Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

HCA322D - 2008 Bonusclaim

Hochgeladen von

pschilOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

HCA322D - 2008 Bonusclaim

Hochgeladen von

pschilCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A

HCA 322/2008

IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE

HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION

D

COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE

ACTION NO 322 OF 2008

(Transferred from LBTC 5551 of 2007)

F

____________

G

BETWEEN

TADJUDIN SUNNY

Plaintiff

and

J

BANK OF AMERICA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION Defendant

K

____________

Before: Hon To J in Court

Dates of Hearing: 8-10, 13-17, 20-24, 27-30 January 2014 and

4, 10-11 February 2014

O

Date of Judgment: 24 December 2014

______________

Q

JUDGMENT

______________

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

1.

This is an action for breach of contract of employment.

The

Plaintiff, Tadjudin, commenced her employment with Bank of America

(the Bank), as an analyst at the level of vice president on 5 June 2000.

Her contract of employment provided that either party may terminate the

F

employment by given a minimum of one months notice in writing or by

paying one months salary in lieu of notice.

The contract also provided

that the Plaintiff was eligible to be considered for a bonus under the

H

Banks performance incentive programme, subject to her being in

employment with the Bank at the time the Bank came to decide upon and

pay bonuses under the programme.

The Plaintiff received generous

bonuses for the years from 2000 through to 2006.

On 28 August 2007,

the Bank terminated the Plaintiffs employment by giving her a months

salary in lieu of notice, without any bonus or pro-rata bonus for 2007.

L

2.

The Plaintiff commenced proceedings in the Labour Tribunal

against the Bank for breach of contract and in the District Court in DCEO

N

4 of 2009 for sex discrimination under the Sex Discrimination Ordinance,

Cap 480 (SDO).

Her claim in the Labour Tribunal was transferred to

the High Court under the present action.

P

Her claim under the SDO was

stayed pending the outcome of these proceedings.

The parties claims and defence

3.

In this action, the Plaintiff claims:

U

`

(1)

damages for wrongful termination of employment by

the Bank with the intention of depriving her of the

C

performance bonus for 2007; and

(2)

damages for perverse, irrational and mala fide

evaluations of her performance bonuses for 2005, 2006

E

and 2007.

4.

G

Her claims are based on the following terms implied into her

contract of employment at common law:

(1)

The Bank shall not exercise its right to terminate her

employment by giving one months notice or by paying

I

one months salary in lieu of notice in order to avoid

her being eligible for the performance incentive

programme (the implied term of anti-avoidance).

K

(2)

The Bank should not implement its performance

evaluations in respect of the Plaintiff in an irrational,

perverse or arbitrary manner that was not bona fide.

M

(3)

The Bank should not administer its performance

incentive programme in respect of the Plaintiff in an

irrational, perverse or arbitrary manner or in a manner

O

that was not bona fide.

(4)

The Bank should not act in a manner contrary to the

implied term of mutual trust and confidence between an

Q

employer and employee (the implied term of mutual

trust and confidence).

The first three implied terms have been expressly pleaded, but not the

fourth.

The fourth implied term was raised in the Plaintiffs opening

submission, which was then extensively argued in her closing submission.

U

`

5.

The Bank disputes the existence of the first implied term.

It

accepts the second and third implied terms but disputes it was in breach.

C

It takes great exception to the fourth implied term being argued and

strongly objects to any issue being raised on this implied term, which

remains un-pleaded by the close of the Plaintiffs case.

E

The un-pleaded implied term of mutual trust and confidence

6.

The implied term of mutual trust and confidence was not

pleaded and, despite objection, remains un-pleaded by the close of the

H

Plaintiffs case.

The Plaintiffs position is that it is trite that while points

of law may be pleaded, it is not required to be pleaded under Order 18 rule

11 of the Rules of the High Court (RHC).

Mr Harris SC, leading

counsel for the Plaintiff, submits that the implied term of mutual trust and

confidence is hardly a controversial principle of law and is described in the

Encyclopedia of Employment Law as the cornerstone of all contracts of

L

employment.

He therefore argues that in circumstances where the

Plaintiff has pleaded the full terms of her employment contract, which she

has, and absence any requirement to plead matters of law under the RHC,

N

there is no need to specifically plead this implied term which is so widely

accepted as affecting all contracts of employment.

7.

The Banks objection is that by introducing the implied term

of mutual trust and confidence with the two sub-category un-pleaded

implied terms under it, the Plaintiff is introducing an entirely new and

R

different case from that which was pleaded and thus should not be allowed.

As a matter of law, the duty of mutual trust and confidence between an

T

Sweet & Maxwell at 21-1.1.

U

`

V

employer and his employee is nowadays implied into every contract of

employment.

The existence of this implied term in a contract of

employment was affirmed by the House of Lords in Mahmud v Bank of

Credit and Commerce International SA (in compulsory liquidation) 2.

3

See

also Johnson v Unisys Ltd ; and Eastwood v Magnox Electric plc .

E

Pausing here, I would agree with Mr Harris SC that there is no need to

plead such a well established principle of law for the purpose of advancing

the Plaintiffs pleaded case, such as the existence of the implied terms

G

which were pleaded.

8.

I

However, that is not what the Plaintiff seeks to achieve.

Plaintiff pleaded three implied terms.

In the opening submission, the

Plaintiff contends that the fourth implied term is free standing and distinct

from the other three which were pleaded.

The

I

In his closing submission,

Mr Harris SC is not seeking to argue that the court should allow the

Plaintiff to rely on the implied duty of trust and confidence for the purpose

of implying the terms which have been pleaded, but contends two separate

M

sub-category implied terms implied under the duty of mutual trust and

confidence which have not been pleaded, namely:

(i)

an employer must not exercise a power to dismiss

unconscionably and without reasonable cause and

contrary to the legitimate expectations of the employee;

and

Q

(ii)

must not exercise a power to dismiss to deprive an

employee of a contractual benefit which results in the

unreasonable forfeit of such a benefit.

S

S

2

3

[1998] AC 20.

[2003] 1 AC 518.

[2005] 1 AC 503

U

`

9.

These two sub-category implied terms are indeed free

standing and separate from the three pleaded implied terms.

C

They are

directed at the Plaintiffs claim for the 2007 bonus, which is covered by the

first implied term.

The Plaintiffs case under the first implied term is a

very narrow one, ie that the Bank dismissed her with the subjective

E

intention of avoiding payment of the 2007 bonus.

That is the pleaded

case which the Bank is required to meet under the statement of claim.

However, the scope of these two sub-category implied terms sought to be

G

introduced under the pretext of a well recognised duty of mutual trust and

confidence is much wider.

They expand the Plaintiffs case from

subjective intention of the Bank to avoid payment to objective

I

unconscionable dismissal, lack of reasonable cause of dismissal, legitimate

expectation of the Plaintiff, and the mere fact of unreasonable forfeit of the

bonus.

Clearly, the Plaintiff is introducing a very different case.

10.

Mr Harris SC argues that as the implied term of mutual trust

and confidence is a trite legal principle of law which need not be pleaded

M

the Bank can hardly complain about being surprised or ambushed.

Had

he not included the two sub-category implied terms, I would agree.

