Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

On The Written Transmission of The Pātañjalayogaśāstra PHILIPP A. MAAS

Hochgeladen von

Matthew RemskiOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

On The Written Transmission of The Pātañjalayogaśāstra PHILIPP A. MAAS

Hochgeladen von

Matthew RemskiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

On the Written Transmission of the

Ptajalayogastra

PHILIPP A. MAAS

1 The Yogastra of Patajali with its oldest commentary, the socalled Yogabhya, is one of the most widely read or, at least, one

of the most often copied texts in the field of classical Indian Philosophy. I have been able to trace thirty-seven printed editions published from 1874 to 1992 and eighty-two MSS in public libraries in

India, Nepal, Pakistan, Europe and the USA.1

1.1 Not only do these high numbers indicate the popularity of

these texts for which, in accordance with the information provided by the colophons, I use the title Ptajalayogastra (PY)

whenever I refer to them collectively but also the fact that the

PY became the subject of at least three subcommentaries. The

most famous, without doubt, is the Yogastrabhyavykhy or

Tattvavairad (TV) of Vcaspatimira I, who must have lived at

some time between 890 and 984/985 AD (Srinivasan 1967: 63).

Although the exact dating of the PY is not conclusively determined, a considerable gap of time and substantial differences in

philosophical views clearly separates Vcaspati from the author(s)

I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Dr. Albrecht Wezler (University of Hamburg), to Dr. Harunaga Isaacson (University of Pennsylvania), and to

Prof. Dr. Claus Vogel (University of Bonn) for reading provisional versions of

this paper. Susanne Kammller, M.A. was kind enough to check my English.

1

I am currently preparing A Hand-list of Manuscripts and Printed Editions

of the Ptajalayogastra and the Commentaries thereon for publication.

88

PHILIPP A. MAAS

of the PY. This is even more true of Vijnabhikus Yogavrttika, which seems to have been composed in the latter half of

the 16th century.2

1.2 The third subcommentary is the Ptajalayogastravivaraa (YVi), which was edited on the basis of a single Malaylam MS and published under the title Pt[a]jala-YogastraBhya Vivaraam of akara-Bhagavatpda (Rama Sastri &

Krishnamurthi Sastri 1952). Whether or not the famous Advaitin

akara was the author of the YVi is, as far as I can see, not yet

decided, and I am not at all inclined to enter into that discussion

here. For my present purpose, it may be sufficient to emphasize

that the YVis importance for the history of Indian philosophy was

immediately realized by scholars in Europe, Japan and the USA.3

Even in India, in circles among modern Vedntins, the first complete edition of the YVi was echoed by a reconstruction of the first

chapter of PY as it was commented upon by the YVi-kra.4

1.2.1 To my knowledge, Wezler was the first to stress not only

the YVis philosophical importance but also its philological value.

Almost filled with enthusiasm, he sums up his Philological Observations (1983: 32):

... [T]o anyone experienced in dealing with problems of textual criticism it

becomes plain that the author of the Vivaraa knew or had before him a text

of the Y[ogastra]Bhya that is definitely older than that known to

Vcaspatimira and comes hence much closer to the original.

1.2.2 Wezler is perfectly right in claiming that the YVi-kra

based his commentary on a version of the PY that contained more

original readings than the printed editions nowadays available. The

2

For details see Larson & Bhattacharya 1987: 376.

See for example (in alphabetical order): Bronkhorst 1985, Hacker 196869,

Halbfass 1991, Mayeda 196869, Nakamura 198081, Oberhammer 1977,

Schmithausen 196869, Vetter 1979, Wezler 1983, Whaling 1977.

4

Vedavrata 1984. The edition adopts many more readings from the YVi than

the version of the PY printed together with the first complete edition of the

YVi. It lacks, however, a systematical approach.

3

On the Written Transmission of the Ptajalayogastra

89

relation of these versions to Vcaspatimiras TV is less clear. We

neither possess a critical edition of the TV nor a critical study of

the basic text commented upon. Therefore, Halbfass (1991: 223)

rightly demanded that:

[M]uch further study of the textual tradition or traditions ... is needed before

definite conclusions concerning the relative chronology of the Vivaraa and

the Vairad ... can be drawn.

1.3 Although we are still a long way from definite conclusions, our knowledge on the topic at hand has improved. Harimoto

has prepared a new critical edition of the first chapter of the YVi

considering more textual witnesses than were used for the first edition.5 In preparing a critical edition of the first chapter of the PY, I

not only utilized the new critical edition of the YVi for a reconstruction of its basic text, but also had the chance to personally discuss preliminary results with him.

In addition to this valuable textual witness, I could make use of

twenty-two printed editions and of twenty-five MSS in seven

scripts and from different regions of the Indian subcontinent. In the

first chapter the witnesses are at variance in nearly 2180 cases, of

which about 900 are substantial.

2 The variant readings do not allow us to reconstruct the history of

the PYs transmission in detail, because it is contaminated. While

preparing new copies, scribes often did not use a single exemplar

but compared several MSS. This process can be proved for a large

number of MSS containing so-called corrections in the margin of

the folio or elsewhere. There is no agreement with regard to the

question which of two or more possible readings is the original

one, and, in some cases, even corrections were corrected, pointing

to a double process of checking one MS against others.

Harimoto (1999: 314) uses five textual witnesses.

90

PHILIPP A. MAAS

Srinivasa Ayya Srinivasan has already assumed that contamination did not start in comparatively late times.6 This also holds

good for our text, as can be deduced from the fact that the textual

witnesses with the exception of some printed editions do not

form solid genetic groups,7 i.e., groups containing a high number

of common errors that most probably did not creep into the transmission independently. In other words, contamination shows itself

by the simple fact that no stemmatic hypothesis can satisfactorily

explain the relationships existing among all witnesses (West 1973:

36).

3 Although contamination has been a constant factor within the

transmission, its varying degrees have not altogether made stemmatical considerations impossible. There are several groups of witnesses discernible by the occurrence of errors shared by their members in a significant number but not in a regular pattern.

The two main groups are the Northern group and the Southern group. The first of these is represented by nearly all printed

editions and by all MSS from North and Middle India in Devangar, rad and Maithil script. The Southern group is represented by MSS in Telugu-Kannaa script, in Grantha and in

Malaylam script. The basic text of the YVi is also part of this

group. Both main groups contain regional subgroups, and some late

MSS from the South are difficult to sort into either of the two main

groups. This is most probably due to the contaminating influence of

the version transmitted by the Northern group which, in the course

of time, seems to have gained the status of a normative recension

and can, therefore, be designated as the Vulgate.

3.1 Within the Southern group the basic text of the YVi holds a

special position, as it does not show close affinities to any subgroup. Although, for example, it exclusively shares a number of

6

7

Srinivasan 1967, 1.1.11, p. 5.

Srinivasan 1967, 1.1.12, p. 6.

On the Written Transmission of the Ptajalayogastra

91

readings with a fairly old Malaylam MS, the total number of such

readings is far lower than one would expect from the fact that all

known MSS of the YVi are in Malaylam characters. If one takes

into consideration that the basic text of the YVi preserves primary

readings that are not shared by any other MS, its most likely position within the transmission is quite close to the common ancestor

of the Southern group.

On the other hand, the extraordinary testimonial value

(Wezler 1983: 32) of the YVi for a critical edition of the PY is

unfortunately limited by a number of factors. First of all, the YVi

has come down to us in quite a poor state of transmission. Even its

archetype (the common ancestor of all known MSS) contained a

considerable number of more or less obvious errors. Secondly, the

basic text of the YVi seems to have contained errors that are not

transmitted by any other witness. Moreover, while judging readings

from the YVi we have to keep in mind the possibility that

comparatively late versions of the PY have influenced its transmission, as scribes may have more or less consciously changed the

wording of the YVi according to their knowledge of the basic text.

Finally, the YVi-kra, as a creative writer, cannot be expected to

have slavishly stuck to his basic text. We always have to reckon

with the possibility that readings of the PY were ultimately invented by the YVi-kra himself, in order to adapt the meaning of

the basic text to his own philosophical views.8 Therefore, any reconstruction of the YVis basic text will always be fraught with a

substantial amount of uncertainty that can only be diminished by a

careful philological analysis of the YVi, on the one hand, and by

8

In dealing with the YVi we have to keep in mind Steinkellners remarks on

using commentaries as hermeneutical tools: On the one hand it is necessary to

use those explanations which prove to be useful for an understanding of the

basic text, and to distinguish these explanations according to their degree of

authority. And on the other hand the extensions and digressions are to be examined with regard to their testimony for a development of the doctrine. Finally, if

such development is to be met with, we have to pay attention to what extent this

development has influenced the plain explanatory parts of the comments, too.

(Steinkellner 1981: 283)

92

PHILIPP A. MAAS

comparing assumed readings with the rest of the transmission on

the other.

3.2 It is, of course, hazardous to propose any concrete dating

for the time when the transmission was divided into two groups,

but some general considerations may not be totally out of place. In

any case, we are looking for an early date, as MSS transmitting the

Vulgate are found in a vast geographical area comprising the whole

of the Indian subcontinent with the exception of the extreme south.

The period of time that has passed since this division must be long

enough for regional subgroups to have developed. If a critical study

of the TV should support Wezlers observations and demonstrate

that Vcaspati knew or had in hand a version containing typical

errors of the Vulgate, the latest possible dating would be towards

the end of the 9th century, although nothing prevents us from assuming a much earlier date.

4 Before discussing a number of variant readings capable of supporting the most basic assumptions of this general outline, it may

be useful to describe the principles of textual criticism applied for

the constitution of the text. A reading, in order to be adopted, has to

stand a triple test. It must fulfil each of the following criteria (West

1973: 48):

1.

2.

3.

[A reading] must correspond in sense to what the author intended to

say, so far as this can be determined from the context.

It must correspond in language, style, and any relevant technical points

... to the way the author might naturally have expressed the sense.

It must be fully compatible with the fact that the surviving sources give

what they do; in other words, it must be clear how the presumed original reading could have been corrupted into any different reading that is

transmitted.

These criteria have been developed in the field of Greek and

Latin classics, but to me they seem applicable in the field of Indian

philosophical texts as well, although we face some difficulties. We

usually neither know much about the author or the authors of a

On the Written Transmission of the Ptajalayogastra

93

given text, nor do we know much about the process of composing

philosophical texts. Nevertheless, judging variant readings must, of

course, involve considerations of language and style as well as of

the context in which they appear.

4.1 With these considerations in mind, we can take a look at

PY 1.45. The non-uniform transmission of this passage bears out

two stemmatic key facts:

1) The Vulgate is free from errors transmitted by the Southern

group.

2) The basic text of the YVi belongs to the Southern group.

Table 1

Southern Version of YBh 1.45

(simplified)

prthivasyor gandhamtrat1

skmo viaya;

gandhamtrasypi2

ligamtra, ligamtrasypy

aliga skmo viaya. na cligt

para skmam asti.

Vulgate of YBh 1.45

(simplified)

prthivasyor gandhatanmtra

skmo viaya;

pyasypi rasatanmtram, taijasasya

rpatanmtram, vyavyasya sparatanmtram, kasya abdatanmtram,

tem ahakra, asypi

ligamtram, ligamtrasypy

aliga skmo viaya. na cligt

para skmam asti.

