Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1 MacDougall - Wright ICFCY and GAS 2009

Hochgeladen von

ec16043Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1 MacDougall - Wright ICFCY and GAS 2009

Hochgeladen von

ec16043Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Disability and Rehabilitation, 2009; 31(16): 13621372

REHABILITATION IN PRACTICE

The ICF-CY and Goal Attainment Scaling: Benefits of their combined

use for pediatric practice

JANETTE MCDOUGALL1 & VIRGINIA WRIGHT2

1

Research Program, Thames Valley Childrens Centre, London, Ontario, Canada and 2Research Program, Bloorview Research

Institute, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

Accepted October 2008

Abstract

Purpose. There is much heterogeneity and disconnect in the approaches used by service providers to conduct needs

assessments, set goals and evaluate outcomes for clients receiving pediatric rehabilitation services. The purpose of this article

is to describe how the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health-Child and Youth (ICF-CY) can be

used in combination with Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS), an individualised measure of change, to connect the various

phases of the therapeutic process to provide consistent clinical care that is family-centred, collaborative, well directed and

accountable.

Method. A brief description of both the ICF-CY and GAS as they pertain to pediatric rehabilitation is provided as

background. An explanation is given of how the ICF-CY offers a framework through which clients, families and service

providers can together identify the areas of clients needs. In addition, the article discusses how the use of GAS facilitates

translation of clients identified needs into distinct, measurable goals set collaboratively by clients, their families and service

providers. Examples of integrated GAS goals set for the various components of the ICF-CY are provided. The utility of GAS

as a measure of clinical outcomes for individual clients is also discussed.

Conclusions. Used in combination, the ICF-CY and GAS can serve to coordinate, simplify and standardise assessment and

outcome evaluation practices for individual clients receiving pediatric rehabilitation services.

Keywords: ICF, ICF-CY, goal attainment scaling, children, rehabilitation, disability

Introduction

Goal setting has been described as the identification

of and agreement on a target among a client, his/her

family and service provider(s) followed by working

towards the target over a specific period of time [1].

The focus of rehabilitation has recently broadened to

promote enhanced social participation, in addition to

encouraging improved physical function and better

performance in activities of daily living [2]. The

importance of improving environmental supports to

enhance client functioning has also been recently

recognised. At any one point in time, a client may

have needs that require setting goals for change

across diverse aspects of functioning, as well as for

modifications to the environment. Unfortunately,

needs are often assessed and goals set without an

overarching frame of reference that can help clients

and service providers: (a) to identify the specific

aspects of individual functioning and the environmental factors that a clients goals should target for

change, and; (b) to understand how goals are

meaningful and interrelated within the overall context of the clients life and long-term development.

Furthermore, goals are often loosely set and broadly

defined, meaning that change cannot be accurately

or sensitively measured.

Clinical observation, the use of standardised

measures, and parent, client, teacher or other service

provider reports/interviews are among the most

common approaches used by rehabilitation service

providers of various disciplines (i.e. occupational

therapists, physical therapists, speech language

pathologists, social workers, recreational therapists,

Correspondence: Janette McDougall, Research Program, Thames Valley Childrens Centre, 779 Base Line Road East, London, Ontario, N6C 5Y6 Canada.

E-mail: janettem@tvcc.on.ca

ISSN 0963-8288 print/ISSN 1464-5165 online 2009 Informa UK Ltd.

DOI: 10.1080/09638280802572973

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

The ICF-CY and GAS

behavioural therapists, nurses and others) for evaluating change in clients goal-based outcomes [3].

Both clinical observation, particularly by an expert

service provider, and reports/interviews may be quite

insightful and provide useful information for both

needs assessment and estimating change in childrens goals [4]. However, for accountability purposes, these approaches may need to be

supplemented with the use of goal setting and rating

techniques that can provide sound measurement,

and efficient documentation of client outcomes.

Standardised measures may be used to assess a

client at intake and to measure change in the clients

functional goals following service delivery. However,

standardised measures typically focus on selected

aspects of health and frequently do not include items

that directly reflect a clients unique needs and goals.

In such instances, the instrument will not be an

overly sensitive measure of change for the clients

goals. Moreover, service providers often report

modifying standardised measures to obtain an

accurate appraisal of the clients distinct situation

[5]. Unfortunately, modifying a standardised test can

seriously affect the psychometric properties of the

instrument [5]. Another issue with using standardised measures to evaluate change in clients goals is

that many are discriminative tools designed to

measure status at a single point in time and have

not been validated with respect to their ability to be

responsive to clinically important change [3,6].

In addition, up until recently few measures have

been available to assess a clients social participation

[7].

Studies have shown that, although families value

the types of functional changes typically reflected in

standardised measures, they place more value on

aspects of functioning that are not readily captured

by these types of measures, such as social participation [8,9]. In addition, standardised measures, in

general, do not facilitate a process whereby clients,

families and multiple service providers can work

collaboratively to set and evaluate childrens progress

on their goals. Research suggests that enhanced

collaboration among service providers and families

leads to positive service provider and client outcomes [10].

The purpose of this article is to describe how the

International classification of functioning, disability

and health-child and youth version (ICF-CY) [11]

can be employed by service providers in pediatric

rehabilitation practice to help clients and families

identify the needs related to all aspects of child

functioning and the environment. In addition, this

article will explain how this needs assessment process

can facilitate the collaborative setting of measurable,

individualised, functional goals using Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS), thus providing a quantifiable,

1363

reliable and valid assessment of change in individual

client outcomes following service delivery. The

article will also make clear why GAS is an ideal

individualised measurement approach to use with the

ICF-CY. Descriptions of the ICF-CY and GAS and

their utility with respect to collaborative service

delivery in pediatric rehabilitation practice are

provided below as background to each.

The ICF-CY

Published in 2001, the ICF [12] has been accepted

as the International standard for conceptualising

health and disability of people and populations and

for coding and collecting functional data [13]. It also

provides a system for coding and documenting the

impact of the social and physical environment on

human functioning. The ICF-CY, published in

October 2007 is based on the ICF, but is designed

specifically for use with children and youth and

allows more developmental aspects of functioning to

be coded. In addition, it focusses greater attention on

learning and child-specific environmental factors

[14]. The ICF and the ICF-CY classification systems

are designed for use with the long-standing international classification of diseases and related health

problems, tenth revision (ICD-10) [15] to provide a

comprehensive picture of the health of people and

populations [12]. Table I provides a list of the

chapters or domains of the ICF and the ICF-CY

and their level-one codes that are the foundation

for the proposed link with goal setting. The ICF

and ICF-CY also include more detailed codes at

levels two through four that can be used for

identifying needs and setting goals of greater

specificity.

In addition to providing classification systems, the

ICF and ICF-CY share a conceptual framework for

understanding functioning and disability that is

based on a biopsychosocial perspective of health. In

this framework, functioning is an umbrella term that

encompasses all body functions, activities and

participation. Disability is an umbrella term for

impairments, activity limitations and participation

restrictions. Impairments are defined as problems

in body function or structure; activity limitations

are difficulties a person may have in carrying out

daily activities; and participation restrictions are

problems a person may experience when involved in

life or social situations. A persons functioning and

disability, including a persons participation in life,

are depicted as arising from the interaction among

health conditions and environmental (e.g. air quality,

peer relationships, service availability) and personal

(e.g. age, gender, lifestyle, etc.) factors [12] (see

Figure 1).

1364

J. McDougall & V. Wright

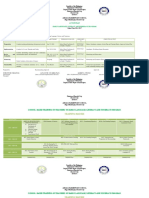

Table I. List of chapters in the ICF and ICF-CY and their levelone codes [13].

Body functions and structures

b1

b2

b3

b4

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

b5

b6

b7

b8

s1

s2

s3

s4

s5

s6

s7

s8

Mental functions

Sensory functions and pain

Voice and speech functions

Functions of the cardiovascular, hematological, immunological and respiratory systems

Functions of the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems

Genitourinary and reproductive functions

Neuormusculoskeletal and movement-related functions

Functions of the skin and related structures

Structures of the nervous system

Eye, ear and related structures

Voice and speech related structures

Cardiovascular, immunological and respiratory related

structures

Digestive, metabolic and endocrine related structures

Genitourinary and reproductive related structures

Structures related to movement

Skin and related structures

Activity and participation

d1

d2

d3

d4

d5

d6

d7

d8

d9

Learning and applying knowledge

General tasks and demands

Communication

Mobility

Self-care

Domestic life

Interpersonal relationships

Major life areas

Community, social and civic life

Natural environment and human-made changes to environment

e1

e2

e3

e4

e5

Products and technology

Natural environment

Support and relationships

Attitudes

Services, systems and policies

The ICF and ICF-CY classification systems and

shared conceptual framework are intended for use

within and across multiple sectors, such as health

promotion, rehabilitation, education, insurance, policy and statistics [16]. Within each sector, the ICF

and ICF-CY can be used for multiple purposes in

clinical (e.g. needs assessment), research (e.g. outcome measurement) and statistical areas (e.g. data

collection) [12]. However, neither the ICF nor the

ICF-CY operationalise the dimensions of disability,

that is they are not in and of themselves outcome

measures. Critical foundational work is being done

to assess the extent to which current standardised

measures capture the various domains of the ICF

[1721] and the ICF-CY [22]. In tandem with this is

the development and validation of suitable measures

of outcomes that will address measurement gaps

identified by the ICF [17]. There have also been

initiatives to assemble a selection of these measures

into a core set of outcome measures [23,24]. The

main contribution of the ICF and ICF-CY to such

efforts has been to provide an agenda of items that

should be taken into account for the development

and selection of outcome measures. Another significant use of the items included in the ICF has

been the development of core sets of items that can

be employed to generate individual profiles of

functioning for persons with various chronic conditions [25].

The extent of knowledge and practice-based

utilisation of the ICF by the providers of pediatric

rehabilitation services remains limited despite its

strong presence in the research literature [26].

However, service providers have indicated that the

ICF could be useful as a framework to guide their

practice and to facilitate collaboration with families

and other service providers. Indeed, a number of

publications have described how the ICF is starting

to be used as a framework for facilitating collaborative service delivery in pediatric rehabilitation practice [1,2734]. The ICF-CY is expected to be of

even greater relevance for this purpose than the

current ICF. Initial research has indicated that

participation and environmental factors are taken

into account more often when an assessment tool

based on the ICF-CY is used [32].

Goal Attainment Scaling

There are two main reasons for measuring outcomes

in the field of pediatric therapy: (a) to evaluate

outcomes for a specific child (to improve services to

that child); and (b) to determine the effectiveness of

a service or programme as a whole [6]. The

importance of measuring childrens progress towards

their individual functional goals is becoming increasingly recognised [35]. Individualised approaches can

demonstrate whether clients have achieved their

specific intervention goals. GAS is one of the most

widely used individualised approaches. GAS was first

developed in the 1960s by Kiresuk and Sherman [36]

and has been used to evaluate health services,

educational programmes and social services [37

39]. In the past 20 years, GAS has been used in

research work on the effects of pediatric therapy

services for children with developmental, physical

and communication needs [4050]. In those studies,

service providers of various rehabilitation disciplines

have employed GAS successfully. However, the use

of GAS for clinical purposes in pediatric practice

appears still to be limited [3,5].

GAS goals must meet six requirements. They need

to be: relevant, understandable, measurable, behavioural, attainable and time-related [51]. The GAS

procedure involves: (a) defining a unique set of goals

for each child, (b) specifying a range of possible

outcomes for each goal (on a scale recommended to

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

The ICF-CY and GAS

1365

Figure 1. The World Health Organisations model of functioning and disability [13].

contain five levels, from 72 to 2) [52] and (c)

using the scale to evaluate the childs change after a

specified intervention period. A score of 72 on a

GAS scale (typically the childs baseline level)

represents improvement that is much less than the

expected level of attainment after intervention,

71 represents improvement that is less than the

expected level of attainment after intervention, 0

represents the expected (targeted) level of attainment

after intervention and 1 and 2 represent levels of

attainment that exceed expectations but represent

outcomes that the child is thought to be capable of

achieving under extremely favourable conditions.

The aim is to have clinically equal intervals between

all scale levels.

Improvement should be measured using only one

variable of change per scale, keeping other variables

constant. If, in doing so, the goal does not remain

clinically meaningful, two (or more) variables could

change within in a single scale, provided that

improvement is not expected to occur simultaneously on these variables. For a complete description of how to write GAS goals for clients receiving

pediatric rehabilitation services, see King et al. [6].

Several key issues related to the psychometric

properties of GAS have been debated particularly

with respect to conducting programme evaluation

and research, where multivariate data analysis

techniques are used [35,53]. Although these issues

are less relevant when using GAS for clinical

purposes, a very brief discussion of its validity and

reliability follows. For a detailed discussion of using

GAS for programme evaluation purposes, see King

et al. [6], and for discussions of psychometric issues

related to GAS, see Cardillo and Smith [52,54],

Smith and Cardillo [55] and Tennant [53].

Pediatric studies provide considerable evidence of

no more than low to moderate concurrent validity

between GAS and standardised measures [6,35,48].

However, this may be advantageous when GAS is

used for clinical purposes, because GAS has been

indicated to be more sensitive to change than normreferenced measures [35]. The lack of a higher

order construct underlying GAS and the ordinal

level of measurement of GAS scales, have also been

identified as problematic [53]. Although the idiosyncratic nature of GAS may pose a threat to validity for

group comparisons, in clinical contexts, it offers an

opportunity to measure exactly what needs to be

measured [35]. Moreover, the original developers of

GAS argue that it is not the content of each specific

GAS scale that is comparable or the higher order

construct, but the perceived ability to change in a

particular domain [51]. It has been suggested that

building up item banks of goals (e.g. comparing

goals within components of the ICF), which can be

calibrated onto a unidimensional scale would allow

for an individualised yet generalisable and more

efficient approach when using GAS for group

comparisons [53].

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

1366

J. McDougall & V. Wright

GAS has been criticised due to its potential for

bias [52]. Unintentional bias can occur in goal

scaling (e.g. goals are overly easy to attain) or in goal

rating (e.g. showing that a child make improvements

that are not in fact real). Reliability can be improved,

however, by comprehensive training of service

providers with respect to goal setting and rating,

adequate definitions of the levels of goal attainment

and the use of multiple raters [38]. When carefully

implemented, inter-rater reliability of GAS between

two independent service providers rating goals on the

same occasion can be very high (ICC 0.98) [6].

Some of the processes of clinical service delivery in

pediatric settings can naturally reduce the possibility

and extent of bias in goal scaling and rating. A

collaborative goal-setting model helps to ensure that

goal areas and levels are relevant and that ratings are

valid, because both are based on a consensus

involving several individuals who are knowledgeable

about the child and invested in helping the child to

achieve real gains [5658].

Although GAS can be a time-consuming procedure, with scale development requiring up to 45 min

per child [35,59], all articles included in a review of

GAS use in pediatric rehabilitation reported high

family and service provider satisfaction with the

procedure [35]. Considering its acceptable social

validity [60] and the clinical benefits described

above, it appears to be worth the additional time

and effort and may be associated with greater

efficiency of treatment by leading to a more

streamlined, focussed intervention approach.

The combined use of the ICF-CY and GAS

It is important to note that, although the extent of

knowledge and practice-based utilisation of the ICF

and ICF-CY by rehabilitation service providers is

limited, research indicates that the types of goals set

for clients reflect ICF and ICF-CY content [3,22].

That is goals are typically set for clients across all

components of the ICF/ICF-CY (i.e. impairments,

activity limitations and participation restrictions and

environmental factors). However, service providers

tend to focus on impairment-based goals while, as

stated earlier, clients and families are more interested

in achieving goals related to activity and participation

[61]. Indeed, client goals are significantly more often

impairment or activity based than participation based

[3]. Service providers report that, even though

participation is an important outcome, it is typically

not the area that they feel is going to be immediately

influenced by the treatment they are providing [3].

As initial research suggests [32], using a needs

assessment tool based on the ICF-CY may lead to

more participation and environmental-based goals

being set for clients. Collaborative needs assessment

and goal identification using the ICF-CY can

facilitate a dialogue among clients, families and

service providers that helps to merge the two

perspectives. Moreover, because goals at the impairment and activity limitation level tend to be short

term and discipline specific, participation and

environmental-based goals may also increase as

developmental, community-based approaches to

pediatric service delivery [62] and interprofessional

collaboration [10] exert a greater influence on daily

practice.

When an initial assessment is conducted, the

domains of the ICF-CY can act as a good starting

point to help clients and families collaborate to

identify functional concerns, and can also ensure all

aspects of an individuals life are effectively addressed, as appropriate [1,32]. Visual tools [1],

developmentally structured interviews [63] or abbreviated and modified checklists similar to the ICF

checklist [64] that include a core set of codes

appropriate for use in pediatric rehabilitation settings

[27] are formats that can be used to present the ICF/

ICF-CY classification system in a manner that will

allow clients needs to be identified efficiently yet

comprehensively. Recently, developmental core

sets for four age groups have been identified from

the ICF-CY that could be useful when conducting

needs assessments for children and youth with

disabilities [65]. Some authors have provided examples of how a specific intervention-based ICF

framework model could be developed with families

during needs assessment and goal identification to

help clarify discussions about modifiable factors and

outcome possibilities across ICF (or ICF-CY)

domains [34,66] (see Figure 2 for an example of an

intervention-based model).

The ICF encourages acceptance of variation and

difference in ability, and the setting of self-defined

goals that are accomplished in whatever way is best

for each individual [32]. Once the client and his/her

family, in collaboration with rehabilitation service

providers, have identified areas requiring intervention using the ICF-CY, GAS could then be used to

transform clients broad, self-defined goals into

distinct, measurable goals.

The ICF-CY and GAS are complementary to each

other in a number of ways. Like the ICF-CY, GAS

allows for difference in ability by facilitating the

setting of goals that are unique to an individual. Also,

like the ICF-CY, GAS facilitates the assessment of

childrens development over time. Moreover, GAS

can be adapted to any ICF-CY domain [60]. Indeed,

the use of GAS allows the integration of impairment,

activity, participation or environmental goals within

the same evaluation template [3]. Goals may be

written that target change in impairment, activity

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

The ICF-CY and GAS

1367

Figure 2. Intervention-based ICF/ICF-CY framework model used to identify needs and set broad goals.

limitations or the environment as short-term goals

with change in participation as a longer-term goal

(see Table II). For example, rehabilitation service

providers (e.g. school liaison, social worker, clinician, etc.) may help a client meet the goal of

participating in school-related tasks and duties by

collaborating with the clients family and a school

team to ensure a support worker is appropriately in

place, and that the child is provided with the

necessary time to practice the functional activities

required to meet his/her participation goal.

In addition to setting short- and long-term goals

within the same evaluation template, a concurrent set

of goals could be written to permit the examination

of how changes in impairments, activity limitations

and participation restrictions are related at a given

point in time [66]. Moreover, a set of goals targeting

change in an individuals functioning and change in

the environment could be set with the same

intervention time line, and could help ascertain

how modifications to the environment impact on

child functional outcomes within that given time line

(see Table III). For example, providers of schoolbased rehabilitation services could help a client to

meet the participation goal of playing with classmates at recess by simultaneously working to

enhance the supportiveness of the social environment in the classroom for the client. This could be

done by providing information to classroom teachers

and students about disabilities, by organising classroom presentations that can help change attitudes

toward disabilities, by modelling appropriate behaviour for interacting with the client and by encouraging teachers to set up situations where the client can

come together with classmates more often (e.g.

creating learning centres that encourage interaction,

changing seating positions), all of which may

encourage child-initiated interactions at recess.

1368

J. McDougall & V. Wright

Table II. Example of goals written for different components of the ICF-CY across a time line (facilitating examination of how changes in

shorter-term goals related to the environment and activity limitations influence changes in longer-term goals related to participation).

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

Goal attainment scaling goals

Targeted ICF-CY

goal areas

Goal 1: Support from health

professionals (e355)

Goal 2: Moving around using

equipment (d465)

Goal 3: School life and related activities

(d835)

ICF-CY Component

Environmental factors

Activity limitations

Participation restrictions

Time line

1 Month

2 Months

5 Months

Level of attainment

72 (much less than

expected)

71 (somewhat less

than expected)

0 (expected level

of outcome)

1 (somewhat more

than expected)

No arrangements made for support

worker

Support worker available to work

with client h per day

Support worker available to work

with client 1 h per day

Support worker available to work

with client 1 h per day

Cannot walk with walker in

school hallway

Can walk with walker 250 m in

school hallway in 8 min

Can walk with walker 250 m in

school hallway in 6 min

Can walk with walker 250 m in

school hallway in 4 min

2 (much more

than expected)

Support worker available to work

with client 2 h per day

Can walk with walker 250 m in

school hallway in 2 min

Does not participate in hall monitoring

duties with other students at recess

Participates in hall monitoring duties for

the time at recess once a week

Participates in hall monitoring duties for

the time at recess twice a week

Participates in hall monitoring duties for

the time at recess once a week and

for entire recess once a week

Participates in hall monitoring duties for

entire recess twice a week

Comments:

If attainment falls between scale levels, goal will be rated at lower level

Table III. Example of goals written for different components of the ICF-CY with same time line (facilitating examination of reciprocal

relationship between goals targeting change in the environment and goals targeting change in child functioning).

Goal attainment scaling goals

Targeted ICF-CY

goal areas

ICF-CY Component

Goal 1: Support and relationships with

peers (e325)

Environmental factors

Goal 2: Engagement in play (d880)

Time line

5 Months

5 Months

Level of attainment

72 (much less than

expected)

71 (somewhat less

than expected)

0 (expected level

of outcome)

1 (somewhat more

than expected)

2 (much more

than expected)

Classmates do not interact* at all with

client in the classroom

Classmates interact with client once or

twice a day in the classroom

Classmates interact with client 3 times a

day in the classroom

Classmates interact with client 4 times a

day in the classroom

Classmates interact with client 5 or more

times a day in the classroom

Does not participate in child-initiated playground activities

with classmates at recess

Participates in child-initiated playground activities with

classmates at recess for about of the time on a typical day

Participates in child-initiated playground activities with

classmates at recess for about of the time on a typical day

Participates in child-initiated playground activities with

classmates at recess for about 3=4 of the time on a typical day

Participates in child-initiated playground activities with

classmates for the full recess on a typical day

Comments:

Participation restrictions

*Interaction may include any typical classroom behaviour expected between students such as: working together

on an assignment, help with completing a task, spending free time together playing a board game, etc.

If attainment falls between scale levels, goal will be rated at lower level

In addition, it is possible within a single goal to

target a variable for change at both the individual

functional level and the level of the environment

(as mentioned, GAS only allows one variable of

change per scale level, but more than one variable

can change within an entire scale) [6] (see

Table IV). This allows goals for environmental

modification to be directly linked with goals of the

client and family for functional change in the child,

thereby facilitating practice that is holistic and

family-centred [3].