However, it is Mr Harris SCs submission that the two sub-category

O

implied terms are included under the umbrella of the implied term of

mutual trust and confidence.

The obligations under these sub-category

implied terms are not, as yet, established legal principles.

Q

They are just

implied terms suggested by Cabrelli in his article, Discretion, Power and

the Rationalisation of Implied Terms in Industrial Law Journal 5 to give an

employee anti avoidance protection against express terms in a contract of

S

employment which provide for certain conditional payments, the condition

5

T

Vol 36 No 2, June 2007 at 200

U

`

V

being that the employee is still in the employment of his employer at the

time of payment.

As submitted by Mr Huggins SC, leading counsel for

the Bank, the purpose of Cabrellis article is to submit that the existing law

should be conceptualized, rationalized and developed by reference to the

implied term of mutual trust and confidence.

from the approach in the United Kingdom authorities, such as Clark v

The article is one in which

an academic is proposing a development in the law which would depart

Nomura International Plc

G

and Horkulak v Cantor Fitzgerald

International 7 and has followed another author, Brodie 8 in querying the

suitability of the tests of irrationality in Clark v Nomura and Horkulak

because the irrationality test poses an extremely heavy burden on an

I

employee to satisfy.

Both Brodie and Cabrelli disagree with the approach

of Mummery LJ in Keen v Commerzbank AG 9.

These sub-category

implied terms are not established legal principles yet.

K

Cabrellis suggestion that they should be pleaded and tested in court.

11.

Indeed, it is

As Chief Justice Ma said in Kwok Chin Wing v 21 Holdings

Limited & Another 10, issues must be properly pleaded unless for some

reason the pleadings have assumed a less significant role in the

proceedings.

The Chief Justice said:

It should by now really be quite unnecessary to issue yet another

reminder on the rationale behind pleadings. The basic objective

is fairly and precisely to inform the other party or parties in the

litigation of the stance of the pleading party (in other words, that

partys case) so that proper preparation is made possible, and to

ensure that time and effort are not expended unnecessarily on

R

6

[2000] IRLR 766 (QBD)

7

[2005] ICR 402; [2004] 942

8

D Brodie, The Employment Contract: Legal Principles, Drafting, and Interpretation (Oxford: OUP,

2005) at p 200 at 11.27

9

[2007] ICR 623

10

FACV no 9 of 2012

U

`

other issues It is the pleadings that will define the issues in a

trial and dictate the course of proceedings both before and at trial.

Where witnesses are involved, it will be the pleaded issues that

define the scope of the evidence, and not the other way round.

In other words, it will not be acceptable for unpleaded issues to

be raised out of the evidence which is to be or has been

adduced

It is simply not permissible for an issue to be raised in this

way: one does not sift through the evidence adduced in a trial

in the hope that something was said that can conceivably found a

cause of action. Issues, I would reiterate, must be properly

pleaded unless for some reason the pleadings have assumed a

less significant role in the proceedings

The purpose of pleadings, in clearly and unambiguously setting

out the true extent and nature of a dispute not just for the benefit

of the parties but also for the Court in managing and trying cases,

remains important under our system of civil justice. The

retention of the old rules as to pleading as well as the

introduction of new provisions over four years ago under the

11

Civil Justice Reform, reinforce this.

12.

K

The same principle applies to contractual terms to be implied

from legal duties as matter of law.

A party may not, on the pretext of

legal argument, be allowed to wander into un-pleaded arena, leaving his

opponent pondering what case he has to meet and catching him unprepared.

M

While the existence of the duty or implied term of mutual trust and

confidence is trite law which need not be pleaded, the issue raised by such

legal principle must be pleaded.

The existence of the two sub-category

implied terms allegedly included under its umbrella is not established legal

principle.

They are facts which must be pleaded.

scope than that which was pleaded.

They are wider in

Had they been pleaded, the Bank

would have marshalled a separate set of legal arguments, adduced other

R

evidence and cross-examined on a different basis and presented its case

differently.

It would be grossly unfair and prejudicial to the Bank to

allow the two sub-category implied terms to be raised at this stage.

T

11

The

T

FACV no 9 of 2012 at 21-23.

U

`

V

Plaintiff deliberately chose not to amend her statement of claim to properly

raise and plead the two sub-category implied terms.

appropriate that she should not be allowed to rely on them.

It is only

That said, as

the duty of mutual trust and confidence is a trite principle, the above

conclusion in no way preclude the Plaintiff from arguing that the pleaded

E

terms have been implied into her contract of employment with the Bank by

reason of this legal principle, though not pleaded.

Sex discrimination issue

13.

The Plaintiff made a myriad of allegations, including one of

sex discrimination.

She commenced separate proceedings in the District

Court against the Bank seeking redress for treating her less favourably than

J

it would treat a man and for discriminating against her in relation to her

employment because she is a female.

She repeated her claims for sex

discrimination in her pleadings and in her witness statements in this action.

L

Her plea is that she was given unreasonable treatment due to a

discriminatory state of affairs within the office against female employees.

14.

While the Bank is desirous to have the sex discrimination

claims dealt with together in this action once and for all, Mr Huggins SC

queries if this court has jurisdiction to hear the Plaintiffs complaints of sex

P

discrimination, given that section 76 of the SDO requires any claims of sex

discrimination under that Ordinance be brought in the District Court and

that jurisdiction cannot, as matter of law, be conferred by consent.

R

15.

The Plaintiffs position, as explained by Mr Harris SC, is that

the allegations of sex discrimination were background only and may go to

T

the rationality or otherwise of the Banks regime at any given time.

He is

U

`

10

not inviting the court to rule or make any finding on sex discrimination but

asks the court to factor it in insofar as it relates to the attitude of the Bank.

C

With respect, I agree with Mr Huggins SC that this is a bizarre position for

the Plaintiff to adopt.

If this court is not to make any finding on sex

discrimination, I am unable to see how to factor it in when deciding the

E

rationality or otherwise of what the Plaintiff calls the Banks regime or

assessment of bonuses for the various years complained of.

16.

As analyzed above, the contractual cause of action in this

action are whether the Bank was in breach of the implied term not to

terminate the Plaintiffs employment to avoid paying her a bonus in 2007;

I

and whether the Banks administration of its performance incentive

programme and performance evaluation for the years 2005 and 2006 were

irrational, perverse and in bad faith and in breach of any implied term in

K

relation to the decision after the Plaintiff was dismissed not to award a

performance bonus in relation to the year 2007.

I do not find it necessary

to make a determination on the jurisdictional issue as the issue of sex

M

discrimination is irrelevant.

finding of rationality of the Banks scheme or assessment of the Plaintiffs

bonuses.

I therefore decline to factor that in my

In any event, the evidence does not begin to establish the

Plaintiffs allegations of sex discrimination and no suggestion of sex

discrimination of any kind was put to any of the Banks witnesses.

The issues

R

17.

The issues raised in this action are:

(1)

what is the nature of the bonus under the performance

incentive programme;

T

U

`

11

(2)

whether a term that the Bank shall not exercise its right

to terminate the Plaintiffs employment by giving one

C

months notice or by paying one months salary in lieu

of notice in order to avoid her being eligible for the

performance incentive programme is implied into the

E

Plaintiffs contract of employment with the Bank;

(3)

whether the assessment of the Plaintiffs bonuses in

2005 and 2006 were irrational, perverse, arbitrary or

G

assessed in bad faith such that no reasonable employer

could have arrived at such amounts;

(4)

I

the

Bank

terminated

the

Plaintiffs

employment in August 2007 in order to avoid her being

eligible for a performance bonus; and

(5)

K

if the Bank was in breach of contract in any of the

above aspects, the quantum of damages payable to the

Plaintiff.

whether

Except the second issue, which is a mixed issue of law and fact, the other

issues are issues of fact.

N

THE IMPLIED TERM OF ANTI-AVOIDANCE

The applicable principle

18.

The Bank accepts the second and third implied terms.

Thus,

having excluded the fourth implied term, or more precisely the two sub-

category implied terms under it, what is left in dispute is the first implied

S

term.

The principles under which a term may be implied into a contract

have been set out in BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v President,

U

`

12

Councillors and Ratepayers of the Shire of Hastings 12.

A term may only

be implied into a contract, if:

C

(1)

it is reasonable and equitable;

(2)

it is necessary to give business efficacy to the contract,

so that no term will be implied if the contract is

E

effective without it;

(3)

it is so obvious that it goes without saying;

(4)

it is capable of clear expression; and

(5)

it does not contradict any express term of the contract.

As with construction of an express term, the content of a term to be

implied depends on the factual matrix at the time of making of the contract.

19.

The Banks objections to the first implied term are that it is

inconsistent with an express term of the letter of employment; inconsistent

with the employers statutory right to terminate under sections 6 and 7 of

L

the Employment Ordinance (Cap 57); and that the duty under this implied

term should not be implied into the employment agreement at all because

the legislature had enacted a comprehensive system of employment

N

protection in Part VIA of the Employment Ordinance, it is not open to the

common law to legislate into legislated area.

The Banks arguments are

13

based on the House of Lords decision in Johnson v Unisys Ltd .

P

The relevant terms in the letter of employment

20.

By a written letter of appointment dated 19 April 2000, the

Plaintiff was employed by the Bank as a vice president in its Distress Debt

S

S

12

13

(1977) 180 CLR 266 at 283.

[2003] 1 AC 518.

U

`

13

Trading Group (ISSG) at an initial monthly salary of HK$74,519 per

month with a year-end bonus equivalent to one months salary and a

C

monthly housing allowance of HK$40,000.

21.

E

Under clause 3 of the letter of employment, upon successful

completion of the probationary period, either party may terminate the

employment by giving a minimum of one months notice in writing or by

paying one months salary in lieu of notice.

G

22.

Clause 1 of letter of employment states that the Plaintiff was

entitled to a performance bonus under the Banks performance incentive

I

programme.

That clause provides:

You will be eligible for consideration under the Banks

performance incentive programme and it will subject to you

being employed by the Bank at the time of payment.

The performance bonus under this clause is the subject matter of the

L

Plaintiffs bonus claims in this action.

The performance incentive programme

N

23.

O

By reason of clause 1 of the employment letter, eligibility to

be considered for the performance incentive programme is an express term

of the Plaintiffs employment.

Generally, the Banks employees are

informed of their individual bonus payments in January after approval of

Q

the Banks board of directors.

The Bank maintains a culture of secrecy

regarding the bonus awarded to its employees.

The employees have no

knowledge about the bonus awarded to their colleagues.

S

The Plaintiff

received substantial bonuses throughout her employment with the Bank.

U

`

14

24.

One of the expressed purposes of the programme is to

compete for business and talent.

C

The programme was administered

through a continuous performance evaluation process as outlined in the

Banks Pay for Performance presentation. The presentation consists of

fourteen pages. It explains what is pay for performance and the philosophy

E

behind it; what total compensation, ie remuneration package, comprises;

how an employees performance is evaluated; and how the bonus is

assessed.

The followings are some salient features of the programme:

(1) the Bank is committed to a pay for performance

environment in which an employees performance is a

key consideration in determining his remuneration

I

package;

(2) remuneration consists of: base salary; cash incentives, ie

bonus; and equity;

K

(3) an express philosophy of the programme is that the Bank

rewards the highest performers with the greatest rewards

through basic salary, incentives, equity and rewards and

M

recognition;

(4) managers

should

aggressively

compensate

high

performing employees;

O

(5) the guiding principles for compensation are: reward

the highest performers with the greatest reward; pay

relates directly to performance; and awards are highly

Q

differentiated based on performance;

(6) the focus is on the results the employee achieved against

his specific goals;

S

(7) performance is assessed on two criteria: (a) results

measured against the plan - the What; and (b)

U

`

15

leadership behaviour - the How; each criterion is rated

as Exceeds, Meets, and Does Not Meet; and

C

(8) total compensation is market-informed and driven by

final results of the Bank and line of business as well as

the employees performance results.

E

25.

According to this Pay for Performance presentation, the

Bank expressly commits itself to a pay for performance environment and

G

promotes a performance-based culture.

This commitment is reflected in

an email issued in January 2006 by Sydney Brown of senior management

instructing the Banks department heads across the world, including Ken

I

Schneier and Scott Gordon who were heads of the ISSG from late 2004 to

early 2007, to deliver the bonus numbers for 2005 performance year to

employees by providing references to the compensation to revenue

K

levels and the ratio for the Banks competitors and stating that the Bank

are among the highest paying companies on the street.

The email

includes various attachments, fact sheets and talking points totalling 27

M

pages.

In his email dated 3 June 2006 to the Plaintiff, Ken Schneier said:

We will bend over backwards to ensure that recognition and

comp are properly allocated.

Thus the Banks commitment to pay for performance could not have been

over-stated.

26.

The Banks commitment to pay for performance environment

is also felt by its employees.

When complaining about the size of his

bonus for the year 2004, John Liptak, the Plaintiffs manager who was

S

instrumental to her dismissal, cited a general payout ratio philosophy for

people in [their] type of work.

Ken Schneier and Scott Gordon did not

U

`

16

disagree.

Ken Schneier even confirmed that for analysts, profit and loss

generated by an analysts credits is a useful tool.

C

what he called multiple touch factor.

He also mentioned

The Pay for Performance

presentation also referred to other factors such as compensation to revenue

level in the industry and the individuals What and How rating.

But,

there is an undisputed correlation between the size of the bonus and profit

contributed by the individual.

27.

From this incentive programme, it can be seen that the major

part of an employees remuneration package is composed of performance

bonus and equity which are rewards for performance, a principle to which

I

the Bank expressly commits itself.

While there is no simple formula for

determining the amount of bonus, it is largely linked to profit contribution

of the individual employee, his line of business and the Bank as a whole

K

and the compensation data in the market.

For a performing employee, the

performance bonus is very substantial.

The base salary constitutes a

lesser fraction of his remuneration package.

M

28.

On the fact, the Plaintiff had all along been paid very

substantial bonuses.

O

annual salary, and bonus to salary ratio.

The denomination is in US

of thirteen months basic monthly salary of HK$74,519 and HK$84,730

respectively plus a monthly housing allowance of HK$40,000, converted

years.

No information is available for her salary for the other

For illustration purpose, it is assumed that the Plaintiffs annual

salary for 2001 was same as that for 2000 and her salary for 2002 to 2005

Her annual salary for 2000 and 2006 are calculated on the basis

into US currency.

S

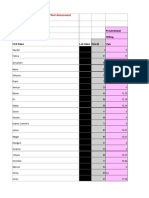

Table 1 below shows her profits contribution, her

bonus, the bonus/profit contribution percentage (bonus percentage), her

currency.

U

`

17

was the average between her salary for 2001 and 2006 as the data for those

years are not available.

The data for 2000 are not typical as the Plaintiff

C

did not work for the full year.

Table 1 Profit, bonus and salary ratios

E

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

Profits

(US$)

Bonus

(US$)

90,000

425,000

287,000

450,000

640,000

615,000

550,000

Bonus/

profit

Annual

salary

(US$)*

Bonus/

annual

salary

7.8%

7.8%

12.21%

9.00%

16.41%

7.66%

7.61%

185,737

191,738

202,755

48.46%

221.66%

No less than 6m

2.35m

5.00m

3.90m

8.03m

7.23m

G

Data not available, assessed to be 194,246

being the average for 2001 and 2006

147.75%

231.67%

329.48%

316.61%

271.26%

* On the basis of 13 months salary plus housing allowance of HK$480,000 per annum

M

29.

It can be seen from Table 1 that the Plaintiffs bonus for 2001

was more than double her annual basic salary.

Though the data for her

basic salary for 2002 through to 2006 are not available, it would not be far

O

wrong to say that her bonuses for those years were between two to three

and half times her annual salary, a very substantial part of her total

remuneration package.

In this remuneration package, the base salary is

the sauce, the performance bonus is the meat.

The nature of the bonus under the performance incentive programme

S

30.

T

It would be convenient to deal with a disputed issue as to the

nature of the performance bonus under the performance incentive

U

`

18

programme.

Mr Harris SC argues that the performance bonus is based on

performance.

An employee banks in her credits every day of the year.

At the end of the year, his bonus is assessed.

in a way which invariably produced predictable results through the

application of known principles and practices.

It is based on performance

not to use the word contractual lest the performance bonus would be

caught under Part VIA of the Employment Ordinance, under the provisions

The Banks case is that bonus is wholly discretionary, not

gratuitous and not contractual.

An employee has no entitlement to the

bonus but only to be considered for the bonus if he is still in employment

at the time when the bonus comes to be paid.

discretionary as opposed to discretionary.

31.

He calls it non-

Mr Harris SC is careful

of which the Plaintiffs claim was time barred.

G

Mr Huggins SC submits

that there is a world of difference between a legal entitlement on the one

hand and an expectation or eligibility for consideration on the other.

Though it is more likely that employees would be more motivated by a

M

contractual bonus than a mere hope of a discretionary payment which the

employer could choose in its discretion not to pay, it is not an inherent and

necessary condition of the employer/employee relationship that the

O

performance bonus would be a right and not merely a hope or expectation.

There are sound commercial reasons for an employer to provide

discretionary benefits, including bonuses, rather than guaranteed ones,

Q

particularly in the financial sector.

32.

S

Having regard to the letter of employment, the Employees

Handbook and the Pay for Performance presentation, I think the bonus to

be paid under the programme is not contractual like salary, which is

U

`

19

expressly provided by the employment agreement.

There is no expressed

amount to be paid or formula on which it is to be assessed.

C

programme is administered by the Bank.

The

The principles governing the

administration of the programme and evaluation of an employees

performance are determined by the Bank.

Performance presentation.

They are set out in the Pay for

There is no dispute that whether to award a

bonus and the amount to award is discretionary.

Given the Banks

expressed commitment to pay for performance, the very comprehensive

G

programme of performance evaluation and assessment of bonus, and the

significant ratio the performance bonus has to bear on the total

remuneration package, the discretion is not an unfettered one.

wholly discretionary as Mr Huggins SC submits.

exercised in a serious and bona fide manner.

It is not

The discretion has to be

Like the courts discretion

which has to be exercised in accordance with established legal principles,

K

the Banks discretion in awarding or not awarding as well as determining

the amount of the bonus has to be exercised in accordance with the

principles set out in the programme.

Thus,

the nature of the bonus is discretionary, not contractual or gratuitous.

However, the eligibility to be considered under the

programme is contractual, being expressly provided by clause 1 of the

letter of employment.

The discretion is not to be exercised

in an irrational, perverse or arbitrary manner that is not bona fide.

33.

If there was any breach of an implied term which

resulted in the Plaintiff being rendered ineligible to be considered under

the programme, she is entitled to such damages as will put her in the same

position as if she had been considered under the performance incentive

S

programme and awarded the bonus which would have been paid to her in

accordance with the principles of the programme.

U

`

20

Content of the implied anti avoidance term

34.

While clause 1 of the letter of employment expressly provides

that the Plaintiff is eligible for consideration for an award of the bonus

under the Banks performance incentive programme subject to her being

employed by the Bank at the time of payment, clause 3 gives the Bank the

E

right to terminate her employment without the need for justification by

giving a months notice in writing or by payment in lieu.

Thus, unless the

first implied term pleaded was implied into the employment agreement, the

G

Plaintiffs eligibility to be considered under the performance incentive

programme is illusory and could be easily taken away by the Bank

exercising its right to termination under clause 3, even if she was utterly

I

without fault.

J

35.

The ISSG, operated in a highly competitive environment in

which performance bonus was a major part of the employees total

L

remuneration package.

It is the meat of his remuneration package,

being between two to three and half times his annual base salary plus

M

allowance.

N

The bonus is not gratuitous.

performance.

It has to be earned by

The employee earns by banking in credits for profit

earned for the Bank to be paid out to him on bonus day.

An employee

therefore has a reasonable expectation to receive his bonus at the end of the

P

year.

That must also be the common understanding or expectation of the

employee and the employer because one express purpose of the

Q

performance incentive programme is to compete for talent so as to better

R

enable the Bank to compete for business in the market.

It gives an

employee the incentive to perform so as to maximise profit for the Bank by

S

linking the performance of the individual employee to the amount of the

T

bonus payment.

No talent would stay if he is under the constant fear that

U

`

21

his employer would deprive him of the fruits of his effort by terminating

him before the date of payment of the bonus.

suffer.

E

Without that the assurance

given by the implied term, the purpose of the programme would be

defeated.

The Bank would be unable to retain talent and profit would

That would be contrary to the interest of the Bank.

Not only is

the implied term not inconsistent with clause 3, it supplements the express

terms, without which the employment agreement would have no business

efficacy.

G

36.

Furthermore, an employer/employee relationship is built on

mutual trust and confidence.

I

An employer is under an implied duty to deal with his employees fairly

Thus, if at the time the Plaintiff was entering into the

K

employment agreement with the Bank she had asked,

What about my bonus if I am dismissed through no fault of my

own during the year, by notice or payment in lieu?

There is no dispute that the obligation of

mutual trust and confidence is implied into any contract of employment.

and in good faith.

An officious bystander knowing of the performance incentive programme

and clause 1 and clause 3 of the letter of employment would have readily

responded saying:

O

Surely your employer will act in good faith. It goes without

saying that he wont do that to deprive you of your bonus unless

he has good reasons to terminate your employment.

