Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Results of A Primary Care Program

Hochgeladen von

RajDarvelGillOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Results of A Primary Care Program

Hochgeladen von

RajDarvelGillCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Refugees and Medical Student Training: Results of a Program in Primary Care

Frances G. Saad, MSW School of Social Work

Family Medicine Research Institute

State University of New York at Buffalo

Leader- Kim Griswold, MD, MPH

Family Medicine Research Institute

State University of New York at Buffalo

Joan B. Kernan, BS

Family Medicine Research Institute

State University of New York at Buffalo

Timothy J. Servoss, MA

Family Medicine Research Institute

State University of New York at Buffalo

Christine M. Wagner, MSW

Family Medicine Research Institute

State University of New York at Buffalo

Luis E. Zayas, Ph.D.

Family Medicine Research Institute

State University of New York at Buffalo

Sally Speed, Director

NYS Medicaid Training Institute

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Abstract

Background: Medical schools have been responding to the increased diversity of the United

States population by incorporating cultural competency training in their curriculum. This paper

presents results from a pre and post survey of medical students who participated in a training

program which included evening clinical sessions for refugee patients and related educational

workshops.

Methods: A self-assessment survey was administered at the beginning and at the end of the

academic year, to measure cultural awareness of participating medical students.

Results: Over the three years of the program, over 133 students participated and 95 (73%)

completed pre and post surveys. Participants rated themselves significantly higher in all three

domains of the cultural awareness survey after completion of the program.

Conclusions: The opportunity for medical students to work with refugees in the provision of

health care presents many opportunities for the students, including communications lessons,

learning about other cultures, and practicing basic health care skills. An important issue to

consider is the power differential between those in medicine and patients who are refugees.

To

avoid reinforcing stereotypes, medical programs and medical school curricula can incorporate

efforts to promote reflection on provider attitudes, beliefs and biases.

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Overview Box:

What is already known on this subject:

Medical schools are offering training in cultural awareness.

When exposed to cultural diversity training, students gain in knowledge.

What this study adds:

Students reported increased knowledge of psychosocial and cultural issues that had an impact on refugee health.

Experiential learning opportunities through student

encounters with refugees expanded students own cultural awareness.

Suggestions for further research:

Tracking of students who participate in similar

programs to study whether there are long-term changes in attitude and knowledge.

Conduct future studies with comparison groups to

determine program effectiveness, and longer-term outcomes.

Investigate the role of power in doctor-patient

relationships that involve vulnerable populations.

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Background

Physicians are increasingly attuned to the cultural differences in the populations they

serve. Medical schools have responded to this increasing diversity by incorporating different

methods of cultural awareness training into their curricula. The Liaison Committee on Medical

Education (LCME), which sets accreditation standards for medical schools, requires that faculty

and students must demonstrate an understanding of the manner in which people of diverse

cultures and belief systems perceive health and illness and respond to various symptoms,

diseases, and treatments. [1]

Whether didactic teaching and curriculum enhancements make an impact on medical

students awareness of cultural nuance, particularly in the early stages of medical training, may

be difficult to discern. Developing insight and cultural awareness has been described as a

journey, not something that happens overnight; and thus early medical training exposure to

cultural diversity among patients and families can lay a framework for later learning.[2,3]

Curricula from various medical schools focus on different approaches to cultural

awareness training. In one school, the first-year medical student clinical course used problembased learning which included the influence of cultural and psychosocial factors on health beliefs

and practices, and a video on proper use of interpreters. Before and after the course, students

completed a Health Beliefs Attitudes Survey (HBAS) to assess attitudinal change. These

students self ratings of the importance of measuring patient opinions and determining health

beliefs were significantly improved following completion of the curriculum.[3] In another study,

medical students participated in a "Global Multicultural Track" elective in Family Medicine and

Community Health. After taking the curriculum, the participants demonstrated a higher level of

cultural competence, more tolerance of people with different cultural backgrounds and more

