Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Lit 3 Smoking Cessation

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous 8rsxG4Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Lit 3 Smoking Cessation

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous 8rsxG4Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Document downloaded from http://www.revespcardiol.org, day 17/08/2014. This copy is for personal use.

Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited.

ISCHEMIC

HEART DISEASE

Smoking Cessation and Risk of Myocardial Reinfarction in Coronary

Patients: a Nested Case-Control Study

Manuel Serranoa,b, Edurne Madozb, Isabel Ezpeletab, Beatriz San Julinb, Carlos Amzquetab,

Jos Antonio Prez Marcob and Jokin de Iralaa

a

Departamento de Epidemiologa y Salud Pblica, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Navarra

Pamplona. bAtencin Primaria. Servicio Navarro de Salud, Pamplona, Spain

Introduction and objectives. Smoking cessation reduces mortality in coronary patients. The aim of this study

was to estimate association measures between the risk of

occurrence of fatal or non-fatal reinfarction in patients

who either continue to smoke or stop after a first infarction and are treated with secondary prevention measures.

Patients and method. The study was a case-control

(1:1) design nested in a cohort of 985 coronary patients

under the age of 76 years who were not treated with invasive procedures and survived more than 6 months after

the first acute myocardial infarction. Cases were all patients who suffered reinfarction (n = 137) between 1997

and 2000. A control patient was matched with each case

by gender, age, hospital, interviewer, and the secondary

prevention timeframe.

Results. Patiehts who smoke after the first acute myocardial infarction had an odds ratio (OR) of 2.83 (95% CI,

1.47-5.47) for a new acute myocardial infarction.

Adjustment for lifestyle, drug treatment, and risk factors

(family history of coronary disease, high blood pressure,

hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes mellitus) did not

change the OR (2.80 [95% CI, 1.35-5.80]). Patients who

quit smoking had an adjusted OR of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.471.71) compared with non-smokers before the first acute

myocardial infarction. Continued smoking had an adjusted OR of 2.90 (95% CI, 1.35-6.20) compared to quitting

after the first acute myocardial infarction.

Conclusion. The risk of acute myocardial infarctions is

three times higher in patients who continue to smoke after

an acute coronary event compared with patients who quit.

The risk of reinfarction in patients who stop smoking is similar to the risk of non-smokers before the first infarction.

Key words: Myocardial infarction. Prevention. Coronary

disease. Smoking. Lifestyle.

Full English text available at: www.revespcardiol.org

Financed by a grant of the Departamento de Salud del Gobierno de

Navarra, 1998.

Abandono del tabaco y riesgo de nuevo infarto en

pacientes coronarios: estudio de casos y controles

anidado

Introduccin y objetivos. Dejar de fumar reduce la

mortalidad en pacientes coronarios. El objetivo de esta

investigacin fue estimar las medidas de asociacin entre

la aparicin de un reinfarto fatal o no fatal y el mantenimiento o el abandono del hbito tabquico tras un primer

infarto, en pacientes sometidos a medidas de prevencin

secundaria.

Pacientes y mtodo. Estudio de casos y controles

(1:1) anidados en una cohorte de 985 pacientes coronarios, menores de 76 aos, no tratados con procedimientos invasivos o quirrgicos, que sobrevivieron ms de 6

meses tras el primer infarto. Los casos (n = 137) fueron

todos los pacientes con un reinfarto entre 1997 y 2002,

emparejados con los controles por sexo, edad, hospital,

entrevistador y tiempo de prevencin secundaria.

Resultados. El hbito de fumar despus del primer IAM

present una odds ratio (OR) de 2,83 (intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%, 1,47-5,47) para un nuevo IAM. El

ajuste del modelo por otros estilos de vida, tratamientos

farmacolgicos y factores de riesgo (antecedentes familiares de enfermedad coronaria, hipertensin arterial, hipercolesterolemia y diabetes mellitus) mantuvo la OR (2,80

[IC del 95%, 1,35-5,80]). Los que dejaron de fumar presentaron una OR ajustada de 0,90 (IC del 95%, 0,47-1,71)

respecto a los no fumadores, mientras que los que continuaron fumando presentaron una OR ajustada para un

nuevo IAM de 2,90 (IC del 95%, 1,35-6,20) respecto a los

que dejaron de fumar.

Conclusiones. El mantenimiento del tabaquismo despus de un IAM se asocia con un riesgo triple de padecer

otro infarto respecto a los pacientes que dejan de fumar.

El abandono del hbito tabquico equipara el riesgo al de

los no fumadores antes del primer infarto.

Palabras clave: Infarto de miocardio. Prevencin.

Enfermedad coronaria. Tabaco. Estilo de vida.

