Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Bank Note Case (R.G. Hawtrey)

Hochgeladen von

Neeraj MandaiyaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Bank Note Case (R.G. Hawtrey)

Hochgeladen von

Neeraj MandaiyaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Portuguese Bank Notes Case

Author(s): R. G. Hawtrey

Source: The Economic Journal, Vol. 42, No. 167 (Sep., 1932), pp. 391-398

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Royal Economic Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2224021 .

Accessed: 06/12/2014 12:37

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and Royal Economic Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Economic Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE PORTUGUESE

BANK NOTES CASE

THE history of swindles has been enriched in recent years by

several sensational examples, but by none more notable than that

which led to the case, Banco de Portugal v. Waterlow and Sons,

Ltd., decided by the House of Lords on the 28th April, 1932.

Messrs. Waterlow, the well-known printers of bank notes,

were the victims of a peculiarly audacious conspiracy. They

held a contract for printing notes for the Bank of Portugal,

and they were induced to produce notes, which were in all technical

respects apparently genuine, to the value of about ?3,000,000, for

a gang of forgers. Before the fraud was discovered, notes to the

amount of over ?1,000,000 had actually been put into circulation

by the conspirators, and Messrs. Waterlow had in the end to pay

damages to the amount of ?610,000, being the net loss suffered

by the Bank after setting off the assets recovered from the conspirators. The conspirators included the Portuguese Minister

at The Hague and the diplomatic representative of a South

American State. The negotiations with Messrs. Waterlow were

carried on through a Dutchman named Marang, who from time

to time produced forged letters and documents purporting to

convey the authority of the Bank of Portugal for what was to be

done.

The story put forward was that a loan was to be made to the

Portuguese Colony of Angola by a syndicate which was to have

the privilege of issuing notes in Angola. Inquiries which would

have exposed the fraud at once were guarded against by representing the whole business as extremely secret, on the ground that

it was opposed by some of the directors of the Bank of Portugal,

and that the Banco Ultramarino, which already issued notes in

the Colonies, would raise objection if the project were known.

How were the notes to be numbered ? If they were given

numbers not recorded at the Bank of Portugal as ever having

been issued, the officials of the Bank could hardly fail to discover

them immediately.

Instructions were given to Waterlows that

the numbers were to be duplicates of those on the last batch of

notes genuinely ordered by the Bank of Portugal. That was

arranged without arousing the suspicions of Messrs. Waterlow,

D D2

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

392

THE ECONOMIC JOURNAL

[SEPT.

but it involved the risk of notes with duplicate numbers being

seen and the fact of forgery being thereby established.

The printing of the notes began early in 1925. They were

all of the denomination of 500 escudos, or about ?5. The first

consignment, delivered in February and March 1925, consisted of

200,000 notes, and the second, delivered from August to November

1925, of 380,000. The two together represented a value of

290,000,000 escudos.

The principal difficulty in the way of forgers of currency

and false coiners has always been the introduction of their product

into circulation. The conspirators surmounted this obstacle

by founding a new bank, the Banco Angola e Metropole, with

head office at Oporto. That required the permission of the

Minister of Finance, and at first there was a hitch on account of

the unsatisfactory reputation of some of the promoters. But

some apparently respectable names were added, and on the

25th June, 1925, permission was granted, and the bank was duly

constituted.

The appearance of unusual quantities of new 500-escudo

notes presently awakened a certain amount of suspicion. But

the notes of course were to all appearance perfectly genuine,

even according to expert tests, and at first the suspicions were

met with reassuring denials. The circumstance that led to

discovery was that the packets of new notes received from the

Banco Angola e Metropole by a jeweller at Oporto, who bought

foreign exchange on behalf of the bank, differed from those

ordinarily received from the Bank of Portugal in that they were

not arranged in consecutive numerical order. An Oporto bank

cashier, who was employed in his spare time by the jeweller,

noticed this, and communicated his suspicions to the banker for

whom he worked and the latter informed the Bank of Portugal.

