Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

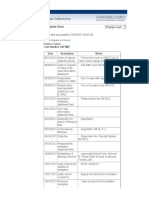

Mail & Wire Fraud Elements - 18 USC 1341-1343 Federal Criminal Law - US District Courts - United States Attorney California - United States Code - Mail Fraud - Wire Fraud - RICO Racketeering

Hochgeladen von

California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Mail & Wire Fraud Elements - 18 USC 1341-1343 Federal Criminal Law - US District Courts - United States Attorney California - United States Code - Mail Fraud - Wire Fraud - RICO Racketeering

Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

8:1. Federal mail and wire fraud statutes, 1 White Collar Crime 8:1 (2d ed.

1 White Collar Crime 8:1 (2d ed.)

White Collar Crime

Database updated June 2011

Joel Androphy

Chapter 8. Substantive Law: Mail Fraud, Wire Fraud

I. Fraud Statutes

References

8:1. Federal mail and wire fraud statutes

Wests Key Number Digest

Wests Key Number Digest, Postal Service

35(1)

Wests Key Number Digest, Telecommunications

1014(1)

A.L.R. Library

Federal Criminal Prosecutions Under Wire Fraud Statute (18 U.S.C.A. 1343) for Use of Blue Box or

Similar Device Permitting User to Make Long-Distance Telephone Calls Not Reflected on Companys

Billing Records, 34 A.L.R. Fed. 278

Law Reviews and Other Periodicals

Disgorgement in 13 Enforcement, Wire Fraud Charges and Compliance Under FCPA Provisions, 15 No.

5 Bus. Crimes Bull. 7 (January, 2008)

Additional References

Corporate Counsels Guide to White-Collar Crime 2:2

The federal mail fraud statute1 is a powerful tool employed by prosecutors against a litany of crimes.2 The statute

has undergone considerable changes as both the Supreme Court3 and Congress4 have sought to redefine it.

The mail fraud statute provides in pertinent part:

Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or artifice to defraud for the purpose

of executing such a scheme or artifice or attempting to do so, [uses or causes the mails to be used],

shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both. If the violation

affects a financial institution, such person shall be fined not more than $1,000,000 or imprisoned not

more than 30 years, or both.5

The wire fraud statute similarly provides:

Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or artifice to defraud for the purpose

of executing such scheme or artifice, [uses or causes the wires to be used in interstate or foreign

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:1. Federal mail and wire fraud statutes, 1 White Collar Crime 8:1 (2d ed.)

commerce], shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both. If the

violation affects a financial institution, such person shall be fined not more than $1,000,000 or

imprisoned not more than 30 years, or both.6

It is important to note, however, that a mailing or wire performed by a government agent solely for the purpose of

manufacturing federal jurisdiction will not support a mail or wire fraud prosecution.7 Additionally, the Supreme

Court has limited the applicability of the fraud statutes in some respects.

For example, in Cleveland v. United States, the Court held that the mail fraud statute does not reach fraud in

obtaining a statute or municipal license because a license is not property in the government regulators

hands.8

The Court reasoned that the original impetus behind the mail fraud statute was to protect the people from

schemes to deprive them of their money or property [e]quating the issuance of licenses or permits with

deprivation of property would subject to federal mail fraud prosecution a wide range of conduct traditionally

regulated by state and local authorities.9 As a result, the Court held that absent a clear Congressional mandate, it

would not read the statute to place conduct traditionally policed by the States under federal control.10

Westlaw. 2011 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. U.S. Govt. Works.

Footnotes

1

18 U.S.C.A. 1341.

2

In 2004, the Justice Department decided to take a more aggressive approach in prosecuting fraud under the

internal revenue laws. The Tax Division may now use mail fraud or wire fraud charges against an

individual who used the mails or wires either to file multiple fraudulent tax returns seeking tax refunds or

to promote fraudulent tax schemes.

McNally v. U.S., 483 U.S. 350, 107 S. Ct. 2875, 97 L. Ed. 2d 292, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P

6663 (1987) superseded by statute as stated in Skilling v. United States, __ U.S. __, 130 S. Ct. 2896, 2907,

177 L. Ed. 2d 619 (2010) (holding 1341 does not sanction the use of the intangible rights theory for

mail fraud convictions).

In response to the Supreme Courts decision in McNally, Congress added a definition of scheme or

artifice to defraud in 1988, providing that such term includes a scheme or artifice to deprive another of

the intangible right of honest services. 18 U.S.C.A. 1346; see McNally v. U.S., 483 U.S. 350, 107 S. Ct.

2875, 97 L. Ed. 2d 292, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6663 (1987) superseded by statute as stated in

Skilling v. United States, __ U.S. __, 130 S. Ct. 2896, 2907, 177 L. Ed. 2d 619 (2010).

18 U.S.C.A. 1341.

18 U.S.C.A. 1343.

See U.S. v. Coates, 949 F.2d 104, 106 (4th Cir. 1991).

Cleveland v. U.S., 531 U.S. 12, 20, 121 S. Ct. 365, 148 L. Ed. 2d 221, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P

9970 (2000).

Cleveland v. U.S., 531 U.S. 12, 1824, 121 S. Ct. 365, 148 L. Ed. 2d 221, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide

(CCH) P 9970 (2000).

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:1. Federal mail and wire fraud statutes, 1 White Collar Crime 8:1 (2d ed.)

10

Cleveland v. U.S., 531 U.S. 12, 27, 121 S. Ct. 365, 148 L. Ed. 2d 221, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P

9970 (2000).

End of Document

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S.

Government Works.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:2. Elements of mail and wire fraud, 1 White Collar Crime 8:2 (2d ed.)

1 White Collar Crime 8:2 (2d ed.)

White Collar Crime

Database updated June 2011

Joel Androphy

Chapter 8. Substantive Law: Mail Fraud, Wire Fraud

I. Fraud Statutes

References

8:2. Elements of mail and wire fraud

Wests Key Number Digest

Wests Key Number Digest, Postal Service

35(2)

Wests Key Number Digest, Telecommunications

1014(2)

Treatises and Practice Aids

Villa, Banking Crimes 7:4 to 7:15

Law Reviews and Other Periodicals

Clark, Ninth Circuit: Wire Fraud Conviction Need Not Include Showing of Conduct Violating Other

Statute or Regulation, 17 No. 7 Bus. Crimes Bull. 5 (March, 2010)

Additional References

Corporate Counsels Guide to White-Collar Crime 2:3

The elements of mail and wire fraud are identical.1 They are: (1) devising or intending to devise a scheme or

artifice to defraud another by means of a material misrepresentation, with (2) the intent to defraud through (3) the

use of mail or interstate wires.2

Westlaw. 2011 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. U.S. Govt. Works.

Footnotes

1

18 U.S.C.A. 1341.

See also 18 U.S.C.A. 1343; U.S. v. Pasquantino, 305 F.3d 291 (4th Cir. 2002), on rehg en banc, 336

F.3d 321 (4th Cir. 2003), judgment affd, 544 U.S. 349, 125 S. Ct. 1766, 161 L. Ed. 2d 619, 96 A.F.T.R.2d

2005-5392, 4 A.L.R. Fed. 2d 747 (2005) ( 1343 is not applicable to schemes to defraud foreign

governments of their revenues).

Carpenter v. U.S., 484 U.S. 19, 24, 108 S. Ct. 316, 98 L. Ed. 2d 275, 14 Media L. Rep. (BNA) 1853, 5

U.S.P.Q.2d 1059, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 93423, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide (CCH) P 6785 (1987).

See also U.S. v. Jackson, 346 F.3d 22 (2d Cir. 2003), adhered to on rehg, 362 F.3d 160 (2d Cir. 2004),

cert. granted, judgment vacated on other grounds, 543 U.S. 1097, 125 S. Ct. 1109, 160 L. Ed. 2d 988

(2005) (affirming wire fraud conviction based on defendants fraudulent use of victims credit card

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:2. Elements of mail and wire fraud, 1 White Collar Crime 8:2 (2d ed.)

information).

2

Neder v. U.S., 527 U.S. 1, 119 S. Ct. 1827, 144 L. Ed. 2d 35, 99-1 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P 50586, 83

A.F.T.R.2d 99-2668 (1999) (holding that while materiality of falsehood is an element of the federal mail

fraud, wire fraud, and bank fraud statutes, the harmless error rule can salvage a conviction without proof of

materiality); U.S. v. Fernandez, 282 F.3d 500 (7th Cir. 2002) (holding that although indictment failed to

expressly allege materiality element of mail fraud offense, allegations as a whole encompassed concept of

materiality; therefore, indictment was not defective).

End of Document

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S.

Government Works.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:3. Elements of mail and wire fraudIntent to defraud, 1 White Collar Crime 8:3...

1 White Collar Crime 8:3 (2d ed.)

White Collar Crime

Database updated June 2011

Joel Androphy

Chapter 8. Substantive Law: Mail Fraud, Wire Fraud

I. Fraud Statutes

References

8:3. Elements of mail and wire fraudIntent to defraud

Wests Key Number Digest

Wests Key Number Digest, Postal Service

35(5)

Wests Key Number Digest, Telecommunications

1014(3)

Treatises and Practice Aids

Villa, Banking Crimes 7:4 to 7:6

Forms

Am. Jur. Pleading and Practice Forms Annotated, Telecommunications 149.16

Additional References

Corporate Counsels Guide to White-Collar Crime 2:9

Proof of a specific intent to defraud is required under both the mail and wire fraud statutes.1 It is hornbook law

that a good faith belief by the defendant that his representation or promises are true necessarily negates fraudulent

intent and is, therefore, a defense to mail fraud.2

Note, however, than an expert witness may not testify that the defendant had the intent or state of mind necessary

to commit the crime because the defendants intent is an ultimate fact issue that must be decided by the jury.3

However, an expert may testify as to whether the defendant engaged in a scheme. For example, in United States v.

Winkle, the Sixth Circuit held that an experts testimony that the defendant carried out a check-kiting scheme was

properly admitted over the defendants objection.4 The court stated that the testimony helped the jury understand

a complex check-kiting scheme, and because the expert did not take a position on the defendants intent, the

testimony was properly admitted.5

In United States v. Keller,6 the Fifth Circuit held that the requisite intent to defraud exists if the defendant acts

knowingly and with the specific intent to deceive, ordinarily for the purpose of causing some financial loss to

another or bringing about some financial gain to himself.7

Similarly, in United States v. Czubinski,8 the First Circuit held that the government failed to prove that an IRS

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:3. Elements of mail and wire fraudIntent to defraud, 1 White Collar Crime 8:3...

agent committed wire fraud by accessing confidential information. In so holding, the court reasoned that on order

to establish the intent requirement, either some articulable harm must befall the holder of the information as a

result of the defendants activities, or some use must be intended by the person accessing the information, whether

or not this use is profitable in the economic sense.9

If the alleged victim receives what he bargains for, establishing intent to defraud may be problematic. In United

States v. Novak, the Second Circuit held that a lead union operator who demanded kickbacks from union

members in order to submit their timesheets could not be convicted of mail fraud because the union members

received exactly what they bargained for, which was not enough to satisfy the intent to defraud element in the

mail fraud statute.10

It is important to note, however, that it is not necessary to prove that the victim was actually defrauded, so long as

the defendant intended him to be defrauded and the scheme had the potential to defraud an ordinary person.11

Westlaw. 2011 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. U.S. Govt. Works.

Footnotes

1

Specific intent to defraud, however, need not be charged in the indictment. U.S. v. Brown, 459 F.3d 509,

519 (5th Cir. 2006); U.S. v. Brown, 147 F.3d 477, 483, 50 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 165, 1998 FED App. 0179P

(6th Cir. 1998); U.S. v. Cosentino, 869 F.2d 301, 30708 (7th Cir. 1989).

2

Durland v. U S, 161 U.S. 306, 31314, 16 S. Ct. 508, 40 L. Ed. 709 (1896); U.S. v. Rabinowitz, 327 F.2d

62, 7677 (6th Cir. 1964).

U.S. v. Winkle, 477 F.3d 407, 416, 72 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 592, 2007 FED App. 0070P (6th Cir. 2007).

U.S. v. Winkle, 477 F.3d 407, 416, 72 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 592, 2007 FED App. 0070P (6th Cir. 2007).

U.S. v. Winkle, 477 F.3d 407, 416, 72 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 592, 2007 FED App. 0070P (6th Cir. 2007).

U.S. v. Keller, 14 F.3d 1051, 1056 (5th Cir. 1994).

U.S. v. Keller, 14 F.3d 1051, 1056 (5th Cir. 1994). See U.S. v. Gray, 367 F.3d 1263, 1268 (11th Cir. 2004)

(stating that the mail fraud statute requires proof that the defendants scheme to defraud involved the use of

material, false representations or promises).

U.S. v. Czubinski, 106 F.3d 1069, 107475, 97-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P 50622, 79 A.F.T.R.2d 97-1664

(1st Cir. 1997).

U.S. v. Czubinski, 106 F.3d 1069, 107475, 97-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P 50622, 79 A.F.T.R.2d 97-1664

(1st Cir. 1997).

10

U.S. v. Novak, 443 F.3d 150, 159, 152 Lab. Cas. (CCH) P 10640 (2d Cir. 2006), subsequent determination,

188 Fed. Appx. 9 (2d Cir. 2006).

11

U.S. v. Schaffer, 599 F.2d 678, 67980 (5th Cir. 1979); U.S. v. Stouffer, 986 F.2d 916, 922 (5th Cir. 1993).

End of Document

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S.

Government Works.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:3. Elements of mail and wire fraudIntent to defraud, 1 White Collar Crime 8:3...

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:4. Elements of mail and wire fraudScheme or..., 1 White Collar Crime...

1 White Collar Crime 8:4 (2d ed.)

White Collar Crime

Database updated June 2011

Joel Androphy

Chapter 8. Substantive Law: Mail Fraud, Wire Fraud

I. Fraud Statutes

References

8:4. Elements of mail and wire fraudScheme or artifice to defraud

Wests Key Number Digest

Wests Key Number Digest, Postal Service

35(6)

Wests Key Number Digest, Telecommunications

1014(4)

A.L.R. Library

What Constitutes Causing Mail to Be Delivered for Purpose of Executing Scheme Prohibited by Mail

Fraud Statute (18 U.S.C.A. 1341), 9 A.L.R. Fed. 893

Treatises and Practice Aids

Villa, Banking Crimes 7:7 to 7:15

Because the courts have not established a clear definition of what actually constitutes a scheme or artifice to

defraud, the issue has been the subject of a great deal of litigation.1 A scheme to defraud does not have to be

fraudulent on its face; rather, it just must be reasonably calculated to deceive.2 The fact that a particular scheme is

impracticable or ultimately unsuccessful is not necessarily inconsistent with it being a fraudulent scheme.3

Rather, the essence of fraud is that the victim is persuaded to believe that which is not so.4

In Pasquantino v. United States, the Supreme Court held that a scheme to defraud a foreign government of tax

revenue violates the federal wire fraud statute.5 The defendants were convicted of smuggling discounted alcohol

from the United States into Canada without paying Canadian excise taxes.6 The Court concluded that the

uncollected tax revenue qualified as property because it constituted a valuable entitlement.7 The Court also

held that the defendants schemed to defraud the Canadian government within the meaning of the statute because

they concealed and failed to disclose the imported liquor to the Canadian authorities and on customs forms.8

The Court rejected the defendants argument that the convictions were barred by the common law revenue rule,

which prohibits courts from enforcing tax obligations of foreign countries.9 In rejecting this argument, the Court

concluded that the defendants convictions were permitted under the wire fraud statute because they did not

represent an attempt by the government to collect a foreign tax liability; rather, the Government was doing

nothing more than prosecuting domestic criminal conduct.10

At the core of the judicially defined scheme to defraud is the notion of a fiduciary trust owed to another and a

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:4. Elements of mail and wire fraudScheme or..., 1 White Collar Crime...

subsequent breach of that trust.11 Jurisdictions, however, differ in their analysis of whether the violation of a

fiduciary duty constitutes a violation of the mail or wire fraud statutes.

For example, in United States v. Little,12 the Fifth Circuit held that a kickback scheme violated a fiduciary

trust, even though no actual monetary loss was involved. The court found that the defendants willingness to sell

his product for the state-set priceless the kickback amountconstituted a property loss and therefore a

violation of a fiduciary trust and the mail fraud statute. Other courts, however, have determined that violations

of fiduciary duties were insufficient to trigger liability under the fraud statutes.13

Westlaw. 2011 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. U.S. Govt. Works.

Footnotes

1

See U.S. v. Leahy, 464 F.3d 773, 790, 71 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 479 (7th Cir. 2006) (scheme to defraud

existed where a private contractor misrepresented itself as a minority-owned or woman-owned business in

order to obtain a government despite the fact that the city suffered no monetary loss or pecuniary harm

because the contract was fully performed at the agreed price).