When setting goals, the 0 (expected level) and

the 72 level (often the baseline) of goal attainment

should be set initially with clients (where appropriate) and their families [6]. Input at this stage from

families with respect to the other three goal levels

would also be beneficial. Service providers could

then use their GAS training and clinical expertise to

The ICF-CY and GAS

1369

Table IV. Example of a single goal that includes two variables of change.

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

Goal attainment scaling goals

Targeted ICF-CY goal areas

Goal 1: Learning to write (d145) with support from a health professional (e355)

ICF-CY Component

Activity limitations and environmental factors

Time line

6 Months

Level of attainment

72 (much less than expected)

71 (somewhat less than expected)

0 (expected level of outcome)

1 (somewhat more than expected)

2 (much more than expected)

Can

Can

Can

Can

Can

Comments:

If attainment falls between scale levels, goal will be rated at lower level

print 4 of 8 letters of first name with hands on assistance and verbal cueing

print 6 of 8 letters of first name with hands on assistance and verbal cueing

print 8 of 8 letters of first name with hands on assistance and verbal cueing

print 8 of 8 letters of first name with verbal cueing

print 8 of 8 letters of first name independently

complete the GAS scaling process. Peer review of the

scaling is also an option to enhance reliability and

validity [6]. Clients and families should then be

consulted before finalising the goal scaling. As stated,

for clinical purposes, goal rating at predetermined

review times should be undertaken as a collaborative

process between clients, families and service providers, facilitating reflection on the ongoing therapeutic process.

Some caveats

It should be made clear that it is not the authors

intention to suggest that a comprehensive ICF-CYbased initial assessment is required for all clients who

receive pediatric rehabilitation services. Often, clients are seen short term for a very specific issue (e.g.

minor speech or fine motor difficulties) that does not

necessitate an expansive ICF-CY-based assessment

at intake. In many of these cases, the evaluation

needs only to focus on the most relevant components

of the ICF-CY for that client. However, when it is

expected that a client with a complex condition will

have multiple service needs that require ongoing

intervention, a complete assessment using an ICFCY-based tool would be of great benefit.

Neither is it the authors intention to suggest that

the use of standardised measures in pediatric

rehabilitation practice should be abandoned. Indeed,

a toolbox of standardised tools should be seen as an

important part of client assessment for evaluation of

impairment and activity limitations, as these have

been found to be integral to the determination of

clients/families strengths and needs, and for setting

goals [3]. This toolbox should, whenever possible,

contain measures that have been designed for

evaluation of change [21]. Supplementation of

GAS with standardised measures that provide more

conventional estimates of post-treatment status is

also suggested to give a comprehensive assessment of

outcome, especially when evaluating outcomes for a

group of children [6,38]. For example, change at

the impairment level has been measured using a

standardised measure and then compared with

change at the participation level using GAS [67].

In addition, other individualised measures have their

own benefits for pediatric rehabilitation practice and

can provide information that differs in focus from

GAS. For example, the Canadian Occupational

Performance Measure (COPM) [68] can provide

information about a clients progress on goals in the

areas of self-care, productivity and leisure. The COPM

may be less time-consuming than GAS, and may be a

better choice when time efficiency is paramount and

clients goals fall within the three above-named areas.

GAS, however, provides complete flexibility for setting

any type of goal in any area of the ICF-CY and for

simultaneously assessing goals related to changes in

both the client and the environment.

Another option is to use components of the

COPM in combination with GAS. The COPM

provides an assessment of families satisfaction with

childrens goal attainment [3]. Used together, GAS

could provide quantifiable results on actual attainment of goals based on observable criteria

whereas the COPM could offer the clients/families

perspective on performance and its value (i.e.

satisfaction) [69].

Future considerations

In conclusion, considering the benefits, it is worth

the effort to use the ICF-CY together with GAS in

pediatric clinical practice. Given the newness of the

ICF (and ICF-CY), service providers may still lack

substantial knowledge of this framework and

classification system and few apply it in everyday

practice [26]. Therefore, pediatric centres may

first need to provide training to staff regarding the

ICF/ICF-CY. Additional information about and

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

1370

J. McDougall & V. Wright

training materials for the ICF can be accessed from

the ICFs home page [11]. Also, recent work is

available that describes three systematic programmes

for teaching service providers to use the ICF, along

with efforts to evaluate their effectiveness [70].

As stated, research indicates that providers of

pediatric rehabilitation services rarely use validated,

individualised approaches such as GAS for clinical

purposes [3,5]. Because of the lack of general

knowledge about GAS as well as the importance of

conducting the GAS procedure accurately to reduce

bias, pediatric centres interested in using GAS will

need to provide GAS training to service providers.

Specific guidelines for GAS training within the

pediatric rehabilitation context can be found in King

et al. [6].

Finally, because both the use of an ICF-CY-based

assessment tool and GAS are the added steps to the

existing therapeutic process, it is important for

managers and administrators to support the restructuring of assessment and evaluation sessions to

permit the successful integration of these procedures

into everyday practice.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Wright is supported by a Career Development

Award (2007 to 2011) through the Canadian Child

health Clinician Scientist Program, a Canadian

Institutes of Health Research Strategic Training

Initiative.

References

1. Bornman J, Murphy J. Using the ICF in goal setting: clinical

applications using Talking Mats1. Disabil Rehabil Assist

Technol 2006;1:145154.

2. Sakzewski L, Boyd R, Ziviana J. Clinimetric properties of

participation measures for 5- to 13-year old children with

cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol

2007;49:232240.

3. Wright V. From clinical observation to outcome measurement. 2007. Electronic Citation. http://www.oacrs.com/

News/Conference2007/TA7ClinicalObservationToOutcome

Measurement.ppt. Last accessed April 2008.

4. King G, Currie M, Bartlett D, Gilpin M, Willoughby C,

Tucker MA, Strachan D, Baxter D. The development of

expertise in pediatric rehabilitation therapists: changes in

approach, self-knowledge, and use of enabling and customizing strategies. Dev Neurorehabil 2007;10:223240.

5. Hanna S, Russell D, Bartlett D, Kertoy M, Rosenbaum P,

Wynn K. Measurement practises in pediatric rehabilitation: a

survey of physical therapists, occupational therapists, and

speech-language pathologists in Ontario. Phys Occup Ther

Pediatr 2007;27:2542.

6. King G, McDougall J, Palisano R, Gritzan J, Tucker MA.

Goal attainment scaling: its use in evaluating pediatric therapy

programs. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 1999;19:3152.

7. Wade D. Outcome measures for clinical rehabilitation trials:

impairment, function, quality of life, or value? Am J Phys Med

Rehabil 2003;82:S26S31.

8. Cohn E. Parent perspectives of occupational therapy using a

sensory integration approach. Am J Occup Ther 2001;55:

285294.

9. Cohn E, Miller L, Tickle-Degnen L. Parent hopes for therapy

outcomes: Children with sensory modulation disorders. Am J

Occup Ther 2000;54:3643.

10. Barrett J, Curran V, Glynn L, Godwin M. CHSRF Synthesis:

interprofessional collaboration and quality primary healthcare.

Ottawa, ON: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation;

2007.

11. World Health Organization. International classification of

functioning, disability and healthchild and youth version.

Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007.

12. World Health Organization. International classification of

functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland; 2001.

13. World Health Organization. International classification of

functioning, disability and health, Internet. Electronic Citation.

http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/site/onlinebrowser/../index.

cfm. Last accessed February 2008.

14. Lollar D, Simeonsson R. Diagnosis to function: classification

for children and youth. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2005;26:

323330.

15. World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision,

Vol 1. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992.

stun

16. Stucki G, Cieza A, Ewert T, Kostanjsek N, Chaterji S, U

T. Application of the International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) in clinical practice. Disabil

Rehabil 2002;24:281282.

17. McConachie H, Colver A, Forsyth R, Jarvis S, Parkinson K.

Participation of disabled children: how should it be characterized and measured? Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:11571164.

18. Cieza A, Brockow T, Ewert T, Amman E, Kolleritis B,

stun T, Stucki G. Linking health-status

Chatterji S, U

measurements to the International classification of functioning, disability and health. J Rehabil Med 2002;34:205210.

19. Cieza A, Stucki G. Content comparison of health-related

quality of life (HRQOL) instruments based on the International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF).

Qual Life Res 2005;14:12251237.

20. Dijkers M, Whiteneck G, El-Jaroudi R. Measures of social

outcomes in disability research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil

2000;81:S63S77.

21. Salter K, Jutai J, Teasell R, Foley N, Bitensky J, Bailey M.

Issues for selection of outcome measures in stroke rehabilitation: ICF participation. Disabil Rehabil 2005;79:506528.

22. Nijhuis B, Reindeers-Messelink H, deBlecourt A, Ties J,

Boonstra A, Groothoff J, Nakken H, Postema K. Needs,

problems, and rehabilitation goals of young children with

cerebral palsy as formulated in the rehabilitation activities

profile for children. J Rehabil Med 2008;40:347354.

23. Demers L, Desrosiers J, Ska B, Wolfson C, Nikolova R,

Pervieux I, Auger C. Assembling a toolkit to measure geriatric

rehabilitation outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005;84:

460472.

24. Rentsch H, Bucher P, Nyffeler D, Wolf C, Hefti H, Fluri E,

Wenger U, Walti C, Boyer I. The implementation of the

International classification of functioning, disability and

health (ICF) in daily practice of neurorehabilitation: an

interdisciplinary project at the Kantonsspital of Lucerne,

Switzerland. Disabil Rehabil 2003;25:411421.

stun B, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Stucji

25. Cieza A, Ewert T, U

G. Development of ICF core sets for patients with chronic

conditions. J Rehabil Med 2004;Suppl 44:911.

26. Farrell J, Anderson S, Hewitt K, Livingston M, Stewart D. A

survey of occupational therapists in Canada about their

knowledge and use of the ICF. Can J Occup Ther 2007;74:

S221S232.

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

The ICF-CY and GAS

27. McDougall J, Horgan K, Baldwin P, Tucker MA. Employing

the International classification of functioning, disability, and

health (ICF) to enhance services for children and youth with

chronic physical health conditions and disabilities. Paediatr

Child Health 2008;13:173178.

28. Campbell W, Skarakis-Doyle E. School-aged children with

SLI: the ICF as a framework for collaborative service delivery.

J Commun Disord 2007;40:513535.

29. McLeod S, Bleile K. The ICF: a framework for setting goals

for children with speech impairment. Child Lang Teach Ther

2004;20:199219.

30. Darzins P, Fone S, Darzins S. The International

classification of functioning, disability, and health can help

structure and evaluate therapy. Aust Occup Ther J 2006;53:

127131.

31. Palisano R. A collaborative model of service delivery

for children with movement disorders: a framework for

evidence-based decision making. Phys Ther 2006;86:

12951305.

kesson E.

32. Raghavendra P, Bornman J, Granlund M, Bjorck-A

The World Health Organizations International classification

of functioning, disability and health: implications for clinical

and research practice in the field of augmentative and

alternative communication. Augment Altern Commun 2007;

23:349361.

33. Rosenbaum P, Stewart D. The World Health Organization

International classification of functioning, disability and

health: a model to guide clinical thinking, practice, and

research in the field of cerebral palsy. Semin Pediatr Neurol

2004;11:510.

34. Steiner W, Ryser L, Huber E, Uebelhart D, Aeschlimann A,

Stucki G. Use of the ICF as a clinical problem-solving tool in

physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. Phys Ther

2002;82:10981107.

35. Steenbeek D, Ketelaar M, Galama K, Gorter J. Goal

attainment scaling in paediatric rehabilitation: a critical

review of the literature. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;49:

550556.

