Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Giocoli - Presentation EUI

Hochgeladen von

ngiocoliCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Giocoli - Presentation EUI

Hochgeladen von

ngiocoliCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

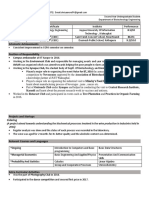

Old Lady charm:

explaining the persistent appeal

of Chicago antitrust

Nicola Giocoli

Department of Economics

University of Pisa

http://ssrn.com/author=92886

http://pisa.academia.edu/NicolaGiocoli

From classroom to courtroom

Traditional story: starting from end of 1970s, Chicago antitrust

law & economics (ALE) replaced old-style ALE (based on

structural approach, SCP), due to its theoretical superiority.

Chicago ALE as best example of the power of good economics to

migrate from classroom to policy- or court-room.

Assume this story is true. Today Post-Chicago approach (esp.

based on Bayesian game theory) offers a better answer to many

antitrust problems than Chicago. But

these answers are largely ignored by US antitrust courts.

My question is: how to explain Chicagos enduring success in US

courts? Why theoretical superiority isnt working this time?

An interesting episode to understand how, when and why

economic theories may influence policy- or law-makers.

How economists persuade as central issue for history of economics.

See Mankiw(2006) for similar story in macroeconomics.

What is Chicago antitrust?

Key Chicago ideas:

1950s/1960s price theory (esp. market theory)

Tight prior equilibrium (TPE) assumption

Sole value approach (antitrust law is economic policy)

Efficiency (= consumer/social welfare) as benchmark

Hospitality tradition wrt unusual business practices

Potential competition as trump card

Wrong convictions more harmful for welfare than wrong

acquittals (market will still find a way)

A set of ALE propositions/prescriptions descended from

these ideas. US courts at all levels endorsed them.

Examples: rejection of per se illegality rules; predatory pricing

doesnt exist; tying & RPM are pro-efficiency.

Post-Chicago ideas

Game-theoretic revolution in IO (since 1980s).

Push further characterization of agents strategic

rationality (see my previous works).

Game-theory shows that several business practices may

cause competitive harm.

Examples: predatory pricing; leverage theory of monopoly

profit; RRC paradigm

Even rescue some pre-Chicago per se prohibitions.

But... less than meager success in US courtrooms:

Just one Supreme Court precedent (Kodak 1992), totally

abandoned today;

A few lower courts applications (AMR 2003);

No Post-Chicago works quoted by federal courts (compare

scores of quotes from Chicago & Harvard).

Why the failure?

Many possible explanations

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

The real Chicago, or Your problem doesnt exist

Chicago never won (completely)

The power of (legal) status quo

The fairy tale, or Its the ideology, stupid!

Adam Smith knew it all

Long run vs short run effects (model selection problem)

Judges dont believe in fables

A matter of economic (il)literacy

On a level with dentists (Daubert/Twombly combo)

1. Your problem doesnt exist

New fad is to reduce Chicago ALE to a methodology, rather than a set

of positive and normative propositions (e.g. Wright 2012).

Chicago three methodological principles:

Price theory (taken as synonymous with neoclassical economics).

Commitment to empiricism.

Error cost framework.

Today every approach to ALE must (or should) obey these principles.

So it is not a matter of Chicago vs Post-Chicago anymore.

Two implications:

Chicago has won forever as far as ALE right method is concerned.

Chicago is still by far the approach providing the best empirical validation to

antitrust propositions. Chicago enduring success is empirically grounded. So my

problem doesnt exist because Post-Chicago is not superior, after all!

But this is not a proper picture of Chicago antitrust.

Chicago is not just a methodology (nor a bottom-up approach: think of TPE!).

Its empirical successes are few and over-valued (some were not even its own).

Price theory neoclassical economics.

Error cost analysis is premised on the market will still find a way principle.

2. The power of (legal) status quo

In late 1970s: weak status quo.

Warren Court antitrust was not really SCP; it was just Modern

Populism (= use ALE to pursue socio-political goals).

Easy game for Chicago: first real application of robust and

consistent antitrust law & economics.

In 2000s: powerful status quo.

Chicago is the new status quo.

Why do all the bounces go Chicagos way? (Crane 2009).

Post-Chicago answers are never clearly superior to dislodge

Chicago ones (Ties always go to the status quo).

Esp. because non-intervention is default rule for enforcers, if

aware of their own (and the laws) limits. See expl. #8.

3. Chicago never won (completely)

Two versions of this explanations:

3.1 Chicago never completely conquered US courts; resistance always

existed and still does.

