Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Rocky Mountain Gun Owners and Colorado Campaign For Life's Preliminary Injunction Brief

Hochgeladen von

Colorado Ethics WatchOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rocky Mountain Gun Owners and Colorado Campaign For Life's Preliminary Injunction Brief

Hochgeladen von

Colorado Ethics WatchCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 16

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO

Civil Action No. 1:14-cv-02850

ROCKY MOUNTAIN GUN OWNERS, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

SCOTT GESSLER, et al.,

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION

FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

Colorados electioneering communication definition is an unconstitutional

political IED lying in wait for unsuspecting political speakers. The definition is so broad

that it encompasses a nearly limitless array of speech protected by the First

Amendment, including political speech, which has a cherished and protected place in

American jurisprudence. As a result, under Colorado law, a speaker only has $999.99

worth of freedom of speech.

Discussion of public issues and debate on the qualifications of candidates are

integral to the operation of the systems of government established by our Constitution.

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 14 (1976). [T]here is practically universal agreement that

a major purpose of th[e] [First] Amendment was to protect the free discussion of

governmental affairs, . . . of course includ(ing) the discussions of candidates. Id.

(quoting Mills v. Alabama, 384 U.S. 214, 218 (1966)).

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 16

The First Amendment also protects political association. See NAACP v.

Alabama, 357 U.S. 449, 460 (1958) (Effective advocacy of both public and private

points of view, particularly controversial ones, is undeniably enhanced by group

association.).

It is hardly a novel perception that compelled disclosure of

affiliation with groups engaged in advocacy may constitute

a(n) effective . . . restraint on freedom of association. . . .

This Court has recognized the vital relationship between

freedom to associate and privacy in ones associations. . .

Inviolability of privacy in group association may in many

circumstances be indispensable to preservation of freedom

of association, particularly where a group espouses dissident

beliefs.

Id. at 462.

The freedom to speak and to associate are core First Amendment values.

Colorado law, however, is designed to quash these cherished rights on the eve of an

election, when the electorates ear is most inclined to listen, and when the speech is

most likely to make a difference. The electioneering communication definition

encompasses almost all speech referencing a political candidate in the weeks before an

election. In addition, Colorados statutory scheme allows private citizens to prosecute a

cause of action against speakers who run afoul of this definition. The statute

encourages political shenanigans from opponents who dislike or disapprove of the

speakers viewpoint and imposes asymmetric burdens on speakers like the Plaintiffs to

defend an enforcement action at election time when their voice can be most effective.

Plaintiffs respectfully seek a preliminary injunction enjoining enforcement of any

provision of Colorado law that relies upon the electioneering communication definition.

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 3 of 16

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

1. The Plaintiffs

Rocky Mountain Gun Owners (RMGO) is a Colorado, non-profit corporation,

which is exempt from federal income taxes under I.R.C. 501(c)(4). Compl. 12. It is

Colorados largest state-based, Second Amendment grassroots lobbying organization.

Compl. 12. RMGOs stated mission is to defend Coloradans Second Amendment

right to keep and bear arms from all its enemies, and advance those God-given rights

by educating the people of Colorado and urging them to take action in the public policy

process. Compl. 13.

Colorado Campaign for Life (CCFL) is a Colorado non-profit corporation, which

is also exempt from income taxes under I.R.C. 501(c)(4). Compl. 15. It is a

Colorado-based and focused grassroots, pro-life lobbying organization. Compl. 15.

CCFLs mission is to promote the passing of pro-life legislation, such as the Life at

Conception Act, and to lobby for support of such public policy positions. Compl 16.

In furtherance of their respective missions, RMGO and CCFL engage in issuedriven speech to inform Coloradans about the public policy positions of political

candidates on the Second Amendment (RMGO) and abortion (CCFL). Compl. 14,

17. As 501(c)(4) organizations, Plaintiffs are not obligated to disclose the identities of

their members, donors, and supporters. Compl. 12, 15.