The cashier had also observed that the pages in the account

book on which the transactions in the suspicious notes were

entered were always torn out.

The shuffling of the notes out of numerical order was, no

doubt, an essential precaution to make the discovery of duplicate

numbers less likely, but it remained itself a cause of suspicion.

In fact, combined with the torn account book, it was regarded

as sufficient ground for arresting the manager of the Banco

Angola e Metropole the next day, the 5th December, 1925, and

f6r conducting an investigation of the premises.

Bundles of new notes were found, some in numerical order

and some rearranged. Comparison with the genuine notes at

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1932]

TITE PORTUGUESE BANK NOTES CASE

393

the Oporto Branch of the Bank of Portugal revealed four cases

of duplicate notes. The fact of forgery was proved, but its

extent was still unknown.

The Bank of Portugal took prompt action. The forged notes

were all 500-escudo notes, with a portrait of Vasco da Gama in

the design. A notice was issued on Monday the 7th December,

calling in all the notes of that denomination and design, and offering in exchange other notes not open to suspicion. The Government

sanctioned the exchange being made up to the 26th December,

and by that date very nearly all the suspect notes, both genuine

and forged, had been withdrawn.

Among the notes withdrawn, 135,318, with a face value of

67,659,000 escudos, were definitely proved to be forged by certain

small distinctive marks which showed that they had been printed

from plates which had never been used for genuine notes at all.

Expert scrutiny subsequently found means of distinguishing even

those which had been printed from the same plates as genuine

notes, and the total of forged notes withdrawn was placed at

209,718 with a face value of 104,859,000 escudos, or ?1,092,281,

at the rate of 96 to the ?1. The number seized without ever

getting into circulation was 363,602, so that 6,680 remained

unaccounted for.

The Bank of Portugal sued Messrs. Waterlow for damages in

respect of the redemption of the forged notes. The courts had

no difficulty in deciding that Messrs. Waterlow were liable.

They had committed a breach of an implied term of their contract

and it was not even necessary to prove negligence. But when

it came to determining the amount of the damages, doubts were

evinced which were mainly connected with the special position

of a central bank of issue.

In the first place, was the Bank justified in honouring the forged

notes at all? All the judges agreed that, so long as the Bank

had no means of distinguishing the forged notes from the genuine,

they had no alternative but to honour both. It was contended

on behalf of Messrs. Waterlow that the Bank could readily have

obtained from the firm within a few days information enabling

them to distinguish all those forged notes which had been printed

from the later plate. The distinctive mark was a small letter

at the corner of the design, which the Bank cashiers could have

read with an ordinary magnifying glass.

Both Mr. Justice Wright in the King's Bench, and the Court

of Appeal ruled that any of these distinguishable notes that

had been exchanged after the interval within which the necessary

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

394

THE ECONOMIC JOURNAL

[SEPT.

information as to the distinctive marks could have been obtained,

ought to be excluded from the claim for damages. There was

some difference of opinion as to the length of the interval, but that

is a matter of detail.

The House of Lords decided otherwise. They allowed the

cost of exchanging all the forged notes up to the 26th December,

1925, the interval prescribed by the Government for the process,

and ruled that the relatively negligible amount exchanged after

that date were honoured as an act of grace by the Bank. (As

they allowed a part of the assets recovered from the forgers to be

set against the notes exchanged after the 26th December, the

House of Lords in effect allowed even these to be included in the

claim.)

The ground for undertaking to exchange the forged notes

at all was the danger of discredit of the currency and consequent

panic. That was a matter of public interest on which it was for

the Government and not for the Bank of Portugal to take the

responsibility of deciding. Had the public interest not been in

question, the Bank might have invited holders to deposit their

500-escudo Vasco da Gama notes for a suitable period in order

that after scrutiny the genuine ones might be paid and the

forgeries rejected. There might perhaps have resulted a claim by

the Bank for damages in respect of its loss of credit and reputation,

but that is a hypothetical matter which it is not necessary to

pursue. The public interest required the complete relief of the

holders of the forged notes, the Government took the responsibility of authorising the Bank to exchange them, and the House

of Lords accepted the Bank's plea of the public interest. Since

the genuine 500-escudo Vasco da Gama notes constituted onesixth of the entire currency of the country, the consequences

of distrust (which would probably have spread to the rest of the

currency) would have been very serious indeed.

