Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Dhs TF Whitepaper

Hochgeladen von

CharleneCleoEibenOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Dhs TF Whitepaper

Hochgeladen von

CharleneCleoEibenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

UNTANGLING THE WEB:

CONGRESSIONAL OVERSIGHT AND THE

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY

A WHITE PAPER OF THE CSIS-BENS TASK FORCE

ON CONGRESSIONAL OVERSIGHT OF THE

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY

DECEMBER 10, 2004

December 10, 2004

The principles below have been endorsed by Norman Augustine, Jeffrey Bergner, Charles Boyd, Raymond

Chambers, Thomas Foley, Maurice Greenberg, John Hamre, Robert Livingston, Charles Robb, Warren Rudman,

Frederick Smith, and J.C. Watts.

Task Force Co-Chairs:

Thomas Foley

Former Speaker of the House

Warren Rudman

Former Senator from New

Hampshire

Task Force Members:

Norman Augustine

Chairman, Executive Committee,

Lockheed Martin Corp.

Jeffrey Bergner

Sr. Fellow, German Marshall Fund

of the United States

Charles Boyd

President & CEO, Business

Executives for National Security

Raymond Chambers

Chairman, Amelior Foundation

Maurice Greenberg

Chairman & CEO, American

International Group

John Hamre

Former Deputy Secretary of Defense

Robert Livingston

Former Representative from

Louisiana

Charles Robb

Untangling the Web:

Congressional Oversight and the

Department of Homeland Security

s a column of smoke rose from the Pentagon in the distance

on the late afternoon of September 11, 2001, several hundred

members of Congress assembled in unity on the steps of the

Capitol building, in a profound act of grief, solemnity, and national

resolve. We will stand together to make sure that those who have

brought forth this evil deed will pay the price, said Speaker of the

House Dennis Hastert. Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle

echoed these comments and added that the Congress would work

together to ensure that the full resources of the government are

brought to bear in these efforts.

Yet more than three years later, Congress has failed to remove a

major impediment to effective homeland security: the balkanized

and dysfunctional oversight of the Department of Homeland

Security (DHS).

While Congress worked with the executive branch to create the

Department of Homeland Security, it has done almost nothing to

match this important reorganization with a parallel initiative to put

its own house in order. Instead, it has protected prerogative and

privilege at the expense of a rational, streamlined committee

structure. The result is a Department of Homeland Security that is

hamstrung by a system of Congressional oversight that drains

departmental energy and invites managerial circumvention. Until

Congress confronts the hard task of correcting this mismatch, DHS

is at risk of failing to achieve its full potential.

Former Senator from Virginia

Frederick Smith

Chairman, President & CEO, FedEx

J.C. Watts

Former Representative from

Oklahoma

The Homeland Security Act that created DHS was the most

sweeping reorganization of the federal government since the

National Security Act of 1947 created the Department of Defense.

The new Department brought together 170,000 employees from 22

department and agencies, with the goal of overcoming bureaucratic

insularity and rivalry, and providing a single point of leadership and

responsibility for the nations efforts to defend against terrorism.

UNTANGLING THE WEB

page 2

Before the creation of DHS, no less than 88 committees and subcommittees in the House and the Senate had

responsibility for oversight of homeland security. 1 The 108th Congress took only limited steps to modify this

structure to reflect new realities. Both the House and the Senate created new subcommittees for homeland

security on their respective Committees on Appropriations. The House created a new Select Committee on

Homeland Security to serve as a focal point of attention to homeland security issues, and the Senate designated

the Government Affairs Committee as the lead committee for homeland security issues.

The changes to the Appropriations subcommittees have proven to be generally successful. The Homeland

Security Appropriations bill has been passed without undue impediments (relative to the other 12

appropriations bills) in each of its first two years. But reforms to the legislative and statutory oversight roles

of Congress for homeland security have proven to be woefully insufficient. For example, the House Sele ct

Homeland Security Committee has been a paper tiger during the 108th Congress, in spite of sincere leadership.

Many of its senior Republican members are Chairmen of other powerful committees with responsibility for

parts of DHS, and they have frequently seemed more interested in protecting their own turf than ceding power

to the new Homeland Security Committee. The Senate Governmental Affairs Committee has battled similar

vested interests in its own chamber.

