Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Polcin-SL & Parolees

Hochgeladen von

AdrianaZarateOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Polcin-SL & Parolees

Hochgeladen von

AdrianaZarateCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

1

What about Sober Living Houses for Parolees?

Douglas L. Polcin, Ed.D.

Research Scientist

Alcohol Research Group

2000 Hearst Avenue, Suite 300

Berkeley, CA 94709-2130

Phone (510) 642-5208

Fax (510) 642-7175

E-Mail: dpolcin@arg.org

In Press: A CRITICAL JOURNAL OF CRIME, LAW AND SOCIETY.

Key Words: Sober Living, Sober House, Parole, Criminal Justice, Oxford House

Supported by NIAAA grant R01 AA014030-03

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

2

Abstract

High recidivism rates for parolees might be reduced with the provision of a stable, drug fee

living environment.

This paper suggests that Sober Living Houses (SLHs) have been

overlooked as housing options for alcohol and drug abusing parolees. Some of the strengths of

these programs include: 1) they are financially self-supporting, 2) they mandate abstinence from

substances, 3) they provide social support for recovery, 4) they mandate or strongly encourage

attendance in 12-step mutual help programs, and 5) they have no maximum lengths of stay. A

description of SLHs, their potential roles in criminal justice systems, and preliminary data on

longitudinal outcome are presented. It is suggested that SLHs could provide drug free living

arrangements for parolees and facilitate the receipt of services for other problems as well.

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

3

Few facts in the criminal justice field have been better documented than the problem of

recidivism among parolees. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (2005) reported that a majority,

55%, of state parole discharges in 2002 failed to complete their supervision. Petersilia (2000)

used Bureau of Justice Statistics to point out that two-thirds of all parolees are rearrested within

three years of their release. Part of the reason for these bleak findings may be that parole

officers are overwhelmed with caseloads at time up to 70 offenders. Hence, monitoring

compliance with parole requirements becomes difficult and losing track of parolees is not

uncommon (Petersilia, 2000). For example, in 1999 alone California parole officers lost track of

about one-fifth of their parolees. Housing instability contributes to problems tracking parolees.

In some large cities, such as Los Angeles and San Francisco, 30% to 50% of parolees are

estimated to be homeless (Petersilia, 2000).

Substance use may be both a consequence and a cause of homelessness. Decades of research

have consistently documented large proportions of prison inmates having alcohol or drug

problems (e.g., Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999; Greenfield, 1988, October; Petersilia, 2000).

Studies conducted in the late 1980s by Greenfield (1988, October) found 58% of a California

sample of inmates had lifetime histories of alcohol abuse or dependence and about half had

histories of drug abuse or dependence.

More recently, the Office of National Drug Control

Policy reported that up to 85% of all state prisoners need addiction treatment but only 13%

receive it while incarcerated (Byrne, et al, 1998, August).

The combination of high prevalence rates of substance abuse and limited treatment is

especially concerning given the consistent finding that legally mandated treatment with

offenders is effective (e.g. Farabee, Prendergast & Anglin, 1998; Polcin, 2001a). The Federal

Bureau of Prisons TRIAD report (Pelisser et al, 2000, September) indicated that residential

treatment for incarcerated prisoners with addiction problems resulted in positive effects on

recidivism, drug use, and employment. Numerous studies have documented that the costs of

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

4

substance abuse treatment programs are by far offset by reduced criminal justice costs (Gerstein

et al, 1994, Farabee, et al, 1998; NIDA, 2005). Nevertheless, funds to expand treatment are

often limited and non-treatment, self sustaining alternatives for addressing addiction problems,

such as Sober Living Houses (SLHs), should be explored. Although a full description of SLHs is

provided below, they may briefly be described as alcohol- and drug-free residences for

individuals attempting to establish or maintain sobriety (Polcin, 2001b).

Parolees face a variety of problems in addition to substance abuse, including mental health,

medical, employment, and homelessness. Petersilia (2000) pointed out that nearly one-fifth of

the inmates in US prisons have mental illness. In California, Greenfield (1988, October) found

that 15% of prisoner inmates met criteria for serious mental disorders. Other problems needing

attention among inmates and those who are paroled include illnesses such as hepatitis and HIV

(Petersilia, 2000). Studies have shown that homelessness among parolees released from prison

is high (up to 50% in some urban areas) and up to 60% of parolees are not employed one year

after their release (Petersilia, 2000).

This paper suggests that few of the issues that parolees present can be adequately addressed

without the provision of safe, stable, and drug free living environments. Outside a social context

that supports substance abuse recovery, parolees are at high risk for drug relapse and the variety

of problems frequently related to addiction. Also, parolees without stable housing are unlikely

to have sufficient stability in their lives to attend parole related appointments promptly or

comply with service provider suggestions.

An argument frequently heard in the popular press and even among various professional

groups is that prison inmates and parolees are not motivated to address addiction or other

problems. However, findings from studies by Greenfield (1990, August) suggest that prison

inmates in fact are motivated for treatment of a variety of problems.

For example, 96%

indicated that they would be willing to accept services for alcohol, drug or emotional problems

after their release if they experienced these problems. Parolees may be especially receptive of

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

5

addressing these types of problems when coupled with supportive, drug free living

environments and they may be more likely to follow through with a referral.

The position of this paper is that SLHs offer enormous potential for improving the fate of

many parolees in multiple problem areas: criminal justice recidivism, homelessness, alcohol

and drug addiction, employment, and mental health. The paper begins with a description of

SLHs, including basic principles, house operations and historical background.

Then, the

mechanisms by which these housing arrangements can affect receipt of help for other problem

areas are described. In addition to the advantages of SLHs for parolees, potential challenges

and limitations are also noted. Finally, we present preliminary outcome findings on a study of

SLHs which includes a comparison of findings for criminal justice referred residents versus

others.

What are Sober Living Houses?

SLHs are alcohol- and drug-free residence for individuals attempting to establish or

maintain sobriety (Polcin, 2001b; Kaskutas, 1999; Wright, 1990). Kaskutas (1999) noted that

SLHs vary a great deal in terms of physical characteristics. Some are small two or three

bedroom houses and others are large, encompassing entire apartment complexes, SRO (single

room occupancy) hotels, or multiple smaller houses. Unlike treatment programs, SLHs do not

provide group counseling, case management, treatment planning or a structure of daily

activities. However, residents are either encouraged or required to attend 12-step meetings such

as Alcoholics Anonymous. A social model of recovery is usually promoted that emphasizes

shared leadership on a rotating residents council, peer support for recovery, financial selfsufficiency, and resident responsibility for maintaining the facility.

Governance and

management by the residents council is especially important because it facilitates responsibility,

communication, and shared commitment. Without one, programs become manager driven

and dependent on the leadership style of the house manager.

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

6

Because SLHs are not licensed or required to report their existence to any agency or local

government, it is difficult to ascertain their exact numbers. However, in California, Sober Living

Housing Associations (SLHAs) such as the Sober Living Network (SLN) and California

Association for Addiction and Recovery Resources (CAARR) report increasing membership of

SLHs. SLHAs provide support, training, advocacy, referrals and health and safety standards to

SLHs that are members. They also promote a social model view of recovery that they believe

facilitates the recovery process. The SLN reports that they have over 250 member houses in

their organization. CAARR has 64 member programs throughout the state that offer sober

living services as an adjunct or alternative to treatment. The director of SLN, Ken Schonlau,

estimates that SLHs exist in a majority of other states in all part of the country (personal

communication, August 15, 2005). Websites that advertise SLH such as www.soberrecovery.com

and www.sober.com list programs in all part of the country.

Recent NIH funded studies on SLHs in California (Polcin et al, 2005, June) and Oxford

Houses (one specific type of sober living residence) in 7 different states (Jason et al., 2005,

August) have shown promising longitudinal outcomes. These studies are long overdue because

sober living and Oxford Houses have enjoyed increasing popularity and growth within the

recovering community since the 1970s (Jason et. al, 2005, August; Polcin, 2001b; Wittman,

Bidderman and Hughes, 1993).

SLHs can be designed as for profit or non-profit organizations. One of the criticisms of some

for-profit houses is that they can be designed and operated more with an eye toward maximizing

the owners financial return rather than fidelity to the principles of social model recovery. These

types of SLHs tend to have a manager driven style of running the house, where the owner

decide the rules and determines who gets admitted. Schonlau (2004, April) differentiates SLHs

that are supervised homes from those that are democratic homes; the former being more

manager driven and the latter more consistent with the principles of social model recovery.

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

7

While most houses advocate for a democratic or social model approach, a sizeable minority are

manager driven.

Oxford Houses

A good example of the democratic model of running SLHs is the Oxford House model.

Oxford Houses are rare in California but common in the other parts of the country. The Oxford

Foundation is a large international organization with over 1,000 houses located throughout the

United States. Oxford houses can be conceived as one specific type of SLH. The Oxford

Foundation has mandatory requirements for houses to use a democratic organizational

structure, share and rotate leadership within the houses, rely on peer support for recovery, and

finance housing costs using resident funds.

In addition, member houses receive training

workshops on how to facilitate a sense of community, mobilize commitment to the house,

manage daily operations, and practice recovery skills from peers.

The Oxford model reflects principles that are central components to the social model

philosophy of recovery as described by Borkman, et al, (1998), Kaskutas (1999), and Polcin

(2001b). They also reflect principles that are promoted by SLHAs such as the SLN and CAAR.

However, historically SLHs not affiliated with SLHAs have not been regulated by any standards

and have had enormous leeway in terms of how houses are managed. For example, some have

lacked an empowered residents council and instead have been lead by a powerful house

manager. Frequently, these types of SLHs are owned by the house manager or the house

manger is the signer for the rental lease and therefore has leverage to make decisions about

house rules and operations unilaterally. Most of these types of SLHs have been for profit

organizations.

History of Sober Living Houses

Much of the information on the history of SLHs reviewed here is taken from Polcin (2001b).

Please see this publication for a more complete description of SLHs and their history.