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

acceptance of persons who did not speak English.[4] At another university, a more in-depth

year-long course, Culture and Diversity, was designed around core competencies outlined by

the American Medical Student Associations Promoting, Reinforcing and Improving Medical

Education project (AMSA PRIME). [5] This course included lectures, videos, simulation,

demonstrations, role-plays and workshops. Students completed a self-report questionnaire

during the first and last sessions of the course. Results of that program evaluation showed that

students had significantly improved their knowledge, skills and attitudes related to cultural

competency. However, in a Canadian study, medical students who participated in a new course

addressing social and cultural issues reported no differences in cultural awareness when

compared with students who had not taken the new course. [6]

At our medical school, students responded to health needs of newly arrived refugees in

our community. With a family medicine faculty preceptor, the students organized regular

volunteer clinical sessions to care for refugee families.[7] Based on this work, the Refugee

Health and Cultural Awareness Training Program was developed to provide: 1) patient-based

encounters through which medical students could experience cultural differences; 2) techniques

for the appropriate use of interpreters and communication skills; and, 3) didactic teaching with a

focus on ethnic and cultural issues in health care. The specific goals of the program were to

increase: 1.) self-awareness regarding ones own ethnicity and culture, 2.) understanding and

appreciation for cultural diversity in the health care setting, 3.) communication skills including

ability to utilize interpretive services, and 4.) skills for establishing collaborative partnerships

between providers and patients. This elective program is offered to 1st-4th year medical students.

This paper reports findings from three years of student involvement, for participants from

all four years of medical school.

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Our evaluation question was: 1) Does an experiential learning format improve medical students

perceptions of their cultural awareness? This study was approved by our institutional IRB.

Methods

Medical Students

A total of 133 medical students participated in this voluntary elective over three academic

years, 2002-2005. This convenient sample of first through fourth year medical students involved

a pre and post program self-assessment evaluation. The student breakdown was: 75% first year,

16% second year and 9% third or fourth year. The majority of students were female (73%) and

ages ranged from 22 to 32, with an average age of 25. Of the students reporting their ethnic

background, 58% were white, 10% African or African-American, 16% were East Asian or

Pacific Islander, 14% were Indian or from a Middle Eastern Nation and 2% were Latino.

Participants were recruited in the first week of medical school orientation during luncheons and

club fairs, and later through word of mouth by the medical students. Refugee individuals and

families

Refugees are resettled across the United States through the Office of Refugee

Resettlement (ORR). Cash and medical assistance benefits are available to needy refugees who

are not eligible for other cash or medical assistance programs through the ORR, for up to eight

months after arrival in the U.S. [8] In our urban metropolitan area, we worked with two specific

inner-city agencies. Refugees are assisted by the agency with housing, job searches, English as a

Second Language (ESL) classes, and access to primary health care. The two agencies had

enduring collaborative relationships with each of the medical clinics utilized in our training

program.

Clinical Experience

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Medical students attended two evening clinics where newly arrived refugees were seen

by the family physicians at the two designated clinical sites. Each of the physician preceptors

had experience in international medical settings, and provided the full scope of primary care,

including prenatal and delivery care, to a diverse, multi-lingual population in inner-city

University-based clinics.

An initial requirement of the program was attendance at an introductory lecture where

students completed a pre-assessment cultural competency survey and were provided information

on refugee status and health. Students were required to participate in at least two refugee clinic

sessions during the academic year.

Prior to the clinical encounter, a cultural lesson was given by a case manager employed

by a refugee resettlement agency. The cultural lesson consisted of a 30-45 minute review of the

background and history of the particular refugee group the student would encounter that session.

Students received instruction on interpretation methods (telephonic and/or in-person), and the

importance of matching gender for interpretation was emphasized. Then students met with the

physician preceptors for approximately hour, while refugee patients were being screened by

office staff. Physicians discussed with students how to approach the interview, and make

sensitive inquiry about the individuals life story and journey to the United States. Physicians

introduced students to the refugee individual or family, and students then obtained a history from

the patient. Patients were asked if they had any health concerns or medical problems that needed

to be addressed. The remainder of the clinical encounter consisted of the physical exam,

provided by the preceptor with assistance of the medical student. Together, the preceptor,

student and patient discussed the assessment and medical plan. Preventive and follow-up care

was explained to patients. All refugee patients established a primary care home at the medical

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

office they attended for this first visit.

Immediately following the clinical session, students were debriefed by the case manager

and a social worker, on their experience, either individually or with another medical student.

Students were asked about their experience with the refugee patients, in terms of communication,

cultural, clinical or psychosocial issues, and emotional content of the interview. Students were

then asked to offer suggestions and/or improvements for the program. At the end of the

academic year students were required to attend an end of training program luncheon where they

complete the post assessment questionnaire.

Other Activities

As a result of feedback from our students, we incorporated more activities for the medical

students to meet with refugees. Story-telling sessions were held at lunch time at the medical

school so that more students could attend and where refugees told their life stories. We

incorporated monthly brown-bag lunches whereby different lectures were given on refugee

issues including legal aspects of immigration, and health care issues of refugees such as mental

health, female circumcision, lead poisoning, and tuberculosis. Program activities offered during

the academic year are listed in Table 1.

Analysis of the Self-Assessment Questionnaire

The Cultural Awareness Self-Assessment Questionnaire is a self-report 5-point (1 =

Excellent, 2 = Good, 3 = Fair, 4 = Poor, 5 = None) Likert scale survey adapted by the authors

from a questionnaire developed at Portland State University. [9] An exploratory principal

components analysis with varimax rotation was used to examine the measurement structure of

the instrument. As a result of this analysis, three of the original 17 items were dropped, leaving

14 items loading on three principal components which accounted for approximately 67% of the

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

variance among the items. The three domains measured by the instrument correspond to

knowledge of psychosocial issues affecting refugees (seven items, Cronbachs alpha = .88; 95%

CI = .85--.91), knowledge of cultural issues (four items, Cronbachs alpha = .87, 95% CI = .

83--.90), and communication skills (three items, Cronbachs alpha = .78, 95% CI = .70--.84).

Component loadings, communalities and more specifics from the principal components analysis

are located in Table 2.

Data Analysis

Scores for the three components of the self-assessment survey (psycho-social issues,

cultural issues, and communication) were computed as the average of the items corresponding to

each component. In the case of item non-response, a person-specific estimate was calculated for

missing items within a given component provided at least 50% of the items within that scale

were non-missing. The average score within that scale across the completed items was used as

this estimate. For example, if someone only answered six of the seven items within the psychosocial issues scale, the average across the six completed items would be substituted for the

missing seventh item. This general approach to item non-response has been supported by other

research.[10] Comparisons of pre- and post-test scores on the three components were made

using paired-samples t-tests. Effect sizes were calculated as pre-test means minus post-test

means divided by pre-test standard deviations. Multiple regression was used to examine the

influence of several covariates on post-test scores while controlling for pre-test levels of cultural

awareness. Covariates to be examined included student characteristics such as age, sex,

nationality, number of languages spoken, and number of foreign countries visited.

Results

Completers vs. non-completers

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Of the 133 students who participated in the program, 131 provided usable pre-test

information. Of these 131 students, 95 (73%) completed post-tests; 36 (27%) did not complete

post-tests. Post-test non-completers were more likely to be male, X2(1) = 9.04, p = .003, but did

not differ significantly from post-test completers in terms of age, ethnic background, nationality,

number of clinics attended and most importantly, pre-test levels on any of the three cultural

awareness instrument scales.

