Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Urban Nature Benefits

Hochgeladen von

sile15Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Urban Nature Benefits

Hochgeladen von

sile15Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CENTER

for U R B A N H O RT I C U LT U R E

University of Washington, College of Forest Resources

HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF THE URBAN FOREST

FACT SHEET #1

Urban Nature Benefits:

Psycho-Social Dimensions of People and Plants

America is a nation of cities and towns more than 80 percent

of the U.S. population lives in urban areas. Plants, forests and

ecosystems are important in cities. People are working in many

cities to preserve existing natural areas and restore or create

new ones. Scientific research tells us that urban plants provide

many benefits. We know that plants improve the environment

by contributing to better air and water quality and helping to

reduce energy use.

Social scientists study another level of services that plants provide for urban residents. Parks, green spaces and trees are more

than the lungs of the city or pollution scrubbers. They affect

our everyday moods, activities and emotional health. They

improve our quality of life in ways that are sometimes understood, often underestimated. Whether we are active in urban nature (planting trees, growing gardens) or passively encounter city green (such as a stroll through a park), we experience personal

benefits that affect how we feel and function. Proof of psychological and social benefits gives us

more reasons to grow more green in cities! Below are examples from many studies.

Individual Benefits

Urban life can be demanding juggling schedules, work,

meeting daily needs and commuting. Our urban open

spaces and parks can provide welcome relief, in surprising ways. Everyday nature in cities can help us to calm

and cope, to recharge our ability to carry on.

shown that brief encounters with nature can aid cognitive fatigue recovery, improving ones capacity to concentrate. Psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan define

the characteristics of natural places that are restorative being away, extent, fascination and compatibility.

RESTORATIVE EXPERIENCES Many of the tasks

of work and study demand directed attention for long

periods of time. As we psychologically filter out extraneous information and distractions our minds can become

cognitively fatigued. Directed attention fatigue can

result in feelings of anxiety or stress, irritability with

others and an inability to concentrate. Research has

WORKER ATTITUDES AND WELL-BEING Dr.

Rachel Kaplan surveyed deskworkers about their rate of

illness and level of job satisfaction. Some study participants could view nature from their desks, others could

not. Those without, when asked about 11 different

ailments, claimed 23% more times of illness in the prior

six months. Desk workers with a view claimed the

following satisfactions more often than their non-view

colleagues: 1) found their job more challenging, 2) were

less frustrated about tasks and generally more patient,

3) felt greater enthusiasm for the job, 4) reported

feelings of higher life satisfaction, and 5) reported better

overall health.

STRESS REDUCTION Stress is often talked about

but little understood. We do know that constant stress

can impact our immune system as well as diminish the

ability to cope with challenging situations. Roger Ulrich

has done studies that measure the physiological responses of our bodies (such as blood pressure and heart

rate) brought on by stress. He has found that people

who view nature after stressful situations show reduced

physiological stress response, as well as better interest

and attention and decreased feelings of fear and anger or

aggression. An interesting effect found in recent studies

on driving and road stress is called the immunization

effect the degree of negative response to a stressful

experience is less if a view of nature preceded the

stressful situation.

Families, Children and Youth

Our families and young people are the foundation and

future of our society. Many factors, including adequate

education and health care, are essential for their strength

and success. In addition, children and families need

supportive environments that encourage positive

behaviors and provide a respite from the challenges of

urban living. Recent research reveals the subtle advantages of urban green spaces.

REDUCED DOMESTIC CONFLICT Surveys of

households in Chicagos public housing have explored

the role of trees on household interpersonal dynamics.

The housing projects apartment buildings are nearly

identical, differing only in the amount of trees and grass

growing around them. Drs. Bill Sullivan and Francis Kuo

report that residents living in buildings with trees use

more constructive, less violent methods to deal with

conflict. Residents with green views report using

reasoning more often in conflicts with their children and

significantly less use of severe violence. They also report

less use of physical violence in conflicts with partners

compared to those living in buildings without trees.