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

8

Wittman, Biderman, and Hughes (1993) reviewed the history of sober living houses and

pointed out that Temperance Movement advocates in the 1830s influenced the development of

several different types of sober lodging residence: rooming houses, single room occupancy

hotels, religious missions, and service organizations such as the Salvation Army. Many sober

residences in the nineteenth century were run privately by landlords with personal convictions

supporting sobriety. Unlike many contemporary SLHs, they did not practice democratic

participation, shared leadership, or most other principles of Social model Recovery.

The city of Los Angeles has been a major center for SLHs (Whitman, Biderman, and Hughes,

1993).

After World War II the population of Los Angeles expanded considerably and the

proliferation of alcohol problems resulted in the opening of twelfth step houses. These were

clean and sober residences managed by recovering Alcoholics Anonymous members. By the

1960s Los Angeles had several dozen twelfth step houses. SLHs became increasingly popular

in the 1970s when affordable housing began to disappear in Los Angeles and other metropolitan

areas and homelessness increased (Whitman, Biderman, and Hughes, 1993).

A major development in the history of SLHs on the East Coast was the formation of Oxford

House in 1975 in Montgomery County, Maryland (ONeill, 1990). After a county-funded halfway

recovery house was closed because of funding problems, the program participants decided to

continue residing in the house by paying for rent and utilities themselves. They eliminated the

recovery house rules, such as mandatory attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings,

curfews, and a six-month maximum length of stay. The only rules were that residents maintain

sobriety and pay rent and utilities on time. However, most house members attended Alcoholics

Anonymous meetings and others were encouraged to attend. A resident council was formed to

attend to the business needs of the house and membership on the council was rotated to ensure

a democratic decision making process. There was no time limit on residency and individuals

could stay as long as they liked. Anecdotal reports indicated that residents experienced an

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

9

increased sense of independence and pride (ONeill, 1990) and recent NIH outcome studies have

confirmed these reports (Jason et al, 2005, August).

The demand for additional houses increased and other houses were formed. In 1988 the

United States Congress passed Public Law 100-690, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which provided

the states money to loan to individuals wishing to develop sober living residences. Whitman,

Biderman and Hughes (1993) and more recently Whitman et al (1993; 2001) pointed out that

service planners are increasingly interested in integrating tenancy in SLHs with participation in

outpatient treatment programs. It is hoped that this approach can decrease the need for more

expensive hospital inpatient or residential treatment.

SLHs for criminal justice offenders

remains largely untapped.

Advantages and Limitations of Sober Living Residence during Parole

One of the main advantages of using SLHs for parolees with a history of alcohol or drug

abuse is the ease of keeping in touch with such individuals. Tracking parolees has been difficult

for several reasons. First, as noted above, some parole officers have caseloads of 70 parolees

(Petersilia, 2000). Second, a majority of parolees do not complete their supervision and large

proportions become homeless. While placement in a long-term residential treatment program

might in many cases be optimal, there typically few openings in such programs and they have

long waiting lists. Additionally, under managed care and other funding regulations, the lengths

of stay in such programs has continued to decrease, which presents the question of Where are

the going to live (Polcin et al, 2004) after they leave treatment. In SLHs they can stay as long

as they wish.

There are a number of additional advantages to using SLHs for parolees. Typically, they

facilitate compliance with the requirements of parole. For example, like the terms of parole for

most parolees who have addiction problems, SLHs mandate complete abstinence from drugs

and alcohol (Polcin, 2001b). They usually have good informal relationships with a variety of

community service providers, and they encourage residents to utilize community resources as

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

10

needed (Kaskutas, 1999). This can facilitate compliance with community services such as drug

treatment, mental health, or vocational training, which may be a mandated part of the parole

contract. Without the provision of a safe and drug-free living environment that supports

recovery, compliance with these mandated services can be difficult. Even if parolees are able to

stay clean and sober in destructive environments, they may not have sufficient structure and

support to keep appointments in community agencies. In addition, without the presentation of

a better alternative to their previous lives, such as that offered by residence in a SLH, parolees

are likely to revert to their previous antisocial lifestyles.

SLHs may also be a good fit for many parolees because most SLHs empower residents to

have input into the management of the house. Residents are challenged then to take

responsibility for the working of their recovery program and fulfilling house expectations. These

types of responsibilities are typically not experienced while incarcerated, yet they are essential to

successful adaptation in the community. Most residents find employment to meet their

financial obligations, not infrequently with help, advice and job leads from other residents.

Those that use other financial resources are usually required to have some type of positive daily

structure in their lives.

Assessing Readiness for Entering Sober Living Houses

Most SLHs require an assessment for entry into the house that is conducted by the house

manager, the residents council, or both. Typically, they want to see that the potential resident

has begun a program of recovery, either through 12-step programs, other mutual help programs,

or treatment. They want to see evidence or at least motivation for ability to meet the financial

obligations. Finally, they want a person who can contribute to the recovery oriented

environment; someone who can support the recovery of others.

The issues addressed in the assessment interview present significant questions and potential

limitations about the viability of SLHs for some parolees:

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

11

1) What if the parolee has limited financial resources, no job, and has not worked in many years?

SLHs have responded to his issues in several different ways. As mentioned above, other

residents are frequently good resources for potential jobs, some of which do not require previous

experience (e.g. manual labor). Hence, some residents entering the house are able to find work

quickly. Here of course, the resident must be highly motivated and willing to work for low

wages. Additionally, some houses are flexible and will either front or loan one months rent for

highly motivated residents or allow a prospective resident to sleep on the couch and use the

common areas until they find work. However, these are temporary arrangements and usually

residents are only given a month or so leeway. Finally, some agencies which fund treatment and

ancillary services will pay for residence in a clean and sober living environment, such as SLHs,

while the individual attends outpatient treatment. Such is the case in Californias Proposition

36 program, which mandates drug treatment rather than incarceration for nonviolent first time

offenders (Wittman, 2001).

2) What if the person is not motivated for recovery or not ready to take on the level of

responsibility necessary to reside in a sober living community?

This person probably requires a more intensive and structured treatment environment. Even

if they are not motivated, they may nonetheless succeed in criminal justice mandated treatment.

Numerous studies have found that criminal justice mandated clients do as well and in some

cases better than voluntary clients (Farabee, Prendergast & Anglin, 1998; Polcin, 2001a). A

critical gap in the recovery treatment systems, however, is where do clients go after they have

completed the residential treatment program? In addition, where do they live when they are

involved in outpatient treatment? While some treatment programs have transitional or step

down houses that are a structured part of aftercare treatment, beds are usually limited and few

of the clients who need them get them (Polcin, 2001b). Thus, SLHs are an untapped resource

for addressing the important question of where clients are going to live after completing

residential treatment or while they engage in outpatient treatment.

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

12

3) What if the parolee has severe mental health issues that preclude the level of autonomy

required in SLHs?

Many SLHs are able to accommodate people with significant mental health problems,

particularly when symptoms are well controlled with medications and other treatments. Most

houses will allow residents to use Social Security Disability or General Assistance to pay rent

and fees, as long as the amounts are sufficien to cover resident costst. Some individuals may

need more intensively monitored supported housing programs (Rog, 2004). These are houses

in the community usually occupied by individuals with serious mental illness, many of whom

also have problems with alcohol or drugs. They are affiliated with mental health programs and

partially funded by the mental health treatment systems. Residents may occasionally work, but

most are likely to be involved in outpatient day treatment or other types of structured activities.

The supported housing program within a mental health treatment system is often a good

alternative for individuals too disabled to succeed in a typical sober living home.

Preliminary Offender Outcomes in Sober Living Houses

An Evaluation of Sober Living Houses is a 5-year study funded by the National Institute on

Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Polcin, Galloway, Taylor & Benowitz-Fredercks, 2004). It aims

to track 300 individuals living in 19 different SLHs administered by 2 different agencies: Clean

and Sober Transitional Living (CSTL) in Sacramento, California and the Options program in

Berkeley, California. Interviews are conducted at baseline and 6, 12, and 18 month follow-up.

Planned comparisons include an examination of resident outcomes relative to outcomes in a

nearby social model treatment program.

Other comparisons will examine outcomes for

subgroups of residents within the houses, such as criminal justice referrals.

Preliminary data on 73 residents (20% female, 33% non-white) revealed that approximately

45% were still residing in SLHs 6 months post baseline. Participants interviewed at 6 month

follow up indicated that over half (51%) had been completely abstinent from drugs and alcohol

over the past 6 months. Among those who had relapsed, Wilcoxen Signed Rank tests showed

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

13

significant reductions for 6-month measures of alcohol (p<.001) and drug (p<.0001) use when

compared to the 6 months prior to baseline interviews. Baseline and 6 month comparisons on

the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) revealed improvement on employment (p<.01), legal (p<.05)

and family/social (p<.1) severity. Residents entered SLHs with relatively low ASI alcohol (M =

0.15, SD = 0.28) and drug scores (M = 0.07, SD = 0.10) and improvements at 6 months were not

significant. In addition, ASI medical severity did not differ between the two time points, nor did

psychiatric problems as measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory.

Interestingly, few differences were found when we compared those who were in jail or prison

during the 30 days prior to entering the house (n=20) with those who were not (n=53). MannWhitney tests for independent samples found no significant differences between those in jail

versus not in jail at baseline or 6-month follow up. When we examined the amount of change

from baseline to 6-month follow up, again we found no difference between those who had been

in jail or prison versus those who had not. It should be noted that multiple areas of functioning

were assessed, including 6 areas on the Addiction Severity Index (alcohol, drug, medical, legal,

family/social, and vocational ( McLellan, et al, 1992), six month measures of substance use

(Gerstein et al, 1994), social support for sobriety (Zwyak and Longabough, 2002), and

psychiatric functioning (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983).