The Portuguese paper currency had been inconvertible into

gold ever since 1891. The escudo had fallen from its old parity

of 4s. 6d. to 2'd. Counsel for the defence argued, as Mr. Justice

Wright put it, that the Bank had euffered no loss because it had

simply exchanged pieces of paper which were not convertible

into gold for other pieces of paper which were also not convertible

into gold. This contention Mr. Justice Wright would not allow.

"In Portugal," he said, "the notes were the currency of the

country. They would purchase commodities, including gold.

They could buy foreign exchange, including sterling or dollars

or any currency which was convertible. They could do that

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1932]

TILE PORTUGUESE BANK NOTES CASE

395

because they had behind them the liability of the Bank of

Portugal."

In the higher Courts a minority of the judges took the contrary

view, and wanted to let off Waterlows with a liability for no

more than the cost of printing new notes to take the place of those

withdrawn (estimated at ?8,922).

On one point of principle Mr. Justice Wright was, I think,

in error, that is to say, in arguing that the notes " had behind

them the liability of the Bank of Portugal." An inconvertible

legal tender note is not a liability of the issuing bank at all, except

in the sense that for accounting purposes it must be entered

among the liabilities in the balance sheet. It cannot be " paid "

because it is itself the means of payment. The judges appear to

have taken for granted that a bank which issues legal tender notes

is obliged at any rate to go through the form of " paying " them

on demand- by handing out one note in exchange for another.

But I venture to doubt whether that is so, either in Portugal or

in England or anywhere else. If the bank of issue accepts one

of its notes from a holder, it simply becomes indebted to him for

the amount, and is thereupon able to discharge the debt with the

same note. Moreover, the bank of issue is under no general

legal obligation to receive its own notes at all except in

payment of debts due to it, though of course it may be obliged

by express statutory enactments to pay out new for soiled

notes, or small denominations for large, for the convenience of

the public.

In the case of the Bank of England, notes take the form of

promises to pay. But that makes no difference. The notes for

?1 and 10s. are legal tender in payments by the Bank, and the

words " I promise to pay " are merely ornamental so long as that

is so. They signify nothing more than the aspiration of the Bank

of England to return to the use of gold coin as hand-to-hand

currency at some time in the future. The notes of the Bank of

Portugal (like those of most Continental banks of issue) contain

no such formula. They do not even pretend to be debts, but are

simply money.

There is thus no liability incurred by a bank of issue when it

issues inconvertible notes. But that has no bearing on the

question of the loss incurred when it issues notes and does not

receive value for them. When that occurs, the bank is clearly

and inevitably so much the worse off.

If it issues notes to redeem forgeries, it can maintain the assets

received in exchange for its issues undiminished provided it can

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

396

THE ECONOMIC JOURNAL

[SEPT.

increase the total currency in circulation by the requisite amount.

That is an argument that deserves consideration. The effect of

the increased issue may be to depreciate the currency. But

Lord Warrington pointed out in the House of Lords that the

Bank of Portugal did not attempt to prove that they suffered

loss directly or indirectly by the increase in the currency and

the consequent depreciation of its purchasing power, or by

injury to their credit or interference in their relations with the

Government.

Their note issue was limited by law. In 1925 the note issue

included 1,640,000,000 against advances to the Government at a

nominal rate of interest, and a " commercial issue " which was

subject to a maximum limit of 195,630,000 escudos. At the time

the forgery was discovered the commercial issue amounted to

64,000,000. The forged notes had displaced a corresponding

amount of genuine notes and so encroached on the commercial

issue. The exchange of notes, which was contrary to law in

that the good notes were issued against no backing, made the

encroachment manifest.

