,54, 262-293.

Naturalistic approaches to studying social interaction, new directions for methodology of

social and behavioral science (pp. 41-56). San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Larson, R., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Graef, R.

(1980). Mood variability and the psychosocial

adjustment of adolescents. Journal of Youth

and Adolescence, 9, 469-490.

Lewin, K. (1938). Field theory and experiment in

social psychology: Concepts and methods.

AmericanJournal of Sociology, 868-896.

Light, C. S., Zax, M., & Gardiner, D. H. (1965).

Relationship of age, sex, and intelligence level

to extreme response style. Journal of Personal-

ity and Social Psychology,2, 907-909.

Lipsitz, J. (1977). Growing up forgotten. London:

Transaction Books.

Malatesta, C. Z. (1981). Affective development over

the lifespan: Involution or growth? Merrill-

Palmer Quarterly,27, 145-173.

Malatesta, C. Z., & Kalnok, M. (1984). Emotional

experience in younger and older adults. Jour-

nal of Gerontology,39, 301-308.

Malmquist, C. P. (1975). Depressions in childhood

and adolescence. New England Journal of

Medicine, 284, 887-893.

Mead, M. (1928). Coming of age in Samoa. New

York: Morrow.

Montemayor, R. (1986). Family variation in parentadolescent storm and stress. Journal of Adoles-

cent Research, 1, 15-31.

Musgrove, F. (1963). Intergenerational attitudes.

British Journal of Sociology and Clinical Psychology, 2, 209-223.

Nannis, E. D. (1988a). Cognitive-developmental

differences in emotional understanding. In

E. D. Nannis & P. A. Cowan (Eds.), New direc-

tions for child development: Developmental

psychopathology and its treatment (no. 39).

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nannis, E. D. (1988b). A cognitive-developmental

view of emotional understanding and its implications for child psychotherapy. In S. R. Shirk

(Ed.), Cognitive development and child psychotherapy. New York: Plenum.

Nottelmann, E. D., Susman, E. J., Blue, J. H., InoffGermain, G., Dorn, L. D., Loriaux, D. L., Cutler, G. B., & Chrousos, G. P. (1987). Gonadal

and adrenal hormone correlates of adjustment

in early adolescence. In R. M. Lemer & T. T.

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1260

Child Development

Foch (Eds.), Biological-psychological interactions in early adolescence (pp. 303-323).

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Offer, D., & Offer,J. (1975). From teenage to manhood. New York:Basic.

Offer, D., Ostrov, E., & Howard, K. I. (1981). The

adolescent. New York:Basic.

Petersen, A. C. (1988). Adolescent development.

Annual Review of Psychology,39, 583-607.

Petersen, A. C., & Taylor,B. (1980). The biological

approach to adolescence: Biological change

and psychological adaptation. In J. Adelsen

(Ed.), Handbookof adolescent psychology (pp.

117-155). New York:Wiley-Interscience.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent

self-image. Princeton,NJ: PrincetonUniversity

Press.

Russell, J. A., & Ridgeway, D. (1983). Dimensions

underlying children's emotion concepts. Developmental Psychology, 19, 795-804.

Rutter,M. (1986). The developmental psychopathology of depression: Issues and perspectives.

In M. Rutter,C. E. Izard, & R. B. Read (Eds.),

Depression in young people (pp. 3-30). New

York:Guilford.

Rutter, M., Graham,P., Chadwick, O., & Yule, W.

(1976). Adolescent turmoil: Fact or fiction?

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,

17, 35-56.

Schwartz,R. M., & Trabasso,T. (1984). Children's

understandingof emotions. In C. E. Izard, J.

Kagan,& R. B. Zajonc(Eds.), Emotions, cogni-

tions, and behavior (pp. 409-437). Cambridge:

CambridgeUniversity Press.

Sharp,V. (1980). Adolescence. In J. Bemorad(Ed.),

Child development in normality and psychopathology (pp. 174-218). New York:Brunner/

Mazel.

Simmons,R. G., & Blyth, D. A. (1987).Movinginto

adolescence. New York:Aldine De Gruyter.

Simmons,R. G., Blyth, D. A., Van Cleave, E. F., &

Bush, D. M. (1979). Entry into early adolescence: The impactof school structure,puberty,

and early dating on self-esteem. American Sociological Review, 44, 948-967.

Spacks, P. M. (1981). The adolescent idea. New

York:Basic.

Steinberg, L. (1985). Adolescence. New York:

Knopf.

Steinberg,L., & Silverberg,S. B. (1986). The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence.

Child Development, 57, 841-851.

Strober,M. (1986).Psychopathologyin adolescence

revisited. Clinical Psychology Review, 6, 199209.

Weiner, B., & Graham,S. (1984). An attributional

approachto emotional development. In C. E.

Izard, J. Kagan, & R. B. Zajonc (Eds.), Emotions, cognition, and behavior (pp. 167-191).

Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.

Wolman, R. N., Lewis, W. C., & King, M. (1971).

The development of the language of emotions:

Conditions of emotional arousal.Child Development, 42, 1288-1293.

This content downloaded from 155.54.213.13 on Mon, 7 Apr 2014 07:13:21 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Foam Roll Guide 2016 InteractiveDokument15 SeitenFoam Roll Guide 2016 InteractiveMariángel IbarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ASPCC Manual 4 7 14Dokument12 SeitenASPCC Manual 4 7 14javiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ASPCC Manual 4 7 14Dokument12 SeitenASPCC Manual 4 7 14javiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Research: Some Basic Concepts and TerminologyDokument57 SeitenEducational Research: Some Basic Concepts and TerminologySetyo Nugroho100% (11)

- Test It Fix It - FCE Use of English - Upper Intermediate Level PDFDokument89 SeitenTest It Fix It - FCE Use of English - Upper Intermediate Level PDFÁgnes Jassó100% (1)

- Top 4 High Impact Team and Leadership ActivitiesDokument21 SeitenTop 4 High Impact Team and Leadership ActivitiesDave HennesseyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 CAE Paper Based Examination Dates in MurciaDokument3 Seiten2015 CAE Paper Based Examination Dates in MurciaalbervaleraNoch keine Bewertungen

- IELTS Speaking Topics from AIPPG.comDokument2 SeitenIELTS Speaking Topics from AIPPG.comTrang TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculo TafadDokument8 SeitenCurriculo TafadalbervaleraNoch keine Bewertungen

- IELTS Speaking Topics from AIPPG.comDokument2 SeitenIELTS Speaking Topics from AIPPG.comTrang TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2007 Ei-1Dokument30 Seiten2007 Ei-1Wesley Dultra de AlmeidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emotional Intelligence PDFDokument30 SeitenEmotional Intelligence PDFsavinay kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Designed To Move Full ReportDokument142 SeitenDesigned To Move Full ReportalbervaleraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposal For An Action Plan To Combat Violence in SchoolsDokument32 SeitenProposal For An Action Plan To Combat Violence in SchoolsalbervaleraNoch keine Bewertungen

- DramaSpeechDiplomaSyllabus Nov 2013Dokument56 SeitenDramaSpeechDiplomaSyllabus Nov 2013albervaleraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Howdoesvisualmerchandising PDFDokument19 SeitenHowdoesvisualmerchandising PDFRIDHI PRAKASHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tattooing and Civilizing ProcessesDokument22 SeitenTattooing and Civilizing ProcessesAna MariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1 1 476 8200 PDFDokument17 Seiten10 1 1 476 8200 PDFJorge R FreitasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Narrative Therapy and The Affective Turn: Part IDokument20 SeitenNarrative Therapy and The Affective Turn: Part IMijal Akoka RovinskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complex Personality ReportDokument20 SeitenComplex Personality ReportKareen Carlos GerminianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creating A Moral AtmosphereDokument28 SeitenCreating A Moral AtmosphereHay Day RNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavior Modification Perspective On MarketingDokument13 SeitenBehavior Modification Perspective On Marketingjibran112Noch keine Bewertungen

