Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1467-6427 00228

Hochgeladen von

Fausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1467-6427 00228

Hochgeladen von

Fausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Association for Family Therapy 2002.

Published by Blackwell Publishers, 108 Cowley

Road, Oxford, OX4 1JF, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

Journal of Family Therapy (2002) 24: 423435

01634445

The family therapy journals in 2001:

a thematic review

Mark Rivetta

This article reviews the principal English-language (including British)

family therapy journals for the year 2001. Articles are clustered around

various common themes which include marital therapy and cultural

competency. There is also a discernible interest in working with populations that have received less attention from family therapists such as

substance misusers. Within this literature there is also a trend to import

ideas and methods from other therapeutic traditions. Important research

papers are noted from within these categories, rather than having a separate section. As this is the fifth in a series of reviews, a look back at trends

within the family therapy literature concludes the paper.

It is probable that in years to come the year 2001 will be judged as

the year that was nestled between the millennium and the cataclysm

of 11 September. This means that while 2002 will stand out as a year

when trauma and community tragedy dominates therapy literature,

2001 will slip from memory. This would be a shame because in many

ways 2001 seems to have embodied the continual expansion of

family therapy theory and practice. On the one hand, there was a

consolidation of crucial issues such as marital therapy and cultural

competency. On the other hand, in sometimes quite understated

ways, family therapists described using their therapy with groups of

clients that have rarely been discussed. Within this there was

another trend: to import (or reinstate) ideas from other therapies

such as person-centred therapy or motivational interviewing into

family therapy practice. The literature therefore presents a picture

of family therapists consolidating practice while engaging in subtle

experimentation.

a Family Therapist, Harvey Jones Adolescent Unit, Cardiff; Lecturer in Family

Therapy and Systemic Practice, Bristol University; Childrens Services Manager,

NSPCC Domestic Violence Prevention Service, 44 The Parade, Roath, Cardiff,

Wales, CF24 3AB. E-mail: markrivett@beeb.net

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

424

Mark Rivett

Couples therapy

The year 2001 saw a substantial expansion in articles that sought to

increase family therapists knowledge of couples therapy. For the

purposes of this review I will categorize these articles into two types:

ones which provided a feminist perspective on couples work and

those which sought to integrate other theoretical ideas into this

work.

Vatcher and Bogo (2001) provide a thoughtful practice model

for couples therapy which fuses feminist and emotion focused therapy. They argue that their method recognizes that both men and

women possess a strong, inherent drive to be connected and experience interdependence with intimate others (2001: 70). More

specifically they argue that many young couples presenting for

therapy today are struggling precisely with issues of shifting, contradictory gender roles. The presenting problem is gender (2001: 72).

Later they assert that heterosexual couplehood today is a mess of

contradictions (2001: 75) which is why they have constructed a

therapy that integrates the advantages of emotion focused therapy

with feminist insights. The therapy they outline moves through various stages, including delineating couple conflict (which revolves

around gender roles), noting negative interactional cycles, discovering unacknowledged emotions, and reframing conflict in terms

of attachment needs. The outcome is to move into a stage in which

each partner accepts the other partners needs and new interactional patterns are created.

Other articles address issues of couples facing challenges such

as gay relationships in which one partner is HIV positive (Palmer

and Bor, 2001), interracial couple relationships (Killian, 2001), and

divorced fathers alienation from their children (Vassiliou and

Cartwright, 2001). However, as in other years, domestic violence is

where the challenge of and the feminist perspective on couples

therapy came together most keenly. On this issue 2001 saw some

repetition of previous skilful couples therapy where domestic

violence has occurred, but also a return to an earlier controversy.

Vetere and Cooper (2001) described a unique project that works

with couples where the man has previously assaulted the woman.