LESS SCHOOL AGGRESSION AND VIOLENCE

School violence programs help students to control

aggressive behavior with training in conflict resolution

and peer intervention. Physical environments around a

school also appear to play a role. Education scientists at

the University of Michigan have found that scenes of

neighborhoods with blighted streetscapes are perceived

as dangerous and threatening. Those that are more

cared for, including tended landscapes, contribute to

reduced feelings of fear and violence.

REFERENCES AND RESOURCES

Dwyer, J.F., H.W. Schroeder, & P. H. Gobster. 1994. The Deep Significance of Urban Trees and Forests. In R.H. Platt, R.A. Rowntree, P.C. Muick

(editors), The Ecological City: Preserving & Restoring Urban Biodiversity. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Kaplan, R. & S. Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, C. A. 1996. Green Nature/Human Nature: The Meaning of Plants in our Lives. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Relf, D. (editor). 1992. The Role of Horticulture in Human Well-Being and Social Development. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

For more information, contact

Kathy Wolf, Ph.D. at the

Center for Urban Horticulture, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-4115

Phone: (206) 616-5758; Fax: (206) 685-2692;

E-mail: kwolf@u.washington.edu; Web site: www.cfr.washington.edu/enviro-mind

KL WOLF NOVEMBER 1998

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Building MaterialDokument11 SeitenBuilding Materialsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- ToolDokument7 SeitenToolsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Book - Construction Equipment GuideDokument1 SeiteBook - Construction Equipment Guidesile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Site Manager Job DescriptionDokument4 SeitenSite Manager Job Descriptionsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Site ManagerDokument2 SeitenSite Managersile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Using Work Equipment Safely PDFDokument9 SeitenUsing Work Equipment Safely PDFsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Skilled WorkerDokument5 SeitenSkilled Workersile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Power tools guideDokument4 SeitenPower tools guidesile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Built EnvironmentDokument4 SeitenBuilt Environmentsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Machine ToolDokument9 SeitenMachine Toolsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Powered Hand ToolsDokument4 SeitenPowered Hand Toolssile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Built EnvironmentDokument4 SeitenBuilt Environmentsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Heavy Equipment GuideDokument16 SeitenHeavy Equipment Guidesile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- CDC - Easy Ergonomics - A Guide To Selecting Non - Hand Tool2Dokument20 SeitenCDC - Easy Ergonomics - A Guide To Selecting Non - Hand Tool2AliceAlormenuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hand Tool History and Uses in 40 CharactersDokument2 SeitenHand Tool History and Uses in 40 Characterssile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Construction Work V1Dokument52 SeitenConstruction Work V1sile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Using Work Equipment Safely PDFDokument9 SeitenUsing Work Equipment Safely PDFsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Building MaterialDokument11 SeitenBuilding Materialsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Trimester PlannerDokument1 SeiteTrimester Plannersile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Book - Construction Equipment GuideDokument1 SeiteBook - Construction Equipment Guidesile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- 27Dokument6 Seiten27sile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Transactional AnalysisDokument60 SeitenTransactional AnalysispdenycNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of BuildingDokument3 SeitenTypes of Buildingsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cost Control, Monitoring and AccountingDokument32 SeitenCost Control, Monitoring and Accountingsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Single Storey Industrial BuildingsDokument52 SeitenSingle Storey Industrial Buildingssile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Single Storey Industrial BuildingsDokument52 SeitenSingle Storey Industrial Buildingssile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Weekly Planner: Study SkillsDokument2 SeitenWeekly Planner: Study Skillssile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Transactional AnalysisDokument49 SeitenTransactional Analysissile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Transactional Analysis PDFDokument15 SeitenTransactional Analysis PDFsile15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Baseline For Setting Out TheodoliteDokument70 SeitenBaseline For Setting Out Theodolitemitualves100% (5)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Psy202-2021 Dissociative DisordersDokument4 SeitenPsy202-2021 Dissociative DisordersJustin TayabanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argumentative EssayDokument1 SeiteArgumentative EssayGene Gerard Baluca BaculpoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Empathy Map Canvas 006 PDFDokument1 SeiteEmpathy Map Canvas 006 PDFSam Sy-HenaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 - Common Psychiatric Problems - Mubarak-SubaieDokument62 Seiten7 - Common Psychiatric Problems - Mubarak-SubaieLavitSutcharitkulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group Process: Occupational Therapy Tool of PracticeDokument25 SeitenGroup Process: Occupational Therapy Tool of Practiceemesep18Noch keine Bewertungen

