Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Poesía y Antipoesía

Hochgeladen von

Lg VgOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Poesía y Antipoesía

Hochgeladen von

Lg VgCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

MLR,

91.3, 1996

771

and self-sacrifice for the sake of peace. Thompson also appraises the mechanisms of

theatricality at work in the play by analysing characterization, symbolism, dialogue,

and plot structure.

The translation is accurate in the main, reads well, and has largely succeeded in

preserving the flavour of the original text. There are, however, a few instances of

perhaps excessive imaginative originality on the part of the translator, resulting in

awkward translation; such is the translation ofthe decima on page 44 (I am unable to

transcribe the poem here, for lack of space). The work is almost free of misprints but

there is something missing in 'He prided himself upon his ability to see through the

falseness of others, yet he has not perceived the true character of Campos or the

threat people of Madrid' (p. 24). My only significant reservation about the book has

to do with the poor quality of the print, which is very small, hazy-looking and

sometimes faded, thus making the reading experience less enjoyable. Notwithstanding these criticisms, Thompson's translation is basically sound and a useful piece

suitable for both the classroom and the library.

JOHN CARROLL UNIVERSITY

F . KOMLA AGGOR

Poesiay antipoesia. By NICANOR PARRA. Ed. by HUGO MONTES. {Clasicos Castalia,

204) Madrid: Castalia. 1994. xxiii-h 82 pp. 600 ptas.

In his clearly and solidly constructed introductory pages to this short anthology of

Parra's poems, Hugo Montes is sometimes uneasy with his radically plural,

experimental, uproariously modern, and self-fragmenting subject. For his target

audience (students needing facts) he dutifully (and usefully) catalogues some ofthe

techniques and outrages of some forty years of poetic practice that wilfully both

exceeds and fails the expectations of a vanguardismo that it plunders, alters, banalizes,

exalts, and anachronistically extends. 'No faltan las groserias ni los extranjerismos'

(p. 16); 'El autor crea basicamente desde dos situaciones, a saber, la ironia y el

absurdo' (p. 20); the poet works 'dentro de sus esquemas transgresores' (p. 20) and

sceptical, parodic antipoesia is safely given some origins (Huidobro, and interestingly,

Dario (pp. 21-22)) and a firm grounding in Chilean avant-garde writings

(pp. 14-15). In a detailed exploration oi desacralizacion in poems ofthe 1960s Montes

speaks of'lo que se ha Uamado desmitificacion' (p. 18), a tantalizing reference to a

whole new critical vocabulary appropriately applied to Parra by other critics

(Federico Schopff, Ivan Carrasco, Maria Nieves Alonso, Cilberto Trivifios, William

Rowe) but kept at a distance here with the same caution as is used with Parra

himself.

There is a seven-page 'Evocacion biografica' (a common-sense challenge to the

included poem 'Frases' which states that 'Los poetas no tienen biografia').

Annoyingly, this evocation manages to mention Pablo Neruda when only twenty

words in, threatening to cast a spurious shadow over Parra not for the first time

in Chilean literary history; it also implies (taking at face value an autobiographical

remark of Parra's reported at second hand (p. 9)) that Parra's career as a

professional physicist was a kind of obstacle to the poetry, perhaps here missing the

chance to offer a handhold on the abrupt and slippery surface of those poems which

amalgamate high, radical abstraction, intense concentration on observable facts

and behaviours, and extreme scepticism (for example, 'Los vicios del mundo

moderno'). But it is otherwise engagingly alive to the complexity and liveliness of

Parra as a person and, like the rest ofthe introduction, alert to Chilean specificity.

In Europe, this new anthology is in competition with the selections byJose Miguel

Ibanez Langlois for Seix Barral {Antipoemas: Antologia ig44-ig6g) (currendy out of

772

Reviews

print), with its sharp and much more comprehensive introduction, and that by

Alonso and Trivifios for Visor (1989), Chistespara desorientar a la poesia, which takes its

name from the 1982 collection. Both these anthologies, in their layout and indices,

give a much clearer idea than Montes's of the chronology and development of the

poetry. Montes, of course, goes beyond 1969 and he makes space for more ofthe

experimental fragments, Artefactos (igy^), than Alonso and Trivinos but lets in fewer

ofthe Ghistes, missing out one ofthe better ones: 'Poesia poesia | como si en Chile no

ocurriera nada.' Wry, and grimly comical, it is good to have more Parra on our

shelves and to think again whether his middle-period (anti-)poetry is really just a

starting-point for 'poetas mayores el Neruda de Estravagario por ejemplo y

muchos poetas nuevos' (p. 23) or something quite different.

UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE

CHRIS PERRIAM

A Marxist Reading of Fuentes, Vargas Llosa and Puig. By VICTOR MANUEL DURAN.

Lanham, MD, New York, and London: University Press of America. 1994.

xiv-l-118 pp.

Considering the bibliography that already exists on Vargas Llosa, Fuentes, and

Puig, writing on their works and finding a new slant that allows the critic room to

see things in a new light is a difficult task indeed. This, however, is the task that

Victor Manuel Duran has undertaken with this book. Despite the title, however, the

study deals with three specific novels: La casa verde, La muerte de Artemio Cruz, and

Boquitas pintadas. It contains four chapters: the first is a sort of overview of Marxist

literary theory, the second is entitled 'A Marxist Reading of Vargas Llosa's La casa

verde', and the third and the fourth are Marxist readings of Z^ muerte de Artemio Cruz

and Boquitas pintadas, respectively.

