Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1989 DBQ - Black Americans PDF

Hochgeladen von

deabtegoddOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1989 DBQ - Black Americans PDF

Hochgeladen von

deabtegoddCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

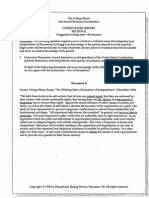

The College Board

Advanced Placement Examination

UNITED STATES HISTORY

SECTION I1

(Suggested writing time--40 minutes)'

Directions: The following question requires you to construct a coherent essay that integrates your

interpretation of Documents A-J d your knowledge of the period referred to in the question. In

your essay, you should strive to support your assertions both by citing key pieces of evidence from

the documents and by drawing on your knowledge of the period.

,

-H

1. Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois offered different strategies for dealing with the

problems of poverty and discrimination faced by Black Americans at the end of the nineteenth

and beginning of the twentieth centuries.

Using the documents and your knowledge of the period 1877-1915, assess the appropriateness

of each of these strategies in the historical context in which each was developed.

Document A

SCHOOL ENROLLMENT BY RACE

70

60

3

White People

'

.ti 50-

a"

5r

m

40 -

$

C n

30-

LD

*

0

0)

s5!

CI

2010-

+

I

@ C\O 0Q 9Q QQ

,e

, e , e , e , 9 , 9 , 9ctO

Document B

ILLITERACY BY RACE

Q,

60

8s 50

%:

Native-born White People

40

8%

30

&

:, 20

a 0

g ISb 10

k c

"03

Y

84

k"

Document C

LYNCHINGS BY RACE

,

170

10

0

I

1882 1885

1890

1895

1900

1905

1910

1915

Document D

Source: Booker T. Washington, "Atlanta Compromise Address" (September 11,1895)

"To those of the white race who look to the incoming of those of foreign birth and strange tongue

'

and habits for the prosperity of the South, were I permitted I would repeat what I say to my own

race, 'Cast down your bucket where you are.' Cast it down among the eight millions of Negroes

whose habits you know, whose fidelity and love you have tested in days when to have proved

treacherous meant the ruin of your firesides. Cast down your bucket among these people who have,

without strikes and labor wars, tilled your fields, cleared your forests, built your railroads and cities,

and brought forth treasures from the bowels of the earth, and helped make possible this magnificent

representation of the progress of the South. Casting down your bucket among my people, helping

and encouraging them as you are doing on these grounds, and to education of head, hand, and

heart, you will find that they will buy your surplus land, make blossom the waste places in your

fields, and run your factories. While doing this, you can be sure in the future, as in the past, that you

and your families will be surrounded by the most patient, faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful

people that the world has seen. As we have proved our loyalty to you in the past, in nursing your

children, watching by the sickbed of your mothers and fathers, and often following them with teardimmed eyes to their graves, so in the future, in our humble way, we shall stand by you with a

devotion that no foreigner can approach, ready to lay down o h lives, if need be, in defense of yours,

interlacing our industrial, commercial, civil, and religious life with yours in a way that shall make

the interests 6f both races one. In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the

fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress. . . .

"The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the

extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be

the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing. No race that has anything

to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right

that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the

exercises of these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house."

Document E

Source: W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

"Is it possible and

that nine millions of men can make effective progress in economic lines

if they are deprived of political rights, made a servile caste, and allowed only the most meagre

chance for developing their exceptional men? If history and reason give any distinct answer to

these questions it is an emphatic No. . . .

"Such men, [the thinking classes of American Negroes] feel in conscience bound to ask of this nation

three things:

1.

2.

3.

The right to vote

Civic equality

The education of youth according to ability

"They do not expect that the free right to vote, to enjoy civic rights, and to be educated, will come

in a moment; they do not expect to see the bias and prejudices of years disappear at the blast of a

trumpet; but they are absolutely certain that the way for a people to gain their reasonable rights is

not by voluntarily throwing them away and insisting that they do not want them; that the way for

a people to gain respect is not by continually belittling and ridiculing themselves; tKat, on the

contrary, Negroes must insist continually, in season and out of season, that voting is necessary to

modem manhood, that color discrimination is barbarism, and that black boys need education as

well as white boys."

Document F

Source: W.E.B. Du Bois, "The Niagara Movement," Voice of the Negro I1 (September 1905)

"There has been a determined effort in this country to stop the free expression of opinion among

black men; money has been and is being distributed in considerable sums to influence the attitude of

certain Negro papers; the principles of democratic government are losing ground, and caste distinctions are growing in all directions. Huinan brotherhood is spoken of today with a smile and a sneer;

effort is being made to curtail the educational opportunities of the colored children; and while much

is said about moneymaking, not enough is said about efficient, self-sacrificing toil of head and hand.

Are not all these things worth striving for? The Niagara Movement proposes to gain these ends. . . . If

we expect to gain our rights by nerveless acquiescence in wrong, then we expect to do what no other

nation ever did. What must we do then? We must complain. Yes, plain, blunt complain, ceaseless

agitation, unfailing exposure of dishonesty and wrong-this is the ancient, unerring way to liberty,

and we must follow it."

Document G

Source: T. Thomas Fortune, a Black activist and newspaper editor, writing in the nationally circulated Black periodical, Christian Recorder (May 15,1890)

"I have spent a week at Tuskegee, forty miles from Montgomery, investigating and studying the

great work being done here, in the Tuskegee Normal [Teacher Training] and Industrial Institute, of

which Mr. Booker T. Washington is the originator and projector. . . .

//

"Here we have under control a thousand acres of land; here we have 400 colored song, drinking in

knowledge from the faithful ministrations of twenty-eight colored teachers, male and female. A

more interesting spectacle can no where else be seen and studied. . . . Splendid farm equipments,

stock-raising, fruit culture, laundry work, practical housekeeping in all its branches, blacksmithing,

wheelwrighting, carpentering, printing and building, shoe and harness making, masonry are all

taught in their practical forms, while a splendid Normal school system is maintained to prepare

school teachers for the great work before.them. . . .

"No time is wasted on dead languages or superfluous studies of any kind. What is practical, what

will best fit these young people for the work of life, that is taught, and that is aimed at. Nor is moral

and religious culture neglected. . . . It is impossible to estimate the value of such a man as Booker T.

Washington."

Document H

Source: Ida Wells Barnett, a Black civil rights activist, feminist, and newspaper editor, "Booker T.

Washington and His Critics" (1904)

"Industrial education for the Negro is Booker T. Washington's hobby. . . .

/j

"That one of the most noted of their own race should join with the enemies to their highest progress in condemning the education they had received, has been to . . . [college educated Negroes]

a bitter pill. . . .

"No human agency can tell how many black diamonds lie buried in the black belt of the South, and

the opportunities for discovering them become rarer every day as the schools for thorough training

become more cramped and no more are being established.

"Does this mean that the Negro objects to industrial education? By no means. It simply means that

he knows by sad experience that industrial education will not stand him in place of political, civil

and intellectual liberty, and he objects to being deprived of fundamental rights of American citizenship to the end that one school for industrial training shall flourish. To him it seems like selling a

race's birthright for a mess of pottage."

Document I

Source: Carter Woodson, a Black historian and educator, The Mis-education of the Negro (1933)

"Neither this inadequately supported [industrial education] school system nor the struggling higher

institutions of a classical order established about the same time . . connected the Negroes very

closely with life as it was. These institutions were concerned rather with life as they hoped to make

it. When the Negro found himself deprived of influence in politics, therefore, and at the same time

unprepared to participate in the higher functions in the industrial development which this country

began to undergo, it soon became evident to him that he was losing ground in the basic things of

life. He was spending his time studying about the things which had been or might be, but he was

learning little to help him to do better the tasks at hand."

Document J

Source: The Bettmann Archive

END OF 1989 DBQ DOCUMENTS

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Undoing Monogamy by Angela WilleyDokument38 SeitenUndoing Monogamy by Angela WilleyDuke University Press100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- First Sino-Japanese War PDFDokument20 SeitenFirst Sino-Japanese War PDFdzimmer60% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Bisexual Invisibility Impacts and Recommendations (Adopted March 2011)Dokument47 SeitenBisexual Invisibility Impacts and Recommendations (Adopted March 2011)Cecilia C Chung100% (1)

- CA in KolkataDokument8 SeitenCA in KolkatananiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eritrea-Ethiopia War (1998-2000)Dokument30 SeitenEritrea-Ethiopia War (1998-2000)Hywel Sedgwick-Jell100% (1)

- Marriage, Past and Present: A Debate Between Robert Bruffault and Bronislaw MalinowskiDokument104 SeitenMarriage, Past and Present: A Debate Between Robert Bruffault and Bronislaw Malinowskilithren100% (1)

- 【Carl Schmitt】Crisis of parliamentary DemocracyDokument269 Seiten【Carl Schmitt】Crisis of parliamentary Democracy江威儀50% (2)

- Senarai Nama Yang Berminat Suntikan VaksinDokument4 SeitenSenarai Nama Yang Berminat Suntikan Vaksinrahimi67Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cme100 Matlab WorkbookDokument31 SeitenCme100 Matlab WorkbookdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 4 Iran - Political InstitutionsDokument9 SeitenLesson 4 Iran - Political InstitutionsdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 1 Iran - Sovereignty Authority and Power-HomeDokument7 SeitenLesson 1 Iran - Sovereignty Authority and Power-HomedeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3 Iran - Citizens Society and The State-HomeDokument9 SeitenLesson 3 Iran - Citizens Society and The State-HomedeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 5 Iran - Government Institutions-HomeDokument17 SeitenLesson 5 Iran - Government Institutions-HomedeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 2 Iran - Political and Economic ChangeDokument3 SeitenLesson 2 Iran - Political and Economic ChangedeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 6 Iran - Public Policy and Current Issues-HomeDokument9 SeitenLesson 6 Iran - Public Policy and Current Issues-HomedeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Period 8 FlashcardsDokument4 SeitenPeriod 8 FlashcardsdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Period 5 FlashcardsDokument4 SeitenPeriod 5 FlashcardsdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why 1865 - 1898 Was Chosen As The Dates For Period 6 Gilded AgeDokument4 SeitenWhy 1865 - 1898 Was Chosen As The Dates For Period 6 Gilded AgedeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Period 7 FlashcardsDokument4 SeitenPeriod 7 FlashcardsdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Period 9 FlashcardsDokument4 SeitenPeriod 9 FlashcardsdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Period 1 FlashcardsDokument4 SeitenPeriod 1 FlashcardsdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Period 4 FlashcardsDokument4 SeitenPeriod 4 FlashcardsdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1992 DBQ - Settlement of The West PDFDokument5 Seiten1992 DBQ - Settlement of The West PDFdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jacksonian Democracy DBQDokument5 SeitenJacksonian Democracy DBQNick RNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1993 DBQ - Two Societies PDFDokument6 Seiten1993 DBQ - Two Societies PDFdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1995 DBQ - Civil RightsDokument6 Seiten1995 DBQ - Civil RightsMelissa NgNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1994 DBQ - ImperialismDokument6 Seiten1994 DBQ - ImperialismAPclassHelpNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1991 DBQ - Treaty of VersaillesDokument4 Seiten1991 DBQ - Treaty of VersaillesAndrew McGowanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1983 DBQ - Populists PDFDokument6 Seiten1983 DBQ - Populists PDFdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1988 DBQ - Dropping The Atomic Bomb PDFDokument5 Seiten1988 DBQ - Dropping The Atomic Bomb PDFdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1987 DBQ - Compromise of 1850Dokument7 Seiten1987 DBQ - Compromise of 1850psppunk7182Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cap KritiqueDokument21 SeitenCap KritiquedeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oil Exploration Negative - CDL 2014Dokument19 SeitenOil Exploration Negative - CDL 2014deabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1988 DBQ - Dropping The Atomic Bomb PDFDokument5 Seiten1988 DBQ - Dropping The Atomic Bomb PDFdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropocentrism Critique - CDL 2014Dokument24 SeitenAnthropocentrism Critique - CDL 2014deabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Offshore Wind Negative - CDL 2014Dokument16 SeitenOffshore Wind Negative - CDL 2014deabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mapping Case Neg - DDI 2014 TWDokument19 SeitenMapping Case Neg - DDI 2014 TWdeabtegoddNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sailing Schedule UpdatedDokument7 SeitenSailing Schedule UpdatedEileen ChavestaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pardo de Tavera's Account of The Cavite MutinyDokument1 SeitePardo de Tavera's Account of The Cavite Mutiny202280369Noch keine Bewertungen

- Working Paper For The ResolutionDokument3 SeitenWorking Paper For The ResolutionAnurag SahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Percentage of Blacks Incarcerated Vs PopulationDokument1 SeitePercentage of Blacks Incarcerated Vs PopulationMiss Anne100% (2)

- The LetterDokument10 SeitenThe Letterderrick marfoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macalintal Vs PET - DigestDokument1 SeiteMacalintal Vs PET - DigestKristell FerrerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7666 - CCM Gopalpur As Training CentreDokument2 Seiten7666 - CCM Gopalpur As Training CentreCredit SectionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cyber Bullying in The PhilippinesDokument2 SeitenCyber Bullying in The PhilippinesNaja GamingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ra 10911Dokument2 SeitenRa 10911Nathaniel OlaguerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 00001t TifDokument342 Seiten00001t TifjamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Freaking The Old Man and The SeaDokument5 SeitenThe Freaking The Old Man and The Seaapi-295683290Noch keine Bewertungen

- President of India Is A Rubber Stamp or NotDokument19 SeitenPresident of India Is A Rubber Stamp or Noturvesh bhardwajNoch keine Bewertungen

- PURAL - ReflectionDokument1 SeitePURAL - ReflectionJohn Braynel PuralNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Forms Legal Memorandum: Atty. Daniel LisingDokument7 SeitenLegal Forms Legal Memorandum: Atty. Daniel LisingAlyssa MarañoNoch keine Bewertungen

- In This Essay of RizalDokument1 SeiteIn This Essay of RizalShawn LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baby Names Australia Report 2021Dokument18 SeitenBaby Names Australia Report 2021Daniel millerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hind Swaraj - LitCharts Study GuideDokument37 SeitenHind Swaraj - LitCharts Study GuideJoyce AbdelmessihNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal FalinDokument19 SeitenJurnal Falindini100% (1)

- Lesson 2 Applied EconomicsDokument2 SeitenLesson 2 Applied EconomicsMarilyn DizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- China's Belt and Road Initiative and Its Implications For Global DevelopmentDokument28 SeitenChina's Belt and Road Initiative and Its Implications For Global DevelopmentjayaravinthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Should The Philippines Turn Parliamentary by Butch AbadDokument19 SeitenShould The Philippines Turn Parliamentary by Butch AbadBlogWatch100% (1)

- Elaine ShowalterDokument4 SeitenElaine ShowalterFlávia RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen