Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Spiny Lobster Fishery in Honduras

Hochgeladen von

Evelyn Rodriguez MejiaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Spiny Lobster Fishery in Honduras

Hochgeladen von

Evelyn Rodriguez MejiaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ENS747 Marine Resources Management

Spiny Lobster Fishery in Honduras

A review of the fisherys state

The Caribbean spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) is one of the commercial fished

invertebrates in Honduras. This fishery represents an important income for the country

through its exports to the United States. However, besides the revenue and

employment opportunities this fishery produce, the environmental and social effects

of the fishery cannot be dismissed.

P. argus is fished in Honduras by artisanal and industrial fleets using traps and by

diving with the use of casitas and/or SCUBA gear (Sullivan, 2013; WWF, 2004).

Artisanal fishing practices are performed and owned by the Miskito1 people; while the

industrial fleets are usually owned by fishing companies that hire Miskito fishermen (El

Heraldo, 2013). Most of the fishery stock is fished, processed, and exported to the

United States by the industrial fleets. In 2013, this fishery produced a total of 3.6

million pounds with a value of about 42.2 million dollars in exports, mainly to the US

market. In addition, it generated 3,840 direct jobs in a total of 121 fishing boats (La

Tribuna, 2014).

Regulations for this fishery follow the bylaw from OSPESCA2. Regulation OSP-02-09

establishes the catch-size, catch practices, and moratorium period, for the spiny

lobster fishery in the six Central American nations (La Tribuna, 2014; USAID, 2011). The

government body in charge of monitoring the fishery and enforcing its regulations in

Honduras is DIGEPESCA3 (regulations applicable to Honduras are shown in Table 1).

However, DIGEPESCA has shown weaknesses in the fulfillment of its duties; for which,

as in many developing countries, international cooperation agencies (e.g. WWF,

USAID, Global Fish Alliance, etc.) have had to provide support with the aim of achieving

sustainability. DIGEPESCA has had difficulties on being efficient in controlling and

managing: 1) the catch of juveniles, 2) the catch of female with eggs, 3) fishing

practices (e.g. size and number of traps per boat, fishing techniques, SCUBA diving and

decompression accidents), 4) stock assessments, and 5) marine protected areas

important for the life-cycle of the species (Beltrn, 2011; El Heraldo, 2013; SosaCordero, 2010; Sullivan 2013; US Department of Justice, 2011).

Miskito is one of the ethnic groups of Honduras.

OSPESCA - Agency of Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector of the Central American Isthmus

3

DIGEPESCA - Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture

2

Evelyn H. Rodrguez

ENS747 Marine Resources Management

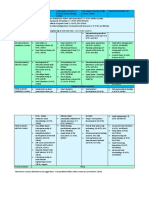

Table 1. Regulations for the spiny lobster fishery in Honduras

Adapted from USAID (2011)

Regulation aspects

Prohibitions

Moratorium period from March 1

Capture, possession, and trade of

to June 30.

spawning females

Catch size >145mm tail length

Removal of eggs from females

Boats dimensions (artisanal and

Commercialization of processed meat

industrial)

Traps dimensions and materials

Transport and handling of catch

One of the main issues faced by the spiny lobster fishery in Honduras is the illegal

catch of juveniles and spawning females (WWF, 2006). Previous stock assessments

(e.g. Chvez, 2001; Sosa-Cordero, 2010) have found that in Honduras juvenile lobsters

are being over-exploited. Likewise, cases of lobster smuggling into the United States

where juveniles and spawning females are the largest percentage of the shiploads are

common (US Department of Justice, 2011). These practices lead to an imbalance in the

spiny lobster life-cycle (Figure 1) which later on can cause negative effects on the

population dynamics of the species and the fishing industry (Pandolfi et al, 2005;

WWF, 2006). For instance, Sosa-Cordero (2010) reports that for the years 2009-2010

big adult lobsters (7-8 years) were absent. This is significantly important when

compared to Maxwell et al. (2013) findings in which age and size of lobsters are

positively correlated to egg production. As younger/smaller females are producing

fewer eggs, the future population numbers could be expected to decrease.

Figure 1. Life-cycle of Panulirus argus

Adapted from Miller, Ohs & Creswell (2007) and Dunhar & Sjoboen (2005)

Evelyn H. Rodrguez

ENS747 Marine Resources Management

Consequently, the current decline in the spiny lobster fisherys productivity,

particularly in terms of overall lobster catches and the performance of the fishing

industry (El Heraldo, 2013; WWF 2004) are not a surprise. For instance, fishermen

reports that now they are catching smaller numbers of lobsters while making bigger

efforts (i.e. longer trips and more/deeper dives) (El Heraldo, 2013). As a result,

concerns about the fisheries sustainability, productivity and ecosystem health have

risen (Sosa-Cordero, 2010; WWF, 2004).

While it is clear that the countrys conditions (e.g. poverty, corruption, lack of

knowledge, institutional weakness, limited resources, etc.) are not the best to provide

an adequate and sustainable management of the spiny lobster fishery; efforts for

increasing stock assessments, reducing fishing effort, monitoring of species recovery

and management of species habitat should be enforced if fishery decline is to be

avoided (Dunhar & Sjoboen, 2005; Linnane, Sloan, McGarvey, & Ward, 2010). Lessons

from other fishing sites in the Caribbean and Australia can be applied in Honduras (e.g.

Ley-Cooper et al., 2014; Linnane et al. 2010; Maxwell et al., 2013).

Habitat management through the use of no-take marine reserves has proven that

species recovery can be attained without compromising the industry. Ley-Cooper et al.

(2014) and Maxwell et al. (2013) state that no-take reserves present greater lobster

size and higher egg production than fishing areas. Particularly important is the fact that

a percentage of the lobster from no-take reserves usually migrate to fishing areas (LeyCooper et al., 2014); providing the industry with higher value product. However, while

the declaration of no-take reserves in Honduras may not be embraced by the public

and especially by the Miskito people (Agardy et al., 2003); the prohibition of fishing

with SCUBA diving gear leads to the subtle establishment of no-take reserves in deeper

waters (Ley-Cooper et al., 2014). This can also be a social improvement for the Miskito

fishermen who are exposed to decompression accidents due to unregulated diving

practices (Beltrn, 2011; El Heraldo, 2013); and a boost to the artisanal fishermen who

compete against the industrial fleets.

On the other hand, Linnane et al. (2010) states that the lack of management actions

aiming at reducing fishing efforts is associated to fishery decline. In this context,

DIGEPESCA could modify the current regulations applicable to the spiny lobster fishery.

For example, an extension of the moratorium period from 4 to 5 months would not

only reduce the fishing effort and pressure on the species population but also the

likelihood of fishing ovigerous females.

In conclusion, the current status of the spiny lobster fishery in Honduras does not fit as

sustainable fishery. However, while the fishery is not yet depleted signs of overexploitation (particularly for juvenile lobsters) are widely present. Enforcement of

regulations for a better habitat management and fishing practicesincluding control

Evelyn H. Rodrguez

ENS747 Marine Resources Management

of fishing effortsare needed to improve the current state of the fishery and to

achieve sustainability.

References

Agardy, T. et al. (2003). Dangerous targets? Unresolved issues and ideological clashes

around marine protected areas. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater

Ecosystems 13, 353-367.

Beltrn, C. (2011). Value-chain analysis of international fish trade and food security in

the Republic of Honduras. Fisheries And Aquaculture Department Products,

Trade And Marketing (FIPM). El Salvador: FAO.

Chvez, E. A. (2001). Policy Design for Spiny Lobster (Panulirus argus) Management at

the Meso-American Barrier Reef System. Crustaceana, 74(10), 1119-1137.

Dunhar, S. & Sjoboen, A. (2005). Roatn Rapid Assessment for the Caribbean spiny

lobster , Panulirus argus. Roatn, Bay Islands, Honduras: USAID/MIRA.

El Heraldo. (2013, July 14). Buzos langosteros de La Mosquitia desafan a la muerte

para sobrevivir, El Heraldo. Retrieved from

http://www.elheraldo.hn/Secciones-Principales/Al-Frente/Buzos-langosterosde-La-Mosquitia-desafian-a-la-muerte-para-sobrevivir

La Tribuna. (2014, July 1). Fin de la veda de langosta en el Caribe Hondureo, La

Tribuna. Retrieved from http://www.latribuna.hn/2014/07/01/fin-de-la-vedade-langosta-en-el-caribe-hondureno/

Linnane, A., Sloan, S., McGarvey, R., & Ward, T. (2010). Impacts of unconstrained

effort: Lessons from a rock lobster (Jasus edwardsii) fishery decline in the

northern zone management region of South Australia. Marine Policy, 34(5),

844-850.

