Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Collaborative Creativity

Hochgeladen von

cocoveinCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Collaborative Creativity

Hochgeladen von

cocoveinCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Collaborative Creativity

Daniel Gooch

University of Bath

Dept. of Computer Science

Bath

BA2 7AY

dg216@bath.ac.uk

Ryan Kelly

University of Bath

Dept. of Computer Science

Bath

BA2 7AY

rmk22@bath.ac.uk

Peter Lock

University of Bath

Dept. of Computer Science

Bath

BA2 7AY

pl218@bath.ac.uk

Jess Villanueva Perales

University of Bath

Dept. of Computer Science

Bath

BA2 7AY

jvp20@bath.ac.uk

No man is an island, entire of itself;

every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.

John Donne

Creativity is defined as the ability to produce

work that is novel, high in quality, and

appropriate (Sternberg et al., 2004, p. 351). They

view creativity as a wide-scoping topic that is

important at both individual and societal levels.

Simonton (cited by Sternberg et al., 2004, p. 358)

statistically links eminent levels of creativity in a

society to environmental variables that are sociodependent, such as war, availability of role

models, and number of competitors.

Vera John-Steiner is a professor of Linguistics

and Education at the University of New Mexico,

and author of Creative Collaboration (2000).

She sees a clear distinction between cooperation

and collaboration. In cooperative tasks

individuals make specific contributions and have

differing levels of involvement and intellectual

ownership of the resulting product. In

collaborative endeavors, there is a more fully

realised equality in roles and responsibilities and

participants frequently perceive their task as a

joint effort. This distinction is based on the work

of Damon & Phelps (1989).

The benefits of creativity are incredibly visible in

todays society. However, these creative products

are assumed by Sternberg et al. to be the

consequence of individual creativity. They make

no mention of the direct effect that a collection of

individuals can have on a single project. Rather,

the cognitive process of innovation is presented

as primarily the responsibility of the individual;

interaction between individuals in a creative work

is secondary, manifested in the form of criticism

or encouragement.

John-Steiner talks about the need for breaking

down the boundaries of the self. She quotes

Braque (cited by John-Steiner, 2000, p. 190) as

saying, We are inclined to efface our

personalities in order to find originality.

However, the degree of self-effacing and tentative

listening within a collaborative group can vary, as

can other traits such as relative individual

intellect and domain knowledge. John-Steiner

asserts a collection of distinct yet connected

patterns

of

collaboration:

distributed,

complementary, family and integrative.

Amongst others, we shall analyse primarily the

research of John-Steiner, Sawyer, Fischer and

Shneiderman in an attempt to reconcile an

understanding of collaborative creativity. We will

discuss the aspects of collaboration they consider

to be of importance, before looking at

environments they have developed to support

collaborative creativity. We will also evaluate a

selection of environments and consider their

respective successes and failures.

Distributed collaboration is the most flexible area

of collaboration and therefore the most fragile.

Individuals within a distributed collaborative

group exchange information, ideas and opinions.

However, their roles are informal and

voluntary. As an example, John-Steiner cites

-1-

electronic discussion groups, where one person

may assume a more active organizing role, while

others may remain lurkers. Distributed groups

are based around the task itself, so any major

disagreements may often lead to the dissolution

of the group. However, if deeper ties can be

established, such as respect, friendship or

comradeship, lasting partnerships can often form.

during the course of the work the emphasis of

Ariels role changed to both providing criticism

and suggesting content. It was at this stage that

Will decided to make Ariel co-author of the

series, writing that simple justice required that

the title page should bear both of our names.

John-Steiner concludes that the Durants moved

from being partners in dialogue who cooperated

with each other to full-fledged collaborators.

In complementary collaboration labour is divided

between group members based on the

complementary nature of their individual

expertise, disciplinary knowledge or personality

traits. This division of labour is fixed on

instantiation and remains the same whilst the task

is carried out. Therefore, relationships within the

group are defined by this labour-division, and so

there may be an implied (or indeed, explicit)

hierarchy within the group. It is only the shared

ownership of the final solution that will set the

collaborative group apart from a co-operative

group.

There is a degree of similarity between family

and complementary collaboration. However, the

latter only allows for fixed patterns of

collaboration, whereas the former allows for more

dynamic integration of expertise. The provision

of support structures within family collaboration

is essential: family collaborations without

sufficient support structures will soon break

down. John-Steiner writes that participants help

each other to shift roles, including the move from

novice to a more expert level.

John-Steiner argues that transformative changes

require joint efforts. The weight of disciplinary

and artistic socialization is hard to overcome

without assistance (John-Steiner, 2000, p. 203).

Her claim is that it is within the area of

integrative collaboration that the creation of new

paradigms and art forms is best facilitated. JohnSteiner states that integrative partnerships

require a prolonged period of vision,

concluding that integrative partnerships are

motivated by the desire to transform existing

knowledge, thought styles, or artistic approaches

into new visions.

As an example of complementarity in

collaboration, John-Steiner cites Albert Einsteins

development of the theory of general relativity,

where he enlisted the expertise of close friend

mathematician Marcel Grossmann to explain the

principles of Riemann geometry. Together they

co-authored two papers, and therefore their

endeavor is seen by John-Steiner as

complementarily collaborative, and not simply

cooperation between two domains.

Family collaboration is John-Steiners umbrella

term for collaboration between married or longterm sexual partners, or related individuals such

as siblings. Since the links between collaborators

in a familial context are deeper than the problem

they are addressing, there is a greater degree of

flexibility within the group in terms of roledefinition and responsibility. Trust is something

that is probably already existent to a high degree

between peers within the group or partnership.

John-Steiner uses the example of Cubism, created

and developed by Picasso and Braque in an

integrated, transformative collaboration (JohnSteiner, 2000, p. 203). Within this collaboration

there were no definitions of role; rather both

artists created their individual works, and sought

support, evaluation and fostering from the other.

The work of one of the pair was not thought to be

finished without the approval of the other.

Between them they encouraged one another to

make bolder moves into the newly-defined area

of cubism, a bold artistic movement in which the

subjects are represented simultaneously from

John-Steiner cites the collaboration between the

married couple Will and Ariel Durant, who

together wrote The Story of Civilization (JohnSteiner, 2000, pp. 11-15). Ariel began by simply

classifying the heaps of notes written by Will, but

-2-

different viewpoints using mainly basic shapes.

The confidence of their exploration is evident in

sequential art-pieces.

Sawyer believes that collaboration is the secret to

breakthrough creativity. By building on the work

of John-Steiner, he examines the spontaneous

improvisation of theatre groups and jazz bands,

where group success is often determined by each

participants ability to play off of other group

members. Each individual provides the sparks for

further creative innovations, resulting in an

entertaining performance. He believes that in both

improvisational groups and work teams, each

persons individual contribution provides the

spark for the next.

There is a need for a depth of relationship within

integrative collaborations akin to that within

family collaborations. John-Steiner notes the

overlapping of the boundaries of integrative and

complementary collaboration (John-Steiner,

2000, p. 70): it is the enormity of the task

undertaken by the collaborators, and arguably

whether the task is successfully completed, that

defines their group as integrative.

After examining the interactions of spontaneous

improvisational groups, Sawyer identified several

key characteristics of successful teams. These

include the ability to build on collaborators ideas

and allow innovation to emerge over time, the

practice of deep listening, the need to recognise

that innovation is inefficient (that not every idea

is a good one), that often surprising questions

emerge, and that innovation is bottom up and

therefore successful improvisational groups often

dont require a leader and can be allowed to selforganise and restructure as necessary.

Keith Sawyer, one of the worlds leading experts

on creativity, views creativity differently from

Vera John-Steiner in that he does not explicitly

state a difference between cooperation and

collaboration in creativity. This suggests that he

sees no distinction between the two. His overall

worldview

of

creativity

is

simplistic:

collaboration is absolutely essential for creativity.

Sawyer asserts that most people believe that

innovation occurs from the creative spark created

by one person. Sawyer contests that this simply

isnt the case; ideas emerge from a creative web

of individuals who all have some part to play in

the generation of the creative spark. Sawyer

describes how many innovations that are

considered to be the product of a single creative

mind are actually the results of collaboration

between seemingly unrelated individuals. For

example, in his book Group Genius (Sawyer,

2007, p. 78), he describes how the esteemed

authors J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis might

never have produced their renowned works of

fiction if they had not evaluated each others

ideas and collaborated with the members of their

Oxford University reading circle. Here we see an

example of the difference in definition of

collaboration by Sawyer and John-Steiner: the

latter would see Tolkien and Lewis as

cooperation partners, rather than collaborators.

Much of Sawyers work focuses on how

creativity

occurs

within

professional

multinational organisations. He believes that

successful companies keep small sparks of

creativity running by temporarily bringing

together individuals from across different

disciplines within an organisation, before taking

any innovations back with them to their

respective departments. He also believes that it is

important that companies separate their

innovation across a number of locations, in effect

raising a spatial boundary between the involved

parties. He cites Weicks claim that loosely

coupled organisations formed from autonomous

building blocks that can be brought together,

disconnected, or re-formed with relatively little

disturbance are more innovative than carefully

planned organisations (cited by Sawyer, 2007, p.

156).

Much of Sawyers work focuses on

improvisational groups. In Group Genius, Sawyer

explains how collaboration between individuals

can often unwittingly lead to the birth of new

insights and global phenomena. Furthermore,

Citing the work of Csikszentmihalyi (1996),

Sawyer describes the need for flow in

improvisational groups. Flow is the name given

-3-

to the state of mind experienced when a creative

individual is at his or her peak, such that they

experience a unified flowing from one moment

to the next, in which we feel in control of our

actions, and in which there is little distinction

between self and environment, between stimulus

and response, or between past, present, and

future (Sawyer, 2007, p. 42). Sawyer recognises

that for an environment to support collaboration,

it must support group flow.

to creativity. However, it seems that JohnSteiners breakdown of collaboration is different

to Fischers because John-Steiners is based on

the nature of interaction between members of a

group whereas Fischers is based upon each

members individual background knowledge.

Much of Gerhard Fischers work into creativity

focuses on the role of collaboration in design

activities. Fischer describes four barriers which

can affect the creativity of groups: Spatial,

Temporal, Conceptual and Technological

barriers.

There is some evidence to suggest that failures

play a role in collaborative creativity. Sawyer

(2007, pg. 109) offers a quote from Linus

Pauling: I am constantly asked by students how I

get good ideas. My answer is simple: First, have a

lot of ideas. Then, throw away the bad ones.

