Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

11montelongo Summarizing

Hochgeladen von

nonanubatonisOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

11montelongo Summarizing

Hochgeladen von

nonanubatonisCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

Summarizing and Evaluating Text: Process Text Guides

by

Jos A. Montelongo, Ph.D.

California Polytechnic State University

San Luis Obispo, CA 93407

joseamontelongo@yahoo.com

(805) 540-1317

Anita C. Hernndez, Ph.D.

New Mexico State University

Las Cruces, NM 88001

achernan@calpoly.edu

(805) 756-5537

Paper presented at

CATESOL Annual Conference

Santa Clara, California

April 22-25, 2010

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

Summarizing and Evaluating Text: Process Text Guides

Abstract

This paper describes the composition and use of process text guides to teach and

reinforce important expository reading and writing skills. The process text guides

presented here are comprised of a summarization strand and a higher-order thinking

strand. The summarization strand prompts readers to find the main ideas in paragraphs

and use them to create a summary. The higher-order thinking strand uses the same text

with prompts about higher order thinking strategies (e.g., analogies, context clues,

conclusions) embedded throughout the text to simulate the processes of successful

readers.

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

Summarizing and Evaluating Text: Process Text Guides

Many teachers rely on decontextualized workbook activities to teach and

reinforce the various reading and writing skills such as locating the main ideas, drawing

conclusions, understanding analogies, and summarizing text. Since the activities do not

occur as they read authentic text, students do not learn when to deploy the skills the

activities are intended to teach. This has resulted in students who are able to satisfactorily

complete stand-alone drills on worksheets, but who are unable to read, write, and

summarize expository or informational text. Latino English Language Learners, to a

greater extent than other students, require authentic contexts to develop their reading,

writing, and summarization abilities.

Process text guides are teacher-developed resources for helping students

comprehend, summarize, and evaluate particular ideas and concepts arising in text as they

read (McKenna, Davis, and Franks, 2003; Montelongo, 2008; Wood, Lapp, and Flood,

1992). Process text guides prompt student readers with questions about the paragraph(s)

they have just read. The questions are meant to simulate the reading processes

successful readers use as they read informational or expository text. Specifically,

process text guides can be used to support the development of summarization and higherorder thinking skills. The guides are meant to reinforce reading skills such as questioning

the text, finding main ideas, using context clues, drawing conclusions, understanding

cause and effect, and summarizing. Process text guides permit teachers to control the

attention given by students to text content via guiding questions or meaning-making

activities during reading. Process text guides give teachers the power to insert activities

and ancillary materials such as graphic organizers or tables in places where student

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

learning may be most enhanced. The text guides also prompt students to deploy

appropriate reading strategies as they read the text. As a result, students dont have to

wait until they have finished reading to know what was expected of them.

Evidence for the effectiveness of the text guides is exemplified by a study

mentioned by McKenna, Davis, and Franks (2003). In that study, third-grade teachers

developed four text guides based on selections from a science text. Students worked

through the guides at different times in the year. The teachers carefully coached the

students on completing the guides. Following this training, the students were asked to

read a science passage containing information unrelated to any they had studied before.

The group that had been taught using process text guides comprehended more than the

control group that did not have the guides.

In this manuscript, we present a process text guide that includes two strands of

activities, each with its own types of questions and activities. The summarization strand

attempts to develop students summarization skills by prompting the students to locate

the main idea in each paragraph. The higher-order thinking strand is comprised of

activities designed to prompt students to engage in higher-order thinking through

embedded exercises requiring drawing conclusions, making inferences, and questioning

text. Finally, students evaluate the text in terms of what they learned and what they want

to learn more about the topic. A summary of the two strands is presented in Table 1.

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

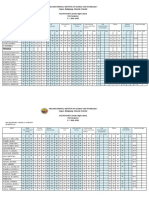

Table 1. Exercises included in summarization and higher-order thinking strands.

