Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Teenage Drinking and The Onset of Alcohol Dependence: A Cohort Study Over Seven Years

Hochgeladen von

Fati NovOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Teenage Drinking and The Onset of Alcohol Dependence: A Cohort Study Over Seven Years

Hochgeladen von

Fati NovCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKADDAddiction0965-2140 2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

99

Original Article

Alcohol disorders and adolescent alcohol consumption

Yvonne A. Bonomo

et al.

RESEARCH REPORT

Teenage drinking and the onset of alcohol dependence:

a cohort study over seven years

Yvonne A. Bonomo1, Glenn Bowes2, Carolyn Coffey1, John B. Carlin3 & George C. Patton1

1

Centre for Adolescent Health, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute and Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne,2 Department of Paediatrics,

University of Melbourne, Royal Childrens Hospital, Parkville, Melbourne and 3Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics Unit, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute

and Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne

Correspondence to:

Yvonne Bonomo

5462 Gertrude Street

Fitzroy 3065

Victoria

Australia

Tel: + 61 39814 8444

E-mail: ybonomo@bigpond.com

Submitted 28 November 2003;

initial review completed 9 January 2004;

final version accepted 6 May 2004

RESEARCH REPORT

ABSTRACT

Aim To determine whether adolescent alcohol use and/or other adolescent

health risk behaviour predisposes to alcohol dependence in young adulthood.

Design Seven-wave cohort study over 6 years.

Participant A community sample of almost two thousand individuals followed from ages 1415 to 2021 years.

Outcome measure Diagnostic and Statistical Manual volume IV (DSM-IV) alcohol dependence in participants aged 2021 years and drinking three or more

times a week.

Findings Approximately 90% of participants consumed alcohol by age

20 years, 4.7% fulfilling DSM-IV alcohol dependence criteria. Alcohol dependence in young adults was preceded by higher persisting teenage rates of frequent drinking [odds ratio (OR) 8.1, 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.2, 16],

binge drinking (OR 6.7, 95% CI 3.6, 12), alcohol-related injuries (OR 4.5 95%

CI 1.9, 11), intense drinking (OR 4.8, 95% CI 2.6, 8.7), high dose tobacco use

(OR 5.5, 95% CI 2.3, 13) and antisocial behaviour (OR 5.9, 95% CI 3.3, 11).

After adjustment for other teenage predictors frequent drinking (OR 3.1, 95%

CI 1.2, 7.7) and antisocial behaviour (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.2, 5.1) held persisting

independent associations with later alcohol dependence. There were no prospective associations found with emotional disturbance in adolescence.

Conclusion Teenage drinking patterns and other health risk behaviours in

adolescence predicted alcohol dependence in adulthood. Prevention and early

intervention initiatives to reduce longer-term alcohol-related harm therefore

need to address the factors, including alcohol supply, that influence teenage

consumption and in particular high-risk drinking patterns.

KEYWORDS Adolescence, alcohol, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence,

cannabis, depression, emotional problems, young adults.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol now features prominently in the social interaction of teenagers in many countries. Among Australian

teenagers, approximately two-thirds report that they are

recent drinkers and around one-third drink weekly [1].

Figures for binge drinking vary between countries, from

15% of young Australians [1] to one-third of students in

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

Denmark, Ireland, Poland and the United Kingdom [2].

The most common adverse consequences of such patterns of drinking in young people include the acute

physiological effects of excessive alcohol (blackouts,

hangovers, etc.) and behavioural effects (violence, unsafe

sexual intercourse) [3].

Also disturbing are the significant rates of alcohol

dependence found among young adults. Twelve-month

doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00846.x

Addiction, 99, 15201528

Alcohol disorders and adolescent alcohol consumption

prevalence rates for alcohol disorders are similar across

western countries estimated to be at least 5% for males

and 2% for females [46] and, contrary to the popular

impression that alcohol disorders are most prevalent

among adults aged in their mid-40s, their prevalence is

highest among young adults. This raises questions

about the benign view of teenage drinking as a phase

that will abate with maturity. Insight into this issue is

hampered by the lack of studies of appropriate design.

Cross-sectional research does not capture the variability in alcohol consumption characteristic of adolescence. Retrospective longitudinal studies are limited by

bias in the recall of drinking patterns during teen years.

Prospective studies that have been conducted such as

the Swedish conscript study commenced their follow-up

only in late adolescence/early adulthood and defined

their outcome measure as a diagnosis of alcoholism

requiring admission to psychiatric care [7]. The results

cannot therefore be extrapolated readily to the current

social context where alcohol consumption by young

people is occurring earlier [8] and more heavily, resulting in symptoms of alcohol dependence that do not

reach clinical services until much later (if at all). This

study used a large community-based sample of adolescents followed prospectively to adulthood to examine

which teenage patterns of drinking (and other health

risk behaviour) predict the development of Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual volume IV (DSM-IV) alcohol

dependence.

METHODS

Procedure and sample

Between August 1992 and December 1998 a seven-wave

cohort study of adolescent health was conducted in Victoria, Australia. The cohort was defined using a two-stage

procedure. At stage 1, 45 schools from a stratified frame

of government, catholic and independent schools (total

number of students 60 905) were selected randomly. At

stage 2, a single intact class from each participating

school was selected at random to constitute the wave 1

sample. To augment the cohort sample size yet avoid

excessive burden on schools, recruitment to the study

was spread over two different school years: when the

wave 1 sample had moved into year 10, a second class

from each participating school was selected at random.

One school from the initial cross-sectional survey was

unavailable for study, leaving a total of 44 schools. At the

time of sampling, 98% of Victorian school students were

still recorded as present in the education system [9]. Participants were reviewed biannually during the teens

(waves 16) with final follow-up at age 20/21 years

(wave 7).

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

1521

Adolescent phase: waves 16

Written parental consent for participation was sought at

entry of the students into the study. The students completed measures at intervals of 6 months between year 9

and year 12 (six waves). Laptops were used to administer

the questionnaire [10]. Subjects unavailable for followup at school were interviewed by telephone. A total of

1943 adolescents (96% of the intended sample) participated at least once during waves 16 with a gender ratio

(males: 48.6%) similar to that in Victorian schools at the

time of sampling [9].

Missing data: waves 16

Seventy per cent of the cohort completed five waves of

data collection. As recruitment into the cohort was

staged over the first two waves, 54% of observations were

not present in the first wave of data collection. Proportions for missing observations in subsequent waves were

11%, 13%, 16%, 19% and 21% for waves 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6,

respectively. Multiple imputation was used to handle this,

enabling summary measures to be defined for each participant in each of five completed data sets. Final results

were obtained by combining analyses from the five

imputed data sets (see below). Imputation was performed

using a multivariate mixed effects model [11].

Young adult survey (wave 7, 1998)

The young adult survey was carried out by telephone

using computer-assisted interviews. Mean age of wave 7

participants was 20.7 years (SD 0.5); 46.0% were male

(Fig. 1).

A total of 1601 young adults (82% of all cohort participants) were interviewed between April and December

1998. Three hundred and forty-two participants were

not interviewed at wave 7; 152 refused, 59 were located

but unable to be contacted, 129 were lost to follow-up

and two had died from natural causes.

Outcome measure: alcohol dependence in

young adulthood

The young adult survey incorporated the Composite

International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) to assess DSMIV alcohol dependence [1215] according to standard

DSM criteria. The CIDI is a structured diagnostic interview designed for use by non-clinical professionals and

has been demonstrated to be both reliable and cross-culturally valid [1215].

A pragmatic consideration in the conduct of a cohort

study is the maintenance of participant cooperation by

the minimization of avoidable responder fatigue. It was

Addiction, 99, 15201528

1522

Yvonne A. Bonomo et al.

1st sample

N1=1037

2nd sample

N2=995

wave 1

n1=898

(87%)

late 1992

wave 2

n2=1728

(85%)

early 1993

Total intended sample = N1+N2 = 2032

Total achieved sample = 1943 (96%)

wav 3

n3=1699

(84%)

late 1993

wave 4

n4=1629

(80%)

early 1994

wave 5

n5=1576

(78%)

late 1994

wave 6

n6=1530

(75%)

early 1995

ADOLESCENT PHASE

wave 7

n7=1601

(79%)

1998

YOUNG

ADULT

SURVEY

Figure 1 Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Study, 19921998

considered unlikely that a diagnosis of alcohol dependence was consistent with only occasional alcohol use,

given the DSM-IV description of substance dependence

as repeated (substance) self-administration. Consequently, the CIDI interview was administered only to

those participants who reported using alcohol at least

three times a week. Our outcome is therefore defined as

alcohol dependence in frequent alcohol users.

beer, mixed drinks, etc.) and amounts (e.g. glass, can,

etc.) consumed in the 7 days prior to the survey. Estimates of frequency of consumption and self-reported

alcohol dose were calculated from the responses,

enabling the following classifications: (1) frequent drinkers: defined as drinking on 3 or more days in previous

week; and (2) binge drinkers: defined as consuming 45 g

of ethanol or more (equivalent to 5 + standard drinks)

[16].

Background factors

Alcohol-related consequences

Demographic factors and parental alcohol and tobacco use

Demographic factors and parental alcohol and tobacco

use were included as indicators of socio-economic status

and of environmental exposure to substances, recognized

as risk factors for alcohol disorders. Demographic factors

included gender and country of birth. Participants were

also asked at each wave to report their parents marital

status (married, de facto, divorced, single or dead) and

their parents highest level of education (high school

not completed, high school completed, non-university

tertiary education, university education). Variables for

parental marital status classifying parental divorce or

separation by wave 6 and parental education were then

defined. Participant report of parental alcohol use was

categorized as none, drank most days or drank every

day. They were also asked whether their parents smoked

cigarettes never, occasionally, most days or every

day. Variables derived for parental alcohol and tobacco

use identified whether either parent drank or smoked

most days or every day.

Adolescent risk factors

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was assessed at each survey. Those

individuals who reported drinking alcohol were asked to

fill in a diary which recorded categories of alcohol (e.g.

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

There were three broad categories of alcohol-related consequences examined among the adolescents:

1 Intense drinking. Two items in the adolescent phase

surveys asked about intense drinking. The first item

related to drinking to a significantly altered conscious

state. Respondents were asked whether they had ever

consumed so much alcohol that they could not

remember the next day about events the night before.

The second item asked the adolescents if they had ever

found themselves unable to stop drinking.

2 Alcohol-related accidents or injuries. The adolescents

were asked: In the last 6 months have you had an

injury because of drinking: never, once, more than

once? They were then asked In the last 6 months have

you had an accident because of drinking: never, once,

more than once?

3 Alcohol-related sexual risk-taking. There were three

items that related to sexual risk-taking under the influence of alcohol in the adolescent survey. Participants

were asked: In the last 6 months, have you ever had

any of the following problems because of drinking?

Having sex with someone and later regretting it? Having sex without using a contraceptive? Having sex with

out using a condom?

Where two or more adverse outcomes of drinking

were reported, they were classified as being recurrent and

assessed as potential risk factors for subsequent alcohol

dependence.

Addiction, 99, 15201528

Alcohol disorders and adolescent alcohol consumption

1523

Tobacco use

Ethics approval

Tobacco use was assessed at each survey. Those who

reported that they were smokers were asked to keep a 7day retrospective smoking diary, in which the individual

reported the number of cigarettes smoked on each day

during the last week. The following groups were categorized: (i) occasional smokingin previous month, but

less than 6 days in the previous week; (ii) daily smokingon 67 days of previous week; and (iii) high dose

smokingdaily, with an average of 10 + cigarettes per

day.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Royal Childrens

Hospital Ethics Committee.

Cannabis use

Cannabis use was assessed by asking the adolescents at

each wave whether they had used marijuana. Those who

had were asked to report how often they had used it in the

previous six months. At least weekly use was defined as

frequent cannabis use.

Data analysis

Data analysis was undertaken using Stata 7 [23] and followed the method of Rubin [24] for creating valid inferences under the assumptions of the imputation model,

combining over separate analyses performed on each of

the imputed datasets. Software for facilitating these analyses was written in Stata [25].

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed on the binary outcome of alcohol

dependence. The Wald test was used to assess first order

interactions. All confidence intervals are based on the

95% level. Two-tailed P-values are reported.

RESULTS

Antisocial behaviour

Alcohol dependence in young adulthood (wave 7)

Antisocial behavior was assessed at each wave based on

10 items from the Self-Report Early Delinquency Scale

covering property damage, interpersonal violence and

theft in previous 6 months [17].

Psychological distress

Depression and anxiety were assessed using the revised

Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) [18,19], providing

data on the frequency and severity of 14 common psychiatric symptoms [20]. The total scores were dichotomized

at 11/12 reflecting a level appropriate for clinical intervention [18,21,22].