Likewise, Intels director of strategy and

technology, Mary Murphy-Hoye (cited by

LaBarre, 2002), states: If were not failing ten

times more than were succeeding, it means that

were not taking enough risks. This links with

the beliefs of Simonton (1996), who states that

the best bet for producing lasting ideas is to go

for a large quantity of ideas. These statements

correspond with the work of Schank & Neaman

(2001) who believe that In order to succeed, you

must fail. They provide an anecdote from

Michael Jordan who says: Ive failed over and

over and over again in my life and that is why I

succeed.

The Spatial barrier refers to the fact that group

members can be distributed across multiple

locations. This therefore means that participants

are unable to meet face-to-face. Fischer affirms

Brown and Duguids claim that digital

technologies

are

adept

at

maintaining

communities already formed. They are less good

at making them (Fischer, 2004). The main

opportunity is allowing the shift that shared

concerns rather than shared location becomes the

prominent defining feature of a group of people

interacting with each other (Fischer, 2004).

Sawyer observes that collaboration can occur

over time (Sawyer, 2007, p. 99). Fischer

recognises this, and identifies a temporal barrier

to collaboration. This barrier refers to the fact that

acquisition of knowledge takes a considerable

length of time, and design tasks are often realised

over a period of time and can involve many

different individuals. Furthermore, outside

individuals can often shed light on an old

problem, giving fresh insight and opinion which

can lead to the exploration of new creative

pathways.

This view that failure is integral to creativity

contrasts with John-Steiners view that during

distributed collaboration, failures can cause a

group to splinter and disintegrate. However,

sometimes groups are loosely coupled, whereas

an exceptional individual like Michael Jordan is

part of a strong team of basketball players, all of

whom will allow their star player some leeway

for failure.

Fischer believes that it takes a long time to gain

knowledge of a domain: to master as thoroughly

as possible what is already known in a domain

with the ultimate goal being to transcend

conventions, not to succumb to them. Fischer

mainly focuses upon the effect that long term

projects have upon groups. Even an individual

working on a project will change over time and

cannot be considered to have the same skill set at

all points in time.

Gerhard Fischers ideas of collaborative creativity

run in parallel with those of Sawyer. Fischers

manifesto is that The power of the unaided,

individual mind is highly overrated: The

Renaissance scholar no longer exists (Fischer,

2005, p. 128). Akin to John-Steiner and Sawyer,

Fischer believes that group processes are essential

-4-

According to Fischer, the main way of

overcoming the temporal barrier is to save the

rationale behind design decisions. Fischer

attempts to achieve two conflicting goals:

Recording design rationale should not subtract

too many cognitive resources from the task and

assure that rationale is partly formalised so that

computational support is easy to retrieve.

Fischer delineates collaborative groups into

Homogenous Design Communities also known

as Communities of Practice (CoPs) and

Heterogeneous Design Communities also

known as Communities of Interest (CoIs). CoPs

consist of practitioners who work as a

community in a certain domain undertaking

similar work (Fischer, 2004, p. 5). Examples

would include architects, urban planners or

traditional research groups. In comparison a CoI

brings together stakeholders from different CoPs

to solve a particular [design] problem of common

concern (Fischer, 2004, p. 5). An example of

this would be a team of software designers,

marketing

specialists,

psychologists

and

programmers interested in software development.

The Technological barrier is concerned with

making the computer a supporting tool rather than

a hindrance. This should lead to a relationship in

which computers do not emulate human

capabilities but complement them (Fischer,

2004). Fischer claims that design can be

described as a reflective conversation between

designers and the design they create. This is

termed to be back-talk. The main barriers

occur when the back-talk is represented in a

form that users are unable to comprehend or

when the back-talk created by the design situation

itself is insufficient. Domain Oriented Design

Environments (DODEs) attempt to resolve this

issue. The goals for DODEs in supporting

collaboration are to promote interaction with the

problem and not just the computer, and to

increase the back-talk of the situation by

integrating action and reflection into a single

environment.

CoPs are biased toward communicating with the

same people and taking advantage of a shared

background, whereas CoIs have greater potential

for creativity because different backgrounds and

perspectives lead to new insights. This is

supported by Sawyers claim that groups are

effective at generating innovation because they

bring together far more concepts and bodies of

knowledge than any one person can. He states

that group genius can only happen if the brains

in the team dont contain all the same stuff

(Sawyer, 2007, p. 72).

Fischers aim is not to categorise, but rather to

support groups by identifying useful patterns of

practice and helpful technologies. Whilst he

recognises that CoPs and CoIs can change over

time, he hasnt represented this in a formal way.

As Figure 2 demonstrates, the difference between

CoPs and CoIs could be viewed as a continuum

rather than a clear distinction.

Figure 2: the CoP-CoI continuum

Figure 1: A DODE example

-5-

Fischer et al. (2005) propose the use of boundary

objects to aid creativity. Boundary objects are

externalisations that serve to communicate and

coordinate the perspectives of various

constituencies. (Bruner, 1996) claims that

Externalisations produce a record of our mental

efforts, one that is outside us rather than in

memory. An example of a set of boundary

objects would be architectural designs including

blueprints through to prototypical mock-ups of

buildings used by architects, town planners and

clients. Boundary objects are important for two

reasons. Firstly, they serve as externalisations

which

can

then

undergo

innovative

manipulations, as discussed by Oxman (1997).