Ley-Cooper, K., De Lestang, S., Phillips, B. F., & Lozano-lvarez, E. (2014). An unfished

area enhances a spiny lobster, Panulirus argus, fishery: Implications for

management and conservation within a Biosphere Reserve in the Mexican

Caribbean. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 21(4), 264-274.

Maxwell, K. et al. (2013). Age and size structure of Caribbean spiny lobster, Panulirus

argus, in a no-take marine reserve in the Florida Keys, USA. Fisheries Research,

144, 84-90.

Pandolfi et al. (2005, March 18). Are U.S. Coral Reefs on the Slippery Slope to Slime?

Science Magazine 307, 1725-1726. AAAS

Sosa-Cordero, E. (2010). Evaluacin del recurso langosta Panulirus argus en la

plataforma de Honduras y Nicaragua, a partir de datos del programa de

observadores colectados en dos temporadas 2007-2008; 2009- 2010. USAID &

WWF: Mxico.

Sullivan, M. (2013). Caribbean Spiny Lobster. Bahamas, Belize, Brazil, Honduras, and

Nicaragua - Traps, Diving with Use of Casitas. Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood

Watch

Evelyn H. Rodrguez

ENS747 Marine Resources Management

USAID. (2011). Good Fishing Practices Manual. Retrieved from

http://digepesca.sag.gob.hn/assets/display-anything/gallery/1/522/BuenasPracticas-Pesqueras.pdf

US Department of Justice. (2011). US v. David Henson McNab et al., 324 F.3d 1266,

amended and superseded on rehearing by 331 F.3d 1228 (11th Cir. 2003), cert.

denied, 540 U.S. 1177 (2004). Retrieved from

http://www.justice.gov/enrd/3326.htm

WWF. (2004). Spiny Lobster Marketing Chain. Costa Rica: WWF Central America.

WWF. (2006). Cmo lograr mayores ingresos pescando de manera sustentable. Manual

de Prcticas Pesqueras de Langosta en el Arrecife Mesoamericano. WWFMxico/Centroamrica. 97 pp.

Evelyn H. Rodrguez

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Marine Mammals: Fisheries, Tourism and Management Issues: Fisheries, Tourism and Management IssuesVon EverandMarine Mammals: Fisheries, Tourism and Management Issues: Fisheries, Tourism and Management IssuesNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISRS Briefing Paper 1 - Marine Protected AreasDokument13 SeitenISRS Briefing Paper 1 - Marine Protected AreastreesandseasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asian Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development: Vlademir A. ShuckDokument15 SeitenAsian Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development: Vlademir A. ShuckKarl KiwisNoch keine Bewertungen

- tmp3359 TMPDokument12 Seitentmp3359 TMPFrontiersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Where Small Can Have A Large Impact Structure and Characterization of Small Scale Fisheries in Peru. Alfaro Shigueto, Joanna-2010Dokument10 SeitenWhere Small Can Have A Large Impact Structure and Characterization of Small Scale Fisheries in Peru. Alfaro Shigueto, Joanna-2010Yomira Leon Santa CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biological ConservationDokument14 SeitenBiological ConservationIonela ConstandacheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept PaperDokument3 SeitenConcept PaperJenjen Mopal100% (1)

- Incidental Catch of Marine Mammals in The Southwest Indian Ocean: A Preliminary ReviewDokument11 SeitenIncidental Catch of Marine Mammals in The Southwest Indian Ocean: A Preliminary ReviewC3publicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2010 - Clua Et Al. Behavioural Response of LS To FeedingDokument10 Seiten2010 - Clua Et Al. Behavioural Response of LS To FeedingKaro ZuñigaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davidson Et Al-2015-Fish and FisheriesDokument21 SeitenDavidson Et Al-2015-Fish and Fisheriessqualljavier612Noch keine Bewertungen

- metodo cientificoDokument15 Seitenmetodo cientificoariatarazonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marine Policy 40 (2013) Global Catches, Exploitation Rates, and Rebuilding Options For SharksDokument11 SeitenMarine Policy 40 (2013) Global Catches, Exploitation Rates, and Rebuilding Options For SharksaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Substantial Impacts of Subsistence Fishing On The Population Status of An Endangered Reef Predator at A Remote Coral AtollDokument11 SeitenSubstantial Impacts of Subsistence Fishing On The Population Status of An Endangered Reef Predator at A Remote Coral AtollGoresan RimbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Species of Concern Dusky Shark: NOAA National Marine Fisheries ServiceDokument5 SeitenSpecies of Concern Dusky Shark: NOAA National Marine Fisheries ServiceJessica MarieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainability of Capture of Fish Bycatch in The Prawn Trawling in The Northeastern BrazilDokument10 SeitenSustainability of Capture of Fish Bycatch in The Prawn Trawling in The Northeastern BrazilCarlos JúniorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reducing Sea Turtle Bycatch in Ecuadorian GillnetsDokument10 SeitenReducing Sea Turtle Bycatch in Ecuadorian GillnetsclaraoaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diversity RevisedDokument28 SeitenDiversity Revisedestella erayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecuador Final PaperDokument19 SeitenEcuador Final Paperapi-315909409Noch keine Bewertungen

- International Maritime University of PanamaDokument7 SeitenInternational Maritime University of PanamaYeicob PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fishes 09 00002 v2Dokument30 SeitenFishes 09 00002 v2Satrio Hani SamudraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic challenges facing small-scale coastal fishing societiesDokument4 SeitenEconomic challenges facing small-scale coastal fishing societiesankitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anderson 20 Perspectives 2017!2!20 MREDokument19 SeitenAnderson 20 Perspectives 2017!2!20 MREKristine San MartínNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overfishing Causes Decline of Fish PopulationsDokument4 SeitenOverfishing Causes Decline of Fish Populationsaccounting280Noch keine Bewertungen

- Iotc 2012 Wpeb08 30Dokument14 SeitenIotc 2012 Wpeb08 30sheriefmuhammedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Sardinella Fisheries Legislation in BulanDokument72 SeitenImpact of Sardinella Fisheries Legislation in BulanEllen Grace GojoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overfishing NorwayDokument10 SeitenOverfishing Norwayapi-609383566Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Intrinsic Vulnerability To Fishing of Coral Reef Fishes and Their Differential Recovery in Fishery ClosuresDokument32 SeitenThe Intrinsic Vulnerability To Fishing of Coral Reef Fishes and Their Differential Recovery in Fishery ClosuressdfhadfhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fresh WaterDokument5 SeitenFresh Wateryasahswi91Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fisheries Research: Haemulon Plumierii) in The CaribbeanDokument9 SeitenFisheries Research: Haemulon Plumierii) in The Caribbeanstar warsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Fisheries Research BelizeDokument3 SeitenCommunity Fisheries Research BelizeDanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faf 12469Dokument10 SeitenFaf 12469YJLNoch keine Bewertungen

- 113 227 1 SMDokument10 Seiten113 227 1 SMindaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Destruction of Coral ReefsDokument14 SeitenThe Destruction of Coral ReefsGilliane del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seafood Watch Orange Roughy ReportDokument17 SeitenSeafood Watch Orange Roughy ReportMonterey Bay AquariumNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENS 203-IAS Profile - Natividad FinalDokument7 SeitenENS 203-IAS Profile - Natividad FinalRaysolyn NatividadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Circle HooksDokument11 SeitenCircle HooksSepri JayapuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The State of The Science - Forage Fish in The California Current.Dokument20 SeitenThe State of The Science - Forage Fish in The California Current.PewEnvironmentGroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2022 02 DMSD Kondisi SumberdayaDokument44 Seiten2022 02 DMSD Kondisi SumberdayaRiangga Afif AmrullohNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainable FishingDokument12 SeitenSustainable Fishingapi-609383566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Geo Isp: 10 Questions To Be InvestigatedDokument2 SeitenGeo Isp: 10 Questions To Be InvestigatedPenny ALegitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biological Conservation: L. Pichegru, P.G. Ryan, R. Van Eeden, T. Reid, D. Grémillet, R. WanlessDokument9 SeitenBiological Conservation: L. Pichegru, P.G. Ryan, R. Van Eeden, T. Reid, D. Grémillet, R. WanlessIonela ConstandacheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 11Dokument24 SeitenChapter 11kimik47Noch keine Bewertungen

