Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Is Obesity A Risk Factor For Clostridium Difficile Infection?

Hochgeladen von

zernikevictoriaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Is Obesity A Risk Factor For Clostridium Difficile Infection?

Hochgeladen von

zernikevictoriaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Obesity Research & Clinical Practice (2015) 9, 5054

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Is obesity a risk factor for Clostridium

difcile infection?

Emma Punni a, Jaime L. Pula b, Fady Asslo c,

Walid Baddoura a,c, Vincent A. DeBari a,d,

a

Department of Medical Education, St. Josephs Regional Medical Center, Paterson,

NJ, USA

b Department of Pediatrics, St. Josephs Regional Medical Center, Paterson, NJ, USA

c Division of Gastroenterology, St. Josephs Regional Medical Center, Paterson, NJ,

USA

d Department of Internal Medicine, School of Health and Medical Sciences, Seton Hall

University, South Orange, NJ, USA

Received 29 October 2013 ; received in revised form 13 December 2013; accepted 13 December 2013

KEYWORDS

Clostridium difcile

infection;

Obesity;

Epidemiology;

Risk factors;

Body mass index

Summary

Background: The epidemiology of Clostridium difcile infection (CDI) has become

an important area of investigation, especially in light of the global increase in both

hospital-acquired (HA) and community-acquired (CA) CDI. Recently, obesity was

found to be associated with CDI and was suggested to represent an independent

risk factor for it.

Objective: We undertook a casecontrol study to examine obesity as an exposure

for both HA and CA cases in adults (age 18 years) admitted to a tertiary, universityafliated, acute care medical facility in the northeastern United States.

Methods: During the period January 2012July 2013, we examined cross-sectional

BMI data on 189 cases of CDI and 189 contemporaneous age and gender-matched

controls.

Results: We were unable to detect a statistically signicant difference between

the two groups; in fact, the BMI values for both groups were substantially equivalent (cases: median = 26.5 kg/m, IQR: 22.132.5; controls: median = 26.0, IQR:

22.731.0; p = 0.696). Odds ratios (and 95% condence intervals), evaluated at BMI

of 25, 30 and 35 kg/m2 , did not demonstrate statistical signicance.

Conclusion: These data suggest that obesity, as described by BMI, may not be a risk

factor for CDI in all populations.

2013 Asian Oceanian Association for the Study of Obesity. Published by Elsevier

Ltd. All rights reserved.

Corresponding author at: Department of Internal Medicine, School of Health and Medical Sciences, Seton Hall University, South

Orange, NJ, USA. Tel.: +1 908 309 3939.

E-mail address: Vincent.debari@shu.edu (V.A. DeBari).

1871-403X/$ see front matter 2013 Asian Oceanian Association for the Study of Obesity. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2013.12.007

Is obesity a risk factor for Clostridium difcile infection?

Introduction

Clostridium difcile infection (CDI) has become

an important nosocomial cause of morbidity and

mortality in the healthcare facility setting [1].

The result of CDI is diarrhoea, although the disease may progress to pseudomembranous colitis, a

severe inammation of the colon [2]. Because of

the scope and severity of CDI, its epidemiology and

potential therapeutic approaches to dealing with

it have achieved prominence over the past decade

[3,4].

Among the better known risk factors, antibiotic

use has come to be recognised as an exposure that

is independently associated with CDI. Studies have

also implicated the use of proton pump inhibitors

(PPI) [5,6], chronic renal failure [7], older age [8],

and chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression [9]

as risk factors. Hypoalbuminemia has also been

associated with CDI [10], and, along with diabetes mellitus, may be a risk factor for recurrence

[11].

A recent clinical investigation from Israel found

a strong association of obesity with CDI. In a

retrospective, casecontrol study, Bishara et al.