Conclusion

Parole departments face major challenges trying to keep track of the increasing number of

parolees. A majority of parolees fail to complete their supervision and about two-thirds are

rearrested within three years. The vast majority of offenders have some type of substance abuse

problem and many others present problems with metal health, medical, employment, housing

and medical problems. Perhaps the most important challenge for parole departments is finding

adequate resources to address the multitude of different problems that parolees present. This

paper has argued that addressing the issues for those with addiction problems requires the

provision of a safe, clean and sober living environment. SLHs provide such an environment and

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

14

also support compliance with other types of services that are often mandated by parole (e.g.,

mental health treatment, medical care, vocational training). SLHs may not be an appropriate

choice for parolees who have little desire to stay clean or those who have few financial resources

and are unlikely to succeed in work. However, they appear to be a viable option for many

parolees and some houses have flexibility in terms of how soon payments must be made. In

addition, some treatment funding agencies, such as Californias Proposition 36 program will pay

for some or all of the fees required. Preliminary data assessing SLHs show that residents made

a variety of improvements from baseline to 6-month follow up and that those who were in jail or

prison before entering the SLH improved about as much as those who were not incarcerated.

Future analysis will involve larger numbers of subjects who will be assessed at 12 and 18 months

as well.

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

15

Resources

A variety of organizations are available to individuals and institutions who are interested in

learning more about sober living houses:

1) California Association of Addiction and Recovery Resources (CAARR)

2921 Fulton Avenue, Sacramento, CA 95821-4909

(916) 338-9460

www.CAARR.org

2)Oxford House, Inc.

1010 Wayne Avenue, Suite 400

Silver Spring, MD 20910

(301) 587-2916

www.oxfordhouse.org

3) Sober Living Network

P.O. Box 5235

Santa Monica CA 90409

(301) 396-5270

www.soberhousing.net

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

16

References

Bureau of Justice Statistics (1999). Substance Abuse and treatment, state and federal prisoners,

1997. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Washington, DC: US Department of

Justice.

Bureau of Justice Statistics (2005). Probation and Parole Statistics. Washington DC: US

Department of Justice.

Byrne, C., Faley, J., Flaim, L., Pinol, F., Schmidtlein, J. (1998, August). Drug treatment in the

criminal justice system. Washington DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy.

Derogatis, L.R. & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report.

Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595-605.

Gerstein, D.R., Johnson, R.A., Harwood, H.J., Fountain, D., Sutter, N. & Malloy, K. (1994).

Evaluating recovery services: The California drug and alcohol treatment assessment

(Contract No. 92-001100).

Sacramento: California Department of Alcohol and Drug

Programs.

Greenfield, T. K. (1988, October). A study of major mental disorders in California prisons:

survey methodology

and preliminary estimates. The Annual Meeting of the American

Academy of Psychiatry and Law, San Francisco.

Greenfield, T. K. (1990, August). Voices from the California State prisons: Utilization and

amenability to

treatment during and after incarceration. Annual Meeting of the Society

for the Study of Social Problems, Washington, DC.

Jason, L.A., Ferrari, J.R, Davis, M.I., Olson, B.D., Alvarez, J. & Majer, J. (2005, August). Need

for Community:

The Oxford House Innovation.

Paper presented at the American

Psychological Association Conference in Washington, D.C.;

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

17

Kaskutas, L.A. (1999, April). The Social Model Approach to Substance Abuse Recovery: A

Program of Research and Evaluation.

Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse

Treatment.

McLellan, A.T., Cacciola, J., Kushner, H., Peters, F., Smith, I., Pettinati, H. (1992).

The fifth edition of the addiction Seveity Index: Cautions, additions, and normative data.

Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 9, 199-213.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (1999). Principles of drug addiction treatment (NIH

Publication No. 99-4180). Washington, D.C.: Author.

ONeill, J. (1990). History of Oxford House, Inc. In S. Shaw & T. Borkman (Eds.). Social model

recovery: An environmental approach (pp103-107). Burbank, CA: Bridge Focus Inc.

Pelissierr, B., Rhodes, W., Saylor, W., Gaes, G., Camp, S.D., Vanyur, S.D. & Wallace, S. (2000,

September. TRIAD Drug treatment evaluation project final report of three-year outcomes:

Part 1. Wasnington DC: Federal Bureau of Prisons Office of Research and Evaluation.

Petersilia, J. (2000). When prisoners return to the community: Political, economic, and social

consequence. Sentencing and Corrections, 9, 1-8.

Polcin, D.L. (2001a). Drug and alcohol offenders coerced into treatment: A review of modalities

and suggestions for research on social model programs. Substance Use and Misuse.

36(5), 589-608

Polcin, D.L. (2001b). Sober Living Houses: Potential Roles in Substance Abuse Services and

Suggestions for

Research. Substance Use and Misuse. 36(2), 301-311.

Polcin, D.L. (2004). Bridging Psychosocial Research and Treatment in Community Substance

Abuse Programs. Addiction Research and Theory, 12(3), 275-284.

Polcin, D.L., Galloway, G.P, Taylor, K, Lopez, D. & De Bairracua, I. (2005, June). The ecology of

sober living houses: Adapting to recovery from addiction. Society for Community

Research and Action 10th Biennial Conference. University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Sober Living Houses for

Parolees

18

Rog, D.J. (2004). The evidence on supported housing. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal,

27(4), 334-344.

Schonlau, K. (2004, April). Sober and congregate living: Definitions of two types. Santa Monics,

CA: The Sober Living Network.

Wittman, F.D. (2001).

Prevention, community services and Proposition 36. Journal of

Psychoactive Drugs, 33(4), 343-352.