This project is contracted to undertake the therapy either by the

courts or childcare agencies. In this regard the service adds a fuller

systemic approach to the work with family violence from the

Ackerman Institute (Goldner et al., 1990), an approach commented

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Family therapy journals in 2001: a review

425

on by Rivett (2001). However, Hunter (2001) highlighted the

controversies surrounding this issue more fully in a special section

in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy by describing the ethical dilemmas family therapists face in dealing with

domestic violence. She challenges person-centred, feminist, Milan,

post-Milan and narrative therapists alike to acknowledge the ethical

consequences of their form of therapy. For example, she comments

that the main ethical dilemma for the narrative therapist. . . would

be how to work within the legal limitations on confidentiality. . .and

maintain engagement with the clients (2001: 85).

In some senses, Hunters article prepares the ground for the

more radical article by Watson (2001). Watson provides a thoroughgoing critique of the notion that patriarchy is the fundamental cause of domestic violence and that only one form of practice

flows from this analysis. He argues that the perspective that patriarchy causes domestic violence means that: poverty, substance

abuse and compound disadvantage are dismissed (2001: 92).

Moreover, Watson suggests that this one-dimensional understanding of domestic violence (which he regards as feminist inspired) has

silenced other approaches. As a result he calls for diversity in the

field: adequate research into the many forms of intervention.

Goldner (2001) herself provides a commentary upon Watsons

article. In this (true to her own axiom of both/and) she both

agrees with his call for diversity and also reasserts the value of the

feminist perspective. The latter is the fundamental ethical and

political framework, but once this is established there should be

room for many voices and approaches to this grave and complex

problem. Innovation should not be treason (2001: 96). Within this

measured approach to understanding domestic violence, S.

Anderson (2001) contributes a paper that explores the use of assessment measures with couples in which violence has occurred.

The second theme which suffused the couples therapy literature

in 2001 was that of integrating therapeutic methods from other

traditions. The predominant addition was the importing of motivational interviewing (Miller and Rollnick, 1991) although

Middelberg (2001) also provided an excellent description of the

value of projective identification in couples therapy. Rohrbaugh et

al. (2001) adapted motivation interviewing for work with changeresistant smoking. The thesis of their work was that individuals who

fail to alter smoking habits even when their health is at risk are

often caught up in interactional cycles that perpetuate the smoking.

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

426

Mark Rivett

The authors argue that these cycles may be categorized into ironic

processes in which a partners attempts to stop the smoking merely

encourage it. Family therapists would describe this pattern as more

of the same ( la Palo Alto). The other pattern is one where the

symptom fits the system. Rohrbaugh et al. state: smoking can serve

relational functions such as regulating emotional expression and

interpersonal closeness (2001: 21). The authors then apply this

understanding of smoking to a couples intervention model in

which they combine family therapy methods, motivational interviewing (to raise investment in change) and solution-focused questions.

Cordova et al. (2001) also describe adapting motivational interviewing in couples work, but they are interested to see if this

method can be applied as a form of distress prevention strategy.

They argue that only couples who have reached a major crisis will

attend for marital therapy, and thus apart from marital enrichment

programmes, therapists are unable to intervene at the most appropriate moment. Accordingly, they have constructed a Marriage

Checkup intervention. This provides free expert information

about the state of a couples relationship and is based upon the

principles of motivational interviewing (Miller and Rollnick, 1991).

Cordova and his colleagues aim to provide information in a way that

increases motivation for change and carefully nudges couples into

recognizing that they are having difficulties. Their paper reports

that their approach does indeed attract pre-crisis couples who

then appear to have improved relationships even after such a

limited intervention.

Cultural competency

As in other years, articles about cultural competency may be divided

into those that seek to increase knowledge about diverse groups, and

those that stimulate self-reflexivity about diversity. Foremost among

those articles that increased knowledge were a number which highlighted the role of therapy with refugee families. Within the latter

section, 2001 saw a number which researched family therapists attitudes and experiences of cultural competency.

In the first of two papers published in 2001, Sveaass and Reichelt

(2001a) discussed the difficulties encountered when refugee families are referred for therapy. Essentially the authors argue that the

culturally competent therapist must attend to the referral context

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Family therapy journals in 2001: a review

427

(e.g. how the thinking of the referrer relates to the thinking of the

family) before embarking upon therapy. In this way therapy can be

both respectful and coherent with the families own perceptions of

their needs. In the second paper the same authors (Sveaass and

Reichelt, 2001b) describe involving the referrer in the first family

consultation in order to clarify the views of both family and referrer.

Woodcock (2001: 138) also provided a thoughtful description of the

therapeutic work at the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims

of Torture. He stated that:

the pre-eminent need of survivors who seek therapeutic help is for a

psychotherapeutic framework that is broadly based and as inclusive as

possible. This will facilitate the emergence of multiple stories that will

enable the reconstruction of their worlds.

The approach that Woodcock therefore outlines is one in which

narrative, psychoanalytical and systemic perspectives are melded into

a whole that also retains a sociopolitical stance. One of the most interesting aspects of Woodcocks paper is that he attends to the therapists experience of listening daily to stories of torture, violence and

sexual abuse. Again he suggests that psychoanalytical approaches may

be helpful in enabling therapists to manage these stories.

Among other articles which considered cultural competency with

specific cultural groups were a number that addressed the needs of

Indian families (Dugsin, 2001; Wali, 2001). However, Khisty (2001)

used her experience as an Indian woman in Australia to reflect

upon how members from one culture connect to a host culture.

Khisty talks about the subtle personal changes that she underwent

when she moved to Australia: Social dilemmas centred on whether

one ought to relate with the Australian politeness or continue

behaving in a way consistent with the typically Indian practice.

Indians stopped behaving like Indians (2001: 19). She gives an

example of being invited out for a meal to another Indians house:

Should one take a bottle of wine along? (as in Australian culture)

or not (as fits the relationship between host and guest within Indian

culture)? Out of the discussions about how therapists can acknowledge and work with these differences, Khisty recommends a transcultural approach because trans implies being beyond both (or

indeed all) cultures. Her premise is that when individuals migrate,

the process of change can be variable but inevitable: in cultural

transition. . .all individuals are continually being transformed

(2001: 23). Moreover, these families are themselves new and cannot

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

428

Mark Rivett

be explained by any cultural stereotype. Nor do the terms assimilation or integration match their experiences.

The second theme within the cultural competency literature in

2001 was one of reflection and research about how competent

family therapists really are. Constantine et al. (2001) surveyed 200

American marital and family therapists in order to assess the interconnection between therapists white racial identity and their views

of their competence in working multiculturally. Interestingly, they

found that therapists reported more confidence in working in a

multicultural society if they had attended relevant courses. Yet a

higher number of courses did not create more confidence! The

authors speculate that this is because such courses emphasize

knowledge, not self-awareness. This would complement the other

finding that a strong white racial identity translated into feeling

incompetent in multicultural work.

Nelson et al. (2001) conducted a different study that relied upon

a qualitative methodology to explore views about ethnicity in family

therapy. They interviewed twenty-nine leading family therapists

and asked them questions ranging from the importance of ethnicity to the process of therapy to what do training programmes need

to do in order to train culturally competent therapists. Their findings were that there are diverse and often contradictory perspectives in the field on this issue. Indeed, they subdivide the sample

into those who responded mostly about the effect of ethnicity upon

therapists, and those who responded about ethnicity affecting the

clients. They also noted that one group of therapists believed in

focusing on ethnicity during therapy, while another group

preferred a global view about diversity practice. These papers

constitute the start of empirical studies that will surely provide more

knowledge about cultural competency in the years to come.

Working with neglected client groups

As noted earlier, in 2001, family therapists addressed working with

a number of client groups that have not been well represented in

previous years. There were, for instance, some articles that

described a solution-focused approach to childhood disability

(Coles, 2001) and a multi-systemic approach to families where one

member has a learning disability (Trimble, 2001). It was however in

the literature related to substance misuse that the family therapy

journals really blossomed.

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Family therapy journals in 2001: a review

429

In this area, the full creativity and diversity of systemic practice

was truly shown in the way that our tradition does so well. In this

case the diversity was founded upon a solid review of the field by

Rotunda and Doman (2001). They discussed the evidence for the

terms enabling and co-dependency when applied to relationships

between substance misusing individuals and their families. Overall,

they reject the term co-dependency, since it replicates traditional

pathological attitudes to women, extends the disease model to the

whole family and confuses causes with consequences (of substance

misuse). The authors comment that:

The popular notion that spouses of alcoholics possess personality traits

that cause them to exhibit irrational enabling behaviours has been abandoned. . .and replaced with the view that enabling behaviours are normal

reactions to the stress that is present in the alcoholic family.

(Rotunda and Doman, 2001: 260)

The most interesting outcome of this review of research was that it

suggests that even working alone with the partner of a substance

misusing individual can make a difference to the level of misuse

engaged in by that individual. Ultimately, the review provides

further evidence that there are interactional sequences that can be

changed by systemic therapy but that further study is needed to

understand partner responses to addiction (2001: 267).

From this foundation, practitioners explored a number of methods of working and a number of groups to work with. Trute et al.

(2001) researched couples therapy for women who were in addictions recovery and who were also survivors of childhood sexual

abuse. They found that the men and women had different needs

from treatment at this point. The men needed to learn how to deal

with their partners anger and address their view that their partner

was a wounded person, while the women needed to find ways of

containing and dissipating their anger and to translate the gains

they had made individually into relationship gains with their male

partners. Nevertheless, their trial suggested that quite brief conjoint

therapy during an addictions recovery programme significantly

improved the relationship context for the woman.

Other authors also provided extensive descriptions of services

they offered families in which a member misused substances.

Bamberg et al. (2001) concentrated upon group therapy with

parents of substance misusing adolescents. This team offer a structured programme of nine meetings in which a combination of

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

430

Mark Rivett

education and therapy occurs. The topics of the meetings ranged

from encouraging self-management and responsibility to individualised family strategies. They comment that in this work there are

three main steps which are:

[to] ensure appropriate care for the parent. . .[to] ensure working parental

relationships. . .[and] young people must be challenged and encouraged

to establish responsible and reciprocal adultadult relationships.

(Bamberg et al., 2001: 197)

Pichot (2001) on the other hand gave a thorough clinical and

research analysis of a solution-focused approach. This, like other

approaches mentioned above, borrowed methods such as motivational interviewing and intergrated them into a solution-focused

group work programme. Pichot (2001) provides a wealth of audit

evidence to show that this method is effective with a range of

substance misusers and particular emphasis is given to the effectiveness with child protection referrals. One clinical exercise he

described might have general usefulness. This is the idea of an

Emergency Roadside Repair Kit (2001: 13). This technique is

designed to help clients prepare for relapses and consists of, first,

describing the repair kit needed for a car. Second, using that

metaphor, clients are encouraged to describe a repair/relapse kit

that they can carry in their heads in the eventuality of difficulties

recurring.

From Britain, Vetere and Henley (2001) also gave a valuable

description of their own systemic work within a community alcohol

service. This displayed the skill that some systemic therapists have in

working alongside other interventions and indeed in integrating

the systemic model with treatment regimens based on other

perspectives. Working within a stages of change model (which

itself is becoming more widely debated within family therapy circles

see Prochaska, 1999), the authors describe how family therapy can

contribute

to the management of relapse. . .by offering support and helping to think

through and problem-solve around the effects of relapse on relationships,

communication and functioning throughout the family.

(Vetere and Henley, 2001: 89)

They note how complex motivation might be for both the drinker

and their family and they chart the various forms of systemic work

they might do at different stages of the change process. Thus in

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Family therapy journals in 2001: a review

431

initial stages the authors offer a form of consultation and would

only embark upon couple therapy when the clients think it is right

for them.

Importing from other schools

If traditions of psychotherapy can be compared to religions, they

may also be divided into those which adapt to the culture in which

they find themselves, and those which retain their purity. It has

always seemed to me that family therapy and systemic practice are

therefore more like Hinduism than Christianity: they evolve during

conversations with the outside world rather than during conversations with themselves. In previous sections I have highlighted some

of the imports from other traditions (e.g. motivational interviewing). But 2001 was also the year when these conversations included

the work of Carl Rogers. In these conversations, Rogers was seen as

a precursor to postmodern therapies. Harlene Anderson (2001),

herself an eminent exponent of collaborative approaches, led this

discussion. She described the humanistic and existential roots of

Rogers therapy and made connections between these and her own

postmodern collaborative practice. In particular Anderson noted

Rogers scepticism about there being one kind of reality (2001:

