Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Preoperative Assessment

Hochgeladen von

1234chocoCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Preoperative Assessment

Hochgeladen von

1234chocoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ANAESTHESIA II

Anaesthesia II

Preoperative assessment

F J Garca-Miguel, P G Serrano-Aguilar, J Lpez-Bastida

Although anaesthetic and surgical procedures should be individualised for every patient, in practice many preoperative

protocols and routines are used generally. In this article, we aim to emphasise: why preoperative assessment is

important; how it should be done, and by whom; what can be expected; and the importance of test selection based on

patients needs and on scientific evidence of effectiveness. We outline the roles of preoperative medical assessment

in otherwise healthy patients. Clinical history, preoperative questionnaires, physical examination, routine tests,

individual risk-assessment, and fasting policies are investigated by review of published work. Cost of routine

preoperative assessment, the anaesthetists legal responsibility, and patients views in the preoperative process are

also considered. A thorough clinical preoperative assessment of the patient is more important than routine

preoperative tests, which should be requested only when justified by clinical indications. Moreover, this practice

eliminates unnecessary cost without compromising the safety and quality of care. Education and training of medical

doctors should be more scientifically guided, emphasising the relevance of effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness in

clinical decision-making and complemented by audit.

Preoperative assessment is the clinical investigation that

precedes anaesthesia for surgical or non-surgical

procedures, and is the responsibility of the anaesthetist.

The aims of preoperative assessment are to reduce the

risks associated with surgery and anaesthesia, to increase

the quality (thus decreasing the cost) of peroperative care,

to restore the patient to the desired level of function, and

to obtain the patients informed consent for the

anaesthetic procedure.1 This assessment should rely on

the rational use of information from the patients medical

records, clinical interview, physical examination, and

some additional tests.2 Traditionally, a preoperative

consultation with the anaesthetist has facilitated these

goals. Nevertheless, the process of preoperative

assessment has undergone major changes. The increasing

number of day-case surgery procedures has affected the

way in which the anaesthetist assesses patients

preoperatively. Overuse and unexplained variations of

tests for preoperative assessment have been extensively

documented.312 Although most institutions have

established recommendations for the use of laboratory

tests, information is scarce about the ability of such

guidelines to modify and improve the selection of

preoperative tests. It is important to investigate costeffectiveness and efficiency while providing the best

care.35 This article is an update on recent management

issues in preoperative assessment. Our aims are: (1) To

review and assess the evidence related to the health-care

benefits of preoperative assessment; (2) to offer a

reference framework for the practice of preanaesthetic

assessment; and (3) to stimulate research.

Lancet 2003; 362: 174957

Department of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, Hospital General

de Segovia, Segovia, Spain (F J Garca-Miguel PhD); and Department

of Planning and Evaluation, Servicio Canario de Salud, Canary

Islands, Spain (P G Serrano-Aguilar PhD, J Lpez-Bastida PhD)

Correspondence to: Dr F J Garca-Miguel, Department of

Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, Hospital General de Segovia,

Crta Avila s/n 40002, Segovia, Spain

(e-mail: fgarcia@hgse.sacyl.es)

Preoperative medical assessment

A preoperative assessment is believed to be a basic

element of anaesthetic care. However, we were unable to

find any controlled trials on the clinical effect of provision

of a preanaesthetic review of medical records, or an

adequate physical examination.2 The aim of assessment of

patients before anaesthesia and surgery is to improve the

outcome, by identifying potential anaesthetic difficulties,

identifying existing medical conditions, improving safety

by assessing and quantifying risk, allowing planning of

peroperative care, providing the opportunity for

explanation and discussion, and allaying fear and anxiety.

Good preoperative assessment will help to reduce costs

and increase efficiency of operative theatre time.13

Search strategy

We searched for trials in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and HealthSTAR

databases. The databases of the UK Centre for Reviews and

Dissemination (DARE and NHS economic evaluation

database) and the Cochrane Collaboration (The Cochrane

Library) were also used. The search included all published

articles regardless of the language. Terms used in the search

were preoperative evaluation, pre-anaesthetic assessment,

preoperative test, surgical risk, and informed consent. All

relevant studies concerning chest radiograph,

electrocardiogram (ECG), laboratory tests, and legal aspects

were retrieved. Information on preoperative test

recommendations for elective surgery in asymptomatic

patients was mainly obtained from systematic reviews

published for International Health Technology Assessment

Agencies.612 To complete the review on the specific topic of

preoperative testing we accepted the work done by Munro

and colleagues6 and by the National Institute for Clinical

Excellence (NICE)12 as the most comprehensive, and we

extended the search strategy used by Munro and colleagues

from 1997 to 2003. The definition used in this paper for

routine preoperative testing is that of tests ordered for

asymptomatic, apparently healthy individuals, in the absence

of any specific clinical indication, to identify conditions

undetected by clinical history and examination.6

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

1749

ANAESTHESIA II

Panel 1: Preoperative questionnaire for adults13

Panel 2: Preoperative questionnaire for children13,23

Have you ever suffered from any of the following? (if yes,

please give details)

Heart disease or any sort

Chest pain, palpitations, or blackouts

High blood pressure

Rheumatic fever

Asthma, bronchitis, or other chest disease

Breathless on exertion at night

Diabetes or sugar in the urine

Kidney or urinary trouble

Convulsions or fits

Anaemia or other blood disorders

Bruising or bleeding problems

Blood clots in the legs or lungs

Jaundice (yellowness)

Indigestion or heartburn

Any other serious illness

1. Has your child had good growth, development, and

exercise tolerance?

2. Has your child been admitted to or frequently attended

hospital?

3. Has your child attended a doctor in the past 4 weeks?

4. Has your child had any of these symptoms in the past

4 weeks: high temperature, rash, cough, cold, sore

throat?

5. Has your child been in contact with an infectious disease

in the past 4 weeks?

6. Does your child have any heart problems?

7. Has your child ever been short of breath while exercising

or been blue around the lips?

8. Does your childs chest ever sound wheezy and whistling?

9. Does your child have any kidney problems?

10. Has your child ever been jaundiced?

11. Does your child bruise easily?

12. Has your child ever had any convulsions or seizures?

13. Does your child, or does anyone in the family, have nerve

or muscle problems?

14. Have your child or family members ever had problems

with anaesthesia?

15. Does your child have any other medical conditions?

16. For female children: has your child started her periods?

If yes, what was the date of her last menstrual period?

17. Is there any chance that your child might be pregnant?

Do you smoke, or you have stopped recently?

(if yes, how many a day?)

Do you drink alcohol (if yes, how much a week?)

Do you have false, capped or crowned teeth?

Do you wear contact lenses or a hearing aid?

Do you have a pacemaker or any implants?

Women

Could you be pregnant?

Are you on the pill or HRT?

What is your approximate weight?

What is your approximate height?

Are you taking any medicines or drugs?

Are you allergic to any drugs or materials?

Please list any previous operations or anaesthetics

Have you, or any member of your family, had any problems

with anaesthetics?

Is there anything else that your anaesthetist or surgeon

should know?

In several studies, specific preoperative outcomes (eg,

cardiac, respiratory) have been reported in patients with

specific pre-existing conditions (eg, hypertension, previous

myocardial infarction, smoking, airway abnormalities).1420

However, since these studies were not controlled trials, they

were not judged to be rigorous enough to provide

unequivocal evidence.

Interview

The preoperative interview is the anaesthetists first

introduction to a patient. This is the most efficient and

productive of the three basic techniques used in

preoperative assessment. The objectives of the interview in

patients who are presumed to be basically healthy is to

detect unrecognised disease that could increase the risk of

surgery above the baseline.21 The preoperative medical

history should focus on the indication for surgical

procedures, allergies, and undesirable side-effects to

medications or other agents, known medical problems,

surgical history, major trauma, and current medications. A

focused review of issues pertinent to the planned anaesthetic

procedures (cardiopulmonary function, homoeostatic

status, possibility of pregnancy, personal or family history of

1750

anaesthetic problems, smoking and drinking habits, and

functional status) has also been shown to be useful.22,23

Questionnaires are an effective way of gleaning basic

background information. Many institutions have developed

questionnaires to improve efficiency in preoperative clinics.