This is representative of a conversation between a

creator and his or her design (Schn, 1983). This

means that any technology that seeks to support

collaborative tasks must support the process of

externalising knowledge, such that it can then be

re-represented and redesigned.

Fischer has developed a number of tools to

support collaborative creativity. We will now

describe these tools and evaluate them against

both Fischers barriers (spatial, temporal,

technological and conceptual) and the criteria

identified from Sawyers work, namely

conversation, reflection, improvisation and

support of flow. As discussed previously,

evaluating how well a tool supports flow without

watching participants using the tool is impossible.

The final criteria for evaluation of the tools will

be whether the environment allows the user to fail

identified as important by Sawyer among

others.

Having identified the evaluation criteria, it is now

necessary to discuss the tools. Web2gether

(Fischer, 2004) is intended to provide

professional and social support for caregivers.

It is intended to not only allow people to find

resources, but also form social networks. This is

a good example of how to overcome both spatial

and temporal barriers because it brings together

participants from spatially disparate locations and

supports asynchronous communication. However,

we do not consider it an example of collaborative

creativity, rather merely a collaborative

information sharing tool; therefore, Web2gether

cannot be evaluated against our criteria.

The second reason boundary objects are

important is that they allow conversation to occur

between people involved in a design task, even if

those people have different knowledge bases.

Furthermore, Sawyer states that conversation

between people is critical to collaboration. The

spatial and temporal barriers identified by Fischer

may obstruct this conversational process. So, any

solution that attempts to overcome these barriers

must support conversation between the

individuals involved in a design task.

In order to evaluate Fischers work towards

developing collaborative environments, we would

like to use a number of criteria derived from the

work of Sawyer. We have identified a number of

important group processes that must be supported

in order to foster collaborative creativity. These

are the needs for conversation, reflection,

improvisation and the support of flow.

However, as flow is difficult to quantify

(especially without being able to observe

participants at work) it is impossible to

completely evaluate how well each environment

supports group flow.

Figure 3: Web2gether

-6-

The next example is called I-Balls, an application

that helps users to record and investigate design

rationale (Fischer, 2004). I-Balls is designed to

support projects that take place over an extended

period of time. The rationale behind decisions

[should] be recorded in the first place. In this

way the temporal barrier can be overcome

through recording key design decisions. It is also

intended to overcome the conceptual barrier as it

forms a barrier object which can support

communication about not only evolving artifacts

but also background context and rationale about

the artifacts. As the system allows you to

annotate the design in any way necessary it is

assumed that the system does allow you to fail as

an incorrect design can be annotated to describe

the reasoning behind the design. However this

being the case it suggests that the technological

barrier is not overcome as there is no back talk

from the design. Taking Sawyers criteria, the

system clearly allows conversation both with

the design and with the author. The system

supports reflection as the comments made upon

the design need not be statements but could be

questions to be answered after the reflection

period. The authors cannot tell whether the

system provides means for improvisation; on that

basis it is assumed that it does not.

important aspect of using physical objects is that

this allows the conceptual barrier to be overcome

as the boundary objects are clearly perceivable.

However, the spatial and temporal barriers are not

supported as the system requires face-to-face

interaction within a shared construction space.

The system does overcome the technological

barrier as the simulation produces back-talk

which is both sufficient and comprehendible. The

system does allow failure one example given in

(Arias et al., 2000) is planning bus routes. The

system is set up such that the users can construct

the route any way they like subsequently one of

the routes does not take into account any of the

population or business centres. The system

clearly allows conversation with the design.

However, given the co-located nature of the

participants, it is arguable whether the system

supports conversation between users. By

separating out the action space from the reflection

space the system makes a conscious effort to

support reflection. With regards to improvisation,

the system is based around simulations. It

therefore clearly allows users to improvise with

different ideas and test them out without fear of

that becoming the fixed design.

Figure 4: I-Balls

Figure 5: EDC

One of the more complex systems presented by

Fischer is EDC (Arias et al., 2000) (Fischer,

2004). It is intended to be used as a tool for

activities such as transportation planning or flood

mitigation. It consists of an action space whereby

simulations can be run and controlled using

physical objects, and a reflection space where

significant information is presented. The

One of the more controversial environments

Fischer has developed is CodeBroker. The system

monitors what a software developer is currently

doing and infers the problem they are trying to

solve. From this inference, the system delivers

reusable components (Fischer et al., 2005). The

system is only collaborative in as far as the

-7-

components are contributed from several

individuals. This essentially means that the spatial

and temporal barriers are not relevant. With

regards to the conceptual barrier, the code itself

stands as the boundary object. Technologically

the system encourages back-talk as the

component suggested is identified as being

relevant to the task the user is undertaking. Of

course it is questionable whether the system is

capable of performing such a task. If the match is

a trivial one the user can perform the match

themselves. Given the current state of AI research

it is unlikely that anything other than a trivial

match could be made. Likewise, it is questionable

as to whether such a system could allow you to

fail if the task is correctly identified and a

suitable component can be found, the only point

of failure is as to whether the task being

undertaken is the correct one. Likewise there is

no opportunity for improvisation or reflection as

the components are always relevant. Sawyers

only criteria that could be considered to be met is

that of conversation but only so far as the code

listing itself provides a conversation with the

problem.

certain domain (cited in Shneiderman, 1998b, p.

90). This new idea or pattern should also be

accepted by the field in order to be added to the

creative domain. Shneidermans overall aim is to

create a framework to boost the number of quality

creative innovations in all fields of knowledge.

Shneiderman proposes a framework called

Genex. This framework consists of four stages:

Collect: gather information from a certain

domain of knowledge.

Create: devising new ides using

appropriate tools to support creativity.

Consult: refine the idea with other fellows

and practitioners.

Disseminate: distribute that new creation

to the community.

According to Shneiderman, all these stages

should take place on a digital platform. This will

allow exploitation of standardization capabilities

to produce exchangeable data sets which can then

be processed by different applications and

distributed out into the community. Collecting

information is not traditionally seen as a

collaborative process. However, collaboration

from different sources is required to create a

common domain of knowledge. This domain of

knowledge can then be offered to all practitioners

and researchers as a starting point for their

studies. For example, summary chapters present

condensed knowledge, which are ideal starting

points for newcomers to a subject.

After retrieving information from the domain of

knowledge, the creative process starts.

Shneiderman claims that the creation of new

ideas should be an individual process supported

by computerised tools which enable the user to

achieve higher levels of creativity. However,

these new ideas should be refined by

collaborating with close colleagues or mentors.

This stage could also be carried out with the help

of computers. Researchers could post their work

to get reviews from other scientists. In addition,

Figure 6: CodeBroker

Ben Shneiderman does not provide an explicit

definition of collaboration or collaborative

creativity. However, he uses Csikszentmihalyi's

definition of creativity as the foundation for his

work. Csikszentmihalyi defined creativity as the

creation of new ideas or the realisation of an

unknown pattern using the elements found in a

-8-

e-mail, newsgroups and chat rooms could become

a means to collaborate with peers during the

refinement phase. This is a similar idea to

Fischers theoretical work on communities of

interest, where boundary objects are necessary to

overcome the conceptual barrier between diverse

participants.

In addition to proposing the Genex framework,

Shneiderman

also

took

part

in

the

development of some tools supporting his

framework. However, they can only be seen as

separate tools supporting certain phases of the

Genex framework, rather than a complete Genex

environment. The most successful tool is

Lifelines (Plaisant et al, 1996), an environment

for visualising and querying information about a

person or a set of persons throughout time.

Figure 7: LifeLines2

As well as LifeLines, Shneiderman has

participated in other minor projects, the main one

being Shore (Shore2000, 2008). The application

attempted to put in practice the third stage of the

Genex framework (Relate) by asking students

to post their work on a webpage to allow others to

review their work and to propose changes. This

environment was cited in Shneiderman's Genex

paper (Shneiderman, 1998), with the final version

titled `Shore2000. However, a different project

unrelated to Shneiderman has been carrying out

the same idea since 1991. It is called "arXiv"

(arXiv, 2008), and it is an e-Library of scientific

research papers managed by the Cornell

University Library. It holds more than half a

million of papers on Physics, Mathematics and

other sciences, and the number of papers is still

growing.

LifeLines tries to implement the first stage of

Genex ("Collect"), allowing the user to

retrieve information about personal records and

then display it in visual form. This visualisation is

done using a graphic representation of the record

as a set of actions occurring in a timeline.

According to the creators, this visualisation

technique allows the user to identify relationships

between different records that would be hard to

find using plain text. This tool was used to

display records of juvenile cases at the Maryland

Department of Juvenile Justice, receiving positive

feedback from users (Rose et al., 1996).

LifeLines was also used to display medical

records, although no particular feedback was

given by application users.

Although Shneiderman had no part in its

development, Scratch (Monroy-Hernandez, 2008)

can be seen as a Genex environment. This

environment is aimed at children and teenagers of

both sexes to learn, create and share

programmable media using a built-in integrated

development

environment.

Within

this

environment, users can look for previous work by

other users, download it, modify it and then share

it with the community of users to get feedback.

A second version of Lifelines (LifeLines2, 2008)

was released several years later. This version is

still in use (Wang, 2008) and is mainly applied to

the graphical representation of medical records.

The project keeps drawing the attention of the

community and several workshops have been

arranged to present improvements on the

application (June 2004 and May 2008).

-9-

Those works can also be used, if applicable, to

create new ones. This environment is probably

the best example of the Genex framework

because it gives the opportunity to carry out the

frameworks four stages:

Collect: users can search through a

database of more than 50,000 projects.

Create: new projects can be created via a

built-in tool.

Relate: users can ask for help from others.

Donate: once the project it is finished, it

can be distributed and be part of the

domain to be used as a starting point for

new projects or just as inspiration.

Shneidermans Genex framework does not

compare favorably with regards to the criteria

derived from Sawyer. Although it does support

some level of reflection and conversation with a

problem, it does not support synchronous

communication between participants in a task. It

also does little to foster improvisation in a

spontaneous group. Shneidermans relate stage

could support the production of analogies but no

mention of that is made during his work.

Shneiderman also makes no mention of the

barriers identified by Fischer.

Shneiderman initially seems unclear about the

structure of his Genex framework. In his original

work he proposes the need to relate, create and

donate (Shneiderman, 1998a). His view then

changes to the fact that you need to collect,

create, consult and disseminate (Shneiderman,

1998b).

