Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Heavy Metal

Hochgeladen von

Jose Carlos Azorín HernándezOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Heavy Metal

Hochgeladen von

Jose Carlos Azorín HernándezCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Metal, Rock, and Jazz: Perception and the Phenomenology of Musical Experience by Harris M.

Berger

Review by: Mikel J. Koven

The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 116, No. 459, Creolization (Winter, 2003), pp. 120-121

Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of American Folklore Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4137949 .

Accessed: 12/02/2015 04:02

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Illinois Press and American Folklore Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to The Journal of American Folklore.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 155.54.92.31 on Thu, 12 Feb 2015 04:02:17 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

120

JournalofAmericanFolklore116 (2003)

of many mythological animals (griffins, centaurs, giants, cyclopes, and so forth) was

influencedby the ancients'attemptsto explain

the large fossilized bones that littered their

landscape. Mayor argues, for example, that

griffins are derived from the bones of

Protoceratopsand Psittacosaurusin ancient

Scythia (chapter 1); that the monster on a

Corinthianvase (fig. 4.2) is an effectiverepresentation of a fossil skull weatheringout of a

cliff; and that the bones identified by the ancients as those of giants and mythical heroes

were in fact fossil bones (chapter 3). Mayor

writesentertainingly,and this book has almost

more of the tone of a voyageof discoverythan

a scholarlywork. In some places,this is rather

frustrating;in particular,I found referencesto

both ancient works and modern scholarship

sometimes lacking in the footnotes (e.g., who

is the "Romanpoet" on p. 141;and try matching the researchon pp. 165-66 with the sources

in n. 4. Surelymore than one endnote per page

is permissible!).Giventhe patchynatureof her

ancient sources,much of the book is necessarily speculative, perhaps rather more so than

Mayorindicatesin her text. But her researchis

intensive,her evidencestrong,and her conclusions (by and large) persuasive.

The book is significantlyflawed,I think, by

Mayor'sfailureto take into accountthe difference in date and genre between her texts.

Mayor'ssources range over a thousand years;

the evidence,which appearsstrongand obvious

when gatheredtogether,is in factdisparateand

scattered.Greeksand Romansbelongedto very

differentcultures,each one of which embraced

a number of shifting ideologies; the "ancient

Greco-Romans"(p. 224) are as much (and as

unlikely) a hybrid as many of the monsters

Mayordiscusses.The advancesin understanding madein the ancientworld (summarizedon

pp.226-27) did not occurto anyone individual

in the ancientworld,but werescatteredinsights.

Moreover,as she herself points out, ancient

scientific texts by and large tended to ignore

fossil finds, as they were far more concerned

with sortingand dealingwith whatthereis than

discussingwhat might have been. Most of her

sourcesareauthorswho dealtin the fabulousor

in travelers' tales, and who, in many cases,

should not be taken at face value, as Mayor

tends to do. They themselveswere often aware

that they wererecordingmarvels,not scientific

fact. Mayor'sparaphrasessometimes obscure

this distinction. For example, Phlegon's account of "the triple head of a human body

[which]had two sets of teeth"(BookofMarvels

11.1) becomes in Mayor's appendix "large

bones with threeskullsand two jawboneswith

teeth"(p. 271)-the human origin of the skulls

is lost, and they become "large"(Phlegon said

nothing about their size). Similarly,since photos are given of fossil bones, why not of the

Greek pots that she refersto, ratherthan her

own drawings?And in some placesshe is simply not criticalenough; for example, her suggestion that the bulls in BronzeAge bull-leaping frescoes represent the aurochs (p. 102)

assumes that the artists are depicting the animals in proportion and ignores the entire debateoverwhetherbull-leapingtook placeat all.

Despitethesecriticisms,thereis much in this

book that is valuableand interesting.In bringing togetherinto one placeall the sourcesdealing with the ancient understandingof fossils,

Mayorhas shed light on an almost unnoticed

sourceof ancientmythmaking.The finalchapter,on hoaxesor "palaeontologicalfictions,"as

Mayortermsthem, offerssome intriguingparallelsbetween the ancient and modern worlds

regardingthe interactionof imagination,myth,

and science. In spite of the reservationsabove,

I found her conclusions interesting and frequently persuasive.This is a stimulatingbook

and I hope thatit will provokethe interdisciplinary debatethat its author seeks.

Metal,Rock,and Jazz:Perceptionand the Phenomenology of MusicalExperience.ByHarris

M. Berger. (Hanover, N.H., and London:

WesleyanUniversityPress,1999.Pp.334, introduction, notes, glossary, index, 16 photographs.)

MIKEL J. KOVEN

Universityof Wales,Aberystwyth

HarrisBerger'sMetal,Rock,andJazzis a lengthy

and philosophicalaccount of how ethnomusicology can be informed by phenomenological

discourse.Throughhis fieldworkin the metal,

This content downloaded from 155.54.92.31 on Thu, 12 Feb 2015 04:02:17 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BookReviews

rock,andjazzscenesof ClevelandandAkron,

thesharedexBerger's

projectis to understand

periencesof the playersin musicalformation

withineachmusicaltraditionandwithintheir

respectivesocioeconomicand geographical

contexts.

Thebookbeginswithanethnographic

considerationof eachof thethree,mutuallyexclusive musicalcontexts-three separateclubs,

bands,andformsof popularmusic.Immediatelyone problemwith the projectemerges:

choiceof contrasts

andcomparisons

is

Berger's

neitherlinkednorreallyjustified.Clearlyhe is

mostinterested

in talkingaboutoneparticular

formof "heavymetal"rockmusic-so-called

deathmetal;in thesesectionsandchapters,

the

detail,and

paceof thewriting,theethnographic

the depthof interactionwithhis informants,

DannSaladin,allpickup.In conparticularly

trast,his otherdiscussionsof the Cleveland

"hardrock"scenewith the local band Max

Panicandhis comparisonof twojazzcontexts

elsewherein Ohio(onewhiteandoneAfrican

American

and

jazzensemble)arelesssuccessful

functionawkwardly.

In fact,onewonderswhy,

in thiseraof "publish

orperish,"

Bergerdidnot

breakthisworkdownintothreeseparate

books

thatcouldreference

eachother.

The sectionson death metal are strong

theirownvolume.Whatparenoughtowarrant

me in thesediscussions

was

ticularlyfascinated

informed

Berger's

ethnographically

exploration

of theconceptof "heaviness"

in music."Anyelementof the musicalsoundcanbe heavy,"he

states,"ifit evokespoweroranyof thegrimmer

emotions,andthehistoryof metaliscommonly

understood

asthepursuitof greater

andgreater

heaviness"

thelan(p.59).Thuscontextualizing

taxonoguageof rockfansthroughitsvernacular

mies,Bergergivesinsightintotheirworld.He

alsogivesperhaps

themostintelligent

of

analysis

I'veread(pp.72-73).

"moshing"

On the otherhand,Berger'sethnographic

descriptionsof the barswherehe observedthe

live musicalperformances

aremuchless successfulandarewrittenasif byrote.Hereis one

example:

Enteringthe mall'swide corridor,you see an

arrayof darkenedshopsand hearmusicfrom

speakersinset in the ceiling.Steppinginside

121

Rizzi's,youaregreetedby a hostesswearing

blackpants,a whiteshirtanda bowtie.On

mostnightsthewaitforatableisshort.Immespace

diatelybeforeyouis a largerectangular

dividedin half;tablesfortwoandfourfillthe

diningsection,anda lowwallandtwosmall

stepsupmarktheedgeof thelounge.(p.101)

Althoughthereis nothinginherentlywrong

to ethnography,

it is,to use

withthisapproach

inclua loadedphrase,boring.Theuninspired

sionof detailsliketheseis automaticandnever

queried.Andin thiscaseit shouldbe.

Muchof thebookis givenoverto defending

the author'sposition,of justifyinghis study,

andthesedimensionsinterrupttheworkunIt appearsthatBergeris tryingto

necessarily.

howis thisethnoghis

justify studyrepeatedly:

death

whenit is so obmetal,

raphy?

Whystudy

of popular

form

an

viously unimportant

fringe

music?Howis popularmusica worthy/legitiTheserepeated

matefocusfor our discipline?

attemptsto justifywhathe is doingbog the

readerdown.Bergerneedsto recognizethathe

to thechoir(whorecognize

is already

preaching

the legitimacyof the ethnographicstudyof

popularmusic,deathmetal,andtheexperience

andthathisarguments

of goingto nightclubs),

areunlikelyto makeanynewconvertsunless

theyarealreadyon theirown roadsto Damascus.

Berger'sreal contributionto ethnomusicologyin the bookis not the subjectstudied,

but his theoreticalorientationandmethodolhe doesnot

However,

ogy,hisphenomenology.

distinguishbetweenthe orthodoxphenomenologyof theearlytwentiethcentury(Bergson

and Husserl),and its development,problems,

overthepasthundred

changes,andreworkings

he

mention

the distinctions

Nor

does

years.

betweenorthodoxHusserlianphenomenology

and more recentdevelopmentssuch as Reader-

Theory.Finally,

TheoryorReception

Response

workis

so

although muchethnomusicological

artist-based,I hoped to see more consumer-

baseddiscoursein thisbook.Berger's

emphasis is so heavyon the positionof the culture

producerthat those readerswho do not make

music themselvesare often at a loss and probablymiss out on some importantphenomenological points for debate.

This content downloaded from 155.54.92.31 on Thu, 12 Feb 2015 04:02:17 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Dynamics of Bases F 00 BarkDokument476 SeitenDynamics of Bases F 00 BarkMoaz MoazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analyzing Evidence of College Readiness: A Tri-Level Empirical & Conceptual FrameworkDokument66 SeitenAnalyzing Evidence of College Readiness: A Tri-Level Empirical & Conceptual FrameworkJinky RegonayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The ADDIE Instructional Design ModelDokument2 SeitenThe ADDIE Instructional Design ModelChristopher Pappas100% (1)

- Week C - Fact Vs OpinionDokument7 SeitenWeek C - Fact Vs OpinionCharline A. Radislao100% (1)

- New Intelligent AVR Controller Based On Particle Swarm Optimization For Transient Stability EnhancementDokument6 SeitenNew Intelligent AVR Controller Based On Particle Swarm Optimization For Transient Stability EnhancementnaghamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leibniz Integral Rule - WikipediaDokument70 SeitenLeibniz Integral Rule - WikipediaMannu Bhattacharya100% (1)

- Unit Revision-Integrated Systems For Business EnterprisesDokument8 SeitenUnit Revision-Integrated Systems For Business EnterprisesAbby JiangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pengaruh Implementasi Sistem Irigasi Big Gun Sprinkler Dan Bahan Organik Terhadap Kelengasan Tanah Dan Produksi Jagung Di Lahan KeringDokument10 SeitenPengaruh Implementasi Sistem Irigasi Big Gun Sprinkler Dan Bahan Organik Terhadap Kelengasan Tanah Dan Produksi Jagung Di Lahan KeringDonny Nugroho KalbuadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Productivity in Indian Sugar IndustryDokument17 SeitenProductivity in Indian Sugar Industryshahil_4uNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Health Nursing Process Part 2Dokument23 SeitenFamily Health Nursing Process Part 2Fatima Ysabelle Marie RuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shortcut To Spanish Component #1 Cognates - How To Learn 1000s of Spanish Words InstantlyDokument2 SeitenShortcut To Spanish Component #1 Cognates - How To Learn 1000s of Spanish Words InstantlyCaptain AmericaNoch keine Bewertungen

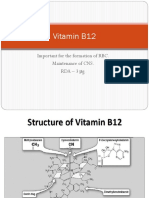

- Vitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceDokument19 SeitenVitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceHari PrasathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing The Marketing Mix: Notre Dame of Jaro IncDokument3 SeitenDeveloping The Marketing Mix: Notre Dame of Jaro IncVia Terrado CañedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portal ScienceDokument5 SeitenPortal ScienceiuhalsdjvauhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Identifying States of Matter LessonDokument2 SeitenIdentifying States of Matter LessonRaul OrcigaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grecian Urn PaperDokument2 SeitenGrecian Urn PaperrhesajanubasNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECON 121 Principles of MacroeconomicsDokument3 SeitenECON 121 Principles of MacroeconomicssaadianaveedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Determinants of Consumer BehaviourDokument16 SeitenDeterminants of Consumer BehaviouritistysondogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Score:: A. Double - Napped Circular ConeDokument3 SeitenScore:: A. Double - Napped Circular ConeCarmilleah FreyjahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper Is at DominosDokument6 SeitenResearch Paper Is at Dominosssharma83Noch keine Bewertungen

- ProbabilityDokument2 SeitenProbabilityMickey WongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Masala Kitchen Menus: Chowpatty ChatDokument6 SeitenMasala Kitchen Menus: Chowpatty ChatAlex ShparberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legend of GuavaDokument4 SeitenLegend of GuavaRoem LeymaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emotion and Decision Making: FurtherDokument28 SeitenEmotion and Decision Making: FurtherUMAMA UZAIR MIRZANoch keine Bewertungen

- Academic Transcript Of:: Issued To StudentDokument3 SeitenAcademic Transcript Of:: Issued To Studentjrex209Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yuri LotmanDokument3 SeitenYuri LotmanNHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grammar activities and exercisesDokument29 SeitenGrammar activities and exercisesElena NicolauNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2009 IBP ElectionsDokument77 Seiten2009 IBP ElectionsBaldovino VenturesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Awareness Training On Filipino Sign Language (FSL) PDFDokument3 SeitenAwareness Training On Filipino Sign Language (FSL) PDFEmerito PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- GUIA REPASO 8° BÁSICO INGLÉS (Unidades 1-2)Dokument4 SeitenGUIA REPASO 8° BÁSICO INGLÉS (Unidades 1-2)Anonymous lBA5lD100% (1)