Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

New Changes in Organizational Design To Instigate Co-Creation Dynamics and Innovation: A Model Based On Online Multiplayer Games

Hochgeladen von

Lucas RoldanOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

New Changes in Organizational Design To Instigate Co-Creation Dynamics and Innovation: A Model Based On Online Multiplayer Games

Hochgeladen von

Lucas RoldanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

New Changes in Organizational Design to Instigate Co-creation Dynamics and

Innovation: A Model Based on Online Multiplayer Games

M. Panizzon1, L. B. Roldan1, M. A. Menegotto1, E. C. H. Dorion2

1

Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul/Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Porto Alegre/Caxias do Sul, Brazil

mpanizzo@ucs.br; lucas.roldan@pucrs.br; margamenegotto@hotmail.com; echdorion@gmail.com

a hub model that integrates and connects communities,

including the possibility of creating economic value. The basic

premise of a multiplayer game is that it allows multiple

players to participate (synchronously or asynchronously) in

the same game. Furthermore, this model currently

demonstrates its potential in generating profits. A report

produced by Digi-Capital on the current size of the global

gaming market, shows that mergers and acquisitions in this

sector produced for $ US $ 4 billion in 2012, while 38% were

generated by multiplayer games companies.

Since any economy extends itself up to a companys level,

it can be compared and observed that in several online

multiplayer games, the transactions of buying and selling to

occur in various environments, where the product created by

the players fit with the market value. Furthermore, a

multiplayer game provides its own evolution as a social

organization, where the players continually promote

improvements, customizations and changes to their rules of

operation from its combination of knowledge and interaction

with each other. Consequently, a multiplayer online game

constitutes an organization in constant change. A multiplayer

game has a different development scheme than an individual

game play style. Jos Pablo Zagal [1], in the late twentieth

century, brought this reflection for the first time and promoted

the following research problem What should be considered

when designing a multiplayer game? At the time of the

article, if multiplayer games were scarce, as discussed by the

authors, the definition of multiplayer today is set as a decisive

aspect in a game format, with a characteristic responsible for

its perpetuity or not. In fact, any multiplayer feature triggers a

series of dimensions that change the dynamics of the operation

of the game, and at the same time, can be a source of

innovation for organizations, when the online multiplayer

games models are confronted with the design of the

organizations.

This paper explores how the principles of electronic

multiplayer games can become an important mechanism for

dynamic co-creation and innovation for the organizations. To

establish a line of reasoning, a series of theories of

organizational design models, business networks and design of

online multiplayer games will be developed. Therefore, the

research question is which dimensions emerge due to the

feature of online multiplayer games and what elements

could alter the dynamics of organization-customer

relationship in a co-creation process?

It is understood that there is an ongoing research in the

studies related to the Internet, as a part of the co-creation

process, which has been explored and developed; however, in

the field of games, its is a research gap and it is still

considered as unexplored and incipient. In a paradigm shift,

the internet could be perceived as a platform for customer

engagement in product innovation in a process of co-creation

[2,3]. However, since such a platform allows an active

participation, either through emotional involvement or product

design, it still would not offer the same level of participation

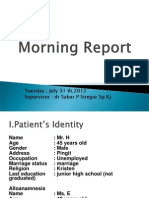

Abstract This theoretical article proposes a Closed Cycle

Model of Online Dynamic Co-Creation (ODCC). Its an open

innovation model based on the principles of online multiplayer

games development for organizations in Business to Client (B2C)

context, as an alternative to promote Dynamic Online Cocreation and Innovation. Online multiplayer games have the

propriety to evoke dimensions that combine knowledge creation,

sense-making, loyalty, sense of community, interaction and

emotion, which are essential for continuous and dynamic process

of co-creation. This model opens the possibility that from the

moment the players community in a virtual environment, linked

to the organization, becomes a strategic asset for co-creation and

innovation, the games industry can serve as a new paradigm for

organizational design, going beyond purely entertainment.

Keywordsco-creation, open innovation, multiplayer games,

organizational modeling, strategy

I.

INTRODUCTION

This theoretical article proposes an open innovation model

based on the principles of online multiplayer games

development for organizations that implement Business to

Client (B2C), as an alternative to promote Dynamic Online

Co-creation and Innovation. In support of these arguments, a

contextualization and development on the theoretical field of

electronic games are developed with the purpose of

establishing a interface with the field of organization's design

and the mechanisms of co-creation.