But see U.S. v. Lake, 472 F.3d 1247, 1255 (10th Cir. 2007) (holding mandatory reports filed with the SEC

were not transmitted as part of any unlawful scheme because the government failed to show that there was

anything misleading in the reports and their submission was required by law). See also U.S. v. Green, 592

F.3d 1057, 1064, 252 Ed. Law Rep. 608 (9th Cir. 2010) (holding that, to prove a scheme to defraud, the

government is not required to prove that the defendants conduct was otherwise illegal; therefore, the

government is not required to prove that the defendants conduct violated a specific statute or regulation).

2

U.S. v. Bruce, 488 F.2d 1224, 1229, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) P 94335 (5th Cir. 1973).

U.S. v. Church, 888 F.2d 20, 24 (5th Cir. 1989).

U.S. v. Church, 888 F.2d 20, 24 (5th Cir. 1989). For a discussion of unreasonable reliance on the part of

the victim, see Section 8.7 infra.

Pasquantino v. U.S., 544 U.S. 349, 125 S. Ct. 1766, 1771, 161 L. Ed. 2d 619, 96 A.F.T.R.2d 2005-5392, 4

A.L.R. Fed. 2d 747 (2005). For further discussion of this case, see G.J. Terwilliger III, United States v.

Pasquantino, NATL L.J., Nov. 7, 2005, at 16.

Pasquantino v. U.S., 544 U.S. 349, 125 S. Ct. 1766, 1770, 161 L. Ed. 2d 619, 96 A.F.T.R.2d 2005-5392, 4

A.L.R. Fed. 2d 747 (2005).

Pasquantino v. U.S., 544 U.S. 349, 125 S. Ct. 1766, 177172, 161 L. Ed. 2d 619, 96 A.F.T.R.2d

2005-5392, 4 A.L.R. Fed. 2d 747 (2005). See also U.S. v. Ali, 620 F.3d 1062, 106768 (9th Cir. 2010)

(holding that potential profits constitute money or property).

Pasquantino v. U.S., 544 U.S. 349, 125 S. Ct. 1766, 1773, 161 L. Ed. 2d 619, 96 A.F.T.R.2d 2005-5392, 4

A.L.R. Fed. 2d 747 (2005).

Pasquantino v. U.S., 544 U.S. 349, 125 S. Ct. 1766, 177374, 161 L. Ed. 2d 619, 96 A.F.T.R.2d

2005-5392, 4 A.L.R. Fed. 2d 747 (2005).

10

Pasquantino v. U.S., 544 U.S. 349, 125 S. Ct. 1766, 178687, 161 L. Ed. 2d 619, 96 A.F.T.R.2d

2005-5392, 4 A.L.R. Fed. 2d 747 (2005).

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:4. Elements of mail and wire fraudScheme or..., 1 White Collar Crime...

11

U.S. v. Capozzi, 883 F.2d 608, 616, 28 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 898 (8th Cir. 1989); U.S. v. Martin, 195 F.3d

961 (7th Cir. 1999) (recognizing that the fraud element of mail fraud may be predicated on breaches of

fiduciary duties created by federal law, and is not limited to breaches of state-law fiduciary duties). But see

U.S. v. Sancho, 957 F. Supp. 39, 4243 (S.D. N.Y. 1997), affd, 157 F.3d 918 (2d Cir. 1998) (overruled on

other grounds by, U.S. v. Rybicki, 354 F.3d 124 (2d Cir. 2003)) (holding that the plain language of 1343

and 1346 does not limit culpability to cases involving fiduciaries).

12

U.S. v. Little, 889 F.2d 1367, 1368 (5th Cir. 1989).

13

U.S. v. Ochs, 842 F.2d 515, 25 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 238 (1st Cir. 1988) (holding that a breach of fiduciary

duty is not sufficient property deprivation to constitute mail fraud); U.S. v. Zauber, 857 F.2d 137 (3d Cir.

1988) (rejecting constructive trust as basis for mail fraud conviction); U.S. v. Slay, 858 F.2d 1310 (8th Cir.

1988) (stating that withholding information from a governmental entity is insufficient to uphold a mail

fraud conviction); U.S. v. Lance, 848 F.2d 1497 (10th Cir. 1988) (paying kickbacks does not violate the

property requirement); U.S. v. Conover, 845 F.2d 266 (11th Cir. 1988) (breach of fiduciary duty does not

violate the mail fraud statute).

But see U.S. v. Hedaithy, 392 F.3d 580, 595 (3d Cir. 2004) (holding that a scheme in which imposters took

standardized tests and sent results to schools purportedly as defendants own scores deprived the

educational testing company of two property interests: confidential business information and tangible score

reports).

End of Document

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S.

Government Works.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:5. Elements of mail and wire fraudUse of mail or..., 1 White Collar Crime...

1 White Collar Crime 8:5 (2d ed.)

White Collar Crime

Database updated June 2011

Joel Androphy

Chapter 8. Substantive Law: Mail Fraud, Wire Fraud

I. Fraud Statutes

References

8:5. Elements of mail and wire fraudUse of mail or wires to execute scheme to defraud

Wests Key Number Digest

Wests Key Number Digest, Postal Service

35(10)

Wests Key Number Digest, Telecommunications

1014(5)

A.L.R. Library

Federal Criminal Prosecutions Under Wire Fraud Statute (18 U.S.C.A. 1343) for Use of Blue Box or

Similar Device Permitting User to Make Long-Distance Telephone Calls Not Reflected on Companys

Billing Records, 34 A.L.R. Fed. 278

Law Reviews and Other Periodicals

Clark, Fax Sent by Victim Sufficient to Establish Wire Fraud, 17 No. 7 Bus. Crimes Bull. 5 (March, 2010)

Additional References

Corporate Counsels Guide to White-Collar Crime 2:4 to 2:7

In a wire fraud case, the government must prove the use of interstate wire communications in furtherance of the

scheme to defraud.1 It is not necessary, however, to prove that the defendant himself personally performed the

fraudulent wire transfer in order to satisfy the element of causing a wire transmission in furtherance of the

fraudulent scheme.2 Rather, this element can be satisfied by showing that the defendant acted with knowledge

that a wire transfer would follow in the ordinary course of business or that such use could reasonable be

foreseen.3

For example, in United States v. Turner, the defendant, Cecil Turner, conspired with three janitors to defraud the

state by collecting inflated salaries based on falsified attendance logs.3.10 Turner argued that the direct deposit of

his inflated paychecks did not constitute a use of interstate wires because the use of such wires was a regular

part of his employment, and therefore not in furtherance of a fraudulent scheme.3.20

The court, however, concluded that routine or innocent wire transfers can form the basis of a wire fraud

conviction if they are part of the execution of the scheme.3.30 Because the money or property connected to the

janitors schemeunearned salarieswere received via wire transmission by way of fraud, the court held that the

defendant used interstate wires.3.40

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:5. Elements of mail and wire fraudUse of mail or..., 1 White Collar Crime...

The Second Circuit has held that the wire fraud statute applies to foreign communications made in the furtherance

of a scheme to defraud. The court reasoned that Congress specifically amended the statute in 1956 to insert the

words foreign commerce in reaction to a failed prosecution of a defendant who made calls from Mexico to the

United States in furtherance of a scheme to defraud and who was able to successfully argue that the statute did not

apply to foreign communications.4 In so holding, the court stated:

There would seem to be no logical reason for holding that Congress intended to punish those who

cause the violation of a law regulating and protecting foreign commerce only when they act within

the borders of the United States or that Congress is powerless to protect foreign commerce and those

who engage in foreign commerce from intentionally injurious acts, simply because those acts occur

outside our borders. We therefore believe that Congress clearly intended conduct such as [foreign

communications] to be within the reach of our criminal laws.5

In a mail fraud case, the government must prove that the United States mails were used to further the fraudulent

scheme.6 Because the jurisdictional basis of the mail fraud statute derives from the Postal Power, it is not

necessary for the prosecution to prove the existence of an interstate mailing.7 The mail fraud statute covers all

items passing through the United States mails, even if intrastate.8 However, the connection between the alleged

fraud and the use of the mails must be real and proximate, not merely abstract or remote, in order for a conviction

for mail fraud to stand.9

Although the government is required to show that particular documents were sent through the United States mails

and not by hand delivery by the bidder or its agent, or delivered via messenger or courier, the government does

not need to show that any of the defendants themselves mailed anything.10 Rather, the government must show

only that the defendants caused mailings in furtherance of the scheme to defraud.11

The in furtherance requirement under the mail fraud statute is satisfied by proving that the defendant acted

with knowledge that the use of the mails will follow in the ordinary course of business, or where he could

reasonably foresee that the use of the mail would result. It is not necessary to prove the accused actually

intended the mail to be used.12

While the general rule is that mailings subsequent to the fruition of the scheme do not trigger liability under the

mail fraud statute because they do not fulfill the in furtherance requirement, there are exceptions to this rule.

For example, if the mails are used as a means of concealment so that further frauds that are part of the scheme

may be perpetrated, then such mailings satisfy the in furtherance requirement.13 This kind of mailing is called a

lulling letter because it is designed to lull the victims into a false sense of security, postpone their ultimate

complaint to the authorities, and therefore make the apprehension of the defendant less likely than if no mailings

had taken place.14

In light of the Supreme Courts decision in Schmuck v. United States, the relationship between the mailing and

the scheme must undergo a subjective examination to address whether the mailing is part of the execution of the

scheme as conceived by the perpetrator at the time [of the mailing], regardless of whether the mailing later,

through hindsight, may prove to have been counterproductive and return to haunt the perpetrator of the fraud.15

Essentially, this case has greatly broadened the reach of the mail fraud statute in that innocent mailings can supply

the use of the mail element for mail fraud.16

The accused, Wayne T. Schmuck, was a used car wholesaler in Wisconsin who, after purchasing a used car,

would roll back odometers and resell to unwitting retailers.17 Because of their supposedly low mileage, the prices

of these cars were fraudulently inflated. This fraudulent price inflation was passed on to consumers who had no

idea that their cars had been driven many more miles than their odometers indicated. Importantly, to complete the

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:5. Elements of mail and wire fraudUse of mail or..., 1 White Collar Crime...

resale, the retailer had to submit title applications to the Wisconsin Department of Transportation on behalf of his

customers; this step of the process supplied the use of the mail requirement for each of the mail fraud counts

against Schmuck.18

In affirming his conviction, the Court reasoned that although Schmuck himself never mailed anything in

furtherance of his scheme and the registration forms that were mailed did not directly contribute to the duping of

either the retailers or the individual customers, these mailings were necessary to the passage of title, which in

turn was essential to the perpetuation of Schmucks scheme.19 As the Supreme Court noted, a rational jury

could have concluded that the success of Schmucks venture depended upon his continued harmonious relations

with, and good reputation among, retail dealers, which in turn required the smooth flow of cars from the dealers to

their Wisconsin customers.20

In a strongly worded dissent, Justice Scalia condemned the majority opinion for not following precedent with

respect to the scope of the in furtherance requirement. Scalia asserted that the statute does not reach every

fraudulent scheme, but rather only those in which the use of mails is a part of the execution of the fraud.21 In

other words, he wrote, it is mail fraud, not mail and fraud, that incurs liability.22

Scalia asserted that both United States v. Maze23 and Kann v. United States24 hold that, in cases where the

scheme has reached its fruition, subsequent mailings immaterial to the scheme do not trigger the statute. Scalia

then argued that these two cases were on point because Schmucks scheme had reached its fruition when he sold

the cars to the wholesalers; the subsequent mailings were immaterial to Schmuck since he had already received

his money.25

The Schmuck ruling seems to indicate that a mailing which furthers the scheme, whether that mailing aids or

actually hinders the scheme, will trigger the mail fraud statute; in other words, the mailing need only be related to

the scheme. As the Court concluded in Schmuck, [t]he mail fraud statute includes no guarantee that the use of the

mails for the purpose of executing a fraudulent scheme will be risk free. Those who use the mails to defraud

proceed at their peril.26

Westlaw. 2011 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. U.S. Govt. Works.

Footnotes

1

U.S. v. Prince, 214 F.3d 740, 748, 2000 FED App. 0186P (6th Cir. 2000).

2

U.S. v. Adcock, 534 F.3d 635, 640 (7th Cir. 2008). U.S. v. Griffith, 17 F.3d 865, 40 Fed. R. Evid. Serv.

565, 1994 FED App. 0067P (6th Cir. 1994) (citing U.S. v. Campbell, 845 F.2d 1374, 25 Fed. R. Evid.

Serv. 960 (6th Cir. 1988)).

U.S. v. Adcock, 534 F.3d 635, 640 (7th Cir. 2008).

3.10 U.S. v. Turner, 551 F.3d 657, 660 (7th Cir. 2008), cert. denied, 129 S. Ct. 2748, 174 L. Ed. 2d 249 (2009).

3.20 U.S. v. Turner, 551 F.3d 657, 667 (7th Cir. 2008), cert. denied, 129 S. Ct. 2748, 174 L. Ed. 2d 249 (2009).

3.30 U.S. v. Turner, 551 F.3d 657, 668 (7th Cir. 2008), cert. denied, 129 S. Ct. 2748, 174 L. Ed. 2d 249 (2009).

3.40 U.S. v. Turner, 551 F.3d 657, 668 (7th Cir. 2008), cert. denied, 129 S. Ct. 2748, 174 L. Ed. 2d 249 (2009).

4

U.S. v. Kim, 246 F.3d 186, 189 (2d Cir. 2001) (citing U.S. v. Braverman, 376 F.2d 249, 251 (2d Cir.

1967)); but see U.S. v. Radziszewski, 474 F.3d 480, 485 (7th Cir. 2007), as amended on denial of rehg,

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:5. Elements of mail and wire fraudUse of mail or..., 1 White Collar Crime...

(May 14, 2007) (defendants intention to repay fraudulently obtained funds does not support a good faith

defense to mail and wire fraud because the crime of fraud is complete when the funds are obtained under

false pretenses).

5

U.S. v. Kim, 246 F.3d 186, 189 (2d Cir. 2001) (citing U.S. v. Braverman, 376 F.2d 249, 251 (2d Cir.

1967)).

See U.S. v. Hatch, 926 F.2d 387, 392, 32 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 556 (5th Cir. 1991). Note that the government

may be able to prove use of the mails circumstantially, or through a witness who testifies that a specific

item would have been mailed as a matter of routine or custom. U.S. v. Scott, 668 F.2d 384, 388, 9 Fed. R.

Evid. Serv. 899 (8th Cir. 1981); but see U.S. v. Massey, 827 F.2d 995, 999 (5th Cir. 1987) (use of

circumstantial evidence to prove a mailing does not relieve the government of its burden of establishing the

elements of the offense charged beyond a mere likelihood or probability or by more than mere

speculation); U.S. v. United Skates of America, Inc., 727 F. Supp. 430, 431 (N.D. Ill. 1989) ([W]hile

circumstantial evidence and the inferences drawn therefrom may certainly be sufficient to support a finding

on a particular element of an offense, mere suspicion or speculation cannot be the basis for the creation of

logical inferences.).

U.S. v. Elliott, 89 F.3d 1360, 1364 (8th Cir. 1996).

U.S. v. Elliott, 89 F.3d 1360, 1364 (8th Cir. 1996).

See U.S. v. Hopkins, 357 F.2d 14, 16 (6th Cir. 1966).

10

U.S. v. Tencer, 107 F.3d 1120, 1125 (5th Cir. 1997).

11

U.S. v. Tencer, 107 F.3d 1120, 1125 (5th Cir. 1997).

12

U.S. v. Fermin Castillo, 829 F.2d 1194, 1198 (1st Cir. 1987). But see U.S. v. Smith, 934 F.2d 270 (11th

Cir. 1991) (rejected by, U.S. v. Pimental, 380 F.3d 575 (1st Cir. 2004)) (holding that defendant cannot be

convicted of mail fraud based on mailing between insurance companys offices to approve his payment

draft because it was not reasonably foreseeable to defendant that company would mail draft.). Examples of

mailings which are not in furtherance of a scheme are routine mailings made without the presence of a

fraudulent scheme, and mailings which occur after the completion of the scheme. See Parr v. U.S., 363

U.S. 370, 80 S. Ct. 1171, 4 L. Ed. 2d 1277 (1960); U.S. v. Maze, 414 U.S. 395, 94 S. Ct. 645, 38 L. Ed. 2d

603 (1974).

13

Kann v. U.S., 323 U.S. 88, 9495, 65 S. Ct. 148, 89 L. Ed. 88, 157 A.L.R. 406 (1944).