They can be given to the patient at the surgical outpatient

clinic to be completed immediately or taken home and

returned by post. However, questionnaires should not be

seen as a substitute for preoperative interview but as an

additional source of information. The questionnaire is not

supposed to shorten the consultation but to reduce the time

spent asking basic questions, allowing more time to discuss

the actual problem and the operation (panels 1 and 2).13, 2325

Physical examination

A complete physical examination in presumed healthy

individuals includes:2,23 weight and height; main vital signs

blood pressure, pulse (rate and regularity), and respiratory

rate; cardiac and pulmonary examination; anatomical

conditions required for specific anaesthetic procedures,

such as intubation (airway examination), regional

anaesthesia, venous access, etc; and other particular

examinations thought to be of use.

Routine tests

Most patients admitted for elective surgery undergo a range

of routine preoperative tests. These tests, whether or not

guided by the patients clinical needs, have been part of

preoperative clinical practice for many years.7,8,26 The

purposes of routine preoperative testing are: the assessment

of a pre-existing health problem, the identification of

unsuspected medical conditions, the prediction of

preoperative or postoperative complications, the

establishment of a baseline reference for later comparisons,

and the screening of patients opportunistically. This

inappropriate use of resources has been widely

documented,7,2651 especially for the routine chest radiograph,

but besides the small probability of finding a relevant

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

ANAESTHESIA II

SBU7

ANDEM9

OSTEBA8

GR10

NCCHTA6

GPAC11

NICE12

Chest radiography

Electrocardiogram

Immigrants from developing

countries without a chest

radiograph during the

previous 12 months

Immigrants from developing

countries who have not

had a chest radiograph

during the previous

12 months

Men older than 5060 years, When the need for

women older than

transfusions is

6070 years

envisioned

Blood count

Haemostasis

Other analyses

Not recommended

Not indicated

If history suggests risk

of haemorrhage; if not

possible to know the

past history; for special

treatments

The cost-effectiveness

of examination

increases with age,

although the age from

which it must be done

is not clear

If anamnesis suggests

coagulation problems,

difficult surgical

homoeostasis, and for

drinkers of more than

500 mL of wine per

day or equivalent

Immigrants from developing Men and women older

Not recommended routinely

If past history suggests

countries who have not had than 60 years

except in children of younger than haemorrhagic disorders;

a chest radiograph during

1 year of age and patients of non- for treatment with oral

the previous 12 months;

white origin, but recommended for anticoagulants

long-term smokers

surgery in which need for

transfusions is expected

Not indicated

Not indicated

Not indicated

If the anamnesis

suggests homoeostasis

disorders

Not indicated

Not indicated

Not indicated

If the anamnesis

suggests homoeostasis

disorders

Not recommended

Men and women younger

Men and women older than

No recommended

than 60 years if asthmatic or 60 years of age undergoing

smoker. Indicated for those

major surgery.

older than 80 years

Blood urea nitrogen or

creatinine and

glycaemia tests for

people older than

40 years

Men older than 4045 years, Minor surgerydo not do

women older than 55 years

routinely except in patients

younger than 1 year, the elderly,

pregnant women, and immigrants

from developing countries, but

recommended for potentially

haemorrhagic surgery

People older than 60 years; Men and women older than

Not recommended routinely

obese individuals with

60 years; those older than

except in newborns, people older

body-mass index greater

40 years without a previous than 60 years, and fertile women,

than 30; smokers of more

ECG

but recommended for potentially

than 20 cigarettes per day

haemorrhagic surgery (more than

500 mL bloodloss)

Creatinine for persons

over 60 years of age

Not indicated

Not indicated

Renal function in

patients older than

40 years undergoing

a major surgery.

Dipstick urine test in

those older than

16 years

SBU=Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care. ANDEM=Agence Nationale pour le Developpment de lEvaluation Medicale (France). OSTEBA=Office

for Health Technology assessment (Spain). GR=Health Council of the Netherlands. NCCHTA=National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology assessment (UK).

GPAC=Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee (USA). NICE=National Institute for Clinical Excellence (UK).

Indications for preoperative tests for elective surgery in otherwise healthy patients, extracted from systematic reviews

abnormality in the absence of any clinical indication,33,5257

abnormal findings have a surprisingly small effect on

subsequent anaesthetic and surgical management.54,58,59

Drawbacks to the extensive use of routine preoperative

testing are: patients discomfort; unnecessary waiting times

for some procedures; unnecessary direct costs and emerging

opportunity costs; potential for unnecessary subsequent

tests related to false-positive abnormal findings.1,28,60

The evidence suggests that 6070% of preoperative

testing52,61,62 is unnecessary, if a proper history and physical

examination are done.63 Most studies in which the number

of preoperative tests was reduced without adversely

affecting the patients health results have been retrospective.

However, data from some prospective studies48,64 have

confirmed this finding.

Which tests should be ordered preoperatively for elective

surgery? This question, focused on patients with no

symptoms other than those relevant to the planned

operation, has been repeatedly tackled by health technology

assessment agencies since 1989,612 by means of systematic

reviews of published work and, in some cases, by expert

panels or consensus conferences. The UK National

Institute of Clinical Excellence has published a comprehensive review of the evidence on routine preoperative

testing.12 The table shows information about the indications

for preoperative tests in asymptomatic patients.

Because selective ordering of tests, according to the

patients needs, is safer and more efficient for the patient

and the health-care system, some researchers have

investigated the reasons for the internationally widespread

custom of ordering preoperative tests.7,8,26,65,66 A common

reason is protection from legal liability. However, additional

testing does not seem to provide legal protection; in most

retrospective studies a change in management has been

reported in fewer than 5% of patients with abnormal test

findings.54,58,59

Research has been done to obtain information about

attitudes and opinions of anaesthetists about the use of

preoperative assessment tests.7,26,6567 The pioneer study of

the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health

Care from 19897 quantified the high degree of inappropriate

use of preoperative tests for elective surgery. It also obtained

information on the reasons or motives behind the observed

deviations from evidence-based practice through a national

survey of anaesthetists. 60% of participants agreed with the

statement there is no scientific evidence to support

widespread use of chest radiography or ECG in

asymptomatic patients. Studies in Spain26,65,66 and Italy67

had similar findings; about 70% of anaesthetists agreed that

legal liability purposes are among the reasons for most

preoperative tests requested in asymptomatic patients, and

80% of participants rejected, or judged to be doubtful, the

statement that published work supports routine

preoperative testing.

Preoperative risk assessment

Nowadays anaesthesia is safer than it used to be. In a review

of over 100 000 procedures under general and spinal

anaesthesia, patient and surgical risk factors were much

more important than anaesthetic factors in prediction of

7-day mortality.68 The anaesthetist must be aware of any

medical problem of his or her patient, in order to provide

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

1751

ANAESTHESIA II

anaesthesia in the best possible conditions to maximise

safety and comfort.69 The American Society of

Anaesthesiologists classification was the first systematic

attempt to stratify the risk for patients undergoing

anaesthesia. This classification refers to mortality, based

on the general clinical impression of the severity of

systemic illnesses. The anaesthetist is principally

responsible for choosing a particular anaesthetic

technique or agent, and the selection should be based on

the type of procedure to be undertaken and on the specific

needs and risks of the patient. 69

General versus regional anaesthesia

The decision whether to apply general or regional

anaesthesia is a matter of great debate. Early data

suggested that mortality did not differ between the two

approaches.69,70 However, these studies often did not

include the postoperative period, and did not take into

account other outcomes such as time to discharge, patient

satisfaction, and time taken by the anaesthetist. Regional

anaesthetic techniques have now been improved, so older

studies may no longer be valid.69 Most studies comparing

epidural and general anaesthesia have not been adequately

designed to detect clinical differences, since the incidence

of events was low and small numbers of patients were

investigated. Nevertheless, these studies can make us

aware of any potential differences and how they affect our

decisions about the type of anaesthesia to apply.7174

Results of a meta-analysis including 141 trials and

9559 patients showed that epidural or spinal anaesthesia

reduced mortality, risk of myocardial infarction,

transfusion requirements, incidence of pneumonia, and

respiratory

depression,

compared

with

general

anaesthesia.75 Epidural anaesthesia also reduces the risk of

venous thromboembolism and the likelihood of a

thrombophilic

state,

compared

with

general

anaesthesia.7680 The precise mechanism for this reduction

of risk is not clear. Epidural anaesthesia decreases

intraoperative loss of blood, presumably because of a

reduction in arterial blood pressure and a redistribution of

bloodflow. Additionally, elimination of the need for

positive pressure ventilation reduces venous backpressure

into the surgical field. Finally, sympathetic blockade

results in increased bloodflow to the legs and feet.