1) Mag, Myt3, Tvy, Tjg; gandhamtrat{sva YVi}rpamtrateti EFg, YVi 337,2.

2) gandhatanmtrasypi Myt3, Tvt; **trasypi Tvy; gandham{tanm EFg}tra

{traligamtra<> EF}sva{om. EFg}rpamtrasypi EFg, YVi 337,3.

4.1.1 YS 1.4245 deals with a series of meditative states called

sampatti. This series consists of four sampattis which differ from

each other by the subtlety of their respective meditative object. YS

1.45 describes the utmost degree of subtlety: skmaviayatva

94

PHILIPP A. MAAS

cligaparyavasnam / Furthermore, having [even more] subtle

objects ends with [primordial matter, which is] free from any characteristic (aliga). The Bhya in its Vulgate version explains, in

the terms of skhya-metaphysics, why primordial matter is the

final depth layer of meditative objects:9

prthivasyor gandhatanmtra skmo viaya; pyasypi rasatanmtram, taijasasya rpatanmtram, vyavyasya sparatanmtram, kasya abdatanmtram, tem ahakra, asypi ligamtram, ligamtrasypy aliga skmo viaya. na cligt para skmam asti.

The subtle object[-level] of the earthen gross element is the subtle element

smell, and of the watery [gross element] it is the subtle element taste; of

the fiery it is the subtle element of form; of the windy it is the subtle element of touch; of the spacious [gross element] it is the subtle element of

sound; their [subtle object-level] is egoity, and the [subtle object-level] of

this is characteristic-only (ligamtra), and the subtle object[-level] of characteristic-only is [primordial matter, which is] free from any characteristic

(aliga). And there is nothing more subtle than [primordial matter, which is]

free from any characteristic.

Within the Southern group this passage is transmitted in two

versions. Three Grantha MSS read mtram instead of tanmtram

almost consistently, and, moreover, have nbhasasya instead of

kasya.10 More important is the common reading of some other

MSS belonging to the southern group including the basic text of

the YVi that read a shorter text:

prthivasyor gandhamtrat skmo viaya; gandhamtrasypi ligamtra, ligamtrasypy aliga skmo viaya. na cligt para

skmam asti.

The difference results from a loss of text in an early ancestor of

the Southern version. It can easily be explained by the double occurrence of asypi in two neighbouring lines of a common source.

Presumably, a scribe slipped from one line to the other and over9

For details see Oberhammer 1977: 198209.

These MSS are Mag, Tjg1 and Tjg2.

10

On the Written Transmission of the Ptajalayogastra

95

looked the intervening text. The surviving asypi would, in a second step, have been changed to gandhamtrasypi, in order to improve the intelligibility of the sentence. If these assumptions are

correct, the common source had around fourty akaras per line.

4.2 The non-uniform transmission of PY 1.29 bears out one

more stemmatic key fact:

3) The Southern group is free from errors transmitted by the

Vulgate.

Table 2

Southern Version of PY 1.29

(simplified)

Vulgate of PY 1.29

(simplified)

kicsya bhavati tata pratyakcetandhigamo ntarybhva ca

(YS 1.29). ye tvad antary vydhiprabhtayas, te tvad varapraidhnn

na bhavanti.

svapuruadaranam1 apy asya bhavati:

yathaivevara

uddha, prasanna, kevalo, nupasargas, tathyam api buddhe pratisaved

madya2 purua, ity

adhi{v.l.: va}gacchatti.

ki csya bhavati? tata pratyakcetandhigamo py antarybhva ca

(YS 1.29). ye tvad antary vydhiprabhtayas, te tvad varapraidhnn

na bhavanti.

svarpadaranam apy asya bhavati:

yathaivevara purua

uddha, prasanna, kevalo, nupasargas, tathyam api buddhe pratisaved

ya puruas, tam purua, ity evam

adhigacchati.

adhigacchati

1) EFg, Tvy.

2) EFg, Mag, Tvy, YVi 281,3.

[T]he [yogin], moreover, acquires, because of this [devotion to vara], the

realization of [his] inner consciousness (pratyakcetandhigama) and the nonexistence (or not coming into being) of hindrances (antarya) [on the yogic

path] (YS 1.29). Whatever hindrances there be, disease and so on, all these,

because of devotion to vara, do not come into being (or: do not exist). [T]he

[yogin] acquires even sight (or: knowledge) of his own Self (purua): As vara

is pure, clear, alone and free from trouble, so also is my Self here that experiences [its] buddhi. Thus [t]he [yogin] realizes.

96

PHILIPP A. MAAS

4.2.1 YS 1.29 deals with two benefits the yogin acquires by

devotion to vara (varapraidhna). It reads: tata pratyakcetandhigamo ntarybhva ca. Because of this [devotion to

vara, the yogin acquires] the realization of [his] inner consciousness (pratyakcetandhigama) and the non-existence (or not coming

into being) of hindrances (antarya) [on the yogic path].

The Vulgate-Bhya is of little help in determining the meaning

of pratyakcetandhigamo. It reads: svarpadaranam apy asya

bhavati / [T]he [yogin], moreover, gets sight (or: knowledge) [of

his (or: the)] own-form. This passage is difficult. On the one hand,

rpa form goes quite well with darana sight but the exact

meaning of svarpadaranam here and its relation to pratyakcetandhigamo from the stra is unclear. Should we assume that svarpadarana is not a gloss but rather states an additional result of

devotion to vara?

4.2.2 Both well-known commentators on the PY, Vcaspati

and Vijnabhiku, solve the problem in peculiar but ultimately unsatisfactory ways,11 and the YVi does not transmit the passage

under discussion.

11

Vcaspati comments: tata pratyakcetandhigamo py antarybhva ca

[YS 1.29] | pratpa vipartam acati vijntti pratyak sa csau cetana ceti

pratyakcetano vidyvn purua | tad anenevarc chvatikasattvotkarasapannd vidyvato nivartayati | pratca cetanasydhigamo jna svarpato

sya bhavat[i |] (TV 33,1921). From this [devotion to vara results the]

realization of a sentient being (cetana) that performs [mental acts] opposingly.

[To explain pratyak: it] performs [mental acts] (acati) opposingly (pratpa)

[means it] knows contrarily [to reality]. A sentient being (cetana) that performs [mental acts] opposingly [=] a person (purua) possessing ignorance.

With this [expression the author] differentiates [the ordinary person] from vara

who is endowed with the perfection of [perceiving his] eternal sattva [and therefore] possesses knowledge. As a sentient being (cetana) that performs [mental

acts] opposingly [t]he [yogin] acquires the realization [=] knowledge according to its own form.

This passage does not allow to reconstruct the TVs basic text in detail.

Vcaspatis interpretation of pratyakcetana may be caused by his difficulties in

interpreting svarpadarana from the basic text.

Vijnabhiku, on the other hand, comments (YV 89,12f.): svarpadaranam iti | asya pratco jvasya yat tttvikam rpa tasya sktkaro pi

bhavatty artha | Sight (or: knowledge) of [his] own form means he acquires

On the Written Transmission of the Ptajalayogastra

97

4.2.3 A quite simple solution is to accept a common reading of

two MSS, one in Grantha and the other in Malaylam characters,

that reads svapuruadaranam sight (or: knowledge) of the

[yogins] own Self (purua) instead of svarpadaranam. The

former reading, in my opinion, is a paraphrase of pratyakcetandhigamo realization of [his] inner consciousness from the

stra.

4.2.4 There may, however, remain some doubt about whether

svarpadarana is not, in fact, the more difficult reading, and

should, therefore, be regarded as primary. Although it cannot be

ruled out entirely that, in the course of transmission, svarpa was

deliberately changed to svapurua, it is much more likely that svarpa is simply the result of the loss of the akara pu. The remaining

svarua would then have been corrected to svarpa. This correction is quite obvious if one takes into consideration the similarity in

North Indian alphabets of ru and r on the one hand, and of a and

pa on the other.12

4.3 The following excerpt from the Bhya not only supports

svapurua as the original reading by supplying a suitable context,

but also contains a second error of the Vulgate.

4.3.1 yathaivevara uddha, prasanna, kevalo, nupasargas, tathyam api buddhe pratisaved madya purua, ity

adhigacchatti. Syntactically, this passage is in the form of a direct

construction with iti at the end. The main verb adhigacchati takes

up the stras adhigamo. The sentence before ity adhigacchati describes the content of the yogins spiritual realization. As vara is

pure, clear, alone and free from trouble, so also is my Self here that

experiences [its] buddhi. Thus [t]he [yogin] realizes.

4.3.2 A slip of a scribes eye got him to overlook the akaras

mad right behind pratisaved. As a result instead of pratisaved

madya only pratisaved ya survived. The second word can be

also the realization of the form which is the real (tttvika) [form] of the inner

individual soul (jva).

12

Bhler 1896: Tafel 4 and Tafel 4a.

98

PHILIPP A. MAAS

taken as a relative pronoun, although, of course, it does not fit syntactically.

In the course of transmission, two scribes, presumably, chose

different strategies to solve the syntactical problems caused by ya.

One scribe changed iti to tam, in order to construe an apodosis (ya

purua, tam adhigacchati), the other deleted ya.

4.3.3 As in the example discussed above, there is no absolute

certainty regarding the original reading. It is also possible, though

much less likely, that the original version neither contained the

possessive adjective madya nor the relative pronoun ya. I can

see no reason why madya should have been inserted here, and

its presumable loss is easy to explain. Moreover, there is a constant line of argumentation that leads from the Bhyas gloss of

pratyakcetandhigamo as svapuruadaranam to madya purua

ity adhigacchati.

5 The analysis of variant readings in PY 1.29 points to what, a

priori, could have been regarded as most likely. At first, to quote

Wezler once more (1983: 32), ...cases where what can be called

secondary transmission of a text turns out to be more valuable

than all extant MSS. taken together, are not rare in our discipline,

as are cases, I would like to add, where South Indian MSS are more

valuable than northern MSS, impressive examples being Raus observations on the transmission of Bhartharis Vkyapdya,13 as

well as the Jaiminyabrhmaa, a re-edition of which is currently

under preparation by Fujii and Ehlers (Ehlers 2000).

13

Rau 1977: 30; 1991: 4.

On the Written Transmission of the Ptajalayogastra

99

ABBREVIATIONS AND REFERENCES

(a) Texts

Ptajalayogastravivaraa. Pt[a]jala-Yogastra-Bhya-Vivaraa of akara-Bhagavatpda. Critically ed. with introduction by Polakam Sri

Rama Sastri and S. R. Krishnamurthi Sastri. (Madras Government Oriental Series, 94.) Madras 1952.

PY

Ptajalayogastra (YS along with YBh).

TV

Tattvavairad or Yogastrabhyavykhy by Vcaspatimira I.

Ptajalayogastri.

Vcaspatimiraviracitaksameta-r-Vysabhyasametni. ramasya paitai saodhitam. 4th edition. (1st

ed. 1904). (nandrama Sanskrit Series, 47.) Puyapattana [= Pune]

1978.

YBh

Yogastrabhya.

YS

Yogastra by Patajali.

YV

Yogavrttika by Vijnabhiku. Ptajalayogadaranam. Vcaspatimiraviracita-Tattvavairad-Vijnabhikukta-YogavrtikavibhitaVysa-bhyasametam. rNryaamirea ippapariidibhi saha

sampditam. Vras 1971.

YVi

Ptajalayogastravivaraa. In: Kengo Harimoto (ed.), A Critical Edition of the Ptajalayogastravivaraa. First Part. Samdhipda with

an introduction. A Dissertation in Asian and Middle Eastern Studies.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1999.

(b) Manuscripts and Catalogues

EFg

Mag

Myt3

Tjg1

Tjg2

Digital pictures of a palm leaf MS containing the PY in Grantha script

from the Library of the cole Franaise dExtrme-Orient, Centre de

Pondichry, Pondicherry. Shelf No. 287.

Digital pictures of a paper MS containing the PY in Grantha script

from the Adyar Library, Chennai. Running No. 24 (in Cat. Adyar).

Shelf No. PM 1420.

Digital pictures of a palm leaf MS containing the PY in Telugu script

from the library of the Oriental Research Institute, Mysore. Running

No. 35065 (in Cat. Mysore). Shelf No. P 1560/5.

Microfilm pictures of a palm leaf MS containing the PY in Grantha

script from the Tanjore Mahrja Serfojis Sarasvat Mahl Library,

Thanjavur. Running Nos. 9904 (in Burnell 1880) and 6703 (in Cat. Tanjore).

Microfilm pictures of a palm leaf MS containing the PY in Grantha

script from the Tanjore Mahrja Serfojis Sarasvat Mahl Library,

100

Tvt

Tvy

PHILIPP A. MAAS

Thanjavur. Running Nos. 9903 (in Burnell 1880) and 670 (in Cat. Tanjore).

Digital pictures of a palm leaf MS containing the PY in Telugu script

from the library of the Oriental Research Institute, Thiruvananthapuram. Running No. 13474 (in Cat. Trivandrum). Shelf No. 11837A.

Digital pictures of a palm leaf MS containing the PY in Malaylam

script from the library of the Oriental Research Institute, Thiruvananthapuram. Running No. 14371 (in Cat. Trivandrum). Shelf No.

622.

BURNELL, A[rthur] C[oke] 1880. A Classified Index to the Sanskrit Mss. in the

Palace of Tanjore. Prepared for the Madras Government. London.

Cat. Adyar = AITHAL, Parameswara 1972. Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit

MSS [in the Adyar Library], VIII: Skhya, Yoga, Vaieika and Nyya.

(The Adyar Library Series, 100.) Adyar, Madras.

Cat. Mysore = MARULASIDDAIAH, Gurusiddappa 1984. Descriptive Catalogue

of Sanskrit MSS [in the Oriental Research Institute, Mysore], IXV. Vol.

4B, 715 ed. by H. P. Malledevaru. Vol. 10: Vykaraa, ilpa, Ratnastra, Kmastra, Arthastra, Skhya, Yoga, Prvamms,

Nyya. (Oriental Research Institute Series, 144.) Mysore.

Cat. Tanjore = S[UBRAHMANYA] SASTRI, P[alamadai] P[ichumani] 1931. A

Descriptive Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Tanjore

Mahrja Serfojis Sarasvat Mahl Library, Tanjore, IXIX. Vol. 11:

Vaieika, Nyya, Skhya and Yoga. Srirangam.

Cat. Trivandrum = BHASKARAN, T. 1984. Alphabetical Index of Sanskrit

Manuscripts in the Oriental Research Institiute and Manuscript Library,

Trivandrum. Vol. 3: ya to a. (Trivandrum Sanskrit Series, 254.) Trivandrum.

(c) Secondary Sources

BRONKHORST, Johannes 1985. Patajali and the Yoga stras. Studien zur

Indologie und Iranistik 10: 191212.

BHLER, Georg 1896. Indische Palaeographie von circa 350 a. Chr. circa

1300 p. Chr. (Grundriss der Indo-Arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde, 1.11.) Strassburg.

EHLERS, Gerhard 2000. Auf dem Weg zu einer neuen Edition des JaiminyaBrhmaa. Berliner Indologische Studien 13/14: 128.

HACKER, Paul 196869. akara der Yogin und akara der Advaitin. Einige

Beobachtungen. In: G[erhard] Oberhammer (ed.), Beitrge zur Geistesgeschichte Indiens. Festschrift fr Erich Frauwallner aus Anlass seines

On the Written Transmission of the Ptajalayogastra

101

70. Geburtstages (= WZKSO 1213): 119148. Wien. (Reprint in Hacker

1978: 213242.)

1978. Kleine Schriften. Hrsg. von Lambert Schmithausen. (GlasenappStiftung, 15.) Wiesbaden.

HALBFASS, Wilhelm 1991. Tradition and Reflection. Explorations in Indian

Thought. New York.

LARSON, Gerald James & Ram Shankar BHATTACHARYA (eds.) 1987. Skhya. A Dualist Tradition in Indian Philosophy. (Encyclopedia of Indian

Philosophies, 4.) Delhi.

MAYEDA, Sengaku 196869. The Advaita theory of perception. In: G[erhard]

Oberhammer (ed.), Beitrge zur Geistesgeschichte Indiens. Festschrift

fr Erich Frauwallner aus Anlass seines 70. Geburtstages (= WZKSO

1213): 221239. Wien.

NAKAMURA, Hajime 198081. akaras Vivaraa on the Yogastra-Bhya.

The Adyar Library Bulletin 4445: 475485.

OBERHAMMER, Gerhard 1977. Strukturen yogischer Meditation. Untersuchungen zur Spiritualitt des Yoga. (sterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, philosophisch-historische Klasse, Sitzungsberichte, 322 = Verffentlichungen der Kommission fr Sprachen und Kulturen Sdasiens,

13.) Wien.

RAU, Wilhelm (ed.) 1977. Bhartharis Vkypadya [1]. Die Mlakriks nach

den Handschriften herausgegeben und mit einem Pda-Index versehen.

(Abhandlungen fr die Kunde des Morgenlandes, 42.4.) Wiesbaden.

(ed.) 1991. Bhartharis Vkypadya 2. Text der Palmblatthandschrift

Trivandrum S.N. 532 (= A). (Akademie der Wissenschaften und der

Literatur: Abhandlung der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse,

7.) Stuttgart.

SCHMITHAUSEN, Lambert 196869. Zur advaitischen Theorie der Objekterkenntnis. In: G[erhard] Oberhammer (ed.), Beitrge zur Geistesgeschichte Indiens. Festschrift fr Erich Frauwallner aus Anlass seines

70. Geburtstages (= WZKSO 1213): 329360. Wien.

SRI RAMA SASTRI, Polakam & S. R. KRISHNAMURTHI SASTRI (eds.) 1952.

Pt[a]jala-Yogastra-Bhya-Vivaraa of akara-Bhagavatpda.

Critically edited with introduction. (Madras Government Oriental Series, 94.) Madras.

SRINIVASAN, Srinivasa Ayya (ed.) 1967. Vcaspatimiras Tattvakaumud. Ein

Beitrag zur Textkritik bei kontaminierter berlieferung. (Alt- und NeuIndische Studien, 12.) Hamburg.

STEINKELLNER, Ernst 1981. Philological remarks on kyamatis Pramavrttikak. In: Klaus Bruhn & Albrecht Wezler (eds.), Studien zum

102

PHILIPP A. MAAS

Jainismus und Buddhismus. Gedenkschrift fr Ludwig Alsdorf (Alt- und

Neuindische Studien, 23): 283295. Wiesbaden.

VEDAVRATA (ed.) 1984. r-Ptajala-Yogastrabhyam. <rgovindabhagavatpjyapda-iya-paramahasa-parivrjakcarya-rakarabhagavat-kta-vivaranusri.> Hind-vivti-sahita. [Vol. 1: Samdhipda.] Vykhyt: Saccidnanda Yog Sarasvat.

VETTER, Tilmann 1979. Studien zur Lehre und Entwicklung akaras. (Publications of the De Nobili Research Library, 6.) Wien.

WEST, Martin L[itchfield] 1973. Textual Criticism and Editorial Technique

Applicable to Greek and Latin Texts. Stuttgart.

WEZLER, Albrecht 1983. Philological observations on the so-called Ptajalayogastrabhyavivaraa (Studies in the Ptajalayogastravivaraa I).

Indo-Iranian Journal 25: 1740.

WOODS, James Haughton (trans.) 1914. The Yoga-System of Patajali. Or the

Ancient Hindu Doctrine of Concentration of Mind, Embracing the

Mnemonic Rules, Called Yoga-Stras, of Patajali and the Comment,

Called Yoga-Bhshya, Attributed to Veda-Vysa, and the Explanation,

called Tattva-Vairad, of Vchaspati-Mira. (Harvard Oriental Series,

17.) Cambridge, Mass. (Reprint: Delhi 1992.)

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Tantric Argument-Transfiguration Philosophical Discourse Pratyabhijna-David LawrenceDokument26 SeitenTantric Argument-Transfiguration Philosophical Discourse Pratyabhijna-David Lawrenceitineo2012Noch keine Bewertungen

- Year 11 Physics HY 2011Dokument20 SeitenYear 11 Physics HY 2011Larry MaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Isvarapratyabhijnakarika of Utpaladeva With The Author'S VrttiDokument338 SeitenThe Isvarapratyabhijnakarika of Utpaladeva With The Author'S VrttiPeter69Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tomato & Tomato Products ManufacturingDokument49 SeitenTomato & Tomato Products ManufacturingAjjay Kumar Gupta100% (1)

- The Sutrapath of The Pashupata Sutras Peter BisschopDokument21 SeitenThe Sutrapath of The Pashupata Sutras Peter BisschopYusuf PremNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawerence On PratyabhijnaDokument41 SeitenLawerence On Pratyabhijnadsd8gNoch keine Bewertungen

- The ShramanaDokument18 SeitenThe ShramanaGirish Narayanan100% (2)

- Qalandar AmaliyatDokument2 SeitenQalandar AmaliyatMuhammad AslamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prakriti ChartDokument4 SeitenPrakriti ChartMatthew RemskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurgen Hanneder - Vedic and Tantric MantrasDokument21 SeitenJurgen Hanneder - Vedic and Tantric MantrasjesprileNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saiva Siddanta Thesis FinalDokument22 SeitenSaiva Siddanta Thesis FinalprakashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kiss of the Yogini: "Tantric Sex" in its South Asian ContextsVon EverandKiss of the Yogini: "Tantric Sex" in its South Asian ContextsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (4)

- Derrida PlatosPharmacyDokument57 SeitenDerrida PlatosPharmacyNicolaycineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses To Child Abuse, Transcript, Day 104Dokument125 SeitenRoyal Commission Into Institutional Responses To Child Abuse, Transcript, Day 104Matthew RemskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Felomino Urbano vs. IAC, G.R. No. 72964, January 7, 1988 ( (157 SCRA 7)Dokument1 SeiteFelomino Urbano vs. IAC, G.R. No. 72964, January 7, 1988 ( (157 SCRA 7)Dwight LoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meaning in Tantric Ritual-Alexis SandersonDokument81 SeitenMeaning in Tantric Ritual-Alexis Sandersonitineo2012Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hatley 2010 Tantric SaivismDokument14 SeitenHatley 2010 Tantric Saivismkamakarma100% (1)

- Kundalini by HatleyDokument11 SeitenKundalini by Hatleyhari haraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shiva: My Postmodern Ishta - The Relevance of Piety TodayVon EverandShiva: My Postmodern Ishta - The Relevance of Piety TodayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meaning of Ha Ha in Early Ha HayogaDokument28 SeitenMeaning of Ha Ha in Early Ha HayogaletusconnectNoch keine Bewertungen

- COMPARISION STUDY - Kashmir Shaivism and Vedanta AND Par AdvaitaDokument27 SeitenCOMPARISION STUDY - Kashmir Shaivism and Vedanta AND Par Advaitanmjoshi77859100% (3)

- B. Baumer - Deciphering Indian Arts KalamulasastraDokument9 SeitenB. Baumer - Deciphering Indian Arts KalamulasastraaedicofidiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saktismhathayoga LibreDokument33 SeitenSaktismhathayoga LibreGeorge PetreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hanneder ToEditDokument239 SeitenHanneder ToEditIsaac HoffmannNoch keine Bewertungen

- James Mallinson - Textual Materials For The Study of VajrolimudraDokument31 SeitenJames Mallinson - Textual Materials For The Study of Vajrolimudraxynog100% (1)

- Śaivism and The Tantric Traditions PDFDokument9 SeitenŚaivism and The Tantric Traditions PDFSeth PowellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hahayogas Early History From VajrayanaDokument21 SeitenHahayogas Early History From VajrayanaNicolas ChabolleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sanderson 2007 - Śaiva Exegesis of KashmirDokument248 SeitenSanderson 2007 - Śaiva Exegesis of KashmirSofiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ontological Hierarchy in The Tantrāloka of Abhinavagupta-Mrinal KaulDokument21 SeitenOntological Hierarchy in The Tantrāloka of Abhinavagupta-Mrinal Kaulitineo2012Noch keine Bewertungen

- Application Performance Management Advanced For Saas Flyer PDFDokument7 SeitenApplication Performance Management Advanced For Saas Flyer PDFIrshad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sanderson's EPHE Lectures On Tantric Shaivism: Long SummaryDokument8 SeitenSanderson's EPHE Lectures On Tantric Shaivism: Long SummaryChristopher Wallis100% (1)

- Haṭha Yoga - Entry in Vol. 3 of The Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism - James Mallinson - Academia - EduDokument11 SeitenHaṭha Yoga - Entry in Vol. 3 of The Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism - James Mallinson - Academia - Edushankatan100% (1)

- Yoga and Freedom - A Reconsideration of Patanjali's Classical YogaDokument52 SeitenYoga and Freedom - A Reconsideration of Patanjali's Classical YogaDanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nama Rupa Yoga YogisDokument26 SeitenNama Rupa Yoga YogisAna Funes100% (1)

- AS1 - Karen O'Brien-Kop PDFDokument11 SeitenAS1 - Karen O'Brien-Kop PDFMaria Iontseva50% (2)

- Dyczkowski, Mark S. G. - Kubjika The Erotic Goddess PDFDokument18 SeitenDyczkowski, Mark S. G. - Kubjika The Erotic Goddess PDFPerched AboveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whicher - Nirodha Yoga Praxis MindDokument67 SeitenWhicher - Nirodha Yoga Praxis MindCharlie HigginsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Amtasiddhi Hahayogas Tantric Buddh PDFDokument14 SeitenThe Amtasiddhi Hahayogas Tantric Buddh PDFalmadebuenosaires100% (1)

- James Mallinson - On Modern Yoga's Sūryanamaskāra and VinyāsaDokument3 SeitenJames Mallinson - On Modern Yoga's Sūryanamaskāra and VinyāsaHenningNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shiva Drishti and Other 9 Manuscripts - Sharada - Alm 28 - Shelf 9 - Birch Bark - Part1Dokument149 SeitenShiva Drishti and Other 9 Manuscripts - Sharada - Alm 28 - Shelf 9 - Birch Bark - Part1Dharmartha Trust Temple Library, Jammu100% (3)

- Malinivijayottara TantraDokument13 SeitenMalinivijayottara TantrahihaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jason Birch Namarupa Spring Issue 2015 Yogataravali PDFDokument7 SeitenJason Birch Namarupa Spring Issue 2015 Yogataravali PDFletusconnect100% (1)

- Tantra Loka - Overview by MARK DYCZKOWSKIDokument5 SeitenTantra Loka - Overview by MARK DYCZKOWSKIpranaji88% (8)

- Haṭhayoga’s Fortuitous Union of PhilosophiesDokument18 SeitenHaṭhayoga’s Fortuitous Union of PhilosophiesJayendra Lakhmapurkar100% (1)

- Amritasiddhi PDFDokument19 SeitenAmritasiddhi PDFAbhishekChatterjeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- वव कम तर ण ड Vivekamārtaṇḍa the Sun of DiscriminationDokument70 Seitenवव कम तर ण ड Vivekamārtaṇḍa the Sun of DiscriminationAkhil SaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advice On Asana in The Sivayogapradipika PDFDokument8 SeitenAdvice On Asana in The Sivayogapradipika PDFWituś Milanowski McLoughlinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Damage Book on Shabara Bhashya Volume 1Dokument752 SeitenDamage Book on Shabara Bhashya Volume 1ahnes11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 12 Elements of A Concept PaperDokument4 SeitenLesson 12 Elements of A Concept PaperTrending Now100% (2)