Correspondence: Prof. M. Serrano Martnez

Departamento de Epidemiologa y Salud Pblica. Facultad de Medicina,

Universidad de Navarra,

Irunlarrea, 1. 31080 Pamplona, Spain

E-mail: mserranm@cfnavarra.es

Received 5 September 2002.

Accepted for publication 12 December 2002.

35

SEE EDITORIAL ON PAGES 436-7

Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56(5):445-51

445

Document downloaded from http://www.revespcardiol.org, day 17/08/2014. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited.

Serrano M, et al. Smoking Cessation and Risk of Myocardial Reinfarction in Coronary Patients: A Nested Case-Control Study

vascular risk factors.10,11

ABBREVIATIONS

OR: odds ratio

CI: confidence interval

AMI: acute myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

A healthy lifestyle is the foundation for primary prevention, hence changes in diet and physical exercise

and the cessation of smoking form the basis in of theerapy patients with established heart disease.1 Most

studies of measures recommended for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease analyze the efficacy

of programs aimed at favoring changes in lifestyle or

at increasing the percentage of patients treated with

drugs shown to be effective at delaying progression of

coronary heart disease.2

Smoking has been related with physiopathologic

mechanisms of cardiovascular disease, such as raised

concentrations of carboxyhemoglobin and increases in

fibrinogen and platelet aggregability, as well as changes in vascular reactivity and a reduction in plasma levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL-C).3-6 These

changes, either alone or in combination, favor the appearance of arterial lesions, which lead to progression

of arteriosclerosis and an increased risk of thrombosis.

Most of the evidence regarding the cardiovascular

benefits of smoking cessation comes from randomized

studies which included patients with prior cardiovascular disease. A meta-analysis has recently been published of cohort studies analyzing the benefit of smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease.

The main finding was a combined odds ratio (OR) of

0.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46-0.62) for death,

regardless of sex, study period, observation period

and geographic zone, although the risk of non-fatal

reinfarction was not studied.7

Only one clinical trial examining the efficacy of

multiple risk factor management has shown significant

results for smoking cessation.8 The duration of hospital stay and intensive counseling during recovery from

the acute episode are important for achieving higher

rates of sustained smoking cessation.9

This study was designed to analyze the effectiveness

of our usual program of secondary prevention counseling in reducing the risk of coronary disease, especially relating to smoking cessation after a first AMI,

which is still considered to be one of the main cardio446

Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56(5):445-51

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This 1:1 case-control study included 274 coronary

patients from a cohort of 985 with a firm diagnosis of

AMI from 1980 to 2000 in the Hospital de Navarra.

Patients were included if they were younger than 76

years of age, they survived more than 6 months after

the acute event, and they had received no invasive therapeutic procedure or aorto-coronary bypass.

Diagnosis of all infarctions was made according to criteria of the MONICA project12 (two or more ECGs

with definite changes; an ECG with suggestive changes and abnormal enzymes; or characteristic symptoms and abnormal enzymes). Cases were considered

those patients with fatal or nonfatal reinfarction

from January 1997 to December 2000 (n=142;

men, 90.5%). Data collection was made at the time

of the second infarction. The medical charts were

reviewed to ensure compliance with all the study criteria. The two patients who refused to participate in the

study and the three with inadequate control data (see

below) were excluded from the analysis, giving a final

total of 137 patients interviewed (96.5% of the initial

sample).

One control patient was paired with each case for

the same age (5 years) and sex. The controls were

from the same cohort of patients; i.e., all had had just

one myocardial infarction (based on the criteria as

mentioned above) and after the same secondary prevention period as their corresponding case (10%)

presented no symptoms of coronary disease progression. Data from controls were obtained when they

were matched with their corresponding case. The data

base was ordered by age and the first control who

matched the reference case was chosen. If a control

refused to participate (9 patients), the next suitable

control in the data base was chosen.

The interviews were carried out by two doctors

(EMZ and IEI) and one nurse (BSA), who all received

prior training in a pilot study. Each case-control pair

was interviewed by the same researcher. The interview

was conducted after explaining the reasons for the

study and obtaining informed consent. The questionnaire contained information concerning the following

aspects: previous diseases (1 question), family history

of cardiovascular disease (1 question), work after the

first infarction (3 questions), family and social integration (3 questions), personal attitudes (2 questions,

about feelings of stress and perfectionism) and drug

36

Document downloaded from http://www.revespcardiol.org, day 17/08/2014. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited.