- Diversity and Distribution of Freshwater Fishes at Sungai Muar, Kuala Pilah, Negeri SembilanDokument13 SeitenDiversity and Distribution of Freshwater Fishes at Sungai Muar, Kuala Pilah, Negeri SembilanThanakumaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artigo 5 - ComprovanteDokument8 SeitenArtigo 5 - ComprovanteThiago DiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medina-Vogel Et Al. - in PressDokument8 SeitenMedina-Vogel Et Al. - in PressMar InteriorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coral Reef Fishes Submitted 071405Dokument38 SeitenCoral Reef Fishes Submitted 071405Oliver PaderangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TMP F464Dokument8 SeitenTMP F464FrontiersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contenido Estomacal USA FloridaDokument19 SeitenContenido Estomacal USA FloridaRuth Vasquez LevyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2002 - The Benefits and Risks of Aquacultural Production For The Aquarium TradeDokument17 Seiten2002 - The Benefits and Risks of Aquacultural Production For The Aquarium TradeFabrício BarrosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Determining Sexual Development and Size at Sexual Maturity of Sardinella Tawilis and Its Implications On ManagementDokument16 SeitenDetermining Sexual Development and Size at Sexual Maturity of Sardinella Tawilis and Its Implications On ManagementRichiel SungaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 - 1620 - F1 MatheusDokument11 Seiten01 - 1620 - F1 MatheusIlver AlabatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Impacts and Causation of Beached' Drifting FishDokument15 SeitenEnvironmental Impacts and Causation of Beached' Drifting Fishbahtiar tiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commercial Fishing AND Marine Protected Areas: Environmental Resource Management 413W Malcolm Taylor April 12, 2012Dokument28 SeitenCommercial Fishing AND Marine Protected Areas: Environmental Resource Management 413W Malcolm Taylor April 12, 2012Lisa BoudemanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of The Grouper Export Trade in IndonesiaDokument16 SeitenManagement of The Grouper Export Trade in IndonesiaDito ZhafranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Sea Turtle Conservation SuccessesDokument8 SeitenGlobal Sea Turtle Conservation SuccessesadamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bierypauly SharkfinDokument35 SeitenBierypauly SharkfinAntonio Queiroz LezamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fisheries Oceanography - 2016 - Frusher - From Physics To Fish To Folk Supporting Coastal Regional Communities ToDokument10 SeitenFisheries Oceanography - 2016 - Frusher - From Physics To Fish To Folk Supporting Coastal Regional Communities ToDeenar Tunas RancakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decline Dolphines TourismDokument8 SeitenDecline Dolphines TourismArroyo GramajoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overfishing Final PaperDokument9 SeitenOverfishing Final Paperapi-336665992Noch keine Bewertungen

- González-Wevar...Vargas-Chacoff Et Al 2015 J of HeredityDokument9 SeitenGonzález-Wevar...Vargas-Chacoff Et Al 2015 J of HeredityGabo DaboNoch keine Bewertungen

- No Name Product Address Contact Link PT Edmarmandir I JayaDokument2 SeitenNo Name Product Address Contact Link PT Edmarmandir I JayaKharisma NugrohoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Problems and Prospects of Women Fish Vendors in RamanthuraiDokument4 SeitenA Study On Problems and Prospects of Women Fish Vendors in RamanthuraiInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management100% (1)

- Barrick Gold Corporation - CaseDokument14 SeitenBarrick Gold Corporation - Casekane eveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report On The Eel Stock and FisheryDokument60 SeitenReport On The Eel Stock and FisheryamfipolitisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pengaruh Padat Tebar Terhadap Pertumbuhan Dan Kelangsungan Hidup Ikan Nilem Ukuran 2-3 CM Yang Dipelihara Dalam Happa Di KolamDokument9 SeitenPengaruh Padat Tebar Terhadap Pertumbuhan Dan Kelangsungan Hidup Ikan Nilem Ukuran 2-3 CM Yang Dipelihara Dalam Happa Di KolamAji FirdausNoch keine Bewertungen

- SW Oregon Wild Winter Steelhead Fishery Comment and AttachmentsDokument55 SeitenSW Oregon Wild Winter Steelhead Fishery Comment and AttachmentsMarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isihskipper January 2010Dokument25 SeitenIsihskipper January 2010enelcharcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fishing in PakistanDokument37 SeitenFishing in PakistanEman HassanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0521859255Dokument522 Seiten0521859255Nicolae BadulescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Summary Lanuza Bay RevisedDokument2 SeitenExecutive Summary Lanuza Bay RevisedMartin BorjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ocean Geographic Issue 29 2014Dokument100 SeitenOcean Geographic Issue 29 2014RianPermana1100% (1)

- AgricultureDokument16 SeitenAgricultureUmar MuhammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- BFRI at A Glance PDFDokument14 SeitenBFRI at A Glance PDFshowaib noorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adp Kilifi 2017-2018 - LatestDokument244 SeitenAdp Kilifi 2017-2018 - LatestotiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mill Creek Guide Book Layout DraftDokument15 SeitenMill Creek Guide Book Layout DraftAdam ClarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposal Fish PlanDokument17 SeitenProposal Fish Planakyadav123100% (1)

- (Fish Capture) Hand Instrument and Its VariationDokument24 Seiten(Fish Capture) Hand Instrument and Its VariationKristine Hinayon CarpioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2011-2012 Saltwater RegulationsDokument16 Seiten2011-2012 Saltwater RegulationsFlorida Fish and Wildlife Conservation CommissionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fishconsult Org P 12739Dokument6 SeitenFishconsult Org P 12739Kheme VitoumetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overfishing Our OceansDokument3 SeitenOverfishing Our OceansKai MillerNoch keine Bewertungen

- BBUS 470 Netptute Gourment Seafood CaseDokument10 SeitenBBUS 470 Netptute Gourment Seafood CaseJohny FaulkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of The Proportion of Small Pelagic Fish Species in The 713 Fisheries Management Area Using Purse Seine Gear in South Sulawesi IndonesiaDokument8 SeitenAnalysis of The Proportion of Small Pelagic Fish Species in The 713 Fisheries Management Area Using Purse Seine Gear in South Sulawesi IndonesiaMuhammad Aldi HatmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overview Courses AQFood Juli 2018Dokument2 SeitenOverview Courses AQFood Juli 2018Aini ZahraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Particle BaitsDokument4 SeitenParticle Baitsmarius fNoch keine Bewertungen

- FISH TALES March 2020Dokument8 SeitenFISH TALES March 2020Indrajith AttanayakeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alberta Specified Penalty Listing - May 2017Dokument319 SeitenAlberta Specified Penalty Listing - May 2017edmontonbikesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment in MapehDokument5 SeitenAssignment in Mapehramil_sanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chona Data 2Dokument24 SeitenChona Data 2Justhy NaciloanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBA Seafood Watch Sushi GuideDokument1 SeiteMBA Seafood Watch Sushi GuidepeanutmilkNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Zealand Aquaculture MagazineDokument16 SeitenNew Zealand Aquaculture MagazinefdlabNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They CommunicateVon EverandThe Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They CommunicateBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1002)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingVon EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (4)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingVon EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (31)

- The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildVon EverandThe Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (44)

- The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorVon EverandThe Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (137)

- The Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsVon EverandThe Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (63)

- Come Back, Como: Winning the Heart of a Reluctant DogVon EverandCome Back, Como: Winning the Heart of a Reluctant DogBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (10)

- Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldVon EverandWayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (18)

- World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other AstonishmentsVon EverandWorld of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other AstonishmentsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (221)

- The Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal IntelligenceVon EverandThe Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal IntelligenceBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (11)

- The Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanVon EverandThe Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes us Happier, Healthier, and More CreativeVon EverandThe Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes us Happier, Healthier, and More CreativeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (157)

- Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of MossesVon EverandGathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of MossesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (347)

- The Big, Bad Book of Botany: The World's Most Fascinating FloraVon EverandThe Big, Bad Book of Botany: The World's Most Fascinating FloraBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (10)

- A Garden of Marvels: How We Discovered that Flowers Have Sex, Leaves Eat Air, and Other Secrets of PlantsVon EverandA Garden of Marvels: How We Discovered that Flowers Have Sex, Leaves Eat Air, and Other Secrets of PlantsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Fish Don't Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of LifeVon EverandWhy Fish Don't Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of LifeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (699)

- Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit DisorderVon EverandLast Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit DisorderBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (283)

- Spoiled Rotten America: Outrages of Everyday LifeVon EverandSpoiled Rotten America: Outrages of Everyday LifeBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (19)

- The Hummingbirds' Gift: Wonder, Beauty, and Renewal on WingsVon EverandThe Hummingbirds' Gift: Wonder, Beauty, and Renewal on WingsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (60)

- The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist RuinsVon EverandThe Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist RuinsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (139)

- Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's GardenVon EverandSoil: The Story of a Black Mother's GardenBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (16)

- The Well-Gardened Mind: The Restorative Power of NatureVon EverandThe Well-Gardened Mind: The Restorative Power of NatureBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (3)

- When the Sahara Was Green: How Our Greatest Desert Came to BeVon EverandWhen the Sahara Was Green: How Our Greatest Desert Came to BeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (5)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsVon EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (1422)

- The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of ConsciousnessVon EverandThe Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of ConsciousnessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (251)