- How Stressed Are You?: Instructions: The Questions in This Scale Ask About Your Thoughts andDokument2 SeitenHow Stressed Are You?: Instructions: The Questions in This Scale Ask About Your Thoughts andJustine BuhiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Duke Informal2Dokument5 SeitenDuke Informal2api-315684723Noch keine Bewertungen

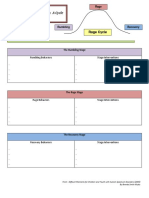

- Rumbling Rage Recovery InfographicDokument4 SeitenRumbling Rage Recovery Infographicapi-247044545Noch keine Bewertungen

- Internet AddictionDokument2 SeitenInternet Addictionslavica_volkanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kristine - Part4-Unit 4.1 Motivation PDFDokument8 SeitenKristine - Part4-Unit 4.1 Motivation PDFKristine Mangundayao100% (1)

- Basic Techniques in Marriage and Family Counseling and Therapy. Eric DigestDokument4 SeitenBasic Techniques in Marriage and Family Counseling and Therapy. Eric DigestSabrina PBNoch keine Bewertungen

- Depression ResearchDokument1 SeiteDepression ResearchKlare MillerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical and Forensic Interviewing Sattler JeromeDokument9 SeitenClinical and Forensic Interviewing Sattler Jeromeraphael840% (1)

- Barrett Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)Dokument10 SeitenBarrett Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)andr3yl0Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jennifer Droski: L.L.M.S.WDokument3 SeitenJennifer Droski: L.L.M.S.Wapi-453860161Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aspire Issue 6Dokument41 SeitenAspire Issue 6HelenNoch keine Bewertungen

- DSM 1Dokument2 SeitenDSM 1Csvv VardhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Intervention Protocol 1Dokument5 SeitenFinal Intervention Protocol 1api-333354952Noch keine Bewertungen

- Quotes by Milton EricksonDokument2 SeitenQuotes by Milton Ericksongiovana14Noch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation EmotionsDokument25 SeitenPresentation EmotionsAkshay SirDeshpandeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dance Therapy TortureDokument15 SeitenDance Therapy TortureeclatantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why The NHS Must ChangeDokument2 SeitenWhy The NHS Must ChangeMark HayesNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECT TREATMENT HISTORY, INDICATIONS, AND PROCEDUREDokument28 SeitenECT TREATMENT HISTORY, INDICATIONS, AND PROCEDUREsrinivasanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sport Psychology: Sabrina JefferyDokument13 SeitenSport Psychology: Sabrina Jefferycsarimah csarimah100% (1)

- Peace Corps Eating Disorder Treatment Summary Form PC-262-8 (Initial Approval 08/2012Dokument4 SeitenPeace Corps Eating Disorder Treatment Summary Form PC-262-8 (Initial Approval 08/2012Accessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Profiles Best Revised Matrix 2010Dokument2 SeitenProfiles Best Revised Matrix 2010api-235377542Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2019-2020 Sanderson High School Toy NominationsDokument5 Seiten2019-2020 Sanderson High School Toy Nominationsapi-472827294Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gratitude JournalDokument31 SeitenGratitude Journalmanchiraju raj kumar100% (1)

- Maslach Burnout Inventory Mbi PDFDokument3 SeitenMaslach Burnout Inventory Mbi PDFRina Fitriani50% (2)

- Nursing AssessmentDokument2 SeitenNursing AssessmentCarmena IngenteNoch keine Bewertungen