The leaders of these legacy committees are sincere in their belief that they can more effectively guide the

component agencies within DHS that they have long overseen. But ultimately, this fragmentation preserves

the rivalries and cultural barriers that the creation of the Department was intended to eliminate; and it prevents

DHS from acting as a single, well-coordinated team.

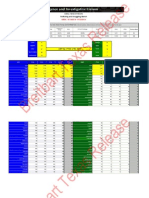

The 88 committees and subcommittees that had some amount of jurisdiction over various aspects of homeland

security prior to the creation of DHS shrunk to a mere 79 after the reorganization in the 108th Congress. 2

These lines of oversight are identified in the chart in Appendix A.

The Department of Homeland Security is still responsible to everyone which makes it accountable to

no one.

In comparison, the Department of Defense, with a budget that is more than ten times greater than DHS, reports

to only 36 committees and subcommittees in the House and the Senate. 3 Most importantly, at least 80% of

DoD oversight is concentrated in just six places: the two Armed Services committees and the Defense and

Military Construction Subcommittees on Appropriations in both chambers.

By contrast, all 100 senators and no fewer than 412 out of 435 House members currently have some degree of

oversight over DHS. The implication of this is clear: very few members of Congress have any real incentive

to acquire expertise on homeland security issues and those who do may have difficulty developing a

perspective that includes related concerns beyond their committees or subcommittees domain.

For example, the House Transportation and Infrastructure committee (T&I) and the Senate Commerce

committee have taken the lead on transportation security issues in the past three years, and have been generally

effective at guiding the creation and development of the Transportation Security Administration. But

transportation security cannot be dealt with in a vacuum; rather, it is a subset of greater homeland security

1

The Coast Guard and the Transportation Security Administration were in the Department of Transportation; the US Customs

Service and US Secret Service were in the Department of the Treasury; the Immigration and Naturalization Service was in the

Department of Justice; and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service was in the Department of Agriculture. Numerous

smaller entities were previously in a range of departments, including Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Energy, Health and Human

Services, Justice, and Treasury.

2

CSIS/BENS internal analysis, based on checks of congressional testimony database and committee websites.

3

Ibid.

UNTANGLING THE WEB

page 3

concerns, and must be addressed in conjunction with issues such as immigration and border security, critical

infrastructure protection, and privacy, among others. The current multiplicity of authority naturally leads to

isolated efforts and fragmented priorities for DHS.

This fragmentation also creates the conditions for mid-level subordinates to end-run the leadership of DHS

leadership, and appeal directly to Congressional committees with which they have long-standing relationships.

It allows outside interest groups, single issue lobbies, and government contractors to more easily find

champions for parochial interests and pork barrel projects that fall outside the strategic mandate and intent of

DHS.

Homeland security needs to be guided by a smaller set of members of Congress, who can develop longterm expertise on homeland security issues and be responsible for developing a strategic and wellinformed perspective that can guide and advise the Department.

Recent months have seen some movement on this issue in the Congress, pursuant to the 9/11 Commissions

recommendation in July 2004 to reform oversight of homeland security:

Congress should create a single, principal point of oversight and review for homeland security. Congressional

leaders are best able to judge what committee should have jurisdiction over this department and its duties. But

we believe that Congress does have the obligation to choose one in the House and one in the Senate, and that

this committee should be a permanent standing committee with a nonpartisan staff.4

Members of the Commission reiterated the importance of these recommendations in the weeks following the

release of the Commission report. Commission co-chair Lee Hamilton told Congress: you have to get your

house in order so that you can have robust oversight over the Department of Homeland Security. The

Department of Homeland Security needs your advice and counsel. And they want to be able to come, as

Secretary Ridge said to us, I want to be able to come to one body of expert members of the Congress and lay

out my problems to them, tell them what we've done, tell them what we haven't done and get their advice and

counsel. 5

Both chambers of Congress have taken steps, at least nominally, to respond to the 9/11 Commission, and

create new oversight structures for the 109th Congress. The House Select Committee on Homeland Security

has recommended that it be transformed into a permanent standing committee with clear and primary

oversight of DHS. 6 The recommendation is currently under consideration by the House Rules Committee.

Less progress was made in the Senate. In a promising start, the Senate leadership convened a task force in

August 2004, led by Senators McConnell and Reid, to make recommendations for reforming oversight in the

chamber 7. The final report was bold and appropriate, calling for a formal transformation of the Governmental

Affairs Committee into a Homeland Security Committee, with a commensurate, centralizing transfer of

authority from other committees. But vested interests rallied to dismantle this plan piece by piece; the

Governmental Affairs Committee was changed in name only, and large oversight responsibilities were

guarded by other legacy committees in the Senate.

We believe that partial reform or piecemeal efforts will be ineffective. The Department of Homeland

Security will be insufficiently accountable unless true reforms are made to place the majority of

oversight responsibility in one committee in each chamber of Congress. The current situation poses a

4

9/11 Commission Report, page 421.

Committee hearing, House Select Committee on Homeland Security, August 17, 2004

6

http://homelandsecurity.house.gov/files/reccomendationsreport.pdf

7

http://mcconnell.senate.gov/record.cfm?id=227202&start=1

5

UNTANGLING THE WEB

page 4

clear and demonstrable risk to our national security.

It is a given that the prerogatives of power and seniority will remain paramount in a Congress where members

must serve their constituents well to ensure their re-election. The Congress has been turf-conscious since the

founding days of the United States, and throughout its history committee structure has often better served the

interests of members than the interests of the people. Efforts to restructure Congress on nascent issues such as

energy and the environment in the last thirty years have proven to be difficult as a result.

But homeland security is too critical a priority to suffer for these reasons. It is time for the leadership of the

House and the Senate, with the support of the Bush administration, to move forward to support the spirit and

the letter of the 9/11 Commissions recommendation.

We recommend that both the House and the Senate create strong standing committees for homeland

security, with jurisdiction over all components of the Department of Homeland Security. We

recommend that these committees have a subcommittee structure that maps closely to the core mission

areas outlined in the National Strategy for Homeland Security, 8 not simply to the individual directorates

of DHS. Further, we recommend that these committees be established pursuant to developing a small,

expert cadre of members who can exercise oversight and craft legislation taking into account the full

spectrum of homeland security requirements not simply one narrow element of the domestic war

against terrorism.

Not long after the end of World War II, in the days of the gathering threat of Soviet communism, Congress

faced a similar challenge. World War II proved that national security and defense required a global and

unified response; but the oversight of defense activities was split between two committees in each chamber,

the Military Affairs Committee and the Naval Affairs Committee. Among other reforms, the Legislative

Reorganization Act of 1946 merged these two committees into the Armed Services Committees. These

reforms were not easy; President Truman noted how the problem of reorganizing and modernizing the

Congress has been a peculiarly difficult one. But by moving forward, Congress set the stage for clear

statutory oversight of the Department of Defense, which was created shortly thereafter in 1947. Today the

Secretary of Defense remains responsible primarily to the House and Senate Armed Services Committee, and

seldom faces demand from other committees for testimony.

The Congress faces a similar challenge today, and the imperative for change is just as important. Without

reform, the Department of Homeland Security will suffer from diffuse accountability and lack the centralized,

coordinated guidance demanded by its vast responsibilities. One clear authorizing committee in each chamber

of Congress can hold the Department accountable and ultimately improve its effectiveness in the long battle

ahead. Without this authority, DHS is at risk of becoming sluggish, distracted, or complacent, and failing to

develop the capabilities required for the front lines of the war on terror.

The people of the United States are shareholders in homeland security, and deserve the assurance that the

tens of billions of dollars of their money spent each year are in fact improving the security of the nation

and its ability to combat terrorism. But Congress is faring poorly as a board of directors on homeland

security. The committees that it has given nominal responsibility for homeland security are overpowered

by vested rivals with conflicting agendas. No large organization could operate with such disjointed

oversight. Neither can the department charged with safeguarding the security of the American homeland.

Nearly all other parts of government have reorganized to improve the nations security now it is

Congress turn to do the same, and fulfill the solemn promise made on the steps of the Capitol over three

years ago.

