Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Revisão de Livro - The End of Historicism

Hochgeladen von

Jarson Araújo0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

10 Ansichten2 SeitenRevisão do livro de Kai Arasola, The End of Historicism.

Originaltitel

Revisão de Livro - The end of historicism

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenRevisão do livro de Kai Arasola, The End of Historicism.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

10 Ansichten2 SeitenRevisão de Livro - The End of Historicism

Hochgeladen von

Jarson AraújoRevisão do livro de Kai Arasola, The End of Historicism.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 2

BOOK REVIEWS

Arasola, Kai J. The End of Historicism:Millerite Hermeneutic of Time Prophecies in

the Old Testament. [Uppsala]:Kai J. Arasola, 1990. 226 pp. $14.00.

The End of Historicism: Millerite Hermeneutic of Time Prophecies in the Old

Testament is a book with an intriguing title. The revised edition of an earlier

mimeographeddissertationsubmitted to the theological faculty of the University of Uppsala, it is a historicalcritical study of Millerism, and in particular

of William Miller and his evidences for the Second Advent in 1843.This book

is one of the latest in a series of similar studies by Millerite scholars such as

David T. Arthur (1970),Ingemar Linden (1971)' David L. Rowe (1974),Ronald

Numbers (1976), and Jonathan L. Butler (1987).

The book begins with a short historical background of Miller and his

movement. It is followed by a section on the context of historicism. The major

part of the book discusses the formation of Miller's views on prophecy,

hermeneutics, and exegesis, both chronological and nonchronological. It concludes with date-setting, topological interpretation, and the climax of the

revival.

Arasola views the Millerite movement as a turning point in the history

of prophetic exegesis. He sees it as a watershed in the history of millennialist

exegesis because it brought the end of historicism-the wellestablished historical method of prophetic exposition of time. It is from this perspective that

Arasola tries to discover Miller's exegesis, focusing especially on prophetic

chronologies related to 1843 and 1844.

On the roots of Miller's hermeneutic, Arasola departs from the majority

of Adventist scholars, who see it as being in harmony with the Reformation

hermeneutic. Arasola shows discontinuity between Reformation exegesis and

that of Miller. The context of Miller's view is historicism, which he identifies

as a by-product of Biblicism which replaced the Reformation hermeneutic of

Luther and Calvin during the post-Reformation era. Historicism is defined as

"the method of prophetic interpretation which dominated British and American exegesis from the late seventeenth century to the middle of the nineteenth

century" @. 28). Because some elements of this method go back to the Reformation and even to the early church, the author points out that historicism

must not be viewed as a new invention but as an integration of separate ideas

into a "coherent Biblist system" @. 29). Miller united all these elements into a

chronological prophetic system of interpretation.

Although much of the book's subject matter does not enlarge the horizons of those acquainted with the literature, Arasola makes a contribution

when he describes Miller's fifteen ways of calculating prophetic time. Whle

264

SEMINARYSTUDIES

many scholars have commented on various aspects of Miller's time prophecies

pertaining to 1843, they had no burden to go into all details of Miller's

expositions because these were not relevant to their research. Arasola's burden, however, is to look closely at every detail of the time prophecies, whether

or not they have any relevance for today.

The author states that he would not make an appraisal of Millerite

prophetic chronology by "today's exegetical criteria" because "one could

easily find reason to criticize his use of the Bible and his conclusions." No

attempt, therefore, would be made to evaluate Miller's conclusions as sound

or unsound but "simply to describe the evidence that the Millerites gave for

their prophetic time table." He stresses that any evaluation of Miller's exegesis

"must be done by the historicist criteria" (p. 86).

Subsequent discussion reveals that the author's methodological objectives are not realized. Time and time again he departs from his descriptive task

and reverts to an evaluation of Miller's exegesis from a historicalcritical

perspective.

With the disappointment in 1844, Arasola sees that Millerism and the

continuous historical interpretation of prophecy came to an end, being replaced by futurism and preterism. The remnantsof Miller's historicist approach,

Arasola notes, survive only among Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah's

witnesses.

This conclusion has not been supported by the facts. The author seems

totally unaware of Samuel Nufiez's doctoral research (The Vision of Daniel 8

[Andrews University Press, 19871). His findings on Daniel 8 clearly demonstrated that although from 1850 to 1900 the historicist school lost ground, the

majority of commentators continued to hold to the pre-1844 historicist view

of the little horn (Nuiiez, 392). This therefore invalidates Arasola's thesis on

the end of historicism.

Careful reading of the book reveals a number of inaccuracies that could

have been avoided.Among the most serious are the following: a) Both S. Snow

and G. Storrs are credited with advocating topological solutions to the time

calculations from February 1844 onward. There is evidence which shows that

Storrs did not come into the picture until the summer of 1844 with the

exposition of Matt. 25:l-10; b) I? G. Damsteegt is referred to as one who fails

to distinguish the Seventh-Month movement @. 16, n. 51), while in fact its

theological implications are discussed in more than 40 pages! (Foundations of

the Severlth-day Adventist Message and Mission [Eerdmans,19771, pp. 93-135);

c) Arasola favors the 1840 edition of Miller's rules over later edited versions.