36. Kiresuk T, Sherman R. Goal attainment scaling: a general

method for evaluating comprehensive community mental

health programs. J Community Ment Health 1968;4:

443453.

37. Cytrynbaum S, Ginath Y, Birdwell J, Brandt L. Goal

attainment scaling: a critical review. Eval Q 1974;3:540.

38. Kiresuk T, Smith A, Cardillo J. Goal attainment scaling:

applications, theory, and measurement. Hillsdale, New Jersey:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994.

39. MacKay G, Somerville W, Lundie J. Reflections on goal

attainment scaling (GAS): cautionary notes and proposals for

development. Educ Res 1996;38:161172.

40. Palisano R, Haley S, Brown D. Goal attainment scaling as a

measure of change in infants with motor delays. Phys Ther

1992;72:432437.

41. Ashford S, Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment for spasticity

management using botulinum toxin. Physiother Res Int

2006;11:2434.

42. Brown D, Effgen S, Palisano R. Performance following

ability-focused physical therapy intervention in individuals

with severely limited physical and cognitive abilities. Phys

Ther 1996;78:934947.

43. Cook A, Bentz B, Lynch C, Miller B. School-based use of a

robotic arm system by children with disabilities. IEEE Trans

Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2005;13:452460.

44. Ekstrom L, Johansson E, Granat T, Carlsberg E. Functional

therapy for children with cerebral palsy: an ecological

approach. Dev Med Child Neurol 2005;47:613619.

45. King G, McDougall J, Tucker MA, Gritzan J, Malloy-Miller

T, Alambets P, Gregory K, Thomas K, Cunning D. An

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

1371

evaluation of functional, school-based therapy services for

children with special needs. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 1999;

19:529.

King G, Tucker MA, Alambets P, Gritzan J, McDougall J,

Ogilvie A, Husted K, OGrady S, Malloy-Miller T, Brine M.

The evaluation of functional, school-based therapy services for

children with special needs: a feasibility study. Phys Occup

Ther Pediatr 1998;18:127.

Oren T, Ogletree B. Program evaluation in classrooms

for students with autism: student outcomes and program

processes. Focus Autism Dev Disabil 2000;15:170175.

Palisano R. Validity of goal attainment scaling with infants

with motor delays. Phys Ther 1993;73:651658.

Steenbeek D, Meester-Delver A, Becher J, Lankhorst G. The

effect of botulinum toxin type A treatment of the lower

extremity on the level of functional abilities in children with

cerebral palsy: evaluation with goal attainment scaling. Clin

Rehabil 2005;19:274282.

Stephens T, Haley S. Comparison of two methods for

determining change in motorically handicapped children.

Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 1991;11:117.

Ottenbacher K, Cusick A. Discriminative versus evaluative

assessment: some observations on goal attainment scaling. Am

J Occup Ther 1993;47:349354.

Cardillo J, Smith A. Psychometric issues. In: Kiresuk T,

Smith A, Cardillo J, editors. Goal attainment scaling:

applications, theory, and measurement. Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp 173212.

Tennant A. Goal attainment scaling: current methodological

challenges. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:15831588.

Cardillo J, Smith A. Reliability of goal attainment scores.

In: Kiresuk T, Smith A, Cardillo J, editors. Goal attainment

scaling: applications, theory, and measurement. Hillsdale,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp 213242.

Smith A, Cardillo J. Perspectives on validity. In: Kiresuk T,

Smith A, Cardillo J, editors. Goal attainment scaling:

applications, theory, and measurement. Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp 243272.

Mitchell T, Cusick A. Evaluation of a client-centred paediatric

rehabilitation programme using goal attainment scaling. Aust

Occup Ther J 1998;45:717.

Clark M, Caudrey D. Evaluation of rehabilitation services:

the use of goal attainment scaling. Int Rehabil Med 1983;5:

4145.

Smith A. Introduction and overview. In: Kiresuk T, Smith A,

Cardillo J, editors. Goal attainment scaling: applications,

theory, and measurement. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates; 1994. pp 114.

Cusick A, McIntyre S, Novak I, Lannin N, Lowe K. A

comparison of goal attainment scaling and the Canadian

occupational performance measure for paediatric research.

Paediatr Rehabil 2006;9:149157.

Schlosser R. Goal attainment scaling as a clinical measurement technique in communication disorders: a critical review.

J Commun Disord 2003;37:217239.

Soberg H, Finsel A, Roise O, Bautz-Holtzer E. Identification and comparison of rehabilitation goals after multiple

injuries: an ICF analysis of the patients, physiotherapists,

and other allied professionals goals. J Rehabil Med 2008;

40:340346.

King G, Tucker MA, Baldwin P, LaPorta J. Bringing the life

needs model to life: implementing a service delivery model for

pediatric rehabilitation. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2006;26:

4370.

Kronk R, Ogonowski J, Rice C, Feldman H. Reliability in

assigning ICF codes to children with special health care needs

using a developmentally structured interview. Disabil Rehabil

2005;27:977983.

1372

J. McDougall & V. Wright

Downloaded By: [University of Western Ontario] At: 19:51 7 July 2009

64. World Health Organization. ICF checklist. Geneva, Switzerland; 2001.

65. Simeonsson R. ICF-CY next steps: developmental core sets.

Electronic Citation. http://apha.confex.com/alpha/134am/

techprogram/paper_130610.htm. Last accessed September

2008.

66. Wright V, Rosenbaum P, Goldsmith C, Law M, Fehlings D.

How do changes in body functions, activity, and participation

relate in children with cerebral palsy? Dev Med Child Neurol

2008;50:283289.

67. Mall V, Heinman F, Siebal A, Bertram C, Hafkemeyer U,

Wissel J, Berweck S, Haverkamp F, Nass G, Breitbach-Faller

N, Schulte-Mattler W, Korinthenberg R. Treatment of

adductor spasticity with BTX-A in children with CP: a

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Dev

Med Child Neurol 2006;48:1013.

68. Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, Opzoomer A, Polatajko H,

Pollack N. The Canadian occupational performance measure:

an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup

Ther 1990;57:8287.

69. Trombly C, Radomski M, Trexel C, Burnett-Smith S.

Occupational therapy and achievement of self-identified goals

by adults with traumatic brain injury: Phase II. Am J Occup

Ther 2002;56:489498.

70. Reed G, Dilfer K, Bufka L, Scherer M, Kotze P,

Tshivhase M, Stark S. Three model curricula for teaching

clinicians to use the ICF. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:

927941.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Chapter - 13 - Cardiovascular - Responses - Exercise Physiology For Health Fitness and PerformanceDokument32 SeitenChapter - 13 - Cardiovascular - Responses - Exercise Physiology For Health Fitness and Performanceec16043Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adding A Post-Training FIFA 11+ Exercise Program To The Pre-Training FIFA 11+ Injury Prevention Program Reduces Injury Rates AmongDokument8 SeitenAdding A Post-Training FIFA 11+ Exercise Program To The Pre-Training FIFA 11+ Injury Prevention Program Reduces Injury Rates Amongec16043Noch keine Bewertungen

- Trigger Point FinderDokument160 SeitenTrigger Point Finderec16043Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Does Best Practice Care For Musculoskeletal Pain Look LikeDokument10 SeitenWhat Does Best Practice Care For Musculoskeletal Pain Look Likeec16043Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Current Review of An Unsolved PuzzleDokument3 SeitenA Current Review of An Unsolved Puzzleec16043Noch keine Bewertungen

- DR Shahin Pourgol - Osteopathy Vs Chiropractic Vs Physical Therapy Vs Massage TherapyDokument9 SeitenDR Shahin Pourgol - Osteopathy Vs Chiropractic Vs Physical Therapy Vs Massage Therapyec16043Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2010 Handbook Survey ResearchDokument51 Seiten2010 Handbook Survey Researchec16043Noch keine Bewertungen

- Why Don't Most Runners Get Knee Osteoar... (Med Sci Sports ExercDokument2 SeitenWhy Don't Most Runners Get Knee Osteoar... (Med Sci Sports Exercec16043Noch keine Bewertungen

- Writing Lesson Plan - ZOMNIADokument5 SeitenWriting Lesson Plan - ZOMNIAJenniferHamiltonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metric System Lesson Plan 2015Dokument22 SeitenMetric System Lesson Plan 2015api-283334442Noch keine Bewertungen

- Epse 432 - Reflection PaperDokument5 SeitenEpse 432 - Reflection Paperapi-260661724Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Instructional System Design?Dokument2 SeitenWhat Is Instructional System Design?coy aslNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greek Gods Family Tree ChartDokument14 SeitenGreek Gods Family Tree ChartJohn Perseus LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action Plan Early Language, Literacy and Numeracy Program: Abkasa Elementary SchoolDokument3 SeitenAction Plan Early Language, Literacy and Numeracy Program: Abkasa Elementary Schoolenimsay somarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Real Filipino TimeDokument2 SeitenThe Real Filipino TimeMilxNoch keine Bewertungen

- V Interpretation Construction (ICON) Design ModelDokument23 SeitenV Interpretation Construction (ICON) Design ModelSakshi SadhanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation The Smart School in Malaysia'Dokument8 SeitenPresentation The Smart School in Malaysia'sha aprellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 9 The Canadian Atlas Online - WeatherDokument9 SeitenGrade 9 The Canadian Atlas Online - Weathermcmvkfkfmr48gjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Precalculus PDFDokument28 SeitenPrecalculus PDFRosanna Lombres83% (6)

- MSTA 2003 Conference ProgDokument31 SeitenMSTA 2003 Conference ProgchaddorseyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grammar - PET For SchoolsDokument10 SeitenGrammar - PET For SchoolsRuth100% (1)

- Lozanov and The Teaching TextDokument33 SeitenLozanov and The Teaching TextPhạm Thái Bảo NgọcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Percent Lesson PlanDokument1 SeitePercent Lesson Planapi-344760154Noch keine Bewertungen

- M7NS Ia 1Dokument6 SeitenM7NS Ia 1jennelyn malayno0% (1)

- Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenLesson Planapi-237655947Noch keine Bewertungen

- HCM Course HandbookDokument22 SeitenHCM Course HandbookAlex ForryanNoch keine Bewertungen

- IQ and The Problem of Social AdjustmentDokument4 SeitenIQ and The Problem of Social AdjustmentCarlos ContrerasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development Plan Rpms Sy 2018 2019Dokument8 SeitenDevelopment Plan Rpms Sy 2018 2019Gideon Salino Gasulas BunielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beaumont Job Shadow All Interview Ty NoteDokument12 SeitenBeaumont Job Shadow All Interview Ty Noteapi-358423274Noch keine Bewertungen

- Developing An Invisible Message About Relative Acidities of Alcohols in The NaturDokument4 SeitenDeveloping An Invisible Message About Relative Acidities of Alcohols in The NaturDhiman BasuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article On The Importance of Elementary EducationDokument3 SeitenArticle On The Importance of Elementary EducationNITISHSN100% (1)

- Terminal Report English Fair 2019Dokument8 SeitenTerminal Report English Fair 2019Brandy BitalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- CalculatinghalflifeDokument5 SeitenCalculatinghalflifeapi-256503273Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Models Transmission TransactionDokument3 SeitenTeaching Models Transmission TransactionMark BorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Locker GameDokument3 SeitenLocker GameYashmeeta SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 32 Q4Dokument9 SeitenWeek 32 Q4Jacquelyn Buscano DumayhagNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Fbms Tlac Strategies OverviewDokument2 Seiten2017 Fbms Tlac Strategies Overviewapi-332018399Noch keine Bewertungen

- Music of Mindoro DLLDokument2 SeitenMusic of Mindoro DLLkarla joy 05100% (1)