Such an answer certainly covers the implied anti-avoidance term.

implied term is obvious and it goes without saying.

clear expression.

The

It is also capable of

It may even be wide enough to cover the un-pleaded

sub-category implied terms.

U

`

22

37.

Mr Huggins SC objects to the implied term on the ground that

it is inconsistent with the express term in clause 3 of the letter of

C

employment.

Clause 3 gives the Bank not merely a power to terminate

but a lawful right to terminate at any time by notice or payment in lieu

with or without identifying any reason or cause.

He argues that it would

be inconsistent to say in one breath that there was an express lawful right

to terminate in this manner, that such termination was lawfully valid and

effective; and in the next breath to say that to terminate in this manner

G

would be wrongful, if done with an unfair intention to prevent the Plaintiff

from fulfilling the express contractual condition for consideration for the

2007 bonus.

He refers me to the first instance judgment in Thomas

Vincent v South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd 14 in which Deputy

High Court Judge Muttrie held that the implied duty of mutual trust and

confidence could not prevent the employer from terminating the

K

employment of the employee in accordance with an express term in the

contract allowing either party to terminate by giving one months notice.

38.

With respect, this approach of mechanically comparing the

implied term with express term is inappropriate in construing a contract of

employment.

context.

Each contract has to be construed in its proper factual

The factual context of that case is different from that of the

present case (see paragraph 45 below).

Mr Huggins SCs argument loses

sight of the employers overarching obligation implied by law as an

Q

incident of the contract of employment.

An employer has a duty imposed

by law to deal with his employee in good faith.

Under that duty, he may

not exercise his express contractual rights so as to destroy or seriously

S

damage this relationship of trust and confidence.

14

To say the minimum,

T

[2002] 2 HKC 353.

U

`

V

23

he may not exercise his right to terminate employment by giving notice or

payment in lieu with the intention to avoid paying the employee the

C

performance bonus.

Similar arguments had been considered by Lord

Steyn in Johnson v Unisys15.

Although that was a dissenting judgment on

the issue of legislative intent, Lord Steyns finding that a similar term as

E

the one sought to be implied did not conflict with express term of

termination by notice remains valid.

In Johnson v Unisys, counsel for the

employer relying on the notice provision argued that the obligation of

G

mutual trust and confidence could not be implied into the contract as it

conflicted with express terms of the contract.

Lord Steyn disagreed and

held that the duty could co-exist with the express term.

I

His argument approached the matter as if one was dealing with

the question whether a term can be implied in fact in the light of

the express terms of the contract. This submission loses sight of

the particular nature of the implied obligation of mutual trust and

confidence. It is not a term implied in fact. It is an overarching

obligation implied by law as an incident of the contract of

employment. It can also be described as a legal duty imposed

by law: Treitel, The Law of Contract, p 190. It requires at least

express words or a necessary implication to displace it or to cut

down its scope. Prima facie it must be read consistently with

the express terms of the contract. This emerges from the seminal

judgment of Sir Nicolas Browne-Wilkinson V-C in Imperial

Group Pension Trust Ltd v Imperial Tobacco Ltd [1991]1 WLR

589. It related to an employers express contractual right to

refuse amendments under a pension scheme.

The ViceChancellor held that the employers express rights were subject

to the implied obligation that they should not be exercised so as

to destroy or seriously damage the relationship of trust and

confidence between the company and its employees and former

employees. The employers blanket refusal was unlawful. The

decision did not involve trust law and the employer was not

treated as a fiduciary. It was decided on principles of contract

law. Sir Nicolas Browne-Wilkinson V-C described the implied

obligation of trust and confidence as the implied obligation of

good faith. It could also be described as an employers

15

He said at

paragraph 24:

T

[2003] 1 AC 518

U

`

V

24

obligation of fair dealing. In the same way an employers

express right to transfer an employee may be qualified by the

obligation of mutual trust and confidence : see United Bank Ltd v

Akhtar [1989] IRLR 507, Sweet & Maxwells Encyclopaedia of

Employment Law, vol 1, paras 1.5101 and 1.5107. The

interaction of the implied obligation of trust and confidence and

express terms of the contract can be compared with the

relationship between duties of good faith or fair dealing with the

express terms of notice in a contract. They can live together.

In any event, the argument of counsel for the employers misses

the real point. The notice provision in the contract is valid and

effective. Nobody suggests the contrary. On the other hand, the

employer may become liable in damages if he acts in breach of

the independent implied obligation by dismissing the employee

in a harsh and humiliating manner. There is no conflict between

the express and implied terms. I would therefore dismiss this

argument.

39.

Lord Hoffmann did not disagree with the above proposition.

He said at paragraphs 42 and 43:

J

42. My Lords, in the face of this express provision that

Unisys was entitled to terminate Mr Johnsons employment on

four weeks notice without any reason, I think it is very difficult

to imply a term that the company should not do so except for

some good cause and after giving him a reasonable opportunity

to demonstrate that no such cause existed.

43. On the other hand, I do not say that there is nothing which,

consistently with such an express term, judicial creativity could

do to provide a remedy in a case like this. In Wallace v United

Grain Growers Ltd 152 DLR (4th) 1, 44-48, McLachlin J (in a

minority judgment) said that the courts could imply an obligation

to exercise the power of dismissal in good faith. That did not

mean that the employer could not dismiss without cause. The

contract entitled him to do so. But in so doing, he should be

honest with the employee and refrain from untruthful, unfair or

insensitive conduct. He should recognise that an employee

losing his or her job was exceptionally vulnerable and behave

accordingly. For breach of this implied obligation, McLachlin J

would have awarded the employee, who had been dismissed in

brutal circumstances, damages for mental distress and loss of

reputation and prestige.

While saying it would be very difficult to imply such a term in the light of

the express termination provision, Lord Hoffmann did not rule out such a

U

`

25

possibility in an appropriate case.

In Canada, it was held that the courts

could imply an obligation to exercise the power of dismissal only in good

C

faith.

40.

E

In the circumstances of the Plaintiffs employment agreement,

in particular, the structure of the remuneration package, the Banks

commitment to pay for performance, and the lack of efficacy without the

implied term, I think the implied term pleaded may reasonably be implied

G

into the employment agreement and there is no inconsistency between it

and clause 3 of the letter of employment.

41.

of by the Court of Appeal in Tadjudin v Bank of America National

Association

16

Stone J said at paragraph 58:

58. Second, although it was submitted by the defendant that an

implied term must not contradict other express terms in a

contract, and in the present case, it is said that the implied term

contended for by the plaintiff is inconsistent with the express

right of termination set out in clause 3 of the Employment

Agreement, this argument of the defendant is met by the response

of the plaintiff that the plaintiff does not dispute the defendants

right to terminate her employment by notice under clause 3, or

the validity of that dismissal. The anti-avoidance term only

protects against tactics calculated to avoid the payment of the

performance bonus. In that sense therefore it is not inconsistent

with or contradicts the express term in clause 3. In this respect,

therefore, the present case can be distinguished from Johnson v

Unisys where the implied term contended for was said to be

protective of the employees interest in remaining employed.