346) and his preference for a therapy that respected a pace,

purpose and outcome determined by the client. She also equated

her thoughts about the therapist not knowing with Rogers dislike

of advice-giving in therapy. In fact this paper by Anderson is possibly the most eloquent definition of what she means by not knowing. Having described the similarities between her practice and

that of person-centred practice, Anderson accepts that there are

differences. These may be summed up, she says, by concentrating

on the therapist intention, goal of therapy and the process of therapy (2001: 356).

Bott (2001), on the other hand, examines the difficulties in

applying Rogers approach to family therapy. He comments that the

postmodern turn in family therapy has been an attempt to humanize the field but a return to Rogers could also do this. However, the

stumbling-block has always been how to apply person-centred ideas

to conjoint work. Botts paper is a valuable theoretical review that

attempts to address this stumbling-block. His conclusion is that

actually many of the person-centred concepts are taken for granted

within family therapy:

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

432

Mark Rivett

these [Rogers humanistic principles] are embedded within the practice of

family therapy, they remain largely unacknowledged, and are thus underdeveloped within a systemic framework.

(Bott, 2001: 375)

Walkers article however sets out to provide a practical application

of the Rogerian perspective in postmodern psychotherapy (2001:

41). He thus delineates Rogers methods of reflection, empathy,

using silences, accepting negative experiences and agreeing to various interpretations. He then describes these as equally postmodern

methods. Walker gives examples from transcripts from Rogers

work and, although seeking to collaborate with the Rogerian

tradition, at times he almost claims that postmodern approaches

are better. For instance, he says that: modernist empathy is a

technical means to some ends. Postmodern empathy is an end in

itself (2001: 44).

McGoldrick and Carter (2001) also contributed a paper in 2001

which sought to outline a systemic approach with single individuals.

Here they drew more upon Bowens ideas than Rogers, but equally

seemed to be pulling in ideas from outside the family therapy field

to describe their kind of coaching with an individual. They define

this form of individual work as aiming to: help the client define his

or her own beliefs and life goals, rather than just accepting the

family or the cultures values unthinkingly or reacting against them

(2001: 282). They note that: coaching is usually done with the most

motivated and functional family member, rather than the most

symptomatic, because this is the person most able to take action to

change his or her part in the family process (2001: 282).

McGoldrick and Carter then provide the stages they undertake

when coaching an individual. They help the person understand the

family system in which they are located, and the system in which

they grew up. They then help the person establish his or her goals

in terms of these systems, and they construct interventions to help

the person achieve these goals. All in all their paper reads like a

return to some older ideas: ones that are often suppressed within

family therapy literature currently.

A summing up: the past five years

This thematic review is the fifth of its kind, and the final one undertaken under the current editor. In this final section, I therefore

want to reflect upon the trends in the journals that I have noticed

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Family therapy journals in 2001: a review

433

over the past five years. What has continued is that each journal has

its own niche, and it is also noticeable that there is a clear split

between the research-orientated papers and practice papers.

Indeed, over the past five years the output of research appears to be

growing in all the journals. Within the practice papers some abiding themes predominate: cultural competency, domestic violence

and gender. Overall, it would seem that there has been a decline in

articles that are inspired by postmodernism, and with that decline

there has been a rise in papers that try to integrate the lessons from

postmodernism. This year, for instance, Linares (2001) argued for

an ultramodern family therapy. The division between research and

clinical knowledge in particular brings the need for this integration

more into focus. What continues to be outstanding is the breadth

and creativity of practice that resides in the systemic therapy field.

Each of these reviews of the literature stands as testament to this

breadth and creativity. Out of this diversity, sometimes controversy

erupts: for example, Minuchins (1998) disagreements with the

postmodern therapies and Johnsons (2001) strong criticisms of the

Messianic tendencies in family therapy. Over the next five years,

we may expect this diversity to continue. We may also expect the

empirical aspects of our field to become more significant as

evidenced-based practice becomes more accepted. Where the

controversies will come from we will have to wait and see.