Peer alcohol use

Participants were asked how many of their friends drank

alcohol: none, some, most or dont know. A variable

was defined that classified participants who reported that

most of their friends drink alcohol.

Explanatory variables: waves 16

Measures of persistence at a defined level of intensity were

constructed: (i) the number of waves at which a condition

was reported was counted and classified into three levels:

zero, one wave (indicating experimentation), two to six

waves (indicating persisting exposure); and (ii) maximal

level of cigarette smoking reported during the six waves

was categorized into (none; less than daily; daily and less

than 10 cigarettes/day; daily and 10 or more cigarettes/

day).

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

Of the 1601 wave 7 young adults, 1374 consumed alcohol in the previous year and 124 reported drinking at

least three times a week. Sixty-eight (55% of participants

drinking three or more times a week) fulfilled DSM-IV

alcohol dependence criteria. They were more likely to be

male (OR 3.7, 95% CI 2.1, 6.5), have divorced parents

(OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0, 3.0) and to have at least one parent

who drank alcohol most days (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2, 3.2)

(Table 1). Ninety-six per cent (CI 93%, 98%) of these

adults had reported drinking during the adolescent phase

(waves 16).

Univariate associations between alcohol dependence in

frequent drinkers (wave 7) and adolescent exposures

(waves 16)

Frequent drinking and binge drinking in adolescent

waves 16 defined separate groups of individuals

(Table 2). Frequent drinkers in adulthood were assessed

for the frequency of adolescent factors and for crude associations with alcohol dependence (Table 3).

Persistence of drinking patterns and alcohol-related behaviour

Frequent drinking and binge drinking each showed

strong associations with alcohol dependence in young

adulthood. Recurrent reports increased odds for later

dependence at least sixfold (recurrent frequent drinking:

OR 8.1, 95% CI 4.2, 16; recurrent binge drinking: OR

6.7, 95% CI 3.6, 12). Alcohol dependence was also more

likely with persistent alcohol-related accidents and

Addiction, 99, 15201528

1524

Yvonne A. Bonomo et al.

Table 1 Association of background factors with alcohol dependence at the age of 20 years (n = 1601): odds ratios (OR) from univariate

logistic regression models.

Alcohol dependence at age 20 years

Background factor

OR

95% CI

Male

Parental divorce/separation by wave 6

Parental education

Tertiary

Completed secondary

Incomplete secondary

One or both parents drinks most days

One or both parents smokes most days

735

284

3.7

1.7

2.1, 6.5

1.0, 3.0

576

510

515

568

991

1

1.7

1.4

2.0

1.6

0.94, 3.2

0.77, 2.7

1.2, 3.2

0.94, 2.8

Table 2 Alcohol use from wave 17 in 1601 wave 7 participants. Figures are percentages (standard errors).

Wave of survey

Mean age (years)

Non-drinker

No drinking last week

Drank 1 or 2 days last week

Max < 45 g/day

Max > 45 g/day

Drank 3 or more days last week

Max < 45 g/day

Max > 45 g/day

14.9

57.7 (2.00)

28.6 (1.84)

15.5

46.1 (1.28)

32.0 (1.20)

15.9

35.4 (1.27)

37.7 (1.34)

16.4

27.9 (1.17)

42.0 (1.33)

16.8

31.6 (1.31)

36.2 (1.37)

17.4

17.9 (0.99)

46.9 (1.26)

20.7

14.0 (0.87)

29.3 (1.14)

5.7 (0.66)

5.6 (0.73)

9.6 (0.75)

8.6 (0.78)

11.7 (0.81)

10.6 (0.87)

11.0 (0.88)

14.7 (0.90)

10.9 (0.83)

16.9 (0.98)

10.9 (0.80)

18.8 (1.02)

12.2 (0.82)

30.1 (1.15)

0.8 (0.30)

1.6 (0.39)

0.8 (0.24)

2.8 (0.45)

1.3 (0.32)

3.3 (0.47)

0.8 (0.25)

3.6 (0.57)

0.4 (0.16)

4.1 (0.55)

0.7 (0.22)

4.7 (0.55)

2.4 (0.39)

11.9 (0.81)

injuries (OR 4.5, 95% CI 1.9, 11) and with intense drinking (OR 4.8, 95% CI 2.6, 8.7) but not with alcoholrelated sexual risk taking.

Psychiatric morbidity

No evidence of association with psychiatric morbidity

was found.

Drinking peers

Adolescents who persistently reported that most friends

drank were eightfold more likely to be alcohol-dependent

later (OR 8.1, 95% CI 2.5, 26).

Cigarette smoking

High dose (10 + cigarettes) daily smoking in adolescence

had fivefold increased odds of alcohol dependence (OR

5.5, 95% CI 2.3, 13).

Cannabis use, antisocial behaviour

Both cannabis use and antisocial behaviour were associated prospectively with alcohol dependence in young

adulthood. The odds increased with increasing frequency

of antisocial behaviour (OR for report at one wave: 2.7,

95% CI 1.3, 5.6; OR for report at multiple waves: 5.9,

95% CI 3.3, 11).

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

Independent associations between alcohol dependence in

frequent drinkers (wave 7) and adolescent exposures

(waves 16)

Multiple logistic regression was used to examine independent predictive associations between alcohol dependence

in young adulthood and adolescent measures and to

adjust for possible confounding (Table 4). An independent relationship between alcohol dependence in young

adulthood and frequent teenage drinking was demonstrated, the likelihood increasing with persistence of frequent drinking through adolescence (OR for frequent

drinking at one wave: 2.0, 95% CI 1.0, 4.3; OR for frequent drinking at multiple waves: 3.1, 95% CI 1.2, 7.7).

Adolescent antisocial behaviour was also associated

independently with alcohol dependence, with individuals

persistently reporting such behaviour being approximately 2.5 times more likely to be in the alcohol-dependent group in young adulthood (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.2,

Addiction, 99, 15201528

Alcohol disorders and adolescent alcohol consumption

1525

Table 3 Estimated frequency of time varying adolescent measures and their association with alcohol dependence in frequent alcohol users

at age 20 years (n = 1601): odds ratios (OR) from univariate logistic regression models.