Witttman, F.D., Biderman, F., & Hughes, L. (Eds.). (1993). Sober living guidebook for alcohol

and drug free housing. (California Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs, ADP 9200248).

Zywiak, W.H. & Longabough (2002). Decomposing the relationships between pretreatment

social characteristics and alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63,

114-121.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research and PracticeVon EverandAddiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research and PracticeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Annotated Bibliography Tomkins 1Dokument9 SeitenRunning Head: Annotated Bibliography Tomkins 1api-303232478Noch keine Bewertungen

- Week 4 - Research Proposal - Diego Reyes - 2016Dokument8 SeitenWeek 4 - Research Proposal - Diego Reyes - 2016api-3426993360% (1)

- 492 Final RecommendationDokument9 Seiten492 Final Recommendationapi-405318047Noch keine Bewertungen

- Why Can't Church Be More Like an AA Meeting?: And Other Questions Christians Ask about RecoveryVon EverandWhy Can't Church Be More Like an AA Meeting?: And Other Questions Christians Ask about RecoveryNoch keine Bewertungen

- HNR 3700 - Community Perceptions of Prison Health Care Final ProposalDokument18 SeitenHNR 3700 - Community Perceptions of Prison Health Care Final Proposalapi-582630906Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research EssayDokument11 SeitenResearch Essayapi-519864021Noch keine Bewertungen

- Report To The New York City Board of CorrectionDokument20 SeitenReport To The New York City Board of CorrectionGotham GazetteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sentencing Project Report 2009Dokument48 SeitenSentencing Project Report 2009Erik LorenzsonnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospice Social Work - Dona J. ReeseDokument26 SeitenHospice Social Work - Dona J. ReeseColumbia University Press100% (3)

- Treating Depression in Prison Nursing HomeDokument21 SeitenTreating Depression in Prison Nursing HomeAndreea NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multimodal Treatment of Acute Psychiatric Illness: A Guide for Hospital DiversionVon EverandMultimodal Treatment of Acute Psychiatric Illness: A Guide for Hospital DiversionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health Help Seeking Among Filipinos: A Review of The LiteratureDokument15 SeitenMental Health Help Seeking Among Filipinos: A Review of The LiteratureJonie Vince SañosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health-Related Quality of Life of Chinese People With Schizophrenia in Hong Kong and Taipei: A Cross-Sectional AnalysisDokument9 SeitenHealth-Related Quality of Life of Chinese People With Schizophrenia in Hong Kong and Taipei: A Cross-Sectional AnalysisMerissa Asrina NentyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ananotaed BibliographyDokument12 SeitenAnanotaed BibliographyElvis Rodgers DenisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hoping and Coping in Recovery A Phenomenology of Emerging Adults in A Collegiate Recovery ProgramDokument18 SeitenHoping and Coping in Recovery A Phenomenology of Emerging Adults in A Collegiate Recovery ProgramBulan BulawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scholarly Paper-CrumplerDokument8 SeitenScholarly Paper-Crumplerapi-354214139Noch keine Bewertungen

- Scholarly PaperDokument6 SeitenScholarly Paperapi-430368919Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Confinement and Mental Illness in U.S Prisoners 1Dokument19 SeitenRunning Head: Confinement and Mental Illness in U.S Prisoners 1Tonnie KiamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- One Size Fits All RevisedDokument39 SeitenOne Size Fits All RevisedMark Norriel CajandabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Issue Exploratory Paper - Rough DraftDokument8 SeitenIssue Exploratory Paper - Rough Draftapi-239705788Noch keine Bewertungen

- Revised To Print ThesisDokument28 SeitenRevised To Print ThesisKhaycee GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health FacilitiesDokument11 SeitenMental Health FacilitiesMiKayla PenningsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manuscript-Fazenda de EsperanzaDokument21 SeitenManuscript-Fazenda de EsperanzaMadelaine Soriano PlaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Research Shows: NARTH's Response To The APA Claims On HomosexualityDokument4 SeitenWhat Research Shows: NARTH's Response To The APA Claims On Homosexualitybmx0Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Needs and Mental Health of Older People in 24-Hour Care Residential PlacementsDokument5 SeitenThe Needs and Mental Health of Older People in 24-Hour Care Residential PlacementspijaorenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Comparisons in Substance Abuse Recovery: Research ProposalDokument46 SeitenSocial Comparisons in Substance Abuse Recovery: Research ProposalJames ThreadgillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Mental Health Services in Latin America For People With Severe Mental DisordersDokument23 SeitenCommunity Mental Health Services in Latin America For People With Severe Mental DisordersGloria ThomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise Addiction Research PaperDokument6 SeitenExercise Addiction Research Paperzejasyvkg100% (1)

- 140.editedDokument19 Seiten140.editedTonnie KiamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misunderstanding Addiction: Overcoming Myth, Mysticism, and Misdirection in the Addictions Treatment IndustryVon EverandMisunderstanding Addiction: Overcoming Myth, Mysticism, and Misdirection in the Addictions Treatment IndustryNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017, Family Intervention in A Prison Environment A Systematic Literature ReviewDokument17 Seiten2017, Family Intervention in A Prison Environment A Systematic Literature ReviewEduardo RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calidad de Vida 03Dokument7 SeitenCalidad de Vida 03RosarioBengocheaSecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deinstitutionalization and Crime LevelsDokument28 SeitenDeinstitutionalization and Crime Levelsapi-3785090100% (1)

- Research Paper Drugs AbuseDokument4 SeitenResearch Paper Drugs Abuseafmcmuugo100% (1)

- Alcohol Consumption and Related Crime Incident in John Paul CollegeDokument17 SeitenAlcohol Consumption and Related Crime Incident in John Paul Collegejoy mesanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Promoting Workforce Strategies For Reintegrating Ex OffendersDokument19 SeitenPromoting Workforce Strategies For Reintegrating Ex Offendersaflee123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Recovery Monographs Volume Ii: Revolutionizing the Ways That Behavioral Health Leaders Think About People with Substance Use DisordersVon EverandRecovery Monographs Volume Ii: Revolutionizing the Ways That Behavioral Health Leaders Think About People with Substance Use DisordersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unlicensed Residential Programs The Next Challenge in Protecting YouthDokument34 SeitenUnlicensed Residential Programs The Next Challenge in Protecting YouthAnthony PaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- No Room at The Inn-2012Dokument28 SeitenNo Room at The Inn-2012Treatment Advocacy CenterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociocultural FactorsDokument6 SeitenSociocultural FactorsjainchanchalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relapse Prevention From Radical Idea To Common Practice 2012Dokument14 SeitenRelapse Prevention From Radical Idea To Common Practice 2012David Alejandro Londoño100% (1)

- Drug Use and Ageing PaperDokument12 SeitenDrug Use and Ageing PaperEdo Von CrnićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benefits of Lived Experience Final 1Dokument49 SeitenBenefits of Lived Experience Final 1martoNoch keine Bewertungen

- RRLDokument4 SeitenRRLMark CornejoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On Incarcerated Population - EditedDokument9 SeitenLiterature Review On Incarcerated Population - EditedKeii blackhoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Best Recovery Attitudes Paper - Final - 24714Dokument22 SeitenBest Recovery Attitudes Paper - Final - 24714Margaret MaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery: Exploring The RelationshipDokument11 SeitenPsychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery: Exploring The RelationshipmariajoaomoreiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Needs Assessment Plan PaperDokument8 SeitenNeeds Assessment Plan PaperNaomiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospice and Self-Assessed Quality of Life in The Dying: A ReviewDokument16 SeitenHospice and Self-Assessed Quality of Life in The Dying: A Reviewrohmana kusnul adzaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- RECIDIVISMDokument15 SeitenRECIDIVISMAnonymous OP6R1ZSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review Social IsolationDokument7 SeitenLiterature Review Social Isolationaflswnfej100% (1)

- Research 3Dokument8 SeitenResearch 3Alexandra RiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hooked: A concise guide to the underlying mechanics of addiction and treatment for patients, families, and providersVon EverandHooked: A concise guide to the underlying mechanics of addiction and treatment for patients, families, and providersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Racial Differences in Self-Reports of Sleep Duration in A Population-Based StudyDokument8 SeitenRacial Differences in Self-Reports of Sleep Duration in A Population-Based StudyRivhan FauzanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family-Alcohol ReviewDokument19 SeitenFamily-Alcohol ReviewErma89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Emerging Issues in Geriatric Care: Aging and Public Health PerspectivesDokument6 SeitenEmerging Issues in Geriatric Care: Aging and Public Health PerspectiveslynhareeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health MedicationsDokument1 SeiteMental Health MedicationsAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- WS 2 DisposalDokument1 SeiteWS 2 DisposalAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Illicit Drug WebpagesDokument1 SeiteIllicit Drug WebpagesAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- WS 1 PerscriptionsDokument1 SeiteWS 1 PerscriptionsAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Costs To SocietyDokument1 SeiteCosts To SocietyAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Information SheetDokument2 SeitenInformation SheetAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Res AgreementDokument1 SeiteRes AgreementAdrianaZarate100% (1)

- WS I FoodDokument1 SeiteWS I FoodAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

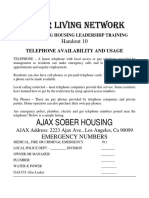

- TelephoneDokument1 SeiteTelephoneAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- FoodDokument1 SeiteFoodAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trinty House RulesDokument2 SeitenTrinty House RulesAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample App 1pDokument1 SeiteSample App 1pAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sober Living Network: Household and Cleaning SuppliesDokument1 SeiteSober Living Network: Household and Cleaning SuppliesAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Protections FINALDokument2 SeitenLegal Protections FINALAdrianaZarate0% (1)

- Occupancy GuidelinesDokument1 SeiteOccupancy GuidelinesAdrianaZarate100% (1)

- SLNetwork Standard Home Rev10!01!2011Dokument8 SeitenSLNetwork Standard Home Rev10!01!2011AdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- FH Limitations.Dokument1 SeiteFH Limitations.AdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- DSS DefinitionsDokument1 SeiteDSS DefinitionsAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Model ScaleDokument1 SeiteSocial Model ScaleAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grievance Policies2-05Dokument1 SeiteGrievance Policies2-05AdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Onepage Check ListDokument1 SeiteOnepage Check ListAdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