Cardiac risk

The overall risk of postoperative cardiac death or major

cardiac complications is less than 6% in patients older

than 40 years undergoing major non-cardiac

operations.8182 However, the risk is not uniform, but is

increased by old age and pre-existing heart disease. The

best approach is to identify patients at high risk so that

appropriate testing and therapeutic measures can be

undertaken to reduce or eliminate the risk.83 Several

multivariate indices of risk have been developed for

patients with known or suspected cardiac disease. All

seem to be similar in their ability to predict cardiac

problems during the operation.8487

In 2002, the American College of Cardiology and the

American Heart Association jointly updated the practice

guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular assessment for

non-cardiac surgery.88 These guidelines incorporate

clinical predictors and functional status into the

preoperative risk assessment algorithm, and show how this

assessment can best be undertaken without submitting the

patient to unnecessary interventions. They emphasise that

preoperative testing should be restricted to circumstances

in which the results will affect management and outcome.

The estimation of preoperative risk should integrate

1752

Panel 3: Similarities and differences between

guidelines of the American College of

Cardiology/American Heart Association

(ACC/AHA) and the American College of

Physicians (ACP)

Similarities

Emergency surgery cases proceed directly to the operating

room without further risk stratification

Both algorithms incorporate Detsky predictors86*

Patients eventually placed into low, intermediate, or high risk

categories

Differences

ACC/AHA preoperative guideline

Presence or absence of coronary artery disease is the

first risk assessment

Clinical predictors derived from Goldman82 and Detsky86

criteria

Patients with poor functional status require stress testing

ACP preoperative guideline

Destky criteria are the first determinants of risk

stratification

Minor clinical predictors derived from Eagle87 and

Vanzetto20 criteria

ACP felt functional status not proved to be useful risk

predictor

Patients undergoing vascular surgery require stress

testing

Adapted with permission from Karnath.90 *Detsky and colleagues

reported ten variables associated with an increased risk for

perioperative cardiac complications in patients undergoing noncardiac

surgery (age older than 70 years, myocardial infarction after 6 months,

etc). Each risk factor was assigned a point score, and patients are

stratified into three risk categories based on their total score.

clinical determinants of risk: those who have had coronary

revascularisation in the previous 5 years, or a favourable

result of either coronary angiography or cardiac stress test

in the preceding 2 years, may be submitted to surgery

without further cardiac assessment. The American

College of Physicians has also published guidelines for

assessment and management of perioperative risk.89 Both

sets of preoperative guidelines are evidence-based.

Similarities and differences between the guidelines are

outlined in panel 3.

Pulmonary risk

Postoperative lung complications contribute substantially

to overall peroperative morbidity and mortality.

Pulmonary complications occur significantly more often

than cardiac complications and are associated with

significantly longer hospital stays.91,92 One broad definition

of postoperative lung complication includes an

identifiable disease or dysfunction that is clinically

relevant and adversely affects the clinical course.9396 This

classification would include several major problems such

as atelectasis, infection (bronchitis and pneumonia),

prolonged mechanical ventilation, respiratory failure,

exacerbation of underlying chronic lung disease, and

bronchospasm.

Risk factors for pulmonary complications can be

grouped as patient-related or procedure-related.

Patient-related factors

Chronic lung disease is the most important patient-related

risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complicationsit

increases the risk of postoperative complications 26 to

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

ANAESTHESIA II

6 fold.17,88 Patients with asthma that is well controlled and

with a peak flow measurement of greater than 80% of that

predicted can proceed to surgery with an average risk.97

Current cigarette smokers have an increased risk for

postoperative pulmonary complications, even in the

absence of chronic lung disease. Smokers of more than

20 packs per year have a higher incidence of postoperative

pulmonary complications than those smoking fewer

cigarettes (rate of complications varied from 155% to

55%).98 The relative risk of pulmonary complications in

smokers is four times higher than in people who have not

smoked within the past 2 months.91

Changes related to morbid obesity can accentuate and

increase the risk of postoperative pulmonary

complications. However, there is a clear discrepancy

between different reports. Differences may arise, in part,

because many studies do not adequately distinguish

between obesity itself and comorbid conditions. Despite

controversy, a balanced interpretation of the evidence

suggests that obesity is not a risk factor for postoperative

pulmonary complications and should not affect patient

selection for otherwise high-risk procedures.91,99

The risk due to age alone, once corrected for

comorbidities, seems small, although data are

conflicting.100102

Surgery-related factors

The site of surgery is the most important factor in

predicting the overall risk of postoperative pulmonary

complications. The rate of complications is inversely

related to the distance of the surgical incision from the

diaphragm. Thus, the rate is substantially higher for

thoracic and upper abdominal surgery (1959% and

1617%, respectively) than for lower abdominal surgery

(05%).92,95,101,103

Surgical procedures lasting longer than 34 h are

associated with an increased risk of pulmonary

complications.100,101,104,105 General anaesthesia seems to be

associated with a higher risk of clinically important

pulmonary complications than epidural or spinal

anaesthesia. Regional nerve block is associated with

reduced risk, and should be considered, if possible, for

patients at high risk.75,95,105,106

Preoperative fasting policies

Restricted intake of food and oral fluid before general

anaesthesia has for a long time been judged vital, to

reduce the risk of regurgitation of the gastric contents.

However, preoperative fasting can impair nutrition and

hydration. Anaesthetists concerned with the well-being,

hydration, comfort, and safety of their patient try to

establish safe periods of preoperative fasting without

unnecessary starvation.107,108 Several unsystematic reviews

of the literature109114 have suggested that an overly long

fasting period (such as the traditional nothing by mouth

from midnight) might be unnecessary or even

detrimental to the patient. Any re-assessment of our

fasting policy should be welcome. A number of

associations have published new or revised guidelines

dealing with preoperative fasting inpatients undergoing

elective surgery.108111,113,114 The most comprehensive report

was published in 1999 by the American Society of

Anaesthesiologists,115 which recommended that adults

should have no clear fluids for at least 2 h, and should

take their last light meal at least 6 h before having surgery

with general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia, or sedation

or analgesia. The routine use of gastrointestinal stimulants

to decrease the risk of pulmonary aspiration in otherwise

healthy patients was discouraged.

Children have specific preoperative needs.116,117 Infants

need regular feeding in the form of breastmilk, non-human

milk, or infant formula to prevent hunger, thirst,

hypoglycaemia, dehydration, and discomfort. As a group,

the nutritional needs of children are heterogeneous. For

instance, neonates (<1 month) are different from infants

(1 month to 1 year) and, similarly, the needs of the older

child (>1 year) are different from those of younger

children. Guidelines published by the American Society of

Anaesthesiologists recommend a 6 h fast for non-human

milk or infant formulae for neonates and infants, and a less

strict 4 h policy for breastmilk feeding, before procedures

requiring general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia, or

monitored anaesthetic care.