Estimated frequency

Alcohol dependence at

age 20 years

Adolescent measure: waves 16

Category

95% CI

OR

Frequent drinking

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

Occasional

Daily, < 10 cigs/day

Daily, > 10 cigs/day

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

1344

169

88

900

298

403

1460

88

53

1450

97

55

1247

204

150

413

220

969

632

606

207

157

1415

80

106

1244

188

169

857

245

499

1313, 1374

142, 196

68, 108

858, 942

263, 333

367, 439

1438, 1483

70, 106

38, 67

1425, 1474

77, 117

40, 69

1213, 1281

177, 231

125, 176

377, 449

184, 255

927, 1011

578, 686

552, 660

180, 233

133, 181

1389, 1440

61, 99

86, 127

1206, 1282

155, 221

144, 194

808, 905

202, 288

462, 537

1

4.4

8.1

1

3.0

6.7

1

2.0

4.5

1

1.5

0.88

1

2.1

4.8

1

2.3

8.1

1

2.4

3.9

5.5

1

4.3

2.7

1

2.7

5.9

1

1.2

0.91

Binge drinking

Alcohol-related injuries or accidents: 2

or more behaviours

Alcohol-related sexual risk-taking: 2 or

more behaviours

Intense drinking: 2 or more behaviours

Most friends drink alcohol

Maximal tobacco smoking

Weekly or more frequent cannabis use

Antisocial behaviour: 2 or more

behaviours

Psychiatric morbidity CIS > 11

95% CI

2.4, 8.4

4.2, 16

1.4, 6.7

3.6, 12

0.8, 5.1

1.9, 11

0.6, 3.8

0.2, 3.7

1.0, 4.2

2.6, 8.7

0.4, 12

2.5, 26

1.0, 5.8

1.6, 9.7

2.3, 13

1.7, 10.5

1.2, 6.1

1.3, 5.6

3.3, 11

0.6, 2.8

0.5, 1.6

CIS, Clinical Interview Schedule.

5.1). No first order interaction effects between gender

and any explanatory variable were found.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that the clearest predictor of

alcohol dependence in young adults was regular recreational alcohol use in the teens. Regular drinking clustered with a range of health risk behaviours including

binge drinking, injuries and accidents under the

influence of alcohol, smoking in high dose and cannabis

use.

Although alcohol dependence has been accepted traditionally as occurring in young adulthood [26,27], the

strong association between frequent teen drinking and

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

alcohol dependence in adulthood may reflect an already

existent dependence syndrome in adolescence. Surveys

based on both general population and clinical samples

indicate that DSM alcohol disorders are evident at as

early as 1617 years of age [28]. While such data support

the concept that adolescents can experience alcohol

dependence the extrapolation to adolescents of DSM criteria developed for adults is problematic. The frequently

progressive nature of adult drinking problems and the

spectrum of chronic complications (such as liver, pancreatic and other gastrointestinal injury as well as neurological and cardiovascular injury) are observed far less

frequently in adolescents who abuse alcohol. DSM criteria for alcohol disorders also appear to have different

implications for adolescents compared to adults. For

instance, while tolerance is often considered to have high

Addiction, 99, 15201528

1526

Yvonne A. Bonomo et al.

Table 4 Predictive association of adolescent measures with alcohol dependence in frequent alohol users at age 20 years (n = 1601), adjusted

for sex, parental divorce/separation and parental alcohol use: odds ratios (OR) from multivariate logistic regression models.

Alcohol dependence at age 20 years

Adolescent measure: waves 16

Category

OR

Frequent drinking

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

Occasional

Daily, < 10 cigs/day

Daily, > 10 cigs/day

None

One wave

More than one wave

None

One wave

More than one wave

1

2.0

3.1

1

1.5

1.4

1

0.59

0.82

1

1.0

1.8

1

1.6

3.2

1

1.5

1.5

1.6

1

1.4

0.48

1

1.3

2.4

Binge drinking

Alcohol-related injuries or accidents: 2 or more behaviours

Intense drinking: 2 or more behaviours

Most friends drink alcohol

Maximal tobacco smoking

Weekly or more frequent cannabis use

Antisocial behaviour: 2 or more behaviours

specificity in alcohol-dependent adults, it appears to have

low specificity among problem drinking adolescents in

treatment [29]. DSM criteria also do not account for

interruptions to adolescent psychosocial development in

recurrent adolescent alcohol abuse.

If the association is not measurement-related, then a

process of kindling may explain frequent teen drinking

progressing to dependence. Cycles of regular exposure

increase tolerance to alcohol, which drive escalating consumption [27,30,31]. For some, constitutional predisposition to heavy intake making it difficult to moderate

drinking may play a role. For example, individuals with a

family history of alcohol abuse have described feeling less

intoxicated at high blood alcohol levels [3234]. Studies

of genetics suggest at least some heritability of vulnerability to alcoholism [35,36]. More broadly, there are

significant social influences that influence heavy

consumption of alcohol by young people today. These

include peer models and normative expectations about

alcohol which, in large part, are driven by such developments as the production of sweet and colourful alcoholic

beverages with tantalizing names as well as intensive

marketing of alcohol to young people portraying alcohol

consumption as fun and sexy through both traditional

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

95% CI

1.0, 4.3

1.2, 7.7

0.62, 3.6

0.61, 3.4

0.21, 1.7

0.27, 2.5

0.47, 2.1

0.82, 4.1

0.27, 9

0.94, 11

0.58, 3.8

0.55, 4.1

0.53, 4.7

0.51, 4.0

0.17, 1.4

0.58, 2.8

1.2, 5.1

and newer media (internet, SMS texts on mobile phones)

[37,38]. These social changes provide challenges in

defining what is the healthy norm for adolescent alcohol

consumption.

This study has a number of advantages, including

high participation rates and frequent prospective measures during the teens. Alcohol consumption and other

health risk behaviours in adolescence were recorded at 6monthly intervals, capturing some of the variability in

behaviour that is characteristic among adolescents. It

was also possible to examine adolescent patterns of drinking in detail. Apart from quantity and frequency of alcohol intake, adverse outcomes of adolescent problem

drinking were included in the analysis. The use of multiple imputation enabled bias introduced by missing data in

the course of the study to be addressed. This method is

valid under the assumption that the probability that a

participant is missing a wave can be predicted from data

observed at other waves (missing at random), and even

under some departure from this assumption is likely to

produce less biased results than complete-case analyses

[39]. Potential selection bias at the inception of the study

is likely to have been minimal because of high school

retention rates, and there was high ascertainment in the

Addiction, 99, 15201528

Alcohol disorders and adolescent alcohol consumption

study with 96% of the sampling frame having participated at least once.

As alcohol consumption among young people

increases, evidence is emerging for its potential longerterm impact. At present, there is marked ambivalence

within the community regarding teenage drinking and

what constitutes a safe level of alcohol consumption. The

traditional or conservative opinion is that young people

should not consume alcohol until at least age 18 years

because of continuing neurological, particularly cerebral, development [40,41]. The alternative view is that

alcohol consumption by teenagers is not only acceptable

but of little concern, because it is better than illicit drug

use and that periods of blackouts and other complications

of alcohol use among young people are merely part of the

rite of passage to adulthood [42]. This ambivalence

results in a failure to mount a robust defence against the

increasingly assertive marketing of alcohol products to

young people. In addition, prevention and early intervention initiatives to reduce longer-term alcohol-related

harm need to broaden their focus to include adolescents,

in particular uptake of alcohol with other substances and

high-risk drinking patterns.

References

1 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2002)

2001 National Drug Strategy Household Survey. First results.

Report no. AIHW cat. no. PHE. 35. Canberra: Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare.

2 ESPAD99 (2000) Summary of the 1999 Findings. Available

at: http://www.hnnsweden.com.

3 Shanahan, P. & Hewitt, N. (1999) Developmental Research for

a National Alcohol Campaign. Canberra: Commonwealth of

Australia.

4 Hall, W., Teesson, M., Lynskey, M. & Degenhardt, L.

(1998) The Prevalence in the Past Year of Substance Use and

ICD-10 Substance Use Disorders in Australian Adults. Findings from the National Survey of Mental Health and WellBeing, Report no. 63. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol

Research Centre.

5 Kessler, R. C., Crum, R. M., Warner, L. A., Nelson, C. B.,

Schulenberg, J. & Anthony, J. C. (1997) Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with

other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 313321.

6 DeWit, D. J., Adlaf, E. M., Offord, D. R. & Ogborne, A. C.

(2000) Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry,

157, 745750.

7 Andreasson, S., Allebeck, P. & Brandt, L. (1993) Predictors

of alcoholism in young Swedish men. American Journal of

Public Health, 83, 845850.

8 Hill, D. J., White, V. M., Williams, R. M. & Gardner, G. J.

(1993,) Tobacco and alcohol use among Australian secondary school students in 1990. Medical Journal of Australia,158, 228234.

9 Australian Bureau of Statistics (1993) Australias Young People. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

1527

10 Paperny, D. M., Aono, J. Y., Lehman, R. M., Hammar, S. L. &

Risser, J. (1990) Computer-assisted detection and intervention in adolescent high-risk health behaviours. Journal of

Paediatrics, 116, 456462.

11 Schafer, J. L. & Yucel, R. M. (2002) Computational strategies

for multivariate linear mixed-effects models with missing

values. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statisitics , 11,

437457.

12 Room, R., Janca, A., Bennett, L. A., Schmidt, L. & Sartorius,

N. (1996) WHO cross-cultural applicability research on diagnosis and assessment of substance use disorders: an overview

of methods and selected results. Addiction, 91, 199220.

13 Cottler, L. B., Robins, L. N., Grant, B. F., Blaine, J., Towle, L.

H., Wittchen, H. & Sartorius, N. (1991) The CIDIcore substance abuse and dependence questions. Cross-cultural and

nosological issues. British Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 653

658.

14 Wittchen, H., Robins, L. N., Cottler, L. B., Sartorius, N.,

Burke, J. D. & Reiger, D. (1991) Cross-cultural feasibility,

reliability and sources of variance of the composite international diagnostic interview. British Journal of Psychiatry,

159, 645653.

15 Cottler, L. B., Robins, L. N. & Helzer, J. E. (1989) The reliability of the CIDI-SAM: a comprehensive substance abuse interview. British Journal of Addiction, 84, 801814.

16 National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC)

(1987) Is There a Safe Level of Daily Consumption of Alcohol for

Men and Women? Recommendations Regarding Responsible

Drinking Behaviour. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

17 Moffitt, T. E. & Silva, P. A. (1988) Self-reported delinquency:

results from an instrument for New Zealand. Australian and

New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 21, 227240.

18 Lewis, G. & Pelosi, A. J. (1992) The Manual of the Revised

Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R). London: Institute of

Psychiatry.

19 Mann, A. H., Wakeling, A., Wood, K., Monck, E., Dobbs, R. &

Szmukler, G. (1983) Screening for abnormal eating attitudes and psychiatric morbidity in an unselected population

of 15-year-old schoolgirls. Psychological Medicine, 13, 573

580.

20 Bebbington, P. E., Dunn, G., Jenkins, R., Lewis, G., Brugha,

T. S. & Farrell, M. (1998) The influence of age and sex on the

prevalence of depressive conditions: report from the

National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. Psychological Medicine, 28, 919.

21 Lewis, V., Pelosi, A. J., Glover, E., Wilkinson, G., Stansfeld, S.

A., Willliams, P. & Shepherd, M. (1988) The development of

a computerised assessment for minor psychiatric disorder.

Psychological Medicine, 18, 737745.

22 Harrington, R., Fudge, H., Rutter, M., Pickles, A. & Hill, J.

(1991) Adult outcomes of childhood and adolescent

depression. II. Links with antisocial disorders. Journal of

the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry ,

30, 434439.

23 Stata Corporation (2001) STATA_7. USA: Stata Corporation.

24 Rubin, D. B. (1987) Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in

Surveys. New York: Wiley.

25 Carlin, J. B., Li, N., Greenwood, P. & Coffey, C. (2003) Tools

for analyzing multiple imputed datasets. The Stata Journal, 3,

120.

26 Cahalan, D. (1976) Problem Drinkers. A National Survey, 2nd

edn. San Francisco/London: Jossey-Bass, Inc. Publishers.

27 Fillmore, K. M. (1987) Prevalence, incidence and chronicity

Addiction, 99, 15201528

1528

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

Yvonne A. Bonomo et al.

of drinking patterns and problems among men as a function

of age: a longitudinal and cohort analysis. British Journal of

Addiction, 82, 7783.

Nelson, C. B. & Wittchen, H. (1998) DSM-IV alcohol disorders in a general population sample of adolescents and

young adults. Addiction, 93, 10651077.

Martin, C. S., Kaczynski, N. A., Maisto, S. A., Bukstein, O. M.

& Moss, H. B. (1995) Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and

dependence symptoms in adolescent drinkers. Journal of

Studies on Alcohol, 56, 672680.

Fillmore, K. M. (1975) Relationships between specific drinking problems in early adulthood and middle age. An exploratory 20-year follow-up study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol,

36, 882907.

Vaillant, G. E. (1983) The Natural History of Alcoholism,

1st edn. Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University

Press.

