Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Tech Spillovers

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous jnG2gQEbHOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Tech Spillovers

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous jnG2gQEbHCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

World Economy Technology Spillovers

technology spillovers

Technology spillovers are the beneficial effects of new technological knowledge on the

productivity and innovative ability of other firms and countries. Technology is nonrival: ones use of a technology does not limit its use by others and the cost for an

additional agent to use an existing technology is negligible compared to the cost of

inventing it. Hence, not all the benefits of technological knowledge are appropriated by

the inventor; technological investments typically generate social returns that far outweigh

private returns. Technology, once invented, can be used and diffused internationally with

small added cost but substantial added benefit.

Technological research and innovation is mostly undertaken by firms and

governments in the leading world economies that are also the world technological

leaders. Then technology diffuses to the rest of the world though the main channels of

trade, migration, foreign direct investment (FDI), and technological licensing (patents

and copyrights).

International technology spillovers have received much attention in the recent

economic research both from theoretical and empirical perspectives. Theory identifies

them as a key mechanism for the sustained growth of productivity and its diffusion across

countries. From an empirical point of view, economists have studied how to measure

technology spillovers and what channels are conducive to them. From a policy point of

view, countries desiring greater technology spillovers use policies to promote trade and

FDI and to promote better conditions for taking advantage of spillovers by absorbing

them into domestic productivity gains.

World Economy Technology Spillovers

Theory of Technology Spillovers

Recent theories of economic growth and income differences across countries (see Eaton

and Kortum 2002 and Klenow and Rodriguez-Clare 2005 for reviews) identify available

technological and scientific knowledge as the most important determinants of

productivity in a country. Scientific and technological innovation are the main engines of

productivity growth in the rich countries (Europe, Japan, and North America). Their

diffusion to industrializing countries, accompanied by investments in physical and human

capital, is the main reason for the growth in productivity and income per capita of those

economies. Yet some countries seem stuck far behind the technology frontier. The

process of technological diffusion has a central position in the recent literature on

development and growth. A better understanding of the nature of technology spillovers

should help shed light on why some countries grow faster than others.

Due to its non-rival nature, technological knowledge can be used by producers

other than the inventor to increase their productivity. Hence it generates two types of

benefits called spillovers.

i)

First, new technological knowledge can be used in any country to produce

more efficiently or higher quality goods. This spillover increases the labor

productivity of the country that adopts it.

ii)

Second, technological knowledge can be used in any country to produce new

ideas or new applications in research and development (R&D). This increases

R&D effectiveness in receiving countries.

Inventors usually appropriate at least part of the benefits from the first type of spillovers,

either by producing goods with the new technology and exporting them to foreign

World Economy Technology Spillovers

markets (trade) or by setting up production that uses the new technology in other

countries (FDI) or by licensing out the new technology and receiving royalty payments

for it. International trade, FDI and international patents and copyrights are therefore

common channels for diffusing the benefits of technological innovations to consumers in

other countries. At the same time those flows carry the knowledge related to the new

technology either embodied in goods, or in machines, or in instructions. This new

knowledge enables receiving countries to benefit from the second type of technological

spillovers: other firms and producers may learn and improve their productivity as a

consequence of exposure to better technology. The first type of technology spillovers are

usually mediated by market mechanisms (trade, investments and intellectual property

rights) and are sometimes called technology diffusion. The second type of technology

spillovers involve diffusion of knowledge to other firms of the receiving country via

mobility of workers, learning, imitation, sub-contracting and are considered technology

externalities.

In the light of these beneficial effects on productivity and growth, international

technological spillovers (even more than international trade of goods and international

movements of capital per se) have been identified as potentially the most beneficial

aspect of globalization. The empirical research has consequently focused on measuring

the intensity, quantifying the effects and identifying the most relevant channels of these

spillovers. At the same time researchers and policy makers have analyzed what are the

characteristics that make a receiving country best positioned to receive the benefits from

those spillovers.

World Economy Technology Spillovers

Empirical Analysis of International Technology Spillovers

Technology spillovers are not recorded in the data. However the channels of their

transmission (trade, FDI, patents) and their consequences (productivity benefits) can be

recorded and measured. The recent empirical analysis has used a plurality of data and

approaches to qualify and quantify the intensity and productive impact of those spillovers

across countries.

Measuring Technology Spillovers

Technological and scientific knowledge is an intangible asset not measurable directly.

Economists have used measures of R&D resources (input) or measures of innovations

such as patents or productivity (output) to approximate it. Aggregate studies have used

country-level data, while micro studies have used firm-level data. Two general methods

are used to identify spillovers. The first method considers the effects of R&D done in

some countries (or firms) on the productivity of other countries (or firms) that are linked

to the former via trade, FDI, or technological/geographical proximity. The basic features

of this approach were first developed in a very influential paper by Coe and Helpman

(1995) and will be described in the next section. The second approach considers directly

the association between the presence/intensity of trade and FDI (channels of technology

spillovers) and the productivity of the importing/receiving country or firms there. Both

methods infer the existence of spillovers indirectly from the effects on productivity in

firms of the receiving economy.

A third approach aimed at identifying more directly the linkages that reveal

technology spillovers, analyzes citations from a patent to previous patents considering

them as tangible sign of a knowledge spillover (Jaffe and Trajtenberg 2002). An existing

World Economy Technology Spillovers

idea recorded in a patent contributes to the development of a new idea (new patent), and

the citation link reveals this spillover. This method isolates only spillovers of the second

type described above (from R&D to R&D) and tends to emphasize the geographic

localization of those technology spillovers. This method complements (but cannot

substitute for) the other type of studies, as it only identifies the intensity and

characteristics of technological spillovers but cannot quantify their impact on

productivity.

Trade and Technology Spillovers

A popular approach for analyzing the presence and the intensity of technology spillovers

has been to analyze the association (correlation) between productivity in country j (or

industry or firm) and the R&D activity in countries (industries or firms) other than j that

are linked to j by potential channels of spillovers. The basic empirical procedure,

presented in Coe and Helpman (1995) and expanded and updated since then, is to

estimate some version of the following regression: Productivityj = Function(Xj, R&Dj,

R&Dspillovers). The variable Productivityj represents some measure of the productivity

(usually total factor productivity or labor productivity) of country (industry, firm) j. The

vector Xj is an array of country (industry, firm) characteristics relevant for its

productivity. R&Dj is a measure of research and development activity performed in the

country (industry, firm) j and R&Dspillovers=

m R & D

i j

is a weighted sum of R&D

activity in other countries. The key feature that identifies this term as capturing

technology spillovers is that the weights mi are constructed to reflect the intensity of

potential spillover channels between country (industry, firm) j, the receiver, and country

(sector, firm) i, the sender. In the original work of Coe and Helpman (1995) mi was

World Economy Technology Spillovers

measured as the share of imports from country j among trade partner of country i

assuming that imports are the most relevant channel of technology spillovers. Subsequent

research has experimented with different weights to capture other potential spillover

channels. Some alternative measures of mi have been the share of FDI from country j in

total capital formation of country i, the share of imports of capital goods (rather than all

goods) and the share of direct and indirect trade (i.e. trade through third-country

mediation). More recently Keller (2002) has constructed the weights mi based on

geographical proximity between country j and i. This approach is based on the

assumption that a whole array of potential spillover channels (trade, FDI, migration,

technological licensing, business travel and others) are strongly enhanced by

geographical proximity. A popular variation of the approach described above, mostly

used on individual firm data, is to measure the effect of technological spillovers on

production costs rather than productivity.

The limit of this type of approach is that the identification of externalities is based

on correlations and it is not easy to establish a real causation link. To address the limits of

the reduced form approach, recent research by Jonathan Eaton and Samuel Kortum has

studied the relationship between R&D technology diffusion and domestic productivity in

the context of general equilibrium models. In those models one can analyze and simulate

the impact of increased research and trade liberalization on technology spillovers and

productivity.

Overall the findings of this literature point to two rather robustly estimated

regularities. First, the effect of R&D spillovers on productivity is consistently larger than

zero and significantly positive for the average OECD country. Second, while for the

World Economy Technology Spillovers

leading economies (G-7 countries), the impact of domestic R&D on productivity is

consistently larger than the spillover effects from other countries, for smaller and less

advanced economies (other OECD countries) the impact of spillovers is larger than the

impact of domestic R&D on productivity. These findings confirm that technological

leaders tend to perform most of the R&D and innovation in the world and spillovers from

those technologies are a major source of productivity growth for other countries.

FDI and Technology Spillovers

A second approach to identifying and quantifying international technology spillovers is

based on the idea that FDI is an explicit activity set up to transfer technology across

national borders (e.g. Markusen, 2002). Hence FDI is a direct carrier of technology flows.

The question is how much these flows benefit the productivity of the receiving economy

and what are the features or policies of the receiving economy that enhance the positive

effects of technology spillovers. Several theoretical models argue that multinational

enterprises should generate technology spillovers to local firms through several channels

and many of them have been studied in detail using firm-level data. Imitation, learning,

and acquisition of human capital through worker turnover are considered as the most

important channels of spillovers. Competition, sub-contracting and supply of high quality

intermediate inputs are market-mediated mechanisms that make better inputs available to

the local firms, stimulate more efficient technologies, and may also have positive

productivity effects.

The typical empirical approach for identifying technological spillovers through

FDI estimates the following model: Productivityjk = Function(Xj, FDIk). The term

(Productivityjk) measures the productivity of firm j in sector k and the right hand side of

World Economy Technology Spillovers

the expression implies that it is a function of a vector of firm characteristics Xj and of

some measure (usually the share of employment or of sales) of the presence of

multinational enterprises in sector k, (FDIk). Usually these studies analyze firm-level data

for one country at a time (hence no country subscript) and often they consider

geographical proximity as a requisite for (or enhancer of) the technology spillovers:

multinationals have larger productivity effects if they are located in the same region or

area as the potential spillover-receiving firm j. Another relevant dimension of the

spillovers is whether they benefit domestic firms horizontally, namely those in the

same industry or vertically, namely those that supply inputs to or buy inputs from the

multinational enterprise.

Using cross-section and panel data from several different industrialized and

industrializing countries, many researchers have estimated technology spillovers through

FDI using the method described above. Interestingly, the evidence in favor of positive

effects of technology spillovers on productivity of domestic firms is scant, especially

when considering developing countries. Blomstrom and Kokko (1998) and more recently

Gorg and Greenway (2004) review dozens of such studies and conclude robust evidence

of positive effects of FDI spillovers is found mainly for industrialized countries. For

developing countries results are much less clear. A typical example of those studies is the

influential article by Aitken and Harrison (1999) that analyzing evidence from FDI in

Venezuela does not find any positive effect on productivity of local firms. In fact the

study finds some negative effects on domestic firms and attributes them to increased

competition from FDI and crowding out of domestic firms.

Absorptive Capacity

World Economy Technology Spillovers

These findings have prompted research on the role of the receiving firm or country in

determining the impact of technology spillovers. While the potential for technology

spillovers is intrinsic to FDI activity, the actual impact on productivity of domestic firms

depends on the absorptive capacity of those firms. Human capital and investment in R&D

by the receiving country (firm) are important pre-requisite to experience positive effect of

technology spillovers on productivity. Insufficient human capital in local firms could be

the explanation for the lack of spillovers from FDI in developing countries. Using firmlevel data, several articles (e.g. Glass and Saggi, 1998) confirm that firms using low

skilled workers and backward technology are unable to benefit from FDI technology

spillovers.

Conclusion and Policy Considerations

Foreign direct investments are seen by government of several industrializing countries, as

highly beneficial to the domestic economy. Technology spillovers are only one of their

effects, as those investments bring also employment opportunities, higher consumption

and higher government income. However technological spillovers generate probably the

most important and lasting effects in the long run as they channel technological transfer

and induce productivity growth. In the light of the empirical findings, policies promoting

higher education and skill-formation of workers and R&D investment of domestic firms

are needed complements to policies that attract FDI, if a country is to maximize the

absorption of technological spillovers. At the same time some policies such as R&D

requirements, technology transfer requirements and local hiring targets on multinational

enterprises can increase the intensity of technological activity and the benefits for the

World Economy Technology Spillovers

10

local economy. Probably, however, a general framework of openness towards

international flows and free competition in trade, FDI and technological licensing is the

most important component for a country to attract technology spillovers and benefit from

improved technologies as they become available to the global economy.

Annotated References

Aitken, Brian, and Ann Harrison. 1999. Do Domestic Firms Benefit from Foreign Direct

Investment? Evidence from Venezuela. American Economic Review 89(3): 60518. One of the most cited and influential articles on FDI spillovers in developing

countries.

Blomstrom, Magnus, and Ari Kokko. 1998. Multinational Corporations and Spillovers.

Journal of Economic Surveys 12(3): 247-77. An early comprehensive survey of

the literature on FDI and technology spillovers

Coe, David, and Elhanan Helpman. 1995. International R&D Spillovers. European

Economic Review 39(5): 859-87. The initial and still one of the most influential

articles on trade and technology spillovers

Eaton, Jonathan, and Samuel Kortum. 2002. Technology, Geography and Trade.

Econometrica 70(5): 1741-79. A sophisticated theoretical and empirical analysis

of technological diffusion and technology spillovers.

Glass, Amy, and Kamal Saggi. 1998. International Technology Transfer and the

Technology Gap. Journal of Development Economics 55(2): 369-98. One of the

most influential recent articles on the role of absorptive capacity in determining

the impact of FDI spillovers.

10

World Economy Technology Spillovers

11

Gorg, Holger, and David Greenway. 2004. " Much Ado About Nothing? Do Domestic

Firms Really Benefit From Foreign Direct Investment?" World Bank Research

Observer 19(2): 171-97. The most comprehensive recent review of the role of

FDI in promoting technological spillovers.

Jaffe, Adam, and Manuel Trajtenberg. 2002. Patents Citations and Innovations. A

Window on the Knowledge Economy. Cambridge Ma, MIT Press. The most

comprehensive collection of research on the use of patent data and patent citations

to measure technology spillovers.

Keller, Wolfgang. 2002. Geographic Localization and International Technology

Diffusion. American Economic Review 92 (1): 120-42. A very influential paper

measuring the importance of geographical proximity for technological diffusion.

Keller, Wolfgang. 2004. International Technology Diffusion. Journal of Economic

Literature 42(3): 752-82. A comprehensive literature review on international

technology diffusion.

Klenow, Peter and Andres Rodriguez-Clare. 2005. Externalities and Growth. In Aghion

Philippe and Steven Durlauf ed. The Handbook of Economic Growth. Amsterdam

Elsevier. An excellent review of the most relevant theoretical models of

technological spillovers and economic growth.

Markusen James. 2002. Multinational Firms and the Theory of International Trade.

Cambridge Ma, MIT Press.

A very influential, mostly theoretical, book on multinational firms and international trade

11

World Economy Technology Spillovers

12

Giovanni Peri

Department of Economics, University of California, Davis and NBER

Bio:

Giovanni Peri is Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, Davis

and Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received his

Ph.D. in UC Berkeley and he does research in the fields of International Technological

Diffusion, Human Capital, International Migrations and Productivity. He has published

in several internationally refereed journals such as the Review of Economic Studies,

Review of Economics and Statistics, Economic Journal, and European Economic Review.

12

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Intellectual Property and Innovation Protection: New Practices and New Policy IssuesVon EverandIntellectual Property and Innovation Protection: New Practices and New Policy IssuesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transnational Corporations, Technology Transfer and Development: A Bibliographic SourcebookVon EverandTransnational Corporations, Technology Transfer and Development: A Bibliographic SourcebookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intellectual Property Rights and The International Transfer of Technology: Setting Out An Agenda For Empirical Research in Developing CountriesDokument24 SeitenIntellectual Property Rights and The International Transfer of Technology: Setting Out An Agenda For Empirical Research in Developing Countriesravi242Noch keine Bewertungen

- Colantone Slides Lectures 1 2Dokument56 SeitenColantone Slides Lectures 1 2bog.creeperaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technology Transfer From Public Research OrganizationsDokument15 SeitenTechnology Transfer From Public Research OrganizationsFarooqChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.1 Models by CountryDokument18 Seiten1.1 Models by CountrymhldcnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daniele Archibugi and Carlo PietrobelliDokument20 SeitenDaniele Archibugi and Carlo PietrobelliPaulo GeneraloNoch keine Bewertungen

- D R U I D: Globalisation of Innovation: The Role of Multinational EnterprisesDokument37 SeitenD R U I D: Globalisation of Innovation: The Role of Multinational EnterprisesМилош МујовићNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Research Paper IgDokument12 SeitenFinal Research Paper IgjoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innovation in Manufacturing: The Role of Foreign Technology Transfer and External NetworkingDokument31 SeitenInnovation in Manufacturing: The Role of Foreign Technology Transfer and External NetworkingJuanJulio GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rohrbeck (2006) Technology-Scouting PaperDokument15 SeitenRohrbeck (2006) Technology-Scouting PaperHector OliverNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer of Technology To Developing Countries: Unilateral and Multilateral Policy OptionsDokument37 SeitenTransfer of Technology To Developing Countries: Unilateral and Multilateral Policy OptionskhaldoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Identifying20spillovers PDFDokument37 SeitenIdentifying20spillovers PDFApip SupriadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 FDI Much Ado About Nothing Do Domestic Firms Really Benefit From Foreign Direct InvestmentDokument28 Seiten1 FDI Much Ado About Nothing Do Domestic Firms Really Benefit From Foreign Direct InvestmentSaid SalehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research in Economics: João Tovar JallesDokument16 SeitenResearch in Economics: João Tovar JallesM SukmanegaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Background Report For World Development Report 2000/2001Dokument11 SeitenBackground Report For World Development Report 2000/2001Michel Monkam MboueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technology TransferDokument54 SeitenTechnology TransferJasmeet SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technology and Economic DevelopmentDokument5 SeitenTechnology and Economic DevelopmentSarose ThapaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Technology On International Arbitration and The Nature of Substantive Claims Asserted in International ArbitrationDokument2 SeitenThe Impact of Technology On International Arbitration and The Nature of Substantive Claims Asserted in International Arbitrationpalak asatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- BELL - & - PAVITT - Technological Accumulation and Industrial GrowthDokument54 SeitenBELL - & - PAVITT - Technological Accumulation and Industrial GrowthJasar GraçaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Globalization of Market 4Dokument2 SeitenGlobalization of Market 4Adigun OlamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of The Technology Transfers and InnovationsDokument9 SeitenAnalysis of The Technology Transfers and InnovationsExekiel Albert Yee TulioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4.transnational Companies and Their Technological Power Investments in Technology Development and Technology TransferDokument14 Seiten4.transnational Companies and Their Technological Power Investments in Technology Development and Technology TransferrosanacarvalhopaivaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The ICT RevolutionDokument26 SeitenThe ICT Revolutionlouis_alfaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Management of TechnologyDokument39 SeitenChapter 1 Introduction To Management of TechnologyNeelRaj75% (8)

- Activity Essay PDFDokument1 SeiteActivity Essay PDFRAIZEN LANIPA OBODNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chen & Puttitanun (2004) Intellectual Property Rights and InnovationDokument20 SeitenChen & Puttitanun (2004) Intellectual Property Rights and InnovationAntonio MuñozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Production SharingDokument40 SeitenGlobal Production SharingAlexandra RonaldinHaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change & Technology Transfer: Addressing Intellectual Property IssuesDokument22 SeitenClimate Change & Technology Transfer: Addressing Intellectual Property IssuesRicha KesarwaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discussion Paper SeriesDokument60 SeitenDiscussion Paper SeriesNuwan Tharanga LiyanageNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bell and Pavitt 1993 Technological Accumulation and Industrial GrowthDokument54 SeitenBell and Pavitt 1993 Technological Accumulation and Industrial GrowthAna Paula Azevedo100% (2)

- Technology Development Programmes and Behaviour of Firms Proposal For M. Phil DissertationDokument6 SeitenTechnology Development Programmes and Behaviour of Firms Proposal For M. Phil Dissertationanil427Noch keine Bewertungen

- 4.3.c-Technology and IndustrializationDokument23 Seiten4.3.c-Technology and Industrializationjjamppong09Noch keine Bewertungen

- Innovation Vis-À-Vis Patenting Process A Legal StudyDokument2 SeitenInnovation Vis-À-Vis Patenting Process A Legal StudyBHARATH JAJUNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Trade and FDI Policies On Technology Adoption and Sourcing of Chinese FirmsDokument29 SeitenThe Impact of Trade and FDI Policies On Technology Adoption and Sourcing of Chinese FirmsBilal SattarNoch keine Bewertungen

- He Effects of Technological ChangeDokument11 SeitenHe Effects of Technological ChangeMarc Joseph LumbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research PaperDokument27 SeitenResearch Papermelba5Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1.international Linkages and Productivity at The Plant Level Foreign Direct Investment, Exports, Imports and LicensingDokument31 Seiten1.international Linkages and Productivity at The Plant Level Foreign Direct Investment, Exports, Imports and LicensingAzan RasheedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taylor - 2009 - Conclusion International Political Economy-The Reverse Salient of Innovation TheoryDokument5 SeitenTaylor - 2009 - Conclusion International Political Economy-The Reverse Salient of Innovation TheoryRaffi TchakerianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development, Research, Invention, Innovation, Technology, PatentsDokument16 SeitenDevelopment, Research, Invention, Innovation, Technology, PatentsDeepanshu AggarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSDS 207 Assignment 2 March 2022Dokument9 SeitenBSDS 207 Assignment 2 March 2022Emmanuel M. ChiwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 - Universities and National DevelopmentDokument13 SeitenModule 1 - Universities and National DevelopmentTOBI JASPER WANGNoch keine Bewertungen

- 019hawash Lang2010Dokument22 Seiten019hawash Lang2010Jean-Loïc BinamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technological Dimension of GlobalizationDokument19 SeitenTechnological Dimension of Globalizationfelbert DecanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study Guide Undp by SDCTMDokument18 SeitenStudy Guide Undp by SDCTMakakakakaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of MNC's in Transfering TechnologyDokument42 SeitenRole of MNC's in Transfering TechnologyOsman Gani100% (3)

- Prepared By: Bilisuma Teshome ID NO: DDU1002308: Submitted To: Ins. Debosha A. SUBMISSION DATE: 3-6-2022G.CDokument11 SeitenPrepared By: Bilisuma Teshome ID NO: DDU1002308: Submitted To: Ins. Debosha A. SUBMISSION DATE: 3-6-2022G.CTmichael MogesNoch keine Bewertungen

- InternatDokument31 SeitenInternatMOATH GAMEINGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sajid Anwar & Lan Phi Nguyen: Foreign Direct Investment As A Conduit For Technology Transfer: The Case of VietnamDokument18 SeitenSajid Anwar & Lan Phi Nguyen: Foreign Direct Investment As A Conduit For Technology Transfer: The Case of VietnamNguyễn Ái NươngNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7c542c16 en Páginas 1 16 PDFDokument16 Seiten7c542c16 en Páginas 1 16 PDFJohanna AriasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trouble in The Making The Future of ManufacturingDokument29 SeitenTrouble in The Making The Future of ManufacturingKim Premier MLNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Economics of Technology Diffusion: Implications For Greenhouse Gas Mitigation in Developing CountriesDokument10 SeitenThe Economics of Technology Diffusion: Implications For Greenhouse Gas Mitigation in Developing CountriesCesar OsorioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Determinants of High-Technology Exports A Panel Data AnalysisDokument12 SeitenThe Determinants of High-Technology Exports A Panel Data AnalysisOlah AlexandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technological EnvironmentDokument33 SeitenTechnological Environmentnewspaper_geo100% (1)

- Max Von... R&D Strategies, China - 0Dokument4 SeitenMax Von... R&D Strategies, China - 0Pavan KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Aggregate and Complementary Impact of Micro Distortions AutoresDokument35 SeitenThe Aggregate and Complementary Impact of Micro Distortions AutoresRodrigo GarayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cepal R.2172ictinla - GutierrezDokument24 SeitenCepal R.2172ictinla - GutierrezJorge BossioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring The Economic Value of Patent by OECDDokument42 SeitenMeasuring The Economic Value of Patent by OECD慧命Noch keine Bewertungen

- EXPORTS OF MANUFACTURES BY DEVELOPING COUNTRIES - EMERGING PATTERNS OF TRADE AND LOCATION Author(s) - SANJAYA LALL (1998)Dokument21 SeitenEXPORTS OF MANUFACTURES BY DEVELOPING COUNTRIES - EMERGING PATTERNS OF TRADE AND LOCATION Author(s) - SANJAYA LALL (1998)abhinavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global TradeDokument26 SeitenGlobal TradeCrystal TitarNoch keine Bewertungen

- CB BH200 2 Bluetooth HeadsetDokument31 SeitenCB BH200 2 Bluetooth HeadsetAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- ELTEK Valere Hybrid SolutionsDokument8 SeitenELTEK Valere Hybrid SolutionsAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Datasheet Rectiverter Integration Standalone 48 VDC 3kVA 1phDokument3 SeitenDatasheet Rectiverter Integration Standalone 48 VDC 3kVA 1phAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- File Transfer Guidelines: EBU - TECH 3318Dokument26 SeitenFile Transfer Guidelines: EBU - TECH 3318Anonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Battery PowerDokument32 SeitenBattery PowerAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pinouts Data Ethernet100BaseT4Crossover PinDokument2 SeitenPinouts Data Ethernet100BaseT4Crossover PinAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smartpack II UMDokument32 SeitenSmartpack II UMAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impulse Noise Protection For Multicarrier Communication SytemsDokument4 SeitenImpulse Noise Protection For Multicarrier Communication SytemsAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Set Top Box User Guide: Global Reach With A Local TouchDokument19 SeitenSet Top Box User Guide: Global Reach With A Local TouchAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Huawei AR Router FamilyDokument1 SeiteHuawei AR Router FamilyAnonymous jnG2gQEbHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jacques-Alain Miller Habeas-CorpusDokument7 SeitenJacques-Alain Miller Habeas-CorpusShigeo HayashiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Independent Nurse PractitionerDokument4 SeitenIndependent Nurse PractitionerVijith.V.kumar50% (2)

- International Forum On Engineering Education (IFEE 2010) Book of AbstractsDokument91 SeitenInternational Forum On Engineering Education (IFEE 2010) Book of AbstractsHarold TaylorNoch keine Bewertungen