He finally arrives at the need to collect, relate,

create, donate (Shneiderman, 2000) and only at

this stage does he explicate the reasons behind the

evolution of his model. Shneiderman claims that

the reason he altered his framework is because he

sought to combine both papers written in 1998,

citing the need to base his framework on the

close relationship [between] learning and

creativity (Shneiderman, 2000). He describes his

model as a semi-iterative process, whereby an

- 10 -

individual can return to a previous stage at any

time. At this point, his model is further confused

by the introduction of eight activities that can also

occur at any time during the Genex stages.

In 2000, Shneiderman contradicts himself when

criticising the view that problem solving in

creativity [is] portrayed as [the] lonely experience

of wrestling with the problem, breaking through

various blocks and finding clever solutions. This

directly contradicts his previous view that

creativity is a demanding personal journey that

follows diverse paths (Shneiderman, 1998b).

Any thought-process leading to this change of

opinion has not been made explicit in any of his

work.

Shneidermans own view of the creative process

has changed over time alongside his research.

Our main criticism is that he seems more

interested in using alliteration and clever rhymes

to create a snappy title for his manifesto instead

of doing anything that is substantial towards

creating environments that can support

collaboration.

There are many differences between the

researchers definitions and environments.

Fischer and Shneidermans views on the

collaborative process are wildly different: Fischer

sees collaboration as central to the creative

process whereas Shneiderman considers the

creative process to be a demanding personal

journey

that

follows

diverse

paths

(Shneiderman, 1998b).

There is a general acceptance that collaboration is

key to creativity. However, there is still

disagreement over the definition of collaboration

in creativity. Unlike Sawyer and Fischer, JohnSteiner makes a distinction between cooperation

and collaboration. Fischers view of collaboration

is that people must directly contribute to a task,

whereas Sawyer and Shneiderman consider any

kind of outside influence as collaboration. In

contrast, John-Steiner feels that joint ownership

of a group effort is a fundamental element of

collaboration.

Generally, the researchers have formed a strong

theoretical understanding of how to support

collaborative creativity, in terms of the processes

that need to be supported in order to optimise the

output of a creative group. However, their efforts

towards developing these environments have

been adequate but far from excellent. For

example, Fischers environments provide good

support for creative processes, overcome barriers

and allow participants to fail, but do not facilitate

support for these to occur at the same time. Thus,

there is potential for the research to be applied in

more effective forms to create successful tools.

Currently, the environments described in this

paper do not exist outside of the research

community. These tools will never succeed unless

they fit with existing practices or offer an

advantage over these practices that make change

worthwhile. The environments detailed in this

paper were only used by practitioners when they

were encouraged to do so. Once the research

ended, the use of the tools diminished.

With reference to Shneiderman, conceptually it is

still unclear what a Genex is capable of. Our

evaluation of Shneiderman is based upon our

vague idea of what a Genex is, which may or may

not correspond to Shneidermans understanding

of the model. Shneiderman states that Thesauri

are to words what Genexes will be to ideas

(Shneiderman, 1998b). The problem with this is

that words are well-defined and are easy to

collect because, in a language, there are a finite

number of words. Likewise, words have a fixed

interpretation, whereas ideas are transient.

Sawyer states that ideas must be left open to

multiple interpretations they should be

equivocal.

Creating a central store of knowledge is

problematic. Sawyer (Sawyer, 2007, p. 144)

describes how a number of professional

companies created databases trying to capture and

centralize the collective knowledge of their

professional staff. The goal was to inspire

innovation by helping people make connections,

but all of the firms discovered that these

databases were useless at facilitating innovation.

Sawyer states that databases are of little use with

- 11 -

problem-finding creativity and when no-one

knows what the problem is or what question to

ask, databases cant help (Sawyer, 2007, p. 145).

Secondly, computers cant tolerate indirectness.

Therefore, if a Genex is to be successful, it needs

to be able to suggest the question. The concept

of Genex seems to be more about creating

something that is good enough or best fit rather

than something that is truly creative.

Environments designed to support collaborative

creativity can only support the development of an

idea that already exists they cannot directly

suggest new ideas, but can sometimes help a user

discover new ones, as shown by Fischers ECD

environment.

We have argued that failure is critical to

developing creative ideas and any environment

that supports collaborative creativity must allow

for failures. This is because failing multiple times

assists the refinement of a creative solution and

failure helps you to see where you went wrong

and allows you to redefine your approach to a

problem.

John-Steiner

argues

that

the

collaborative team itself must be structured so

that failure does not cause the dissolution of the

group. Its not the act of failing that is important

but the acceptance of the failure and the ability to

reflect upon why the failure occurred. Therefore,

if an environment allows you to fail, it is also

supporting the redefinition of a question and

therefore the overall creative process.

John Donne said no man is an island, and

whilst the work of John-Steiner, Sawyer and

Fischer do not agree on a single definition of

collaborative creativity the acceptance of

collaboration as key to creative output is mutually

held.

There is still much work to be done towards the

development of environments that support

collaboration and collaborative creativity. If

collaboration is truly an integral part of creativity,

the need to develop environments that support

this process will only increase. The challenge lies

in building environments that effectively support

all of the processes necessary for collaborative

creativity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arias, E., Eden, H., Fischer, G., Gorman, A.,

Scharff, E. 2000. Transcending the individual

human mindcreating shared understanding

through collaborative design. ACM Trans.