The Marxist elements that emerge from the chapter on Marxist literary theory

are selective and fail to give the reader a complete overview of this particular literary

approach and its main objectives. For example, no mention is made of the link

between Marxist criticism and ideology, and the relationship that Marxist criticism

shares with the sociological approach to literature is not explored. Also, a brief

account of how this approach has evolved since its inception would have been

useful. In addition, the author should have taken more care to consult the original

works where available, instead of quoting them through secondary sources.

On various occasions, Duran states that the novels in question are not Marxist

novels and that he is simply offering a Marxist reading of them. However, by

applying only selective aspects of Marxist theory, he ends up not giving a Marxist

reading at all. The impression is given that for him any setting, character, or

historical event that can be traced back to reality is Marxist. Moreover, there are

other, rather fundamental, problems with this book. For example. Chapter 2 deals

with La casa verde, but Duran seems content to limit himself to endorsing existing

criticism on this novel. Long, frequent quotations from other works on the novel

and continuous references to other criticism undermine the very purpose of this

study.

Similarly, the chapters on La muerte de Artemio Cruz and Boquitas pintadas do not

give the reader a reasoned analysis of these novels based on Marxist principles.

Some readers may find that what is said about these novels is quite ordinary and

routine, and that it does not add very much to the existing knowledge on the works.

The reader may also wonder why forty pages are dedicated to Boquitas pintadas as

opposed to twenty-five each to the other two novels. I would also question the

author's choice ofthe brief but not very representative bibliography on these novels.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Test For Poetry (On Zukofsky)Dokument210 SeitenA Test For Poetry (On Zukofsky)John JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Mythography (R. Scott Smith, Stephen M. Trzaskoma, (Editors) ) (Z-Library)Dokument625 SeitenThe Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Mythography (R. Scott Smith, Stephen M. Trzaskoma, (Editors) ) (Z-Library)Félix Algar FenoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 3 Creative NonfictionDokument37 SeitenModule 3 Creative Nonfictionelmer rivero0% (1)

- A Brief History of English LiteratureDokument1 SeiteA Brief History of English Literatureferchuland320% (1)

- Junior High Year Plan: By: Emily MacquarrieDokument3 SeitenJunior High Year Plan: By: Emily Macquarrieapi-376504271Noch keine Bewertungen

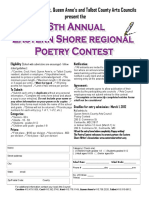

- Caroline, Cecil, Kent, Queen Anne's and Talbot County Arts Councils Present TheDokument2 SeitenCaroline, Cecil, Kent, Queen Anne's and Talbot County Arts Councils Present ThegeorgerouseNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 - Chapter 3Dokument22 Seiten08 - Chapter 3hussein njmNoch keine Bewertungen

- English GR 2Dokument14 SeitenEnglish GR 2Jovancy PaulrajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consolidated 3-4 Semester English Syllabus-71-76Dokument6 SeitenConsolidated 3-4 Semester English Syllabus-71-76SaumyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 5Dokument14 SeitenModule 5GLORIFIE PITOGONoch keine Bewertungen

- Translation & Communication, Graduation Project by Ahmed Fahmy Alfar, 2000Dokument11 SeitenTranslation & Communication, Graduation Project by Ahmed Fahmy Alfar, 2000Ahmed Fahmy Alfar100% (1)

- Karthavirya Dvadasha Nama StotramDokument2 SeitenKarthavirya Dvadasha Nama Stotrammlalithssk0% (1)

- Inferring Speaker's Tone, Mood and PurposeDokument51 SeitenInferring Speaker's Tone, Mood and PurposeAhzille Vendivil-GasparNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arabic Paleography by Nabia AbbottDokument45 SeitenArabic Paleography by Nabia AbbottSohailadnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reference BooksDokument3 SeitenReference Bookssekhar sivaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPT English Form 1 Smidi 2020Dokument10 SeitenRPT English Form 1 Smidi 2020Nur IzzatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nrsimha StotrasDokument60 SeitenNrsimha StotrasinternetidentityscriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rig Veda English Translation Part 7-8Dokument153 SeitenRig Veda English Translation Part 7-8Aelfric Michael AveryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mcgill-Queen'S University Press Challenging CanadaDokument29 SeitenMcgill-Queen'S University Press Challenging CanadadattarayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mantra PurascharanDokument9 SeitenMantra Purascharanjatin.yadav1307100% (1)

- 21st Century Literature Notes For Grade 11 (1st Semester)Dokument9 Seiten21st Century Literature Notes For Grade 11 (1st Semester)shieeesh.aNoch keine Bewertungen

- BORANG PBD 2021 NewDokument71 SeitenBORANG PBD 2021 NewKhairul NisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Variety EntertainmentDokument138 SeitenVariety Entertainmenttv1943Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sayaka Murata (Japan) BiographyDokument3 SeitenSayaka Murata (Japan) BiographyMarvin CanamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Postcolonial Imagination and Postcolonial TheoryDokument11 SeitenPostcolonial Imagination and Postcolonial TheoryDUBIOUSBIRDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jayanta Mahapatra PoemsDokument13 SeitenJayanta Mahapatra PoemsAastha SuranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reglas de AccentosDokument3 SeitenReglas de AccentosAny L HenaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Narco PolisDokument2 SeitenNarco PolisVikram JohariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yorke Microfilm Index PDFDokument72 SeitenYorke Microfilm Index PDFDiletta Anselmi100% (2)