In a period from classic games of the 80s to the

multiplayer phenomenon of the beginning of the XXI century,

electronic games have evolved significantly over the past 30

years, as well as their insight into organizations and the

business models in the field of games. A study from the

Global Games Market Report (2013) shows that the

projections of the game design market in 2016 will be U.S$ 86

billion. From this perspective, there is a thriving field for

research and development. In this context, the evolution of

electronic game design does not only present a technological

point of view, through the improvement of their graphic

elements for example, but gets into a deeper level of

understanding, in terms of conception design of a game,

particularly in terms of the level of interaction with the user

and between users. In this sense, the in-depth study of the

principles governing the new electronic games can contribute

to identify the elements that can generate a brand new

reflection on the functioning of organizations, specifically

when it comes to the elements of co-creation and innovation.

In essence, electronic games were initially conceived and

developed to have an individual player. They were designed

for a single individual to interact with the game. However,

with the advent of the Internet, the category of multiplayer

online games caused a massive structural change in the field,

where games were developed to be a simple script platform

programmed to generate temporary entertainment, to become

978-1-4799-5529-9/14/$31.00 2014 IEEE

467

Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE ICMIT

that a multiplayer game provides. These elements are

important to generate motivation, to engage and to maintain a

longer lasting, cyclic and dynamic co-creation process. For

example, the case of World of Warcraft shows that two

specific economic features emerge from this environment:

firstly, through the process of co-creation, where the original

content is produced by a gamer with its intellectual property

and, secondly, where the interaction of creation does not only

take place before the launch of the product (game), but still

continues after its release, in the form of continuous

interaction [4]. Then, such motivation and behavior are

important to be analyzed, since it affects the ability of cocreation [5].

However, the process of co-creation, which lies in a

dimension of product development, cannot be dissociated

from the organizational dimension, taking into perspective

aspects of models, strategies and processes. Partly, because

user interaction in the games industry can improve firm

performance (organization, business model) [6,7]. In that

context, what needs to be considered as organizational design

is an issue that was sought to be answered in different ways

for more than 70 years from the theories of administration. In

a more endogenous and mechanized perspective of the

organization per se, both the organic approaches for

enterprise networks and the principles in the field of

organizational design have evolved over time. These changes

are being driven by transformations in the dynamics, and the

conditions set up by the external environment of the

organizations: competition, cooperation, coopetition and cocreation. Therefore, it is relevant to investigate these elements,

since they affect organizational design and its capacity for

creativity and co-creation.

This paper is divided into three sections: the first part

elaborates on the aspects of the traditional organizational

design; the second refers to the network approach, and the

third brings a discussion on game design. Each approach

constitutes an element of the final model.

II.

common requirements of different organizations in different

states. The authors also believe that the organizational

structure is used to handle two types of relationships: (1) the

liability, which is responsible for what, and (2) the authority,

who reports to whom. Such a structure is conventionally

represented by a tree in which two-dimensional boxes

represent the responsibilities and hierarchy, and the lines

represent the flow of authority.

Cooperation between companies has aroused great interest

in the academic and the business community, through growing

increase in strategic alliances [12]. In this context, emerge the

concept of virtual organization, which represents an

association of independent organizations (partners), has

appeared strongly to share resources and skills, and to achieve

common goals such as exploring an opportunity [13]. There

are four principles that govern the design of the virtual

organization. The first is to create boundaries around a

temporary organization with external partners, where the

organization can look like a separate entity, in a joint venture.

The second refers to the use of technology to connect people,

goods and ideas. More too often, virtual organization is not

palpable in terms of separate offices, facilities and other

infrastructure, as it only exists in people's minds. The third

proposes that each partner brings its domain of excellence to

support the new form of structure; and the fourth one points

out the importance to seize opportunities and dissolve the

partnership when needed, absorbing the provided learning

[13].

The virtual organization offers to companies the ability to

move swiftly to exploit a favorable market opportunity. As

they are collaborative, it involves having skills in order to

generate new opportunities and profits, but also to share risks

and losses [14]. Virtual design also allows a company to

provide an extension of a product that would be impossible

otherwise and also jointly leverage organizational assets that

are distributed among the partners. Another virtual advantage

is the manner that an organization can be easily dissolved or

absorbed as the opportunity for collaboration disappears [14].

Virtual organizations are used to exploit a market opportunity

through partnerships with complementary organizations. This

happens because usually an organization does not have all the

necessary skills to meet the particular need of a market, so it

needs to find partners to reach their objectives (these could

even be competitors). Consequently, a virtual organization is a

strategic mechanism that generates temporary partnerships,

enabling the combination of knowledge, technology

appropriation, and flexibility. Therefore, its fundamental to

the process of co-creation, and mostly in the multiplayer game

context. It can be dissolved when necessary, without losing the

base knowledge that was built. Once the interactions occur

through digital means, records of communications are in

explicit knowledge. In this sense, the format of a virtual

organization becomes potentially suitable as a basis of cocreation environment. However, the type of interaction that

should occur in this environment is what will be discussed in

the following section, since a virtual organization can be

modeled in terms of competition or cooperation and

coopetition.

MODELING COMPETITION

The first studies dealing with organizational design aim at

modeling organization to competition. More turbulent are the

environments in which organizations are embedded, more

stability they seek. However, those organizations generally fail

to realize that their only equilibrium in a turbulent

environment is their dynamism. Consequently, in turbulent

environments, institutions and companies require to be able,

ready and willing to adapt themselves [8]. For the companies

actually competing in this market, it is essential that they have

established a more organic structure; proposing more than just

an organizational structure, but a complex pattern of

interactions and coordination that link technology, the tasks

and the human components of the organizations, to ensure that

they achieve their objectives. Part of the reflection of this

paper is to understand organizational design as a way to

facilitate the flow of information within the organization and

to integrate it in order to reduce uncertainty in decision

making [9].

More frequently, the organizations need to co-evolve in

changing environments; facing uncertainty and seeking

innovation through new forms of partnership [10,11].

However, the organizations are complex and dynamic

nonlinear systems that do not grow in a steady and predictable

manner. For the authors, organizational design is part of a

social architecture that is constituted by a set of drawings that

can be used to build a real structure, which constitutes a

representation of an idea that may constitutes a valid base for

III.

MODELING COOPERATION AND COOPETITION

After the analysis of the organizational design field linked

to competition, the concepts of networks with a focus on

cooperation and coopetition are introduced. In an economic

perspective, networks constitute organizational forms that are

ranging from a complete hierarchical integration to a total

individuality in the market [15]. Bringing the term

468

Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE ICMIT

"networking" in a social context, it can be defined as "a set of

actors who have been lasting relationships with repeated

exchanges one another and, at the same time, with no

legitimate organizational authority to arbitrate and resolve

disputes that may arise during the exchange "[16]. This

definition suggests that an organizational network has

longstanding relationships between the actors and the absence

of established authority to regulate these relations. Any

network structures that have such logic of their own, with

unique advantages, reach levels of integrity that cannot be

achieved in a dichotomous relationship of market-hierarchy

[16].

However, since both economist and sociologist are known

as correct, they studied, even so, only part of the subjects [17].

For the authors, networks can acquire both organizational

forms. The differences in structure and purpose first raise

partial hierarchy-market characteristics, such as joint ventures,

which can be guided in structural coordination mechanisms,

using contracts to avoid any kind of opportunism. On the other

hand, some networks may be based on social links, where the

actors do not consider opportunism as a determinant and seek

trust, reciprocity and mutual help as a basis for their relations.

The concept of networks of companies relates that they are

long-term purposeful arrangements among distinct, but

related individual profitable businesses, that allow each firm to

gain or sustain competitive advantages over their competitors

outside the network [18]. In an attempt to provide a better

understanding of the diversity of types of networks, was

developed a framework [19] called conceptual orientation

map, which indicates the main dimensions of networks and

how they are structured. The authors introduce, on a vertical

axis, the nature of the relationship between the network

participants [20]. The relations can either be established by

cooperation or hierarchy. Cooperation relations are generally

practiced by businesses of micro, small and medium size,

configuring networks of horizontal cooperation. The

conceptual model introduces a horizontal axis, which

represents the level of formalization in the existing network.

The relationships between the actors within a network can be

configured by a level of informal interaction, without the

existence of rights and duty's contracts such as alliances, or by

a level of formal relationships, established through contractual

documents, which regulate the relationship between the parties

in the business networks.

In an environment of increasingly dynamic business,

companies are realizing the importance of collaborating with

clients to create and sustain competitive advantages.

Collaboration with partners and even competitors has become

a strategic imperative for companies worldwide in business

networks [21], [22], [23]. Recently, scholars who study

marketing and strategy have focused on the collaborations that

occur with clients to co-create value [24], [25]. While

collaboration with clients can span multiple business

processes, one of the most important is collaborative value

creation through product innovation. In concordance of the

results of the authors, [26] address the involvement of actors

in networks, treating them as possible sources of collaborative

innovation. They indicate that the distinctive capabilities of

the fastest means of communication, such as the Internet,

serve as a platform for customer engagement, including

interactivity, greater range, endurance, speed and flexibility.

They also suggest that companies can use these resources to

engage with customers in product innovation through

collaborative mechanisms based on communication processes.

The same authors discuss on how these mechanisms may

facilitate the generation of collaborative innovation at

distinctive stages of product development (back end vs. front-

end steps) process and to different levels of customer

engagement through a sociological view of knowledge cocreation and sharing. However, with the emergence of the

phenomenon of innovation, and mostly of open innovation,

mechanisms that establish bonds of co-creation may turn out

to be decisive for new types of organizations. In this sense, are

there elements in the field of multiplayer games design that

could influence the design of organizations, through a view of

co-creation and innovation? How these principles have

adherence with the mechanisms of virtual organization and

cooperation through networking?

IV. CO-CREATION AND DESIGN OF MULTIPLAYER GAMES

First, it must be understood what consists in the design of a

game. The designer of a game is a visionary who plays such

game even before it was invented [27]. From this perspective,

a game designer can be seen as an entrepreneur who has an

idea and seeks to express it through the development of this

project.

The beginning of the development process of a game is

very similar to the process of developing a business plan. Just

as a game designer develops the concept paper, which regards

to the objectives and the context of the game, the entrepreneur

seeks from a market analysis to define his business model. The

context can derive from a research just to create an attractive

environment for the game. Afterwards, is developed the

structure of the game and its operational scheme, where in a

simplified manner, are found three basic elements [28]: i)

players, ii) rules and goals and iii) props and tools. The players

are the users who interact with the existing mechanisms and

tools in a game, to achieve certain objectives, conditioned to

rules. For every single game, there will be players, objectives

and defined rules; and a set of mechanisms and tools that

allow all players to achieve their goals in the specific game.

However, multiplayer game ads on new elements to its basic

model that promote the evolution of the game and the creation

of economic value, not just making an isolated computer

program.

In terms of game evolution, for the purpose of this study, it

was defined as the changes that occur over time, including its

rules and goals, and its mechanisms and tools, from its first

release. In summary, any game or any organization that

experiences a set of innovations is mainly due to the

interaction between the players.

In non multiplayer game, the program has no change with

regard to the dimensions of the rules and goals, and the props

and tools. The player must follow the rules of the game, trying

to achieve its goals. Thus, there is no co-creation involved, as

well as no interaction with other agents. However, in a

multiplayer game, modifications can occur in the rules of the

game (to improve the balance between the players, for

example), the creation of new features (stimulating player

interest and fidelity), which demonstrates the evolutionary

characteristic of a multiplayer game. In summary, there are six

new dimensions [28] that incorporate this type of game, as

shown in table 1:

TABLE I

DIMENSIONS OF A MULTIPLAYER GAME [28]

469

Dimension

Description

Social

interaction

It consists in the interaction and the communication between individuals who

are involved in the game. In a multiplayer game, this interaction can be

spontaneous or stimulated to enhance development during the game. The social

interaction is the dimension that makes the interface between the players, the

rules, the goals and tools, but still, this dimension is structural. In that sense,

Zhong [45] have assessed the influence that games like Massive Multiplayer

Online Role Play Gaming, have on social capital (online and offline) and

collective participation. Hsiao and Chou [46] have studied how this kind of

game influences on player loyalty in a virtual community.

Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE ICMIT

Dimension

Competition

and

Cooperation

Synchronicity

or

asynchronicity

Coordenation

Prop/Tool

dependance

Meta-gaming

which is also used by [31] to understand the operation of a

game. The Activity Theory is a concept that represents a

framework to understand human activity [32, 33]. The authors

suggest that human activity is mediated by auxiliary stimuli

that may be in the form of signs or tools. The model

emphasizes the inherent social interactions of human activity,

where the activities cannot be treated separately from

collective relations concepts, regardless of the conditions and

the ways in which they are developed. In such pattern, the

activity is a collective and systemic unity that is driven by an

object, which is considered as the main driving force activity.

It is perceived from the Activity Theory, as a model that

explains human activity, which elements such as rules and

tools are involved. The model incorporates two important

aspects regarding co-creation, in respect to the motivation and

sense-making of the value of creation. These two dimensions

affect individual issues, since co-creation is highly dependent

on these stimuli.

Still, this concept of Co-Creation is exploited by [34], who

analyze the concept of co-creation in terms of two dimensions:

the level of openness of the process (anyone can attend or if

there is a selection process) and property (level contribution).

In essence, once a client may openly contribute to the process,

community configurations can be observed. For [35], the

issues concerning the level of client participation related to the

level of organizational design are most critical to the

development of co-creation. The co-creation process in games

was also studied by [36], where the author concluded that the

level of customization, content, interactivity and

complementarily influence more quickly the level of

acceptance of the players (consumers with product

knowledge) and are still associated with their self-esteem. The

author believes this process, through interaction and cocreation ability to customize content, awakens a pleasant and

effective interaction between the players and the system

within these virtual communities.

These elements are aligned with the dimensions of the

Activity Theory and the Multiplayer Game Design model

(which involves the dimensions of sense-making, motivation,

interaction). Mainly, it must take into account that the games

promote interaction between players, offering mechanisms of

interdependence, which promotes experiences, fun and flow

[37]. For the authors, there are two important mechanisms that

stimulate a game; the task and the interdependence reward.

Conducting an experiment comparing the effects of low and

high task interdependence and of high and low reward

interdependence on three variables (fun, flow and

performance); the authors arrive at the following conclusion:

In a low interdependence task context, players experience

more fun, have higher levels of flow and realize better

performance when a low interdependence reward system is

obtained. In contrast, in a high interdependence task, all of

these means are larger and a high interdependence of reward

condition is also obtained. It also implies that in a behavioral

perspective, there is linearity in relation to fun when a taskreward is offered. These dimensions corroborate with the

proposal of [38], who analyzed online communities as sources

of innovation. They observed the phenomenon of frustration

and reaction, trying to analyze the triggers of positive and

negative behavior in a co-creation community. The authors

point out that positive or negative satisfaction at the results;

the perceived sense of community and justice are important

determinants to trigger co-creation in this type of environment,

and still involving the dimension of task-reward.

Finally, it was also observed in a survey that assessed the

effects of perceived security and fun in multiplayer games and

their influence on attitude and loyalty [38]. Still, these

Description

Depending on the rules and the goals of a game, competition or cooperation

among members of a team (community) may be necessary for its development.

This dimension is directly linked to the players and the rules of the game. In

fact, since many multiplayer games focus on competition, is through

cooperation between its players whom many of the objectives (quests or

missions) can be developed.

This dimension works with the time synchronicity factor, where a requirement

that all players be active at the same time to have the game to run. In a

synchronous game, all players must participate at the same moment, with rules

and penalties. In asynchronous games, there is the possibility of independence

among the players on the game platform. This dimension is linked directly to

the game rules, as well as their tools.

When the multiplayer question emerges, the coordination and capacity to

control its process becomes necessary to ensure the synchronicity required for

the game to develop.

This dimension refers to the level of technology (tools) needed for the game to

get underway. For example, a multiplayer game (like a game of paintball) that

does not require computers have low dependence prop, while a game that

requires a computer has a high level of dependence on technology.

It occurs due to the asymmetry of information between the players, and

consists in games that arise and occur in parallel, inserted into the main game.

This dimension relates to the rules and goals of the game and the players.

Based on these dimensions, the authors [28] propose a

model for the development of multiplayer games, presented in

figure 1, which shows the difference between a game

developed on the basic perspectives (players, rules and tools),

and the ones developed under a multiplayer perspective.

Apparent differences arise, primarily during the establishment

of the mechanisms that generate these dimensions; through the

conditions of co-creation of the game environment itself,

which may generate innovation, through social interaction and

collaboration. The players promote changes in the rules and

goals of the game, and even the tools in its possession as

players, and many times, such innovations may occur due to

meta-gaming, which are the focus of discussion and parallel to

the main game script.

Fig. 1. Model to design a multiplayer game [28]

It is important to mention that there are three main

perspectives in game development [29]. At the beginning,

games had a more behavioral focus with direct controls. It

secondly moved to a constructivist focus, characterized by a

socio-cultural context, beyond the constructivist perspective. It

is from this new generation of meaning, interaction and

culture that are provided enabling environments for cocreation and innovation. In this context, the issue of games as

platforms for open innovation are being exploited by [30], as

open innovation is considered as a shared activity which

involves social interaction, synchronicity and coordination

mechanisms, as well as the meta-type gaming events (not

directly related to core business), environments that appear

within the game, such as events that promote interactions to

promote open innovation.

Another theoretical approach that converges with the

Multiplayer Games Model Design is the Activity Theory,

470

Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE ICMIT

perspectives are aligned to the work of [26], which indicates

that the communities established in turbulent environments

need to observe an economic value generation, to supply the

initial stimulus and establish a positive and continuous cycle

of knowledge creation or co-creation. In this context, the

dimension of enjoyment and reward need to be associated. To

conclude, it can be understood that the development process of

a game is very similar to the process of developing a business

plan. It can merely propose an attractive environment for a

game, or market, or limit itself to either the processes or the

behavior that makes the whole context an evolutionary pattern.

Each pattern can either be of competition, cooperation or

coopetition. However, its understand comes through e relevant

and clear model to read.

V.

combine. The virtual ambient promoted by an online game can

provide these mechanisms.

Furthermore, it can be considered that, the environment of

the online multiplayer game, through its characteristics, has

the possibility to promote some dimensions (in a consumer or

creator perspective). These dimensions were findings from

previous gaming research. Therefore, the analysis uses these

conclusions in the Co-Creation context Model, as showed in

figure 4 and it can be observed the benefits of this new

approach. In this perspective of analysis, a new set of

questions about how de interaction between organizations and

customers emerge. How do customers become part of a

multiplayer online game company? Could a person have his

own avatar connected to games of various organizations

(organizations or networks) actively participating in the cocreation of their products? And how it would bring new

possibilities in terms of co-creation, given the fact that these

interactions trigger motivations, attribution of meaning,

aggregated value, behavior and interactions, combinations of

capabilities and access to stakeholders (through coalition

parties)?

TABLE II

THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL PROPOSED

Based on the elements identified in the previous sections,

it is observed that they all converge with two specific

structuring dimensions: strategic and behavioral. The strategic

dimension is related to organization, and the behavioral

dimension is related to the individual. The model presented in

figure 2 supports the co-creation concept has a set of

encounter process between the organization and the customer.

The organization plan, design and measure experiences and

opportunities to co-create. The customer participates in this

relationship experience in a manner that triggers your

behavior, and this can be done using emotion.

That is an important link with the proposed new model of

Dynamic Online Co-creation. The previous research showed

that games, especially multiplayer, can evoke a set of

dimensions, which mediate this relationship experience due to

the elements like task and reward, in a context of fun. The

games are mechanisms that can generate emotions, since they

deal with stories, archetypes, challenges, characters and

interactions. So, the multiplayer online game serves has an

encounter process between the customer and the organization.

DIMENSIONS OF MULTIPLAYER GAMES [28]

Dimension

Interaction and

open Innovation

[30]

sense-making and

motivation [31]

customization,

interactivity and

self-esteem [36]

task, fun and

reward [37]

Outcome

perception;

perceived justice

and sense of

community [38]

Access,

motivation, Value

and Capability to

Combine [40, 41,

42, 43]

Social capital and

Loyalty [39, 45,

46]

Contribution to dynamic and long term co-creation relationship

A multiplayer online game enhances the number of interaction, therefore,

enhances the number of ideas in an open innovation perspective. This kind

of game as a channel of idea's input, can promote not online a quantitative

enhancement, but also qualitative, due to the interaction between players

who serves as a source of diversity of and new ideas, in a context of

challenge and history.

These interactions occur in a context of challenge and history provided by

the game. The game isnt just a task, but can be modeled to be something

grater and with a long term timing, that somehow maintains the motivation

of the player (and therefore, his contribution in the co-creation process), in a

most effective way that just in a single campaign.