2. Statutory Background

Article XXVIII of the Colorado Constitution was enacted to address the potential

for corruption and the appearance of corruption of large campaign contributions as well

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 4 of 16

as to address the alleged outsized influence of wealthy individuals, corporations, and

special interest groups on the political process through those large campaign

contributions. Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 1.

Article XXVIII, in conjunction with Colorados Fair Campaign Practices Act

(FCPA), Colo. Rev. Stat Ann. 1-45-101, et seq., act as Colorados primary campaign

finance laws imposing various reporting and disclosure requirements on speakers

engaged in an electioneering communication, which is defined as:

[A]ny communication broadcasted by television or radio, printed in a newspaper

or on a billboard, directly mailed or delivered by hand to personal residences or

otherwise distributed that:

(I) Unambiguously refers to any candidate; and

(II) Is broadcasted, printed, mailed, delivered, or distributed within thirty

days before a primary election or sixty days before a general election; and

(III) Is broadcasted to, printed in a newspaper, distributed to, mailed to,

delivered by hand to, or otherwise distributed to an audience that includes

members of the electorate for such public office.

Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 2(7); see also Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. 1-45-103(9).1

Any person spending more than $1,000 per calendar year on such

electioneering communications is required to submit periodic reports to the Secretary

of State, that include the amount of money spent on such communications and identify

1

Article XXVIII and the FCPA both exclude from the definition of electioneering

communication the following: (I) Any news articles, editorial endorsements, opinion or

commentary writings, or letters to the editor printed in a newspaper, magazine or other

periodical not owned or controlled by a candidate or political party; (II) Any editorial

endorsements or opinions aired by a broadcast facility not owned or controlled by a candidate or

political party; (III) Any communication by persons made in the regular course and scope of their

business or any communication made by a membership organization solely to members of such

organization and their families; (IV) Any communication that refers to any candidate only as part

of the popular name of a bill or statute. Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 2(7); see also Colo. Rev. Stat.

Ann. 1-45-103(9).

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 5 of 16

the name, address, occupation, and employer of any person that contributed more than

$250 to fund the electioneering communication. Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 6(1); Colo.

Rev. Stat. Ann. 1-45-108.

The Secretary of State is responsible for enforcing and promulgating rules in

furtherance of these campaign finance provisions. See Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 9.

Among other penalties, violators shall be subject to a civil penalty of at least double

and up to five times the amount contributed, received, or spent in violation of the

applicable provision. Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 10(1). A failure to file the appropriate

statement or other information required under Article XXVIII and the FCPA also subjects

violators to a fine of $50 per day. Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 10(2).

Colorados statutory scheme also permits any person to pursue a private action

to enforce Colorados campaign finance laws by filing a complaint with the Secretary of

State. See Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 9(2)(a). After a complaint is filed, the Secretary is

required to refer it to an administrative law judge. See Colo. Const. art. XXVIII,

9(2)(a). The complaining party is allowed to take discovery including deposing the

speaker and obtaining records though the use of subpoenas duces tecum. Compl. Exs.

F, G. The judge must hold a hearing within fifteen days of the complaint being referred

and must render a decision within fifteen days of that hearing. See id. Such decisions

are reviewable by the court of appeals. See id.

The Secretary of State may enforce a final decision by bringing an enforcement

action. See Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 9(2)(a). If, however, the Secretary of State fails

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 6 of 16

to file an enforcement action within thirty days of the decision, the complainant may file

its own private action to enforce the decision. See id.

3. Impact of the Regulation Scheme on Plaintiffs

a. Plaintiffs June, 2014, Primary Mailings

In mid-June, 2014, CCFL sent mailers to Republican primary voters in Colorado

Senate Districts 19 and 22. Compl. 30; Compl. Exs. A, B. In early June, 2014,

RMGO sent a mass mailing to Republican primary voters in Colorado Senate Districts