Comput.-Hum. Interact. 7, 1 (Mar. 2000), 84-113.

arXiv. Available at: http://arxiv.org [Accessed:

28th November 2008]

Bruner, J., 1996. The Culture of Education,

Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Burleson, W. 2005. Developing creativity,

motivation, and self-actualization with learning

systems. International Journal of HumanComputer Studies, Volume 63, Issues 4-5,

October 2005, Pages 436-451.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1996. Creativity: Flow and

the Psychology of Discovery and Invention.

HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY.

Damon, W., Phelps, E. 1989. Critical distinctions

among three approaches to peer education.

International Journal of Educational Review, 5 8

(2), 9-19.

Fischer, G., 1994. 'Domain-Oriented Design

Environments,' Automated Software Engineering,

1(2), pp. 177--203.

Fischer, G. 1999. Symmetry of ignorance, social

creativity, and meta-design. In Proceedings of the

3rd Conference on Creativity & Cognition

(Loughborough, United Kingdom, October 11 13, 1999). C&C '99. ACM, New York, NY, 116123.

- 12 -

Fischer, G. 2004. Social creativity: turning

barriers into opportunities for collaborative

design. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference

on Participatory Design: Artful integration:

interweaving Media, Materials and Practices Volume 1 (Toronto, Ontario, Canada, July 27 31, 2004). PDC 04. ACM, New York, NY, 152161.

Fischer, G. 2005. Distances and diversity: sources

for social creativity. In Proceedings of the 5th

Conference on Creativity &Amp; Cognition

(London, United Kingdom, April 12 - 15, 2005).

C&C '05. ACM, New York, NY, 128-136.

Fischer, G., Giaccardi, E., Eden, H., Sugimoto,

M., & Ye, Y., 2005. 'Beyond Binary Choices:

Integrating Individual and Social Creativity,'

International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies (IJHCS) Special Issue on Creativity (eds:

Linda Candy and Ernest Edmond), p. (in press).

Fischer, G., Nakakoji K., Ostwald J., Stahl G.,

Sumner, T., 1998. Embedding critics in design

environments, Readings in intelligent user

interfaces, Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.,

San Francisco, CA.

John-Steiner, V. 2000. Creative Collaboration,

Oxford University Press, Oxford.

LaBarre, P. 2002. Interview with Robert Sutton.

Fresh Start 2002: Weird Ideas That Work, Fast

Company, January, 2002, 68.

LifeLines2.http://www.cs.umd.edu/hcil/lifelines2.

[Accessed: 28th November 2008]

Monroy-Hernndez, A., Resnick, M., 2008.

Empowering Kids to Create and Share

Programmable Media. Interactions (March +

April, 2008). pp. 50-53.

Oxman, R., 1997. Design by Re-Representation:

A Model of Visual Reasoning in Design, Design

Studies 18, 4, 329--347.

Plaisant, C., Milash, B., Rose, A., Widoff, S.,

Shneiderman,

B.,

1996.

LifeLines:

Visualizing Personal Histories. In: CHI 96.

Vancouver, BC Canada. Publisher, Place?

Rose, A., Plaisant, C., Shneiderman, B., Norman,

K., Vanniamparampil, A., Milash, B., Slaughter,

Laura., 1996. User Interfaces for Juvenile Justice

Information

Systems.

Available

at:

http://www.cs.umd.edu/hcil/youth-services/.

[Accessed: 28th November 2008]

Sawyer, R. K., 2007. Group Genius: The

Creative Power of Collaboration, Basic Books,

New York, NY.

Schank R., Neaman, A., 2001. In: Forbus K.,

Feltovich, P. (Eds), Motivation and Failure in

Educational Systems Design, Smart Machines in

Education. AAAI Press/ MIT Pres, Cambridge,

MA.

Schn, D. A., 1983. The Reflective Practitioner:

How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books,

New York USA.

Shneiderman, B., 1998a. Relate - Create Donate: A teaching/learning philosophy for the

cyber-generation. Computation in Education, 31,

1, 25 - 39.

Shneiderman, B., 1998b. Codex, memex, genex:

The pursuit of transformational technologies.

International Journal of Human Computer

Interaction, 10. 2, 87-106.

- 13 -

Shneiderman, B., 2000. Creating creativity: user

interfaces for supporting innovation. ACM

Transactions on Computer Human Interaction,

7, 1, (March 2000), 112-138.

Shneiderman, B., 2002. Leonardo's Laptop:

Human Needs and the New Computing

Technologies, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Shore2000.Available at:

http://www.otal.umd.edu/SHORE2000

[Accessed: 28th November 2008]

Simonton, D. K., 1996. Creative expertise: A lifespan developmental perspective. In K. A.

Ericsson (Ed.), The road to excellence (pp. 227

253). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Sternberg, R. J., Lubart, T., Kaufman, J. C., &

Pretz, J. E., 2005. Creativity. In: The Cambridge

Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning. Holyoak

K., Morrison, R,

Eds., UK: Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press, pp 351-369.

Wang, T.D., Plaisant, C., Quinn, A.J., Stanchak,

R., Shneiderman, B., 2008. Aligning Temporal

Data by Sentinel Events: Discovering Patterns in

Electronic Health Records. In: Proceedings of the

twenty-sixth annual SIGCHI conference on

Human factors in computing systems (Florence,

Italy). ACM, New York, NY, USA: pp. 457-466.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Intro 2007 Wielecki ENGDokument2 SeitenIntro 2007 Wielecki ENGcocoveinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender and Social Relations in New Music - Tackling The Octopus - SEISMOGRAFDokument15 SeitenGender and Social Relations in New Music - Tackling The Octopus - SEISMOGRAFcocoveinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction Defining The New Cultural History of Music Its Origins Methodologies and Lines of InquiryDokument1 SeiteIntroduction Defining The New Cultural History of Music Its Origins Methodologies and Lines of InquirycocoveinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ranciere Hatred of Democracy PDFDokument55 SeitenRanciere Hatred of Democracy PDFcocoveinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adorno Aesthetic TheoryDokument7 SeitenAdorno Aesthetic TheorycocoveinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urban Stud 2005 Quinn 927 43Dokument18 SeitenUrban Stud 2005 Quinn 927 43cocoveinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Lab Manual No 13Dokument3 SeitenLab Manual No 13Hammad JawadNoch keine Bewertungen

- NB! This Price List Applies To Service Agreements, That Are Concluded With Nordea Bank AB Latvia BranchDokument34 SeitenNB! This Price List Applies To Service Agreements, That Are Concluded With Nordea Bank AB Latvia Branchwaraxe23Noch keine Bewertungen

- 6400t Rev-BDokument4 Seiten6400t Rev-BGloria HamiltonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experience The Latest & Safest in Building Circuit ProtectionDokument28 SeitenExperience The Latest & Safest in Building Circuit ProtectionYashwanth KrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ef3602 9Dokument2 SeitenEf3602 9AwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To R: Shanti.S.Chauhan, PH.D Business Studies ShuatsDokument53 SeitenIntroduction To R: Shanti.S.Chauhan, PH.D Business Studies ShuatsShanti Swaroop ChauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mason Melito: EducationDokument2 SeitenMason Melito: Educationapi-568517799Noch keine Bewertungen

- GE Proficy Machine Edition Getting StartedDokument124 SeitenGE Proficy Machine Edition Getting StartedIrfan AshrafNoch keine Bewertungen

- 27U RackDokument6 Seiten27U Racknitin lagejuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Etap - Relay CoordinationDokument311 SeitenEtap - Relay CoordinationManohar Potnuru100% (1)

- MclogitDokument19 SeitenMclogitkyotopinheiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arco Solar Inc.: Case Analysis OnDokument12 SeitenArco Solar Inc.: Case Analysis OnAnish RajNoch keine Bewertungen

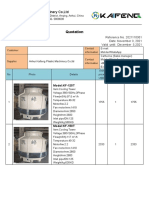

- KAIFENG Quotation For 150T Cooling TowerDokument13 SeitenKAIFENG Quotation For 150T Cooling TowerEslam A. FahmyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banumathy.D Updated Profile 1Dokument7 SeitenBanumathy.D Updated Profile 1engineeringwatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Detail 02 Eave Gutter With Protruding Roof Detail 01-A Ridge Detail Saddle RoofDokument1 SeiteDetail 02 Eave Gutter With Protruding Roof Detail 01-A Ridge Detail Saddle Roofmin miniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biochemical Oxygen DemandDokument18 SeitenBiochemical Oxygen DemandUnputdownable Bishwarup100% (1)

- Nvidia CompanyDokument4 SeitenNvidia CompanyaaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1743 LKWActrosXXXXXX 954frDokument4 Seiten1743 LKWActrosXXXXXX 954frgeothermal3102100% (1)

- System Failure AnalysisDokument9 SeitenSystem Failure AnalysisHermance Yosepf Setiarto Harimurti50% (2)

- Technology and Culture - ReadingDokument3 SeitenTechnology and Culture - ReadingBraulio Pezantes100% (1)

- PR-1078 - Hydrogen Sulphide Management ProcedureDokument22 SeitenPR-1078 - Hydrogen Sulphide Management Procedureromedic360% (1)

- Fi SlingDokument4 SeitenFi SlingSony TogatoropNoch keine Bewertungen

- PC210-240-7K M Ueam001704 PC210 PC230 PC240-7K 0310 PDFDokument363 SeitenPC210-240-7K M Ueam001704 PC210 PC230 PC240-7K 0310 PDFCarlos Israel Gomez100% (10)

- Etk 001 en de PDFDokument740 SeitenEtk 001 en de PDFBinh le Thanh0% (1)

- D8 9M-2012PVDokument16 SeitenD8 9M-2012PVvishesh dharaiya0% (4)

- 381Dokument8 Seiten381Nidya Wardah JuhanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HVAC Water TreatmentDokument7 SeitenHVAC Water TreatmentDuxToyNoch keine Bewertungen

- TDS 9-11SA Mechanical TroubleshootingDokument34 SeitenTDS 9-11SA Mechanical Troubleshootingahmed.kareem.khanjerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revised Runway Length Discussion (20171206) - 201712211212022318Dokument3 SeitenRevised Runway Length Discussion (20171206) - 201712211212022318Ilham RaffiNoch keine Bewertungen

- BK Report and ProjectDokument55 SeitenBK Report and ProjecttesfuNoch keine Bewertungen