[12] found that the mean body mass index (BMI)

for a group of 146 cases of CDI (33.6 kg/m2 ,

SD: 4.3) was signicantly (p < 0.001) higher than

a matched control group (28.9 5.4 kg/m2 ). This

report has been the only such report to show

an association between obesity and CDI. We

sought to examine the possibility of obesity, as

evidenced by increased BMI, being an independent risk factor in our population of recent CDI

cases.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted at St. Josephs Regional

Medical Center, a 700 bed, university-afliated,

tertiary care, teaching hospital in the northeastern

United States. The protocol was submitted to the

Institutional Review Board and was granted exempt

status.

Subjects and protocol

Subjects were enrolled retrospectively during the

late summer of 2013 and included cases of CDI

observed during the period January 2012July

2013, inclusive. We included presumed cases of

CDI, based on clinical manifestation (diarrhoea)

51

and both the presence of C. difcile antigen

(glutamate dehydrogenase) and toxins A and B

as detected by the C.diff Quik Chek Complete

assay system (TechLab Inc., Blacksburg, VA, USA).

Patients with hepatic cirrhosis, HIV and those

being treated with chemotherapy for various malignancies were excluded. We also subdivided the

cases into those that were hospital acquired (HA)

and those that were community acquired (CA)

based on time from admission to time of presentation with CDI [13]. Cross-sectional data, on

admission, were obtained for BMI, and known risk

factors as well as demographics. Ultimately, 189

cases were enrolled. These cases were compared

with a group of 189 controls admitted during

the same period of time as the case cohort (1

January 201231 July 2013). The controls were

matched for age (3 years) and gender, and were

applied with the same exclusion criteria as the

cases (Hepatic cirrhosis, HIV positivity and those

being treated with chemotherapy for malignancies).

Statistical analysis

We powered the study to be able to detect a difference in BMI of 2 kg/m2 with a pooled SD of

5 kg/m2 and found that at a two-sided = 0.05,

we would achieve a power of >90% with case

and control groups of 189 subjects. Therefore, we

enrolled 189 adult (18 years) cases and the same

number of age (3 years) and gender-matched controls admitted during the period January 2012July

2013, inclusive. Univariate categorical associations

were analysed in contingency tables by Fishers

exact test for 2 2 tables and chi-square test for

2 n tables (race/ethnicity). Continuous data were

tested for normality by the DAgostino-Pearson

omnibus normality test. All were found to be

non-Gaussian and log transformations also did not

achieve distributions judged to be normal. Thus,

these data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) and two group-wise comparisons

were evaluated by a nonparametric statistical

method, the MannWhitney test. For baseline

characteristics to be considered as potential confounders, p-values 5 (p 0.25) were required.

Potential confounders that met this criterion were

to be included in a multivariable logistic regression

model only if the univariate analyses were statistically signicant, i.e., odds ratios (OR) not including

a value of 1.00 in the 95% condence interval (CI)

and p < 0.05 (two-sided). Data were analysed using

Prism software (GraphPad Corp., San Diego, CA,

USA) and SPSS v. 18 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

52

E. Punni et al.

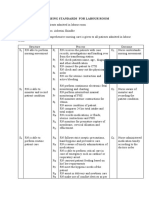

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the subjects. All continuous data are given as medians and interquartile range

(25th75th percentile); categorical data given as counts. Abbreviations: HA, hospital-acquired; CA, community

acquired; NA, not applicable; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; CHF, congestive heart failure; PPI, proton

pump inhibitors; H2RA, histamine type 2 receptor antagonists.

Parameter

Cases

Controls

p-Value

Age (years)

Gender (F/M)

Race/ethnicity

Black

Hispanic

White

Other

Albumin (g/dL)

HA/CA/indeterminate

DM

HTN

CHF

Fluoroquinolones

All antibiotics

PPI

H2RA

69 (5782)

103/86

70 (5681)

103/86

0.877

1.000

0.460

46

8

115

14

3.3 (2.83.8)

157/38/4

75/114

120/69

18/171

17/172

92/97

57/132

12/177

45

3

123

13

3.8 (3.34.2)

NA

61/128

115/74

16/173

13/176

58/131

34/155

6/183

Results

Baseline characteristics of the groups

Demographic characteristics (Table 1) reveal similarities in age, gender (patients were matched to

both these characteristics) and racial and ethnic

backgrounds. Hospital-acquired cases accounted

for 83% of all cases. Not unexpectedly, cases cohorts

were found to be hypoalbuminemic relative to controls and were found to be signicantly associated

with PPI (p = 0.008) and antibiotic usage (p = 0.001)

(excluding vancomycin and metronidazole, used to

treat CDI). Interestingly, our cases were not associated with uoroquinolone usage; however, this

study was not powered for that covariate and there

were relatively few patients in our groups (17 cases

and 13 controls who were treated with uoroquinolones).

Comparison of BMI in cases and controls

Of the cases, 36% were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2 ) and

of the controls 30% were found to be obese. There

was no signicant difference between cases and

controls in this regard (p = 0.258). We were unable

to detect a difference in the BMI of cases and controls (Fig. 1A). Median BMI for cases was 26.5 kg/m2

(IQR: 22.132.5); for controls the median was

26.0 kg/m2 (IQR: 22.731.0); p = 0.696. We, similarly, could not detect a statistically signicant

difference between HA (n = 146) and CA cases

(n = 39) (Fig. 2B), with medians and IQR for HA

<0.0001

NA

0.163

0.672

0.858

0.569

0.001

0.008

0.226

cases being 26.6 kg/m2 (21.632.3) and CA being

26.5 kg/m2 (22.233.0); p = 0.638 (Fig. 2B).

Effect size, as evaluated by OR and 95% CI

was evaluated at three levels of BMI: 25, 30 and

35 kg/m2 . These data are given in Fig. 2. At all BMI

levels evaluated, the lower 95% condence value

included unity, precluding any statistically signicant difference. Per protocol, these data were not

subjected to multivariable analysis in light of their

not suggesting a signicant association between BMI

and CDI.

Discussion

Given the rapid increase in the incidence of CDI

infection over the past decade, risk factor surveillance is clearly warranted. Patients, potentially

at risk for developing diarrhoea secondary to CDI,

when identied, could be monitored during their

hospital stay and subjected to therapeutic alterations which may decrease the likelihood of their

developing CDI. As an example, in the case of

stress ulcer prophylaxis, substituting type-2 histamine receptor antagonists for PPIs (the use of

which represents a well-established risk factor for

CDI) decreased the risk for developing CDI [5,6].

Several exposures that are associated with CDI,

namely hypoalbuminemia, advanced age and diabetes [11,1417] suggest that nutritional factors

may play a role in its development. Obesity is frequently a product of poor nutrition; in fact, it may

Is obesity a risk factor for Clostridium difcile infection?

Figure 1 BMI measurements for individuals enrolled in

the study. (A) Compares all cases with controls (n = 189

per group; p = 0.696). (B) Compares HA (n = 146) and

CA cases (n = 39) for which comparison the p-value was

0.638. Box and whisker plots show median (centre of the

box) and IQR (ends of box) with maximum and minimum

values at ends of error bars.

reect a state of malnutrition [18]. Thus, awareness of patients who are overweight or obese may

represent an approach to identifying subjects who

are potentially at risk for CDI.

In routine clinical practice, BMI is the most frequently used surrogate for body composition. It

has limitations based on its comparison to actual

Figure 2 OR for CDI at BMI of 25, 30 and 35 kg/m2 ; error

bars are 95% CI.

53

adiposity. In a recent study, Bishara et al. [12] evaluated BMI in 148 cases of CDI and 148 age and

gender-matched controls. They proposed that CDI

is associated with obesity, and this association was

based on the differences in BMI between these

groups.

In this study, we also examined the relationship

between BMI and CDI in a casecontrol model. Our

ndings do not conrm the purported association

between obesity and CDI. In fact, the subjects with

CDI had BMI values that were, at the median, barely

overweight and quite similar to the controls. The

reason for these discrepant results bears investigation. There is the possibility that the diets of

the populations represented by the sample cases

in the two studies are likely quite different. In

2012, Antunes et al. [19] provided new insights into

understanding the links between nutrient acquisition and virulence in C. difcile. One example is

the ability of C. difcile to use an extended range of

carbohydrates, which may be important during the

pathogenesis process (by means of promoting survival and growth in the intestine). Another example

is reected in the composition and development

of infant gut microbiota, namely C. difcile, as

inuenced by BMI, weight, and weight gain of mothers during pregnancy [20]. Hence, although it has

been reported that deviations in gut microbiota

composition may predispose towards obesity, and

specic groups of commensal gut bacteria may

harvest energy from food more efciently than

others obesity may not be an independent risk

factor for CDI. Physiologic factors related to the

degree of diversity in the case and control samples

may also be reective of the observed discrepancy.

As further conrmation of the role of diet in CDI,

while in Northeast-Brazil, Maciel et al. [21] investigated the effect of high doses of oral vitamin A and

suggested the role of retinol is also a protective

one with regards to early childhood diarrhoea associated with CDI. Furthermore, the effect of various

diets on C. difcile in mice has been established

[22] in addition to the negative role of an atherogenic diet fed to hamsters [23].

In our opinion, the characterisation of obesity

as a risk factor for CDI remains an open issue,

one perhaps best adjudicated from an investigational standpoint through the use of a better

surrogate of body composition such as the use of

body impedance analysis instrumentation [24] in a

prospective cohort of hospitalised patients. In lieu

of the results of such a study, currently planned

in our institution, we can only comment on our

present ndings that suggest that obesity may not

be a risk factor for CDI in all populations.

54

E. Punni et al.

Conict of interest statement

The authors have no conicts of interest, nancial

or otherwise, to disclose.

References

[1] Gould CV, McDonald LC. Bench-to-bedside review: Clostridium difcile colitis. Crit Care 2008;12:203.

[2] Freeman J, Bauer MP, Baines SD, Corver J, Fawley WN,

Goorhuis B, et al. The changing epidemiology of Clostridium difcile infections. Clin Microbiol 2010;23:529

49.

[3] Surawicz CM. Reining in recurrent Clostridium difcile infection whos at risk? Gastroenterology

2009;139:1524.

[4] Pacheco SM, Johnson S. Important clinical advances in the

understanding of Clostridium difcile infection. Curr Opin

Gastroenterol 2013;29:428.

[5] Jayatilaka S, Shakov R, Eddi R, Bakaj G, Baddoura WJ,

DeBari VA. Clostridium difcile infection in an urban medical center: ve-year analysis of infection with the use of

proton pump inhibiors. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2007;37:2417.

[6] Barletta JF, El-Ibiary SY, Davis LE, Nguyen B, Raney

CR. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk for hospitalacquired Clostridium difcile infection. Mayo Clin Proc

2013;88:108590.

[7] Eddi R, Malik MN, Shakov R, Baddoura WJ, Chandran C,

DeBari VA. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for

Clostridium difcile infection. Nephrology 2010;15:4715.

[8] Moshkowitz M, Ben-Baruch E, Kline Z, Shimoni Z, Niven M,

Konikoff F. Risk factors for severity and relapse of pseudomembranous colitis in an elderly population. Colorectal

Dis 2007;9:1737.

[9] Trudel JL. Clostridium difcile colitis. Clin Colon Rectal

Surg 2010;20:137.

[10] Dubberke ER, Reske KA, Yan Y, Olsen MA, McDonald LC,

Fraser VJ. Clostridium difcile-associated disease in a setting of endemicity: identication of novel risk factors. Clin

Infect Dis 2007;45:15439.

[11] Shakov R, Salazar RS, Kagunye SK, Baddoura WJ, DeBari VA.

Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for recurrence of Clostridium difcile infection in the acute care hospital setting. Am

J Infect Control 2011;39:1948.

[12] Bishara J, Farah R, Mograbi J, Khalaila W, Abu-Elheja O,

Mahamid M, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for Clostridium

difcile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:48993.

[13] Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson SL, Kammer P, Orenstein R,

Sauver JL, et al. The epidemiology of community-acquired

Clostridium difcile infection: a population-based study.

Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:8995.

[14] Salazar-Kagunye R, Shah A, Loshkajian G, Baddoura WJ,

DeBari VA. Association of decreased serum protein fractions with Clostridium difcile infection in the acute care

setting: a casecontrol study. Biomark Med 2012;6:6639.

[15] Cleary RK.Clostridium difcile-associated diarrhea and colitis: clinical manisfestations, diagnosis and treatment. Dis

Colon Rectum 1998;41:143549.

[16] Wang F, Ma X, Hao Y, Yang R, Ni J, Xiao Y, et al. Serum

glycated albumin is inversely inuenced by fat mass and

visceral adipose tissue in Chinese with normal glucose tolerance. PLoS ONE 2010;7:e51098.

[17] Henrich TJ, Krakower D, Bitton A, Yokoe DS. Clinical risk

factors for severe Clostridium difcile-associated disease.

Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:41522.

[18] Via M. The malnutrition of obesity: micronutrient deciencies that promote diabetes. ISRN Endocrinol 2012,

http://dx.doi.org/10.5402/2012/103472.

[19] Antunes A, Camiade E, Monot M, Courtois E, Barbut F, Sernova NV, et al. Global transcriptional control by glucose

and carbon regulator CcpA in Clostridium difcile. Nucleic

Acids Res 2012;40:1070118.

[20] Collado MC, Isolauri E, Laitinen K, Salminen S. Effect of

mothers weight on infants microbiota acquisition, composition, and activity during early infancy: a prospective

follow-up study initiated in early pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr

2010;92:102330.

[21] Maciel AA, Ori RB, Braga-Neto MB, Braga AB, Carvalho EB,

Lucena HB, et al. Role of retinol in protecting epithelial cell

damage induces by Clostridium difcile toxin A. Toxicon

2007;50:102740.

[22] Mahe S, Corthier G, Dubos F. Effect of various diets on toxin

production by two strains of Clostridium difcile in gnotobiotic mice. Infect Immun 1987;55:18015.

[23] Blankenship-Paris TL, Walton BJ, Hayes YO, Chang J.

Clostridium difcile infection in hamsters fed an atherogenic diet. Vet Pathol 1995;32:26973.

[24] Beeson WL, Batech M, Schultz E, Salto L, Firek A, DeLeon

M, et al. Comparison of body composition by bioelectrical

impedance analysis and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

in Hispanic diabetics. Int J Body Compos Res 2010;8:4550.

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Infusion Pumps, Large-Volume - 040719081048Dokument59 SeitenInfusion Pumps, Large-Volume - 040719081048Freddy Cruz BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hyperglycemia in Critically Ill Management (: From ICU To The Ward)Dokument20 SeitenHyperglycemia in Critically Ill Management (: From ICU To The Ward)destiana samputriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amanita PhalloidesDokument15 SeitenAmanita PhalloidesJair Carrillo100% (1)

- Skin Infection Lab ReportDokument6 SeitenSkin Infection Lab Reportthe someone100% (2)

- Jurnal Obesitas 2Dokument9 SeitenJurnal Obesitas 2zernikevictoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HBM Explains Health BehaviorDokument3 SeitenHBM Explains Health BehaviorAKbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMHS 15 Proceeding in Jakarta Indonesia Conference PDFDokument37 SeitenMMHS 15 Proceeding in Jakarta Indonesia Conference PDFzernikevictoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMHS 15 Proceeding in Jakarta Indonesia Conference PDFDokument37 SeitenMMHS 15 Proceeding in Jakarta Indonesia Conference PDFzernikevictoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug StudyDokument17 SeitenDrug StudyTherese ArellanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breast and Nipple Thrush - 280720Dokument6 SeitenBreast and Nipple Thrush - 280720Robbie WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of IV Meropenem in Current EraDokument38 SeitenRole of IV Meropenem in Current EraImtiyaz Alam SahilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hong Kong Dental Journal - Volume 2 - Number 2 - YuLeungDokument1 SeiteHong Kong Dental Journal - Volume 2 - Number 2 - YuLeungFebySiampaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drugs Induce Hematologic DisordersDokument3 SeitenDrugs Induce Hematologic DisorderspaymanmatinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Probiotics vs Prebiotics: Differences, Advantages, TrendsDokument5 SeitenProbiotics vs Prebiotics: Differences, Advantages, TrendsNaevisweloveuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 155 Anaesthesia For Transurethral Resection of The Prostate (TURP)Dokument8 Seiten155 Anaesthesia For Transurethral Resection of The Prostate (TURP)Verico PratamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emergency Contact ListDokument1 SeiteEmergency Contact ListthubanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis On HPV VaccineDokument8 SeitenThesis On HPV Vaccinegjftqhnp100% (2)

- Gender-Dysphoric-Incongruene Persons, Guidelines JCEM 2017Dokument35 SeitenGender-Dysphoric-Incongruene Persons, Guidelines JCEM 2017Manel EMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Standards for Labour RoomDokument3 SeitenNursing Standards for Labour RoomRenita ChrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ob Assessment FinalDokument10 SeitenOb Assessment Finalapi-204875536Noch keine Bewertungen

- CSL 6 - HT PE Groin LumpDokument5 SeitenCSL 6 - HT PE Groin LumpSalsabilla Ameranti PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complications After CXLDokument3 SeitenComplications After CXLDr. Jérôme C. VryghemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qip ProjectDokument13 SeitenQip Projectapi-534216481Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dental BS Delta 1500 PPO Benefit Summary 2018Dokument4 SeitenDental BS Delta 1500 PPO Benefit Summary 2018deepchaitanyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Pharmacy Management CH 3 Prescription and Prescription Handlind NotesDokument9 SeitenCommunity Pharmacy Management CH 3 Prescription and Prescription Handlind Notesi.bhoomi12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dr. Ayesha Latif's Guide to Airway ManagementDokument32 SeitenDr. Ayesha Latif's Guide to Airway ManagementAyesha LatifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Plasma Cell Dyscrasias: MGUS, Myeloma, Waldenstrom's and AmyloidosisDokument41 SeitenUnderstanding Plasma Cell Dyscrasias: MGUS, Myeloma, Waldenstrom's and AmyloidosisDr MonikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endocrine System: Capillary Glucose MonitoringDokument34 SeitenEndocrine System: Capillary Glucose Monitoringjoel david knda mj100% (1)

- AIDS (Powerpoint Summary)Dokument14 SeitenAIDS (Powerpoint Summary)iris203550% (2)

- Nursing Management of Nephrotic SyndromeDokument2 SeitenNursing Management of Nephrotic SyndromeMARYAM AL-KADHIMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cerebral Concussion - PresentationDokument19 SeitenCerebral Concussion - PresentationAira AlaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is ScabiesDokument7 SeitenWhat Is ScabiesKenNoch keine Bewertungen

- ImgDokument1 SeiteImgLIDIYA MOL P V100% (1)

- Kuisioner Nutrisi Mini Nutritional AssessmentDokument1 SeiteKuisioner Nutrisi Mini Nutritional AssessmentNaufal AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen