Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

U.S. v. Vassiliev Order

Hochgeladen von

Mike KoehlerCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

U.S. v. Vassiliev Order

Hochgeladen von

Mike KoehlerCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page1 of 13

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

10

11

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

12

Plaintiff,

13

14

15

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

ORDER GRANTING MOTIONS TO

DISMISS

v.

YURI SIDORENKO, ALEXANDER

VASSILIEV, and MAURICIO SICILIANO,

Defendants.

16

17

No. 3:14-cr-00341-CRB

In this case, the United States government urges the application of federal criminal

statutes to prosecute foreign defendants for foreign acts involving a foreign governmental

entity. The government has charged Defendants Yuri Sidorenko, Alexander Vassiliev, and

Mauricio Siciliano with five counts: (1) Conspiracy to Commit Honest Services Wire Fraud,

in violation of 18 U.S.C. 1349; (2) Honest Services Wire Fraud, in violation of 18 U.S.C.

2, 1343; (3) Conspiracy to Solicit and to Give Bribes Involving a Federal Program, in

violation of 18 U.S.C. 371; (4) Soliciting Bribes Involving a Federal Program, in violation

of 18 U.S.C. 2, 666(a)(1)(B); and (5) Giving Bribes involving a Federal Program, in

violation of 18 U.S.C. 2, 666(a)(2). Two of the three defendants1 move to dismiss the

Indictment (Ind.), arguing: (1) that the Indictment fails to state an offense because the wire

fraud and bribery charges do not apply extraterritorially; (2) that the charges violate due

28

1

Defendant Yuri Sidorenko has not appeared to date.

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page2 of 13

process because there is an insufficient domestic nexus to prosecute Defendants in the United

States; (3) that the wire fraud and bribery charges are defective as alleged; and (4) that

Defendant Siciliano enjoys immunity from prosecution by virtue of his employment with a

United Nations specialized agency. See generally Motions to Dismiss (MTDs) (dkts.

3233).

The Court hereby GRANTS the Motions to Dismiss based on Defendants first two

6

7

arguments, and does not reach the second two arguments.

I.

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

BACKGROUND2

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) is a United Nations

10

specialized agency headquartered in Montreal, Canada. Ind. 1, 8. One of ICAOs

11

responsibilities is standardizing machine-readable passports. Id. 2. The standards that

12

ICAO established were used to determine which features would be utilized in passports in a

13

variety of countries, including the United States. Id. From 20052010, the United States, a

14

member of ICAO, made annual monetary contributions to ICAO exceeding $10,000 per year.

15

Id. 1, 3. Those contributions constituted 25% of ICAOs annual budget.3 Id.

16

Siciliano was an employee of ICAO and was specifically assigned to work in the

17

Machine Readable Travel Documents Programme. Id. 8. Siciliano worked and resided in

18

Canada, where ICAO is headquartered. Id. He held a Canadian passport but is a Venezuelan

19

national. Id. Sidorenko and Vassiliev4 were chairmen of a Ukranian conglomerate of

20

companies that manufactured and supplied security and identity products, called the EDAPS

21

Consortium (EDAPS). Id. 4, 78.5 Sidorenko is a citizen of Ukraine, Switzerland, and

22

23

24

The facts in this section are taken from the Indictment and accepted as true for purposes of the

Motions to Dismiss. See United States v. Buckley, 689 F.2d 893, 897 (9th Cir. 1982).

3

25

26

The Indictment does not specify how much money the United States contributed annually, but

the Indictment does state that ICAOs annual budget was at least $64,699,000. Id. 3. Thus, the United

States presumably contributed millions of dollars to ICAO each year. See Governments Response to

MTDs (Resp.) at 9, 14.

27

28

Vassiliev is Sidorenkos nephew. Ind. 7.

In the relevant time period, Sidorenko was the Chairman of EDAPSs Advisory Council and

effectively controlled EDAPS, and Vassiliev was EDAPSs Chairman of the Board. Id. 78.

2

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page3 of 13

St. Kitts & Nevis, but he primarily resided in Dubai during the relevant time period. Id. 6.

Vassiliev also resided in Dubai, but he is a citizen of Ukraine and St. Kitts & Nevis. Id. 7.

Sidorenko and Vassiliev provided money and other things of value to Siciliano in

3

4

exchange for Siciliano using his position at ICAO, in Canada, to benefit EDAPS, in Ukraine,

as well as Sidorenko and Vassiliev, in Dubai, personally. Id. 10. Siciliano, working in

Canada, sought to benefit the Ukrainian conglomerate EDAPS by introducing and

publicizing EDAPS to government officials and entities, by arranging for EDAPS to appear

at ICAO conferences, and by endorsing EDAPS to other organizations or business contacts.

Id. 1112.

Siciliano assisted Vassilievs girlfriend in obtaining a visa to travel to Canada in 2007.

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

10

11

Id. 15. Around the same time, Siciliano also considered arranging to obtain a visa for

12

Sidorenko by hiring Sidorenko as a consultant for ICAO. Id. 16. Additionally, the three

13

defendants arranged to have Defendant Sicilianos son sent to Dubai to work for Sidorenko.

14

Id. 20. During this time period, Siciliano, who worked in Canada, wrote an e-mail message

15

to Vassiliev, residing in Dubai, seeking payment of dues via wire transfer to a Swiss bank

16

account. Id. 17.

A few years later, Siciliano, still in Canada, sent an e-mail advising Vassiliev and

17

18

Sidorenko, still in Dubai, that they owed him three months payment. Id. 18. A few weeks

19

after this email, Siciliano sent another email to Vassiliev referencing future projects,

20

receiving the fruits of [their] marketing agreement[,] and inquiring about picking up his

21

dues. Id. 19.

All of this conduct occurred outside of the United States between three defendants

22

23

who are not United States citizens, who never worked in the United States, and whose use of

24

wires did not reach or pass through the United States. See generally id.

25

II.

26

LEGAL STANDARD

On a motion to dismiss pursuant to Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 12(b), the

27

allegations of the indictment must be viewed as a whole and taken as true. See Boyce Motor

28

Lines, Inc. v. United States, 342 U.S. 337, 343 n.16 (1952); Buckley, 689 F.2d at 897. The

3

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page4 of 13

indictment shall be a plain, concise[,] and definite written statement of the essential facts

constituting the offense charged. Fed. R. Crim. P. 7(c). The Ninth Circuit has held that an

indictment setting forth the elements of the offense is generally sufficient. United States v.

Fernandez, 388 F.3d 1199, 1220 (9th Cir. 2004); see also United States v. Woodruff, 50 F.3d

673, 676 (9th Cir. 1995) (In the Ninth Circuit, [t]he use of a bare bones

informationthat is one employing the statutory language aloneis quite common and

entirely permissible so long as the statute sets forth fully, directly[,] and clearly all essential

elements of the crime to be punished.) Additionally, when considering a motion to dismiss

the indictment, the indictment should be read in its entirety, construed according to common

10

sense, and interpreted to include facts which are necessarily implied. United States v.

11

Berger, 473 F.3d 1080, 1103 (9th Cir. 2007) (citing United States v. King, 200 F.3d 1207,

12

1217 (9th Cir. 1999)). Finally, in reviewing a motion to dismiss, the Court is bound by the

13

four corners of the indictment. United States v. Boren, 278 F.3d 911, 914 (9th Cir. 2002).

14

III.

DISCUSSION

15

A. Extraterritorial Application of Criminal Statutes

16

Siciliano and Vassiliev both argue that the Indictment should be dismissed because

17

18

19

the crimes charged do not apply extraterritorially. See generally MTDs. The Court agrees.

1. Morrison

In Morrison v. Natl Australia Bank Ltd., the Court considered the extraterritorial

20

application of Section10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act. 561 U.S. 247, 254 (2010). In

21

reviewing a motion to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), the Court held

22

without dissent that [w]hen a statute gives no clear indication of an extraterritorial

23

application, it has none. Id. at 255 (emphasis added). Although Morrison was a civil case,

24

the Court stated that it applies the presumption [against extraterritorial application] in all

25

cases. Id. at 261. Additionally, the Court held that inferences regarding what Congress

26

might have intended are insufficient; for a court to apply a statute extraterritorially, Congress

27

must give a clear and affirmative indication that the statute applies extraterritorially. Id.

28

at 265; see also Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., 133 S. Ct. 1659, 1665 (2013) (holding

4

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page5 of 13

that the Alien Tort Claims Act does not have extraterritorial effect because nothing in the

text of the statute suggests that Congress intended causes of action recognized under it to

have extraterritorial reach) (emphasis added).

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

After Morrison, lower courts began to reconsider the extraterritorial application of

various federal statues. See, e.g., Loginovskaya v. Batratchenko, 764 F.3d 266, 27172 (2d

Cir. 2014) (holding that the Commodities Exchange Act cannot be applied extraterritorially).

Post-Morrison, the Ninth Circuit held that RICO does not apply extraterritorially in a civil

or criminal context. United States v. Chao Fan Xu, 706 F.3d 965, 974 (9th Cir. 2013). The

Ninth Circuit also recognized that Morrison created a strong presumption that enactments of

10

Congress do not apply extraterritorially. Keller Found./Case Found. v. Tracy, 696 F.3d 835,

11

844 (9th Cir. 2012). However, the Ninth Circuit has yet to decide whether the bribery and

12

wire fraud statues at issue in this case have extraterritorial reach. See United States v.

13

Kazazz, 592 F. Appx 553, 554 (9th Cir. 2014) (holding, as to a defendant charged with

14

numerous counts, one of which was wire fraud, that the court need not reach the issue of

15

extraterritorial application: Because the stipulated facts show a sufficient domestic nexus

16

with the United States for the mail-fraud and wire-fraud counts, we need not address whether

17

these statutes have extraterritorial application.).6

18

Relying on Morrison, Vassiliev and Siciliano argue that because the statutes, as

19

enacted, do not contain a clear indication of an extraterritorial application[,] the Indictment

20

fails to state an offense. See 561 U.S. 247, 254; Vassiliev MTD at 59.

21

22

Two provisions of the bribery statute are charged here. Ind. 3437. The first

bribery provision is violated when a defendant

corruptly solicits or demands for the benefit of any person, or

accepts or agrees to accept, anything of value from any person,

intending to be influenced or rewarded in connection with any

23

24

25

6

26

27

28

The government points to the holding in Kazazz that [t]he Anti-Kickback Act and 18 U.S.C.

371 by their nature implicate the legitimate interests of the United States. See Resp. at 11; 592 Fed.

Appx at 555. That holding was premised on reasoning from a case decided 37 years before Morrison

that specifically stated that because the statute at issue was silent as to its application abroad, the court

was faced with finding the construction that Congress intended. Id.; United States v. Cotten, 471 F.2d

744, 750 (9th Cir. 1973) (emphasis added). This inference into Congresss intent is precisely what

Morrison disallows. See 561 U.S. at 255, 257.

5

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page6 of 13

business, transaction, or series of transactions of such

organization, government, or agency involving any thing of value

of $5,000 or more.

18 U.S.C. 666(a)(1)(B). The second bribery provision is violated when a defendant

corruptly gives, offers, or agrees to give anything of value to any

person, with intent to influence or reward an agent of an

organization or of a State, local or Indian tribal government, or any

agency thereof, in connection with any business, transaction, or

series of transactions of such organization, government, or agency

involving anything of value of $5,000 or more.

4

5

6

7

18 U.S.C. 666(a)(2); see also Ind. 2728. In neither bribery provision is there clear

8

language indicating extraterritorial application.

9

The same is true of the wire fraud statute charged in this case, which provides:

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

10

Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or

artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property by means

of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises,

transmits or causes to be transmitted by means of wire, radio, or

television communication in interstate or foreign commerce, any

writings, signs, signals, pictures, or sounds for the purpose of

executing such scheme or artifice, shall be fined under this title or

imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both. If the violation

occurs in relation to, or involving any benefit authorized,

transported, transmitted, transferred, disbursed, or paid in

connection with, a presidentially declared major disaster or

emergency (as those terms are defined in section 102 of the Robert

T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42

U.S.C. 5122)), or affects a financial institution, such person shall

be fined not more than $1,000,000 or imprisoned not more than 30

years, or both.

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

18 U.S.C. 1343; see also Ind. 2728. Congress did not include in the wire fraud statute

20

any language indicating that it applies extraterritorially.7 The wire fraud statute does mention

21

foreign commerce. 18 U.S.C. 1343. But this mere mention does not overcome the

22

presumption against extraterritoriality. In fact, Morrison addressed statutes that include the

23

phrase foreign commerce and held that even statutes that contain a broad language in their

24

7

25

26

27

28

The government argues that courts may consult context, in addition to the language of the

statute, to determine extraterritorial application, relying on language that Morrison directs at the

concurrence: Assuredly, context can be consulted as well. Resp. at 2024; Morrison, 561 U.S. at 265.

But the government fails to address Morrisons next sentence: But whatever sources of statutory

meaning one consults to give the most faithful reading of the text, [ . . . ], there is no clear indication

of extraterritoriality here. See id. The government also fails to provide any authority that other sources

of statutory meaning, such as legislative history, provide any context demonstrating that the bribery and

wire fraud statutes here apply abroad. Although the government claimed for the first time at the motion

hearing that legislative history supported its position, it failed to specify any.

6

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page7 of 13

definitions of commerce that expressly refer to foreign commerce do not apply abroad.

561 U.S. at 26263 (quoting EEOC v. Arabian Am. Oil Co. (Aramco), 499 U.S. 244, 248

(1991)); see also European Community v. RJR Nabisco, Inc., 764 F.3d 129 (2d Cir. 2014)

(holding after Morrison, that [Section] 1343 cannot be applied extraterritorially).

5

6

text of [either statute] to indicate extraterritorial application. See Tr. (dkt. 47) at 8:4-5.

Under Morrison, without a clear and affirmative indication of Congresss intent to have

the bribery and wire fraud statutes apply extraterritorially, the presumption is that they do

not. See 561 U.S. at 265.

10

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

Indeed, the government agreed at the motion hearing that [t]here is nothing in the

11

2. Bowman

The government argues, however, that a 1922 Supreme Court case allows for the wire

12

fraud and bribery statutes to apply abroad. Resp. at 414. In United States v. Bowman, the

13

Court held that a statute criminalizing conspiracy to defraud a corporation in which the

14

United States was the sole stockholder applied extraterritorially. 260 U.S. 94 (1922). While

15

Bowman may still be good law, the governments reliance on it here is misplaced. Bowman

16

involved United States citizens who were working for a corporation that was wholly owned

17

by the United States. Id. at 9495. Those facts are very different from the facts at hand,

18

which involve foreign citizens working for foreign entities, and whose actions were begun

19

and committed outside of the United States. See, e.g., Ind. 25, 37. Indeed, in Bowman,

20

in addition to the three United States citizen defendants to whom the Courts holdings

21

applied, there was a fourth defendant, a subject of Great Britain, who had not been

22

apprehended. 260 U.S. at 102. As to that defendant, the Bowman court held that it will be

23

time enough to consider what, if any, jurisdiction the District Court below has to punish him

24

when he is brought to trial. Id. at 10203 (emphasis added). This is hardly a ringing

25

endorsement for the application of American criminal laws to foreign actors.

26

27

28

Further, the government acknowledges Bowmans holding that frauds of all kinds

would not have extraterritorial application:

Crimes against private individuals or their property, like assaults,

murder, burglary, larceny, robbery, arson, embezzlement, and

7

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page8 of 13

frauds of all kinds, which affect the peace and good order of the

community must, of course, be committed within the territorial

jurisdiction of the government where it may properly exercise it. If

punishment of them is to be extended to include those committed

out side of the strict territorial jurisdiction, it is natural for

Congress to say so in the statute, and failure to do so will negative

the purpose of Congress in this regard.

1

2

3

4

5

Bowman, 260 U.S. at 98 (emphasis added); Resp. at 6. However, the government points to

subsequent language in Bowman that carves out an exception for a narrow class of criminal

statutes:

8

9

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

10

11

12

13

14

15

But the same rule of interpretation should not be applied to

criminal statutes which are, as a class, not logically dependent on

their locality for the governments jurisdiction, but are enacted

because of the right of the government to defend itself against

obstruction, or fraud wherever perpetrated, especially if committed

by its own citizens, officers, or agents. Some such offenses can

only be committed within the territorial jurisdiction of the

government because of the local acts required to constitute them.

Others are such that to limit their locus to the strictly territorial

jurisdiction would be greatly to curtail the scope and usefulness of

the statute and leave open a large immunity for frauds as easily

committed by citizens on the high seas and in foreign countries as

at home. In such cases, Congress has not thought it necessary to

make specific provision in the law that the locus shall include the

high seas and foreign countries, but allows it to be inferred from

the nature of the offense.

16

Bowman, 260 U.S. at 98 (emphasis added); see also Resp. at 6. The government latches on

17

to the phrase not logically dependent on [its] locality for the governments jurisdiction,

18

ignores the language about the alleged fraud having been committed by [the United

19

Statess] own citizens, officers, or agents, and fails to point the Court to any legislative

20

history supporting the notion that either statute was enacted because of the right of the

21

government to defend itself. See Resp. at 9; Bowman, 260 U.S. at 98 (emphasis added).

22

That a statute might today be a desirable tool for the government to use in defending

23

itself does not mean that it was enacted with todays circumstances in mind. One cannot in

24

good faith argue that the generic wire fraud statute charged here, of which the United States

25

is not the only or inevitable victim, was enacted because of the right of the government to

26

defend itself against foreign frauds. See Bowman, 260 U.S. at 98. The bribery statute

27

charged here at least pertains to bribery concerning programs receiving Federal Funds,

28

which recognizes a federal interest, but its focus on agents of an organization, or of a State,

8

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page9 of 13

local, or Indian tribal government, or any agency thereof suggests that Congresss concern

was bribes paid to domestic government organizations. See 18 U.S.C. 666(a). The Court

therefore distinguishes the opinion of the district court in United States v. Campbell, 798 F.

Supp. 2d 293, 303 (D.D.C. 2011), which found that Section 666 applied extraterritorially.8

The court in Campbell held that Section 666s design was generally to protect the integrity

of the vast sums of money distributed through Federal programs from theft, fraud, and undue

influence by bribery. Id. at 304. Given that purpose, and a defendant who accepted bribes

while working as a contractor for a United States agency abroad, and would receive those

American funds, id., it is no surprise that the court found that Section 666 allowed the

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

10

11

government to reach a non-citizen.

The governments theory here is that because the United States funds a portion of

12

ICAO, Bowman allows it to prosecute an offense committed against ICAO using the bribery

13

and wire fraud statutes. See Resp. at 9. The cases the government cites in support of this

14

theory, including Campbell, involve United States citizens, events that occurred in or passed

15

through the United States, and/or events that directly affect the territory or agencies of the

16

United States. See, e.g., Cotten, 471 F.2d 744 (finding, where two United States citizens

17

committed crime, that it was inconceivable that Congress, in enacting Section 641 [theft of

18

government property], would proscribe only the theft of government property located within

19

the territorial boundaries of the nation).9 This case involves wholly foreign conduct and

20

21

22

Campbell was the only case cited by the government at the motion hearing in defense of its

argument on Section 666. See Tr. at 10:1620.

9

23

24

25

26

27

28

See also United States v. Weingarten, 632 F.3d 60, 66 (2d Cir. 2011) (holding Bowman

applicable, where the defendant was a United States citizen); United States v. Leija-Sanchez, 602 F.3d

797, 798 (7th Cir. 2010) (citing Bowman where some of the criminal acts committed by the defendant

occurred in the United States); United States v. Lawrence, 727 F.3d 386, 394 (5th Cir. 2013) (applying

Bowman where some defendants were United States citizens and were traveling from the United States

to another country); United States v. Siddiqui, 699 F.3d 690, 70001 (2d Cir. 2012) (applying statutes

extraterritorially where United States-educated defendant was convicted of attempted murder of United

States nationals, attempted murder of United States officers and employees, armed assault of United

States officers and employees, and assault of United States officers and employees); United States v.

Belfast, 611 F.3d 783, 81314 (11th Cir. 2010) (applying statutes extraterritorially where the defendant

was a United States citizen and committed torture and other atrocities abroad); United States v.

McVicker, 979 F. Supp 2d 1154, 1171 (D. Or. 2013) (applying Bowman where defendant was a United

States citizen and was indicted for producing and transporting child pornography while living abroad);

9

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page10 of 13

wholly foreign actors. In addition, unlike in Campbell, there are no allegations here actually

implicating the governments interest in protect[ing] the integrity of the vast sums of money

distributed through Federal programs. See id. at 304. There is no allegation that even one

dollar of the millions of dollars the United States presumably sent to ICAO was squandered.

Congress could not, in enacting Section 666, have envisioned that it could be applied

extraterritorially to prosecute foreign crime in which the United Statess investment was not

harmed.

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

3. Conclusion as to Extraterritoriality

At the motion hearing, the Court asked government counsel to imagine a hypothetical

10

in which (1) the United States sent money to Mexico for programs involving security at the

11

border, and (2) an official in Mexico running one aspect the security program took a bribe

12

from his brother-in-law in exchange for getting his brother-in-laws child a job. Tr. at

13

9:1723. The Court asked the government whether the government could prosecute that

14

Mexican official, and the government responded that such a prosecution would be

15

appropriate under Section 666 (and under Section 1343 if it involved a wire). Tr. at

16

9:2410:5. That assertion illustrates the governments overreach here. Of course, the United

17

States has some interest in eradicating bribery, mismanagement, and petty thuggery the world

18

over. But under the governments theory, there is no limit to the United Statess ability to

19

police foreign individuals, in foreign governments or in foreign organizations, on matters

20

completely unrelated to the United Statess investment, so long as the foreign governments or

21

organizations receive at least $10,000 of federal funding. This is not sound foreign policy, it

22

is not a wise use of scarce federal resources, and it is not, in the Courts view, the law.

23

Because there is no clear indication of extraterritorial intent in either statute as

24

required by Morrison, nor does either statute fall into the narrow class of cases enacted

25

because of the right of the government to defend itself against . . . fraud wherever

26

27

28

Campbell, 798 F. Supp. 2d at 303 (defendant who worked for a United States agency accepted bribes

while working as a contractor for the agency abroad).

10

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page11 of 13

perpetrated, especially if committed by its own citizens, officers, or agents, identified in

Bowman, the Court finds that neither statute applies extraterritorially.10

B. Due Process

Vassiliev and Siciliano also argue that the Indictment must be dismissed because the

Due Process Clause requires a sufficient domestic nexus, and the Indictment fails to allege

this. See, e.g., Vassiliev MTD at 911. Again, the Court agrees.

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

In the Ninth Circuit, in order to apply extraterritorially a federal criminal statute to a

defendant consistent with due process, there must be a sufficient nexus between the

defendant and the United States so that such an application of a domestic statute to the

10

alleged conduct would not be arbitrary or fundamentally unfair. United States v. Davis, 905

11

F.2d 245, 24849 (9th Cir. 1990) (internal citation omitted). This requirement ensures that

12

a United States court will assert jurisdiction only over a defendant who should reasonably

13

anticipate being haled into court in this country. United States v. Klimavicius-Viloria, 144

14

F.3d 1249, 1257 (9th Cir. 1998) (quoting World-Wide Volkwagen Corp. v. Woodson, 444

15

U.S. 286, 297 (1980)).

16

Vassiliev and Siciliano argue that the only nexus between them and the United States

17

is that the United States partially funds ICAO, the United Nations agency for which Siciliano

18

(but neither Vassiliev nor Sidorenko) worked. See Vassiliev MTD at 10. Both defendants

19

characterize this link as tenuous. See Vassiliev MTD at 10. The government makes two

20

notable counterarguments. See Resp. at 1415.11

21

22

23

10

24

25

The substantive bribery and wire fraud charges only account for three of the five counts

charged in the Indictment; however, the other two counts are conspiracy to commit these crimes. Thus,

it follows that conspiracy to commit these same crimes cannot apply extraterritorially either.

11

26

27

28

A third is so weak as to defy understanding. The government cites Davis, 905 F.2d at 24849,

in which, according to the government, the Ninth Circuit concluded that prosecuting the defendant for

violating the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act based on his extraterritorial conduct did not violate

due process because his conductattempting to smuggle contraband into United States

territorywould have caused criminal acts within the United States. Resp. at 14. Of course, here,

none of the criminal acts touched the United States, or would have logically caused criminal acts within

the United States. There is no nexus as there was in Davis.

11

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page12 of 13

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

First, the government contends that it does not violate due process in instances in

which charged conduct involve[s] non-U.S. citizens and occurred entirely abroad[,] because

a jurisdictional nexus exists when the aim of that activity is to cause harm inside the United

States. Resp. at 14 (citing United States v. Mostafa, 965 F. Supp.2d 451, 458 (S.D.N.Y.

2013)). The government subsequently cites various cases from other circuits upholding

jurisdiction where defendants had the intent to cause harm inside the United States. Id. at

1415 (citing, e.g., United States v. Al Kassar, 660 F.3d 108 (2d Cir. 2011); United States v.

Brehm, 691 F.3d 547, 55253 (4th Cir. 2012)). Even accepting this argument, no aim to

harm the United States is alleged anywhere in this Indictment. There is nothing in the

10

Indictment to support the proposition that any of the Defendants knew that the conduct

11

alleged even involved the United States. This case is therefore fundamentally different from

12

one involving the prosecution of terrorists who plotted outside of the United States to bomb

13

American airplanes in Asia, see United States v. Yousef, 327 F.3d 56, 112 (2d Cir. 2003),

14

and the governments belief that the cases are analogous, see Resp. at 15, is troubling.

15

Second, the government contends that the domestic nexus is satisfied by the United

16

Statess financial interest, because it pays millions of dollars annually to ICAO, and by the

17

United Statess security interest, because ICAOs work involves travel and identity

18

documents. See id. at 14. The government cites to literally zero authority in support of this

19

contention. Moreover, as with the governments position about the extraterritorial reach of

20

the relevant statutes, its argument that any financial or security interest supports a domestic

21

nexus proves too much. If everything that had an impact on national security gave the

22

United States the right to drag foreign individuals into court in this country, the minimum

23

contacts requirement would be meaningless. Our financial contributions to a foreign

24

organization which does work involving travel and identity documents, and which employs

25

(or employed) someone who illicitly arranged to have his son sent to Dubai, do not present[]

26

the sort of threat to our nations ability to function that merits application of the protective

27

principle of jurisdiction. See United States v. Peterson, 812 F.2d 486, 494 (9th Cir. 1987).

28

Moreover, the money that the United States sent to ICAO probably increases the contacts

12

United States District Court

For the Northern District of California

Case3:14-cr-00341-CRB Document54 Filed04/21/15 Page13 of 13

that the United States has with ICAO, but it is difficult to see how it results in adequate

contacts with Siciliano, who neither lived in, worked in, nor directed any of his alleged

conduct at the United States, let alone Sidorenko or Vassiliev, who did not even work for

ICAO. The government also nowhere explains how much money the United States must

send to a foreign employer (or the foreign employer of an individual one is bribing) to satisfy

the minimum contacts requirement as to a foreign employee (or the individuals bribing him).

In the hypothetical the Court gave the government at the motion hearing, the United States

certainly has a financial interest in the money it sends to Mexico, and a security interest in

the border. But it would be both arbitrary and fundamentally unfair to assert jurisdiction

10

over the corrupt Mexican official or his brother-in-law, who would never reasonably

11

anticipate being haled into court in this country. See Klimavicius-Viloria, 144 F.3d at

12

1257.

13

Because there is an insufficient domestic nexus between the Defendants and the

14

United States, the relevant statutes cannot be applied consistent with due process.

15

IV.

CONCLUSION

16

For the foregoing reasons, the Indictment is DISMISSED.

17

IT IS SO ORDERED.

18

19

CHARLES R. BREYER

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

Dated: April 21, 2015

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

G:\CRBALL\2014\341\order granting MTDs.wpd

13

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Consular convention Between the People's Republic of China and The United States of AmericaVon EverandConsular convention Between the People's Republic of China and The United States of AmericaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIA Conspiracy: San Pasqual Complaint Part OneDokument49 SeitenBIA Conspiracy: San Pasqual Complaint Part OneOriginal PechangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 718 F.2d 1210 (1983)Von EverandU.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 718 F.2d 1210 (1983)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mouli Cohen - Government's Response For Bail Pending SentencingDokument20 SeitenMouli Cohen - Government's Response For Bail Pending SentencingBrian WillinghamNoch keine Bewertungen

- 05-25-2016 ECF 458 USA V PETER SANTILLI - USA Response To Santilli Motion Bill of ParticularsDokument9 Seiten05-25-2016 ECF 458 USA V PETER SANTILLI - USA Response To Santilli Motion Bill of ParticularsJack RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asset Forfeiture Attorney Brief Re Forfeiture of TrademarkDokument13 SeitenAsset Forfeiture Attorney Brief Re Forfeiture of TrademarkDaniel BallardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Memo in Support, Shawn RiceDokument30 SeitenMemo in Support, Shawn Riceajeocci100% (1)

- United States v. McConville, 10th Cir. (2006)Dokument7 SeitenUnited States v. McConville, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- USA v. Samuel Mouli Cohen - October 13, 2010 Filing Opposing BailDokument17 SeitenUSA v. Samuel Mouli Cohen - October 13, 2010 Filing Opposing BailBrian WillinghamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marshals Defense ArgumentDokument301 SeitenMarshals Defense ArgumentCasieNoch keine Bewertungen

- OOO Brunswick v. Sultanov (Ex Parte Seizure Order - DTSA)Dokument8 SeitenOOO Brunswick v. Sultanov (Ex Parte Seizure Order - DTSA)Ken VankoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Order Granting Motion For Preliminary InjunctionDokument13 SeitenOrder Granting Motion For Preliminary InjunctionSon Burnyoaz100% (1)

- Xbox Live Order DismissedDokument11 SeitenXbox Live Order DismissedSiouxsie LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- R. Kelly Motion To DismissDokument11 SeitenR. Kelly Motion To DismissTodd FeurerNoch keine Bewertungen

- SecuritystudiesamicusDokument11 SeitenSecuritystudiesamicuslegalmattersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To Amend ComplaintDokument8 SeitenMotion To Amend ComplaintRoy Warden100% (1)

- Oklahoma National Guard RulingDokument29 SeitenOklahoma National Guard RulingKFOR0% (1)

- Fouts V Becerra (Baton Second Amendment) ComplaintDokument14 SeitenFouts V Becerra (Baton Second Amendment) Complaintwolf woodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case 2:10-cv-01429-GEB-CMK Document 82 Filed 03/11/11 Page 1 of 10Dokument10 SeitenCase 2:10-cv-01429-GEB-CMK Document 82 Filed 03/11/11 Page 1 of 10mnapaul1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Opposition To Motion To Dismiss - FILEDDokument18 SeitenOpposition To Motion To Dismiss - FILEDVince4azNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zima Digital Assets - U.S. Response To Motion 4/6/20Dokument15 SeitenZima Digital Assets - U.S. Response To Motion 4/6/20Michael HaleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- J Int Criminal Justice 2003 Akande 618 50Dokument0 SeitenJ Int Criminal Justice 2003 Akande 618 50haseeb_javed_9Noch keine Bewertungen

- ASSIGNMENT DID NOT MAKE IT INTO THE TRUST BY CUTOFF DATE - Naranjo V SBMC Mortg, S.D.cal. - 3-11-Cv-02229 - 20 (July 24, 2012)Dokument16 SeitenASSIGNMENT DID NOT MAKE IT INTO THE TRUST BY CUTOFF DATE - Naranjo V SBMC Mortg, S.D.cal. - 3-11-Cv-02229 - 20 (July 24, 2012)83jjmack100% (1)

- (42a) OBJECTION DEFENDANT IS CONTESTING PERSONAL JURISDICTION AND MUST DISCHARGE MATTERDokument10 Seiten(42a) OBJECTION DEFENDANT IS CONTESTING PERSONAL JURISDICTION AND MUST DISCHARGE MATTERDavid Dienamik0% (1)

- McCrory Motion To Withdraw Guilty PleaDokument19 SeitenMcCrory Motion To Withdraw Guilty Pleathe kingfish100% (2)

- 36 Order Dismissing CaseDokument7 Seiten36 Order Dismissing CaseStr8UpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Danielle Dyer v. Dirty World, LLC - Order Granting Defendant's Motion For Summary JudgmentDokument9 SeitenDanielle Dyer v. Dirty World, LLC - Order Granting Defendant's Motion For Summary JudgmentDavid S. GingrasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rubin v. Cubic DefenseDokument42 SeitenRubin v. Cubic DefenseShurat HaDin - Israel Law CenterNoch keine Bewertungen

- L.A. Triumph v. Madonna (C.D. Cal. 2011) (Order Granting Motion To Dismiss Madonna From Case)Dokument11 SeitenL.A. Triumph v. Madonna (C.D. Cal. 2011) (Order Granting Motion To Dismiss Madonna From Case)Charles E. ColmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- William B. Richardson v. United States of America, 465 F.2d 844, 3rd Cir. (1972)Dokument43 SeitenWilliam B. Richardson v. United States of America, 465 F.2d 844, 3rd Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Middleton V United Church of ChristDokument23 SeitenMiddleton V United Church of ChristHoward FriedmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sierra Club v. BNSF Railway, 13-cv-00967 (W.D. Wash.)Dokument16 SeitenSierra Club v. BNSF Railway, 13-cv-00967 (W.D. Wash.)Justin A. SavageNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crypto Capital Detention MemorandumDokument7 SeitenCrypto Capital Detention MemorandumAnonymous aISWG6QrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bruce SiddleDokument70 SeitenBruce Siddleneutech11Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 04 04 Order Staying in Part Judgment Pending AppealDokument6 Seiten2019 04 04 Order Staying in Part Judgment Pending AppealBeth BaumannNoch keine Bewertungen

- USA V Stanton Doc 18 Filed 12 Oct 12Dokument7 SeitenUSA V Stanton Doc 18 Filed 12 Oct 12scion.scionNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. v. Siriwan (DOJ Brief)Dokument16 SeitenU.S. v. Siriwan (DOJ Brief)Mike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judicial Watch v. Secret Service (09-2312)Dokument19 SeitenJudicial Watch v. Secret Service (09-2312)FedSmith Inc.Noch keine Bewertungen

- In Re: Elke Magdalena Lesso, 9th Cir. BAP (2013)Dokument12 SeitenIn Re: Elke Magdalena Lesso, 9th Cir. BAP (2013)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 36 US Opp To MTDsDokument9 Seiten36 US Opp To MTDsKolby Kicking WomanNoch keine Bewertungen

- PT United Can Company Ltd. v. Crown Cork & Seal Company, Inc., F/k/a Continental Can Company Richard Krzyzanowski John W. Conway, 138 F.3d 65, 2d Cir. (1998)Dokument14 SeitenPT United Can Company Ltd. v. Crown Cork & Seal Company, Inc., F/k/a Continental Can Company Richard Krzyzanowski John W. Conway, 138 F.3d 65, 2d Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Harry Davidoff, Salvatore Santoro, Frank Manzo, Henry Bono, Jr., Frank Calise, John Russo, Heino Benthin, Pasquale Raucci, Leone Manzo, and William Barone, 845 F.2d 1151, 2d Cir. (1988)Dokument8 SeitenUnited States v. Harry Davidoff, Salvatore Santoro, Frank Manzo, Henry Bono, Jr., Frank Calise, John Russo, Heino Benthin, Pasquale Raucci, Leone Manzo, and William Barone, 845 F.2d 1151, 2d Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Et Al.,: Memorandum Opinion & OrderDokument16 SeitenEt Al.,: Memorandum Opinion & OrderJordan MickleNoch keine Bewertungen

- E. Steven Dutton v. Wolpoff and Abramson, 5 F.3d 649, 3rd Cir. (1993)Dokument13 SeitenE. Steven Dutton v. Wolpoff and Abramson, 5 F.3d 649, 3rd Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Always Smiling Productions v. ChubbDokument11 SeitenAlways Smiling Productions v. ChubbTHROnlineNoch keine Bewertungen

- 50Dokument38 Seiten50Spencer SheehanNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: Docket No. 05-4770-crDokument10 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: Docket No. 05-4770-crScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Election Worker Lawsuit DismissalDokument12 SeitenElection Worker Lawsuit DismissalJessica HillNoch keine Bewertungen

- A E: S T: Anchez Lamas V RegonDokument20 SeitenA E: S T: Anchez Lamas V RegonjohndavidgrangerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neilsen SentencingDokument9 SeitenNeilsen SentencingYTOLeaderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filed: Patrick FisherDokument20 SeitenFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- EXHIBIT 012 B - NOTICE of Libel of Review in AdmiraltyDokument6 SeitenEXHIBIT 012 B - NOTICE of Libel of Review in AdmiraltyJesse Garcia100% (1)

- Saffon FeesDokument16 SeitenSaffon FeesfleckaleckaNoch keine Bewertungen

- USA v. Vallmoe Shqaire - Government's Sentencing PositionDokument75 SeitenUSA v. Vallmoe Shqaire - Government's Sentencing PositionLegal InsurrectionNoch keine Bewertungen

- DOJ Response To Motion To Colorado City Motion To Dismiss 091312Dokument21 SeitenDOJ Response To Motion To Colorado City Motion To Dismiss 091312Lindsay WhitehurstNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metalclad v. Mexico - AwardDokument35 SeitenMetalclad v. Mexico - Awardodin_siegreicherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petroleum Co., 569 U.S. - (2013) (Slip Opinion Attached As Exhibit A) - Adopting Essentially TheDokument38 SeitenPetroleum Co., 569 U.S. - (2013) (Slip Opinion Attached As Exhibit A) - Adopting Essentially TheEquality Case FilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attorneys For Plaintiffs (Additional Counsel Listed On Following Page)Dokument10 SeitenAttorneys For Plaintiffs (Additional Counsel Listed On Following Page)Gus BovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- USA V Michael J Miske JR - Motion To Declare Case ComplexDokument15 SeitenUSA V Michael J Miske JR - Motion To Declare Case ComplexIan LindNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Reader's Digest Association, Inc., 662 F.2d 955, 3rd Cir. (1981)Dokument23 SeitenUnited States v. Reader's Digest Association, Inc., 662 F.2d 955, 3rd Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. v. Enrique Pere YcazaDokument18 SeitenU.S. v. Enrique Pere YcazaMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- NG Jury InstructionsDokument72 SeitenNG Jury InstructionsMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. v. Antonio Pere YcazaDokument21 SeitenU.S. v. Antonio Pere YcazaMike Koehler100% (1)

- Teva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Dokument38 SeitenTeva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Mike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

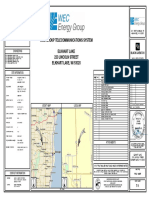

- Wec Group Telecommunications System Elkhart Lake 220 Lincoln Street Elkhart Lake, Wi 53020Dokument18 SeitenWec Group Telecommunications System Elkhart Lake 220 Lincoln Street Elkhart Lake, Wi 53020Mike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teva Whistleblower Writ of MandamusDokument47 SeitenTeva Whistleblower Writ of MandamusMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposed FCPA AmendmentsDokument13 SeitenProposed FCPA AmendmentsMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. v. Bahn (Sentencing)Dokument28 SeitenU.S. v. Bahn (Sentencing)Mike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lyons Bribery ChargesDokument13 SeitenLyons Bribery ChargesHNN100% (10)

- SEC v. CoburnDokument17 SeitenSEC v. CoburnMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Swedish Court Decision Re Telia ExecsDokument99 SeitenSwedish Court Decision Re Telia ExecsMike Koehler100% (2)

- Chatburn IndictmentDokument15 SeitenChatburn IndictmentMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- SEC v. Chiquita Brands (FCPA)Dokument6 SeitenSEC v. Chiquita Brands (FCPA)Mike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lambert IndictmentDokument24 SeitenLambert IndictmentJacciNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. v. Transport Logistics Int'l (Order)Dokument3 SeitenU.S. v. Transport Logistics Int'l (Order)Mike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. v. Ho (DOJ Response Brief)Dokument31 SeitenU.S. v. Ho (DOJ Response Brief)Mike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. V Ho Motion To DismissDokument27 SeitenU.S. V Ho Motion To DismissMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Africo Resources Ltd. LetterDokument26 SeitenAfrico Resources Ltd. LetterMike Koehler100% (1)

- SEC Opposition Brief To Cohen - Baros Motion To DismissDokument110 SeitenSEC Opposition Brief To Cohen - Baros Motion To DismissMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canada Should Say No To DPAsDokument19 SeitenCanada Should Say No To DPAsMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sandra Moser RemarksDokument6 SeitenSandra Moser RemarksMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davis Polk Bio-Rad ReportDokument20 SeitenDavis Polk Bio-Rad ReportMike KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ghana Copyright - Us GovDokument13 SeitenGhana Copyright - Us GovkamradiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Covert Surveillance & InvestigationDokument3 SeitenProfessional Covert Surveillance & Investigation360 International LimitedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Missing Murdered Indigenous WomenDokument10 SeitenMissing Murdered Indigenous Womenapi-533839695Noch keine Bewertungen

- Club Love and Lust: SLA Letter Motion Seeking Reconsideration and ReinstatementDokument172 SeitenClub Love and Lust: SLA Letter Motion Seeking Reconsideration and ReinstatementEric SandersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Computer Forensics and InvestigationsDokument103 SeitenComputer Forensics and InvestigationsMarco AlmeidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Punjab Destitute and Neglected Children Act 2004Dokument14 SeitenPunjab Destitute and Neglected Children Act 2004averos12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fair Trial Due ProcessDokument19 SeitenFair Trial Due ProcessZeesahn100% (1)

- Tragedy of The Plains IndiansDokument23 SeitenTragedy of The Plains Indiansprofstafford100% (1)

- 41 - Park Hotel Vs Soriano (2012) - Tan, RDokument3 Seiten41 - Park Hotel Vs Soriano (2012) - Tan, RNeil BorjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Past Year) ELC501 TEST PAPER (NOV 17)Dokument11 Seiten(Past Year) ELC501 TEST PAPER (NOV 17)umie mustafaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A2010 Torts DigestsDokument134 SeitenA2010 Torts DigestsLibay Villamor IsmaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Panel 3 PPT - Preparing For The GDPRDokument21 SeitenPanel 3 PPT - Preparing For The GDPRgschandel3356Noch keine Bewertungen

- Endpoint SecurityDokument6 SeitenEndpoint SecurityRobby MaulanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise 1 LogicDokument3 SeitenExercise 1 LogicBrenda Fernandes33% (3)

- Jennifer Agostini CaseDokument2 SeitenJennifer Agostini CaseErin LaviolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Twelve Angry Men Study Guide Act One QuestionsDokument3 SeitenTwelve Angry Men Study Guide Act One QuestionsailynNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADL Report "Attacking" Press TVDokument20 SeitenADL Report "Attacking" Press TVGordon DuffNoch keine Bewertungen

- PP Vs Salazar - PP OrillosaDokument73 SeitenPP Vs Salazar - PP OrillosaEleasar Banasen PidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frm23fla Firearms Licence Application FormDokument35 SeitenFrm23fla Firearms Licence Application FormMariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 05/06/15Dokument4 SeitenPeoria County Booking Sheet 05/06/15Journal Star police documents100% (1)

- Final Special Crime Investigation With Legal Medicine ReviewDokument203 SeitenFinal Special Crime Investigation With Legal Medicine ReviewRaquel IgnacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Credit Secrets Mini-Book, From The Makers of The Official Credit Secrets BibleDokument11 SeitenThe Credit Secrets Mini-Book, From The Makers of The Official Credit Secrets BibleTedNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Anderson, 4th Cir. (2002)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Anderson, 4th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Issues and Problems in Public Fiscal AdministrationDokument2 SeitenIssues and Problems in Public Fiscal AdministrationYeah Seen Bato Berua88% (43)

- Basic Hacking Techniques - Free Version PDFDokument369 SeitenBasic Hacking Techniques - Free Version PDFAung AungNoch keine Bewertungen

- A8 People V Dawaton - DigestDokument1 SeiteA8 People V Dawaton - DigestErwin BernardinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terri Grier Transcript 08192016Dokument5 SeitenTerri Grier Transcript 08192016Nathaniel Livingston, Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Decora Blind Systems LTD Equal Opportunities Monitoring FormDokument1 SeiteDecora Blind Systems LTD Equal Opportunities Monitoring FormJames KennyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Causes of Armed Conflict C2Dokument7 SeitenThe Causes of Armed Conflict C2Roxana AlexandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- PSA Celebrity TrackerDokument34 SeitenPSA Celebrity Trackerwonkette666100% (1)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansVon EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (19)

- The Girls Are Gone: The True Story of Two Sisters Who Vanished, the Father Who Kept Searching, and the Adults Who Conspired to Keep the Truth HiddenVon EverandThe Girls Are Gone: The True Story of Two Sisters Who Vanished, the Father Who Kept Searching, and the Adults Who Conspired to Keep the Truth HiddenBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (37)

- Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIVon EverandHearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (20)

- Broken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.Von EverandBroken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (45)

- Witness: For the Prosecution of Scott PetersonVon EverandWitness: For the Prosecution of Scott PetersonBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (44)

- A Special Place In Hell: The World's Most Depraved Serial KillersVon EverandA Special Place In Hell: The World's Most Depraved Serial KillersBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (55)

- Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of HollywoodVon EverandTinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of HollywoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gardner Heist: The True Story of the World's Largest Unsolved Art TheftVon EverandThe Gardner Heist: The True Story of the World's Largest Unsolved Art TheftNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our Little Secret: The True Story of a Teenage Killer and the Silence of a Small New England TownVon EverandOur Little Secret: The True Story of a Teenage Killer and the Silence of a Small New England TownBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (86)

- Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorVon EverandBind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (77)

- If You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodVon EverandIf You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (1804)

- Blood Brother: 33 Reasons My Brother Scott Peterson Is GuiltyVon EverandBlood Brother: 33 Reasons My Brother Scott Peterson Is GuiltyBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (57)

- The Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalVon EverandThe Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (104)

- Restless Souls: The Sharon Tate Family's Account of Stardom, the Manson Murders, and a Crusade for JusticeVon EverandRestless Souls: The Sharon Tate Family's Account of Stardom, the Manson Murders, and a Crusade for JusticeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perfect Murder, Perfect Town: The Uncensored Story of the JonBenet Murder and the Grand Jury's Search for the TruthVon EverandPerfect Murder, Perfect Town: The Uncensored Story of the JonBenet Murder and the Grand Jury's Search for the TruthBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (68)

- The Franklin Scandal: A Story of Powerbrokers, Child Abuse & BetrayalVon EverandThe Franklin Scandal: A Story of Powerbrokers, Child Abuse & BetrayalBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (45)

- In My DNA: My Career Investigating Your Worst NightmaresVon EverandIn My DNA: My Career Investigating Your Worst NightmaresBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- Relentless Pursuit: A True Story of Family, Murder, and the Prosecutor Who Wouldn't QuitVon EverandRelentless Pursuit: A True Story of Family, Murder, and the Prosecutor Who Wouldn't QuitBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (7)

- In the Name of the Children: An FBI Agent's Relentless Pursuit of the Nation's Worst PredatorsVon EverandIn the Name of the Children: An FBI Agent's Relentless Pursuit of the Nation's Worst PredatorsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (241)

- Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock's Darkest DayVon EverandAltamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock's Darkest DayBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (25)

- R.A.W. Hitman: The Real Story of Agent LimaVon EverandR.A.W. Hitman: The Real Story of Agent LimaBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Diamond Doris: The True Story of the World's Most Notorious Jewel ThiefVon EverandDiamond Doris: The True Story of the World's Most Notorious Jewel ThiefBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (18)

- Nicole Brown Simpson: The Private Diary of a Life InterruptedVon EverandNicole Brown Simpson: The Private Diary of a Life InterruptedBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (16)

- True Crime Case Histories - (Volumes 4, 5, & 6): 36 Disturbing True Crime Stories (3 Book True Crime Collection)Von EverandTrue Crime Case Histories - (Volumes 4, 5, & 6): 36 Disturbing True Crime Stories (3 Book True Crime Collection)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Hell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryVon EverandHell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryBewertung: 2.5 von 5 Sternen2.5/5 (3)