Patients perspective

The anaesthetists preoperative consultation with the

patient is important to enhance trust and confidence. The

patient should know the anaesthetists name and status. If

the anaesthetist is still in training, the patient will want to

know that his or her levels of competence and experience

are appropriate, and that a senior specialist will be at

hand.13 The preoperative anaesthetic clinic is the place and

time to assess the patients fitness for surgery as well as to

discuss the most appropriate anaesthetic technique in the

light of the patients preferences, clinical state, the

operation itself, and the anaesthetists preferences and

special skills.13,118 This is also the time to help the patient

raise any doubts and questions about aspects of anaesthetic

care, and to obtain the patients explicit consent to what is

agreed. Discussion between anaesthetist and patient

should include how the patient will get to the theatre, if

there is a choice; what will be experienced in the recovery

room, or in ICU, if that is planned; what time the

operation is scheduled, with a prompt explanation if the

time slips; whether a blood transfusion is likely to be given;

how postoperative and postdischarge pain will be managed

and what choices there might be. If the patient is to wake

up with an epidural catheter or a patient-controlled

analgesia machine, intravenous line, oxygen mask, etc,

those too must be explained.3,23

Patients prefer to be seen preoperatively by the same

anaesthetist who will later anaesthetise them.118 Most

anaesthetists agree, and this practice is deemed to be a

marker of high-quality anaesthesia by the UK Association

of Anaesthetists.119,120 Finally, a postoperative visit, however

brief, by the anaesthetist, completes the patients

perception of good quality of care.

Legal issues

As far as medical responsibility is concerned, no specific

rules can be formulated, neither for anaesthetists or any

other medical specialists, nor for the different medical

acts. In October, 1987, the US Congress approved the

duties of preanaesthetic care (last modified in October,

1993), stating that the anaesthetist has a responsibility to

determine the medical condition of the patient, to develop

a plan of anaesthetic care, and to inform the patient or

guardian of this plan. These principles apply to all patients

who are going to undergo anaesthesia or a monitored

anaesthetic procedure121 and can only be modified in

special circumstances, such as an extreme emergency. The

specifications state that preoperative screening tests are

usually useful, but no systematic tests are required for

the pre-anaesthetic assessment.121 Anaesthetists, the

anaesthetic department, and medical institutions should

develop scientifically based guidelines to define the tests to

be used preoperatively. The probable contribution of each

test to the final result of surgery should be assessed

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

1753

ANAESTHESIA II

individually. Every anaesthetist should, additionally, ask

for any specific tests, the results of which could affect, in

his or her opinion, the decisions to take, the risks involved,

and the ways to control the anaesthesia and surgery in

every individual case.

In France, a 1974 government circular established the

preoperative anaesthetic consultation as compulsory; the

assessment must be summarised in a preoperative report,

and done far enough in advance to allow time for all the

necessary complementary tests.122

In other countries, there are no similarly defined

regulations. In Spain, failure to do adequate preoperative

tests is judged, in view of recent court cases, to be serious

negligence, unless surgery is urgent and vital. Biochemical

and haematological tests, radiography, and an electrocardiogram have been judged, in legal cases, to be

necessary to show the true condition of the patient and to

eliminate, or at least diminish, the likelihood of treatment

failure or death.123 However, as previously mentioned,

there is much evidence that routine preoperative testing is

done, not for clinical reasons, but to prevent possible legal

claims by the patients.5

Cost of routine preoperative assessment

The broad use of routine preoperative tests generates costs

in several ways: the cost of the tests, the cost of follow-up

tests to ascertain the importance of any abnormal findings,

the need for additional consultations, and delays in

surgery.1 The costs are not negligible, and can be

substantially reduced through appropriate selective

ordering of preoperative diagnostic tests. Economic

analyses on preoperative assessment have been undertaken

in Sweden, Spain, the UK, and the USA,7,8,49,124,125 reaching

estimates of savings that could be achieved if evidencebased protocols were implemented. In Sweden the annual

costs generated by preoperative investigations were

estimated to be 726 million Swedish crowns (SEK),

including one inpatient day in 75% of all patients

undergoing surgery. With restricted criteria for

preoperative investigations, the potential savings in the

long term were calculated as SEK 100200 million per

year in 1989 (or roughly $167 000$334 000).7 In Spain

(Basque Country, 1992), the potential estimated reduction

in yearly costs of preoperative testing, according to

different uses of a scientific based protocol8 for healthy

patients needing elective surgery, was US$286 million in

1998.126 The same procedure, applied to healthy patients

undergoing elective surgery in the regional public health

system of the Canary Islands, Spain, estimated a potential

cost reduction of 213324 million in 2000 (equivalent

to $226344 million).124 Investigators from a local study

in the UK estimated conservatively that 50 000 ($83 000)

could be saved per year;49 extrapolation to all hospitals in

the National Health Service could result in savings of

several million pounds. In the USA, it has been estimated

that by ordering no laboratory tests except those indicated

by the history or physical examination, almost $100 could

be saved per patient. Since 29 million patients undergo

some form of surgical procedure annually in USA, about

$29 billion dollars could be saved in total.125 Evidence

suggests that the number of preoperative tests in hospitals

could be reduced without affecting patients outcomes,

and with substantial concomitant reduction in costs.

involvement in making decisions. Information technologies

are powerful instruments for bringing information to

patients and citizens. However, these issues also raise

questions: who is going to lead the processclinicians,

public or patients, health-care administrators, or other

institutions? Who will facilitate the cost-effective selection

of preoperative tests?

Second, there is a strong need for improvement and

increase in research and audit about preoperative

assessment. As NICE pointed out in their recent

publication,12 there is no empirical evidence for the benefits

of preoperative testing in the healthy or asymptomatic

population, since there are few comparative studies on

alternative strategies for testing. Meanwhile, the costs and

results of alternative strategies for preoperative testing

could be monitored in different groups of patients. If

safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness are going to be

the leading principles in decision-making in preoperative

testing, research is needed to identify the best test strategy

and the best methods in every surgical condition. The poor

quality of study design, execution, and reporting also limit

the validity and usefulness of the available noncomparative studies. We propose that future research

projects should include a prospective case-series

investigating the effect on clinical management of routine

testing in patients older than 60 years, and a randomised

trial of outcomes and costs, etc, in patients who do or do

not have the full set of routine preoperative tests. Further

analysis of the existing evidence could include: estimates of

the predictive values or likelihood ratios for different tests

in respect of postoperative events, from studies that

contain adequate data; meta-analysis of pooled results

from existing studies and economic modelling of the

probable resource costs and patients outcomes in current

practice, by use of best estimates of test performance.

Professional societies should take the initiative to

implement and assess a continuing education system that

would effectively bring updated scientific information to

clinicians, allowing them to improve their knowledge and

use the results of research. However, the complexity of

medical decision-making on this topic means that we need

more than better research, education, training, and

scientific based guidelines. How do we address the issues

of fear and the practice of defensive medicine, and the

need for a comprehensive strategy to bring together

scientific societies, health-care administrators, public

representatives, and judicial organisations?

We thank Diego Reverte and Eduardo Tello for their valuable assistance

in the preparation of this manuscript

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

1

2

3

4

5

The future

First, the public and patients are willing to play a more

active role in the decision-making process on their own

health.127129 Some health-care systems are working to

empower citizens and patients to improve the value of their

1754

Roizen MF. More preoperative assessment by physicians and less

by laboratory tests. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 20405.

American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia

Evaluation. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: a report

by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on

Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2002; 96: 48596.

Myers LM. Preoperative evaluation. Florida: Jacksonville Medicine,

1998.

Lundberg D, Hgerdal M. Pre-anaesthetic assessment.

Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40: 961.

Roizen MF. What is necessary for preoperative patient assessment?

In: Barash PG, Deutsch S, Tinker J, eds. The American Society

of Anesthesiologists. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1995:

189202.

Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J. Routine preoperative testing: a

systematic review of the evidence. Southampton: National

Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment, 1997.

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

ANAESTHESIA II

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care

(SBU). Preoperative routines. Stockholm: SBU, 1989.

Office for Health Technology Assessment (OSTEBA).

Healthy/asymptomatic patient preoperative evaluation. VictoriaGasteiz: Health Department, 1994.

Agence Nationale pour le Development de lEvaluation Medicale

(ANDEM). Indication of Preoperative Tests. Paris: ANDEM, 1992.