8

Intelligence and Warning, Border and Transportation Security, Domestic Counterterrorism, Protecting Critical Infrastructures and

Key Assets, Defending Against Catastrophic Threats, Emergency Preparedness and Response.

Banking

Commerce,

Science, &

Trans

Environ &

Public

Works

Surface Trans &

Merchant Marine

Science, Technology,

& Space

Budget

Economic Policy

Foreign

Relations

Govt Affairs

Fisheries, Wildlife, &

Water

International Ops &

Terrorism

Oversight of Govt

Mgt, Fed Work, & DC

Clean Air, Climate

Change & Nuke Safety

European Affairs

Investigations

Finance

Oceans, Fisheries, &

Coast Guard

Indian

Affairs

H.E.L.P.

Senate

Financial Mgt,

Budget, & Int Security

Communications

Crime, Corrections, &

Victims Rights

Aviation

Armed

Services

Immigration, Border

Security, & Citizenship

Secretary

Homeland Security

Approps

Dep Secretary

Leg

Affairs

Agriculture,

Nutrition, &

Forests

IAIP

EP&R

S&T

Small

Business

Small

Business

BTS

Privacy

Officer

Admin

Inf

Analys

CFO

Infra

Protect

Private

Sector

Prog,

Plans,

Budget

TSA

USCG

CBP

USSS

Select

Intelligence

Cybersecurity,

Science, & R&D

Emergency Prep &

Response

R&D

Homeland Security

Labor, HHS,

Education, & Related

Armed

Services

MGT

Public

Affairs

Commerce, Justice,

State, & Judiciary

Approps

Chief of

Staff

Executive

Secretary

Trans, Treasury, &

General Government

NCRC

HCO

OSLGCP

CIO

Citizen &

Imm Serv

Ombuds

Terror, Unconven

Threats, & Capabil

ICE

HSARPA

Sys, Eng,

& Dev

FLETC

Select

Homeland

Security

Infrastructure &

Border Security

Inspector

General

Intelligence and

Counterterrorism

Civ Rights

Civ Lib

HumInt, Analysis, &

Counterintelligence

Security

CPO

Budget

HLS

Center

Judiciary

Terrorism, Tech, &

Homeland Security

Technical & Tactical

Intelligence

Int Affairs

FEMA

CIS

Counter

Narcotics

HSAC

General

Counsel

Terrorism & Homeland

Security

Permanent

Select

Intelligence

Oversight &

Investigation

Veterans

Trade

Ways &

Means

Commerce, Trade, &

Consumer Protection

Energy &

Commerce

Health

Civil Serv & Agency

Organization

Oversight &

Investigation

Crim Justice, Drug

Policy, & Human Res

Commercial &

Administrative Law

Coast Guard &

Maritime Trans

Dom & Int Monetary

Policy, Trade, & Tech

Energy Policy, Natural

Res, & Reg Affairs

Constitution

Econ Dev, Pub Builds,

& Emergency Mgt

Financial Institutions

& Consumer Credit

Govt Efficiency &

Financial Mgt

Courts, Internet, &

Intellectual Property

Highways, Transit, &

Pipelines

Housing & Commun

Opportunity

Nat Sec, Emerging

Threats, & Int Relat

Europe

Crime, Terrorism, &

Homeland Security

Oversight &

Investigation

Tech, Info Policy, &

Intergovt Relat

Int Terror, Nonprolif, &

Human Rights

Immigration, Border

Security, & Claims

Financial

Services

Govt

Reform

Int

Relations

Judiciary

Telecommunications

& Internet

House

Aviation

Environment, Tech, &

Standards

Regulatory Reform &

Oversight

Railroads

Fish, Conservation,

Wildlife, & Oceans

Research

Rural Enterprise,

Agriculture, & Tech

Water Resources &

the Environment

Resources

Science

Small

Business

Trans &

Infrastructure

108th Congress

Briefing or

Meeting

Subcommittee

Hearing

Committee

Hearing

Subcommittee

APPENDIX A

Committee

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Recon - Core RulebookDokument46 SeitenRecon - Core RulebookJoshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Report On RF Scanning in A Shielded Environment: International Center Against Abuse of Covert TechnologiesDokument53 SeitenReport On RF Scanning in A Shielded Environment: International Center Against Abuse of Covert TechnologiesCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- DCC Free RPG Day 2008 Punjar The Tarnished Jewel (4e)Dokument17 SeitenDCC Free RPG Day 2008 Punjar The Tarnished Jewel (4e)serenity4233% (3)

