Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Applying PMBOK To Shutdowns

Hochgeladen von

Vanessa Pajares LanciatoOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Applying PMBOK To Shutdowns

Hochgeladen von

Vanessa Pajares LanciatoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Applying PMBOK to Shutdowns,

Turnarounds and Outages

Bernard Ertl

Vice President,

A TURNAROUND-SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT

METHODOLOGY

Abstract

InterPlan Systems Inc.

The discipline of project management enjoys

different states of maturity across different industries,

the construction industry probably enjoying the

greatest maturity in this field while

Turnarounds have a distinctive character of their own and cannot

the software development/IT industry

is probably enjoying the greatest

be managed as if they were just another sort of Engineering,

growth in maturity at this time. In

Procurement and Construction (EPC) project; a turnaroundthe process industries the maturity of

specific methodology of management is needed. Drawing on

the project management discipline as

the philosophy of the Project Management Institutes Guide to

regards turnarounds is still very poor,

stagnant at best.

the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) the

author reviews the special problems presented by process plant

There appears to be little if any

development of, or dialogue about,

the discipline within the field.

Turnaround failures (budgets blown by millions

of dollars, target dates missed by days) are still as

prevalent as ever. The same mistakes are being

repeated over and over. The main problem is that

turnaround managers continue to treat turnarounds

as if they were Engineering, Procurement and

Construction (EPC) civil projects and hence apply an

EPC-centric project management methodology.

turnarounds and also their particular management needs.

FOREWORD

hutdowns, turnarounds and outages

All the major process industries (refining,

petrochemicals, power generation, pulp

and paper, etc.) have their own nomenclature for

maintenance projects. For the purposes of this

document, turnaround is intended to encompass

all types of industrial projects for existing process

plants including

Inspection and testing

Shutdowns

Emergency outages

De-bottlenecking projects

Revamps

Catalyst regeneration, etc.

i.e. all those instances when an operating plant must

be shut down until the work is completed and then

restarted, thus turning around the unit or plant. In

this paper turnaround is also intended to refer to

the entire span from pre-turnaround preparations,

to shutdown, to execution and finally to start-up.

One of the greatest challenges to turnaround

managers is realising that turnarounds are different

from EPC projects. They have their own unique

characteristics and demands. They require a specialised

project management methodology. This document

is intended to spark a dialogue for developing a

turnaround-specific management methodology.

Background

The Project Management Institute (PMI) has

published A Guide to the Project Management Body of

Knowledge (PMBOK) which identifies and describes

the subset of the project management discipline that

is applicable to most projects most of the time. It

maintenance & asset management vol 20 no 3 19

Applying PMBOK to Shutdowns,

Turnarounds and Outages

provides a loose guideline for structuring a project

management methodology, and describes its

primary purpose as being

....to identify and describe that subset of the PMBOK

that is generally accepted. Generally accepted means

that the knowledge and practices described are

applicable to most projects most of the time, and that

there is widespread consensus about their value and

usefulness. Generally accepted does not mean

that the knowledge and practices described are or

should be applied uniformly on all projects; the

project management team is always responsible for

determining what is appropriate for any given project.

It is up to turnaround managers to evaluate the

applicability to turnarounds of their specific

project management methodology. Many

turnaround managers do not have a formal

background in project management and have

never studied the PMBOK. As a result, there has

been little discussion in professional circles of the

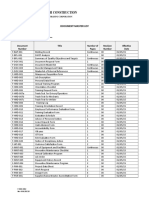

PROJECT

1.

Usually well-defined scope, from:

a. drawings

b. specifications

c. contracts

d. permits, memos, etc.

TURNAROUND

1.

Usually loosley defined scope, from:

a. past turnaround experience

b. inspection reports

c. operations requests

d. historical estimates

2. Scope is static. Few changes occur

during execution.

2. Scope is dynamic. Many changes occur as

inspections are made.

3. Can be planned and scheduled well in

advance of the project.

3. Planning and scheduling cannot be finalized

until the scope is approved, generally near the

shutdown date.

4. Projects are organized around cost

codes / commodities.

4. Turnarounds are work order based.

5. Generally do not require safety permits

to perform work.

5. Turnaround work requires extensive

permitting every shift.

6. Manpower staffing requirements usually do

not change.

6. Manpower staffing requirements change

during execution due to scope fluctuations.

7. Project schedules can be updated either

weekly or monthly.

7. Turnaround schedules must be updated every

shift, daily.

8. Projects measure time in days, weeks

and months.

8. Turnarounds measure time in hours or

shifts.

9. Project scope is usually all mandatory.

9. Turnaround scope is flexible. Usually a

large percentage of work can be postponed

to a later window of opportunity if

necessary.

10. Project schedules are uncompressed.

Schedule acceleration can be used to

correct slippages in the critical path.

10. Turnaround schedules are compressed.

There may be little or no opportunity to

correct the critical path by accelerating the

schedule.

Table 1. EPC projects vs. turnarounds

20 maintenance & asset management vol 20 no 3

proper application of the PMBOK to a turnaroundspecific management methodology.

Most turnaround managers employ an EPC-centric

project management approach to turnarounds. In

order to analyse the applicability of this approach,

we first need to understand the important

differences between turnarounds and EPC projects.

Then we shall have the proper basis for evaluating

a turnaround-centric project management

methodology in accordance with the PMBOK.

Important differences between

turnarounds and EPC projects

There are significant differences between

turnarounds and EPC projects (see Table 1), which

are worth exploring.

Because the scope is only partially known when

execution begins, turnarounds demand much stricter

scope management controls. A constantly changing

scope (and schedule) means that the baseline

schedule is a useless measuring stick. As it is the

entire basis for measuring and tracking EPC project

performance, it is clear that a different paradigm is

required for turnarounds.

A changing schedule and changing manpower

requirements make resource levelling, a popular tool

for EPC projects, counter-productive for turnarounds.

This issue is explored in greater depth in the Resource

Levelling Vs. Critical Mass white paper which can be

found on our website (www.interplansystems.com/

html-docs/resource-leveling-critical-mass.html).

The compressed work basis for executing turnarounds

means that all team members have less time to

analyse and react to changing priorities. Problems that

go unchecked can significantly affect the likelihood

of reaching time and budget goals. As a consequence,

there is a much greater need to use the schedule to

drive the project execution (whereas it is sometimes

used mostly as a contractual tool in EPC projects). It

is critical for all schedule and progress information to

be highly visible, timely, comprehensive and accurate.

With these distinctions in mind, we can now explore

the tenets of the PMBOK and start working towards a

turnaround-specific project management methodology.

Applying PMBOK to Shutdowns,

Turnarounds and Outages

PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT

One of the greatest challenges in a turnaround is

scope management. This is true for virtually all

phases of scope management as outlined by the

PMBOK, viz. Scope Planning, Scope Definition,

Scope Verification and Scope Change Control.

approved budget or authorisation for expenditure

(AFE). If not, either the scope should be culled

where possible (or failure to meet the budget will be

pre-determined) or the budget should be adjusted to

reflect the plan (not always politically viable).

Scope change control

Scope planning, definition and

verification

Unlike EPC projects which usually have a well

defined scope established with long lead times

before the project execution phase it is common

for turnaround scopes to be changing up to the last

minute before project execution. There are several

factors contributing to this

Market conditions (plant profitability)

can cause variability in considerations

for the budget (requiring scope

adjustments), window (squeezing or

relaxing the time frame available for

executing the project) and start date

(which may affect the decisions on what

scope to include, the ability to plan

the work, or material availability).

Planning input is usually derived with

input from Operations, Inspection, Safety,

etc., and Operations may continue

to identify potential scope for the

turnaround until the last minute.

The availability of specialised

tools, materials, equipment and/or

resources may affect decisions on how

to approach portions of the scope

(i.e. plans may need adjusting to

accommodate a different method or

scenario to accomplish the same goal).

One result of this is that turnaround budgets

are rarely based upon a complete, detailed plan.

They are often based upon conceptual estimates,

extrapolations of past turnarounds, or on incomplete

planned scopes that are compensated with a large

allowance for contingencies, and it is therefore

necessary to review the cost estimate for the final

approved scope and make sure it is covered by the

In a turnaround, the scope will change - sometimes

dramatically. As equipment is opened, cleaned

and inspected the extent of required repairs can be

determined, planned, costed and either approved

or tabled for a future window of opportunity. Every

add-on to the schedule should be processed with

a defined procedure for evaluation/approval.An

additional challenge is presented in companies

where the existing culture allows operators to direct

work crews (or get supervisors to direct work crews)

to perform work that for one reason or another was

not included in the approved project scope. The

only solution is to change the culture to respect the

defined procedure for add-on approval. Operators

and supervisors or superintendents must buy in to the

add-on approval procedure and field hands must be

directed to work only on approved scope as directed

by their supervisors. Where this is not possible (or

there is a work in progress) it is imperative to at least

document and account for these unapproved jobs,

where performed, so that progress tracking (earned

value) may give a meaningful impression of the

productivity of the field work.

Operators and supervisors or superintendents must buy

in to the add-on approval procedure and field hands

must be directed to work only on approved scope as

directed by their supervisors.

Management needs to exercise care when evaluating

add-on repair scope, in order to ensure that existing

resources, productivity and time can accommodate

the work (where the repair scope is not operationally

critical or safety critical). Management can end up in

a position of balancing the impact of add-on repair

work against the culling of original scope where

resources become constrained on work that is non-

maintenance & asset management vol 20 no 3 21

Applying PMBOK to Shutdowns,

Turnarounds and Outages

critical (from both a time and operational or safety

point of view).

It is desirable to classify scheduled or progressed

activities according to two main criteria, viz.

(a)

and (b)

Approved Scope

Unapproved Scope

Cancelled Scope

Original Scope

Add-On Scope

PROJECT TIME MANAGEMENT

One of the most obvious signs of the low maturity

in turnaround project management is the state of

the planning and scheduling that is intended to

form the foundation of the management process. A

successful turnaround management methodology

must set a high standard for the planning and

scheduling to be successful.

Because of the compressed nature of turnarounds,

there is a very small window available for recording

and processing information on progress in order

to generate updated schedules for the next shift.

The greater the detail in the activity definition, the

less thinking or guesswork is involved in assigning

progress to the defined tasks.

Activities must be clearly defined, and should be

measurable. This means anyone should be able to

determine whether a particular activity (as defined) is

in progress, or completed. Activities must be defined

every time there is a break or change in work content,

or changes in the work crew.

Scheduling

It is of paramount importance to understand that

unlike EPC projects where a baseline schedule

is often used as a firm contractual commitment

a turnaround schedule should be considered

a guideline tool to drive the execution of the

work. This understanding is fundamental

to developing a successful turnaround

management methodology.

It is of paramount importance to understand that a turnaround

schedule should be considered a guideline tool to drive the

execution of the work. This understanding is fundamental to

developing a successful turnaround management methodology.

Activity definition

The planning of activities that are overly broad

in scope is one of the biggest obstacles to using a

schedule for any meaningful purpose. They

are difficult to estimate with confidence,

can mask details that the planner

neglected to consider,

preclude a detailed critical path

analysis where more detail may

allow refinements in the logic,

detract from the accuracy of

progress estimation (estimating

% complete is more difficult).

22 maintenance & asset management vol 20 no 3

Turnaround managers have a lot of

discretion with regard to scope management

in schedules. While there will be portions

of the scope aside from the critical path

work that must be executed within the

instant project, a significant portion of the scope

may usually be postponed to future turnarounds

or maintenance opportunities. As priorities

shift, depending upon the scope of add-on repair

work and resource constraints, managers need

a turnaround schedule that offers flexibility in

managing the non-critical work.

Baseline schedules (other than for critical and

near-critical paths) are meaningless for turnarounds

once they start. For turnarounds, it is expected that

as inspections are performed, a changing scope

(and therefore priorities for constrained resources

or non-time-critical work) and often poor schedule

compliance (due to unavoidable circumstances)

will force the schedule for non-time-critical work to

change from update to update.

Applying PMBOK to Shutdowns,

Turnarounds and Outages

Because of the dynamic nature of turnarounds it

can be counter-productive to employ soft logic

and resource levelling schemas that smooth

the schedule. Both techniques are designed to

produce a static plan for execution that is not

practical for turnarounds. Soft logic will necessitate

constant time-consuming changes and updates to

maintain a meaningful schedule once deviations

from the schedule occur (and this is expected in

a turnaround). Resource levelling schemas that

alter a hard logic schedule will introduce multiple

problems within a turnaround context. (See the

white paper Resource Levelling or Critical Mass? on our

website: www.interplansystems.com/html-docs/

resource-leveling-critical-mass.html).

It is instead preferable to maintain a schedule for

critical and near-critical path analysis and to allow

field supervision discretion in directing their crews

on non-time-critical work according to changing

priorities and circumstances. At every update

turnaround managers should monitor progress

trends, productivity/earned value and scheduled

resource requirements, to ensure that sufficient time

and resources are available to complete the non-timecritical work within the span of the critical path.

PROJECT COST MANAGEMENT

Turnarounds are notorious for over-running the

budget. Part of the problem, as mentioned earlier

in the Scope Planning section, is that budgets are

rarely based upon the detailed plans and estimates

for the scope. Many turnarounds have failure

predetermined! Should budgets be based upon a

detailed plan (or at least cover the estimate for it)

turnaround managers have a reasonable basis for

managing costs according to the formula used in

EPC projects, as laid out by the PMBOK, viz.

influencing factors that create

changes to the cost baseline to ensure

that changes are agreed upon,

determining that the cost

baseline has changed,

managing the actual changes

when and as they occur.

At the end of a turnaround, the final scope of the

execution usually encompasses several categories of

work, viz.

known scope (planned or estimated)

anticipated repairs (may or may not

have been planned or estimated)

unanticipated repairs (not

planned or estimated)

unauthorised work (not

planned or estimated)

cancelled work (planned or estimated

but culled during execution).

So, prior to execution, the turnaround manager may

have a set budget covering known scope, anticipated

repairs and some contingency allowance to cater

for possible remaining items. Because most indirect

costs (though not necessarily material costs)

are keyed off the direct labour costs, the key to

successful cost control in a turnaround is execution

control (keeping resources productive) and scope

management (balancing add-ons against non-critical

work).

Earned value management

In most cases, it is very difficult to obtain a

meaningful earned value analysis in a turnaround.

There are several problems that conspire to frustrate

the system:

The process for capturing and

approving actual hours usually lags

behind the progress updates by at

least one shift, if not two or three.

The application of the correct work order

and cost code number on timesheets is poor

Unauthorised work is charged to existing

work orders and cost codes but not

captured for planning and estimating.

Where earned value analysis is conducted, it may be

most meaningful to compare numbers analysed by

resource type instead of by work order or cost code. In

this fashion, managers may have some measure of the

productivity of the resource relative to the schedule.

maintenance & asset management vol 20 no 3 23

Applying PMBOK to Shutdowns,

Turnarounds and Outages

PROJECT QUALITY MANAGEMENT

According to the PMBOK, project quality

management entails several aspects, viz.

quality planning,

quality assurance,

quality control.

Of these, quality assurance and quality control are

usually well defined (and in some cases, government

regulated) for safety concerns in turnarounds.

Quality planning, on the other hand, is an issue

that is usually poorly addressed. It is recommended

that organisations employ a system for capturing

and improving plans and estimates for recurring

jobs from turnaround to turnaround. This entails

benchmarking during execution and a follow up

review post-execution to update the system. Too

often, the follow up review never occurs and it is left

to chance that the planner will remember necessary

details the next time a turnaround involving the

same unit is planned.

In many cases where the preparation time for

planning a turnaround is compressed or inadequate

there is a better than average chance that turnaround

plans based upon templates (or historical plans)

will suffer from cut and paste syndrome and not

receive due consideration for customising to the

instant situation. The best solution for mitigating

these problems is to use a planning system like

eTaskMaker.

PROJECT HUMAN RESOURCE

MANAGEMENT

Most turnarounds involve managing a large contract

work force to execute the project. The dynamics

of organisational planning and staffing are usually

well understood. The industry is mature enough for

project roles and responsibilities to be well defined.

There is a mature support industry of specialised and

general contractors to supply the necessary human

resources.

Probably the greatest challenge that turnarounds

present in comparison with EPC projects is the

24 maintenance & asset management vol 20 no 3

management of the human resource. This is true at a

macro (overall staffing levels) and micro (delegation

of work to labour pools) level.

Most turnarounds staffing levels can be represented

with a bell curve. Staffing levels for specialised skills

are increased slowly as units are blinded and vessels

opened. Staffing levels are reduced as repairs are

completed near the end of the turnaround. Managers

should analyse staffing levels versus schedule

requirements frequently (in some cases daily) to

ensure that sufficient manpower is available to

complete the bulk of non-time-critical work within

the span of the critical path while also demobilising

excess manpower to control costs.

It is critical to the successful execution of a

turnaround for field supervisors and superintendents

to foster a co-operative teamwork spirit with

regards to managing the existing labour pool.

Where supervisors and superintendents are held

accountable for meeting individual schedule and

progress goals, competition for (and hoarding of)

skilled labour can occur and jeopardise the project

success. Supervisors and superintendents should

bear equal responsibility for meeting the overall

schedule and progress goals.

PROJECT COMMUNICATIONS

MANAGEMENT

One of the single most important aspects

of successful turnaround management is

communication. Because of the compressed time

frame, there is less time available to everyone in the

turnaround team to overcome the problems caused

by poor communication.

Communications planning

Many turnaround organisations do not have a

communications plan outlining team members

information needs, delivery schedule and

distribution system. Ad hoc reporting does not

provide the necessary foundation for maintaining

high visibility of the project to all stakeholders. A

proper communications plan should include

Applying PMBOK to Shutdowns,

Turnarounds and Outages

Executive Management (summary

schedule, progress) liaising with

Turnaround Management (scope,

schedule, progress, manpower)

Planning/Scheduling (scope,

schedule, progress) liaising with

Inspection (schedule, progress)

Operations (scope, schedule,

progress) liaising with Safety (scope,

schedule [permit requirements])

Warehouse (scope, schedule)

Information distribution

Since turnarounds are so dynamic, information

needs to be updated every shift if visibility and

control are to be maintained. In order to help

field supervision stay on top of changing schedule

priorities, it is recommended that complete schedule

updates be initiated just before the end of every shift

so that they may be disseminated to the field at the

start of the next shift. Without this, the schedule will

quickly become meaningless as a tool for managing

and driving the project scope and execution.

Stakeholders in turnarounds are always pressed

for time. It is recommended that all disseminated

information conform to standard report formats,

familiarity with which will enable team members

to read and digest the information quickly and will

minimise the potential for misinterpretations.

PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT

Turnarounds usually entail a high degree of risk.

Because the scope of work is only partially known,

managers must prepare for the possibility that the

effort to clean or repair equipment may exceed

estimates and expectations when the equipment is

opened and inspected for the first time.

It is recommended that risk analysis be considered for

critical and near-critical path work in the schedule

because such work carries the greatest likelihood of

affecting timely completion.

In general, it is not practical to attempt to model all

potential risks within the project schedule. There are

virtually infinite possibilities for required repairs on

the more complicated pieces of plant equipment like

compressors, heaters/furnaces, towers, etc.

It is recommended that risk analysis be considered

for critical and near-critical path work in the

schedule because such work carries the greatest

likelihood of affecting timely completion. Managers

must balance the cost of maintaining any specialised

parts or materials for identified risks against the cost

of a possible schedule delay should such parts or

materials need to be procured at the last minute.

Performance reporting

A turnaround project should not be analysed in the

same manner as an EPC project. Their dynamics and

characteristics are different. Baseline schedules that

drive EPC project analysis are relatively meaningless

for turnarounds after the first couple of shifts.

Turnarounds require specialised metrics for analysis, e.g.

Summary progress attainment curves for

measuring, tracking and trending against

earned progress.

Critical mass

(see our website www.interplansystems.

com/turnaround-project-managementprimer/critical-mass.html).

CONCLUSION

Turnarounds are very challenging and dynamic

high performance projects. They have many unique

characteristics that differentiate them from other

types of projects. The EPC-centric approach to

project management does not work very well for

managing turnarounds.

It is hoped that this paper may prompt the reader

to consider employing a turnaround-specific

methodology for managing turnarounds. Considering

the stakes involved, it is high time that industry

adopted a more mature approach to this task.

maintenance & asset management vol 20 no 3 25

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- RONDS Product Catalog: Wireless Machine Monitoring SolutionsDokument12 SeitenRONDS Product Catalog: Wireless Machine Monitoring SolutionsVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Texto 2 PDFDokument1 SeiteTexto 2 PDFVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Eddy Probe Systems PDFDokument44 SeitenEddy Probe Systems PDFVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Introduction To PeakvueDokument55 SeitenIntroduction To PeakvueAhmed Nazeem100% (4)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Texto PDFDokument1 SeiteTexto PDFVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- SKF4560 - E Rolling Bearings in Industrial GearboxesDokument195 SeitenSKF4560 - E Rolling Bearings in Industrial GearboxesVanessa Pajares Lanciato100% (6)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- TextoDokument1 SeiteTextoVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shell Alvania Greases EP: High-performance extreme pressure greaseDokument2 SeitenShell Alvania Greases EP: High-performance extreme pressure greaseVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- WEG w21 Three Phase Motor Indian Market 013 Brochure EnglishDokument36 SeitenWEG w21 Three Phase Motor Indian Market 013 Brochure EnglishluiggichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- 4560 E 2 TCM 12-73081 PDFDokument78 Seiten4560 E 2 TCM 12-73081 PDFVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- WEG w21 Three Phase Motor Indian Market 013 Brochure EnglishDokument36 SeitenWEG w21 Three Phase Motor Indian Market 013 Brochure EnglishluiggichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section II - Basic Vibration TheoryDokument85 SeitenSection II - Basic Vibration Theoryagiba100% (7)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- AF04008 Motor MS Estrategia de MantenimientoDokument18 SeitenAF04008 Motor MS Estrategia de MantenimientoVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- JM02012 - Time Domain Analysis - DesbloqueadoDokument12 SeitenJM02012 - Time Domain Analysis - DesbloqueadoVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Optibelt Product Catalog PDFDokument172 SeitenOptibelt Product Catalog PDFVanessa Pajares LanciatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- GS02003 Root Cause Analysis TCM 12-75931Dokument16 SeitenGS02003 Root Cause Analysis TCM 12-75931Vanessa Pajares Lanciato100% (1)

- Using Excel For Qualitative Data AnalysisDokument5 SeitenUsing Excel For Qualitative Data Analysiscrexo000100% (1)

- 1Z0 062 Oracle Database 12cinstallation and Administration PDFDokument146 Seiten1Z0 062 Oracle Database 12cinstallation and Administration PDFankur singhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Time Series Using Stata (Oscar Torres-Reyna Version) : December 2007Dokument32 SeitenTime Series Using Stata (Oscar Torres-Reyna Version) : December 2007Humayun KabirNoch keine Bewertungen

- SCTFDokument17 SeitenSCTFShurieUNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Python For ML - Recursion, Inheritence, Data HidingDokument19 SeitenPython For ML - Recursion, Inheritence, Data Hidingjohn pradeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Magic 3d Easy View Manual Es PDFDokument32 SeitenMagic 3d Easy View Manual Es PDFAngel Santiago Silva HuamalianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- GRCDP00696190000029942Dokument2 SeitenGRCDP00696190000029942Gokul KrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lehmann - 1981 - Algebraic Specification of Data Types - A Synthetic Approach PDFDokument43 SeitenLehmann - 1981 - Algebraic Specification of Data Types - A Synthetic Approach PDFLógica UsbNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Dangling Pointer Memory Leak in CDokument4 SeitenDangling Pointer Memory Leak in CNaga Pradeep VeerisettyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 Document MasterlistDokument3 Seiten01 Document MasterlistHorhe SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- (B) Ruan D., Huang C. (Eds) Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Information - Granulation Theory (BNUP, 2000) (T) (522s)Dokument522 Seiten(B) Ruan D., Huang C. (Eds) Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Information - Granulation Theory (BNUP, 2000) (T) (522s)Mostafa MirshekariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Access the new Azure Portal and view subscription information in the dashboardDokument2 SeitenAccess the new Azure Portal and view subscription information in the dashboardSaikrishNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- C Book IndexDokument4 SeitenC Book IndexAtinderpal SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 6Dokument3 SeitenAssignment 6api-350594977Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6-Multimedia Streams SynchronizationDokument38 SeitenChapter 6-Multimedia Streams SynchronizationhubillanthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asist. Univ.: Matei StoicoviciDokument10 SeitenAsist. Univ.: Matei StoicoviciAndreea9022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Planning Advertising Campaign to Maximize New CustomersDokument4 SeitenPlanning Advertising Campaign to Maximize New CustomersAdmin0% (1)

- Module 5 - Repetition Control StructureDokument53 SeitenModule 5 - Repetition Control StructureRegie NojaldaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Introduction To Optimal Control Applied To Disease ModelsDokument37 SeitenAn Introduction To Optimal Control Applied To Disease ModelsMohammad Umar RehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- How to setup Bristol Audio Synthesis with 64 StudioDokument5 SeitenHow to setup Bristol Audio Synthesis with 64 StudiobobmeanzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ResumeDokument3 SeitenResumeRafi ShaikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Final windows in Smartforms to display total page counts by ship-to-partyDokument6 SeitenUsing Final windows in Smartforms to display total page counts by ship-to-partypanirbanonline3426Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pei-Bai Zhou - Numerical Analysis of Electromagnetic FieldsDokument418 SeitenPei-Bai Zhou - Numerical Analysis of Electromagnetic FieldsTienRienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nota de Aplicacion - PicoPower BasicsDokument7 SeitenNota de Aplicacion - PicoPower Basicsgusti072Noch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Real Time ClockDokument44 SeitenReal Time Clocksubucud100% (1)

- Data warehouse roles of education in delivery and mining systemsDokument4 SeitenData warehouse roles of education in delivery and mining systemskiet eduNoch keine Bewertungen

- L6 Systems of InequalitiesDokument25 SeitenL6 Systems of InequalitiesFlorence FlorendoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDFDokument19 SeitenPDFपोटैटो शर्मा0% (1)

- Mom PDFDokument8 SeitenMom PDFThug LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Worksheet BFH - SolutionDokument7 SeitenWorksheet BFH - SolutionAmogh D GNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (78)

- The Millionaire Fastlane, 10th Anniversary Edition: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeVon EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane, 10th Anniversary Edition: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (85)