Summarization Strand

Higher-Order Thinking Strand

Find the Main Ideas

Draw Conclusions

Note Important Details

Use Context Clues

Categorize Related ideas

Question Text

Paraphrase

Invent Analogies

Summarize

Critique Authors Propositions

Summarization Strand

Reading experts have identified the ability to summarize text as an essential

element of a reading curriculum (Duke and Pearson, 2002). Process text guides are ideal

for helping Latino English Language Learners summarize expository text because they

include structured steps and activities that help students write summaries of the assigned

informational text.

Kintsch and van Dijk (1978) proposed a seminal psychological model of

informational representation that may be generalized to the teaching of summarization.

The steps outlined by Kintsch and van Dijk can be incorporated into the process text

guides for summarizing expository text. First, students read the entire text in order to gain

an overview of the content. Next, they deconstruct each one of the texts paragraphs, one

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

by one, until all of the main ideas have been selected. Then, the students group the related

main ideas. Within each group of related main ideas, the students synthesize a

superordinate main idea from these main ideas, or generate their own if none is explicitly

stated. The remaining main ideas act as the supporting details for the paragraph. Finally,

students re-write the main ideas in their own words as their summary. The ability of the

students to re-write a summary in their own voices can be further used to assess their

comprehension of the text.

The summarization strand of an abridged process text guide is presented in Figure

1. To complete the text guides, students first read the text in its entirety. Since the

comprehension of text necessarily precludes the questioning of text and evaluation,

students complete the summarization strand prior to the higher-order thinking strand. To

complete the summarization strand, the students locate the main idea from every one of

the texts paragraphs. Students then compile all of the main ideas and group the main

ideas according to the various subtopics, finally composing a paragraph for each of the

subtopics. As a result of this process, students create a summary of the informational text.

To complete the summarization strand on states of matter included in Figure 1,

students read each paragraph and choose the main idea. After they have done this for all

of the twelve paragraphs (only 3 paragraphs are shown) in the unit, the students write

down all the main ideas and use these to write a summary. In the process students can

form a mental representation of the text. They discover the relationships among the

various propositions and concepts and form a mental representation of the information.

This mental representation will provide students with a means for recalling the

information and perhaps, as a springboard for generating new ideas.

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

Figure 1. First page of the summarization strand of a fifth-grade textbook.

Changing States of Matter

[1]

Matter may exist as a solid, a liquid, or a gas. Most matter exists in one or more of

these states. Water, for instance, exists in three statessolid, liquid, and gas. It is a solid

piece of ice when frozen, a liquid when it melts, and a gas when it evaporates. Which

state it is in depends on the conditions at the time, such as temperature and pressure.

The main idea of this paragraph is:_______

a.

Most matter exists in one or more of these states: solid, liquid, or gas.

b.

Water, for instance, exists in three statessolid, liquid, and gas.

c.

It is a solid piece of ice when frozen, a liquid when it melts, and a gas when it

evaporates.

[2]

The three states of matter differ with respect to shape and volume. A solid has a

definite shape and a definite volume. A liquid has a definite volume, but no definite

shape. For example, when you pour orange juice, a liquid, from a jug into a glass, the

shape of the juice changes to fit the container. The volume of juice, however, doesnt

change. A gas does not have a definite shape or volume. If you put air into a tire, for

instance, it takes the same shape as the tire. Even when the tire seems full, you can still

put more air into it.

The main idea of this paragraph is:_______

a.

The three states of matter differ with respect to shape and volume.

b.

A solid has a definite shape and a definite volume.

c.

For example, when you pour orange juice, a liquid, from a jug into a glass, the

shape of the juice changes to fit the container.

[3]

You can understand the differences between the states of matter if you think of

matter as particles in motion. In a solid the particles are very close together. Particles are

not packed together as tightly in a liquid. So, they may move more freely than they do in

a solid. The particles in a gas are packed together the least. Since the particles are freer to

move around in gases than solids or liquids, gas particles move the fastest.

The main idea of this paragraph is:_______

a.

The states of matter differ in the movement of their particles.

b.

In a solid the particles are very close together.

c.

Since the particles are freer to move around in gases than solids or liquids, gas

particles move the fastest.