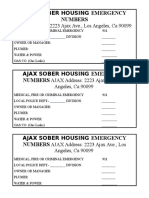

- Emergency #Dokument2 SeitenEmergency #AdrianaZarateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parts of The Guitar QuizDokument2 SeitenParts of The Guitar Quizapi-293063423100% (1)

- "Written Statement": Tanushka Shukla B.A. LL.B. (2169)Dokument3 Seiten"Written Statement": Tanushka Shukla B.A. LL.B. (2169)Tanushka shuklaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade Up CurrentsDokument273 SeitenGrade Up CurrentsAmiya RoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mechanical Engineering Research PapersDokument8 SeitenMechanical Engineering Research Papersfvfzfa5d100% (1)

- BZU Ad 31 12 12Dokument15 SeitenBZU Ad 31 12 12Saleem MirraniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Probet DocxuDokument12 SeitenProbet DocxuAbuuAwadhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dirt Bikes Financial and Sales DataDokument7 SeitenDirt Bikes Financial and Sales Datakhang nguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- ShindaiwaDgw311DmUsersManual204090 776270414Dokument37 SeitenShindaiwaDgw311DmUsersManual204090 776270414JGT TNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scrabble Scrabble Is A Word Game in Which Two or Four Players Score Points by Placing Tiles, EachDokument4 SeitenScrabble Scrabble Is A Word Game in Which Two or Four Players Score Points by Placing Tiles, EachNathalie Faye De PeraltaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prayer Points 7 Day Prayer Fasting PerfectionDokument4 SeitenPrayer Points 7 Day Prayer Fasting PerfectionBenjamin Adelwini Bugri100% (6)

- The 296 Proposed New (Baseline & Monitoring) Methodologies Sent To The Executive BoardDokument264 SeitenThe 296 Proposed New (Baseline & Monitoring) Methodologies Sent To The Executive Boarddjuneja86Noch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Example of Intensive Pronoun in SentenceDokument2 Seiten5 Example of Intensive Pronoun in SentenceRaúl Javier Gambe CapoteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Triple Net Lease Research Report by The Boulder GroupDokument2 SeitenTriple Net Lease Research Report by The Boulder GroupnetleaseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Investor Presentation (Company Update)Dokument17 SeitenInvestor Presentation (Company Update)Shyam SunderNoch keine Bewertungen

- RightShip Inspections Ship Questionaire RISQ 3.0Dokument207 SeitenRightShip Inspections Ship Questionaire RISQ 3.0Philic Rohit100% (1)

- HCM-C Ng-Hòa. 3kDokument300 SeitenHCM-C Ng-Hòa. 3kTrí PhạmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Choco Cherry BonbonDokument2 SeitenChoco Cherry BonbonYarina MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resonant Excitation of Coherent Cerenkov Radiation in Dielectric Lined WaveguidesDokument3 SeitenResonant Excitation of Coherent Cerenkov Radiation in Dielectric Lined WaveguidesParticle Beam Physics LabNoch keine Bewertungen

- D2-S1 C Harmony in The Human Being July 23Dokument20 SeitenD2-S1 C Harmony in The Human Being July 23padmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Partnership Liquidation May 13 C PDFDokument3 SeitenPartnership Liquidation May 13 C PDFElla AlmazanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Auto Loan Application Form - IndividualDokument2 SeitenAuto Loan Application Form - IndividualKlarise EspinosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal Inggris PrintDokument3 SeitenSoal Inggris Printmtsn1okus ptspNoch keine Bewertungen

- ch27 Matrices and ApplicationsDokument34 Seitench27 Matrices and Applicationschowa fellonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intensive Care Fundamentals: František Duška Mo Al-Haddad Maurizio Cecconi EditorsDokument278 SeitenIntensive Care Fundamentals: František Duška Mo Al-Haddad Maurizio Cecconi EditorsthegridfanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Holidays Homework 12Dokument26 SeitenHolidays Homework 12richa agarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurczyk Et Al-2015-Journal of Agronomy and Crop ScienceDokument8 SeitenJurczyk Et Al-2015-Journal of Agronomy and Crop ScienceAzhari RizalNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPL201201H251301 EN Brochure 3Dokument11 SeitenRPL201201H251301 EN Brochure 3vitor rodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course: Business Communication Course Code: COM 402 Submitted To: Mr. Nasirullah Khan Submission Date: 12Dokument18 SeitenCourse: Business Communication Course Code: COM 402 Submitted To: Mr. Nasirullah Khan Submission Date: 12Wahaj noor SiddiqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- NM Rothschild & Sons (Australia) LTD. V Lepanto Consolidated Mining CompanyDokument1 SeiteNM Rothschild & Sons (Australia) LTD. V Lepanto Consolidated Mining Companygel94Noch keine Bewertungen

- Essay On Stamp CollectionDokument5 SeitenEssay On Stamp Collectionezmt6r5c100% (2)