14

U.S. v. Maze, 414 U.S. 395, 403, 94 S. Ct. 645, 38 L. Ed. 2d 603 (1974). See also, U.S. v. Evans, 473 F.3d

1115, 1123 (11th Cir. 2006) (holding that a fax transmission from the victim to the defendant confirming a

meeting to discuss the status of the victims account fell within the lulling doctrine because it was part and

parcel of the scheme to delay detection of the fraud by lulling [the victim] into believing that the parties

difficulties would be worked out).

15

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 715, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989).

16

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989); see U.S. v. Arledge, 553 F.3d

881 (5th Cir. 2008), cert. denied, 129 S. Ct. 2028, 173 L. Ed. 2d 1088 (2009) (holding that the mailing of

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:5. Elements of mail and wire fraudUse of mail or..., 1 White Collar Crime...

legitimate claims to recover from a class action settlement fund satisfied the use of mails requirement

because those claims served to facilitate the submission of other fraudulent claims).

17

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 707, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989).

18

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 707, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989).

19

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 712, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989).

20

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 71112, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989).

21

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 723, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989) (citing Kann v. U.S., 323

U.S. 88, 95, 65 S. Ct. 148, 89 L. Ed. 88, 157 A.L.R. 406 (1944).

22

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 723, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989).

23

U.S. v. Maze, 414 U.S. 395, 94 S. Ct. 645, 38 L. Ed. 2d 603 (1974).

24

Kann v. U.S., 323 U.S. 88, 95, 65 S. Ct. 148, 89 L. Ed. 88, 157 A.L.R. 406 (1944).

25

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 723, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989). See also U.S. v. Evans,

148 F.3d 477 (5th Cir. 1998).

26

Schmuck v. U.S., 489 U.S. 705, 715, 109 S. Ct. 1443, 103 L. Ed. 2d 734 (1989).

End of Document

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S.

Government Works.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:6. Elements of mail and wire fraudMateriality, 1 White Collar Crime 8:6 (2d ed.)

1 White Collar Crime 8:6 (2d ed.)

White Collar Crime

Database updated June 2011

Joel Androphy

Chapter 8. Substantive Law: Mail Fraud, Wire Fraud

I. Fraud Statutes

References

8:6. Elements of mail and wire fraudMateriality

Wests Key Number Digest

Wests Key Number Digest, Postal Service

35(2)

Wests Key Number Digest, Telecommunications

1014(2)

Additional References

Corporate Counsels Guide to White-Collar Crime 2:8

In order for your client to be convicted of mail or wire fraud, the government must prove that your client made a

material misrepresentation or omission and had the intent to deprive his customers of property (money) or honest

services.1

Case law provides several bases to attack the conclusion that the statements (or omissions) made in

communications rise to the level of being criminally material or reflect the requisite intent, and thus are fraudulent

within the meaning of the mail and wire fraud statutes.

In Neder v. United States, the United States Supreme Court held that materiality of falsehood is an element of

mail and wire fraud.2 The Court cited the definition found in the Second Restatement of Torts, which states that a

matter is material if:

(a) a reasonable man would attach importance to its existence or nonexistence in determining his

choice of action in the transaction in question; or

(b) the maker of the representation knows or has reason to know that its recipient regards or is likely

to regard the matter as important in determining his choice of action, although a reasonable man

would not so regard it.3 In 2003, a circuit court articulated the Neder requirement as follows: [I]t is

clear that as an element of the scheme to defraud requirement, the government must prove that the

defendant said something materially false.4

In United States v. DeSantis, the court affirmed a mail fraud conviction despite the defendants challenge to the

materiality of his statements.5 Without discussion, the court concluded that reasonable minds could differ whether

the defendants statementsthat his commissions were only 10% when they were actually 20%were material.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:6. Elements of mail and wire fraudMateriality, 1 White Collar Crime 8:6 (2d ed.)

Materiality, the court explained, is a fact question for the jury.6

In United States v. Daniel, the court concluded that a reasonable jury could find that the defendants

misrepresentations were material when the defendant lied to his company to obtain loans for personal reasons by

stating that the loans were for company investment purposes.7 The court reasoned that the false statements were

arguably material because the defendant knew the statements were false, and the statements would have affected a

reasonable persons actions in the situation.8

Daniel serves as an interesting example of how courts may frame the issue of intent under the mail and wire fraud

statutes by blending intent with the concept of materiality. To convict a defendant of wire fraud the government

must prove specific intent, which means not only that a defendant must knowingly make a material

misrepresentation or knowingly omit a material fact, but also that the misrepresentation or omission must have the

purpose of inducing the victim of the fraud to part with property or undertake some action that he would not

otherwise do absent the misrepresentation or omission.9

In its analysis following this rule, the court framed the issue as follows: The question here is whether Daniel

made his representations intending to get Century to loan him money that it would not have otherwise loaned

him.10 The answer was yes.11

The question of materiality (or intent) comes down to two alternative burdens. Under the first alternative, the

purpose of the statement or omission must be to induce the victim of the fraud to part with property. Under the

second alternative, the question is whether the misrepresentation or omission would influence someone to

undertake some action that he would not otherwise do if it were not for the misrepresentation or omission.12

The second alternative would probably be an easier burden to meet. At first blush, it has a certain but for logic

to it. But for the omission or misrepresentation, the buyer would not have made a purchase; thus, it is material.

There is an enormous risk, however, in applying such logic to arms length sales transactions because anything

said or not said becomes material; it risks materializing everything about a sales transaction.

Any consumer would like to know more about the kind of deal he is getting, so just about anything is going to

seem material to the consumer when money is changing hands. To combat such a result, many circuits have

tempered the reach on arms length transactions by focusing on intent to defraud or requiring reasonable reliance

by the consumer, as discussed below.

Westlaw. 2011 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. U.S. Govt. Works.

Footnotes

1

Note that it is no defense that the defendant had an honest belief that the scheme would work. Such a belief

does not negate the falsity of misrepresentations or knowledge that statements were false when made. U.S.

v. Alexander, 743 F.2d 472, 478, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 70011 (7th Cir. 1984).

2

Neder v. U.S., 527 U.S. 1, 119 S. Ct. 1827, 1840, 144 L. Ed. 2d 35, 99-1 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) 50586, 83

A.F.T.R.2d 99-2668 (1999).

Neder v. U.S., 527 U.S. 1, 119 S. Ct. 1827, 1840, 144 L. Ed. 2d 35, 99-1 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) 50586, 83

A.F.T.R.2d 99-2668 (1999) (quoting Restatement (Second) of Torts 538 (1977)). U.S. v. Daniel, 329

F.3d 480, 486, 2003 FED App. 0153P (6th Cir. 2003) (material misrepresentations or omissions are those

that might affect a reasonable persons actions in a situation); U.S. v. Rybicki, 354 F.3d 124, 145 (2d Cir.

2003) (en banc) (holding that misrepresentation or omission at issue is material when that

misinformation or omission would naturally tend to lead or is capable of leading a reasonable employer to

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:6. Elements of mail and wire fraudMateriality, 1 White Collar Crime 8:6 (2d ed.)

change its conduct).

4

U.S. v. Daniel, 329 F.3d 480, 486, 2003 FED App. 0153P (6th Cir. 2003).

U.S. v. DeSantis, 134 F.3d 760, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) 90120, 48 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 807, 1998 FED

App. 0018P (6th Cir. 1998).

U.S. v. DeSantis, 134 F.3d 760, 764, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) 90120, 48 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 807, 1998

FED App. 0018P (6th Cir. 1998). See also U.S. v. Cornish, 68 Fed. Appx. 557, 559 (6th Cir. 2003) (stating

there was sufficient evidence that defendants deceit was material because defendant induced victim

company to actually purchase an account receivable from him based on his misrepresentations).

U.S. v. Daniel, 329 F.3d 480, 487, 2003 FED App. 0153P (6th Cir. 2003).

U.S. v. Daniel, 329 F.3d 480, 487, 2003 FED App. 0153P (6th Cir. 2003).

U.S. v. Daniel, 329 F.3d 480, 487, 2003 FED App. 0153P (6th Cir. 2003).

10

U.S. v. Daniel, 329 F.3d 480, 487, 2003 FED App. 0153P (6th Cir. 2003).

11

U.S. v. Daniel, 329 F.3d 480, 489, 2003 FED App. 0153P (6th Cir. 2003).

12

See U.S. v. Gray, 96 F.3d 769, 77576, 112 Ed. Law Rep. 637 (5th Cir. 1996).

End of Document

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S.

Government Works.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:7. Elements of mail and wire fraudUnreasonable reliance, 1 White Collar Crime ...

1 White Collar Crime 8:7 (2d ed.)

White Collar Crime

Database updated June 2011

Joel Androphy

Chapter 8. Substantive Law: Mail Fraud, Wire Fraud

I. Fraud Statutes

References

8:7. Elements of mail and wire fraudUnreasonable reliance

Wests Key Number Digest

Wests Key Number Digest, Postal Service

35(2)

Wests Key Number Digest, Telecommunications

1014(2)

Historically, [i]n order to establish a scheme to defraud, an essential element of mail fraud, there must be proof

of fraudulent misrepresentations or omissions reasonably calculated to deceive persons of ordinary prudence and

comprehension.1

In recent years, the requirement of showing that the scheme would deceive a person of ordinary prudence has

generally been superseded by a less strict standard.2 Some circuits, however, have adopted the rule in their

jurisdictional case law.3

The circuits that have the rule rarely exercise it in favor of a defendant. United States v. Brown is the only major

criminal case in which the court absolved the defendants by finding unreasonable reliance by the alleged victim of

fraud, and it has been subsequently overruled on point by the Eleventh Circuit.4 In Svete, the Eleventh Circuit

overruled Brown and held that the offense of mail fraud does not require proof of a scheme to deceive a person of

ordinary prudence.5

In overruling Brown, the Eleventh Circuit noted the overwhelming criticism of the Brown decision by both courts

and scholars alike.6 Specifically, the court noted that the decision had been disagreed with by every other court

that had addressed the issue, and that the decision was inconsistent with the plain language of the mail fraud

statute, which prohibits any scheme or artifice to defraud.7

The defense of unreasonable reliance was similarly rejected in United States v. Maxwell.8 In Maxwell, the

defendant challenged a wire fraud conviction on the grounds that no reasonable person would have believed her

misrepresentations. The court held that the issue of unreasonable belief by the victim is irrelevant; instead, the

only relevant issue is whether there is a plan, scheme, or artifice intended to defraud.9

The movement away from requiring reasonable reliance stems from the concern that such a requirement unfairly

penalizes victims while rewarding defendants for targeting nave individuals. As Judge Posner commented in

reaction to the Brown decision, it is hard to believe [that the holding in Brown] was intended to be understood

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:7. Elements of mail and wire fraudUnreasonable reliance, 1 White Collar Crime ...

literally, for if it were it would invite con men to prey on people of below-average judgment or intelligence, who

are anyway the biggest targets of such criminals and hence the people most needful of the laws protection.10

Additionally, as the Tenth Circuit noted in United States v. Drake, the focus of the fraud analysis is supposed to

be on the violatornot the victim.11

Westlaw. 2011 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. U.S. Govt. Works.

Footnotes

1

Blount Financial Services, Inc. v. Walter E. Heller and Co., 819 F.2d 151, 153, R.I.C.O. Bus. Disp. Guide

(CCH) 6633, 1987-1 Trade Cas. (CCH) 67580 (6th Cir. 1987) (citing U.S. v. Van Dyke, 605 F.2d 220,

225, 4 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1160 (6th Cir. 1979)).

2

See, e.g., U.S. v. Rosby, 454 F.3d 670, 674 (7th Cir. 2006); U.S. v. Ciccone, 219 F.3d 1078, 1083 (9th Cir.

2000) (rejecting defendants argument that the government had to prove the scheme was reasonably

calculated to deceive an ordinary, prudent person because it is immaterial whether only the most gullible

would have been deceived by the scheme);

U.S. v. Coffman, 94 F.3d 330, 334 (7th Cir. 1996) (rejecting the rule generally but reasoning that a

reasonable person analysis may be appropriate: (1) as circumstantial evidence of the issue of intent where

defendant claims he did not intend to deceive anyone and there is little available evidence as to intent; or

(2) in cases that involve the indistinct border between real fraud and sharp dealing, such as distinguishing

between the small lies of puffery and elaborate fraudulent schemes); U.S. v. Maxwell, 920 F.2d 1028, 1038

(D.C. Cir. 1990) (rejecting the rule); U.S. v. Brien, 617 F.2d 299, 311 (1st Cir. 1980) (rejecting the rule).

See, e.g., U.S. v. Goodman, 984 F.2d 235, 237 (8th Cir. 1993) (citing the rule); U.S. v. Bruce, 488 F.2d

1224, 1229, Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) 94335 (5th Cir. 1973) (citing the rule). But see U.S. v. Davis, 226

F.3d 346, 358359 (5th Cir. 2000) (concluding that the trial court did not err by giving jury instructions

stating that the navet of the victim did not excuse criminal liability because defendants argument that a

material misrepresentation is only material if a reasonable person would rely on it overlooked the two

alternative definitions for materiality in Neder v. U.S., 527 U.S. 1, 119 S. Ct. 1827, 144 L. Ed. 2d 35, 99-1

U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) 50586, 83 A.F.T.R.2d 99-2668 (1999), reasoning that one of them does not require

reasonable reliance if the maker knew or had reason to know his victim would rely). Cf. U.S. v. Boyd, 2

Fed. Appx. 86 (2d Cir. 2001) (collecting cases from the circuits that disavow the rule but not deciding the

issue); U.S. v. Falkowitz, 214 F. Supp. 2d 365, 376377 (S.D. N.Y. 2002) (discussing the applicability of

the rule in criminal fraud, arguing that it is a part of civil fraud but not all circuits have imported it into

their criminal law fraud and giving reasons why it should not be applied to criminal fraud).

The rule has only appeared once in an opinion in a criminal case in the Sixth Circuit. See U.S. v. Van

Dyke, 605 F.2d 220, 225, 4 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 1160 (6th Cir. 1979) (citing the rule and finding reasonable

reliance on false statements by jewelry franchise conman who advertised the start-up franchise program in

magazines). See also, U.S. v. Frost, 125 F.3d 346, 372, 1997 FED App. 0274P (6th Cir. 1997) (although

the rule is not discussed, the case illustrates a jury instruction that has the rule in it).

U.S. v. Brown, 79 F.3d 1550, 1558 (11th Cir. 1996) (overruled by, U.S. v. Svete, 556 F.3d 1157 (11th Cir.

2009)).

U.S. v. Svete, 556 F.3d 1157, 1160 (11th Cir. 2009) (en banc).

U.S. v. Svete, 556 F.3d 1157, 116768 (11th Cir. 2009) (en banc).

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8:7. Elements of mail and wire fraudUnreasonable reliance, 1 White Collar Crime ...

U.S. v. Svete, 556 F.3d 1157, 116768 (11th Cir. 2009) (en banc) (emphasis in original).

U.S. v. Maxwell, 920 F.2d 1028, 1036 (D.C. Cir. 1990).

See U.S. v. Taylor, 832 F.2d 1187, 1192 (10th Cir. 1987).

10

U.S. v. Svete, 556 F.3d 1157, 116768 (11th Cir. 2009) (en banc) (quoting U.S. v. Coffman, 94 F.3d 330,

334 (7th Cir. 1996) (Posner, J.)).

11

U.S. v. Drake, 932 F.2d 861, 86364, 33 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 64 (10th Cir. 1991).

End of Document

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S.

Government Works.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Robert Peterson v. Portfolio Recovery Associates, 3rd Cir. (2011)Dokument9 SeitenRobert Peterson v. Portfolio Recovery Associates, 3rd Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misprision of Felony 18 USC 4 - Title 18 Crimes and Criminal Procedure United States Code - United States Courts - Federal Law - Criminal Statutes - California Federal Criminal Law - US Attorney General - United States District Court - 9th Circuit Court of Appeals - US Attorney CaliforniaDokument1 SeiteMisprision of Felony 18 USC 4 - Title 18 Crimes and Criminal Procedure United States Code - United States Courts - Federal Law - Criminal Statutes - California Federal Criminal Law - US Attorney General - United States District Court - 9th Circuit Court of Appeals - US Attorney CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rosenthal FDCPADokument7 SeitenRosenthal FDCPAYared KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- US Internal Revenue Service: p15 - 1999Dokument64 SeitenUS Internal Revenue Service: p15 - 1999IRSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cover Letter and Brief To Court For Foreclosure Defense 8-16-11Dokument3 SeitenCover Letter and Brief To Court For Foreclosure Defense 8-16-11jack1929Noch keine Bewertungen

- City of Chicago Motion To Dismiss Red Light CaseDokument40 SeitenCity of Chicago Motion To Dismiss Red Light CasePatrick J Keating100% (1)

- HP Locate FDCPA LawsuitDokument15 SeitenHP Locate FDCPA LawsuitRick HartmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Dismissed For Lack of Capacity To Sue, in Pinella County, Fla, 01-15-2010Dokument3 SeitenCase Dismissed For Lack of Capacity To Sue, in Pinella County, Fla, 01-15-2010wicholacayo100% (2)

- Request For Dismissal - With PrejudiceDokument2 SeitenRequest For Dismissal - With PrejudiceZackery BisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freedom of Movement Under United States LawDokument8 SeitenFreedom of Movement Under United States LawcatalinatorreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To Stay LitigationDokument10 SeitenMotion To Stay LitigationpauloverhauserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint, Civil Rights, ADA 5:10-Cv-00503, All ExhibitsDokument479 SeitenComplaint, Civil Rights, ADA 5:10-Cv-00503, All ExhibitsNeil Gillespie100% (1)

- Dan Bui - Motion For Early Terminatino of ProbationDokument4 SeitenDan Bui - Motion For Early Terminatino of ProbationJennifer Le100% (1)

- Subpoena Ducas TecumDokument1 SeiteSubpoena Ducas TecumANGELONoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To Dismiss CH 13 Petition For Bad Faith: Benjamin Levi Jones-NormanDokument8 SeitenMotion To Dismiss CH 13 Petition For Bad Faith: Benjamin Levi Jones-Normangw9300100% (1)

- Order For Contempt Past Due Child SupportDokument1 SeiteOrder For Contempt Past Due Child SupportANGELONoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter To Governor COVID-19Dokument2 SeitenLetter To Governor COVID-19Ryan L Morrison Kboi100% (3)

- FOIL RequestDokument2 SeitenFOIL RequestSergio HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS APPEAL AND STAY BRIEFING SCHEDULEdd.242731.5.0Dokument12 SeitenUNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS APPEAL AND STAY BRIEFING SCHEDULEdd.242731.5.0D B Karron, PhDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drew v. Equifax, C07-00726 SI (N.D. Cal. Dec. 3, 2010)Dokument22 SeitenDrew v. Equifax, C07-00726 SI (N.D. Cal. Dec. 3, 2010)Venkat BalasubramaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- CrimInfo&PCAff-Peppers, Robin 18 F6 714Dokument5 SeitenCrimInfo&PCAff-Peppers, Robin 18 F6 714Anonymous anQ4GGvNoch keine Bewertungen

- Virginia Power Stop FC LawsDokument3 SeitenVirginia Power Stop FC LawsKNOWLEDGE SOURCENoch keine Bewertungen

- Southern Florida: United States Bankruptcy CourtDokument38 SeitenSouthern Florida: United States Bankruptcy CourtMy-Acts Of-SeditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biolsi V Jefferson Capital Systems LLC FDCPA Complaint Debt CollectionDokument8 SeitenBiolsi V Jefferson Capital Systems LLC FDCPA Complaint Debt CollectionghostgripNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hawaii Office of Information Practices Opinion No. 04-02 Re: Office of Disciplinary Counsel and Disciplinary BoardDokument20 SeitenHawaii Office of Information Practices Opinion No. 04-02 Re: Office of Disciplinary Counsel and Disciplinary BoardIan LindNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospital's Legal Opinion On Chapter 55ADokument8 SeitenHospital's Legal Opinion On Chapter 55AEmily Featherston GrayTvNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demurrer or Dismiss Debt Collector For Lack of Standing To Sue No Certificate of Authority Secretary of State Foreclosure Credit Cards PDFDokument15 SeitenDemurrer or Dismiss Debt Collector For Lack of Standing To Sue No Certificate of Authority Secretary of State Foreclosure Credit Cards PDFאלוהי לוֹחֶםNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steve Nash Child SupportDokument26 SeitenSteve Nash Child Supportray sternNoch keine Bewertungen

- IndyStar Cease & Desist LetterDokument2 SeitenIndyStar Cease & Desist LetterIndiana Public Media NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- City MotionDokument7 SeitenCity MotionJohn DodgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Records RequestDokument7 SeitenRecords RequestChristopher BakerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theft or Bribery Concerning Federal Funds: 18 USC 666 Federal Criminal Law United States Code Title 18 Crimes and Criminal Procedure - United States Attorney - United States District Court CaliforniaDokument4 SeitenTheft or Bribery Concerning Federal Funds: 18 USC 666 Federal Criminal Law United States Code Title 18 Crimes and Criminal Procedure - United States Attorney - United States District Court CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Cronshaw, Mark-Memorandum in Support of 12 (B) (6) Motion To DismissDokument17 SeitenCronshaw, Mark-Memorandum in Support of 12 (B) (6) Motion To DismissJ DoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawsuit Against Collier County Sheriff's OfficeDokument42 SeitenLawsuit Against Collier County Sheriff's OfficeDevan PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Garrett Daily: Motion To Dismiss Appeal - Disentitlement Doctrine - Dong v. Garbe Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Mary Anne Grilli - 6th District Court of Appeal San Jose - Administrative Presiding Judge Conrad L. Rushing - Trial Attorney Bradford BaughDokument57 SeitenGarrett Daily: Motion To Dismiss Appeal - Disentitlement Doctrine - Dong v. Garbe Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Mary Anne Grilli - 6th District Court of Appeal San Jose - Administrative Presiding Judge Conrad L. Rushing - Trial Attorney Bradford BaughCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- SEC v. Babikian Doc 40 Filed 23 May 14Dokument3 SeitenSEC v. Babikian Doc 40 Filed 23 May 14scion.scionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Govino LLC v. Whitepoles LLC - R&R On Default JudgmentDokument25 SeitenGovino LLC v. Whitepoles LLC - R&R On Default JudgmentSarah BursteinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fulton County Superior Court Class Action Lawsuit Challenges GDOL Unemployment Benefits DelaysDokument45 SeitenFulton County Superior Court Class Action Lawsuit Challenges GDOL Unemployment Benefits DelaysBarry BrownNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alabama Collection LawDokument6 SeitenAlabama Collection LawBradNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cushman v. Trans Union CorporationDokument11 SeitenCushman v. Trans Union CorporationKenneth SandersNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTSJP Complaint v2Dokument33 SeitenCTSJP Complaint v2Gabriel PiemonteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stroman ComplaintDokument79 SeitenStroman ComplaintFrank JeanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bankruptcy OrderDokument150 SeitenBankruptcy OrderdkbradleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CDC Eviction Moratorium Emergency Order Federal RegisterDokument6 SeitenCDC Eviction Moratorium Emergency Order Federal RegisterRichard VetsteinNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States District Court Southern District of Florida Case No. 10-60786-Civ-COOKE/BANDSTRADokument30 SeitenUnited States District Court Southern District of Florida Case No. 10-60786-Civ-COOKE/BANDSTRADavid Oscar MarkusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To CompelDokument27 SeitenMotion To CompelABC10Noch keine Bewertungen

- MTD Fraud On Court - JPMOrgan and ShapiroDokument6 SeitenMTD Fraud On Court - JPMOrgan and ShapiroMackLawfirmNoch keine Bewertungen

- 202PetitionRYC PDFDokument9 Seiten202PetitionRYC PDFRYCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Habeas Petition For Randall ScottiDokument12 SeitenHabeas Petition For Randall ScottiJOEMAFLAGENoch keine Bewertungen

- 42 Usc 1983 Wrongful Death AuthoritiesDokument33 Seiten42 Usc 1983 Wrongful Death Authoritiesdavidchey4617100% (1)

- Annotated Summary of Public Records History-1Dokument260 SeitenAnnotated Summary of Public Records History-1al_crespo_2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To Dismiss An Adversary Complaint For FraudDokument3 SeitenMotion To Dismiss An Adversary Complaint For FraudStan Burman100% (1)

- Circuit Court Foreclosure AnswerDokument6 SeitenCircuit Court Foreclosure AnswerMatthew Weidner100% (1)

- Defendant Response To Motion To RemandDokument18 SeitenDefendant Response To Motion To RemandDeborah ToomeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jones V Florida Recusal OpinionDokument25 SeitenJones V Florida Recusal OpinionLaw&CrimeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petition for Certiorari – Patent Case 01-438 - Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a)Von EverandPetition for Certiorari – Patent Case 01-438 - Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a)Noch keine Bewertungen

- You Are My Servant and I Have Chosen You: What It Means to Be Called, Chosen, Prepared and Ordained by God for MinistryVon EverandYou Are My Servant and I Have Chosen You: What It Means to Be Called, Chosen, Prepared and Ordained by God for MinistryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lighting the Way: Federal Courts, Civil Rights, and Public PolicyVon EverandLighting the Way: Federal Courts, Civil Rights, and Public PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Respondent's Statement of Issues in Re Marriage of Lugaresi: Alleged Human Trafficking Case Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James ToweryDokument135 SeitenRespondent's Statement of Issues in Re Marriage of Lugaresi: Alleged Human Trafficking Case Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James ToweryCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Disqualification of Judge John Ouderkirk - JAMS Private JudgeDokument11 SeitenAngelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Disqualification of Judge John Ouderkirk - JAMS Private JudgeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Order On Misconduct by Judge John OuderkirkDokument44 SeitenAngelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Order On Misconduct by Judge John OuderkirkCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Silicon Valley District Attorney Threatens Whistleblower Complaint Against Public Defender Over Protest Blog PostsDokument8 SeitenSilicon Valley District Attorney Threatens Whistleblower Complaint Against Public Defender Over Protest Blog PostsCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- "GENERAL ORDER RE: EXPRESSIVE ACTIVITY" Restricting Free Speech Outside Santa Clara County Courthouses Issued by Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas on February 22, 2017 - Civil Rights - Free Speech - Freedom of Association - Constitutional RightsDokument4 Seiten"GENERAL ORDER RE: EXPRESSIVE ACTIVITY" Restricting Free Speech Outside Santa Clara County Courthouses Issued by Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas on February 22, 2017 - Civil Rights - Free Speech - Freedom of Association - Constitutional RightsCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 US DOJ MOU With St. Louis County Family CourtDokument24 Seiten2016 US DOJ MOU With St. Louis County Family CourtCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prosecutorial Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney Subordinate Jay Boyarsky - Santa Clara CountyDokument2 SeitenProsecutorial Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney Subordinate Jay Boyarsky - Santa Clara CountyCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- District Attorney Jeff Rosen Misconduct: Santa Clara County District Attorney's Office - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeDokument1 SeiteDistrict Attorney Jeff Rosen Misconduct: Santa Clara County District Attorney's Office - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- DA Jeff Rosen Prosecutor Misconduct: Assistant DA Boyarsky Rebuked by Court - Santa Clara County - Silicon ValleyDokument4 SeitenDA Jeff Rosen Prosecutor Misconduct: Assistant DA Boyarsky Rebuked by Court - Santa Clara County - Silicon ValleyCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federal Class Action Lawsuit Against California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye For Illegal Use of Vexatious Litigant StatuteDokument55 SeitenFederal Class Action Lawsuit Against California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye For Illegal Use of Vexatious Litigant StatuteCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Prosecutor Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney of Santa Clara County Controversy - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeDokument1 SeiteProsecutor Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney of Santa Clara County Controversy - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terry Houghton and Valerie Houghton Felony Criminal Complaint and DocketDokument64 SeitenTerry Houghton and Valerie Houghton Felony Criminal Complaint and DocketCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Placing Children at Risk: Questionable Psychologists and Therapists in The Sacramento Family Court and Surrounding Counties - Karen Winner ReportDokument153 SeitenPlacing Children at Risk: Questionable Psychologists and Therapists in The Sacramento Family Court and Surrounding Counties - Karen Winner ReportCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas50% (2)

- Opposition to Motion to Dismiss (Trumbetta) Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California:: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Dokument4 SeitenOpposition to Motion to Dismiss (Trumbetta) Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California:: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- E.T. v. Ronald George Class Action Complaint USDC EDCADokument55 SeitenE.T. v. Ronald George Class Action Complaint USDC EDCACalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appellant'S Opening Brief: in The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaDokument50 SeitenAppellant'S Opening Brief: in The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion to Dismiss for Loss or Destruction of Evidence (Trombetta) Filed July 5, 2018 by Defendant Susan Bassi: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Dokument15 SeitenMotion to Dismiss for Loss or Destruction of Evidence (Trombetta) Filed July 5, 2018 by Defendant Susan Bassi: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (2)

- Opposition to Murgia Motion to Compel Discovery Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Dokument6 SeitenOpposition to Murgia Motion to Compel Discovery Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Profile of Justice Coleman A. Blease, California Appellate Courts - Third DistrictDokument3 SeitenProfile of Justice Coleman A. Blease, California Appellate Courts - Third DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federal Criminal Indictment - US v. Judge Joseph Boeckmann - Wire Fraud, Honest Services Fraud, Travel Act, Witness Tampering - US District Court Eastern District of ArkansasDokument13 SeitenFederal Criminal Indictment - US v. Judge Joseph Boeckmann - Wire Fraud, Honest Services Fraud, Travel Act, Witness Tampering - US District Court Eastern District of ArkansasCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judge Jack Komar: A Protocol For Change 2000 - Santa Clara County Superior Court Controversy - Judge Mary Ann GrilliDokument10 SeitenJudge Jack Komar: A Protocol For Change 2000 - Santa Clara County Superior Court Controversy - Judge Mary Ann GrilliCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judge Bruce Mills Misconduct Prosecution by the Commission on Judicial Performance: Report of the Special Masters: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law - Contra Costa County Superior Court Inquiry Concerning Judge Bruce Clayton Mills No. 201Dokument38 SeitenJudge Bruce Mills Misconduct Prosecution by the Commission on Judicial Performance: Report of the Special Masters: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law - Contra Costa County Superior Court Inquiry Concerning Judge Bruce Clayton Mills No. 201California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Garrett Dailey Attorney Misconduct - Perjury Allegations in Marriage of Brooks - Attorney Bradford Baugh, Joseph RussielloDokument2 SeitenGarrett Dailey Attorney Misconduct - Perjury Allegations in Marriage of Brooks - Attorney Bradford Baugh, Joseph RussielloCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judicial Profile: Coleman Blease, 3rd District Court of Appeal CaliforniaDokument3 SeitenJudicial Profile: Coleman Blease, 3rd District Court of Appeal CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Third Appellate DistrictDokument13 SeitenIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Third Appellate DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantDokument4 SeitenIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Appellant'S Reply BriefDokument19 SeitenIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Appellant'S Reply BriefCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- 3rd Appellate District Change Court: Court Data Last Updated: 03/26/2017 08:40 AMDokument9 Seiten3rd Appellate District Change Court: Court Data Last Updated: 03/26/2017 08:40 AMCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaDokument9 SeitenIn The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qeourt of Peal of TBT S Tatt of Qealifomia: Third Appellate DistrictDokument2 SeitenQeourt of Peal of TBT S Tatt of Qealifomia: Third Appellate DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMU Moot RespondentDokument31 SeitenAMU Moot Respondentmamta50% (2)

- R V MohanDokument10 SeitenR V Mohanmuzhaffar_razak100% (1)

- People vs. SilvaDokument31 SeitenPeople vs. SilvaFlo PaynoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torts - RestatementsDokument38 SeitenTorts - RestatementsElla Devine0% (1)

- Application of PenaltiesDokument9 SeitenApplication of Penaltiesrascille laranasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 Ysidoro V PeopleDokument2 Seiten8 Ysidoro V PeopleAlexandraSoledad100% (1)

- US vs Go Chico: Criminal Intent Not RequiredDokument7 SeitenUS vs Go Chico: Criminal Intent Not RequiredEcnerolAicnelavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kle Law Academy Belagavi: Study MaterialDokument131 SeitenKle Law Academy Belagavi: Study MaterialShriya JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tort Law OutlineDokument11 SeitenTort Law Outlinekinsleyharper100% (1)

- People v. Puig Ruling on Sufficiency of 112 Informations for Qualified TheftDokument2 SeitenPeople v. Puig Ruling on Sufficiency of 112 Informations for Qualified Theftlim_danielleNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs LanuzaDokument1 SeitePeople Vs LanuzamenforeverNoch keine Bewertungen

- B V DPP (2000) 2 AC 428 House of LordsDokument3 SeitenB V DPP (2000) 2 AC 428 House of LordsDevika KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal AttemptsDokument32 SeitenCriminal AttemptsViren SehgalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 07 Crimes Against PersonsDokument86 Seiten07 Crimes Against PersonsGeanibev De la CalzadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Villareal vs. PeopleDokument11 SeitenVillareal vs. PeopleJan Carlo SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuates V Bersamin DigestDokument1 SeiteTuates V Bersamin DigestDenise GordonNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Mauricio Londono-Villa, 930 F.2d 994, 2d Cir. (1991)Dokument15 SeitenUnited States v. Mauricio Londono-Villa, 930 F.2d 994, 2d Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Title 3 February 10, 2018Dokument202 SeitenTitle 3 February 10, 2018Westly JucoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 22Dokument11 Seiten1 22Vin SabNoch keine Bewertungen