Pre- Post comparisons

Students reported significant improvement in all three domains of the cultural awareness

self-assessment instrument. For psycho-social issues, students had a pre-test mean of 3.15 and

improved to a post-test mean of 2.15 (lower values indicate a more positive assessment), t(94) =

14.84, p < .001, effect size = 1.44. For cultural issues, students had a pre-test mean of 2.55 and

improved to a post-test mean of 1.98, t(94) = 9.05, p < .001, effect size = 0.82. Finally, for

communication, students improved from a pre-test mean of 3.36, to a post-test mean of 2.02,

t(94) = 14.43, p < .001, effect size = 1.57.

What demographic factors affected improvement in cultural awareness?

A series of regression analyses were conducted to determine if differences in post-test

levels in the three domains of cultural awareness could be accounted for by student age, sex,

nationality, experience visiting other countries, or number of languages spoken, while controlling

for pre-test levels of cultural awareness in each domain.

For the psycho-social issues domain, none of these student characteristics significantly

predicted post-test levels when controlling for pre-test scores. However, in both the cultural

issues and communication domains, gender emerged as an important predictor. Specifically,

when controlling for pre-test levels, females had post-test scores in the cultural issues domain

10

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

that were .368 points (.272 standard deviation units) higher than their male counterparts, p = .

002. In the communication domain, similar findings emerged. Controlling for pre-test levels,

females had post-test scores in the communication domain that were .270 points (.204 standard

deviation units) higher than their male counterparts, p = .048.

Discussion

This Refugee Health and Cultural Awareness Training Program presented an opportunity

for medical students at our university to learn about diverse cultures by providing an immediate

experience of interacting with patients from other cultures. The goal of our study was to offer

exposure to providing culturally competent care in a primary care setting. Results from the pre

and post survey questions indicated that after an academic year of participating in the program,

students reported increased knowledge of psycho-social and cultural issues that had an effect on

refugee health. Students also reported improved communication skills. Some improvements

appeared to be slightly more pronounced for female participants, particularly in the knowledge of

cultural issues and communication skills domains; this finding may reflect bias of this

convenience sample.

Though we adapted our tool from a validated questionnaire, the survey

we used has not been further validated. The instrument did show a trend in terms of measurement

structure and internal consistency among the 14 questions.

The use of a self-report survey and self-selection in volunteering for this program

presents limitations in analysis of these outcomes. Because of the elective nature of the program,

it is possible that students who volunteered to participate may be predisposed to learning about

other cultures, and therefore may have contributed to a biased sample. Thus, differences in

student responses pre and post program may have been due to characteristics of this particular

sample. Additionally, this program did not have the scope or resources available to track longer-

11

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

term outcomes of participating students. It would be important in subsequent work to assess if

lessons learned by students translate into their future medical careers.

An important issue to consider is the power differential between those in medicine

(professional, many White and privileged) and patients who are refugees. Refugees possess

unique experiences and backgrounds that may make them more vulnerable to inequalities and

potential abuses of power within the health care system. [11] Addressing the power differential

between doctors and patients is an integral part of cultural awareness and competency, requiring

an in-depth self-assessment on the part of care providers. To avoid reinforcing stereotypes,

medical programs and medical school curricula can incorporate efforts to promote reflection on

provider attitudes, beliefs and biases; both to develop skills for critical self-awareness and to

develop understanding of power and privilege. [12]

The findings of this study support recent literature that medical students

gain in knowledge and skills when exposed to cultural diversity training. [3,4,13] Some of the

techniques used in this program complement recent recommendations for teaching the

psychosocial aspects of care in the clinical setting. [14] Those recommendations emphasize

connecting personally with the trainee, role modeling, creating an enjoyable learning

environment, and provision of feedback to the trainee. Our training program relied on role

modeling by preceptors, and laid particular emphasis on the possibility of traumatic stress

experienced by refugees. The program format offered an introduction in the journey towards

cultural competence by incorporating actual experiential learning in the clinic; a method

effective in medical student training.[15] The paradigm of meaningful encounters with refugee

patients may be useful to impart a pattern recognition for the student that crosses all cultures. If

he/she can learn to communicate and respect patients from different cultures and backgrounds,

12

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

then he/she will use such skills in all their encounters with patients, regardless of background.