The commercial issue was of course the profitable part of the

note issue, and had this encroachment upon it remained unrelieved,

the loss would have been obvious. But legislation soon followed

extending the Bank's power of issue. A decree of 19th July, 1926,

authorised an issue of 100,000,000 escudos to be repaid out of the

sums to be received from Waterlows, and a further addition

of 100,000,000 to the commercial issue. (A further sum of

125,000,000 to be used in colonial development does not seem to

have constituted an addition either to the advances to the Government or to the note issue.) Thus the Bank was empowered by

law to issue pieces of paper in exchange for pieces of paper.

Where then was its loss?

I do not think this line of argument can be sustained. The

note issue being limited by law, it cannot be assumed that in

extending the limit the legislative authority (in this case the

Government acting by decree) was guided by any other motive

than the public interest. If the public interest dictates the amount

of the currency, then the profits' of issue are correspondingly

limited. Any encroachment on the assets by which the issue is

backed and from which the profits are. derived is a dead loss to the

issuing authorities.

It may perhaps be objected that in the case of Portugal the

legislative authority avowedly did not determine the extension of

the note issue according to the public interest. Alongside the more

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1932]

THE PORTUGUESE BANK NOTES CASE

397

permanent increases was one of 100,000,000 which was expressly

redeemable out of the damages to be received from Waterlows.

It was a temporary extension. It was presumably in excess of

normal requirements, and its inflationary effect would be none the

less on account of its temporary character.

But it is in any case a mistake to suppose that a bank of issue

necessarily can recoup itself for its losses by increasing its issues.

Apart from any gold and foreign exchange that it may hold, its

assets are themselves expressed in the national currency unit

and are subject to the same depreciation as its note issue. Banks

of issue are not usually allowed to profit by an addition to the

currency value of their gold holdings through depreciation, and

it is unlikely that such other " real " values as the bank might

hold would be enough to safeguard its private capital against

depreciation.

A court of law may sometimes legitimately proceed on the

assumption that money remains invariable in value. But it

could hardly adhere to that assumption if it were at the same

time supposing that the issuing authority was free to increase

the supply of currency at its discretion.

It is not easy to formulate the monetary policy of Portugal

with precision. Up to 1924 the currency had been rapidly

depreciating and the escudo touched its minimum gold value of

2-8 cents (U.S.A.) in July 1924. By July 1925 it had recovered

to 5 1 cents, and at the time of the discovery of the forgeries in

December 1925 it had been pegged at that rate or about 96 to ?1

for five months. The pegging was effected by exchange control

rather than by convertibility. Nevertheless, the rate prevailing

in the illicit open market did not differ much from the official

rate. The official rate was modified to 99 to ?1 in 1927. In the

course of 1928 the open market rate, after fluctuating rather wildly

for a short time, was stabilised at about 108, the official rate

becoming merely the rate at which a certain portion of the foreign

exchange derived from the export trade was requisitioned by the

Government.

At last, in June 1931, the exchange was stabilised by law at

110 to ?1.

Whatever the precise significance of these measures may

have been, they at any rate imply a serious preoccupation with

the exchange value of the currency and a desire to guard against

a recrudescence of depreciation. And there is no evidence to

show that the extension of the issues in 1926 either was intended

to allow a further depreciation or actually had that effect. In

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

398

THE ECONOMIC JOURNAL

[SEPT.

1932

fact the note issue did not vary materially in the period 1925-7,

as the following figures show a

Note Issue.

Dec.

Dec.

Dec.

Dec.

Dec.

(Millions of escudos.)

1924

.

.

1925

1926

.

.

.

1927

.

.

.

.

.

1928

.

.

.

1763

1821

1854

1857

1976

It was only when a stable free open market rate was attained

in 1928 that the note issue increased to any material extent.

The Portuguese authorities were pursuing an eminently sane

and rational monetary policy. Their methods may not have been

above criticism, but any device for compensating the Bank of

Portugal for its losses by a bit of inflation would have been

flagrantly inconsistent with that policy. The " piece of paper"

argument was utterly out of place.

The upshot would. seem, therefore, to be that justice was

done. The House of Lords rejected all the fallacious arguments,

and arrived at the correct decision.

If the view of the dissentient judges makes some appeal

to common-sense, that is perhaps because it is hard on the manufacturer whose scale of financial operations is based on the mere

cost of production of the notes to be exposed by an accident

to a liability of an entirely different order of magnitude, arising

from the face value of the notes. A fraud of this kind is an

accident. There may be negligence. But even if Messrs.

Waterlow were negligent, that was not part of the case. It was

not material to their liability for breach of contract. Consequently, the fraud may be regarded as a mere accident, and

the question was, who was to bear the loss ? Was it to be those

who manufactured the notes or those who used them ? The

ground for placing it upon the manufacturers was that it was they

whose precautions (whether negligently taken or not) failed to

prevent the fraud. A manufacturer of explosives assumes a

certain liability for accidents, and he cannot pass it on to his

customers on the ground that they procured him to manufacture

the dangerous product. The apparatus for the manufacture of

bank notes has an explosive quality, and whoever undertakes

the business does so at his peril.

R. G. HAWTREY

This content downloaded from 14.139.214.181 on Sat, 6 Dec 2014 12:37:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

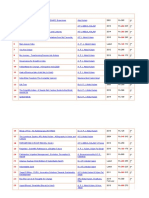

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Europe Landmarks Reading Comprehension Activity - Ver - 1Dokument12 SeitenEurope Landmarks Reading Comprehension Activity - Ver - 1Plamenna Pavlova100% (1)

- 360-Degree FeedbackDokument24 Seiten360-Degree Feedbackanhquanpc100% (1)

- SSRN Id2600379Dokument37 SeitenSSRN Id2600379Neeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lincoln LawyerDokument6 SeitenLincoln LawyerNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vision IAS Jan 2015Dokument77 SeitenVision IAS Jan 2015Harshal ErNoch keine Bewertungen

- VISION November 2015-1-15 November by Xaam - inDokument42 SeitenVISION November 2015-1-15 November by Xaam - inDrRaanu SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSRN Id2267002Dokument6 SeitenSSRN Id2267002Neeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rse 16092016 S 24392012Dokument94 SeitenRse 16092016 S 24392012Gaurav PathakNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSBDADokument3 SeitenBSBDANeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IdfDokument2 SeitenIdfNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compensation Through Writ Petitions An Analysis of Case LawDokument8 SeitenCompensation Through Writ Petitions An Analysis of Case LawNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Automated Data FlowDokument2 SeitenAutomated Data FlowNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSBDADokument3 SeitenBSBDANeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A-60-222 Question of Antarctica (Report of The Secretary-General)Dokument22 SeitenA-60-222 Question of Antarctica (Report of The Secretary-General)Neeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSRN Id2600379Dokument37 SeitenSSRN Id2600379Neeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asian Clearing UnionDokument2 SeitenAsian Clearing UnionNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Theory of The Firm and The Theory of The International EconomDokument87 SeitenThe Theory of The Firm and The Theory of The International EconomBejmanjinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annual Return FEMADokument6 SeitenAnnual Return FEMANeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic SavingDokument3 SeitenBasic SavingNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banking Sector in IndiaDokument9 SeitenBanking Sector in IndiaNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LLM Schedule 2015 16 2Dokument7 SeitenLLM Schedule 2015 16 2Neeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study Programmes English StudyinczDokument132 SeitenStudy Programmes English StudyinczNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Centre Alotment SSCW JAG 16nDokument17 SeitenCentre Alotment SSCW JAG 16nNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fema Act 1999Dokument22 SeitenFema Act 1999vishalllmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antarctic BioprospectingDokument36 SeitenAntarctic BioprospectingNeeraj Mandaiya100% (1)

- Cosi Cimet Curriculum1Dokument20 SeitenCosi Cimet Curriculum1Neeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPGG AnnouncementDokument4 SeitenPPGG AnnouncementsteelyheadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ch6 SurveyDokument11 SeitenCh6 SurveyNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book 8Dokument11 SeitenBook 8nadin_90Noch keine Bewertungen

- ATS and CanadaDokument2 SeitenATS and CanadaNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sanjay Chaturvedi SymposiumDokument1 SeiteSanjay Chaturvedi SymposiumNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 18 Joyner PoliticsDokument3 Seiten18 Joyner PoliticsNeeraj MandaiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applied Thermodynamics - DraughtDokument22 SeitenApplied Thermodynamics - Draughtpiyush palNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maule M7 ChecklistDokument2 SeitenMaule M7 ChecklistRameez33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Narcissist's False Self vs. True Self - Soul-Snatching - English (Auto-Generated)Dokument6 SeitenNarcissist's False Self vs. True Self - Soul-Snatching - English (Auto-Generated)Vanessa KanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samsung LE26A457Dokument64 SeitenSamsung LE26A457logik.huNoch keine Bewertungen

- KalamDokument8 SeitenKalamRohitKumarSahuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 Facilitator's Guide - Assessing Information NeedsDokument62 SeitenModule 1 Facilitator's Guide - Assessing Information NeedsadkittipongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kofax Cross Product Compatibility MatrixDokument93 SeitenKofax Cross Product Compatibility MatrixArsh RashaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnnulmentDokument9 SeitenAnnulmentHumility Mae FrioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sayyid DynastyDokument19 SeitenSayyid DynastyAdnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- TEsis Doctoral en SuecoDokument312 SeitenTEsis Doctoral en SuecoPruebaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employer'S Virtual Pag-Ibig Enrollment Form: Address and Contact DetailsDokument2 SeitenEmployer'S Virtual Pag-Ibig Enrollment Form: Address and Contact DetailstheffNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15.597 B CAT en AccessoriesDokument60 Seiten15.597 B CAT en AccessoriesMohamed Choukri Azzoula100% (1)

- Dummies Guide To Writing A SonnetDokument1 SeiteDummies Guide To Writing A Sonnetritafstone2387100% (2)

- Weill Cornell Medicine International Tax QuestionaireDokument2 SeitenWeill Cornell Medicine International Tax QuestionaireboxeritoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Port of Surigao Guide To EntryDokument1 SeitePort of Surigao Guide To EntryNole C. NusogNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLP No. 10 - Literary and Academic WritingDokument2 SeitenDLP No. 10 - Literary and Academic WritingPam Lordan83% (12)

- Psychology and Your Life With Power Learning 3Rd Edition Feldman Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDokument56 SeitenPsychology and Your Life With Power Learning 3Rd Edition Feldman Test Bank Full Chapter PDFdiemdac39kgkw100% (9)

- Hypnosis ScriptDokument3 SeitenHypnosis ScriptLuca BaroniNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is SCOPIC Clause - A Simple Overview - SailorinsightDokument8 SeitenWhat Is SCOPIC Clause - A Simple Overview - SailorinsightJivan Jyoti RoutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept of HalalDokument3 SeitenConcept of HalalakNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Parenting DnaDokument4 SeitenMy Parenting Dnaapi-468161460Noch keine Bewertungen

- CrisisDokument13 SeitenCrisisAngel Gaddi LarenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q3 Lesson 5 MolalityDokument16 SeitenQ3 Lesson 5 MolalityAly SaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science Project FOLIO About Density KSSM Form 1Dokument22 SeitenScience Project FOLIO About Density KSSM Form 1SarveesshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland)Dokument11 SeitenAlice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland)Oğuz KarayemişNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9francisco Gutierrez Et Al. v. Juan CarpioDokument4 Seiten9francisco Gutierrez Et Al. v. Juan Carpiosensya na pogi langNoch keine Bewertungen

- La Fonction Compositionnelle Des Modulateurs en Anneau Dans: MantraDokument6 SeitenLa Fonction Compositionnelle Des Modulateurs en Anneau Dans: MantracmescogenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer Pricing 8Dokument34 SeitenTransfer Pricing 8nigam_miniNoch keine Bewertungen