Health Council of the Netherlands, Gezondheidsraad (GR).

Preoperative Evaluation. Den Haag: Gezondheidsraad, 1997.

Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee (GPAC), Medical

Services Commission, and British Columbia Medical Association.

Guideline for Routine Pre-Operative Testing. Victoria BC: Ministry

of Health, 2000.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2003) Guidance on the use

of preoperative tests for elective surgery. NICE Clinical Guideline

No 3. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2003.

The association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.

Pre-operative assessment. The role of the anaesthetist.

http://www.aagbi.org/pdf/pre-operative_ass.pdf (accessed Nov 10,

2003)

Duncan PG, Cohen MM. Postoperative complications: factors of

significance to anaesthetic practice. Can J Anaesth 1987; 34: 28.

Eagle KA, Brundage BH, Chaitman BR, et al. Guidelines for

perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery: report

of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association

Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Perioperative

Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery). J Am Coll Cardiol

1996; 27: 91048.

Forrest JB, Rehder K, Cahalan MK, Goldsmith CH. Multicenter

study of general anesthesia. III. Predictors of severe perioperative

adverse outcomes. Anesthesiology 1992; 76: 315.

Kroenke K, Lawrence VA, Theroux JF, Tuley MR, Hilsenbeck S.

Postoperative complications after thoracic and major abdominal

surgery in patients with and without obstructive lung disease. Chest

1993; 104: 144551.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Evaluation and preparation of

pediatric patients undergoing anesthesia (RE9633). Pediatrics 1996;

98: 50208.

Lawrence VA, Dhanda R, Hilsenbeck SG, Page CP. Risk of

pulmonary complications after elective abdominal surgery. Chest

1996; 110: 74450.

Vanzetto G, Machecourt J, Blendea D, et al. Additive value of

thallium single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial

imaging for prediction of perioperative events in clinically selected

high cardiac risk patients having abdominal aortic surgery.

Am J Cardiol 1996; 77: 14348.

Smetana GW. Preoperative medical evaluation of the healthy patient

(Up To Date Review). Up To Date 2002; 10: N3.

http://www.uptodate.com (accessed Jan 30, 2003).

Arvidsson S, Ouchterlony J, Nilsson S, Sjstedt L, Svrdsudd K. The

Gothenburg study of preoperatory risk. I. Preoperative findings,

postoperative complications. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1994; 38:

67990.

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Health Care Guideline:

Preoperative evaluation. Bloomington: Institute for Clinical Systems

Improvement, 2002.

Alcalde J, Ruiz P, Acosta F, Landa JI, Jaurrieta E. Proyecto para la

elaboracin de un protocolo de evaluacin preoperatoria en ciruga

programada. Cir Esp 2001; 69: 58490.

Ladfors MB, Lofgren MEO, Gabriel B, Olsson JHA. Patient accept

questionnaires integrated in clinical routinea study by the Swedish

National Register of Gynecological Surgery. December 2001.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002; 81: 43742.

Serrano Aguilar P, Lpez Bastida J, Duque Gonzlez B, et al.

Preoperative testing routines for healthy, asymptomatic patients in the

Canary Islands (Spain). Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2001; 48: 30713.

Kerr IH. Preoperative chest x ray. Br J Anaesth 1974; 46: 55863.

Sagel SS, Evens RG, Forrest JV. Efficacy of routine screening and

lateral chest radiographs in a hospital based population. N Engl J Med

1974: 291; 100104.

Seymour DC, Pringle R, Shaw JW. The role of the routine preoperative chest x-ray in the elderly general surgical patient.

Postgrad Med J 1982; 58: 74145.

Rees AM, Roberts CJ, Bligh AS, Evans KT. Routine preoperative

chest radiography in non-cardiopulmonary surgery. BMJ 1976; 1:

133335.

Sane SM, Worsing RA Jr, Wiens CW, Sharma RK. Value of

preoperative chest X-ray examinations in children. Pediatrics 1977; 60:

66972.

Umbach GE, Zubek S, Deck HJ, Buhl R, Bender HG, Jungblut RM.

The value of preoperative chest X-rays in gynecological patients.

Arch Gynecol Obstet 1988; 243: 17985.

33 Adams JG Jr, Weigelt JA, Poulos E. Usefulness of preoperative

laboratory assessment of patients undergoing elective herniorrhaphy.

Arch Surg 1992; 127: 80104.

34 MacDonald JB, Dutton MJ, Stott DJ, Hamblen DL. Evaluation of

pre-admission screening of elderly patients accepted for major joint

replacement. Health Bull Edinb 1992; 50: 5460.

35 Ramsey G, Arvan DA, Stewart S, Blumberg N. Do preoperative

laboratory tests predict blood transfusion needs in cardiac operations?

J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983; 85: 56469.

36 Jones MW, Harvey IA, Owen R. Do children need routine

preoperative blood-tests and blood cross matching in orthopedic

practice. Ann R C Surg Engl 1989; 71: 13.

37 Kozak EA, Brath LK. Do screening coagulation tests predict bleeding

in patients undergoing fiberoptic bronchoscopy with biopsy? Chest

1994; 106: 70305.

38 Manning SC, Beste D, McBride T, Goldberg A. An assessment of

preoperative coagulation screening for tonsillectomy and

adenoidectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1987; 13: 23744.

39 Aghajanian A, Grimes DA. Routine prothrombin time determination

before elective gynecologic operations. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 78:

83739.

40 Bouillot JL, Fingerhut A, Paquet JC, Hay JM, Coggia M. Are routine

preoperative chest radiographs useful in general surgery? A

prospective, multicentre study in 3959 patients. Association des

Chirurgiens de lAssistance Publique pour les Evaluations medicales.

Eur J Surg 1996; 162: 597604.

41 Lavernia CJ, Hernandez RA, Rodriguez JA. Perioperative X-rays in

arthroplasty surgery: outcome and cost. J Arthroplasty 1999; 14:

66971.

42 Garca-Miguel FJ, Garca Caballero J, Gmez de Caso-Canto JA.

Indications for thoracic radiography in the preoperative evaluation for

elective surgery. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2002; 49: 8088.

43 Garca-Miguel FJ, Garca Caballero J, Gmez de Caso-Canto JA.

Indications for electrocardiogram in the preoperative assessment for

programmed surgery. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2002; 49: 512.

44 Escolano F, Gomar C, Alonso J, Sierra P, Cabrera JC, Castao J.

Usefulness of the preoperative electrocardiogram in elective surgery.

Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 1996; 43: 30509.

45 Silvestri L, Maffessanti M, Gregori D, Berlot G, Gullo A. Usefulness

of routine pre-operative chest radiography for anaesthetic

management: a prospective multicentre pilot study. Eur J Anaesthesiol

1999; 16: 74960.

46 Murdoch CJ, Murdoch DR, McIntyre P, Hosie H, Clark C. The preoperative ECG in day surgery: a habit? Anaesthesia 1999; 54: 90708.

47 Liu LL, Dzankic S, Leung JM. Preoperative electrocardiogram

abnormalities do not predict postoperative cardiac complications in

geriatric surgical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 118691.

48 Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, et al. The value of routine preoperative

medical testing before cataract surgery. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:

16875.

49 Johnson RK, Mortimer AJ. Routine pre-operative blood testing: is it

necessary? Anaesthesia 2002; 57: 91417.

50 Alsumait BM, Alhumood SA, Ivanova T, Mores M, Edeia M. A

prospective evaluation of preoperative screening laboratory tests in

general surgery patients. Med Princ Pract 2002; 11: 4245.

51 Ansermino JM, Than M, Swallow PD. Pre-operative blood tests in

children undergoing plastic surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1999; 81:

17578.

52 Kaplan EB, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ. The usefulness of

preoperative laboratory screening. JAMA 1985; 253: 357681.

53 Narr BJ, Hansen TR, Warner MA. Preoperative laboratory screening

in healthy Mayo patients: cost effective elimination of tests and

unchanged outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc 1991; 66: 15559.

54 Tape TG, Mushlin AI. How useful are routine chest x-rays of 55

preoperative patients at risk for postoperative chest disease?

J Gen Intern Med 1988; 3: 1520.

55 Rucker L, Frye EB, Staten MA. Usefulness of screening chest

roentgenograms in preoperative patients. JAMA 1983; 250: 320911.

56 Mendelson DS, Khilnani N, Wagner LD, Rabinowitz JG.

Preoperative chest radiography: value as a baseline examination for

comparison. Radiology 1987; 165: 34143.

57 Gagner M, Chiasson A. Preoperative chest X-ray films in elective

surgery: a valid screening tool. Can J Surg 1990; 33: 27174.

58 Turnbull JM, Buck C. The value of preoperative screening

investigations in otherwise healthy individuals. Arch Intern Med 1987;

147: 110105.

59 Johnson H Jr, Knee-Ioli S, Butler TA, Muoz E, Wise L. Are routine

preoperative laboratory screening tests necessary to evaluate

ambulatory surgical patients? Surgery 1988; 104: 63945.

60 Loder RE. Routine preoperative chest radiography. 1977 compared

with 1955 at Peterborough District General Hospital. Anaesthesia

1978; 33: 97274.

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

1755

ANAESTHESIA II

61 Macario A, Roizen MF, Thisted RA, Kim S, Orkin FK, Phelps C.

Reassessment of preoperative laboratory testing has changed the

test ordering pattern of physicians. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1992; 75:

53947.

62 Velanovich V. The value of routine preoperative laboratory testing in

predicting postoperative complications: a multivariate analysis.

Surgery 1991; 109: 23643.

63 Roizen MF, Foss JF, Fischer SP. Preoperative evaluation. In:

Miller RD, ed. Anesthesia. 5th edn. Philadelphia: Churchill

Livingstone, 2000: 82483.

64 Narr BJ, Warner ME, Schroeder DR, Warner MA. Outcomes of

patients with no laboratory assessment before anaesthesia and a

surgical procedure. Mayo Clin Proc 1997; 72: 50509.

65 Vilarasau J, Farr M, Martn-Baranera, Oliva G. Survey of

preoperative assessment practices in Catalonia (I). What protocols are

being followed? Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2001; 48: 410.

66 Oliva G, Vilarasau Farr J, Martn-Baranera M. Survey of

preoperative assessment practices in Catalonia (II). How do the

anesthesiologists and surgeons involved view current practice?

Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2001; 48: 1116.

67 Ricciardi G, Angelillo IF, Del Prete U, et al. Routine preoperative

investigation. Results of a multicenter survey in Italy.

Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1998; 14: 52634.

68 Cohen MM, Duncan PG, Tate RB. Does anesthesia contribute to

perioperative mortality? JAMA 1988; 260: 285963.

69 Kaboli PJ, Wilson S, Steven Hata J. Anesthesia techniques and their

impact on perioperative management (Up To Date Review). Up

To Date 2002; 10: N3. http://www.uptodate.com (accessed Jan 30,

2003).

70 Davis FM, Woolner DF, Frampton C, et al. Prospective multicentre trial of mortality following general or spinal anaesthesia

for hip fracture surgery in the elderly. Br J Anaesth 1987; 59:

108088.

71 Tuman KJ, McCarthy RJ, March RJ, De Laria GA, Patel RV,

Ivanovich AD. Effects of epidural anesthesia and analgesia on

coagulation and outcome after major vascular surgery. Anesth Analg

1991; 73: 696704.

72 Christopherson R, Beatti C, Frank SM, Norris EJ, Meinert CL,

Gottlieb SO. Perioperative morbidity in patients randomized to

epidural or general anesthesia for lower extremity vascular surgery.

The Perioperative Ischemia Randomized Anesthesia Trial Study

Group. Anesthesiology 1993; 79: 42234.

73 Bode RH Jr, Lewis KP, Zarich SW, et al. Cardiac outcome after

peripheral vascular surgery. Comparison of general and regional

anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1996; 84: 313.

74 Baron JB, Bertrand M, Barr E, et al. Combined epidural and general

anesthesia versus general anesthesia for abdominal aortic surgery.

Anesthesiology 1991; 75: 61118.

75 Rodgers A, Walker N, Schug S, et al. Reduction of postoperative

mortality and morbidity with epidural or spinal anaesthesia:

results from overview of randomised trials. BMJ 2000; 321:

149396.

76 Modig J, Borg T, Karlstrom G, Maripuu E, Sahlstedt B.

Thromboembolism after total hip replacement: role of epidural and

general anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1983; 62: 17480.

77 Mitchell D, Friedman RJ, Baker JD 3rd, Cooke JE, Darcy MD,

Miller MC 3rd. Prevention of thromboembolic disease following total

knee arthroplasty. Epidural versus general anesthesia. Clin Orthop

1991; 269: 10912.

78 Nielsen PT, Jorgensen LN, Albrecht-Beste E, Leffers AM,

Rasmussen LS. Lower thrombosis risk with epidural blockade in knee

arthoplasty. Acta Orthop Scand 1990; 61: 2931.

79 Sorenson RM, Pace NL. Anesthetic techniques during surgical repair

of femoral neck fractures. A metaanalysis. Anesthesiology 1992; 77:

1095104.

80 Prins MH, Hirsh J. A comparison of general anesthesia and regional

anesthesia as a risk factor for deep vein thrombosis following hip

surgery: a critical review. Thromb Haemost 1990; 64: 497500.

81 Joffe II, Morgan JP. Estimation of coronary risk before noncardiac

surgery (Up To Date Review). Up To Date 2002; 10: N3.

http://www.uptodate.com (accessed Jan 30, 2003).

82 Goldman L, Caldera DL, Nussbaum SR, et al. Multifactorial index of

cardiac risk in noncardiac surgical procedures. N Engl J Med 1977;

297: 84550.

83 Shammash JB, Mohler ER, Kimmel SE. Management of high-risk

patients with vascular disease prior to major noncardiac surgery (Up

To Date Review). Up To Date 2002; 10: N3.

http://www.uptodate.com (accessed Jan 30, 2003).

84 Gilbert K, Larocque BJ, Patrick LT. Prospective evaluation of cardiac

risk indices for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Ann Intern Med 2000; 133: 35659.

85 Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and

1756

prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk

of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100: 104349.

86 Younis LT, Miller DD, Chaitman BR. Preoperative strategies to

assess cardiac risk before noncardiac surgery. Clin Cardiol 1995; 18:

44754.

87 Eagle KA, Coley CM, Newell JB, et al. Combining clinical and

thallium data optimizes preoperative assessment of cardiac risk before

major vascular surgery. Ann Intern Med 1989; 110: 85966.

88 Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al. ACC/AHA guideline update

for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery:

executive summary: a report of the American College of

Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice

Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1996 Guidelines on

Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery).

J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 54253.

89 Guidelines for assessing and managing the perioperative risk from

coronary artery disease associated with major noncardiac surgery.

American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127:

30912.

90 Karnath BM. Preoperative cardiac risk assessment. Am Fam Physician

2002; 66: 188996.

91 Smetana GW. Evaluation of preoperative pulmonary risk. (Up To

Date Review). Up To Date 2002; 10: N3. http://www.uptodate.com

(accessed Jan 30, 2003).

92 Mohr DN, Jett JR. Preoperative evaluation of pulmonary risk factors.

J Gen Intern Med 1988; 3: 27787.

93 ODonohue WJ. Postoperative pulmonary complications: When are

preventive and therapeutic measures necessary? Postgrad Med 1992;

91: 16770.

94 Hall JC, Tarala MD, Hall JL, Mander J. A multivariate analysis of the

risk of pulmonary complications after laparotomy. Chest 1991; 99:

92327.

95 Gracey DR, Divertie MB, Didier EP. Preoperative pulmonary

preparation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; a

prospective study. Chest 1979; 76: 12329.

96 Smetana GW. Preoperative pulmonary evaluation. N Engl J Med

1999; 340: 93744.

97 Warner DO, Warner MA, Barnes RD, et al. Perioperative respiratory

complications in patients with asthma. Anesthesiology 1996; 85:

46067.

98 Warner MA, Offord KP, Warner ME, Lennon RL, Conover MA,

Jansson-Schumacher V. Role of preoperative cessation of smoking

and other factors in postoperative pulmonary complications: a blinded

prospective study of coronary artery bypass patients. Mayo Clin Proc

1989; 64: 60916.

99 Pasulka PS, Bistian BR, Benotti PN, Blackburn GL. The risks of

surgery in obese patients. Ann Intern Med 1986; 104: 54046.

100 Kroenke K, Lawrence VA, Theroux JF, Tuley MR. Operative risk in

patients with severe obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med

1992; 152: 96771.

101 Moller AM, Maaloe R, Pedersen T. Postoperative intensive care

admittance: the role of tobacco smoking. Acta Anesthesiol Scand 2001;

45: 34548.

102 Thomas DR, Ritchie CS. Preoperative assessment of older adults.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43: 81121.

103 Arozullah AM, Daley J, Henderson WG, Khuri SF. Multifactorial risk

index for predicting postoperative respiratory failure in men after

major noncardiac surgery. The National Veterans Administration

Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg 2000; 232:

24253.

104 Brooks-Brunn JA. Predictors of postoperative pulmonary

complications following abdominal surgery. Chest 1997; 111:

56471.

105 Celli BR, Rodrguez KS, Snider GL. A controlled trial of intermittent

positive pressure breathing, incentive spirometry, and deep breathing

exercises in preventing pulmonary complications after abdominal

surgery. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984; 130: 1215.

106 Yeager MP, Glass DD, Neff RK, Brinck-Johnsen T. Epidural

anesthesia and analgesia in high-risk surgical patients. Anesthesiology

1987; 66: 72936.

107 Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P. Preoperative fasting for adults (protocol

for a Cochrane review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2001.

Oxford: Update Software.

108 Lpez-Muoz AC, Toms Braulio J, Montero R. Guidelines for

preoperative fasting and premedication to reduce the risk of

pulmonary aspiration. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2002; 49:

31423.

109 Kallar SK, Everett LL. Potential risks and preventive measures for

pulmonary aspiration: new concepts in preoperative fasting guidelines.

Anesth Analg 1993; 77: 17182.

110 Petring OU, Blade DW. Gastric emptying in adults: an overview

related to anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care 1993; 21: 77481.

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

ANAESTHESIA II

111 Dowling JL Jr. Nulla per os after midnight reassessed.

Rhode Island Medicine 1995; 78: 33941.

112 Corbett AR, Mortimer AJ. Pre-operative fasting: how long is

necessary? Eur J Anaesth 1997; 14: 55557.

113Pandit UA, Pandit SK. Fasting before and after ambulatory surgery.

J Perianesth Nursing 1997; 12: 18187.

114 Eriksson LI, Sandin R. Fasting guidelines in different countries.

Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40: 97174.

115American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative

Fasting. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of

pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration:

application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures.

Anesthesiology 1999; 90: 896905.

116 Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P. Preoperative fasting for children (protocol

for a Cochrane review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2001.

Oxford: Update Software.

117 Splinter WM, Schreiner MS. Preoperating fasting in children.

Anesth Analg 1999; 89: 8089.

118 Simini B, Bertolini G. Should same anaesthetist do preoperative

anaesthetic visit and give subsequent anaesthetic? Questionnaire survey

of anaesthetists. BMJ 2003; 327: 7980.

119 Simini B. Pre-operative visits by anaesthetists. Anaesthesia 2001; 56:

591.

120 Royal College of Anaesthetists and Association of Anaesthetists of

Great Britain and Ireland. Good practice: a guide for departments of

anaesthesia. 1998.

121 American Society of Anesthesiologists: The ASA Directory of

Members 1994. American Society of Anesthesiologists, Park Ridge,

IL, 1994.

122 Acapem J, Bouillot JL, Paquet JC, Hay JM, Coggia M. La

radiographie thoracique propratoire systmatique en chirurgie

gnrale est-elle utile? Ann Fr Anesth Ranim 1992; 11: 8895.

123 Garca-Miguel FJ. Efectividad del electrocardiograma y la radiografa

de trax preoperatorios en el Hospital General de Segovia. Propuestas

de mejora. PhD thesis, Universidad autnoma de Madrid, 2000:

26971.

124 Lpez-Bastida J, Serrano-Aguilar P, Duque-Gonzlez B,

Talavera-Dniz A. Cost analysis and potential cost savings related to

the use of preoperative tests in hospitals of the Canary Islands (Spain).

Gac Sanit 2003; 17: 13136.

125 Roizen MF. A prospective evalution of the value of preoperative

laboratory testing for office anesthesia and sedation.

J Oral Maxilofac Surg 1999; 57: 2122.

126 Asua J, Lpez-Argumedo M. Preoperative evaluation in elective

surgery. INAHTA Synthesis Report. Int J Technol Assess Health Care

2000; 16: 67383.

127 Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play

in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med 1996; 156: 141420.

128 Jadad A, Rizo C, Enkin M. I am a good patient, believe it or not. BMJ

2003; 326: 129395.

129 Moumjid N, Bremond A, Carrere MO. From information to shared

decision making in medicine. Health Expect 2003; 6: 18788.

THE LANCET Vol 362 November 22, 2003 www.thelancet.com

For personal use. Only reproduce with permission from The Lancet publishing Group.

1757

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Clinical ReasoningDokument4 SeitenClinical Reasoningapi-351971578Noch keine Bewertungen

- Three-Stage Assessment. 2021Dokument14 SeitenThree-Stage Assessment. 2021Mwanja Moses100% (1)

- What Is A PICO QuestionDokument3 SeitenWhat Is A PICO QuestionBoid Gerodias100% (2)

- Football Emergency Medicine Manual 2 EditionDokument152 SeitenFootball Emergency Medicine Manual 2 EditionNicolás Alvarez VidelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical DX in PMR Case by CaseDokument143 SeitenClinical DX in PMR Case by CaseNayem comNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR - Muhammad Aasam Maan: Consultant Pain SpecialistDokument23 SeitenDR - Muhammad Aasam Maan: Consultant Pain SpecialistMuhammad Aasim MaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abdominal Examination: Male - Palpate Prostate Gland Female - Feel For CervixDokument5 SeitenAbdominal Examination: Male - Palpate Prostate Gland Female - Feel For CervixRemelou Garchitorena AlfelorNoch keine Bewertungen

- OBGYN HistoryDokument1 SeiteOBGYN Historysgod34Noch keine Bewertungen

- Case 5 - Pancreatitis-1Dokument4 SeitenCase 5 - Pancreatitis-1ngNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Causes Urinary Retention?Dokument4 SeitenWhat Causes Urinary Retention?darkz_andreaslimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fellowship in Critical Care MedicineDokument12 SeitenFellowship in Critical Care MedicinerajiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MS Obst & GynaeDokument77 SeitenMS Obst & GynaeAmna MunawarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospital Discharge Education For CHFDokument18 SeitenHospital Discharge Education For CHFarafathusein29Noch keine Bewertungen

- Polyhydramnios and Oligohydramnios Clinical ExamDokument2 SeitenPolyhydramnios and Oligohydramnios Clinical ExamAhmad FahroziNoch keine Bewertungen

- OSCE Station 1 Diabetic LL ExamDokument5 SeitenOSCE Station 1 Diabetic LL ExamJeremy YangNoch keine Bewertungen

- psc006 PDFDokument2 Seitenpsc006 PDFPHitphitt Jeleck SangaattNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Guidelines On Management of Dengue Fever & Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever in Children and Adolescents - Sri LankaDokument53 SeitenNational Guidelines On Management of Dengue Fever & Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever in Children and Adolescents - Sri LankaNational Dengue Control Unit,Sri Lanka100% (1)

- Health AssessmentDokument25 SeitenHealth AssessmentGovindaraju Subramani100% (1)

- Critical Thinking and Nursing ProcessDokument49 SeitenCritical Thinking and Nursing ProcessjeorjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preceptor Evaluation of StudentDokument2 SeitenPreceptor Evaluation of Studentapi-382409594100% (2)

- Geriatrics Study GuideDokument44 SeitenGeriatrics Study GuideahkrabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antenatal Care Services: by DR - Chinedu Ibeh Thursday, 16 APRIL 2015Dokument81 SeitenAntenatal Care Services: by DR - Chinedu Ibeh Thursday, 16 APRIL 2015SehaRizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Marketing Plan FinalDokument14 SeitenPractice Marketing Plan Finalapi-317365152Noch keine Bewertungen

- Testicular CancerDokument48 SeitenTesticular Cancerluckyswiss7776848Noch keine Bewertungen

- Osteoid OsteomaDokument24 SeitenOsteoid Osteomadrqazi777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Knee ExaminationDokument14 SeitenKnee ExaminationAsimNoch keine Bewertungen

- A KhamDokument324 SeitenA KhamQuang NhânNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final 2010 GYN Module Clinical ObjectivesDokument36 SeitenFinal 2010 GYN Module Clinical Objectiveslolapell100% (1)

- Nursing Handover of Vital Signs at The Transition of Care Fromthe Emergency Department To The Inpatient Ward Anintegrative ReviewDokument12 SeitenNursing Handover of Vital Signs at The Transition of Care Fromthe Emergency Department To The Inpatient Ward Anintegrative ReviewLilac SpaceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spinal Cord Injury: Andi IhwanDokument31 SeitenSpinal Cord Injury: Andi IhwanAndi Muliana SultaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Proforma Apr-15Dokument11 SeitenComprehensive Geriatric Assessment Proforma Apr-15Udin Nicotinic100% (2)

- Orthopediatric LWWDokument398 SeitenOrthopediatric LWWかちえ ちょうNoch keine Bewertungen

- History TakingDokument55 SeitenHistory TakingDeepika MahajanNoch keine Bewertungen

- COPD Follow UpDokument1 SeiteCOPD Follow Upe-MedTools100% (4)

- Olivia Engle NP ResumeDokument1 SeiteOlivia Engle NP Resumeapi-654403621Noch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust PDFDokument291 SeitenClinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust PDFpierdevaloisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pain PhysiologyDokument40 SeitenPain PhysiologyAnmol Jain100% (1)

- Nursing Reflection - 1st Year PostingDokument5 SeitenNursing Reflection - 1st Year PostingNurul NatrahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Please Read The Entire Form Carefully Before SigningDokument2 SeitenPlease Read The Entire Form Carefully Before SigningKoh LudzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Screening ChecklistDokument1 SeiteHealth Screening ChecklistRominaPulvermüllerSalvatierraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Care of The Patient in The Perioperative PeriodDokument20 SeitenCare of The Patient in The Perioperative PeriodMohammed FaragNoch keine Bewertungen

- Template Soap NeuroDokument2 SeitenTemplate Soap NeuroJohan SitepuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Vacuum Assisted Closure TherapyDokument14 SeitenManagement of Vacuum Assisted Closure TherapyVoiculescu MihaelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ThrombophlebitisDokument3 SeitenThrombophlebitismirrejNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case ReportDokument6 SeitenCase ReportJellie MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatric Orthopedic Conditions ManagementDokument142 SeitenPediatric Orthopedic Conditions Managementluh martaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fetal assessment overview under 40 charsDokument3 SeitenFetal assessment overview under 40 charsAde Yonata100% (1)

- Report On Family Planning (4400)Dokument27 SeitenReport On Family Planning (4400)Bikram KushaalNoch keine Bewertungen

- StrokeDokument6 SeitenStrokeRaulLopezJaimeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DDH Treatment - PFDokument30 SeitenDDH Treatment - PFHendra SantosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Incident AnalysisStacy CentenoDokument2 SeitenCritical Incident AnalysisStacy Centenocentenochicago100% (1)

- Cancer Pain ManagementDokument22 SeitenCancer Pain ManagementWanie KafleeNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMP Handy Chart October 2011 V2Dokument69 SeitenMMP Handy Chart October 2011 V2Icha IchaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physical Examination Form: Medications AllergiesDokument4 SeitenPhysical Examination Form: Medications AllergiesIris Ann PhillipsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pa Tool MihpDokument23 SeitenPa Tool MihpNassif M. BangcolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete Physical Examination ChecklistDokument5 SeitenComplete Physical Examination Checklistapi-641836481Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tuberculosis of SpineDokument11 SeitenTuberculosis of SpineSepti RahadianNoch keine Bewertungen

- OSCE Assessment Workshop GuideDokument55 SeitenOSCE Assessment Workshop GuideShouja ChauduryNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICU Scoring Systems A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionVon EverandICU Scoring Systems A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Code Geass - StoriesDokument5 SeitenCode Geass - Stories1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- QLD Rail Traim PDFDokument1 SeiteQLD Rail Traim PDF1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blue Veins Sub Theme TVBDokument4 SeitenBlue Veins Sub Theme TVB1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blue BirdDokument7 SeitenBlue Bird1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mbs Quick Guide: JULY 2020Dokument2 SeitenMbs Quick Guide: JULY 20201234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pokemon Theme Song 22Dokument4 SeitenPokemon Theme Song 221234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fairy Tail - Main ThemeDokument3 SeitenFairy Tail - Main Theme1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topical Steroids (Sep 19) PDFDokument7 SeitenTopical Steroids (Sep 19) PDF1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- USMLE Flashcards: Anatomy - Side by SideDokument190 SeitenUSMLE Flashcards: Anatomy - Side by SideMedSchoolStuff100% (3)

- Osteo Infographic FinalDokument1 SeiteOsteo Infographic Final1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doctor Talk: Communication Practice Role PlaysDokument6 SeitenDoctor Talk: Communication Practice Role Plays1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- # 3 - Prospective Study of The Diagnostic Accuracy of The Simplify D-Dimer Assay For Pulmonary Embolism in EDDokument7 Seiten# 3 - Prospective Study of The Diagnostic Accuracy of The Simplify D-Dimer Assay For Pulmonary Embolism in ED1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

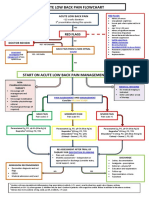

- Acute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 2017Dokument1 SeiteAcute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 20171234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topical Steroids (Sep 19) PDFDokument7 SeitenTopical Steroids (Sep 19) PDF1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Getting the Hospital Job: A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying for Your First PositionDokument41 SeitenGetting the Hospital Job: A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying for Your First Position1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PBM Module1 MTP Template 0Dokument2 SeitenPBM Module1 MTP Template 01234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- VTE GuidelinesDokument11 SeitenVTE Guidelines1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fluids ElectrolytesDokument2 SeitenFluids Electrolytes1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effects of Social Networks On Disability in Older AustraliansDokument22 SeitenThe Effects of Social Networks On Disability in Older Australians1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metro South Intern Training Form (Logan)Dokument3 SeitenMetro South Intern Training Form (Logan)1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 Applicant Guide Web V2Dokument83 Seiten2016 Applicant Guide Web V21234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defining and Assessing Risks To Health PDFDokument20 SeitenDefining and Assessing Risks To Health PDF1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language of PreventionDokument9 SeitenLanguage of Prevention1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- FLOWCHART - ARC Adult Cardiorespiratory ArrestDokument1 SeiteFLOWCHART - ARC Adult Cardiorespiratory Arrest1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taking a Social and Cultural History: A Biopsychosocial ApproachDokument3 SeitenTaking a Social and Cultural History: A Biopsychosocial Approach1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Mental Illness in Patients From CALD Backgrounds: PsychiatryDokument5 SeitenManaging Mental Illness in Patients From CALD Backgrounds: Psychiatry1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Herd Immunity'' A Rough Guide PDFDokument6 SeitenHerd Immunity'' A Rough Guide PDF1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Contributions To Addressing The Social Determinants of HealthDokument5 SeitenClinical Contributions To Addressing The Social Determinants of Health1234chocoNoch keine Bewertungen