This training program may offer a potential model for other medical schools to link with refugee

communities to offer medical students opportunities to expand their communications skills, and

provide health care for those newly arrived in our country.

13

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Angela Henke for her invaluable assistance on this manuscript.

We thank all the medical students who participated in the program, and particularly the refugee

adults and children for teaching us.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the New York State Department of Health for providing

training program funding, and the University at Buffalos Department of Family Medicine for its

institutional support. We also wish to recognize the International Institute of Buffalo, Journeys

End Refugee Services, Jericho Road Family Practice, and Niagara Family Health Center of

Buffalo for their superb collaboration.

New York State Department of Health. Funding for this research project was provided by the

Department of Health Training Resource System, Contract year 2004: Project 1037112, Award:

31177; Contract year 2005: Project 1044887, Award 34963, through the Center for Development

of Human Services, College Relations Group, Research Foundation of SUNY, Buffalo State

College.

14

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

References

1.

Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School:

Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the M.D. Degree.

Washington, DC. October, 2004.

2.

Like RC. Culturally competent managed health care: a family physician's perspective. J

Transcult Nurs 1999. 10(4): p. 288-9.

3.

Crosson J, Deng W, Brazeau C, Boyd L, Soto-Greene M. Evaluating the effect of cultural

competency training on medical student attitudes. Fam Med 2004. 36(3): p. 199-203.

4.

Godkin M., Savageau J. The effect of a global multiculturalism track on cultural

competence of preclinical medical students. Fam Med 2001. 33(3): p. 178-86.

5.

Crandall S, George G, Marion G, Davis S. Applying theory to the design of cultural

competency training for medical students: a case study. Acad Med 2003. 78(6): p. 58894.

6.

Beagan BL. Teaching social and cultural awareness to medical students: "it's all very

nice to talk about it in theory, but ultimately it makes no difference". Acad Med 2003.

78(6): p. 605-14.

7.

Griswold KS. Refugee health and medical student training. Fam Med 2003. 35(9): p.

649-54.

8.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and

Families, Office of Refugee Resettlement. Retrieved August 1, 2005 from Office of

Refugee Resettlement website: http://www.acf.dhhs.gov/programs/orr/mission/index.htm

15

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

9.

Mason JL. Cultural competence self-assessment questionnaire: a manual for users.

Portland, OR: Portland State University, Research and Training Center on Family

Support and Childrens Mental Health. 1995.

10.

Ware JE, Davies-Avery A, & Brook RH. (1980). Conceptualization and measurement of

health for adults in the Health Insurance Study. Volume VI: Analysis of relationships

among health status measures. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation (publication

no. R-1987/6-HEW).

11.

Candib LM, Gelberg L. How will family physicians care for the patient in the context of

family and community? Fam Med. Apr 2001;33(4):298-310.

12.

Robins LS, Fantone JC, Hermann J, Alexander GL, Zweifler AJ. Improving cultural

awareness and sensitivity training in medical school. Acad Med. Oct 1998;73(10

Suppl):S31-34.

13.

Tang TS, Fantone JC, Bozynski MEA., Adams BS. Implementation and evaluation of an

undergraduate Sociocultural Medicine Program. Acad Med 2002. 77(6): p. 578-85.

14.

Kern DE, Branch WT, Jackson JL, Brady DW, Feldman MD, Levinson W, Lipkin M.

Teaching the psychosocial aspects of care in the clinical setting: practical

recommendations. Acad Med 2005. 80(1): p. 8-20.

15.

Smits PB, JH Verbeek, and CD de Buisonje. Problem based learning in continuing

medical education: a review of controlled evaluation studies. Bmj 2002. 324(7330): p.

153-6.

16

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Table 1: Additional Components of Refugee Health and Cultural Awareness

Training Program

Activity

Storytelling

Description

1-hour evening session where

refugees tell their life stories.

i.e. Iraqi, Liberian, Sudan.

Mini-Clinical

2-hour clinical sessions entailing

immunizations

initials screenings-lab/PPD,

blood pressure screening.

Health Education Sessions

1 hour educational sessions presented

by medical students that include

health topics related to refugees i.e.

nutrition, hygiene, smoking.

Brown Bag

1-hour educational sessions presented

on various refugee topics i.e. legal

issues, mental health, female health

care, birth control, Diabetes, Heart

Disease

17

Medical Students and Cultural Awareness

Table 2: Component Loadings, Communalities (h2), and Percents of Variance for Principal

Components Extraction and Varimax Rotation on 14 Cultural Awareness Items.

Items

-Rate your familiarity with the types of trauma that

refugee groups may exhibit coming into the U.S.

-Rate your knowledge of basic mental health care

issues presented by refugee groups

-Rate your awareness of basic non-medical needs of

refugee for a successful integration into their new

host society

-Rate your awareness of the factors that force

people from other countries to seek refuge in U.S.

-Rate your familiarity with the challenges that

refugee groups pose in the primary care setting

-Rate your awareness of the legal rights of refugees

and other immigrant groups when interfacing with

the U.S. health care system

-How knowledgeable are you regarding refugee

issues overall

-Rate your knowledge of the relationship between

culture and gender issues

-Rate your knowledge of the partnership between

culture and power issues

-Rate your knowledge of the influence of religion in

health care behaviors

-Rate your knowledge of the relationship between

culture and social class/status

-Rate your familiarity with translation and

interpretation services in the health care setting

-Rate your understanding of the difference between

translation and interpretation

-Rate your knowledge of strategies for effective

health education among refugee patients

SSL

Percent of Variance

PsychoSocial

Issues

Cultural

Issues

Communi

-cation

h2

.801

.258

.014

.71

.792

.204

.275

.74

.762

.103

.184

.63

.697

.364

.108

.63

.666

.321

.383

.69

.591

.242

.289

.49

.502

.386

.130

.42

.285

.854

.029

.81

.315

.845

.059

.82

.118

.753

.237

.64

.381

.748

.087

.71

.215

-.020

.862

.79

.137

.069

.789

.65

.222

.320

.727

.68

3.834

27.39

3.239

23.14

2.331

16.65

18

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Investigations (Gout) : 1 Tests To OrderDokument2 SeitenInvestigations (Gout) : 1 Tests To OrderRajDarvelGillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pigmentation Disorders: Medicine, Elsevier, China, Pp. 1295-1296Dokument1 SeitePigmentation Disorders: Medicine, Elsevier, China, Pp. 1295-1296RajDarvelGillNoch keine Bewertungen

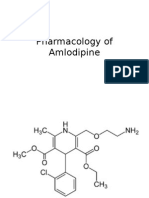

- Pharmacology of AmlodipineDokument6 SeitenPharmacology of AmlodipineRajDarvelGillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anatomy of Pituitary GlandDokument8 SeitenAnatomy of Pituitary GlandRajDarvelGillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Panel Discussion Maternal and Child Health Improved in Urban SettingDokument4 SeitenPanel Discussion Maternal and Child Health Improved in Urban SettingRajDarvelGillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treatment & Management: Antithyroid DrugsDokument3 SeitenTreatment & Management: Antithyroid DrugsRajDarvelGillNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- An Examination of The Effect of Product Performance On Brand Reputation, Satisfaction and LoyaltyDokument17 SeitenAn Examination of The Effect of Product Performance On Brand Reputation, Satisfaction and Loyaltyjoannakam0% (1)

- 5 D Earthsoft Personality Development Practical File 4Dokument111 Seiten5 D Earthsoft Personality Development Practical File 4Rajendra Rakhecha100% (1)

