Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Wendy Chill

Hochgeladen von

Aarti JCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Wendy Chill

Hochgeladen von

Aarti JCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

UVA-C-2206

Rev. Feb. 18, 2014

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

WENDYS CHILI: A COSTING CONUNDRUM

What happens to a successful company when it loses its founder, senior chairman,

advertising icon, and beloved leader? That was the question being asked about Wendys

International, Inc., in January 2002 after Dave Thomas, 69, passed away from cancer. In the

words of Jack Schuessler, the companys chairman and CEO, Dave was our patriarch. He was

the heart and soul of our company. Without him, the company would never be the same. But

Dave Thomas left behind a legacy about values, ethics, product quality, customer satisfaction,

employee satisfaction, community service, and shareholder value that provided a solid

foundation on which to continue the success the company had experienced for more than 30

years. Still, the patriarch was gone, and the future was uncertain.

How It Began

Wendys International, Inc., was founded by R. David Thomas in Columbus, Ohio, in

November 1969. Prior to that time, Thomas had purchased an unprofitable Kentucky Fried

Chicken franchise in the Columbus area, turned it around, and subsequently sold it back to

Kentucky Fried Chicken at a substantial profit. He then became a cofounder of Arthur Treachers

Fish & Chips. So, at the time he founded Wendys, Thomas was no stranger to the quick-service

restaurant industry.

Although he had been involved with businesses specializing in chicken and fish,

Thomass favorite food was hamburgers, and he frequently complained that there was no place

in Columbus to get a really good hamburger without waiting 30 minutes or more. Someone

finally suggested (whether in earnest or in jest was debatable) that he get into the hamburger

business and do it his way. After thinking it over, thats just what he did, and he named his new

company after his eight-year-old daughter, Wendy. His goal was to provide consumers with

bigger and better hamburgers that were cooked to order, served quickly, and reasonably priced.

By offering what he believed was a different product, Wendys went after a different segment of

the hamburger marketyoung adults and adults. In so doing, Thomas did not view his company

as just another hamburger chain.

This case was prepared by Professor E. Richard Brownlee II. It was written as a basis for class discussion rather than

to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright 2005 by the University of

Virginia Darden School Foundation, Charlottesville, VA. All rights reserved. To order copies, send an e-mail to

sales@dardenbusinesspublishing.com. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or otherwisewithout the permission of the Darden School Foundation.

Page 1 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

-2-

UVA-C-2206

Wendys International, Inc., chose as its trademark what the company called the oldfashioned hamburger. This was a hamburger made from fresh beef that was cooked to order and

served directly from the grill to the customer. So that customers could see what they were eating,

old-fashioned hamburgers were square in shape so as to extend beyond the round buns on

which they were served. The unique shape also differentiated a Wendys hamburger from those

of other restaurants. Thomas felt that one way for Wendys to remain price competitive and still

serve a better-quality product was to limit the number of menu items. Thus, he decided on four

main products: hamburgers, chili, French fries, and Wendys Frosty Dairy Dessert. The standard

soft drinks and other beverages were also included.

Wendys old-fashioned hamburgers were pattied fresh daily from 100% pure domestic

beef and served hot n juicy in accordance with individual customer orders. Customers could

choose either a single (one quarter-pound patty), a double (two quarter-pound patties), or a triple

(three quarter-pound patties). With the many condiments available, Wendys was able to offer

variety (256 possible hamburger combinations) even though its menu was limited to four basic

items. Wendys chili was prepared daily using an original recipe. It was slow-simmered from

four to six hours and served the following day. Each eight-ounce serving contained about a

quarter-pound of ground beef. The same beef patties were used in making chili as were served as

hamburgers. Although it was sometimes necessary to cook beef patties solely for use in making

chili, most of the meat for Wendys chili came from well-done beef patties that could not be

served as hot n juicy old-fashioned hamburgers. These well-done hamburgers were

refrigerated and used in making chili the following day.

Wendys French fries were prepared from high-quality potatoes and were cut slightly

longer and thicker than those served by most other quick-service hamburger chains. The

company used specialized fryers designed to cook the inside of these bigger potatoes without

burning the outside. Wendys Frosty Dairy Dessert was a blend of vanilla and chocolate flavors

and was too thick to drink through a straw. It was served with a spoon to be eaten as a dessert,

but some customers ordered a Frosty in place of a soft drink. Whether served as a dessert or as a

dairy drink, the Frosty was a distinctive and popular menu item.

Initial Growth

The first Wendys restaurant opened in Columbus, Ohio, in November 1969. The second

Wendys opened in 1970, restaurants three and four opened in 1971, and restaurants five, six,

and seven opened in 1972. In addition to these seven company-operated stores, two franchised

restaurants were opened in 1972. As shown in Table 1, a substantial increase occurred in the

number of Wendys restaurants opened between 1973 and 1978, the majority of which were

franchised units.

Page 2 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

-3-

UVA-C-2206

Table 1. Number of Wendys restaurants in operation, 197378.

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

1973

Company restaurants

17

Franchised restaurants

15

Total restaurants

32

Data sources: Wendys annual reports, 197378.

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

46

47

93

93

159

252

174

346

520

231

674

905

288

1,119

1,407

Both company and franchised restaurants were built to company specifications as to

exterior style and interior decor. Most were freestanding, one-story brick buildings, substantially

uniform in design and appearance, and constructed on approximately 35,000-square-foot sites

with parking for 35 to 40 cars. Freestanding restaurants contained about 2,400 square feet and

included a cooking and food preparation area, a dining room designed to seat 92 customers, and

a pick-up window to serve drive-thru customers. Wendys restaurants were usually located in

urban or densely populated suburban areas, and their success depended upon serving a large

volume of customers. As of December 31, 1978, the 288 company restaurants were located in 18

multi-county areas in and around the cities listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Company restaurants, December 31, 1978.

Columbus, OH

Cincinnati, OH

Dayton, OH

Toledo, OH

Atlanta, GA

Indianapolis, IN

Fort Worth, TX

32

19

24

10

28

12

9

Detroit, MI

11

Oklahoma City, OK

10

Tulsa, OK

10

Memphis, TN

11

Louisville, KY

12

Syracuse, NY

8

West Virginia

32

Tampa, Sarasota, St. Petersburg, and

Houston, TX

18

20

Clearwater, FL

Dallas, TX

11

Jacksonville, FL

11

Note: At this time, there were no franchised restaurants located in any of the market areas served by

company restaurants.

Data source: Wendys annual report, 1978.

Company Revenues

Wendys initial revenues came from four principal sources. As shown in Table 3, these

were sales made by company restaurants, royalties paid by franchise owners (franchisees),

technical assistance fees paid by franchise owners, and interest earned on investments. The

increase in the percentage of total revenues that resulted from royalties during the five-year

period covered by Table 3 was primarily caused by the substantial increase that occurred in the

number of franchised restaurants relative to the number of company restaurants.

Page 3 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

-4-

UVA-C-2206

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

Table 3. Percentage revenue composition, 1974-78.

1974

Year Ended December 31

1975

1976

1977

1978

94.21%

3.33

1.53

0.93

93.37%

4.26

1.70

0.67

90.16%

6.40

2.16

1.28

87.10%

9.50

2.04

1.36

84.13%

12.65

1.87

1.35

100.00%

Data sources: Wendys annual reports, 197479.

100.00%

100.00%

100.00%

100.00%

Revenues:

Company restaurants

Royalties

Technical assistance fees

Interest, other income

Revenue from sales made by company restaurants was recognized as soon after the sales

occurred as was practicable. Because the amount of each company restaurants daily net sales

was to be reported to corporate headquarters in Dublin, Ohio, by 8:00 a.m. the next day, they

were generally recorded by the corporate accounting staff the day after the sales were made.

Wendys franchise agreements stipulated that every franchisee had to pay to Wendys

International, Inc., a technical assistance fee for each restaurant the franchisee agreed to build

within the franchised area.1 The due date for payment of the technical assistance fee (sometimes

referred to as a franchise fee) was negotiated with each franchisee. The earliest due date was at

the time the franchise agreement was signed; the latest was 30 days prior to the opening of each

restaurant.

According to Wendys management, the technical assistance fees did not contribute

substantially to company profits inasmuch as they were generally fully expended on providing a

variety of services to franchise owners prior to the opening of each restaurant. These services

included site selection assistance, standard construction plans and specifications, initial training

for franchise owners and restaurant managers, advertising materials and assistance, national

purchasing agreements, and operations manuals. Technical assistance fees received any time

prior to the opening of the related franchised restaurants were recorded by the company as

deferred technical assistance fees. Technical assistance fees were recognized as revenue at the

time the franchised restaurants commenced operations.