19 and 22. Compl. 32; Compl. Ex. C. The mailers unambiguously referred to

candidates for office in Colorado and cost more than $1,000. Compl. 31, 33. The

communications did not expressly or impliedly advocate for the election or defeat of a

particular candidate. Compl. 36. The communications were mailed to voters within

Colorado Senate Districts 19 and 22 within thirty days of the June 24, 2014, primary

election. Compl. 34. Neither CCFL nor RMGO filed a report to the Secretary of State

of the State of Colorado reflecting donor information. Compl. 35. Plaintiffs intend to

continue to distribute similar issue-based communications in the future to inform their

constituencies of the positions of potential candidates on issues surrounding the

Second Amendment (RMGO) and/or abortion (CCFL). Compl. 36.

b. Private Action by Colorado Ethics Watch

On September 9, 2014, Defendant, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in

Washington (CEW),2 filed a private enforcement action against Plaintiffs. Compl.

Defendant Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington t/a Colorado Ethics

Watch is registered to operate as a foreign corporation with the Colorado Secretary of State

under the trade name Colorado Ethics Watch. The private enforcement action was initiated

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 7 of 16

37. CEWs complaint alleges that Plaintiffs mailings fall within the definition of an

electioneering communication and that Plaintiffs failed to file the appropriate reports

and disclosure of contributors. Compl. 38; Compl. Ex. D. CEW demands that Plaintiffs

be fined for each day they fail to file those reports. Compl. 39.

After receiving CEWs complaint, Defendant Scott Gessler, Colorado Secretary

of State, referred the action to an administrative law judge for adjudication. Compl.

41. This matter has been assigned Case No. OS 20140025 in the Colorado Office of

Administrative Courts. Compl. 41. A hearing on the merits was scheduled to be held

on November 6, 2014, at 9:00 a.m., before the Office of Administrative Courts. Compl.

42; Compl. Ex. E. That hearing has been continued.3 The statutory scheme permits

pre-trial discovery like in a civil action and CEW has previously noticed C.R.C.P.

30(b)(6) depositions and C.R.C.P. 34(a)(1) document requests upon RMGO and CCFL.

Compl. 45; Compl. Exs. F, G. The hearing will be a full adversary proceeding, much

akin to a bench trial. Compl. 44; Compl. Ex. E.4

Plaintiffs are subject to great economic harm as a result of their defense of this

private enforcement action. Compl. 46. Aside from incurring legal fees, the

inconvenience of pre-trial discovery, and preparing for trial during election season, each

organization is subject to extensive fines if found guilty of violating these laws. Compl.

46. Yet, this economic harm pales in comparison to the chilling effect this statutory

under CEWs name. Therefore, for the purposes of this memorandum, Plaintiffs will refer to this

defendant as CEW.

3

The Office of Administrative Courts has not provided a new hearing date.

4

Even before a hearing has been held, CEW has continued to demand that RMGO and

CCFL file the disclosure responses. Compl. 46; Compl. Ex. H.

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 8 of 16

scheme has on the First Amendment rights of the Plaintiffs and other speakers.

Plaintiffs seek this preliminary injunction to protect those freedoms.

ARGUMENT

A party seeking a preliminary injunction must demonstrate: 1) likelihood of

success; 2) irreparable harm absent a preliminary injunction; 3) that the balance of

equities tips in the moving partys favor; and 4) that the injunction is in the public

interest. Republican Party of N.M. v. King, 741 F.3d 1089, 1092 (10th Cir. 2013).

I.

Plaintiffs are Likely to Succeed on the Merits.

A. The electioneering communication definition is overly broad.

A challenge on overbreadth grounds centers on whether the relevant statute

reaches a substantial amount of constitutionally protected speech. Wisconsin Right to

Life v. Barland, 751 F.3d 804, 835-36 (7th Cir. 2014). However, in the context of a

statute targeting speech at the time of a campaign, this test is satisfied by definitionas

all political speech is always protected under the First Amendment. See id. at 836.

Thus, government may regulate in th[is] area only with narrow specificity. Buckley v.

Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 41 n.48 (1976).

To comply with the narrow specificity requirement, government may only

regulate express election advocacy or its equivalent. Barland, 751 F.3d at 836.

Express advocacy, as defined in Buckley, includes the use of words such as vote for,

elect, support, cast your ballot for, Smith for Congress, vote against, defeat,

reject. Buckley, 424 U.S. at 44 n.52. Any government regulation of issue-driven

political expression outside of the sphere of express election advocacy is

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 9 of 16

constitutionally forbidden. Barland, 751 F.3d at 811. Yet this is exactly the type of

issue-driven political expression at issue here that is improperly regulated under

Colorados statutory scheme.

Instead of merely addressing the stated purpose of Article XXVIII, the FCPAs

sweep encompasses a vast array of political speech because of how it defines an

electioneering communication. No party that spends more than $1,000 and merely

mentions a candidates name near election time to the electorate escapes this statutory

schemes reach. Colo. Const. art. XXVIII, 2(7); see also Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. 1-45103(9) (2014). It is this regulation of protected speech, outside of the governments

power to regulate, that renders this definition of electioneering communication

unconstitutionally overbroad.

The Seventh Circuit recently examined a similar statute in Barland. 751 F.3d at

837. In addition to the three definitional requirements set forth in Colorados statute, to

be considered an electioneering communication under Wisconsins statute, the speech

was required either to (1) refer to the personal qualities, character, or fitness of that

candidate; (2) support or condemn that candidate's position or stance on issues; or (3)

support or condemn that candidate's public record. Id. at 837.

Even though the reach of Wisconsins statute was much less broad than

Colorados, the Seventh Circuit ruled that Wisconsins statute was unconstitutionally

overbroad. Id. at 838. The Court determined that, during the 30/60 day window before

an election, essentially all political speech about issues counted as express advocacy

under the Wisconsin statute triggering PAC-like requirements if a speaker named

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 10 of 16

and said pretty much anything at all about a candidate for office. Id. at 836-37. Given

the significant expense, burden, and chilling effect of PAC-like reporting and disclosure

on ordinary citizens, grassroots issue-advocacy groups, and 501(c)(4) social-welfare

organizations, Wisconsins statute was overbroad precisely because it was not limited to

regulating speech that expressly advocated for or against candidates. Id. at 837-38.

While Wisconsins statute attempted to regulate only speech that discussed a

candidates qualifications, Colorados statute has a limitless reach so long as the

candidates name is unambiguously included in any communication. Colo. Const. art.

XXVIII, 2(7). Thus, if Wisconsins more narrowly-tailored statute is unconstitutionally

overbroad, it necessarily follows that Colorados far more broad statute must be

similarly unconstitutional. The logic is inescapable.

B. The $1,000 expenditure threshold is too low.

The same communications at issue here would not be considered electioneering

communications if the Plaintiffs had spent less than $1,000. Because the Plaintiffs

spent more than $1,000 on these communications, they are subject to PAC-like

reporting and disclosure requirements. PAC-like reporting and disclosure requirements

are impermissibly burdensome to political speech that does not expressly advocate for

or against the election of candidates and acts as the equivalent of prior restraint. See

Citizens United, 558 U.S. at 335. These burdens are not merely clerical or

administrative, they are restrictions on speech and association. Coal. for Secular Govt

v. Gessler, No. 1:12-cv-01708-JLK-KLM, 2014 WL 509227, at *1 (D. Colo. Oct. 10,

2014)(citing FEC v. Massachusetts Citizens for Life, 479 U.S. 238, 254 (1986)). The

10

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 11 of 16

disclosure of an organizations contributors is disfavored because it impinges upon the

freedom of association. Davis v. FEC, 554 U.S. 724, 744 (2008) ([C]ompelled

disclosure, in itself, can seriously impinge on privacy of association and belief

guaranteed by the First Amendment.).

Forced disclosure regimes implicate two basic concerns. First, forced disclosure

of donors burdens associational privacy interests. Barland, 751 F.3d at 840; see also

Sampson v. Buescher, 625 F.3d 1247, 1255 (10th Cir. 2010) (Reporting and disclosure

requirements . . . can infringe on the right of association.). Second, PAC-like

registration and reporting requirements impose heavy administrative burdens, creating

disincentives to participation in election-related speech. Id. at 840; see also Citizens

United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310, 337-38 (2010), Sampson, 625 F.3d at 1255.

