Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1

Hochgeladen von

Jobaiyer AlamCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1

Hochgeladen von

Jobaiyer AlamCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Asian Affairs, Vol. 30, No.

4 : 5-17, October-December, 2008

CDRB

publication

MUKTI BAHINI AND THE LIBERATION

WAR OF BANGLADESH : A REVIEW OF

CONFLICTING VIEWS

AHMED ABDULLAH JAMAL

Introduction

The liberation of Bangladesh was achieved through a nine-month long

war, in which all patriotic people of the country contributed from their

respective positions. The war started as a spontaneous resistance against

genocide by the Pakistan army, but soon assumed the character of an

organised war of attrition for the liberation of Bangladesh. It was essentially

a peoples war, which was epitomised by the army of freedom fighters known

as Mukti Bahini (MB) in Bangladesh. The war finally ended with the defeat

of the Pakistanis by the joint forces of MB and the Indian Army, which got

involved in the war at the last moment. The involvement of Indian forces

in liberating Bangladesh and the crucial role that it played in forcing the

Pakistanis to surrender, provides the ground for interpreting the role of

MB from different perspectives. In Bangladesh, freedom fighters are lauded

for being instrumental in liberating the country, although they are

assessed differently by other concerned parties % Pakistanis and Indians.

As a result, there exist at least three distinct views regarding the role of

Mukti Bahini in the liberation war: the Pakistani and the Indian views

as well as the self-assessment of the freedom fighters themselves.

This paper tries to introduce these conflicting views and revisit the

actual role played by the freedom fighters of Bangladesh in liberating their

country. The article has been written on the basis of analysis and

assessments made mostly by people who were involved in the war, either

in the battlefields or as researcher, or both. Pakistani and Indian views

have been taken from the writings of their respective military

commanders, while those views have been substantiated or negated by

quoting Mukti Bahini sources. Though all the views quoted in the article

have arguably been influenced by the personal as well as collective

interests of the concerned authors, one can identify such limitations and

see the true state of affairs through a variety of different interpretations

and assumptions.

CopyrightCDRB, ISSN 0254-4199

ASIAN AFFAIRS

Background of the War

The liberation war of Bangladesh in 1971 was a logical conclusion of

the Bengali nationalist movement that started soon after the formation of

Pakistan in 1947. The movement, based on the nationalistic aspirations

of the Bengalis living in erstwhile East Pakistan, was fuelled by the

continuous neglect of Bengalis and their interests by the Pakistani rulers.

The nationalist movement reached its high point when Yahya Khan, the

then President of Pakistan, refused to hand over power to Awami League,

the party which received absolute majority in East Pakistan in the national

elections of 1970. In protest, a non-cooperation movement was launched

by Awami League. Addressing a mammoth rally in Dhaka on March 7,

1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the absolute leader of East Pakistan at

the time, declared: This struggle is the struggle for freedom, this struggle

is the struggle for independence.1 In the same speech, Mujib also asked

the people to continue the struggle even if he could not give any more

orders.2 However, instead of accommodating the majority party, military

rulers of Pakistan chose the path of confrontation. The volatile situation

exploded when the Pakistani rulers resorted to brute force and genocide

to suppress the struggle of the Bengalis to achieve self-rule. In this sense,

the indiscriminate use of military force by the Pakistan Army, which was

initiated on the March 25, 1971 served as the immediate cause of the

Bangladesh war of liberation.

Genesis of Mukti Bahini

All freedom fighters were generally known as Mukti Bahini (MB). There

were two broader sections among them: those who came from military,

paramilitary and police forces were called Niyomito Bahini (regular forces),

while the freedom fighters from a non-military background were referred

to as Gonobahini (peoples forces). The names were given by the government

of Bangladesh. To the Indians, however, the Niomito Bahini was known as

Mukti Fouj (MF), and the Gonobahini as Freedom Fighters (FF).3

The regular forces of MB were created from among those Bengali troops

in Pakistan who revolted and joined the Liberation War. According to

Pakistan army sources, there were about 5,000 regular soldiers from six

battalions of East Bengal Regiment (EBR), 16,000 troops from East Pakistan

Rifles (EPR) and 45,000 Police posted in the then East Pakistan4. Most of

these Bengali troops, particularly soldiers, NCOs and junior officers were

strongly influenced by the ongoing nationalist movement, and were

psychologically prepared to play their role in liberating Bangladesh.

However, they had taken an oath of loyalty to preserve the integrity of

Pakistan, and could violate that only when they were asked by a superior

6

MUKTI BAHINI AND THE LIBERATION WAR OF BANGLADESH

authority, i.e., the Bengali political leadership, which was the only

recognized authority in East Pakistan at the time. Besides, they were

scattered, without any unified Bengali command. Some of the officers

sought instructions from the political leadership through friends/relatives,

but no concrete guidelines came.5 The general expectation was that a

last moment political solution would be reached. As a result, most of the

Bengali troops revolted at the eleventh hour, in many cases only after

they were attacked or about to be disarmed by Pakistani troops. This often

resulted in unplanned confrontations and casualties on the part of Bengali

troops.

It should be mentioned, however, that some courageous officers took

the grave risk of revolting without any specific directives from the political

leadership. Among them were Major (Retd.) Rafiqul Islam,6 Major Gen

(Retd.) Shafiullah,7 Major General (later President of Bangladesh) Ziaur

Rahman, Major general (later killed in a military coup) Khaled Mosharraf

and a few others. But there were instances where most of the Bengali

troops were wiped out by the Pakistanis due to lack of timely initiative on

the part of the officers.8

Although the war of resistance by Bengali troops and civilians started

spontaneously after the Pakistan army crackdown on March 25, 1971, the

war was fought by separate units and groups without any central

coordination. The first attempt to coordinate war efforts was made on April

4, 1971 in Teliapara (Sylhet), where a number of senior Bengali military

commanders held an important meeting. A few days later, on April 14, the

Mujibnagar government officially declared a structure of the Bangladesh

liberation force, naming it Muktifouj under the command of Colonel MAG

Osmani.9 However, it was not before the middle of July 1971 that the Mukti

Bahini was formally organised, through a conference of senior Bengali

officers arranged by the Mujibnagar government. This conference dealt

with vital issues like creation of war sectors, demarcation of sector

boundaries, organising the guerrilla and regular forces, formulating war

strategy and tactics. It was decided to divide Bangladesh into 11 sectors

and 69 sub-sectors in order to consolidate war efforts. In addition to that,

3 independent brigades were to be created, namely K Force under Major

Khaled Musharraf, S Force under Maj. K.M. Safiullah and Z Force under

Maj. Ziaur Rahman.10

The total number of fighters available at the moment included about

18,000 regular forces (made up of EPR, EBR and Police forces), about 150

officers and around 130,000 guerrillas.11 In addition to that, there were

7

ASIAN AFFAIRS

many independent forces of guerrillas, who organised resistance under

their own leadership. Most prominent among such forces were Kader

Bahini (forces commanded by Kader Siddiki, also known as Tiger Siddiki,

from Tangail), consisting of about 17,000 fighters, Afsar Battalion

consisting of 4,500 fighters and Hemayet Bahini with about 5,000

fighters. 12 There were also other smaller forces organised by local

initiative. Some leftist organisations, including the Communist Party of

Bangladesh (CPB) and others developed their own guerrilla forces.

Independent of all the forces mentioned above was the Bangladesh

Liberation Forces (BLF), popularly known as Mujib Bahini. This force,

numbering about 5000, was mainly drawn from the Awami League and its

student front Chhatra League, and was trained under the direct supervision

of Major General Uban of Indian Army at Deradun hills.13 The formation

and training of Mujib Bahini took place against the wish of the Bangladesh

government authorities, which led to a conflict situation between the

two.14 However, Mujib Bahini remained a part of the broader liberation forces

and fought against the common enemy until the liberation of Bangladesh.

Pakistani views on Mukti Bahini

The general opinion about MB among Pakistani military officers and

policymakers was obviously hostile, since these were the forces that they

had tried so hard to eliminate. They looked upon MB merely as Indian

stooges, who were no match for the mighty Pakistan army. In addition to

that, a tendency to underrate the MB and their activities is also clearly

visible among them. At the same time, there are certain subtle differences

of opinion among the Pakistani authors regarding the role of Bengali

Freedom Fighters.

Some Pakistani authors including Major General A.O. Mitha, who

served as the Deputy Corps Commander of Pakistan army in occupied

Bangladesh in 1971, Brigadier (Retd.) Z.A. Khan, who earned his fame by

arresting Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on the night of 25th March 1971, Major

General Hakeem Arshad Qureshi and others, who commanded a Pakistani

battalion in occupied Bangladesh, treat Mukti Bahini with pronounced

disdain in their respective autobiographies. Z.A. Khan, for instance,

mentions the name Mukti Bahini only twice in his 400-page book on

his military career, and prefers to call Bengali freedom fighters rebels15.

But even he indirectly admits the effects of MB activities on his fellow

soldiers, when he writes: in this period (e.g. June-July 1971 author)

army officers would not move around the city (of Dhaka author) without

8

MUKTI BAHINI AND THE LIBERATION WAR OF BANGLADESH

an escort, each officer would have at least three or four men in his vehicle,

there was no movement after dusk.16

To General A.O. Mitha, MB was merely an extension of the Indian

forces, which could have been dealt with properly had Pakistani military

adopted an appropriate strategy under a more capable leadership. In his

autobiography, Mitha hardly tries to conceal his despise for the Bengalis.

But even he recognises the hard reality: once it was clear that the

majority of East Pakistanis no longer wanted to be a part of Pakistan, there

was no sense in continuing to fight except to be able to surrender on

honourable terms.17

General H.A. Qureshis account of the war has been written in the

same line18. As far as he is concerned, the war was fought between

Pakistan and India, where the MB just supplemented the Indian forces.

Qureshi is also convinced that there were a substantial number of Indian

and army personnel in the garb of Mukti Bahini guerrillas19.

Similar views have been expressed by another retired Pakistani

General % Kamal Matinuddin. He admits the increasingly active role

played by the MB in 1971, but claims that the effectiveness of the Mukti

Bahini was grossly overestimated to build up their own morale, lower that

of the Pakistan Army and gain more international support.20 Matinuddin

asserts that such lack of effectiveness of the MB was due to the fact that

it was not sufficiently trained to fight regular battles, that the Bengali

freedom fighters were mostly trained for insurgency operations.21 But

then, quoting some Indian sources, Matinuddin hints at the racial

superiority of the Pakistani martial race by stating that the Bengalis

were mortally afraid of Pathans and Punjabis and would not confront then

in the battlefield.22 He sees the main contribution of MB in providing

updated information about Pakistan army locations and strength, and

concludes that by itself the Mukti Bahini would not have been able to

liberate Bangladesh23.

ASIAN AFFAIRS

However, he is convinced that many Indian regular troops operated in

the guise of Mukti Bahini. As proof for his contention, Niazi cites the

explosion at Hotel Intercontinental in Dhaka and the destruction of bridges,

which he claims could not have been done by Bengali Guerrillas26.

Curiously, Niazi blames Indian press for understating the role of MB.

His contention is that India exaggerated the successes of MB before the

Indo-Pak war started, but in actual war, they tried to play down the

achievements of Mukti Bahini This was an attempt to belittle the role

of Mukti Bahini in order to glorify the Indian Army and give all the credit

to Indian troops27. Niazis resentment against Indians is not surprising,

since he holds India and USSR responsible for instigating the liberation

war of Bangladesh: if the Indians and the Russians had not helped the

Bengalis they would have never dared to revolt against the centre28. In

any case, one may perceive such statement as an indirect way of

acknowledging that the MB did have impressive achievements.

Nevertheless, Niazis despise for MB was strongly reflected in his initial

strong resistance to surrender to the joint forces of India and Bangladesh29.

Major General (Rtd.) Rao Farman Ali, who was Niazis opponent in the

Pakistani occupation army in Bangladesh, also has a curious theory about

Indian intentions with regard to Mukti Bahini. He asserts that the Indians

saw MB as their ultimate enemies because they would oppose Indian

domination in future. Hence, the Indians wanted to weaken the MB by

sending them on short offensive operations against Pakistan Army. As a

result, Both MB and Pakistan Army (both of whom were Muslim, reminds

Rao) were seriously affected30. However, General Rao does not explain

whether the indiscriminate genocide of Bengalis by their Pakistani

Muslim brethren was also instigated by India. It is also relevant to

mention that Rao, just like Niazi, opposed the idea of the Pakistan Army

surrendering to the Indo-Bangladesh joint forces % he insisted that the

words Mukti Bahini be deleted from the instrument of surrender31.

General AAK Niazi, who served as the commander of Pakistani

occupation forces in Bangladesh during the war, shows slightly different

perception of the Mukti Bahini from the other Pakistanis mentioned above.

He acknowledges the fact that the MB was gradually growing stronger both

in terms of military training as well as morale24. He also admits the impact

of MB operations on the Pakistan army, when he laments that his forces

were taking casualties without fighting on account of Mukti Bahinis

guerrilla activities, which was adding to the strain on the proud army25.

This brief survey of the attitude of Pakistan Army commanders

regarding Mukti Bahini clearly shows how biased it was. On the one hand,

they admit, directly or indirectly, the serious effects of Mukti Bahini

operations, on the other hand they do not want to give MB the credit for it.

They would rather blame the Indian Army for acting in the guise of Mukti

Bahini, because that would save them the disgrace of admitting

casualties at the hands of Mukti Bahini. They did not want the name of

Mukti Bahini to be mentioned in the instrument of surrender for the

same reason; it would be a shame for the mighty Pakistan Army to

10

MUKTI BAHINI AND THE LIBERATION WAR OF BANGLADESH

ASIAN AFFAIRS

surrender to the army of Bengalis, whom the Pakistani military leaders

had got accustomed to treat as racially inferior black bastards32.

relevant to quote Siddiq Salik, the then Public Relations Officer (PRO) of

Pakistan Army in occupied Bangladesh, regarding the matter:

From the beginning of Pakistani military crackdown on Bangladesh

till the end of the war, there was not a single day when the Mukti Bahini

did not carry out offensive operations against Pakistan Army33. These

actions were carried out by the young fighters of Mukti Bahini, not Indian

soldiers. Until the latter half of November 1971, the Indian Army or even

the Indian Border Security Force (BSF) did not take part in active part in

hostilities except providing training, weapons and logistic facilities to MB.

All guerrilla operations in occupied Bangladesh were conducted by

Bengalis, not Indians, though most of those Bengali guerrillas were trained

and armed by Indians. For example, the attack on Hotel Inter Continental

mentioned by Niazi, was carried out by a dedicated group of young guerrillas,

all of whom were students from Dhaka34.

Travelling from Dacca and its suburbs towards the interior, one could

not help feeling that one was passing through an enemy area. It was

impossible to move without a personal escort which, in turn, served as

a provocation for the rebels. They ambushed the party or mined its

path. If one reached ones destination safely, one could look back on

the journey as a positive achievement36.

Another point that needs to be addressed in this connection is the

fear of Pathans and Punjabis among the Bengalis that Pakistani Generals

are so fond of narrating. There is no doubt that ordinary Bengalis were

afraid of Pakistani soldiers, whether they were Pathans, Punjabis or

Sindhis. If they were not, ten million people would not have fled from

occupied Bangladesh and sought shelter in India. The reasons for such

fear are well known. There are many accounts from independent sources

of the atrocities committed by Pakistani forces at that time. One of the

most horrifying descriptions of Pakistani brutalities has been recorded by

Anthony Mascarenhas, former Assistant Editor of Daily Morning News,

published from Karachi. Mascarenhas visited Bangladesh in the middle

of 1971 and had the opportunity of watching Pakistan Army actions from

close quarters. Afterwards, he fled to London and published a story in the

Sunday Times, London, on genocide in Bangladesh. In it, Mascarenhas

gives details of the casual way in which ordinary Bengali people were

killed, tortured and humiliated by Pakistani soldiers and officers. All these

crimes against humanity were carried out under such code names as

cleansing process, sorting out and punitive operations35. It was this

barbarity of Pakistani soldiers that made the Bengalis fear and hate them,

not their superior racial quality.

But once the timid Bengalis received the basic minimum training,

arms and ammunition, they started striking back at their tormentors. By

October 1971, the Mukti Bahini became so strong that even the mighty

Pathans and Punjabis began to fear them. To prove this point, it would be

11

The same Bengalis, who used to be so afraid of the Pakistanis at the

beginning of the war, had now acquired the skill and power to restrict the

movements of their enemy%now it was the turn of the tormentor to be

afraid of its victim.

The Indian perspective

The Indian view of MB was essentially different from the Pakistani

perspective. When millions of distressed Bangladeshis fled from occupied

Bangladesh, India was faced with the huge problem of providing them with

food, shelter and other essentials. In addition to the refugees, there were

members of Bengali armed forces and thousands of young people who

wanted military training, arms and ammunition. In this background,

Mukti Bahini grew and developed in close cooperation with Indian armed

forces. Naturally, there is a much better understanding of MB among Indian

military and political leaders.

Lt. General (Retd.) JFR Jacob, Chief of Staff of Indias Eastern Army

during the Bangladesh War of Liberation in 1971, gives a brief but precise

assessment of the strength and weaknesses of the Mukti Bahini, and of

the role that it played in his book on the war37. Jacob explains that a large

number of guerrillas had to be trained within the short period of three to

four weeks, which had an adverse effect on the performance of MB. Besides,

there was a shortage of proper leaders among the freedom fighters, as

many young people who could be utilised as guerrilla leaders were absorbed

by the regular forces. Jacob believes that had this manpower and

leadership been utilized to make up hard-core guerrilla forces they would

have achieved much better results38. Nevertheless, Jacob duly recognises

the achievements of MB. This is how he summarises their effectiveness:

Despite the limitations of training and lack of junior leadership, they

(e.g.Mukti Bahini - author) contributed substantially to the defeat of

Pakistani forces in East BengalThey completely demoralized the

12

MUKTI BAHINI AND THE LIBERATION WAR OF BANGLADESH

Pakistani Army, lowering their morale and creating such a hostile

environment that their ability to operate was restricted and they were

virtually confined to their fortified locations. The overall achievements

of the Mukti Bahini and the East Bengal Regiments were enormous

Their contribution was a crucial element in the operations prior and

during full scale hostilities.39

Similar assessment of MB has also been made by Major General (Retd.)

D.K. Palit of Indian Army. Commenting on the enthusiastic support given

by Mukti Bahini to the Indian Army, Palit states that the support and

cooperation supplied by the guerrillas was remarkable. The elements of

the Bahini trained and equipped to fight as regular infantry were, in view

of the short preparatory period, not as operationally significant as the vast

number of guerrilla groups that acted as eyes and ears for the advancing

forces40. Palit also emphasizes the impact of MB operations on the

Pakistani forces:

Senior commanders among the Pakistani prisoners of war have since

confirmed that the Mukti Bahini guerrillas so controlled the countryside

that very little night movement could be undertaken outside the

cantonments and fortresses. In most areas only daytime patrols were

carried out % and then only in large bodies.41

At the same time, Palit points out some of the weaknesses of

Bangladeshs struggle for liberation. He particularly blames the political

leadership of Bangladesh for failing to organise the future resistance forces

in time. He laments that after the nation stirring events that followed

the Declaration of February 12, and even more so after March 1st, there

still was no effort to establish a coordinated resistance plan with officers

of the armed forces42.

Major General Sukhwant Singh, another Indian commander, is not so

enthusiastic about MB. Without understating the contributions of the

Mukti Bahini, Singh asserts that the hope of a solution through Mukti

Bahini had receded, for it was apparent that it would take such a movement

years to unloosen the military stranglehold on Bangladesh43 However,

Singh also acknowledges that the initial Mukti Bahini operations helped

the Indian Army, which got to know the Pakistani pattern and concept of

fighting44.

The most comprehensive study of the Indian views on the Mukti Bahini

has perhaps been done by Captain (Retd.) S.K. Garg in his book titled

Freedom Fighters of Bangladesh. Beginning with the theoretical

13

ASIAN AFFAIRS

framework and practical aspects of modern guerrilla warfare, Garg

examines the performance of MB in the Bangladesh war of liberation. He

highlights the effects that were made by the guerilla activities of the MB,

pointing out that, As days went by, the Mukti Bahini expanded the scope

and frequency of its hit-and run raids, ambushes and attacks on small

isolated enemy positions which resulted in liberating the occupied

territory45. Quoting a senior Indian Army officer, who conceded that

the support of the Mukti Bahini might have made a difference of two

more weeks, Garg maintains that during a war of only 14 days, the

difference of two weeks amounts to the total contribution made by Indias

Defence Forces to the liberation struggle of Bangladesh, that too at such a

crucial moment when time was a vital factor46.

Contrary to that, Garg also refers to other Indian Army officers who

expressed doubts about the efficacy of the Mukti Bahini. According to these

critics, by itself, the Mukti Bahini was not competent to liberate

Bangladesh and without the physical intervention of Indias Defence

Forces, Bangladeshs struggle for liberation would have been inordinately

delayed or even degenerated into a Vietnam type of war with an

unpredictable outcome47. Based on personal experience, some of these

officers had formed rather low opinion of the Bangladeshi freedom fighters,

and believed that the inexperienced, poorly trained and inadequately armed

Mukti Bahini was no match for brutally-ruthless and well oiled Pakistani

war machine. Some officers, according to Garg, also claimed that Bengali

freedom fighters were reluctant to confront the khaki-outfitted Pakistani

soldier.

However, Garg hastens to add that those adverse opinions about Mukti

Bahini are mainly concerned with irregular guerrillas, whose low

intensity operations, during a regular war, are naturally relegated into

the background, due to the high intensity of regular operations.

Nevertheless, concludes Garg, It would be unfair to assume that the Mukti

Bahini remained totally ineffective. In one or two sectors they might have

been less successful as pointed out by some Indian officers; but, by and

large, they did more than anyone had expected them to do.The regular

guerrillas were certainly much more effective than their counterpart %

the irregular guerrillas48.

Although such conclusion drawn by Garg appears to be balanced, it

has a tendency of generalising the weaknesses and ineffectiveness of

the irregular guerrillas of the Mukti Bahini. Guerrillas who were given a

hasty two-week long training could not be a match for experienced Pakistani

14

MUKTI BAHINI AND THE LIBERATION WAR OF BANGLADESH

soldiers. Similarly, those guerrilla groups which lacked appropriate

leadership also could not perform up to the mark. Books have been written

by former members of the Mukti Bahini, which describe the way in which

the guerrilla movement was born and matured. For example, Guerrilla

Theke Sommukh Juddhe (From a Guerrilla to the frontal fight), a war

time reminiscence, narrates with intricate details about how a group of

Bangladeshi young man from different walks of life was transformed from

an ordinary, non-violent student into tough guerrilla fighters in order to

save the life and honour of their fellow countrymen49. Kader Siddiki, the

renowned freedom fighter from Tangail, also narrates details of formation

and operations of his guerrilla forces that constantly harassed the Pakistan

Army in the area50. These and many other books written by former Mukti

Bahini members show the readers the great sacrifice that the Mukti

Bahini had made in 1971 to liberate from Pakistani occupation.

Concluding Observations

The Bangladesh war of Liberation was a multi-dimensional event of

great importance. First and foremost, it was a struggle waged by the people

of Bangladesh to achieve independence. Secondly, as India supported the

cause of Bangladesh, this struggle was translated into a regional rivalry

between India and Pakistan. Finally, in the Cold War perspective, the

struggle also triggered a triangular international power game between

USA, USSR and China. In this larger international and regional canvass,

the Mukti Bahini of Bangladesh is not always seen in the appropriate

perspective. The Indo-Pakistan War of December 1971, which was the

culminating point of Bangladesh Liberation War, tends to overshadow the

slow and painstaking but effective struggle that Mukti Bahini had waged

against the occupation army of Pakistan for preceding nine months.

Whether or not Mukti Bahini could liberate Bangladesh on its own is a

mere academic question, since India, burdened with the problem of 10

million Bangladeshi refugees, was in no position to wait for that. The

government and the people of Bangladesh also preferred a quicker end to

their agony. The Mukti Bahini did what it could, and history shows that

its performance not only made life miserable for the Pakistan Army, but

also paved the way for a speedy Indian victory. That is why for the people of

Bangladesh, Muktijoddha (freedom fighter) and Muktijuddho (liberation

war) are connected inseparably.

ASIAN AFFAIRS

References

1

2

3

Cited in: Rafiqul Islam, A Tale of Millions, Anonnya, Dhaka, 2005, p.82

Ibid.

Interview, Maj. Gen (Retd.) Shafiullah, Bangladesher Swadhinota Juddho:

Dalilpatra (henceforth Dalilpatra), Vol. 9, Dhaka, 1984, p.253

Kamal Matinuddin (Retd.Lt. General), Tragedy of Errors, Wajidalis (PVT)

Ltd., Lahore, Pakistan, 1994, p. 225

See: Revisiting 1971 % Discussions between Air Vice-Marshall (Retd.)

A.K. Khondokar, Wing Commander (Retd.) S.R. Mirza and Moyeedul

Hassan, Daily Prothom Alo, Dhaka, Victory Day issue, December 16, 2008,

pp. 4-5).

For details, see: Rafiqul Islam, op. cit,, pp. 96-128

Interview, Major General (Retd.) Shafiullah, Dalilpatra, op. cit., pp.221275

Such was the case in Rangpur and Syedpur Cantonments. See for

details: Major (Retd.) Nasir Uddin Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, Agamee

Prakashani, Dhaka, 2005, pp. 114-120

Afsan Chowdhury, Bangladesh 1971, , Mowla Brothers, 2007, vol. 2,

pp.141-142

Mir Shawkat Ali (Retd.Lt-Gen), The Evidence, Vol.2, Somoy Prakashani,

Dhaka, 2008, pp.31-38

Rafiqul Islam, op.cit, pp. 238-241

Dalilpatra, op.cit., p.637-676

Sirajul Islam ed., Banglapedia (National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh),

Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, 2003, pp.111-112

For details, see: Moyeedul Hassan, Muldhara Ekattur,University Press

Limited, Dhaka, 1995, pp.71-74

Z.A. Khan (Retd. Brigadier), The Way It Was, DYNAVIS (Pvt.) Ltd.,

Karachi, Pkistan,1998, pp. 262-319

Ibid, p.318

A.O. Mitha (Retd. Major General), Unlikely Beginnings: A Soldiers Life,

Oxford University Press, Karachi, Pakistan, 2003, p.365

Hakim Arshad Quereshi (Retd. Major General), The 1971 Indo-Pak War: A

Soldiers Narrative, Oxford University Press, Karachi, 2002

Ibid.,p.287

Kamal Matinuddin, op.cit. p.236

Ibid., p.237

Ibid.

Ibid, p.238.

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

15

A.A.K. Niazi (Retd. Lt.-General), The Betrayal of East Pakistan,

Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1998, pp.73-74

Ibid., p.100

Ibid., p.75

16

MUKTI BAHINI AND THE LIBERATION WAR OF BANGLADESH

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

Ibid., p.75

Ibid., p.74

Ibid., p.232

Rao Farman Ali Khan (Rtd. Major General), Bangladesher Jonmo

(Bengali translation of Pakistan Got Divided), University Press

Limited, Dhaka, 1996, p.101

Ibid., p.157

Siddiq Salik (Retd. Major), Witness To Surrender, The University

Press Limited, Dhaka, 1997, p.29

For a day-to-day narration of MB military operations from May to

December, see: Afsan Chowdhury, op.cit, pp.199-434

Details about this and other Dhaka operations by Mukti Bahini

have been documented by Habibul Alam, a valiant freedom fighter

in his book Brave of Heart, Academic Press and Publishers Library,

Dhaka, 2006

Anthony Mascarenhas, Genocide, Sunday Times, London, June

13, 1971, reprinted in ed. Sheelendra Kumar Singh, et al, ed.,

Bangladesh Documents, Vol.1,, The University Press Limited,

Dhaka, 1999, pp.358-373

Siddiq Salik, op.cit.,p.115

JFR Jacob (Retd. Lt. Gen.), Surrender at Dacca: Birth of a Nation, The

University Press Limited, Dhaka, 1997

Ibid.p.93

Ibid.p.94

D.K. Palit (Retd. Major General), The Lightning Campaign: The IndoPakistan War 1971, Thomson Press Limited, New Delhi, 1972,

p.154

Ibid., p.155

Ibid., p.52

Sukhwant Singh (Retd. Major General), Indias Wars Since

Independence: the Liberation of Bangladesh, Vol.1, Nawroze

Kitabistan, Dacca, 1980, p.106

Ibid., p.128

S.K. Garg (Retd. Captain), Spotlight: Freedom Fighters of Bangladesh,

Academic Publishers, Dhaka, 1984, p.130

Ibid.,p.137

Ibid.,p.136

Ibid.,p.143

Mahbub Alam, Guerrilla Theke Sommukh Juddhe, Sahittya Prakash,

Dhaka, 1999

See: Qader Siddiki, Swadhinata 71, Ononnya, 1997

17

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Pakistan ArmyDokument9 SeitenPakistan Armyumair aliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistan ArmyDokument34 SeitenPakistan ArmyHashim Mahmood Khawaja100% (1)

- The Pakistan Army From 1965 To 1971Dokument25 SeitenThe Pakistan Army From 1965 To 1971David Prada García100% (1)

- Major General Zia Ul Haq Nur, Punjab Regiment-ObituaryDokument31 SeitenMajor General Zia Ul Haq Nur, Punjab Regiment-ObituaryStrategicus PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defence Day SpeechDokument4 SeitenDefence Day SpeechHussain Mehdi100% (2)

- Fall of DhakaDokument4 SeitenFall of Dhakaapi-3813241100% (4)

- Pakistan ArmyDokument33 SeitenPakistan ArmyOmair AslamNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is The Difference Between A Resume and A CVDokument1 SeiteWhat Is The Difference Between A Resume and A CVapi-233727506100% (1)

- 3 - Kargil War CompaignDokument166 Seiten3 - Kargil War Compaignsourabhbadhani7Noch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Punjab in 1965 WarDokument16 Seiten4 Punjab in 1965 WarStrategicus PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistan ArmyDokument91 SeitenPakistan ArmyRehan TahirNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 Baluch The Battalion Which Captured PanduDokument39 Seiten11 Baluch The Battalion Which Captured PanduStrategicus PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slide Show On Kargil WarDokument35 SeitenSlide Show On Kargil WarZamurrad Awan63% (8)

- Major A. M. Sloan Martyr in Kashmir 1948 WarDokument4 SeitenMajor A. M. Sloan Martyr in Kashmir 1948 WarAhmad Ali MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistan Army's First Warlord Who Led Its Longest War - General Douglas Gracey and The Kashmir War of 1947-48Dokument118 SeitenPakistan Army's First Warlord Who Led Its Longest War - General Douglas Gracey and The Kashmir War of 1947-48Strategicus PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kargil WarDokument35 SeitenKargil Warsachin100% (1)

- Pakistan's Strategic Environment Post 2014Dokument256 SeitenPakistan's Strategic Environment Post 2014SalmanRNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pak Bibliography PDFDokument587 SeitenPak Bibliography PDFZia Ur RehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- David McclellandDokument2 SeitenDavid McclellandJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muktibahini Wins Victory - Maj Gen ATM Abdul Wahab 365pDokument365 SeitenMuktibahini Wins Victory - Maj Gen ATM Abdul Wahab 365pMSKCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exam Preparation New-1Dokument226 SeitenExam Preparation New-1Usman NiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistan Army in KashmirDokument80 SeitenPakistan Army in KashmirStrategicus PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Afghanistan Natural Gas Development ProjectDokument19 SeitenAfghanistan Natural Gas Development ProjectStrategicus PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangladesh Documents 1971 A.S.M Shamsul Arefin Part 1234 Combined PDFDokument2.205 SeitenBangladesh Documents 1971 A.S.M Shamsul Arefin Part 1234 Combined PDFSaikotkhan0Noch keine Bewertungen

- Majeed Brigade: TBP Feature ReportDokument42 SeitenMajeed Brigade: TBP Feature ReportnasserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Battle of JamalpurDokument24 SeitenBattle of Jamalpurjuliusbd46100% (2)

- Bangladesh Military Academy Military History Battle of KamalpurDokument6 SeitenBangladesh Military Academy Military History Battle of KamalpuroctanbirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete Book PDFDokument92 SeitenComplete Book PDFMd.Azimul IslamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Structure of The Pakistan ArmyDokument14 SeitenStructure of The Pakistan ArmyChudhary waseem asgharNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical Evaluation of Icj Report On Bangladesh GenocideDokument23 SeitenA Critical Evaluation of Icj Report On Bangladesh GenocideAwami Brutality67% (3)

- 3ui (,::,') Il"'Jti::" HB /$Mhw::Rfi!O .,O,": 3mi ( (I:1I'""'J'"" K//) Hffhi"'"0 E'ODokument12 Seiten3ui (,::,') Il"'Jti::" HB /$Mhw::Rfi!O .,O,": 3mi ( (I:1I'""'J'"" K//) Hffhi"'"0 E'OMumtazAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistan Army Motto:-: OfficersDokument25 SeitenPakistan Army Motto:-: OfficersUbaidUllahraaifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anatomy of Violence - Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan N 1971Dokument16 SeitenAnatomy of Violence - Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan N 1971Rage EzekielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henderson Brooks - Bhagat ReportDokument4 SeitenHenderson Brooks - Bhagat ReportGopinath PothugantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tormenting Seventy OneDokument122 SeitenTormenting Seventy OneSk. Md. Saifur Rahaman100% (3)

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 - Wikipedia PDFDokument197 SeitenIndo-Pakistani War of 1965 - Wikipedia PDFAbdul QudoosNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critique of Sarmila Bose's Book Absolving Pakistan of Its War Crimes in The 1971 Genocide in BangladeshDokument13 SeitenA Critique of Sarmila Bose's Book Absolving Pakistan of Its War Crimes in The 1971 Genocide in BangladeshTarek FatahNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitledDokument37 SeitenUntitledapi-224886503Noch keine Bewertungen

- Book Review - The Monsoon War Young Officers Reminisce - 1965 India Pak WarDokument11 SeitenBook Review - The Monsoon War Young Officers Reminisce - 1965 India Pak War17czwNoch keine Bewertungen

- GK - Pakistan Army PDFDokument9 SeitenGK - Pakistan Army PDFRana Bilal100% (2)

- Pakistan Army - Wikipedia PDFDokument173 SeitenPakistan Army - Wikipedia PDFAreeb AkhtarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On Shah Ahmad NoraniDokument253 SeitenResearch Paper On Shah Ahmad NoraniAli RazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great TragedyDokument79 SeitenThe Great TragedySani Panhwar100% (2)

- Nur KhanDokument11 SeitenNur KhanTalha Waqas100% (1)

- PMA Initial InterviewDokument155 SeitenPMA Initial Interviewwaseem0379100% (4)

- List of Army OfficersDokument9 SeitenList of Army Officersshahid asgharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cordesman Pakistan WebDokument218 SeitenCordesman Pakistan WebnasserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Review: 1. About The Author - Author of The Book Was LT Gen Agha Ali Ibrahim AkramDokument4 SeitenBook Review: 1. About The Author - Author of The Book Was LT Gen Agha Ali Ibrahim AkramMunazzagulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakis Army - Doctrne PDFDokument69 SeitenPakis Army - Doctrne PDFRida0% (1)

- 1971 Pakistan-India War: Battle of ShakargarhDokument32 Seiten1971 Pakistan-India War: Battle of ShakargarhAmir Qureshi100% (3)

- HRM ArmyDokument25 SeitenHRM Armyshringimahesh0% (1)

- Pakistan DefenceDokument74 SeitenPakistan DefenceSyedAamirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Siachen Hero Bana SinghDokument5 SeitenSiachen Hero Bana SinghRamesh Lalwani100% (2)

- 19th Battalion Frontier Force - Piffer TigersDokument16 Seiten19th Battalion Frontier Force - Piffer TigersFrontier ManNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emergence of PakistanDokument3 SeitenThe Emergence of PakistanHadee Saber33% (3)

- State Versus Nations in Pakistan by Ashok BehuriaDokument129 SeitenState Versus Nations in Pakistan by Ashok Behuriasanghamitrab100% (1)

- Qmo DLP PDFDokument155 SeitenQmo DLP PDFdbhole234Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gen. Tikka KhanDokument15 SeitenGen. Tikka KhanHassun Cheema100% (1)

- Claws 2009Dokument282 SeitenClaws 2009samar79Noch keine Bewertungen

- Major Khairul Nizam Taib Rmaf CV PDFDokument7 SeitenMajor Khairul Nizam Taib Rmaf CV PDFKhairul nizam TaibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangladesh Military Academy Military History Pakistan Defence PlanDokument5 SeitenBangladesh Military Academy Military History Pakistan Defence PlanoctanbirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Production & Marketing: Production in Small BusinessDokument7 SeitenProduction & Marketing: Production in Small BusinessJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bengali Nationalism and Anti-Ayub Movement A Study of The Role of SyudentsDokument14 SeitenBengali Nationalism and Anti-Ayub Movement A Study of The Role of SyudentsJobaiyer Alam0% (1)

- Current Ratio: CommentsDokument8 SeitenCurrent Ratio: CommentsJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Square PharmaDokument2 SeitenSquare PharmaJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Districts of BangladeshDokument7 SeitenDistricts of BangladeshJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction NEEDDokument8 SeitenIntroduction NEEDJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Women Entrepreneurship in BangladeshDokument14 SeitenWomen Entrepreneurship in BangladeshSujon JonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Web Marketing Mix 4SDokument4 SeitenWeb Marketing Mix 4SJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Holistic Marketing Concept Is Based On The DevelopmentDokument5 SeitenThe Holistic Marketing Concept Is Based On The DevelopmentJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRM Practices in GPDokument8 SeitenHRM Practices in GPJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Difference Between A Curriculum Vitae and A ResumeDokument2 SeitenDifference Between A Curriculum Vitae and A ResumeJobaiyer AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liaquat Ali KhanDokument2 SeitenLiaquat Ali KhanHashir UsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political Map of PakistanDokument1 SeitePolitical Map of PakistanFarooq BhuttaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raymond Allen Davis Is CIA AgentDokument2 SeitenRaymond Allen Davis Is CIA AgentDr. Hussain NaqviNoch keine Bewertungen

- The State of Domestic Commerce in Pakistan Study 10 - Synthesis ReportDokument58 SeitenThe State of Domestic Commerce in Pakistan Study 10 - Synthesis ReportInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abcd Efg Hi JKDokument9 SeitenAbcd Efg Hi JKAnonymous 4lpzL7amtNoch keine Bewertungen

- B. Laila Khan: Read More Details About This MCQDokument229 SeitenB. Laila Khan: Read More Details About This MCQMuhammad SajedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tehsil Sports Officer 40 H 2017Dokument3 SeitenTehsil Sports Officer 40 H 2017Arshad Nawaz JappaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Standing Committee of Senate: (Chairperson)Dokument4 SeitenStanding Committee of Senate: (Chairperson)Azhar RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wa0005.Dokument2 SeitenWa0005.areegzulfiqar1256Noch keine Bewertungen

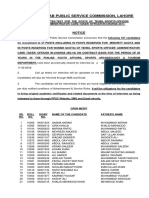

- Punjab Public Service Commission, Lahore: NoticeDokument5 SeitenPunjab Public Service Commission, Lahore: Noticeجنید سلیم چوہدریNoch keine Bewertungen

- Md. Ahanaf Thamid 1912802630Dokument13 SeitenMd. Ahanaf Thamid 1912802630Ahanaf FaminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Address FinalDokument6 SeitenAddress FinalZohaib BilalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Panama Case by UASDokument5 SeitenPanama Case by UASUmair AshrafNoch keine Bewertungen

- DCs Order - 240305 - 133442Dokument1 SeiteDCs Order - 240305 - 133442Nadeem AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- PCP Complaints Slides 09-09-2022Dokument5 SeitenPCP Complaints Slides 09-09-2022faizy216Noch keine Bewertungen

- Federal Estacode (Vol-I & II)Dokument1.204 SeitenFederal Estacode (Vol-I & II)Faheem Mirza100% (4)

- Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto As A Lawyer/Politician: Presented by Javeria Daud NarejoDokument8 SeitenZulfiqar Ali Bhutto As A Lawyer/Politician: Presented by Javeria Daud NarejoJaveria DaudNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 Role of Elites in PakistanDokument7 Seiten03 Role of Elites in Pakistanmudassir rehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistan History TimelineDokument4 SeitenPakistan History TimelinejaweriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gen. Tikka KhanDokument15 SeitenGen. Tikka KhanHassun Cheema100% (1)

- Cat-III GWLDokument242 SeitenCat-III GWLAmeen IslamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Result Gazette Hssc-II 2017 ADokument827 SeitenResult Gazette Hssc-II 2017 AMuhammad MumtazNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 To 30 SepDokument6 Seiten1 To 30 Sepak4abdullahkhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Age 65Dokument48 SeitenSupreme Court Age 65AttaNoch keine Bewertungen

- List PD Ips 26-28 18Dokument5 SeitenList PD Ips 26-28 18Mansoor Ul Hassan SiddiquiNoch keine Bewertungen

- FSC Decision On House RentDokument41 SeitenFSC Decision On House RentRaza VirkNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Leaf From HistoryDokument3 SeitenA Leaf From HistoryaghashabeerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Branch Updated List-1Dokument8 SeitenBranch Updated List-1Bestie VideosNoch keine Bewertungen