Once a franchised restaurant was opened, franchise owners had to pay Wendys

International, Inc., a royalty of 4% of gross sales. In connection therewith, franchisees were

required to submit to the company weekly sales reports (due the following Monday) for each

restaurant. Payment of the royalty was made on a monthly basis and was due, along with a

monthly sales report, by the 15th of the following month. Royalties were recognized on an

accrual basis at the end of each month based on the weekly sales reported by franchisees. If

necessary, these monthly accruals were adjusted at the time the royalty payments were received

from franchisees.

Unlike most other quick-service restaurant chains, Wendys originally granted franchises for geographic areas

(i.e., one or more counties) rather than for individual restaurants.

Page 4 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

-5-

UVA-C-2206

Wendys did not select or employ any personnel for franchisees, nor did the company sell

fixtures, food, or supplies of any kind to franchisees. Also, unlike many other restaurant chains,

Wendys did not derive revenue from owning the franchised units and leasing them to

franchisees. All Wendys franchise owners either owned their franchised restaurants or leased

them from independent third parties. Interest and other income represented the amounts earned

on investments, principally certificates of deposit, bankers acceptances, and commercial paper.

These amounts were recognized by the company on an accrual basis as earned.

Chili and the Wendys Way

Wendys was founded on the belief that the combination of product differentiation,

market segmentation, quality food, quick service, and reasonable prices would produce a

successful company. This combination was often referred to by Dave Thomas as the Wendys

Way. The decision to include chili as one of the original menu items was made after careful

consideration of the most desirable product mix in keeping with the Wendys Way.

The first and most important of Wendys products was, of course, the old-fashioned

hamburger. French fries were the second item included on the menu, primarily because so many

customers ate French fries with their hamburgers. It was at this point that a product decision

needed to be made that would enhance the successful implementation of the Wendys Way.

Wendys management knew that the only way the restaurants could serve old-fashioned

hamburgers directly from the grill in accordance with individual customer orders, and still be

able to serve them quickly, was for the cooks to anticipate customer demand and have a

sufficient supply of hamburgers already cooking when the customers arrived at the restaurants.

The problem with such an approach, however, was what to do with the hamburgers that became

too well done whenever the cooks overestimated customer demand and cooked too many

hamburgers. Throwing them away would be too costly, but serving them as hot n juicy oldfashioned hamburgers would result in considerable customer dissatisfaction. The solution to this

dilemma was in finding a product that was unique to the restaurant industry and that required

ground beef as one of the major ingredients. Thus, Wendys rich and meaty chili became one

of the four original menu items.

Difficulties in the 1980s

Wendys continued its growth in total number of restaurants, revenues, and income

throughout the first half of the 1980s. Responding to competitive pressures and changing

customer demands, Wendys added chicken to its menu through the acquisition of Sisters

International, Inc. The company also expanded and improved its Garden Spot salad bar, added

stuffed baked potatoes to the menu, and changed its restaurant decor to reflect a more upscale

environment. As a means of providing more flexibility in dealing with franchisees and of

facilitating expansion, Wendys began the use of the single-unit franchise method whereby

franchise rights were granted on a restaurant-by-restaurant basis rather than on an area basis as

Page 5 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

-6-

UVA-C-2206

had been the companys previous practice. In 1985, revenues exceeded $1 billion for the first

time, and income set a new record at $76.2 million. Notwithstanding this impressive

performance, management faced some formidable challenges. The U.S. economy was softening,

and lower discretionary consumer spending served to increase competitive pressures in the

quick-service restaurant industry. The companys major competitors had substantially improved

the quality of their products, service, and facilities, and they had been aggressively introducing

new menu items.

The year 1986 turned out to be the worst in the companys history. Total revenues

increased less than 2% over the previous year, and the company recorded a $75 million charge

for business realignment expense. Consequently, Wendys reported a loss for the year of

approximately $5 million, its first loss ever. As an example of the competitive nature of the

industry, Wendys made a strategic decision to serve breakfast on a system-wide basis in June

1985. Shortly thereafter, the economy worsened, and Wendys major competitors introduced

new products targeted specifically at Wendys customers. This created an environment where it

was difficult to justify the investment necessary to accomplish a system-wide breakfast offering.

Therefore, in March 1986, breakfast became an optional menu item for both company and

franchised restaurants.

In 1987, Wendys sold Sisters International, Inc., and began a systematic reduction in the

number of company restaurants both inside and outside the United States. The company also

continued to expand the availability of its new three-section Super Salad Bar, and by year-end, it

was installed at more than 90% of company restaurants and approximately 40% of franchised

restaurants. Due to a $15 million income tax benefit and a $1 million extraordinary gain on early

extinguishment of debt, Wendys reported income of $4.5 million in 1987.

Optimism in the 1990s

As Wendys entered the 1990s, there were indications that the company was about to

regain the momentum it had lost during the latter part of the previous decade. Company

restaurant operating profit margins, return on average assets, and return on average equity had all

begun to improve, and most of the unprofitable company restaurants had been closed. Wendys

was ready to begin a program of prudent, aggressive growth both domestically and

internationally.

One of the interesting debates that occurred from time to time during the realignment

period of the late 1980s and early 1990s had to do with the role of the companys original menu

items in light of the introduction of what became known as Wendys balanced product and

marketing approach. This approach had been introduced to enable the company to respond in a

timely manner to ever-changing customer trends with respect to menu composition and pricing.

Although Wendys had abandoned its original limited menu concept during the late 1970s, the

four original menu items continued to be sold as part of a group of product offerings that

management referred to as the core menu.

Page 6 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

-7-

UVA-C-2206

As a guide for the 1990s, management identified six specific operating objectives, which

then became known as the keys to success. Key #1 was to grow the total number of Wendys

restaurants, with a goal of 5,000 by 1995. Key #2 was to generate consistent real sales growth

(e.g., without price increases) from quarter to quarter. Key #3 was to continue to improve

restaurant operating margins. Key #4 was to manage corporate overhead expenses prudently.

Key #5 was to enhance return on assets. And Key #6 was to continue to strengthen the entire

restaurant system through the selective sale of company units to strong existing or new

franchisees, while acquiring units in need of attention from existing franchisees.

In addition to Wendys new operating objectives, the company continued to experiment

with new menu items throughout the 1990s. In March 1992, the company began offering five

fresh salads to go. In addition, the company introduced a spicy chicken sandwich, and it then

added a five-piece chicken nugget item to its 99-cent Super Value menu. Managements hard

work paid off, and the company added almost 2,000 restaurants during the decade.

A significant event occurred for the company in December 1995, when the company

merged with Tim Horton, a coffee and baked goods company headquartered in Canada. This

merger enabled both companies to expand their own operations across the United StatesCanada

border and provided a strong foundation for further expansion of Wendys and Tim Hortons

franchise operations.

The Challenges of the New Millennium

The new millennium brought many changes to Wendys. John Jack T. Schuessler was

named CEO and chairman of the board in March 2000, and the company opened its 6,000th

restaurant in October 2001. But these milestones were overshadowed by the death of Dave

Thomas in January 2002. Maintaining the momentum of the past decade was going to depend on

Wendys ability to establish itself as the franchisor of choice for franchisees, the employer of

choice for employees, and the restaurant of choice for customers. Thus, one of the most critical

aspects of customer satisfaction had to do with the quality, price, and variety of the products

sold. Menu decisions would likely become increasingly important as Wendys continued to

implement its portfolio approach of Super Value menu items, specialty menu items, and core

menu items.

As the company began its post-Dave Thomas era, management thought that perhaps the

time had come to give serious consideration to eliminating at least one of the original menu

items. Of these, chili seemed to be the most likely candidate. In addition to being the menu

maverick, chili represented a relatively small percentage of total restaurant sales, and there was

considerable controversy over its true profit margin. The issue, it seemed, had to do with

determining the actual cost of a bowl of chili. This same issue had, in fact, been debated but

never resolved back in 1979 when Wendys salad bar was introduced. Thus, regardless of the

ultimate menu decision, management was determined to figure out once and for all what a bowl

of chili really cost.

Page 7 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

-8-

UVA-C-2206

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

Costing the Chili

Wendys chili was prepared daily by the assistant manager, in accordance with Wendys

secret recipe. It was slow-simmered in a double boiler on a separate range top for a period of

four to six hours. While cooking, the chili had to be stirred at least once each hour, and at the end

of the day it was refrigerated for sale the following day.

Normally, it took between 10 and 15 minutes to prepare a pot (referred to at Wendys as a

batch) of chili. First, the 48 quarter-pound cooked ground beef patties needed for a batch were

obtained, if available, from the walk-in cooler. This took about one minute. These patties had

been well-done sometime during the previous three days. Most of the time, it was not

necessary to cook meat specifically for use in making chili, although the need to do so was more

likely to occur during the months of October through March when approximately 60% of total

annual chili sales occurred. If, as only happened approximately 10% of the time, it became

necessary to cook meat specifically for use in making chili, the number of beef patties needed

were taken from the trays of uncooked hamburgers that had been prepared using a special patty

machine, at the rate of 120 patties every five minutes, earlier that morning. On average, it took

10 minutes to cook 48 hamburger patties.

Before it was placed in the chili pot, the meat had to be chopped into small pieces. This

generally took about five minutes to do. The remaining ingredients then had to be obtained from

the shelves and mixed with the meat. This process also took about five minutes to complete, after

which the chili was ready to be cooked. The quantities and costs of the ingredients needed to

make a batch of chili and the labor costs associated with the different classifications of restaurant

personnel are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Other direct costs associated with the chili included

serving bowls, $0.035 each; lids for chili served at the carry-out window, $0.025 each; and

spoons, $0.01 each.

Table 4. Chili ingredients and costs.

Quantity

Description

Cost

No. 10 can of crushed tomatoes

$2.75/can

46-oz. cans of tomato juice

$1.25/can

Wendys seasoning packet

$1.00/packet

No. 10 cans of red beans

$2.25/can

Cooked quarter-pound ground beef patties

(12 lb. of ground beef)

$3.50/lb.

Note: The batch of chili described above yielded approximately 57 8-ounce servings.

1

5

1

2

48

Table 5. Restaurant labor costs.

Description

Cost

Store Manager

$800.00/week (salary)

Co-Manager

$12.50/hour

Assistant Manager

$10.50/hour

Management Trainee

$7.00/hour

Crew

$5.75/hour

Note: Payroll taxes and other employee-related costs averaged about 10% of the above amounts.

Page 8 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

-9-

UVA-C-2206

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

Chili Sales

The selling prices for all Wendys products sold by company restaurants were set at

corporate headquarters. Although some price differences existed among restaurants in different

locations, representative prices for 2001 were $0.99 for an 8-ounce serving of chili, $1.59 for a

12-ounce serving of chili, and $1.89 for a single hamburger. Chili sales were seasonal, and

comprised about 5% of total Wendys store sales compared with about 55% for hamburgers. As

shown in Exhibit l, Wendys consolidated cost of sales, as a percentage of retail revenues,

increased to 63.8% in 2001 from 63.1% in 2000. Food costs in 2001 reflected a 13.4% increase

in beef costs, which was partially offset by a 1.6% selling price increase. Retail sales increased

by 6.5%, and net income increased by about 14% during 2001.

Required

1. How was Wendys able to achieve its initial success and to grow so rapidly at a time

when the quick-service hamburger business appeared to be saturated?

2. What benefits might have resulted from Wendys limited menu concept? What were

the disadvantages of such a concept? Why was the concept eventually discontinued?

3. Why was Wendys drive-through window successful when other quick-service restaurant

chains had been unsuccessful at implementing the same concept?

4. How much does a bowl of chili cost on a full-cost basis? An out-of-pocket basis?

5. For determining the true profitability of chili, how much does a bowl of chili really cost?

6. Would you recommend dropping chili from the menu? Why or why not?

Page 9 of 10

DardenBusinessPublishing:215916

-10-

UVA-C-2206

Exhibit 1

WENDYS CHILI: A COSTING CONUNDRUM

This document is authorized for use only by Irish Anderson at University of Arkansas - Little Rock.

Please do not copy or redistribute. Contact permissions@dardenbusinesspublishing.com for questions or additional permissions.

Statement of Income for the Years Ended December 31, 2001, and 2000

(in thousands, except per-share data)

2001

Revenue:

Retail operations

Other, principally interest

2000

$1,925,319

465,878

$2,391,197

$1,807,841

429,105

$2,236,946

Costs and expenses:

Cost of sales

1,229,277

Company restaurant operating costs

406,185

Operating costs

91,701

General and administrative expenses

216,124

Depreciation and amortization of property and equipment 118,280

International charges

Other expense

1,722

Interest, net

20,528

$2,083,817

1,140,840

382,963

86,272

208,173

108,297

18,370

5,514

15,080

$1,965,509

Income before income taxes

Income taxes

307,380

113,731

271,437

101,789

$ 193,649

$ 169,648

Net income per common and common equivalent share

$1.65

$1.44

Dividends per common share

$0.24

$0.24

Net income

Data sources: Wendys annual reports, 20002001.

Page 10 of 10

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- American Finance Association, Wiley The Journal of FinanceDokument8 SeitenAmerican Finance Association, Wiley The Journal of FinanceAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting Homework Help IliskimeDokument1 SeiteAccounting Homework Help IliskimeAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- CostingDokument3 SeitenCostingAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deegan Chapter 10Dokument18 SeitenDeegan Chapter 10Aarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Capital Market Intermediaries and Their RegulationDokument8 Seiten6 Capital Market Intermediaries and Their RegulationTushar PatilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hi5019 Individual Assignment t1 2019 Qyuykqw5Dokument5 SeitenHi5019 Individual Assignment t1 2019 Qyuykqw5Aarti J50% (2)

- NCK - Annual Report 2017 PDFDokument56 SeitenNCK - Annual Report 2017 PDFAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- CR 1845Dokument90 SeitenCR 1845Aarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saudi Vision2030Dokument85 SeitenSaudi Vision2030ryx11Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - Sis40215 CPT Case Studies 3Dokument61 Seiten1 - Sis40215 CPT Case Studies 3Aarti J0% (2)

- Caltex Australia CTX 2017 Annual ReportDokument127 SeitenCaltex Australia CTX 2017 Annual ReportAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mgt201 Solved Subjective Questions Vuzs TeamDokument12 SeitenMgt201 Solved Subjective Questions Vuzs TeamAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Investment Decision MethodDokument44 SeitenInvestment Decision MethodashwathNoch keine Bewertungen

- TFTH C 636639530213947535 31700 2Dokument55 SeitenTFTH C 636639530213947535 31700 2Aarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH 07 SMDokument11 SeitenCH 07 SMAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

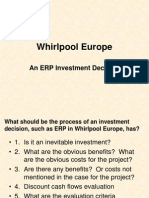

- The Whirlpool Europe Case: Investment On ERPDokument8 SeitenThe Whirlpool Europe Case: Investment On ERPAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 7 Inventory Problem Solutions Assessing Your Recall 7.1Dokument32 SeitenChapter 7 Inventory Problem Solutions Assessing Your Recall 7.1Judith DelRosario De RoxasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ch03 Prob3-6ADokument9 SeitenCh03 Prob3-6AAarti J100% (1)

- Coles Year in Review 2017Dokument28 SeitenColes Year in Review 2017Aarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mergers Don't Always Lead To Culture Clashes.Dokument3 SeitenMergers Don't Always Lead To Culture Clashes.Lahiyru100% (3)

- Organizational CultureDokument21 SeitenOrganizational CultureAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Case - 2Dokument10 Seiten2 Case - 2Aarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study Ch03Dokument3 SeitenCase Study Ch03Munya Chawana0% (1)

- Relevant Cost Examples EMBA-garrison Ch.13Dokument13 SeitenRelevant Cost Examples EMBA-garrison Ch.13Aarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philanthropy Hub Opens To Advisers Australian Share Valuations Overstretched'Dokument2 SeitenPhilanthropy Hub Opens To Advisers Australian Share Valuations Overstretched'Aarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2010 06 13 - 091545 - Case13 30Dokument6 Seiten2010 06 13 - 091545 - Case13 30Sheila Mae Llamada Saycon IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting Changes and Errors: HapterDokument46 SeitenAccounting Changes and Errors: HapterAarti JNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACCG315Dokument4 SeitenACCG315Joannah Blue0% (1)

- Whirlpool EuropeDokument19 SeitenWhirlpool Europejoelgzm0% (1)

- MCK (McKesson Corporation) Annual Report With A Comprehensive Overview of The Company (10-K) 2013-05-07Dokument139 SeitenMCK (McKesson Corporation) Annual Report With A Comprehensive Overview of The Company (10-K) 2013-05-07Aarti J100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Assignment 2: Case Study PHAM KHANH HA - S3877365 Course: - Introduction To Management: 1,500Dokument5 SeitenAssignment 2: Case Study PHAM KHANH HA - S3877365 Course: - Introduction To Management: 1,500Hà KhánhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Goodyear's growth strategy dilemmaDokument2 SeitenGoodyear's growth strategy dilemmawariola100% (1)

- SSRN Id92188Dokument41 SeitenSSRN Id92188christieSINoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint Venture AssignmentDokument14 SeitenJoint Venture AssignmentDeo Prakash0% (2)

- Grille & Bar Business PlanDokument14 SeitenGrille & Bar Business PlanLystra Ong92% (38)

- Strategic Franchising (MGMT 931) Syllabus Fall 2013: Course ContentDokument4 SeitenStrategic Franchising (MGMT 931) Syllabus Fall 2013: Course Contentmilrosebatilo2012Noch keine Bewertungen

- Local and Real Property TaxesDokument103 SeitenLocal and Real Property Taxesrbv005Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Went Wrong E-Bay Case StudyDokument2 SeitenWhat Went Wrong E-Bay Case StudyAsif43% (7)

- Decision,+ERC+Case+No +2014-118+RCDokument35 SeitenDecision,+ERC+Case+No +2014-118+RCDyna EnadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quiz On OPTDokument9 SeitenQuiz On OPTJustine Maureen Andal100% (1)

- Franchising Consignment KeyDokument22 SeitenFranchising Consignment KeyMichael Jay SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- EuroKids Franchise BrochureDokument6 SeitenEuroKids Franchise BrochureSunnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roll Singh 2023Dokument10 SeitenRoll Singh 2023Unnat MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Feasibility Study On Subway Franchise at Panglao, BoholDokument33 SeitenA Feasibility Study On Subway Franchise at Panglao, Boholhanah bahnanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internationalization Strategiesfor ServicesDokument9 SeitenInternationalization Strategiesfor ServicesRadinne Fakhri Al WafaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 9 FDI Collaboration Contracts PDFDokument18 SeitenWeek 9 FDI Collaboration Contracts PDFThuraga LikhithNoch keine Bewertungen

- McDonald's Case Analysis Highlights Key Challenges and OpportunitiesDokument24 SeitenMcDonald's Case Analysis Highlights Key Challenges and OpportunitiesNori Jayne Cosa RubisNoch keine Bewertungen

- RETAIL STORES-MIS BY S.MAHESH, GUMMADIDURRU..9248528762, K.l.universityDokument68 SeitenRETAIL STORES-MIS BY S.MAHESH, GUMMADIDURRU..9248528762, K.l.universitychanti9885458148100% (6)

- Small Business Management Study Questions - CH 4 Franchises and BuyoutsDokument18 SeitenSmall Business Management Study Questions - CH 4 Franchises and BuyoutsStacey Strickling NashNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDokument12 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baskin Robbins Franchisee Model-Jun 2015Dokument21 SeitenBaskin Robbins Franchisee Model-Jun 2015sadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imm - Unit 2Dokument39 SeitenImm - Unit 2CHANDAN CHANDUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modes of Entry Into An International BusinessDokument6 SeitenModes of Entry Into An International Businesspriyank1256Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 11 Joan Holtz ADokument3 SeitenLecture 11 Joan Holtz Avineetk_39100% (1)

- Coca-Cola Porter's Five Forces Analysis and Diverse Value-Chain Activities in Different AreasDokument33 SeitenCoca-Cola Porter's Five Forces Analysis and Diverse Value-Chain Activities in Different AreasRoula Jannoun67% (6)

- Employer Job Offer Streams: Employer's Guide: Ontario Immigrant Nominee ProgramDokument29 SeitenEmployer Job Offer Streams: Employer's Guide: Ontario Immigrant Nominee ProgramSandeep SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CEL 1 TOA Answer Key 1Dokument12 SeitenCEL 1 TOA Answer Key 1Joel Matthew MozarNoch keine Bewertungen

- PanaraDokument22 SeitenPanaraPankaj ChamoliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Franchise BrochureDokument20 SeitenFranchise BrochureTHE BESTMASKNoch keine Bewertungen