- Attitudes of Audience Towards Repeat Advertisements A Case of Pepsi AdsDokument4 SeitenAttitudes of Audience Towards Repeat Advertisements A Case of Pepsi AdsDev RishabhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive DissonanceDokument11 SeitenCognitive DissonanceAnand PrasadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integrated Advertising Promotion and Marketing Communications 7th Edition Clow Solutions Manual DownloadDokument30 SeitenIntegrated Advertising Promotion and Marketing Communications 7th Edition Clow Solutions Manual DownloadArnita Walden100% (25)

- Review 3 - KeyDokument4 SeitenReview 3 - KeyPhạm MơNoch keine Bewertungen

- DownloadDokument22 SeitenDownloadMIKAELA THERESE OBACHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Work Values and Teaching Performance of Physical Education Teachers in Secondary Schools of Central Area Districts, Division of Northern SamarDokument14 SeitenWork Values and Teaching Performance of Physical Education Teachers in Secondary Schools of Central Area Districts, Division of Northern SamarJournal of Interdisciplinary PerspectivesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Career PlateauDokument7 SeitenCareer PlateauSyaidatina Aishah0% (1)

- Attitude and MindsetDokument22 SeitenAttitude and MindsetAbdur RofiqNoch keine Bewertungen

- PornDokument38 SeitenPorncarrier lopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Individual Differences and BehaviorDokument40 SeitenManaging Individual Differences and BehaviorDyg Norjuliani100% (1)

- The Learning Process: NCM 102-HEALTH EDUCATION AY:2020-2021Dokument74 SeitenThe Learning Process: NCM 102-HEALTH EDUCATION AY:2020-2021CLARENCE REMUDARONoch keine Bewertungen

- Tugas SP Bahasa Inggris Natasya (1511080268)Dokument30 SeitenTugas SP Bahasa Inggris Natasya (1511080268)natasya979Noch keine Bewertungen

- Conflict & NegotiationDokument28 SeitenConflict & Negotiationaadis191Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Research Proposal Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of The Requirements For The Degree of Marketing ManagementDokument40 SeitenA Research Proposal Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of The Requirements For The Degree of Marketing ManagementJossi AbuleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 9 - Identity Contact and Intergroup Encounters. FinalDokument55 SeitenWeek 9 - Identity Contact and Intergroup Encounters. FinalTuân NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agarwal 2009Dokument12 SeitenAgarwal 2009marufNoch keine Bewertungen

- SympathyDokument19 SeitenSympathyblazsekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attitudes and Behaviour For TEX3701 2020Dokument13 SeitenAttitudes and Behaviour For TEX3701 2020SleepingPhantomsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raimo Tuomela - Social Ontology - Collective Intentionality and Group Agents-Oxford University Press (2013)Dokument327 SeitenRaimo Tuomela - Social Ontology - Collective Intentionality and Group Agents-Oxford University Press (2013)Marco Fedro ImberganoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Needs Assessment in Mathematics Competencies of Grade 6 Completers PDFDokument8 SeitenNeeds Assessment in Mathematics Competencies of Grade 6 Completers PDFAldrin MatiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- L & M in Nursing - ConflictDokument26 SeitenL & M in Nursing - ConflictMichael SamaniegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ex The Theory of Reasoned Action-2016 Munson PDFDokument4 SeitenEx The Theory of Reasoned Action-2016 Munson PDFAlexa0% (1)

- Improving Children's Reading AttitudesDokument25 SeitenImproving Children's Reading Attitudesajitar2003Noch keine Bewertungen

- Self AwarenessDokument30 SeitenSelf AwarenessMuneeba AminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advertising: Meaning, Definition and FunctionsDokument137 SeitenAdvertising: Meaning, Definition and FunctionsDhruv DuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 MoellerDokument18 SeitenChapter 1 MoellerLuis Rosique MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employee Attitudes and Job SatisfactionDokument14 SeitenEmployee Attitudes and Job SatisfactionBobby DNoch keine Bewertungen

- Priya 2Dokument36 SeitenPriya 2gudiyaprajapati825Noch keine Bewertungen