59. Furthermore, as was said in the judgment in Takacs case, in

which there was in the contract an express provision allowing the

employers to terminate the contract at any time on four weeks

notice, at page 419 :

16

when allowing the Plaintiffs appeal against an order to

strike out this implied term.

Furthermore, Mr Huggins SCs argument had been disposed

T

[2010] 3 HKLRD 417 at 58 and 59.

U

`

V

26

I accept the claimants submission that the alleged implied term

could co-exist with the express termination provision in the

contract and that the present circumstances are distinguishable

from Johnson v Unisys. It is further, in my view, distinguishable

from Reda v Flag because in that case there was a clear and

unambiguous express right to terminate the contract at any time

without cause. There is, I conclude, a real prospect of

successfully arguing that such an implied term would supplement,

rather than be inconsistent with, the express terms of the

contract

42.

Mr Huggins SC argues that in that appeal the Court of Appeal

was considering an appeal against striking out the implied term and

decided that it was inappropriate to strike out the plea in what is a

H

developing area of law without first establishing the full factual matrix at

trial.

Hence, he submits that the above dicta are not binding on me.

43.

I respectfully disagree.

In the above dicta, the Court of

Appeal was precisely determining this narrow issue, whether the term,

assuming it is to be implied, is inconsistent with the express terms.

inconsistent, the pleading should be struck out.

If it is

Only if it is not

inconsistent that the issue should proceed to trial to have the disputed

matters resolved and a finding to be made whether the term is to be

N

implied.

O

Stone J also referred to Takacs v Barclays Services Jersey Ltd 17,

although that was only a case of striking out pleading by a master.

In that

case, Master Fontaine reached the same conclusion that a similar implied

P

term could co-exist with express termination provision in the contract.

Q

have made adequate finding of fact to enable me to find that the pleaded

term may be implied into the Plaintiffs employment agreement.

respectfully agree with and adopt the dicta of Stone J, which in any event

S

is also binding on me.

17

For similar reasons as stated by the Court of

T

[2006] IRLR 877

U

`

V

27

Appeal, I consider the implied anti-avoidance term not inconsistent with

the express term in the employment agreement.

C

44.

As for Thomas Vincent v SCMP, the argument was whether

the implied obligation of mutual trust and confidence required consultation

E

and warning before dismissal.

that obligation could not prevent the termination in accordance with an

express term.

It was on that basis that the court held that

The obligation implied in that case is different from that in

the present case.

Whether the implied obligation could co-exist with the

express term had not been argued.

In any event, that decision is not

binding on me and cannot stand well in the light of the dicta of Stone J

I

quoted above.

I prefer to follow the decision of the Court of Appeal.

45.

K

Mr Huggins SC submits that it could not be sensibly argued

that the express term in clause 1 as to the bonus and clause 3 as to

termination should be construed together so as to prevent an employer,

who decides that the conduct of an employee is such that he is not working

M

well with his team mates or whose conduct and attitude is not conducive to

the smooth operation of the business, from exercising a right to terminate

by notice or payment in lieu.

pleaded goes that far.

The implied term as pleaded is very narrow.

It

only prevents the Bank from terminating the employment with the

It does not prevent the Bank from

terminating for reasons other than to avoid paying the bonus, such as those

suggested by Mr Huggins SC.

I do not think the effect of the implied term

intention to avoid paying bonus.

Q

U

`

28

Inconsistency with statutory right under sections 6 and 7

46.

Mr Huggins SC argues that sections 6 and 7 of the

Employment Ordinance give an employer an unqualified and free standing

right to terminate the employment of his employee by notice or payment in

lieu.

But, the effect of the term sought to be implied would render it

wrongful for the Bank to terminate prior to the time for consideration and

payment of any bonus, if done with an intention to deprive the Plaintiff of

the bonus. It must follow that the implied term would effectively disentitle

G

the Bank as employer from doing lawfully and rightfully that which the

express terms of the employment agreement and sections 6 and 7 say it is

entitled to do.

He therefore submits that such a term could not be implied

into the employment agreement as it is inconsistent with sections 6 and 7.

J

47.

K

Mr Huggins SC refers me to the case of Sun Zhongguo v BOC

Group Ltd 18 in support of his proposition that sections 6 and 7 confer upon

the employer an unrestricted statutory right to dismiss upon the following

of the requisite procedure, and that there should be no implied term which

M

undermines that clear statutory right.

N

He says that Sun Zhongguo was

followed by other judges in the court of first instance, such as Yung Mei

Chun Jessi v Merrill Lynch (Asia Pacific) 19 and Kwan Hung Sang Francis

O

v HK Exchanges and Clearing Ltd 20.

48.

With the greatest respect, I am unable to read Sun Zhongguo

in the way counsel does.

R

In that case, the contract of employment

provided four methods of termination, including giving six months notice

S

18

19

20

[2003] 2 HKC 239.

[2012] HKCU 99.

[2012] 1 HKLRD 546.

U

`

29

and payment in lieu.

The plaintiffs employment was terminated partially

by notice and payment in lieu in respect of the balance of the notice period.

C

The plaintiff argued that under an implied term he was entitled to work out

the entire notice period and be paid all allowances and benefits he would

be entitled had he worked out the entire notice period so that he could earn

E

the allowances and benefits.

In rejecting that argument, the learned

Recorder said 21:

12. The Plaintiff's contention in effect was that there

should be terms implied in the agreement which abrogated the

defendants rights under section 7 of the Employment Ordinance.

It is trite law that terms could not be implied into a contract

simply because they are reasonable and no terms could be

implied if it is against an express term of the contract. In the

present case, although the power to terminate under sections 6 &

7 of the Employment Ordinance is not an express term of the

employment contract, yet the rights given are nevertheless rights

which the defendant would be entitled to enjoy unless they are

taken away by the terms of the agreement. It is difficult to see

why as a matter of business efficacy, there must be a term to

exclude the Defendants statutory rights under sections 6 & 7, nor

could I see any reason for saying that as a matter of unexpressed

common intention, there must be a term that the defendant is not

to exercise the rights given to it as employer under the two

sections.

(My emphasis underlined)

N

49.

O

Two points ought to be noted.

employers statutory right to terminate under sections 6 and 7, the learned

Recorder unequivocally acknowledged that that right could be taken away

by the terms of the agreement.

undermine.

Second, the learned Recorder then went on to explore the

He held that such a term could not be implied

because of lack of business efficacy or because it was not the parties

21

That is far from saying that it is a

sacrosanct right which no terms of a contract of employment could

pleaded implied term.

S

First, while recognising the

T

At 12

U

`

V

30

unexpressed common intention, ie that such a term is not so obvious that

it goes without saying.

Elsewhere, the learned Recorder said that an

implied term could not exclude the statutory power to terminate under

sections 6 and 7 of the Employment Ordinance.

But that was said in the

above context that a term which had no business efficacy and was not the

E

unexpressed common intention of the parties could not be implied to

abrogate a statutory right.

Nowhere did the learned Recorder express the

view that an implied term may not exclude a statutory right or have the

G

effect of suspending it.

I agree with the learned Recorder in the way I

read his judgment, but not the way Mr Huggins SC reads it.

50.

Nor do I think the other two cases quoted by Mr Huggins SC

support the alleged principle in Sun Zhongguo.

In Yung Mei Chun Jessi v

Merrill Lynch (Asia Pacific), the applicants contract of employment

K

provided for a notice period of seven days and an undertaking that she

would not, for a period of three months from the date the notice (the

restricted period), solicit the account of any of the employers clients

M

whom she had serviced.

The applicants employment was terminated

with seven days wages in lieu of notice.

She claimed wages for the

restricted period and underpayment due to currency exchange difference.

O

Her claim was dismissed by the Labour Tribunal and she sought leave to

appeal from the Court of First Instance.

the reason for her dismissal.

One of her arguments was about

She said at paragraphs15-16:

15. It was to cover up its wrongdoings that the defendant

terminated the employment and made up excuses for the

termination.

It was in that context that Deputy High

Court Judge Au-Yeung, as she then was, sought to rely on Sun Zhongguo.

U

`

31

16. The applicant was dismissed by payment of wages in lieu

of notice, which an employer had a right to do under sections 6

and 7 of the Employment Ordinance and could do so even if he

did it for an ulterior motive. When exercising the statutory right

to terminate, neither party was required to give reasons for

termination. See Sun Zhongguo v. BOC Group [2003] 2 HKC

239, Recorder Edward Chan SC. There was therefore no need

to investigate the reasons for termination. There was also

nothing to correlate the contents of the report to the alleged oral

agreements.

(My emphasis underlined)

It was not a case of conflict between an implied term and statutory right of

G

dismissal. Sun Zhongguo was relied on as authority for the proposition that

there was no need to give reasons for termination under sections 6 and 7.

51.

In Kwan Hung Sang Francis v HK Exchanges and Clearing

Ltd 22, the plaintiffs contract of employment provided for termination by

four months notice or payment in lieu.

On 3 March 2004, he accepted

the terms of a forced resignation and reserved his rights.

Then, he turned

around and alleged that he was constructively dismissed.

One of his

grounds of claim was that but for the dismissal his employer would have

M

followed the procedure for disciplinary action under the terms of his

employment which would result in no finding of any cause of complaint

against him and such process would have taken over twelve months to

O

completion by which time he would have been entitled to some option

benefits.

At the hearing, the plaintiffs counsel confirmed not to take the

point that the employer failed to follow the procedure for disciplinary

Q

action.

It was in that context that Deputy High Court Judge Au-Yeung,

as she then was, said that the statutory right to termination could not be cut

down by an implied term in the contract.

To the extent that is a statement

of law, it was not argued but conceded; and in any event obiter.

T

22

[2012] 1 HKLRD 546.

U

`

V

32

52.

The learned deputy judge then went on to hold, relying on

Sun Zhongguo, that that was so even if the employer had acted for an

C

ulterior motive. On my analysis, the issue of law decided in Sun Zhongguo

is that the statutory right could be taken away by the terms of the contract,

though on the facts of that case, a term to that effect was incapable of

E

being implied into the contract.

Insofar as the learned deputy judge was

relying on Sun Zhongguo as the authority for the proposition that the

statutory right to termination could not be cut down by the terms of the

G

contract, she was, with respect, misled.

53.

I

In my view, the right given by sections 6 or 7 is not

mandatory but permissive.

It does not require every contract of

employment to be terminated by notice or payment in lieu.

Nor does it

keep alive any contract which has not been terminated in accordance with

K

sections 6 or 7.

The statutory right to terminate by notice may

unilaterally or by agreement be waived by the party to whom it is

conferred against whom the obligation is owed.

Notice may be waived

and the parties may also be mutually discharged from the contract by

mutual agreement.

A convenient example is the form of notice.

Section

6(1) provides that a party may terminate the contract of employment by

O

giving notice to the other party, orally or in writing, of his intention to do

so.

The parties may by agreement cut down the statutory right by

waiving the right to give oral notice by agreeing that notice shall be in

Q

writing and that oral notice shall be ineffective.

An employer may also

unilaterally waive his right to terminate by giving oral notice by providing

in the contract that termination by the employer shall be by written notice

S

only whereas an employee may terminate by giving oral or written notice.

Given the principle of freedom of contract, I agree with Recorder Chan SC

U

`

33

that the statutory right to termination by notice could be taken away by the

terms of the contract of employment, express or implied.

C

54.

Accordingly, it was open to the parties to agree that the Bank

shall not exercise its right to terminate the Plaintiffs employment by

E

giving notice or payment in lieu, whether in accordance with the letter of

employment or pursuant to the statutory right under sections 6 and 7.

If

such a term was not made an express term of the employment agreement, it

G

may be implied.

Whether such an implied duty is excluded by the protection under Part VIA

I

55.

J

It is Mr Huggins SCs submission that having regard to

sections 6 and 7, which give parties to an employment contract an

unqualified right to terminate by notice or payment in lieu, and Part VIA of

the Employment Ordinance, which provides certain statutory protection to

L

employees who are thus dismissed, it is to be inferred that the legislature

did not intend to provide remedies flowing from the manner in which an

employee is dismissed, and/or for dismissal with an underlying intention to

N

avoid an employee being considered for a bonus.

The legislatures

intention is that an employee would only be protected if the underlying

intention was to extinguish or reduce a right, benefit or protection

P

conferred upon the employee by the Employment Ordinance itself.

protection under Part VIA is exhaustive.

The

If the Plaintiffs case is that her

right to the 2007 bonus was such a right or benefit, she could and should

R

have availed herself of the protection of Part VIA within the statutory

limitation period.

She did not do so and, in any event, such a claim is

now time-barred.

If her right to the 2007 bonus was not such a right, she

has no remedy.

The remedy available to her is limited by Part VIA.

U

`

34

56.

The basis for the inference drawn by Mr Huggins SC is

derived from the House of Lords decision in Johnson v Unisys.

C

In that

case, the House of Lords, by a four to one majority (Lords Bingham,

Nicholls, Hoffmann and Millett with Lord Steyn dissenting on this point),

held that an implied term that the employer would not, without reasonable

E

and proper cause, conduct itself in a manner calculated and likely to

destroy or seriously damage the relationship of trust and confidence

between the employer and employee did not exist because the evident

G

intention of the Parliament manifested in Part X of the Employment Rights

Act 1996 was that such claims had to go through specialist tribunals and

that the remedies were limited by legislature.

The rationale for this

principle is that in legislating for employment protection, the legislature

has struck a balance between the conflicting interests of employers and

employees and it is not for the court to legislate or upset this balance

K

through development of the common.

At paragraph 37 of Johnson v

Unisys, Lord Hoffmann said:

37. judges, in developing the law, must have regard to the

policies expressed by Parliament in legislation. Employment

law requires a balancing of the interests of employers and

employees, with proper regard not only to the individual dignity

and worth of the employees but also to the general economic

interest. Subject to observance of fundamental human rights,

the point at which this balance should be struck is a matter for

democratic decision. The development of the common law by

the judges plays a subsidiary role. Their traditional function is

to adapt and modernise the common law.

But such

developments must be consistent with legislative policy as

expressed in statutes. The courts may proceed in harmony with

Parliament but there should be no discord.

57.

S

Thus, Mr Huggins SC argues, likewise in the light of the

express statutory regime in Part VIA of the Employment Ordinance, which

provides for limited protection and relief to employees whose employers

U

`

35

terminate their employment with an intention to extinguish or reduce any

right, benefit or protection conferred by the Employment Ordinance or

C

payment under the employees contract, there is no room for any

contractual common law implied term as contended for by the Plaintiff.

He quotes sections 32A, 32K, 32M, 32N and 32O in Part VIA.

The

legislature has carried out that exercise of balancing the interests of

employers and employees with proper regard not only to the individual

dignity and worth of the employees but also to the general economic

G

interest in Hong Kong.

prohibition against any other forms of unfair, unjust or unreasonable

dismissal.

It is inappropriate for the court to imply any

gone far enough or has provided inadequate protection in relation to unfair

or unreasonable dismissals and to substitute its own view as to what would

paragraph 13 in support of the above proposition:

It is not for the courts to extend further a common law implied

term when this would depart significantly from the balance set by

the legislature. To treat the statutory code as prescribing a floor

and not a ceiling would do just that.

He quotes the

following dicta of Lord Nicholls in Eastwood v Magnox Electric plc 23 in

It is not for the judiciary to say that the legislature has not

be socially just and fair balance of the relevant interest.

K

Lord Nicholls said further in paragraph 14:

O

I recognise that, by establishing a statutory code for unfair

dismissal, Parliament did not evince an intention to circumscribe

an employees rights in respect of wrongful dismissal. But

Parliament has occupied the field relating to unfair dismissal. It

is not for the courts now to expand a common law principle into

the same field and produce an inconsistent outcome.

58.

S

Mr Huggins SC also refers to Lord Hoffmanns dicta in

paragraph 58 of Johnson v Unisys which is to the same effect:

23

T

[2005] 1 AC 503 at 13

U

`

V

36

59.

For the judiciary to construct a general common law remedy for

unfair circumstances attending dismissal would be to go contrary

to the evident intention of Parliament that there should be such a

remedy but that it should be limited in application and extent.

These are very powerful dicta from the highest court in the

United Kingdom, which certainly commands my respect. Mr Huggins SC

E

submits that it is no answer to these dicta to say that the statutory regime

F

under Part VIA of the Employment Ordinance is not as extensive or

comprehensive as that in the United Kingdom.

The difference is only a

matter of degree.

H

The principle is the same, namely that the legislature in

each jurisdiction has decided upon what relief should be given in the

employment field in relation to unfair dismissals and in particular in cases

I

where an employer dismisses with an underlying intention to reduce or

J

extinguish an employees right or benefits.

In Hong Kong, the deliberate

choice was made to limit protection to cases where the underlying

K

intention is to reduce or extinguish an employees rights, benefits or

L

protection conferred by the Employment Ordinance, and not otherwise.

60.

I would agree with that submission, if I am comparing like

with like.

But, I cannot lose sight of the fact that in the United Kingdom,

the Employment Rights Act 1996 provides a very comprehensive statutory

O

regime of employment protection against unfair dismissal which is far

P

more extensive than Part VIA of our Employment Ordinance.

The

interest which is protected by the United Kingdom regime is one against

unfair dismissal, whereas the interest protected by our regime under

R

Part VIA is at best an interest against dismissal to save costs, for want of

a better description.

The marked difference between the two regimes can

be demonstrated by comparing section 98 of the Employment Rights Act

T

1996 with section 32A of the Employment Ordinance.

U

`

37

61.

Section 98 of the Employment Rights Act 1996 provides :

(1) In determining for the purposes of this Part whether the

dismissal of an employee is fair or unfair, it is for the employer to

show

(a)

the reason (or, if more than one, the principal reason) for

the dismissal, and

(b)

that it is either a reason falling within subsection (2) or

some other substantial reason of a kind such as to justify the

dismissal of an employee holding the position which the

employee held.

(2)

A reason falls within this subsection if it

(a)

relates to the capability or qualifications of the employee

for performing work of the kind which he was employed by the

employer to do,

(b)

relates to the conduct of the employee,

(c)

is that the employee was redundant, or

(d)

is that the employee could not continue to work in the

position which he held without contravention (either on his part

or on that of his employer) of a duty or restriction imposed by or

under an enactment.

(3)

In subsection (2)(a)

(a)

capability, in relation to an employee, means his

capability assessed by reference to skill, aptitude, health or any

other physical or mental quality, and

(b)

qualifications, in relation to an employee, means any

degree, diploma or other academic, technical or professional

qualification relevant to the position which he held.

(4)

Where the employer has fulfilled the requirements of

subsection (1), the determination of the question whether the

dismissal is fair or unfair (having regard to the reason shown by

the employer)

(a)

depends on whether in the circumstances (including the

size and administrative resources of the employers undertaking)

the employer acted reasonably or unreasonably in treating it as a

sufficient reason for dismissing the employee, and

(b)

shall be determined in accordance with equity and the

substantial merits of the case.

U

`

38

62.

The United Kingdom regime offers a two-stage protection.

First, under section 98(1), the employer bears the burden of showing that

C

the dismissal was for one of the four reasons falling within section 98(2) or

a substantial reason.

Second, if the employer fulfilled the requirements of

section 98(1), the court shall determine whether the dismissal was fair or

E

unfair having regard to the reason shown by the employer and the

circumstances set out in section 98(4).

63.

It only protects against dismissal for reason of saving costs.

The relevant provisions are section 32A, 32K, 32L, 32M and 32O.

I

By way of contrast, the protection given under Part VIA is

very narrow.

These

I

sections provide:

32A(1) An employee may be granted remedies against his

employer under this Part

(a)

where he has been employed under a continuous contract

for a period of not less than 24 months ending with the relevant

date and he is dismissed by the employer because the employer

intends to extinguish or reduce any right, benefit or protection

conferred or to be conferred upon the employee by this

Ordinance;

(2)

For the purposes of subsection (1)(a), an employee who

has been dismissed by the employer shall, unless a valid reason is

shown for that dismissal within the meaning of section 32K, be

taken to have been so dismissed because the employer intends to

extinguish or reduce any right, benefit or protection conferred or

to be conferred upon the employee by this Ordinance.

(3)

Q

32K For the purposes of this Part, it shall be a valid reason for

the employer to show that the dismissal of the employee or the

variation of the terms of the contract of employment with the

employee was by the reason of

(a)

T

the conduct of the employee;

T

U

`

39

(b)

the capability or qualifications of the employee for

performing work of the kind which he was employed by the

employer to do;

(c)

the redundancy of the employee or other genuine

operational requirements of the business of the employer;

(d)

the fact that the employee or the employer or both of them

would, in relation to the employment, be in contravention of the

law, if the employee were to continue in the employment of the

employer or, were to so continue without that variation of the

terms of his contract of employment; or

(e)

any other reason of substance, which, in the opinion of the

court or the Labour Tribunal, was sufficient cause to warrant the

dismissal of the employee or the variation of the terms of that

contract of employment.

32L(1)

On a claim for remedies under this Part, in

determining whether or not an employer has shown that he has a

valid reason for the dismissal of an employee or for the variation

of the terms of the contract of employment with an employee

within the meaning of section 32K, the court or the Labour