Burdens on speech may be upheld under the exacting scrutiny standard only if

there is a substantial relation between the disclosure requirement and a sufficiently

important governmental interest. Sampson, 625 F.3d at 1255. Exacting scrutiny is not

a loose form of judicial review. Barland, 751 F.3d at 840. Rather [t]o withstand this

scrutiny, the strength of the governmental interest must reflect the seriousness of the

actual burden on First Amendment rights. Sampson, 625 F.3d at 1255.

The Supreme Court has recognized three justifications for reporting and

disclosing campaign finances. Buckley, 424 U.S. at 67-68. First, disclosure

requirements are an essential means of gathering the data necessary to detect

violations of . . . contribution limitations. Id. at 67. Second, disclosure requirements

deter actual corruption and avoid the appearance of corruption by exposing large

11

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 12 of 16

contributions and expenditures to the light of publicity. Id. at 67. Third, disclosure

requirements benefit the publics informational interest. See id. at 67. None of these

justifications are satisfied here.

Section 6(1) of the Colorado Constitution provides that any person spending

more than $1,000 on electioneering communications during a calendar year must report

to the Secretary of State and disclose the name, address, occupation and employer of

each donor who gave more than $250 to fund the communications. Id. There is simply

no governmental interest in the identity, occupation, or employer of a donor who gave

$250, or more, to fund an issue-based communication that does not advocate for or

against any candidate. Two recent cases, Sampson and Coalition for Secular

Government, illustrate that point and clearly show why Colorados $1,000 expenditure

threshold does not survive the exacting scrutiny standard.

In Sampson, the Tenth Circuit noted the disconnect between the avowed

purpose of Article XXVIIIs disclosure requirements and its actual effect on First

Amendment rights. 625 F.3d at 1254. The Court held that the cost and burden of

disclosure was not substantially related to any of the permissible justifications for

requiring disclosure when imposed on a group that spent a small amount of money (less

than $1,000 excluding attorneys fees) opposing a ballot issue. See id. at 1261. The

Court also held that the value of the type of information subject to disclosure to the

voters declines drastically as the value of an expenditure or contribution sinks to a

negligible level especially when the communications did not involve the expenditure of

tens of millions of dollars on ballot issues presenting complex policy issues. Id. at 1259-

12

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 13 of 16

61 (emphasis added and citations omitted). Because there was not a sufficiently

substantial relation between the requirement imposed and the governmental interest,

the court found the statute did not satisfy exacting scrutiny. Id. at 1261.

Similarly, in Coalition for Secular Government, Judge Kane held that

expenditures of $3,500 to distribute a paper regarding personhood could not trigger

registration or disclosure. Coal. for Secular Govt v. Gessler, No. 1:12-cv-01708-JLKKLM, 2014 WL 509227, at *1 (D. Colo. Oct. 10, 2014). Notably, Judge Kane

determined that the governmental interest in knowing the source of such small

expenditures was highly limited. Id. at *5. The burdens imposed on a speaker

outweighed such limited informational interest, because those burdens were not merely

clericalthey were restrictions on speech and association. Id. It logically follows that if

the $3,500 expenditure threshold was too low in that case, then the $1,000 expenditure

threshold at issue here must similarly be unconstitutional.

Instead of regulating significant expenditures on electioneering

communications, like the expensive television commercials cited in Article XXVIII, this

law reaches all the way down to regulate persons involved in neighborhood disputes

that have the temerity to mention a candidates name during election time and spend

more than $1,000 to do it. See e.g. Sampson, 625 F.3d at 1255; see also Barland, 751

F.3d at 837. Clearly a Constitutionally untenable situation.

II.

Plaintiffs Will Suffer Irreparable Harm Absent an Injunction.

The loss of First Amendment Freedoms, even for minimal periods of time,

unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury. Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347, 373

13

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 14 of 16

(1976); Pac. Frontier v. Pleasant Grove City, 414 F.3d 1221, 1235 (10th Cir. 2005)

([W]e therefore assume that plaintiffs have suffered irreparable injury when a

government deprives plaintiffs of their commercial speech rights.) The harm is

particularly irreparable where, as here, a plaintiff seeks to engage in political speech, as

timing is of the essence in politics and a delay of even a day or two may be intolerable.

Klein v. City of San Clemente, 584 F.3d 1196, 1208 (9th Cir. 2009) (internal quotation

marks and alteration omitted).

III.

The Balance of Equities Favors an Injunction.

A threatened injury to a plaintiffs constitutionally protected speech outweighs

whatever damage the preliminary injunction may cause Defendants inability to enforce

what appears to be an unconstitutional statute. ACLU v. Johnson, 194 F.3d 1149, 1163

(10th Cir. 1999). Absent an injunction, a wide range of speech, both political and nonpolitical, particularly issue-driven speech, is restricted. Moreover, the private

enforcement action, including its discovery requirements, are potentially ruinous in time

and cost to small groups like the Plaintiffs, and exposes possibly sensitive strategy

information to political opponents. Plaintiffs must divert from their mission to defend

against this private enforcement action at the time when the public is most inclined to

hear their message. There is no corresponding cost or hardship to the Defendants.

IV.

The Public Interest is Served by Protecting First Amendment Rights.

A state does not have an interest in enforcing a law that is likely constitutionally

infirm. Chamber of Commerce of U.S. v. Edmonson, 594 F.3d 742, 771 (10th Cir.

2010). Moreover, a preliminary injunction vindicating constitutional rights is always in

14

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 15 of 16

the public interest. See Pac. Frontier v. Pleasant Grove City, 414 F.3d 1221, 1237

(10th Cir. 2005) (Vindicating First Amendment freedoms is clearly in the public

interest.).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this Court should enter an order preliminarily enjoining

the Defendants from enforcing any provision of Colorado law that relies upon the

electioneering communication definition.

Dated: November 7, 2014

Respectfully submitted,

/s/ David A. Warrington

David A. Warrington

Laurin H. Mills

Andrew J. Narod

Paris R. Sorrell

LeClairRyan, A Professional Corporation

2318 Mill Road, Suite 1100

Alexandria, Virginia 22314

Telephone: (703) 684-8007

Facsimile: (703) 647-5999

david.warrington@leclairryan.com

laurin.mills@leclairryan.com

andrew.narod@leclairryan.com

paris.sorrell@leclairryan.com

James O. Bardwell

Rocky Mountain Gun Owners

501 Main Street, Suite 200

Windsor, CO 80550

Telephone: (877) 405-4570

Facsimile: (202) 351-0528

jb@nagrhq.org

Counsel for Plaintiffs Rocky Mountain Gun

Owners and Colorado Campaign for Life

15

Case 1:14-cv-02850-CMA-KLM Document 24 Filed 11/07/14 USDC Colorado Page 16 of 16

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on November 7, 2014, I electronically filed the foregoing

document with the Clerk of Court using the CM/ECF system, which will send notice of

such filing to counsel of record who are registered with CM/ECF.

/s/ David A. Warrington

16

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Oct 2017 Comment On CPF RulemakingDokument2 SeitenOct 2017 Comment On CPF RulemakingColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electioneering Gap ReportDokument1 SeiteElectioneering Gap ReportColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hickenlooper Calendar Oct-Dec 2016Dokument155 SeitenHickenlooper Calendar Oct-Dec 2016Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Re: Draft Position Statement Regarding Home Rule Municipalities Ethics CodesDokument10 SeitenRe: Draft Position Statement Regarding Home Rule Municipalities Ethics CodesColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Telluride Code of Ethics 2016Dokument12 SeitenTelluride Code of Ethics 2016Colorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Logan County Employee Handbook Attachment DDokument2 SeitenLogan County Employee Handbook Attachment DColorado Ethics WatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- 302a PDFDokument39 Seiten302a PDFTsiggos AlexandrosNoch keine Bewertungen

- PHILI 1100 Reviewer 1Dokument1 SeitePHILI 1100 Reviewer 1Tristan Jay NeningNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept PDokument5 SeitenConcept PMary Ann RosalejosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tolentino Vs SecretaryDokument7 SeitenTolentino Vs SecretaryHansel Jake B. PampiloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule of Law in Context of BangladeshDokument5 SeitenRule of Law in Context of BangladeshShabnam BarshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- China Relations Core - Berkeley 2016Dokument269 SeitenChina Relations Core - Berkeley 2016VanessaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lowe v. Tramont Corporation Et Al - Document No. 3Dokument3 SeitenLowe v. Tramont Corporation Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case StudyDokument5 SeitenCase StudyAnuraagSrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humboldt PresDokument36 SeitenHumboldt PresbbirchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arnault vs. Balagtas DigestDokument3 SeitenArnault vs. Balagtas DigestRany Santos100% (1)

- Vision IasDokument16 SeitenVision Iasbharath261234Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pembagian Sesi Tes TulisDokument8 SeitenPembagian Sesi Tes TulisRangga SaputraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Williams Broadcasting 21Dokument3 SeitenWilliams Broadcasting 21Ethan GatesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nigeria Port Autority ASSIG.Dokument11 SeitenNigeria Port Autority ASSIG.ChristabelNoch keine Bewertungen

- 776-The Future of Sustainable Cities - Critical Reflections John Flint Mike Raco 1847426670 Policy Press 2012 272 $115 PDFDokument271 Seiten776-The Future of Sustainable Cities - Critical Reflections John Flint Mike Raco 1847426670 Policy Press 2012 272 $115 PDFpouyad100% (1)

- Tender RRDokument1 SeiteTender RRAsron NizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cop City Signature RulingDokument32 SeitenCop City Signature RulingJonathan RaymondNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Business V SurecompDokument1 SeiteGlobal Business V SurecompAngelo Rayos del SolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ambasciata D'italia A Teheran Document Checklist For Tourist VisaDokument1 SeiteAmbasciata D'italia A Teheran Document Checklist For Tourist VisaokksekkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Design in Clinical Psychology 4th Edition Alan E. Kazdin Test BankDokument5 SeitenResearch Design in Clinical Psychology 4th Edition Alan E. Kazdin Test Banksax0% (2)

- Occeña Law Office For Petitioner. Office of The Solicitor General For RespondentsDokument3 SeitenOcceña Law Office For Petitioner. Office of The Solicitor General For RespondentsPat RanolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cesar Chavez - Civil-Rights ChampionDokument20 SeitenCesar Chavez - Civil-Rights ChampionasadfffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Province of Zamboanga Del Norte v. City of Zamboanga SNMCDokument3 SeitenProvince of Zamboanga Del Norte v. City of Zamboanga SNMCCamille CalvoNoch keine Bewertungen

- S1, 2. Obama Campaign Rewrites Fundraising Rules by Selling Merchandise - HuffPostDokument3 SeitenS1, 2. Obama Campaign Rewrites Fundraising Rules by Selling Merchandise - HuffPostDeeksha SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agreement On Custody and SupportDokument4 SeitenAgreement On Custody and SupportPrime Antonio Ramos100% (4)

- CRM2020-346 Decision and DocumentsDokument71 SeitenCRM2020-346 Decision and DocumentspaulfarrellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quiz 1 IB1606 LOG LAW102Dokument4 SeitenQuiz 1 IB1606 LOG LAW102Hữu Đạt ĐồngNoch keine Bewertungen

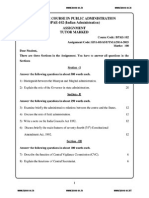

- Bpae 102Dokument7 SeitenBpae 102Firdosh KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Redone NCDokument9 SeitenRedone NCSaw HJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annexure 'A' Self - DeclarationDokument3 SeitenAnnexure 'A' Self - DeclarationSandeep ShahNoch keine Bewertungen