Serrano M, et al. Smoking Cessation and Risk of Myocardial Reinfarction in Coronary Patients: A Nested Case-Control Study

TABLE 1. Number and percentage of cases

and controls in each category according to smoking

status

Cases

Nonsmoker before and

after first AMI

Quit smoking after first AMI

Continued smoking

after first AMI

Total

Controls

51 (37.2%)

48 (35.0%)

54 (39.4%)

67 (48.8%)

38 (27.7%)

137 (100%)

16 (11.7%)

137 (100%)

AMI: acute myocardial infarction.

therapy after the first myocardial infarction (8 questions). Questions about lifestyle before and after the

first infarction included: smoking (4 questions), physical exercise (10 questions), dietary habits (5 questions)

and sexual activity (2 questions). The patients were asked about compliance with the recommended changes

in self-care and about the type and frequency of visits

to their cardiologist, family doctor, and primary care

nurse (13 questions).

If the patient had died (29 cases and 6 controls), or

when the patient was unable to maintain a telephone

conversation due to deafness or cognitive deterioration

(6 cases and 5 controls), the interview was conducted

with a close family member. In these cases, the matching control patient was also interviewed through a

close family member.

Data were recorded in a Microsoft Access data base,

and data for the possible control patients were

obtained from a Microsoft Excel data base. Statistical

analysis was made using SPSS, version 10.0. The odds

ratios were calculated by conditional logistic regression analysis, with the case/control as the dependent

variable. Binary logistic regression models were adjusted to study mortality, with death as the dependent

variable. Percentage differences were calculated with

EpiInfo, version 6.04b.

RESULTS

Mean age was 69.8 years for cases and 69.7

years for controls. The mean time to reinfarction in the

cases was 7.150.51 years. Only 10 cases had a reinfarction 14 years or more after the first AMI. The study

concentrated on lifestyle, drug therapy, and medical and

nursing care during the period between the first infarction and entry to the study, i.e. the time of the most recent infarction in the cases or the time of pairing in the

controls, to determine the duration of secondary prevention.

For the variable smoker in the initial analysis, the

cases and controls were classified as smokers or nonsmokers after their first infarction. For the second conditional logistic regression model they were classified

as "nonsmokers before and after first infarction", "ceased smoking after first infarction" and "continued

smoking after first infarction". The number of patients

included in each category is shown in Table 1.

Table 2 shows possible confounding variables for

cases and controls, as well as percentages differences.

Stopping workafter the first infarction was

associated with a lower frequency of smoking

TABLE 2. Variables which could confound analysis of smoking cessation after a first infarction

Controls

Nonsmoker (%)

Family history

Married

Primary education

Retired

Feelings of stress

Perfectionism

High blood pressure

Dyslipidemia

Diabetes

Antihypertensive therapy

Cholesterol-lowering drugs

Antidiabetic agents

Walking

Dietary changes

Compliance with recommendations

a

29.6

88.9

85.2

37.0

16.7

70.4

40.7

40.7

24.1

31.5

35.2

22.2

85.2

87.0

77.8

Cases

Quit smoking (%) Continue smoking (%) Nonsmoker (%)

26.9

88.1

76.1

41.8

16.4

70.1

55.2

52.2

25.4

53.7

42.4

20.9

91.0

88.1

83.6

18.8

75.0

87.5

68.8b

50.0b

68.8

31.2

75.0a

12.5

31.3

62.5

12.5

75.0

68.8

43.8b

35.3

80.4

84.3

31.4

25.5

64.7

47.1

47.1

35.3

37.3

25.5

23.5

80.4

56.9

86.3

Quit smoking (%) Continue smoking (%)

35.4

91.7

79.2

52.1

22.9

68.8

45.8

43.7

22.9

37.5

40.4

22.9

87.5

68.8

87.5

31.6

78.4

73.7

65.8a

23.7

57.9

55.3

50.0

13.2a

39.5

39.5

10.5

71.1

42.1

60.5b

P<.05 compared with nonsmokers. bP<.05 compared with nonsmokers and those who quit smoking.

37

Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56(5):445-51

447

Document downloaded from http://www.revespcardiol.org, day 17/08/2014. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited.

Serrano M, et al. Smoking Cessation and Risk of Myocardial Reinfarction in Coronary Patients: A Nested Case-Control Study

TABLE 3. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI of a second

myocardial infarction after a first myocardial

infarction according to smoking status (yes/no)

OR (95% CI)

Crude analysisa

Adjusted for lifestyleb

Further adjusted for drug therapyc

Further adjusted for family

and personal historyd

2.83 (1.47-5.47)

2.96 (1.47-5.95)

3.20 (1.56-6.56)

2.80 (1.35-5.80)

Paired by age, sex, hospital, interviewing doctor and duration of secondary

prevention period. bAdjusted for walking, dietary changes and compliance

with recommendations after a first myocardial infarction. cFurther adjusted for

drug therapy (antihypertensive drugs, cholesterol lowering drugs and antidiabetic agents). dFurther adjusted for family history of coronary heart disease

and for the presence of high blood pressure, dyslipidemia and diabetes.

cessation, as well as with greater difficulty stopping

smoking in the controls, who reported a subjective

feeling of stress, which was not reported by the

cases. Moreover, the proportion of patients who

failed to follow treatment advice adequately was

greater among those who continued smoking after

their first infarction. This is consistent with the

responses to the survey.

Smoking after the first infarction was associated with

a reinfarction, with an OR of 2.83 (95% CI, 1.47-5.47).

Interestingly, after adjusting the statistical model for

variables related with walking and dietary modification

after the first infarction, as well as for self-reported

compliance with medical recommendations for secondary prevention, the OR rose to 2.96 (95% CI, 1.475.95). Likewise, inclusion in the model of drug therapy

regimens (antihypertensive drugs, lipid lowering drugs

and antidiabetic agents) increased the OR of a reinfarction to 3.20 (95% CI, 1.56-6.56). However, after including family history of heart disease and risk factors

(hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes), the final OR

was 2.80 (95% CI, 1.35-5.80) (Table 3).

In comparison with nonsmokers, both before and af-

ter the first infarction, the decision to quit smoking resulted in an OR for reinfarction of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.41.42). After adjusting for other lifestyle factors, compliance with recommendations, drug therapy and risk

factors (family history, hypertension, dyslipidemia and

diabetes) the OR was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.47-1.71) (Table

4). Those patients who continued smoking after the

first infarction had an OR for reinfarction of 3.06

(95% CI, 1.53-6.13) compared with those who quit

smoking. After adjustment for other lifestyle factors,

compliance with the recommendations, drug therapy,

high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes

and family history, the OR fell to 2.90 (95% CI, 1.356.20) (Table 4).

In an attempt to evaluate the risk of a further infarction in relation to the number of cigarettes smoked per

day, the conditional logistic regression model was adjusted, using the number of cigarettes divided by 5 as

an independent variable. After inclusion of the same

variables as mentioned above, those patients who continued smoking after the first infarction had an additional risk of reinfarction of 39.5% for each 5 cigarettes

smoked per day (data not shown).

The OR of death was 3.07 (95% CI, 1.13-8.33) for

those patients who continued smoking compared with

those who quit smoking after their first infarction.

DISCUSSION

This study examined several factors influencing secondary prevention in coronary patients after a first

AMI, including counseling aimed at smoking cessation. An observational study is the only possible design due to ethical difficulties arising with planned intervention studies. No differences were found in the

incidence of reinfarction between patients who quit

smoking and those who had never smoked. Those patients who continued smoking after their first myocardial infarction had a three-fold risk of a second infarc-

TABLE 4. Measures of association (OR and 95% CI) for reinfarction in patients who quit smoking vs nonsmokers

and patients who continued smoking vs those who quit

Crude analysisa

Adjusted for lifestyleb

Further adjusted for drug therapyc

Further adjusted for family and personal historyd

Quit smoking vs

nonsmokers

Continue smoking vs

quit smoking

0.82 (0.47-1.42)

0.86 (0.48-1.53)

0.89 (0.48-1.66)

0.90 (0.47-1.71)

3.06 (1.53-6.13)

3.13 (1.50-5.53)

3.34 (1.57-7.08)

2.90 (1.35-6.20)

Paired by age, sex, hospital, interviewing doctor and duration of secondary prevention period. bAdjusted for walking, dietary changes and compliance with recommendations after a first myocardial infarction. cFurther adjusted for drug therapy (antihypertensive drugs, cholesterol lowering drugs and antidiabetic agents).

d

Further adjusted for family history of coronary heart disease and for the presence of high blood pressure, dyslipidemia and diabetes.

448

Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56(5):445-51

38

Document downloaded from http://www.revespcardiol.org, day 17/08/2014. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited.

Serrano M, et al. Smoking Cessation and Risk of Myocardial Reinfarction in Coronary Patients: A Nested Case-Control Study

tion compared to those who quit smoking.

Previous studies have compared the effect of cardiac

rehabilitation programs and lifestyle changes with

usual standards of care.1,2,13 Although programmed interventions resulted in a better prognosis for these patients, none of the seven clinical trials of secondary

prevention which analyzed the effect of smoking cessation and other preventive measures on the incidence

of reinfarction detected any significant differences in

coronary events, and only one study showed an increased rate of smoking cessation in the experimental group.2

Preventive intervention programs do not always improve health outcome,14 and it is not easy to apply proven preventive measures to daily practice.15,16 Other

randomized trials have promoted interventions to improve social support, quality of life and care, but with

uncertain results.2,17

This study was designed to determine the effectiveness of secondary prevention measures in patients

with coronary heart disease. Treatment and counseling

were provided by family doctors and primary care nurses, with occasional visits by the cardiologist.

Standards of clinical management of coronary patients

are constantly being improved.18 The matched design of

this case-control study, with one of the criteria being

the duration of the secondary prevention period, was

aimed at eliminating a possible cohort effect resulting

from varying access to the increasing evidence supporting protective therapy. Our results, therefore, reflect the permanent updating of preventive measures

as they become incorporated into patient care.

Although we included a variable to attempt to adjust

for variations in patients adhesion to counseling, it had

the logical limitations associated with subjective selfreferral. The reliability of this variable can be seen

from the fact that patients who continued smoking reported a lower percentage of adaptation to the recommended treatment. Of note, too, was the fact that the

control group patients who were unable to quit smoking reported a greater percentage of stress. This association has been seen by others.19 For other lifestyles,

the smokers walked less often and introduced fewer

changes into their diet, although these differences were

not statistically significant. The least healthy lifestyles,

therefore, were generally found in the same patients.

Because patients who die shortly after an acute coronary event do not have the opportunity to implement

measures of secondary prevention or to benefit from

health education activities, we excluded those who

survived less than six months after a first infarction.

The beneficial effect of smoking cessation has been

39

studied extensively in relation to the reduction in mortality after an infarction.20-22 Several cohort studies of

coronary patients, collected in a meta-analysis, found

different benefits regarding mortality after cessation of

smoking. Four of these studies reported no significant

individual differences, though the combined risk

showed a reduction in mortality of 46%.7

Few studies analyze the incidence of fatal or non-fatal infarction in coronary patients in relation with smoking. Hedback et al23 found a statistically significant

reduction in the percentage of patients having a reinfarction among those who ceased smoking, after both

five- and ten-year follow-up. However, no multivariate risk analysis was done. In our study, the dependent

variable was the occurrence of a further infarction, either fatal or non-fatal. This event was clearly related

with smoking, independently of other risk factors;

with the analysis showing protection for those who

ceased smoking and an increased risk for those who

continued. A similar effect was reported by Rea et

al,24 who demonstrated that the longer the cigarette-free

period the greater the protection.

Multivariate OR in our study (smokers vs nonsmokers) revealed a possible protective role of the independent variables related with other habits (exercise

and diet) and with drug therapy, as the OR rose from

2.83 to 3.39. Thus, any change towards a beneficial lifestyle or the incorporation of protective treatment

would reduce the risk in those patients who were unable to quit smoking. Although this protection has been

shown with specific drugs, such as beta blockers

among the group of antihypertensive agents,25 our patients were questioned about the use of any antihypertensive drug in order to facilitate their response over

the telephone. The same applies to statins,26 which are

the drugs most often prescribed for hypercholesterolemia during the period of secondary prevention, although few patients were able to identify their generic

name.

Hermanson et al27 found a significant OR of 1.7 for

fatal infarction in patients who continued smoking.

Using mortality as a dependent variable in our study

showed that patients who continued smoking had a

significantly increased risk of death, with an OR of

3.07 compared to those who quit smoking. However,

our study was not designed to analyze mortality in patients with coronary heart disease.

The most important limitation in our study is probably the credibility of the responses given by the patients over the telephone, especially those related to

smoking. Previous studies have relied on the cotinine

assay for validation,28 but this was not possible in our

Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56(5):445-51

449

Document downloaded from http://www.revespcardiol.org, day 17/08/2014. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited.

Serrano M, et al. Smoking Cessation and Risk of Myocardial Reinfarction in Coronary Patients: A Nested Case-Control Study

study due to its design. Nevertheless, telephone interviews are not incompatible with obtaining exact responses, as the interview is conducted voluntarily with

a stranger. The same can be said for the other responses concerning lifestyle and treatment.

Another factor could be the validity of responses given by close relatives. An attempt to control for this

bias was made by interviewing the same type of relative in the control patient, so that the comparative

analysis should still be valid. To avoid interviewer

bias, both the case and the control were interviewed by

the same person. The characteristics of this study, nested in the same cohort of patients, and the pairing between cases and controls according to age, sex, hospital, interviewer and duration of the secondary

prevention period, strengthens the validity of our results. Patients with a prior bypass or angioplasty were

excluded from the study in order to eliminate bias resulting from therapy which could interfere with the natural course of the disease or with the benefits of secondary prevention recommendations. Patients with

reinfarction within six months of the initial event were

also excluded, as a shorter period of secondary prevention can be considered insufficient.

Previous studies have either examined the effects of

intervention programs or analyzed mortality in cohorts

of patients with coronary heart disease according to

smoking habits.2,7 Our observational study of current

secondary prevention also provides a multivariate

analysis of the association between preventive measures and the incidence of reinfarction in patients with

coronary heart disease.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients who have had a first myocardial infarction

are liable to have another. Those who quit smoking

have a three-fold reduction in risk of a second coronary

event compared to those who continue smoking.

Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease requires

responding to the difficulty encountered by some patients

with smoking cessation. Any effort aimed at this will

reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Counseling about smoking cessation should take place in different areas, although primary care nurses, after adequate training, will probably

be able to achieve high rates of smoking cessation.29

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Enrique de los Arcos, chief of the

Servicio de Cardiologa del Hospital de Navarra, for encour-

450

Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56(5):445-51

aging the development of this study and for chart examination. We should also like to thank Mara Jos Urbina (primary care nurse) for her help.

REFERENCES

1. Bairey Merz CN, Rozanski A, Forrester JS. The secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. Am J Med 1997;102:572-81.

2. McAlister FA, Lawson FME, Teo KK, Armstrong PW.

Randomised trials of secondary prevention programmes in coronary heart disease: systematic review. BMJ 2001;323:957-62.

3. Winniford MD, Jansen DE, Reynolds GA, Apprill P, Black WH,

Hillis LD. Cigarette smoking-induced coronary vasoconstriction

in atherosclerotic coronary artery disease and prevention by calcium antagonists and nitroglycerin. Am J Cardiol 1987;59:203-7.

4. Davis JW, Hartman CR, Lewis HD Jr, Shelton L, Eigenberg DA,

Hassanein KM, et al. Cigarette smokinginduced enhancement of

platelet function: lack of prevention by aspirin in men with coronary artery disease. J Lab Clin Med 1985;105:479-83.

5. Kannel WB, DAgostino RB, Belanger AJ. Fibrinogen, cigarette

smoking, and risk of cardiovascular disease: insights from the

Framingham Study. Am Heart J 1987;113:1006-10.

6. Taylor AE, Johnson DC, Kazemi H. Environmental tobacco smoke and cardiovascular disease. A position paper from the Council

on Cardiopulmonary and Critical Care, American Heart

Association. Circulation 1992;86:699-702.

7. Wilson K, Gibson N, Willan A, Cook D. Effect of smoking cessation on mortality after myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of

cohort studies. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:939-44.

8. DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Superko HR, Dennis CA, Thomas RJ,

Lew HT, et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern

Med 1994;120:721-9.

9. Di Tullio M, Granata D, Taioli E, Broccolino M, Recalcati F,

Zaini G, et al. Early predictors of smoking cessation after myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol 1991;14:809-12.

10. Rodrguez Artalejo F, Banegas Banegas JR. Era necesario demostrar tambin en Espaa que la colesterolemia y el tabaco son factores de riesgo cardiovascular? Rev Esp Cardiol 2001;54:1141-2.

11. Ordovs JM. Colesterol y tabaco: clsicos que perduran en el

tiempo. Rev Esp Cardiol 2001;54:1143-5.

12. WHO MONICA Project. MONICA manual. Geneva: WHO, 1990;

part IV(a): p. 11-32.

13. Ades PA. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2001;12:892-902.

14. Jolly K, Bradley F, Sharp S, Smith H, Thompson S, Kinmonth

AL, et al, for the SHIP Collaborative Group. Randomised controlled trial of follow up care in general practice of patients with

myocardial infarction and angina: final results of the

Southampton heart integrated care project (SHIP). BMJ

1999;318:706-11.

15. Brady AJ, Oliver MA, Pittard JB. Secondary prevention in

24,431 patients with coronary heart disease: survey in primary

care. BMJ 2001;1322:463.

16. Van Berkel TF, Boersma H, De Baquer D, Deckers JW, Wood D.

Registration and management of smoking behaviour in patients

with coronary heart disease. The EUROASPIRE survey. Eur Heart

J 1999;20:1630-7.

17. Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly

M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A

randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:999-1006.

18. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice.

Recommendation of the Second Joint Task Force of European

and other Societies on Coronary Prevention. Eur Heart J

1998;19:1434-503.

19. Greenwood DC, Muir KR, Packham CJ, Madeley RJ. Stress, so40

Document downloaded from http://www.revespcardiol.org, day 17/08/2014. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited.

Serrano M, et al. Smoking Cessation and Risk of Myocardial Reinfarction in Coronary Patients: a Nested Case-Control Study

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

41

cial support, and stopping smoking after myocardial infarction in

England. J Epidemiol Community Health 1995;49:583-7.

Johansson S, Bergstrand R, Pennert K, Ulvenstam G, Vedin A,

Wedel H, et al. Cessation of smoking after myocardial infarction

in women. Effects on mortality and reinfarctions. Am J

Epidemiol 1985;121:823-31.