References

Anderson, H. (2001) Postmodern collaborative and person-centred therapies:

what would Carl Rogers say? Journal of Family Therapy, 23: 339360.

Anderson, S. (2001) Clinical evaluation of violence in couples: the role of assessment instruments. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 12: 118.

Bamberg, J., Toumbourou, J., Blyth, A. and Forer, D. (2001) Change for the BEST:

family changes for parents coping with youth substance abuse. Australian and

New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 22: 189198.

Bott, D. (2001) Client-centred therapy and family therapy: a review and commentary. Journal of Family Therapy, 23: 361377.

Coles, D. (2001) The challenge of disability: being solution focused with families.

The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 22: 98104.

Constantine, M., Heather, J. and Liang, J. (2001) Examining multicultural counseling competence and race-related attitudes among white marital and family

therapists. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27: 353362.

Cordova, J., Warren, L. and Gee, C. (2001) Motivational interviewing as an intervention for at-risk couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27: 315326.

Dugsin, R. (2001) Conflict and healing in family experience of second-generation

emigrants form India living in North America. Family Process, 40: 233241.

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

434

Mark Rivett

Goldner, V. (2001) Why such fear of complexity? The Australian and New Zealand

Journal of Family Therapy, 22: 9697.

Goldner, V., Penn, P., Sheinberg, M.S. and Walker, G. (1990) Love and violence:

gender paradoxes in volatile relationships. Family Process, 29: 343364.

Hunter, S. (2001) Working with domestic violence: ethical dilemmas in five theoretical approaches. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 22:

8089.

Johnson, S. (2001) Family therapy saves the planet: Messianic tendencies in the

family systems literature. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27: 312.

Khisty, K. (2001) Transcultural differentiation: a model for therapy with ethnoculturally diverse families. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family

Therapy, 22: 1724.

Killian, K. (2001) Crossing borders: race, gender, and their intersections in interracial couples. Journal of Feminist Therapy, 13: 131.

Linares, J. (2001) Does history end with postmodernism? Toward an ultramodern

family therapy. Family Process, 40: 401412.

McGoldrick, M. and Carter, B. (2001) Advances in coaching: family therapy with

one person. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27: 281300.

Middelberg, C. (2001) Projective identification in common couple dances. Journal

of Marital and Family Therapy, 27: 341352.

Miller, W. and Rollnick, S. (1991) Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to

Change Addictive Behaviour. New York: Guilford Press.

Minuchin, S. (1998) Where is the family in narrative family therapy? Journal of

Marital and Family Therapy, 24: 397403.

Nelson, K., Brendel, J., Mize, L., Hancock, C., Lad, K. and Pinjala, A. (2001)

Therapist perceptions of ethnicity issues in family therapy: a qualitative inquiry.

Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27: 363373.

Palmer, R. and Bor, R. (2001) The challenges to intimacy and sexual relationships

for gay men in HIV serodiscordant relationships: a pilot study. Journal of Marital

and Family Therapy, 27: 419431.

Pichot, T. (2001) Co-creating solutions for substance abuse. Journal of Systemic

Therapies, 20: 123.

Prochaska, J. (1999) How do people change and how can we change to help

people? In M. Hubble, B. Duncan and S. Miller (eds), The Heart and Soul of

Change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rivett, M. (2001) Comments Working systemically with family violence:

controversy, context and accountability. Journal of Family Therapy, 23:

397404.

Rohrbaugh, M., Shoham, V., Trost, S., Muramoto, M., Cate, R. and Leischow, S.

(2001) Couple dynamics of change resistant smoking: toward a family consultation model. Family Process, 40: 1531.

Rotunda, R. and Doman, K. (2001) Partner enabling of substance use disorders:

critical review and future directions. American Journal of Family Therapy, 29:

257270.

Sveaass, N. and Reichelt, S. (2001a) Refugee families in therapy: from referrals to

therapeutic conversations. Journal of Family Therapy, 23: 119135.

Sveaass, N. and Reichelt, S. (2001b) Refugee families in therapy: exploring the

benefits of including referring professionals in first family interviews. Family

Process, 40: 95114.