Schuckit, M. A. (1980) Self-rating of alcohol intoxication by

young men with and without family histories of alcoholism.

Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 41, 242249.

Schuckit, M. (1984) Subjective responses to alcohol in sons

of alcoholics and control subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41, 879884.

Schuckit, M. A. (1985) Ethanol-induced changes in body

sway in men at high alcoholism risk. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 375379.

2004 Society for the Study of Addiction

35 Kendler, K. S., Neale, M. C., Heath, A. C., Kessler, R. C. & Eaves,

L. J. (1994) A twin-family study of alcoholism in women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 707715.

36 Rutter, M., Macdonald, H., Le Couteur, A., Harrington, R.,

Bolton, P. & Bailey, A. (1990) Genetic factors in child psychiatric disorders. II. Empirical findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 31, 3983.

37 Edwards, G., Anderson, P., Babor, T. F., Casswell, S., Ferrence, R., Giesbrecht, N. et al. (1994) Alcohol Policy and the

Public Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

38 Casswell, S. & Zhang, J. (1998) Impact of liking for advertising and brand allegiance on drinking and alcohol-related

aggression: a longitudinal study. Addiction, 93, 12091217.

39 Little, R. J. A. & Rubin, D. B. (2002) Statistical Analysis with

Missing Data, 2nd edn. New York: Wiley.

40 Brown, S., Tapert, S. F., Granholm, E. & Delis, D. C. (2000)

Neurocognitive functioning of adolescents. Effects of protracted alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental

Research, 24, 164171.

41 Spear, L. P. (2002) The adolescent brain and the college

drinker: biological basis of propensity to use and misuse

alcohol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement, 14, 7181.

42 Shanahan, P., Wilkins, M. & Hurt, N. (2002) A Study of Attitudes and Behaviours of Drinkers at Risk. Research report.

Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Department of Health

and Ageing.

Addiction, 99, 15201528

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Trends in Exposure To Secondhand Smoke Among Adolescents in China From 2013-2014 To 2019: Two Repeated National Cross-Sectional SurveysDokument13 SeitenTrends in Exposure To Secondhand Smoke Among Adolescents in China From 2013-2014 To 2019: Two Repeated National Cross-Sectional SurveysAli HNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agr080 PDFDokument8 SeitenAgr080 PDFDurga BalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Analysis of University Students Who Are SmokersDokument6 SeitenAn Analysis of University Students Who Are SmokersAngelo BacalsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Drug Abuse Prevention StrategiesDokument90 SeitenImpact of Drug Abuse Prevention StrategiesLi An Rill100% (1)

- The Prevalence and Associated Factors of Alcohol Use During Pregnancy Among Pregnant Women in The Buea Town Health CenterDokument70 SeitenThe Prevalence and Associated Factors of Alcohol Use During Pregnancy Among Pregnant Women in The Buea Town Health CenterFavour ChukwuelesieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, KarnatakaDokument13 SeitenRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, KarnatakaAmit TamboliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect of Substance Abuse Among Youths of Ugwan Rana - Madam SusieDokument68 SeitenThe Effect of Substance Abuse Among Youths of Ugwan Rana - Madam SusieDemsy Audu100% (1)

- 071-005 Factor AssociatedDokument5 Seiten071-005 Factor AssociatedAzlisonGuilaboBawangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Chapter 1 5Dokument14 SeitenThesis Chapter 1 5Felicity Mae Dayon BaguioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inteligencia y DrogasDokument4 SeitenInteligencia y DrogasCorcu EraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Depression Amongst Nigerian University SDokument5 SeitenDepression Amongst Nigerian University SLucas ViniciusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mhealth Smoking Cessation Intervention Among High School Students 3month Primary Outcome Findings From A Randomized Controlled TrialDokument11 SeitenMhealth Smoking Cessation Intervention Among High School Students 3month Primary Outcome Findings From A Randomized Controlled TrialrawaidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Kebugaran JasmaniDokument10 SeitenJurnal Kebugaran JasmaniAbil 00Noch keine Bewertungen

- Needs AssessmentDokument24 SeitenNeeds Assessmentapi-295271022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ijerph 06 01254Dokument14 SeitenIjerph 06 01254r4adenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voice Nodul JournalDokument9 SeitenVoice Nodul JournalSoni SulistomoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation of Reasons For Excessive Alcohol Use and The Effects On Students of Kampala International University Western CampusDokument13 SeitenEvaluation of Reasons For Excessive Alcohol Use and The Effects On Students of Kampala International University Western CampusKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNoch keine Bewertungen

- LifestyleDokument55 SeitenLifestyleiyangtejanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Keywords:-Alcohol Drinking Health Beahvior COVID-19Dokument7 SeitenKeywords:-Alcohol Drinking Health Beahvior COVID-19International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Substance Abuse Prevention 4781Dokument20 SeitenA Study On Substance Abuse Prevention 4781sesethujunuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Australia UniversidadDokument8 SeitenAustralia UniversidadAndrésFelipeMaldonadoGiratáNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDokument5 SeitenThe Problem and Its BackgroundKaye Jelai De LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- LiteratureDokument6 SeitenLiteratureReshel Mae PontoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive SummaryDokument28 SeitenExecutive Summaryengidayehu melakuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tobacco Use and Oral Health Status Among Adolescents in An Urban Slum, GurugramDokument5 SeitenTobacco Use and Oral Health Status Among Adolescents in An Urban Slum, GurugrampriyankaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER 1 FinalDokument5 SeitenCHAPTER 1 FinalMEKA ELA MALINAONoch keine Bewertungen

- Alcohol Use in Adolescence: Identifying Harms Related To Teenager's Alcohol DrinkingDokument11 SeitenAlcohol Use in Adolescence: Identifying Harms Related To Teenager's Alcohol DrinkingsindyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Influences Encouraging Alcohol Use Among Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery Students at Kampala International University, Western Campus, Ishaka Bushenyi, Western UgandaDokument13 SeitenInfluences Encouraging Alcohol Use Among Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery Students at Kampala International University, Western Campus, Ishaka Bushenyi, Western UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smoking Prevalence and Awareness About Lobacco Related Diseases Among Medical Students of Ziauddin Medical UniversityDokument6 SeitenSmoking Prevalence and Awareness About Lobacco Related Diseases Among Medical Students of Ziauddin Medical Universityimran82aliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alcohol and Cannabis Intake in Nursing StudentsDokument14 SeitenAlcohol and Cannabis Intake in Nursing StudentsPaola PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 Oa Prevalence and Causalities ofDokument5 Seiten03 Oa Prevalence and Causalities ofMG's Fhya Part IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Examining The Prevalence and Rise Factors of Cigarette Smoking Chap 2Dokument9 SeitenExamining The Prevalence and Rise Factors of Cigarette Smoking Chap 2Gcs GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Health Education On Cigarette Smoking Habits of Young Adults in Tertiary Institutions in A Northern Nigerian StateDokument13 SeitenEffects of Health Education On Cigarette Smoking Habits of Young Adults in Tertiary Institutions in A Northern Nigerian StateGaoudam NatarajanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alcohol Use Highschool Predicting CollegeDokument22 SeitenAlcohol Use Highschool Predicting CollegeNoli BayaisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Screening for cannabis abuse among youth with the CASTDokument11 SeitenScreening for cannabis abuse among youth with the CASTCristina SencalNoch keine Bewertungen