- Emotions and MoodsDokument8 SeitenEmotions and MoodsMuhammad UsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding the Hierarchy of Values According to Max Scheller's CategorizationDokument37 SeitenUnderstanding the Hierarchy of Values According to Max Scheller's CategorizationAngel Sarto CañutalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attitude and Behavior: Haseeb Ahmad MMKT-IAS - 22-R-F19Dokument2 SeitenAttitude and Behavior: Haseeb Ahmad MMKT-IAS - 22-R-F19Haseeb AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Improvement PDFDokument32 SeitenSelf Improvement PDFKapembwa IsaacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation Followed by Exposure. A Phase Based Treatment For PTSD Related To Childhood Abuse PDFDokument8 SeitenSkills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation Followed by Exposure. A Phase Based Treatment For PTSD Related To Childhood Abuse PDFAgustina A.O.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Day (2002) School Reform and Transition in Teacher Professionalism and IdentityDokument16 SeitenDay (2002) School Reform and Transition in Teacher Professionalism and Identitykano73100% (1)

- Why Most of The Students in Buting Senior High School Dislike Mathematics SubjectDokument24 SeitenWhy Most of The Students in Buting Senior High School Dislike Mathematics SubjectJane GamboaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Theoretical Model of Strategic Management of Family Firms A Dynamic Capabilities Approach 2016 Journal of Family Business StrategyDokument11 SeitenA Theoretical Model of Strategic Management of Family Firms A Dynamic Capabilities Approach 2016 Journal of Family Business StrategyAna GsNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Engagement PDFDokument37 SeitenWhat Is Engagement PDFAdnan DaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Borderline Personality DisorderDokument8 SeitenBorderline Personality DisorderVarsha Ganapathi100% (1)

- Interpretable Emotion Recognition Using EEG Signals: Special Section On Data-Enabled Intelligence For Digital HealthDokument11 SeitenInterpretable Emotion Recognition Using EEG Signals: Special Section On Data-Enabled Intelligence For Digital HealthPanos LionasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Behaviour Buying Having and Being Canadian 7th Edition Solomon Solutions Manual 1Dokument18 SeitenConsumer Behaviour Buying Having and Being Canadian 7th Edition Solomon Solutions Manual 1elizabeth100% (34)

- May 2011 IB Psychology Paper 3 ResponsesDokument3 SeitenMay 2011 IB Psychology Paper 3 Responsesngraham95Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ushioda Motivation and SLA PDFDokument17 SeitenUshioda Motivation and SLA PDFŁinzZè KrasniqiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting The Effective Implementation of Senior Secondary Education Chemistry Curriculum in Kogi State, NigeriaDokument5 SeitenFactors Affecting The Effective Implementation of Senior Secondary Education Chemistry Curriculum in Kogi State, NigeriaJASH MATHEWNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affective Factors in Oral English Teaching and LearningDokument5 SeitenAffective Factors in Oral English Teaching and LearningIrinaRalucaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name: Nurul Salihah Binti Abdullah ID: 55213117016 The Facet ModelDokument5 SeitenName: Nurul Salihah Binti Abdullah ID: 55213117016 The Facet ModelSalihah AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- BA12N Chap004Dokument148 SeitenBA12N Chap004Katherine SalvatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- TPM Catalogue of Concepts, Theories and MethodsDokument307 SeitenTPM Catalogue of Concepts, Theories and MethodsThieme HennisNoch keine Bewertungen

- College Student Mental Health AssessmentDokument7 SeitenCollege Student Mental Health AssessmentBianca CarmenNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Am That by Abhishek JaguessarDokument34 SeitenI Am That by Abhishek Jaguessarreedoye21Noch keine Bewertungen

- Davidson Seven Brain and CognitionDokument4 SeitenDavidson Seven Brain and CognitionRicardo JuradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Student Learning Strategic Competence in LearningDokument9 SeitenAnalysis of Student Learning Strategic Competence in LearningKhusniyatu ZulaikhaNoch keine Bewertungen