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Family therapy journals in 2001: a review

435

Trimble, D. (2001) Making sense in conversations about learning disabilities.

Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27: 473486.

Trute, B., Docking, B. and Hiebert-Murphy, D. (2001) Couples therapy for women

survivors of child sexual abuse who are in addictions recovery: a comparative

case study of treatment process and outcome. Journal of Marital and Family

Therapy, 27: 99110.

Vassiliou, D. and Cartwright, G. (2001) The lost parents perspective on parental

alienation syndrome. American Journal of Family Therapy, 29: 181191.

Vatcher, C-A. and Bogo, M. (2001) The feminist/emotionallly focused therapy

practice model: an integrated approach for couple therapy. Journal of Marital

and Family Therapy, 27: 6983.

Vetere, A. and Cooper, J. (2001) Working systemically with family violence: risk,

responsibility and collaboration. Journal of Family Therapy, 23: 378396.

Vetere, A. and Henley, M. (2001) Integrating couples and family therapy into a

community alcohol service: a pantheoretical approach. Journal of Family Therapy,

23: 85101.

Wali, R. (2001) Working therapeutically with Indian families within a New Zealand

context. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 22: 1017.

Walker, M. (2001) Practical applications of the Rogerian perspective in postmodern psychotherapy. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 20: 4157.

Watson, G. (2001) A critical response to the Keys Young Report. Australian and New

Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 22: 9095.

Woodcock, J. (2001) Threads from the labyrinth: therapy with survivors of war and

political oppression. Journal of Family Therapy, 23: 136154.

2002 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- 16-Week Harvey Walden MarathonTraining PlanDokument18 Seiten16-Week Harvey Walden MarathonTraining PlanKaren MiranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- 2019 SEATTLE CHILDREN'S Hospital. Healthcare-Professionals:clinical-Standard-Work-Asthma - PathwayDokument41 Seiten2019 SEATTLE CHILDREN'S Hospital. Healthcare-Professionals:clinical-Standard-Work-Asthma - PathwayVladimir Basurto100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hypothesis As Dialogue: An Interview With Paolo BertrandoDokument12 SeitenThe Hypothesis As Dialogue: An Interview With Paolo BertrandoFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk Assessment Questions and Answers 1624351390Dokument278 SeitenRisk Assessment Questions and Answers 1624351390Firman Setiawan100% (1)

- Disarming Jealousy in Couples Relationships: A Multidimensional ApproachDokument18 SeitenDisarming Jealousy in Couples Relationships: A Multidimensional ApproachFausto Adrián Rodríguez López100% (2)

- Excerpt From Treating Trauma-Related DissociationDokument14 SeitenExcerpt From Treating Trauma-Related DissociationNortonMentalHealth100% (3)

- TinnitusDokument34 SeitenTinnitusHnia UsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Systemic About Systemic Therapy? Therapy Models Muddle Embodied Systemic PRDokument17 SeitenWhat Is Systemic About Systemic Therapy? Therapy Models Muddle Embodied Systemic PRFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Presence of The Third Party: Systemic Therapy and Transference AnalysisDokument18 SeitenThe Presence of The Third Party: Systemic Therapy and Transference AnalysisFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospital NG Subic (Chapter 1)Dokument43 SeitenHospital NG Subic (Chapter 1)Nicole Osuna DichosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reducing Reactive Aggression in Schoolchildren Through Child, Parent, and Conjoint Parent-Child Group Interventions - An Efficacy Study of Longitudinal OutcomesDokument20 SeitenReducing Reactive Aggression in Schoolchildren Through Child, Parent, and Conjoint Parent-Child Group Interventions - An Efficacy Study of Longitudinal OutcomesFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applying Resistance Theory To Depression in Black WomenDokument14 SeitenApplying Resistance Theory To Depression in Black WomenFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taking It To The Streets Family Therapy andDokument22 SeitenTaking It To The Streets Family Therapy andFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relationships, Environment, and The Brain: How Emerging Research Is Changing What We Know About The Impact of Families On Human DevelopmentDokument12 SeitenRelationships, Environment, and The Brain: How Emerging Research Is Changing What We Know About The Impact of Families On Human DevelopmentFausto Adrián Rodríguez López100% (1)