- SED 1FIL-10 Panimulang Linggwistika (FIL 102)Dokument10 SeitenSED 1FIL-10 Panimulang Linggwistika (FIL 102)BUEN, WENCESLAO, JR. JASMINNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Invention of AdolescenceDokument3 SeitenThe Invention of AdolescenceJincy JoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bachelor of Nursing Second Entry PreparationDokument5 SeitenBachelor of Nursing Second Entry PreparationKennix Scofield KenNoch keine Bewertungen

- NGSS CA Framework: Transitional Kindergarten FrameworkDokument32 SeitenNGSS CA Framework: Transitional Kindergarten FrameworkStefanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mass Media EffectsDokument12 SeitenMass Media EffectsTedi0% (1)

- Thesis in Teaching Social StudiesDokument5 SeitenThesis in Teaching Social Studiesdwhchpga100% (2)

- IGCSE 2017 (Mar) Physics Paper 1.12 - Answer PDFDokument3 SeitenIGCSE 2017 (Mar) Physics Paper 1.12 - Answer PDFMaria ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jessica Brooks - Resume Nurs 419 1Dokument1 SeiteJessica Brooks - Resume Nurs 419 1api-469609100Noch keine Bewertungen

- HIEPs Mek-210819 PresentDokument46 SeitenHIEPs Mek-210819 Presentamirah74-1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tvl-Ict 11Dokument33 SeitenTvl-Ict 11Jubert Padilla100% (1)

- DEVELOPMENTAL DATA A. Havighurst's Theory of DevelopmentalDokument3 SeitenDEVELOPMENTAL DATA A. Havighurst's Theory of Developmentalnmaruquin17850% (1)

- Prospectus Aiims DM-MCH July 2016Dokument48 SeitenProspectus Aiims DM-MCH July 2016anoop61Noch keine Bewertungen

- Forensic ScienceDokument6 SeitenForensic SciencesvedanthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume Saima Zakir OomerDokument2 SeitenResume Saima Zakir OomerYasi HanifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employee Retention Relationship To Training and Development: A Compensation PerspectiveDokument7 SeitenEmployee Retention Relationship To Training and Development: A Compensation PerspectivefaisalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application Cell Form 2021-22Dokument11 SeitenApplication Cell Form 2021-22Aroush KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

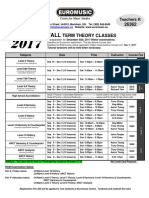

- Teachers #:: Centre For Music StudiesDokument2 SeitenTeachers #:: Centre For Music StudiesMegan YimNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of SchoolsDokument8 SeitenList of Schoolssarva842003Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1st Announcement KONKER PDPI 2019 PDFDokument16 Seiten1st Announcement KONKER PDPI 2019 PDFyonna anggrelinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Upside Down Art - MichelangeloDokument3 SeitenUpside Down Art - Michelangeloapi-374986286100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Kangaroo Mother Car PDFDokument15 SeitenLesson Plan Kangaroo Mother Car PDFhanishanandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eps 10 DoneDokument3 SeitenEps 10 DoneMharilyn E BatalliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tennis Australia 2012 2013Dokument80 SeitenTennis Australia 2012 2013pjantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nasruddin Hodja - A Master of The Negative WayDokument11 SeitenNasruddin Hodja - A Master of The Negative WaySeyedAmir AsghariNoch keine Bewertungen

- EE21-2 For MEDokument6 SeitenEE21-2 For MECJ GoradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coop Problem Solving Guide PDFDokument310 SeitenCoop Problem Solving Guide PDFgiyon0Noch keine Bewertungen

- Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade 4 Learning Area: English Quarter 3 Week No. 2 Date Covered: April 12-16, 2021Dokument4 SeitenWeekly Home Learning Plan Grade 4 Learning Area: English Quarter 3 Week No. 2 Date Covered: April 12-16, 2021Eman CastañedaNoch keine Bewertungen