3.2 Modern ALE is not 100% Chicago; it is the outcome of a HarvardChicago joint venture (Hovenkamp; Kovacic).

Both versions are questionable.

Against 3.1: same authors (= some Modern Populists) supporting it

today conceded defeat to Chicago back in 1980s!

Against 3.2: this is a very convincing, well-documented thesis. But

is it really a joint venture or a takeover (= Harvard surrender to

Chicago key ideas)?

Clear links here with expl. #1: We are all Chicagoans now.

Note: 3.2 may now include the Neo-Chicago variant (Evans &

Padilla 2005), i.e. modern ALE as a moderate version of Chicago.

But: look at Neo-Chicago key ideas. Is it a softer, gentler Chicago or a

Chicago squared? Or is it just a smart marketing label?

4. The fairy tale

Chicago triumph was not a matter of theoretical superiority, but

just the intended outcome of late 1970s early 1980s rise of

conservative ideology in American society.

Same story, with opposite enforcement pattern, during 1960s: the Warren

Court antitrust was equally ideological.

Chicago has a strong ideological belief in the superiority of market

solutions over State or judicial intervention.

Appointed judges and Justices share that belief, much like big business!

This explains both success & persistence of Chicago ALE: the right

approach & the right persons at the right time in the right places.

By demolishing the false certainties of Chicago approach without

gaining ground in courts, Post-Chicago highlights the role of

ideology in driving enforcement.

Normative beliefs in US (at least in many US courts) are still pro-market,

while Post-Chicago has no clear alternative ideology to offer.

Implicit idea: economics as just a veil covering normative values.

This explanation is strongly rejected by supporters of expl. #1.

5. Adam Smith knew it all

10

Classical view: competition as a process, which is promoted by

freedom of contract.

Neoclassical view: competition as a state, which warrants

freedom from market power.

The thesis: Chicago taught courts to view competition as a state

(static efficiency view). This made judges blind to the richer

dynamic implications of Post-Chicago approach.

But: history of economics contradicts this explanation!

It was Harvard SCP that brought static neoclassical view

(competition as a market structure) to ALE.

Basic SCP idea: use antitrust to engineer a competitive market.

At its core, Chicago rejects this idea: markets (with their

dynamics) always know better than judges or policy-makers!

Moreover, freedom of contract is more important for Chicago

than freedom from market power because it allows potential

competition to fully work its magic (again, a Classical idea).

6. Long run vs short run effects

11

Most business practices have opposite short run (SR) & long run

(LR) welfare effects. Economics cant really tell which is bigger.

Examples: predatory pricing; essential facilities; learning curve

When a given practice shows opposite SR & LR effects, law

enforcers must trespass theory and adopt normative evaluations.

Its a typical model selection problem, but with no empirical or theoretical

grounds to solve it. Economicss own limits force normativeness in.

Were back to ideology, but this time the ideological dispute is not

about any grand scheme of society. The normative choice is simply between

alternative economic models.

US courts side with Chicago principle: always trust the markets

ability to generate LR gains. Model selection is anti-intervention.

Post-Chicago: free markets do not warrant max welfare. Model

selection is pro-intervention.

This is also a normative premise of European competition policy. Hence EU

antitrust may be more receptive to Post-Chicago ideas.

7. Judges dont believe in fables

12

Generalizing vs exemplifying models (Fisher 1989).

Generalizing models: from broad assumptions to inevitable consequences; they

describe what must happen.

Exemplifying models: highly sensitive to specific assumptions; they describe

what may happen.

Chicago approach (often) employs generalizing models.

Post-Chicago models are always exemplifying ones. They just

describe possible worlds, where a certain business practice may be

anti-competitive.

In general, all game-theoretic models are fables (Rubinstein 2006)

Like fables, they typify & stylize a given situation; like fables, they (usually)

teach a lesson with universal validity, but no specific applicability.

Do judges believe in fables? Can they?

Note: some Chicago doctrines (e.g. free riding argument for RPM, single

monopoly profit theory for tying) fare quite well in US courts despite their

being more fable-like than Post-Chicago counterarguments.

13

8. A matter of economic (il)literacy

Administrability is key (Hovenkamp)

Law must be administrable, but judges lack the ability to handle

complicated theories. (Justice Breyer).

In the spirit of explanation 3.2, emphasis on administrability is

Harvard Law School main contribution to modern ALE (Kovacic).

Administrability as informal forerunner of Chicago error cost analysis.

Which approach is more administrable for real-world judges?

Chicago price theory is well-established, easy to understand & with

clear prescriptions/catchwords. Cant say the same of Post-Chicago!

Price theory is the kind of Economics 101 taught to would-be/present judges,

at least in the not-so-distant past (say, until the late 1980s).

How many active judges know how irrelevant Chicago price theory is for

contemporary industrial economics?

Perhaps the simplest explanation of Chicago success & resilience.

If this is true, things should change when & if we teach more Bayesian game

theory in law schools. Great news for economists, but

9. On a level with dentists

14

but for the Daubert + Twombly combo.

Daubert (1993): Supreme Courts two criteria for expert testimony

(say, by an economist) to be admitted in court.

Expert testimony must be relevant and reliable.

Relevant = based on the facts of the case.

Reliable = based on a scientific theory (where scientific means falsifiable &

widely accepted).

Does modern economics pass the Daubert test? What ALE approach

fares better? As a lawyer, what economist would you hire as expert?

Post-Chicago fails under both criteria: exemplifying models are hardly

falsifiable & with little relation to facts. Chicago generalizing models

have a big edge here (so they are most frequently used in courts).

Hardly a new issue: If economists could manage to get themselves

thought of as humble, competent people on a level with dentists,

that would be splendid (Keynes 1931).

Viz. a dentist would be admitted as expert testimony. What about economists?

Add Twombly (2007): dismiss private litigations if plaintiffs argument

lacks factual elements making it economically plausible.

Again, it is hard for Post-Chicago models to satisfy this requirement.

And the winner is

15

What is the best explanation? I dont know. Each captures a bit of the

story, but none is entirely convincing.

The reason of US antitrusts enduring fascination with Chicago is still

a secret like an Old Lady charm.

What I know is that all explanations highlight the difficulty (or

undesirability) of dislodging Chicago from US courtrooms.

Take explanation #6 (LR vs SR effects). Economists could/should

provide better measurements of these effects. This captures Chicago

call for more empirics, but good fact checking is difficult and costly.

Is there room for more empirical analysis in courtrooms?

Should antitrust institutions be re-designed to allow enforcers to make more

evidence-based model selection?

Or take explanation #8 (judges illiteracy). Again, an institutional way

out exists: either teach judges more modern economics, or, better,

create specialized antitrust courts.

But under explanations #7-9 (fables & dentists), that would fail too. Is

there room in adjudication for (possibly right) exemplifying theories

to prevail over (possibly wrong) generalizing ones? I doubt that.

Thank you!

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Introduction To Market Design.2011Dokument41 SeitenIntroduction To Market Design.2011ChrisRobyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice FTCE Reading General KnowledgeDokument17 SeitenPractice FTCE Reading General KnowledgeDeez NutsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dimensional Analysis, Scaling, and Zero-Intelligence Modeling For Financial MarketsDokument38 SeitenDimensional Analysis, Scaling, and Zero-Intelligence Modeling For Financial MarketsHmt NmslNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economists-Moral Philosopers: Adam Smith-The Wealth of Nations Karl Marx-Das KapitalDokument26 SeitenEconomists-Moral Philosopers: Adam Smith-The Wealth of Nations Karl Marx-Das KapitalDede MahendraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edgar Peters TalksDokument5 SeitenEdgar Peters TalksocalmaviliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economists-Moral Philosopers: Adam Smith-The Wealth of Nations Karl Marx-Das KapitalDokument26 SeitenEconomists-Moral Philosopers: Adam Smith-The Wealth of Nations Karl Marx-Das Kapitalvikas_ojha54706Noch keine Bewertungen

- 25 Theories To Get You StartedDokument8 Seiten25 Theories To Get You Startedshovon_iuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Computing Morality: A Computer Scientist's Approach Ethics and EconomicsVon EverandComputing Morality: A Computer Scientist's Approach Ethics and EconomicsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Random Walk Theory ExplainedDokument24 SeitenRandom Walk Theory ExplainedVaidyanathan RavichandranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Info 9the Great Divide Over Market Efficiency 1Dokument19 SeitenInfo 9the Great Divide Over Market Efficiency 1Baddam Goutham ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The SCP ParadigmDokument16 SeitenThe SCP ParadigmJambo MedfuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Let's Fix It!: Overcoming the Crisis in ManufacturingVon EverandLet's Fix It!: Overcoming the Crisis in ManufacturingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schumpeter's "Creative DestructionDokument4 SeitenSchumpeter's "Creative DestructionKristine May PadolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black ScholesDokument6 SeitenBlack ScholesMushtaq Hussain KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exam 2011 Questions and AnswersDokument7 SeitenExam 2011 Questions and AnswersLEWOYE BANTIENoch keine Bewertungen

- MacKenzie and Millo (2003)Dokument39 SeitenMacKenzie and Millo (2003)林陵Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1-1 2013 Introduction To BCADokument28 Seiten1-1 2013 Introduction To BCAsanhuo66Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bizsim The World of Business - in A Box: Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501, New Mexico, UsaDokument6 SeitenBizsim The World of Business - in A Box: Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501, New Mexico, UsapostscriptNoch keine Bewertungen

- 22.picker - Introgame 0Dokument25 Seiten22.picker - Introgame 0aurelio.arae713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Constructing Financial Markets: The Performativity of Option Pricing TheoryDokument39 SeitenConstructing Financial Markets: The Performativity of Option Pricing TheoryCaíque MeloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industrial EconomicsDokument41 SeitenIndustrial EconomicsLudovica la TorreNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Roemer - A Future For Socialism-Harvard University Press (1994)Dokument180 SeitenJohn Roemer - A Future For Socialism-Harvard University Press (1994)JoaquinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Government Regulation, Free Markets, and International TradeDokument20 SeitenGovernment Regulation, Free Markets, and International TradeMuhammad Bilal GulfrazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociology Project Introducing The Sociological Imagination 1st Edition Manza Test BankDokument22 SeitenSociology Project Introducing The Sociological Imagination 1st Edition Manza Test Banklyeliassh5100% (26)

- Capitalism K - Emory 2016Dokument23 SeitenCapitalism K - Emory 2016JoshFJNoch keine Bewertungen

- MicroEco PermidsemDokument238 SeitenMicroEco PermidsemNIKILNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ekonomi Bisnis Dan ManajerialDokument47 SeitenEkonomi Bisnis Dan ManajerialMaryam BurhanuddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law and Economics PostingDokument78 SeitenLaw and Economics Postingsirali94Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Tech Calls Thinking: An Inquiry into the Intellectual Bedrock of Silicon ValleyVon EverandWhat Tech Calls Thinking: An Inquiry into the Intellectual Bedrock of Silicon ValleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antitrust Exam ConsolidationDokument21 SeitenAntitrust Exam Consolidationmab2140Noch keine Bewertungen

- Wisdom of Wyckoff2Dokument31 SeitenWisdom of Wyckoff2ngocleasing100% (2)

- MTA Symposium - My Notes (Vipul H. Ramaiya)Dokument12 SeitenMTA Symposium - My Notes (Vipul H. Ramaiya)vipulramaiya100% (2)

- Econ 100.2 Discussion Class 2: 1/25/18 JC PunongbayanDokument30 SeitenEcon 100.2 Discussion Class 2: 1/25/18 JC PunongbayanPauline EviotaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wall Street Revalued: Imperfect Markets and Inept Central BankersVon EverandWall Street Revalued: Imperfect Markets and Inept Central BankersBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- Economics 115: Introductory Microeconomics: Fall 2012Dokument43 SeitenEconomics 115: Introductory Microeconomics: Fall 2012jyp777Noch keine Bewertungen

- SSRN Id3223025Dokument54 SeitenSSRN Id3223025Annisa NurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Princeton University: by Oskar MorgensternDokument10 SeitenPrinceton University: by Oskar MorgensternChevy TeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Challenges To Business EthicsDokument34 SeitenChallenges To Business EthicsAdean RockNoch keine Bewertungen

- RV HET Indicative 2018Dokument8 SeitenRV HET Indicative 2018Paa Kwesi OduroNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Extraordinary Power of Negotiations in Game TheoryVon EverandThe Extraordinary Power of Negotiations in Game TheoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Powell and Zwolinski The Ethical and Economic Case Against Sweatshop LaborDokument24 SeitenPowell and Zwolinski The Ethical and Economic Case Against Sweatshop LaborEngr Gaddafi Kabiru MarafaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review MonopolyDokument8 SeitenLiterature Review Monopolyafduaciuf100% (1)

- International Political Economy NotesDokument52 SeitenInternational Political Economy NotesTal100% (6)

- Film Essay TopicsDokument8 SeitenFilm Essay Topicsafibaubdfmaebo100% (2)

- Class # 2 and 3Dokument51 SeitenClass # 2 and 3William Cordoba CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pasar Dan Etika Dalam IslamDokument11 SeitenPasar Dan Etika Dalam IslamAbid Ar RobbaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economics in 40 CharactersDokument24 SeitenEconomics in 40 CharactersJETRON VELASCONoch keine Bewertungen

- No Bosses: A New Economy for a Better WorldVon EverandNo Bosses: A New Economy for a Better WorldBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (2)

- FDI and Political Risk Mini Case 6jYVszDT1oDokument7 SeitenFDI and Political Risk Mini Case 6jYVszDT1oNikitha NithyanandhamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eco 162Dokument17 SeitenEco 162msukri_81Noch keine Bewertungen

- Market Failure Tyler CowanDokument34 SeitenMarket Failure Tyler CowanalexpetemarxNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Do We Need To FixDokument10 SeitenWhat Do We Need To Fixkoyuri7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Textual Equivalence-CohesionDokument39 SeitenTextual Equivalence-CohesionTaufikNoch keine Bewertungen

- MATHMATICAL Physics Book Career EndaevourDokument293 SeitenMATHMATICAL Physics Book Career EndaevourSwashy Yadav100% (1)

- RSBACDokument166 SeitenRSBACtradersanNoch keine Bewertungen

- AbDokument13 SeitenAbSk.Abdul NaveedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Exemplar On Contextualizing Science Lesson Across The Curriculum in Culture-Based Teaching Lubang Elementary School Science 6Dokument3 SeitenLesson Exemplar On Contextualizing Science Lesson Across The Curriculum in Culture-Based Teaching Lubang Elementary School Science 6Leslie SolayaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SQ3R Is A Reading Strategy Formed From Its LettersDokument9 SeitenSQ3R Is A Reading Strategy Formed From Its Letterschatura1989Noch keine Bewertungen

- SINGLE OPTION CORRECT ACCELERATIONDokument5 SeitenSINGLE OPTION CORRECT ACCELERATIONShiva Ram Prasad PulagamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sony Kdl-42w654a rb1g PDFDokument100 SeitenSony Kdl-42w654a rb1g PDFMihaela CaciumarciucNoch keine Bewertungen

- E F Schumacher - Small Is BeautifulDokument552 SeitenE F Schumacher - Small Is BeautifulUlrichmargaritaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Galletto 1250 User GuideDokument9 SeitenGalletto 1250 User Guidesimcsimc1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Welcome To Word GAN: Write Eloquently, With A Little HelpDokument8 SeitenWelcome To Word GAN: Write Eloquently, With A Little HelpAkbar MaulanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peak Performance Cricket ExtractDokument5 SeitenPeak Performance Cricket ExtractRui CunhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Me-143 BcmeDokument73 SeitenMe-143 BcmekhushbooNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7949 37085 3 PBDokument11 Seiten7949 37085 3 PBAman ChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fractions, Decimals and Percent Conversion GuideDokument84 SeitenFractions, Decimals and Percent Conversion GuideSassie LadyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambridge C1 Advanced Exam Overview PDFDokument1 SeiteCambridge C1 Advanced Exam Overview PDFrita44Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shriya Arora: Educational QualificationsDokument2 SeitenShriya Arora: Educational QualificationsInderpreet singhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eps-07 Eng PDFDokument54 SeitenEps-07 Eng PDFPrashant PatilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing and Validating a Food Chain Lesson PlanDokument11 SeitenDeveloping and Validating a Food Chain Lesson PlanCassandra Nichie AgustinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pineapple Peel Extract vs Calamansi Extract Stain RemoverDokument13 SeitenPineapple Peel Extract vs Calamansi Extract Stain RemoverShebbah MadronaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Fascination TranslatedDokument47 SeitenMental Fascination Translatedabhihemu0% (1)

- The Four Humor Mechanisms 42710Dokument4 SeitenThe Four Humor Mechanisms 42710Viorel100% (1)

- Syllabus in Study and Thinking SkillsDokument5 SeitenSyllabus in Study and Thinking SkillsEnrique Magalay0% (1)

- Forensic psychology: false confessions exposedDokument19 SeitenForensic psychology: false confessions exposedBoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 015-Using Tables in ANSYSDokument4 Seiten015-Using Tables in ANSYSmerlin1112255Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reservoir Characterization 3 LoggingDokument47 SeitenReservoir Characterization 3 LoggingMohamed AbdallahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Controversial Aquatic HarvestingDokument4 SeitenControversial Aquatic HarvestingValentina RuidiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project SELF Work Plan and BudgetDokument3 SeitenProject SELF Work Plan and BudgetCharede BantilanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Practice of TratakaDokument7 SeitenThe Practice of TratakaNRV APPASAMY100% (2)

- I. Introduction To Project Report:: Banking MarketingDokument5 SeitenI. Introduction To Project Report:: Banking MarketingGoutham BindigaNoch keine Bewertungen