- RM Intro on GYTSDokument5 SeitenRM Intro on GYTSdeepakNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 SabiaEtAl ArchivesDokument9 Seiten2012 SabiaEtAl ArchivesKrusssNoch keine Bewertungen

- Substance Use Among University Students and AffectDokument16 SeitenSubstance Use Among University Students and AffectchadiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- J Epidemiol Community HealthDokument10 SeitenJ Epidemiol Community HealthFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cancer in Working-Age Is Not Associated With Childhood AdversitiesDokument6 SeitenCancer in Working-Age Is Not Associated With Childhood AdversitiesBadger6Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adolescent Smoking Knowledge, Attitudes, and BehaviorsDokument9 SeitenAdolescent Smoking Knowledge, Attitudes, and BehaviorsSarah Ong SiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seminar 2 QuestionsDokument10 SeitenSeminar 2 QuestionsWafaa AdamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Version Scholarly PaperDokument10 SeitenFinal Version Scholarly Paperapi-337713711Noch keine Bewertungen

- Alcohol ConsumptionDokument7 SeitenAlcohol ConsumptionAbel seyfemichaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Try and Try Again: Qualitative Insights Into Adolescent Smoking Experimentation and Notions of AddictionDokument8 SeitenTry and Try Again: Qualitative Insights Into Adolescent Smoking Experimentation and Notions of AddictionChanelle Honey VicedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greehilletal Adolescenteciguse FinalacceptedversionDokument30 SeitenGreehilletal Adolescenteciguse FinalacceptedversionlydNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem StatementDokument8 SeitenProblem Statementsp2056251Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Effects of Cigarette Smoking Among AdolescentsDokument6 SeitenThe Effects of Cigarette Smoking Among Adolescentssumi sumiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Proposal Group CDokument11 SeitenFinal Proposal Group CJimmy Matsons MatovuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trade Marketing 1Dokument10 SeitenTrade Marketing 1IvanBučevićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cigarette Smoking Among Adolescents in Northwest Ohio: Correlates of Prevalence and Age at OnsetDokument12 SeitenCigarette Smoking Among Adolescents in Northwest Ohio: Correlates of Prevalence and Age at OnsetAnonymous eTzODC5WBNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Prevalence of Smoking, Determinants and Chance of Psychological Problems Among Smokers in An Urban Community Housing Project in MalaysiaDokument9 SeitenThe Prevalence of Smoking, Determinants and Chance of Psychological Problems Among Smokers in An Urban Community Housing Project in Malaysialailatul husnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab 8 Allen - Perception of AlcoholDokument7 SeitenLab 8 Allen - Perception of Alcoholapi-583318017Noch keine Bewertungen

- Interpersonal Violence and Mental Health: New Findings and Paradigms For Enduring ProblemsDokument4 SeitenInterpersonal Violence and Mental Health: New Findings and Paradigms For Enduring ProblemsDewi NofiantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Iv Drug Users Presenting To A Tertiary Care Treatment CentreDokument5 SeitenSociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Iv Drug Users Presenting To A Tertiary Care Treatment CentremominamalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal B.ing 1Dokument7 SeitenJurnal B.ing 1Abangnya Dea AmandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of Factors Associated With Alcohol Abuse Among Youth Aged (15-25) Years in Acana-Taa Village, Aloi Sub-County, Alebtong DistrictDokument7 SeitenAssessment of Factors Associated With Alcohol Abuse Among Youth Aged (15-25) Years in Acana-Taa Village, Aloi Sub-County, Alebtong DistrictKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNoch keine Bewertungen

- Influence of Peer Domain Factors On Substance Use Among Female Students at The Nairobi and Thika Campuses of KMTCDokument16 SeitenInfluence of Peer Domain Factors On Substance Use Among Female Students at The Nairobi and Thika Campuses of KMTCEditor IjasreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Choices and Consequences: What to Do When a Teenager Uses Alcohol/DrugsVon EverandChoices and Consequences: What to Do When a Teenager Uses Alcohol/DrugsBewertung: 1 von 5 Sternen1/5 (1)

- It Is Possible!: PRINCIPLES OF MENTORING YOUNG & EMERGING ADULTS, #1Von EverandIt Is Possible!: PRINCIPLES OF MENTORING YOUNG & EMERGING ADULTS, #1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adolescent Impulsivity Phenotypes Characterized by Distinct Brain NetworksDokument8 SeitenAdolescent Impulsivity Phenotypes Characterized by Distinct Brain NetworksFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Altered Impulse Control in Alcohol Dependence - Neural Measures of Stop Signal Performance.Dokument11 SeitenAltered Impulse Control in Alcohol Dependence - Neural Measures of Stop Signal Performance.Fati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Immature Frontal Lobe Contributions To Cognitive Control in Children - Evidence From FMRIDokument11 SeitenImmature Frontal Lobe Contributions To Cognitive Control in Children - Evidence From FMRIFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alcohol Cues Increase Cognitive Impulsivity in Individuals With AlcoholismDokument8 SeitenAlcohol Cues Increase Cognitive Impulsivity in Individuals With AlcoholismFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- J Epidemiol Community HealthDokument10 SeitenJ Epidemiol Community HealthFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stop-Signal Reaction-Time Task Performance - Role of Prefrontal Cortex and Subthalamic NucleusDokument11 SeitenStop-Signal Reaction-Time Task Performance - Role of Prefrontal Cortex and Subthalamic NucleusFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maturation of Brain Function Associated With Response InhibitionDokument8 SeitenMaturation of Brain Function Associated With Response InhibitionhandpamNoch keine Bewertungen