- Eia Asen: Multiple Family Therapy: An OverviewDokument14 SeitenEia Asen: Multiple Family Therapy: An OverviewFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1467-6427 00198Dokument14 Seiten1467-6427 00198Fausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dental Trauma - An Overview of Its Influence On The Management of Orthodontic Treatment - Part 1.Dokument11 SeitenDental Trauma - An Overview of Its Influence On The Management of Orthodontic Treatment - Part 1.Djoka DjordjevicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Omics Research Ethics ConsiderationsDokument26 SeitenOmics Research Ethics ConsiderationsAndreea MadalinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fun Games - 1 Min Game 01Dokument9 SeitenFun Games - 1 Min Game 01Purvi ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vieillard-Baron2018 Article DiagnosticWorkupEtiologiesAndMDokument17 SeitenVieillard-Baron2018 Article DiagnosticWorkupEtiologiesAndMFranciscoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The WTO and Developing Countries: The Missing: Link of International Distributive JusticeDokument395 SeitenThe WTO and Developing Countries: The Missing: Link of International Distributive JusticeMuhammad SajidNoch keine Bewertungen

- CrimPro Cases People Vs LlantoDokument7 SeitenCrimPro Cases People Vs LlantoFatmah Azimah MapandiNoch keine Bewertungen

- X Ray Diffraction Safety InformationDokument48 SeitenX Ray Diffraction Safety Informationrenjith2017100% (1)

- Ewald Hecker's Description of Cyclothymia As A Cyclical Mood Disorder - Its Relevance To The Modern Concept of Bipolar IIDokument7 SeitenEwald Hecker's Description of Cyclothymia As A Cyclical Mood Disorder - Its Relevance To The Modern Concept of Bipolar IItyboyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lepage Job WRKSHP 10-26-11Dokument2 SeitenLepage Job WRKSHP 10-26-11Andi ParkinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Skills FairDokument4 SeitenNursing Skills Fairstuffednurse100% (1)

- A Report - Noise Pollution in Urban AreasDokument14 SeitenA Report - Noise Pollution in Urban AreasArjita SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.3.1 The Autopsy-1Dokument4 Seiten1.3.1 The Autopsy-1Alyssa robertsNoch keine Bewertungen

- LlageriDokument8 SeitenLlageriBlodin ZylfiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical Manual: RTS Automatic Transfer SwitchDokument28 SeitenTechnical Manual: RTS Automatic Transfer SwitchKrīztīän TörrësNoch keine Bewertungen

- SDS N 7330 NorwayDokument15 SeitenSDS N 7330 NorwaytimbulNoch keine Bewertungen

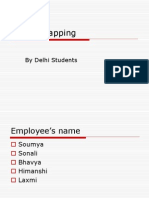

- Talent MappingDokument18 SeitenTalent MappingSoumya RanjanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study On Consumer Behavior For Pest Control Management Services in LucknowDokument45 SeitenStudy On Consumer Behavior For Pest Control Management Services in LucknowavnishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pe2 Lasw11w12Dokument4 SeitenPe2 Lasw11w12christine mae picocNoch keine Bewertungen

- IEEE Guide To The Assembly and Erection of Concrete Pole StructuresDokument32 SeitenIEEE Guide To The Assembly and Erection of Concrete Pole Structuresalex aedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ada 2018Dokument174 SeitenAda 2018CarlosChávezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action PlanDokument3 SeitenAction PlanApollo Banaag-Dizon100% (1)

- Lights and ShadowsDokument5 SeitenLights and Shadowsweeeeee1193Noch keine Bewertungen

- Food Data Chart - ZincDokument6 SeitenFood Data Chart - Zinctravi95Noch keine Bewertungen

- ID Virus Avian Influenza h5n1 Biologi Molek PDFDokument13 SeitenID Virus Avian Influenza h5n1 Biologi Molek PDFArsienda UlmafemaNoch keine Bewertungen