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

Higher-Order Thinking Strand

Once the students have written a summary and formed a mental representation of

the informational text, they can begin to evaluate the entire text by posing and answering

higher-order thinking questions that require going beyond the literal comprehension of

ideas as expressed in a text. In doing so, Latino English Language Learners can acquire

the skills and strategies capable readers use as they read expository text in an authentic

way requiring deeper thinking and application of ideas expressed in a text. Process text

guides serve this purpose. Prompts are strategically embedded in places where successful

readers would use those skills to evaluate as the meaning of a text as it unfolds. This

technique is illustrated by the sample higher-order thinking strand shown in Figure 2.

The sample contains the same paragraphs as those in Figure 1.

In the sample, there are prompts for using context clues, for using a table to

compare and contrast the different states of matter, and a prompt for students to draw the

movement of particles in a solid. Other prompts for creating analogies, drawing

conclusions, questioning the text, etc. could have also been included in a more complete

process text guide. The versatility of process text guides lies in the fact that teachers can

create activities that prompt students to use the strategies successful readers use.

Teachers can also include questions dealing with vocabulary and language for

their Latino English Language learners. Toward this end, they may include questions

about particular vocabulary words or entire sentences in the text. They may also use

context clues activities to assess their students ability to deal with difficult text.

Moreover, teachers are also afforded the opportunity to allow for alternative assessments

such as the drawing of pictures for theirs Latino ELLs and other students.

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

Figure 2. First page of the higher-order thinking strand of a fifth-grade textbook.

Changing States of Matter

[1]

Matter may exist as a solid, a liquid, or a gas. Most matter exists in one or more of

these states. Water, for instance, exists in three statessolid, liquid, and gas. It is a solid

piece of ice when frozen, a liquid when it melts, and a gas when it evaporates. Which

state it is in depends on the conditions at the time, such as temperature and pressure.

[2]

The three states of matter differ with respect to shape and volume. A solid has a

definite shape and a definite volume. A liquid has a definite volume, but no definite

shape. For example, when you pour orange juice, a liquid, from a jug into a glass, the

shape of the juice changes to fit the container. The volume of juice, however, doesnt

change. A gas does not have a definite shape or volume. If you put air into a tire, for

instance, it takes the same shape as the tire. Even when the tire seems full, you can still

put more air into it.

What is the meaning of the word, definite. _________________________________

[3]

You can understand the differences between the states of matter if you think of

matter as particles in motion. In a solid the particles are very close together. Particles are

not packed together as tightly in a liquid. So, they may move more freely than they do in

a solid. The particles in a gas are packed together the least. Since the particles are freer to

move around in gases than solids or liquids, gas particles move the fastest.

Directions: Fill in the table describing three states of matter.

Solid

Shape

Liquid

Gas

definite

Volume

definite

free to move around

Movement of

Particles

[4]

A solid feels firm when it is touched. This is because the particles that make up a

solid are packed up tightly together. They cant be squeezed any closer together because

there is very little space between the particles. This gives a solid a definite volume and

shape. It keeps particles in a solid from moving very much. They are so tightly packed

that each particle stays in the same place and just vibrates.

Draw a picture of particles in a solid.

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

Conclusion

Process text guides help Latino English Language Learners and all learners

acquire reading, writing, and summarizing abilities. By embedding activities in authentic

text, teachers can help students develop into successful readers. Unlike those scenarios

found in classrooms where teachers have students complete stand-alone worksheets,

process text guides provide a scaffold for students to summarize expository texts. Process

text guides also prompt students to emulate the processes successful readers as they

read informational text. With enough practice opportunities to work through process

text[,] guides can build the automaticity successful readers use to become life-long

learners.

Montelongo and Hernndez Process Text Guides

References

Duke, N.K. & Pearson, P.D. (2002). Effective practices for developing reading

comprehension. In A.E. Farstrup and S.J. Samuels (eds.) What research has to say

about reading instruction. Newark, DE: International Reading Association, 205242.

Kintsch, W. and van Dijk, T. (1978). Toward of a model of text comprehension and

production. Psychological Review, 85, 363394.

McKenna, M.C., Davis, L. W., and Franks, S. (2003). Using reading guides with

struggling readers in grades 3 and above. In R. L. McCormack & J. R. Paratore

(eds.) After early intervention, then what? Teaching struggling readers in grades

3 and beyond. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Montelongo, J. A. (2008). Text Guides: Scaffolding Summarization and Fortifying

Reading Skills. International Journal of Learning, 15, 289-296.