- Light on Tantra in Kashmir Shaivism - Volume 3Von EverandLight on Tantra in Kashmir Shaivism - Volume 3Viresh HughesNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Lamp On Sivas Yoga The Unification of PDFDokument37 SeitenA Lamp On Sivas Yoga The Unification of PDFMehwish FayazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bhartṛhari's influential works on language and poetryDokument11 SeitenBhartṛhari's influential works on language and poetryvivekishuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advaya Taraka Upanishad - EngDokument2 SeitenAdvaya Taraka Upanishad - EngrookeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Olivelle - Life of The Buddha - IntroductionDokument23 SeitenOlivelle - Life of The Buddha - Introductiondanrva0% (1)

- Goodding 2011 Historical Context of JīvanmuktivivekaDokument18 SeitenGoodding 2011 Historical Context of JīvanmuktivivekaflyingfakirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Change and Continuity in Indian Religion - Jan GondaDokument76 SeitenChange and Continuity in Indian Religion - Jan Gondaindology2100% (1)

- Workshop ModelDokument1 SeiteWorkshop ModelZack AzzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Recognition of Śiva Even in Conceptual CognitionDokument3 SeitenThe Recognition of Śiva Even in Conceptual CognitionChip WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Franco Around AbhinavaguptaDokument25 SeitenFranco Around AbhinavaguptaTyler Graham Neill100% (1)

- Roots of Yoga Sutra PDFDokument3 SeitenRoots of Yoga Sutra PDFjeenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torzsok - Search Meaning Tantric Ritual Saiva ScripturesDokument31 SeitenTorzsok - Search Meaning Tantric Ritual Saiva ScripturesCharlie Higgins100% (2)

- LakulasDokument77 SeitenLakulasGennaro MassaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hindu Manuscript 2Dokument273 SeitenHindu Manuscript 2BalingkangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gorakh Natha Sampradaya: PiligrimageDokument17 SeitenGorakh Natha Sampradaya: Piligrimageashish984100% (1)

- Embodiment and Self-Realisation: The Interface Between S An Kara's Transcendentalism and Shamanic and Tantric ExperiencesDokument15 SeitenEmbodiment and Self-Realisation: The Interface Between S An Kara's Transcendentalism and Shamanic and Tantric ExperiencesNițceValiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Foundation For Yoga Practitioners TOCDokument7 SeitenThe Foundation For Yoga Practitioners TOCpunk98100% (2)

- Transcript (Day 110) Royal Commission On Institutional Responses To Child Abuse (Mangrove Mountain)Dokument121 SeitenTranscript (Day 110) Royal Commission On Institutional Responses To Child Abuse (Mangrove Mountain)Matthew RemskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mindfulness For Fathers Giving Your Child Secret SpaceDokument4 SeitenMindfulness For Fathers Giving Your Child Secret SpaceMatthew RemskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The Practice of Buddhist Meditation According To The Pali Nikayas and Exegetical SourcesDokument22 SeitenOn The Practice of Buddhist Meditation According To The Pali Nikayas and Exegetical SourcesjamesilluminareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Studios and Soup KitchensDokument25 SeitenStudios and Soup KitchensMatthew RemskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Responsibility and Ethics in Marketing: Anupreet Kaur MokhaDokument7 SeitenSocial Responsibility and Ethics in Marketing: Anupreet Kaur MokhaVlog With BongNoch keine Bewertungen

- AReviewof Environmental Impactof Azo Dyes International PublicationDokument18 SeitenAReviewof Environmental Impactof Azo Dyes International PublicationPvd CoatingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lifting Plan FormatDokument2 SeitenLifting Plan FormatmdmuzafferazamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iso 30302 2022Dokument13 SeitenIso 30302 2022Amr Mohamed ElbhrawyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verbos Regulares e IrregularesDokument8 SeitenVerbos Regulares e IrregularesJerson DiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- UAE Cooling Tower Blow DownDokument3 SeitenUAE Cooling Tower Blow DownRamkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iron FoundationsDokument70 SeitenIron FoundationsSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opportunity Seeking, Screening, and SeizingDokument24 SeitenOpportunity Seeking, Screening, and SeizingHLeigh Nietes-GabutanNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Innovation and Its Characteristics of InnovationDokument4 SeitenWhat Is Innovation and Its Characteristics of InnovationMohd TauqeerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reduce Home Energy Use and Recycling TipsDokument4 SeitenReduce Home Energy Use and Recycling Tipsmin95Noch keine Bewertungen

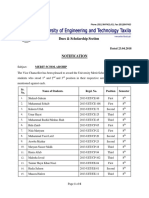

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDokument6 SeitenDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDNoch keine Bewertungen

- IC 4060 Design NoteDokument2 SeitenIC 4060 Design Notemano012Noch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of LeadershipDokument24 SeitenTheories of Leadershipsija-ekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetic Foot InfectionDokument26 SeitenDiabetic Foot InfectionAmanda Abdat100% (1)

- Sadhu or ShaitaanDokument3 SeitenSadhu or ShaitaanVipul RathodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transportation ProblemDokument12 SeitenTransportation ProblemSourav SahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alphabet Bean BagsDokument3 SeitenAlphabet Bean Bagsapi-347621730Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Secret Path Lesson 2Dokument22 SeitenThe Secret Path Lesson 2Jacky SoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portfolio ValuationDokument1 SeitePortfolio ValuationAnkit ThakreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Napolcom. ApplicationDokument1 SeiteNapolcom. ApplicationCecilio Ace Adonis C.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lcolegario Chapter 5Dokument15 SeitenLcolegario Chapter 5Leezl Campoamor OlegarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseDokument29 SeitenInflammatory Bowel Diseasepriya madhooliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ivan PavlovDokument55 SeitenIvan PavlovMuhamad Faiz NorasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Time Login Guidelines in CRMDokument23 SeitenFirst Time Login Guidelines in CRMSumeet KotakNoch keine Bewertungen