- NSA Rejection LetterDokument3 SeitenNSA Rejection LetterDavid_HarrisGershonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analyst Desktop Binder - REDACTEDDokument39 SeitenAnalyst Desktop Binder - REDACTEDAndrea Stone89% (18)

- Mole EmailsDokument15 SeitenMole EmailskpoulsenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dystopia and XXTH Century Society: Orwellian and Huxleyan VisionDokument38 SeitenDystopia and XXTH Century Society: Orwellian and Huxleyan VisionAva PascalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hiding The Bodies: The Myth of The Humane Colonisation of Aboriginal Australia - Harris, JohnDokument26 SeitenHiding The Bodies: The Myth of The Humane Colonisation of Aboriginal Australia - Harris, JohngrootvaderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Common Ground Between Islam and Buddhism - Reza Shah-KazemiDokument170 SeitenCommon Ground Between Islam and Buddhism - Reza Shah-KazemiSamir Abu Samra100% (4)

- H.A.A.R.P.: High Frequency Active Auroral Research ProgramDokument14 SeitenH.A.A.R.P.: High Frequency Active Auroral Research Programflyingcuttlefish100% (1)

- WMD LewisDokument31 SeitenWMD LewisCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Senate Torture ReportDokument525 SeitenSenate Torture Reportawprokop100% (1)

- WMD LewisDokument31 SeitenWMD LewisCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- DHS Whistleblower Says War On Terror Is A CharadeDokument2 SeitenDHS Whistleblower Says War On Terror Is A CharadeCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Senate Torture ReportDokument525 SeitenSenate Torture Reportawprokop100% (1)

- Nashville Police Complains About Secret ServiceDokument8 SeitenNashville Police Complains About Secret ServiceJeffrey DunetzNoch keine Bewertungen

- DNI Statement On The Collection of Intelligence Pursuant To Section 702 of The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance ActDokument1 SeiteDNI Statement On The Collection of Intelligence Pursuant To Section 702 of The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance ActCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Senate Torture ReportDokument525 SeitenSenate Torture Reportawprokop100% (1)

- Muslim Brotherhood General Strategic Goal For North AmericaDokument32 SeitenMuslim Brotherhood General Strategic Goal For North AmericaCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2010 Nuclear Posture Review ReportDokument72 Seiten2010 Nuclear Posture Review ReportCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Washington in The Lap of RomeDokument286 SeitenWashington in The Lap of RomeThierry29100% (1)

- NCTC Watchlist Intercept 14 0723Dokument166 SeitenNCTC Watchlist Intercept 14 0723charlene zechenderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Balkan CrisisDokument16 SeitenBalkan CrisisAzhan AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Darpa Baa 14 39Dokument39 SeitenDarpa Baa 14 39CharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Function 150 & Other International Programs: Executive Budget SummaryDokument178 SeitenFunction 150 & Other International Programs: Executive Budget SummaryCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Annual Report 2010Dokument16 SeitenFinal Annual Report 2010CharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Texas Bitcoin Decision Re SECDokument4 SeitenTexas Bitcoin Decision Re SECjeff_roberts881Noch keine Bewertungen

- Darby CBP Leaked NumbersDokument18 SeitenDarby CBP Leaked NumbersBreitbartTexasNoch keine Bewertungen

- FAX Letter To Speaker of The U.S. House John Boehner The U.S. Congressman From Ohio Sent 11 Jun 2011Dokument20 SeitenFAX Letter To Speaker of The U.S. House John Boehner The U.S. Congressman From Ohio Sent 11 Jun 2011cfkerchner100% (1)

- 2014 Southcom Posture Statement Hasc Final PDFDokument46 Seiten2014 Southcom Posture Statement Hasc Final PDFCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defund Obamacare Act of 2013Dokument2 SeitenDefund Obamacare Act of 2013Senator Ted CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Three Emails - Benghazi AlertsDokument5 SeitenThree Emails - Benghazi AlertsTommy PetersNoch keine Bewertungen

- TranscriptDokument8 SeitenTranscriptCharleneCleoEibenNoch keine Bewertungen

- IRS Letter of Complaint Against Rove's Crossroads GPSDokument15 SeitenIRS Letter of Complaint Against Rove's Crossroads GPSSpandan ChakrabartiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pol Operação Condor 1Dokument14 SeitenPol Operação Condor 1Candido VolmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- DDDDDDDDDDDDDDokument11 SeitenDDDDDDDDDDDDDYassine AmalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zack Griffith - Cast Your Vote War of 1812Dokument4 SeitenZack Griffith - Cast Your Vote War of 1812api-550337892Noch keine Bewertungen

- Female Prisoners' Survival Strategies in Stalin's GulagDokument27 SeitenFemale Prisoners' Survival Strategies in Stalin's GulagSterling Fadi NasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- User Guide PDFDokument14 SeitenUser Guide PDFyuyuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.ambrose S and Martha Penny Grass Perkins CA 1869Dokument23 Seiten1.ambrose S and Martha Penny Grass Perkins CA 1869wmdangilbert1601Noch keine Bewertungen

- BIG WHITE LIE A Book by Michael Levine. 1993-2 PDFDokument2 SeitenBIG WHITE LIE A Book by Michael Levine. 1993-2 PDFVincentNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1296169172JH 011311 - WebDokument12 Seiten1296169172JH 011311 - WebCoolerAdsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comp Gov 7th EdDokument299 SeitenComp Gov 7th EdDidem ÇataltepeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 Summary BATISDokument2 SeitenChapter 1 Summary BATISSpring AndersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Belcher Bits BB-42: Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) 1/48 Belcher BitsDokument1 SeiteBelcher Bits BB-42: Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) 1/48 Belcher BitsJohn ShermanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The New York Times Current History: The European War, February, 1915 by VariousDokument225 SeitenThe New York Times Current History: The European War, February, 1915 by VariousGutenberg.orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modern Times (History) : CharacteristicsDokument5 SeitenModern Times (History) : CharacteristicsMihaela TomaNoch keine Bewertungen

- History Form Two-Topic 1Dokument6 SeitenHistory Form Two-Topic 1edwinmasaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spendler - With Lukacs in BudapestDokument5 SeitenSpendler - With Lukacs in Budapestgyorgy85Noch keine Bewertungen

- Krak Des Chevaliers - WikipediaDokument16 SeitenKrak Des Chevaliers - Wikipediabalta2arNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filipinos in Nueva Espaã A: Filipino-Mexican Relations, Mestizaje, and Identity in Colonial and Contemporary MexicoDokument29 SeitenFilipinos in Nueva Espaã A: Filipino-Mexican Relations, Mestizaje, and Identity in Colonial and Contemporary MexicoTerry LollbackNoch keine Bewertungen

- Military Standard 105dDokument76 SeitenMilitary Standard 105dYuri Jesus V.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cold War Flashcards - UpdatedDokument20 SeitenCold War Flashcards - UpdatedZackNoch keine Bewertungen

- AFES FINAL Announcement As of 14 SepDokument16 SeitenAFES FINAL Announcement As of 14 Sepvanhau24Noch keine Bewertungen

- SGWM-682-54 Eng PDPDokument3 SeitenSGWM-682-54 Eng PDPwajdi belkahlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davis-Monthan Economic Impact Analysis For 2015Dokument14 SeitenDavis-Monthan Economic Impact Analysis For 2015KOLD News 13Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Family's Billions Artfully Sheltered (November 2011)Dokument6 SeitenA Family's Billions Artfully Sheltered (November 2011)crr12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Narrative AnaylisisDokument4 SeitenNarrative Anaylisisapi-301482795Noch keine Bewertungen

- 05 - War - of - 1812 - Notes - PageDokument3 Seiten05 - War - of - 1812 - Notes - PageFrancisco Solis AilonNoch keine Bewertungen