Wood, K.D., Lapp, D., & Flood, J. (1992). Guiding readers through text: A review of

study guides. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

10

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Key Concept Sythesis by HellendDokument36 SeitenKey Concept Sythesis by HellenddesiraidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing Creative Thinking to Improve Academic Writing: Part One Intermediate LevelVon EverandDeveloping Creative Thinking to Improve Academic Writing: Part One Intermediate LevelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading-Pre While PostDokument18 SeitenReading-Pre While PostSiti Hajar Zaid100% (1)

- SánchezDana PartsacadtxtDokument4 SeitenSánchezDana PartsacadtxtAmérica FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 31-Chapter Manuscript-769-1-10-20210915Dokument4 Seiten31-Chapter Manuscript-769-1-10-20210915nourane.zarourNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENG555 UnitPlanDokument8 SeitenENG555 UnitPlanjeanninestankoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bringing Text Analysis To The Language Classroom: Presented byDokument77 SeitenBringing Text Analysis To The Language Classroom: Presented byAdil A BouabdalliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing Mini Lesson Samantha SchwabDokument13 SeitenWriting Mini Lesson Samantha Schwabapi-357033410Noch keine Bewertungen

- 9.3 Communicating About Our World Through Informational TextDokument5 Seiten9.3 Communicating About Our World Through Informational TextMarilu Velazquez MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11.3 PersuasionDokument5 Seiten11.3 PersuasionMarilu Velazquez MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elements of The Essay and Writing ProcessDokument23 SeitenElements of The Essay and Writing ProcessNataniel Matías RiveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Essay Writing Skills Using Cooperative Learning Approach: The Case of Princess Alia University CollegeDokument26 SeitenTeaching Essay Writing Skills Using Cooperative Learning Approach: The Case of Princess Alia University CollegeLyyn 7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Summarizing and ParaphrasingDokument40 SeitenSummarizing and ParaphrasingCay MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Bloom's Taxonomy in Teaching Reading SkillDokument8 SeitenUsing Bloom's Taxonomy in Teaching Reading SkillHa To100% (1)

- Ri 3 8 UnitDokument5 SeitenRi 3 8 Unitapi-261915236Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introductions ConclusionsDokument12 SeitenIntroductions ConclusionsAndrea_Magnifi_4983Noch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Strategies For Developing LiteracyDokument26 SeitenBasic Strategies For Developing Literacyq237680Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research 9 Week 1 FinalDokument6 SeitenResearch 9 Week 1 FinalClifford LachicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definitions of ReadingDokument6 SeitenDefinitions of ReadingTiQe 'ansaewa' Sacral HanbieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Informational Text Toolkit: Research-based Strategies for the Common Core StandardsVon EverandInformational Text Toolkit: Research-based Strategies for the Common Core StandardsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Product Vs Process in WritingDokument2 SeitenProduct Vs Process in WritingPaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Synthesis of Research On Teaching WritingDokument6 SeitenSynthesis of Research On Teaching Writingafbsyebpu100% (2)

- Synthesis Research Paper TopicsDokument7 SeitenSynthesis Research Paper Topicsb0sus1hyjaf2100% (2)

- FP006 MA Eng - Trabajo Serrano Costa AraujoDokument10 SeitenFP006 MA Eng - Trabajo Serrano Costa AraujoAntonella Serrano CostaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 6 Ela Unpacked DocumentsDokument35 SeitenGrade 6 Ela Unpacked Documentsapi-254299227Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Creating Writing Strategy and Evaluation Tool For Book SummaryDokument13 SeitenA Study On Creating Writing Strategy and Evaluation Tool For Book SummaryNariye SeydametovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnalysisDokument88 SeitenAnalysisAneesa Younis YounisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of ReadingDokument4 SeitenTheories of Readingmaanyag6685Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Plan 3Dokument4 SeitenAssessment Plan 3api-309656697Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sequential Problem Solving A Student Handbook with Checklists for Successful Critical ThinkingVon EverandSequential Problem Solving A Student Handbook with Checklists for Successful Critical ThinkingBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Teaching Reading Skills Using Authentic Materials: Muhammad RustamDokument14 SeitenTeaching Reading Skills Using Authentic Materials: Muhammad RustamMuhammad Tahir GulzarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Writing MDokument67 SeitenAdvanced Writing MMuhammedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Local Media5836741537061396573Dokument18 SeitenLocal Media5836741537061396573Rose Mae CabraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ReviewDokument3 SeitenReviewMayola SabatiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- WRITINGnABSTRACTnLEVELn6 56637bcbea7a6a2Dokument3 SeitenWRITINGnABSTRACTnLEVELn6 56637bcbea7a6a2chaverrajarodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abstract Precis SummaryDokument6 SeitenAbstract Precis SummaryLeonard Anthony DeladiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RDL - Module 8Dokument19 SeitenRDL - Module 8Padz MaverickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developmental ReadingDokument5 SeitenDevelopmental ReadingMillivet Gail Magracia MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q1: What Are The Types of Assessment? Differentiate Assessment For Training of Learning and As Learning?Dokument14 SeitenQ1: What Are The Types of Assessment? Differentiate Assessment For Training of Learning and As Learning?eng.agkhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ScaffoldingDokument4 SeitenScaffoldingWaluyo Janwar PutraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curs 6 Ped 2 2021-2022Dokument22 SeitenCurs 6 Ped 2 2021-2022Petronela NistorNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSR Strategy Focus of Lesson: Nonfiction Comprehension Grade Level/Subject: 3 Common Core State Standards: CCSS - ELA-LITERACY - RI.3.2 Determine TheDokument4 SeitenCSR Strategy Focus of Lesson: Nonfiction Comprehension Grade Level/Subject: 3 Common Core State Standards: CCSS - ELA-LITERACY - RI.3.2 Determine Theapi-295566988Noch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding by Design Unit TemplateDokument5 SeitenUnderstanding by Design Unit Templateapi-318155534Noch keine Bewertungen

- Implementing The Text Structure Strategy in Your ClassroomDokument7 SeitenImplementing The Text Structure Strategy in Your ClassroomMark A-Jhay TomesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Approaches For WritingDokument4 Seiten3 Approaches For Writingkamran imtiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 13 Reading To LearnDokument9 SeitenChapter 13 Reading To Learncutiecarafos1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ued 495-496 Spivey Stacy Artifact Best Practices HandbookDokument22 SeitenUed 495-496 Spivey Stacy Artifact Best Practices Handbookapi-337457106Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reciprocal TeachingDokument3 SeitenReciprocal TeachingArief Al HakimNoch keine Bewertungen

- fs10 PrintDokument13 Seitenfs10 PrintNix AmrNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write The Introduction of An Action Research PaperDokument8 SeitenHow To Write The Introduction of An Action Research Papergw1qjewwNoch keine Bewertungen

- There Are Ten Basic Skills That AppliedDokument8 SeitenThere Are Ten Basic Skills That AppliedCh ArmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Reading, Comprehension Skills Strategies and Best PracticesDokument7 SeitenRemedial Reading, Comprehension Skills Strategies and Best PracticesLORY ANNE SISTOZANoch keine Bewertungen

- Study SkillsDokument6 SeitenStudy SkillsGuillote RiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading StrategiesDokument31 SeitenReading StrategieszaldymquinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pencil. : Hominid Evolution Through The AgesDokument6 SeitenPencil. : Hominid Evolution Through The Agesapi-266396417Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reciprocal TeachingDokument9 SeitenReciprocal TeachingJohan HanzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edtpa Lesson 2Dokument4 SeitenEdtpa Lesson 2api-273345234Noch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Reading Comprehension Skills For LPDokument4 Seiten5 Reading Comprehension Skills For LPJoan PeridaNoch keine Bewertungen

- M Delbono CM AssignmentDokument11 SeitenM Delbono CM AssignmentNatalia DelbonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course Objectives: Guide, Reader, and Handbook. Edited by James Reinking and Robert Von Der Osten, 11Dokument2 SeitenCourse Objectives: Guide, Reader, and Handbook. Edited by James Reinking and Robert Von Der Osten, 11jeanninestankoNoch keine Bewertungen

- UHCL Fall 2021 TCED 4322 DAP Reflection # 2Dokument13 SeitenUHCL Fall 2021 TCED 4322 DAP Reflection # 2Eleanora T. GalloNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Institute of PGDM With AddressDokument6 SeitenList of Institute of PGDM With AddressSayon DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- InclusionDokument18 SeitenInclusionmiha4adiNoch keine Bewertungen

- GRADE 11 SIMPLICITY MASTER SHEET FinalDokument3 SeitenGRADE 11 SIMPLICITY MASTER SHEET FinalTyronePelJanioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Creativity Skills in Primaryuagc2013Dokument6 SeitenTeaching Creativity Skills in Primaryuagc2013Iancu CezarNoch keine Bewertungen

- TR HEO (On Highway Dump Truck Rigid)Dokument74 SeitenTR HEO (On Highway Dump Truck Rigid)Angee PotNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of ExaminerDokument2 SeitenList of ExaminerndembiekehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Singaplural 2016 Festival MapDokument2 SeitenSingaplural 2016 Festival MapHuyNoch keine Bewertungen

- NQESH Domain 3 With Answer KeyDokument8 SeitenNQESH Domain 3 With Answer Keyrene cona100% (1)

- Padagogy MathsDokument344 SeitenPadagogy MathsRaju JagatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ok Sa Deped Form B (Dsfes)Dokument10 SeitenOk Sa Deped Form B (Dsfes)Maan Bautista100% (2)

- PDF Hope 4 Module 3 - CompressDokument9 SeitenPDF Hope 4 Module 3 - CompressJaymark LigcubanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Za HL 778 Phonics Revision Booklet - Ver - 3Dokument9 SeitenZa HL 778 Phonics Revision Booklet - Ver - 3Ngọc Xuân BùiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test ASDokument3 SeitenTest ASAgrin Febrian PradanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 8-4 Legacy of The RenaissanceDokument3 SeitenModule 8-4 Legacy of The RenaissanceClayton BlaylockNoch keine Bewertungen

- CorrectionsDokument337 SeitenCorrectionsUnited States Militia100% (2)

- Experts, Semantic and Epistemic: S G Northwestern UniversityDokument18 SeitenExperts, Semantic and Epistemic: S G Northwestern UniversityBrian BarreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume CurrentDokument1 SeiteResume Currentapi-489738965Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jamila Joy ResumeDokument2 SeitenJamila Joy ResumeJamila TaguiamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aptitude Test - 100 Aptitude Quiz Questions With AnswersDokument25 SeitenAptitude Test - 100 Aptitude Quiz Questions With AnswersRinga Rose RingaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review Form: Basic Education Service Teaching Learning Process (30%)Dokument3 SeitenIndividual Performance Commitment and Review Form: Basic Education Service Teaching Learning Process (30%)Donita-jane Bangilan CanceranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application Form SaumuDokument4 SeitenApplication Form SaumuSaumu AbdiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Saudi Executive Regulations of Professional Classification and Registration AimsDokument8 SeitenThe Saudi Executive Regulations of Professional Classification and Registration AimsAliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Croft Thesis Prospectus GuideDokument3 SeitenCroft Thesis Prospectus GuideMiguel CentellasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uc Piqs FinalDokument4 SeitenUc Piqs Finalapi-379427121Noch keine Bewertungen

- Form 1 & 2 Lesson Plan CefrDokument3 SeitenForm 1 & 2 Lesson Plan CefrTc NorNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV Main EnglishDokument2 SeitenCV Main EnglishArie KelmachterNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPL Mech Eng Proc 05Dokument20 SeitenRPL Mech Eng Proc 05Federico MachedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transactional and Transformational LeadershipDokument4 SeitenTransactional and Transformational LeadershipAnonymous ZLSyoWhQ7100% (1)

- Math ThesisDokument14 SeitenMath ThesisElreen AyaNoch keine Bewertungen