Aberg A, Bergstrand R, Johansson S, Ulvenstam G, Vedin A,

Wedel H, et al. Cessation of smoking after myocardial infarction.

Effects on mortality after 10 years. Br Heart J 1983;49:416-22.

Mulcahy R, Hickey N, Graham IM, MacAirt J. Factors affecting

the 5 year survival rate of men following acute coronary heart disease. Am Heart J 1977;93:556-9.

Hedback B, Perk J, Wodlin P. Long-term reduction of cardiac

mortality after myocardial infarction: 10-year results of a comprehensive rehabilitation programme. Eur Heart J 1993;14:831-5.

Rea TD, Heckbert SR, Kaplan RC, Smith NL, Lemaitre RN,

Psaty BM. Smoking status and risk for recurrent coronary

events after myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2002;

137:494-500.

25. Spinler SA, Hilleman DE, Cheng JW, Howard PA, Mauro VF,

Lopez LM, et al. New recommendations from the 1999 American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association acute myocardial infarction guidelines. Ann Pharmacother 2001;35:589617.

26. Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised

trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart

disease: The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S).

Lancet 1994;344:1383-9.

27. Hermanson B, Omenn GS, Kronmal RA, Gersh BJ. Beneficial

six-year outcome of smoking cessation in older men and women

with coronary artery disease. Results from the CASS registry. N

Engl J Med 1988;319:1365-9.

28. Rigotti NA, McKool KM, Shiffman S. Predictors of smoking cessation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Results of a randomized trial with 5-year follow-up. Ann Intern Med 1994;

120:287-93.

29. Canga N, De Irala J, Vara E, Duaso MJ, Ferrer A, MartnezGonzlez MA. Intervention study for smoking cessation in diabetic patients: a randomized controlled trial in both clinical and primary care settings. Diabetes Care 2000;23:1455-60.

Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56(5):445-51

451

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- MR GMAT Combinatorics+Probability 6EDokument176 SeitenMR GMAT Combinatorics+Probability 6EKsifounon KsifounouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Graduate Tracer StudyDokument4 SeitenGraduate Tracer StudyRodhel Mark Julian Palermo100% (5)

- Eclipse Phase Ghost in The ShellDokument27 SeitenEclipse Phase Ghost in The ShellMeni GeorgopoulouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review of SystemsDokument3 SeitenReview of SystemsAnonymous 8rsxG4100% (1)

- Tthe Sacrament of Reconciliation1Dokument47 SeitenTthe Sacrament of Reconciliation1Rev. Fr. Jessie Somosierra, Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fernández Kelly - Death in Mexican Folk CultureDokument21 SeitenFernández Kelly - Death in Mexican Folk CultureantoniadelateNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Hospitals in Leyte and SamarDokument5 SeitenList of Hospitals in Leyte and SamarAnonymous 8rsxG450% (2)

- (AC-S08) Week 08 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Weekly Quiz - INGLES III (14653)Dokument3 Seiten(AC-S08) Week 08 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Weekly Quiz - INGLES III (14653)Eduardo Arucutipa60% (5)

- Philippine Provinces. Regular, ContractualDokument5 SeitenPhilippine Provinces. Regular, ContractualAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Audit Checklis Part1-Section 10Dokument7 SeitenAudit Checklis Part1-Section 10Anonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Proposal To Add 1 Unit For NCM 103 LectureDokument1 SeiteProposal To Add 1 Unit For NCM 103 LectureAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Midterm Schedule First Sem 2016-2017Dokument2 SeitenMidterm Schedule First Sem 2016-2017Anonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- ProductionDokument5 SeitenProductionAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Health History Physical Assessment 2012Dokument28 SeitenHealth History Physical Assessment 2012loglesb1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Exer 1 - CrabDokument6 SeitenExer 1 - CrabAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Proyekto Sa Filipino: Lib-Og Elementary School SampaguitaDokument1 SeiteProyekto Sa Filipino: Lib-Og Elementary School SampaguitaAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Review of Systems Checklist for General Health AssessmentDokument1 SeiteReview of Systems Checklist for General Health Assessmentammen17Noch keine Bewertungen

- Eiffel TowerDokument2 SeitenEiffel TowerAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- French 1-100 Lec GuideDokument2 SeitenFrench 1-100 Lec GuideAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

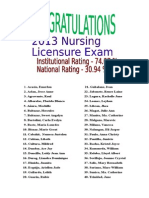

- List of 2013 PassersDokument1 SeiteList of 2013 PassersAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Name in Signat Ure Out Signat Ure Name in Signature Out Signatu ReDokument1 SeiteName in Signat Ure Out Signat Ure Name in Signature Out Signatu ReAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Questionnaire GTS Edited During WorkshopDokument3 SeitenQuestionnaire GTS Edited During WorkshopAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- BIR FormDokument4 SeitenBIR FormfyeahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation Title: Your Company InformationDokument3 SeitenPresentation Title: Your Company InformationAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Click To Edit Master Title StyleDokument4 SeitenClick To Edit Master Title StyleAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- VSU CN Faculty learn IM development (39Dokument1 SeiteVSU CN Faculty learn IM development (39Anonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Repro DrugsDokument6 SeitenRepro DrugsAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ana N Physio Cardio-GutDokument56 SeitenAna N Physio Cardio-GutAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Click To Edit Master Title StyleDokument4 SeitenClick To Edit Master Title StyleAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation Title: Your Company InformationDokument3 SeitenPresentation Title: Your Company InformationAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- 388Dokument4 Seiten388Anonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation TitleDokument4 SeitenPresentation TitleAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fear ArousalDokument20 SeitenFear ArousalAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Nursing On An Acute Stroke UnitDokument10 SeitenUnderstanding Nursing On An Acute Stroke UnitAir-chan BuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barriers IpcDokument3 SeitenBarriers IpcAnonymous 8rsxG4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Solutions Manual For Corporate Finance, 6e Jonathan BerkDokument7 SeitenSolutions Manual For Corporate Finance, 6e Jonathan Berksobiakhan52292Noch keine Bewertungen

- Repeaters XE PDFDokument12 SeitenRepeaters XE PDFenzzo molinariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ariston Oven ManualDokument16 SeitenAriston Oven ManualJoanne JoanneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 20: Where Is Sapa: 2.look, Read and CompleteDokument4 SeitenUnit 20: Where Is Sapa: 2.look, Read and CompleteNguyenThuyDungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urbanization As A Transformative Force: Quick FactsDokument20 SeitenUrbanization As A Transformative Force: Quick FactsJulio CovarrubiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Giai Thich Ngu Phap Tieng Anh - Mai Lan Huong (Ban Dep)Dokument9 SeitenGiai Thich Ngu Phap Tieng Anh - Mai Lan Huong (Ban Dep)Teddylove11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Quantitative Techniques For Business DecisionsDokument8 SeitenQuantitative Techniques For Business DecisionsArumairaja0% (1)

- David Emmett & Graeme Nice - What You Need To Know About Cannabis - Understanding The FactsDokument120 SeitenDavid Emmett & Graeme Nice - What You Need To Know About Cannabis - Understanding The FactsJovana StojkovićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christian Ministry Books: 00-OrientationGuideDokument36 SeitenChristian Ministry Books: 00-OrientationGuideNessieNoch keine Bewertungen

- CARAGA REGIONAL SCIENCE HIGH SCHOOL ASSESSMENT #1Dokument3 SeitenCARAGA REGIONAL SCIENCE HIGH SCHOOL ASSESSMENT #1Joana Jean SuymanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rational design of Nile bargesDokument8 SeitenRational design of Nile bargesjhairNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeff Roth CVDokument3 SeitenJeff Roth CVJoseph MooreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yale Film Analysis WebsiteDokument5 SeitenYale Film Analysis WebsiteizmcnortonNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECUMINISMDokument2 SeitenECUMINISMarniel somilNoch keine Bewertungen

- FA Program BrochureDokument25 SeitenFA Program BrochureThandolwenkosi NyoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Volleyball ReflectionDokument1 SeiteVolleyball ReflectionJake Santos100% (1)

- AMSY-6 OpManDokument149 SeitenAMSY-6 OpManFernando Piñal MoctezumaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shah Wali Ullah Syed Haji Shariat Ullah Ahmad Barelvi (Notes)Dokument2 SeitenShah Wali Ullah Syed Haji Shariat Ullah Ahmad Barelvi (Notes)Samreen KapasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brother LS2300 Sewing Machine Instruction ManualDokument96 SeitenBrother LS2300 Sewing Machine Instruction ManualiliiexpugnansNoch keine Bewertungen

- IDokument8 SeitenICarlaSampaioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3DO For IPDokument7 Seiten3DO For IPHannah Angela NiñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment No1 of System Analysis and Design: Submitted To Submitted byDokument7 SeitenAssignment No1 of System Analysis and Design: Submitted To Submitted byAnkur SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oil Immersed TransformerDokument8 SeitenOil Immersed TransformerAbdul JabbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tentative Quotation For Corporate Video (5 Minutes)Dokument2 SeitenTentative Quotation For Corporate Video (5 Minutes)Lekha JauhariNoch keine Bewertungen

- FedSupport Codebook FY2020Dokument259 SeitenFedSupport Codebook FY2020Aaron BlackmonNoch keine Bewertungen