- An FMRI Study of Response Inhibition in Youths With A Family History of AlcoholismDokument4 SeitenAn FMRI Study of Response Inhibition in Youths With A Family History of AlcoholismFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Immature Frontal Lobe Contributions To Cognitive Control in Children - Evidence From FMRIDokument11 SeitenImmature Frontal Lobe Contributions To Cognitive Control in Children - Evidence From FMRIFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cortical Gray Matter in Attention-Deficit-hyperactivity Disorder - A Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging StudyDokument12 SeitenCortical Gray Matter in Attention-Deficit-hyperactivity Disorder - A Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging StudyFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- BlazquezDokument10 SeitenBlazquezFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0028393209001596 MainDokument11 Seiten1 s2.0 S0028393209001596 MainFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Binge DinkingDokument36 SeitenBinge DinkingFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lopez HernandezDokument6 SeitenLopez HernandezFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- J Epidemiol Community HealthDokument10 SeitenJ Epidemiol Community HealthFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Funcionamiento Neuropsicológico en Jóvenes Con TBDokument7 SeitenFuncionamiento Neuropsicológico en Jóvenes Con TBFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Lenguaje y Los Trastornos Del NeurodesarrolloDokument7 SeitenEl Lenguaje y Los Trastornos Del NeurodesarrolloDany MenaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 188Dokument10 Seiten188Fati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ffee en TB Pediátrico y Comorbilidad Con TdahDokument18 SeitenFfee en TB Pediátrico y Comorbilidad Con TdahFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5Dokument11 Seiten5Fati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Visual P300s in Long-Term Abstinent AlcoholicsDokument16 SeitenVisual P300s in Long-Term Abstinent AlcoholicsFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Binge DinkingDokument36 SeitenBinge DinkingFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Binge DrinkingDokument9 SeitenBinge DrinkingFati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emocion Negativa Deteriora MT en Pacientes Pedáitrcos Con TB Tipo 1Dokument17 SeitenEmocion Negativa Deteriora MT en Pacientes Pedáitrcos Con TB Tipo 1Fati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Do Les C Deficit AtencDokument11 SeitenA Do Les C Deficit AtencRaul Hernandez HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tops and Boksem, 2011Dokument14 SeitenTops and Boksem, 2011Fati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- TDAH, Trastorno Por Déficit de Atención Con Hiperactividad en Adultos: Caracterización Clínica y TerapéuticaDokument7 SeitenTDAH, Trastorno Por Déficit de Atención Con Hiperactividad en Adultos: Caracterización Clínica y Terapéuticainfo-TEA50% (2)

- Levy and Wagner, 2011Dokument23 SeitenLevy and Wagner, 2011Fati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Missoner, Et Al 2006Dokument10 SeitenMissoner, Et Al 2006Fati NovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inglés 12, Primera ParteDokument3 SeitenInglés 12, Primera ParteVerónica VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Statement On Minimum Drinking AgeDokument8 SeitenThesis Statement On Minimum Drinking Agevxjtklxff100% (2)

- Alcohol AbuseDokument14 SeitenAlcohol AbuseAbdul QuyyumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grades 12 Philippine politics youth programsDokument8 SeitenGrades 12 Philippine politics youth programsMark Nel Venus100% (1)

- Alcohol in Our Lives: Curbing The Harm, 2010Dokument587 SeitenAlcohol in Our Lives: Curbing The Harm, 2010Stuff NewsroomNoch keine Bewertungen

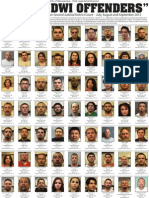

- Guilty DWI Offenders - August-September 2012Dokument2 SeitenGuilty DWI Offenders - August-September 2012Albuquerque JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of Alcoholics AnonymousDokument95 SeitenThe History of Alcoholics AnonymousDawn Farm100% (9)

- ThesisDokument40 SeitenThesisPiaRuela100% (2)

- IELTS Reading Matching Sentence EndingsDokument3 SeitenIELTS Reading Matching Sentence EndingsVân Anh NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dwidec 2009 Jan 2010Dokument2 SeitenDwidec 2009 Jan 2010Albuquerque JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sap PPT 2016-17Dokument11 SeitenSap PPT 2016-17aarushiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jake Seholm - DWI GogglesDokument2 SeitenJake Seholm - DWI GogglesBenile DestructionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Directions: in This Activity, You Are Tasked To Read The List of Words orDokument10 SeitenDirections: in This Activity, You Are Tasked To Read The List of Words orZarah Joyce Segovia100% (1)

- Influence of Social Capital On HealthDokument11 SeitenInfluence of Social Capital On HealthHobi's Important BusinesseuNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAST TestDokument5 SeitenMAST TestEnkelBulicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug and Alcohol Education ApproachesDokument15 SeitenDrug and Alcohol Education ApproachesJoan RiparipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Health Nursing Care PlanDokument4 SeitenCommunity Health Nursing Care Plankate russelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 6: Risk Assessment OverviewDokument45 SeitenModule 6: Risk Assessment OverviewHost MomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature ReviewDokument5 SeitenLiterature ReviewJohn C JohnNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Needs-Based Method For Estimating The Behavioral Health PDFDokument13 SeitenA Needs-Based Method For Estimating The Behavioral Health PDFaprilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk Child Assessment ChecklistDokument7 SeitenRisk Child Assessment ChecklistAyaBasilioNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER I The Problem Background of TheDokument43 SeitenCHAPTER I The Problem Background of TheHokage PrinceNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAGE Questionnaire For Alcohol MisuseDokument10 SeitenCAGE Questionnaire For Alcohol MisuseJeremy BergerNoch keine Bewertungen

- MULVEY ET AL Substance Use and Delinquent Behavior Among Serious Adolescent OffendersDokument16 SeitenMULVEY ET AL Substance Use and Delinquent Behavior Among Serious Adolescent OffendersFrancisco EstradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence and Correlates of Alcohol and Cannabis Use Disorders in the USDokument8 SeitenPrevalence and Correlates of Alcohol and Cannabis Use Disorders in the USFadil MuhammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Synopsis of AADokument43 SeitenA Synopsis of AAImNoRocketSurgeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 3 PR1Dokument33 SeitenGroup 3 PR1maica golimlimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4th Quarter HEALTH 8Dokument45 Seiten4th Quarter HEALTH 8Maria AiceyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociocultural FactorsDokument6 SeitenSociocultural FactorsjainchanchalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analytical EssayDokument5 SeitenAnalytical Essayapi-584599422Noch keine Bewertungen