Unfortunately, in the 1840 edition, rules IV, V, and XI1 are incorrectly copied.

One of them misses a whole sentence, together with all the textual evidence

@p.51-53).

One of the most useful aspects of the book are its extensive bibliography

and appendix. Unfortunately its lack of an index limits its practical usage.

Andrews University

I? GERARD

DAMSTEEGT

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Coming of The Comforter - L-1.E. Froom (1928)Dokument104 SeitenThe Coming of The Comforter - L-1.E. Froom (1928)Morgan Medlock60% (5)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Cultic Allusions in The Suffering Servant Poem DOUTORADODokument396 SeitenCultic Allusions in The Suffering Servant Poem DOUTORADOJarson Araújo100% (1)

- Christs Heavenly Sanctuary MinistryDokument6 SeitenChrists Heavenly Sanctuary MinistryJarson AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isaías 7.14 WegnerDokument18 SeitenIsaías 7.14 WegnerJarson AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poythress - Santos Altíssimo em Daniel 7 PDFDokument7 SeitenPoythress - Santos Altíssimo em Daniel 7 PDFJarson AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teste BaixadorDokument1 SeiteTeste BaixadorJarson AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

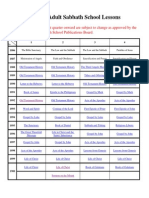

- Titles of Adult Sabbath School LessonsDokument8 SeitenTitles of Adult Sabbath School LessonsJarson AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- História e Escatologia em DanielDokument11 SeitenHistória e Escatologia em DanielJarson AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is God's Law Part of New CovenantDokument4 SeitenIs God's Law Part of New CovenantJarson AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre Advent JudgmentDokument4 SeitenPre Advent JudgmentJarson AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Era Da Igreja de LaodicéiaDokument2 SeitenA Era Da Igreja de LaodicéiaSandroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Catholic PrayersDokument2 SeitenBasic Catholic PrayersMarilyn AtienzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The River of Revival: ParallelDokument3 SeitenThe River of Revival: ParallelJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jansenism PresentationDokument7 SeitenJansenism Presentationapi-3053202120% (1)

- Notes On Personal PrayerDokument1 SeiteNotes On Personal Prayerapi-370553250% (2)

- Discipleship LessonsDokument11 SeitenDiscipleship LessonsJayco-Joni CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Will All Be Saved?Dokument8 SeitenWill All Be Saved?akimel100% (1)

- Bible Students Library (Russellites)Dokument116 SeitenBible Students Library (Russellites)Craig Martin100% (1)

- First Periodical Examination - CLE 8Dokument2 SeitenFirst Periodical Examination - CLE 8Luz Marie Corvera100% (1)

- SAMBUHAYDokument4 SeitenSAMBUHAYMab ShiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1970 Frankfurt DeclarationDokument5 Seiten1970 Frankfurt DeclarationFarman AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Easter StoryDokument7 SeitenThe Easter StoryAlbert HendraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The RosaryDokument9 SeitenThe RosaryAnne FrancesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Repentance PDFDokument5 Seiten5 Repentance PDFJuvyRupintaMalalisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Act of Consecration and Entrustment To Mary ImmaculateDokument2 SeitenAct of Consecration and Entrustment To Mary ImmaculateJERONIMO PAPANoch keine Bewertungen

- Are You Saved or NOTDokument14 SeitenAre You Saved or NOTRousseau Belmonte ApolonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 100 Truths About JesusDokument3 Seiten100 Truths About JesusA. HeraldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ordination Midterm Exam-ElderDokument7 SeitenOrdination Midterm Exam-Elderapi-280213838Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sermon Notes: What Is The Meaning of Being Born Again?Dokument2 SeitenSermon Notes: What Is The Meaning of Being Born Again?rubyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6.-Appreciating-the-Roots-of-the-Gospel-of-Jesus-intro-lecture 2Dokument12 Seiten6.-Appreciating-the-Roots-of-the-Gospel-of-Jesus-intro-lecture 2Ecal, Karyl Rose M.100% (1)

- Who Shall Separate UsDokument2 SeitenWho Shall Separate UsBernard LunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WEL - June 2012 English & TeluguDokument8 SeitenWEL - June 2012 English & Teluguraptureverysoon1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gospel From PatmosDokument12 SeitenGospel From PatmosTheoVarneyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behold The Condescension of God - Bruce R. McConkie ENDokument8 SeitenBehold The Condescension of God - Bruce R. McConkie ENjose vicencioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposed Covenant Hour of Prayers 5-9th of February 2024Dokument2 SeitenProposed Covenant Hour of Prayers 5-9th of February 2024agboitoprince3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Karai Kasang A MungdanDokument11 SeitenKarai Kasang A MungdanLahphai Awng LiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 24 Intro To SacramentsDokument5 SeitenChapter 24 Intro To SacramentsJoshuaAbadejosNoch keine Bewertungen

- HOPE676 Hope Sabbath School Outlines 2021 Q2 13Dokument1 SeiteHOPE676 Hope Sabbath School Outlines 2021 Q2 13AbelNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Epistle of St. Paul The Apostle To The LaodiceansDokument2 SeitenThe Epistle of St. Paul The Apostle To The LaodiceansHat RedNoch keine Bewertungen