The possibility in multiplayer games of customization provides an important

mechanism for co-creation. When you provide the possibility to the player

to combine different types of alternatives (for example, the creation of a

personalized car), this enhances the interactivity and therefore, the

motivation to stay in the game, and also the self-esteem, because the

personalization in a game is a form of exteriorization of your inner self.

Some co-creation experiences use the task and reward approach. And

multiplayer uses the task and reward in a progressive way and in a fun

context. Therefore, the motivation can be sustained for long term,

especially because the game has the possibility to create new chapters,

quests, stories that maintain the produced knowledge of the player and puts

in a new and innovative context.

This approaches points that perceived justice in the game, and the

possibility to realize the outcome is an important element to sustain the

player in the community. Being part of a co-creation relationship, where the

player can see something in the game become a real product or an

incremental innovation of a product, can be an important mechanism to a

long-term relationship in this game..

The co-creation is, in essence, a combination of knowledge. A virtual layer,

or an online game, is a platform that makes possible for the act of accessing

new knowledges and the capabilities to combine in a manner that creates

value. As a player, the knowledge created can be more available than other

initiatives of co-creation, sustaining therefore, a long-term relationship.

Previous research concluded that multiplayer games can enhance social

capital (thrust) and therefore, loyalty, and this attributes are fundamentals to

sustain a long-term co-creation relationship.

Hence, the argument that is proposed in this study about

what changes would be necessary in the current organizational

design to promote co-creation and innovation is the

establishment of a virtual layer (virtual organization),

connected between the company and its customers, but not

simply a static layer, like a blog or a single game. An online

multiplayer game that evokes that dimensions observed in

literature has the possibility to sustain a co-creation process

more dynamic and long term.

Advances in organization design take place from a new

perspective when analyzed in a B2C perspective. In a business

to business (B2B) perspective, a higher level of interaction is

expected once all interested parties have their supply

contracts. However, in relation with the consumer, the

dynamics of attraction becomes different since distinct stimuli

are required to motivate and co-create. An online game could

only be used for brand awareness or unilateral customer

interaction purposes. However, an online multiplayer game is

Fig. 2. Co-Creation Model [44]

Therefore, the proposed conceptual model is based upon

the concepts bounded by the online multiplayer game model,

as a virtual layer of interaction between the company (or a

network of companies) and the client, through a virtual

community of creation, which embed the Transaction Cost

Theory, the Complexity theory, Management and the

Organization Community and Intellectual Property theories,

according [13,26]. Also, due to the nature of a co-creation,

which is, in essence, a new knowledge, is observed in the

literature that the generation of knowledge requires some

mechanisms [40, 41, 42, 43], like: a) access of the interested

parts to combine knowledge; b) possibility to see the value for

this combination; c) motivation to combine; d) capabilities to

471

Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE ICMIT

not just a promotion tool for brand awareness. A multiplayer

online game sets the stage for what is called a dynamic on-line

co-creation or co-creation in a closed cycle. An important part

of this mechanism is that, as participation and interaction on

the platform manage customer co-creation, the value

generated by their innovations return into the community. This

cycle creates individual and collective incentives for the

activity of co-creation, and enables the generation of economic

value from cooperation or coopetition between communities

of customers / players who interact in this environment.

The model proposed, the Closed Cycle Online DynamicCo-creation are shown in Figure 3 enhances the prospect of

[44] about co-creation, establishing the multiplayer online

game as a layer of virtual organization that mediates between

corporate networks and customer community. It is based in the

model proposed in Figure 2, which set a base for co-creation

(encounter process between customer and business),

aggregating the multiplayer elements presented in Figure 1

(bases of game: players, rules and goals, props and tools in the

context of multiplayer) which evokes the dimensions

presented in Table II. This is adherent with the relationship

experience, in terms of emotion, cognition and behavior of this

customer network. However, the closed cycle concept are set

in terms of value return for the client due his effort to cocreate. This model also expands the perspective on the model

in Figure 2: another change are due to the perspective of

cooperation. An online multiplayer game can be a virtual layer

of co-creation for a network of companies, and not just for a

single company. Through it, the combination of knowledge is

held and triggered by devices that enable these types of games

(sense-making, fun, task motivation), as noted by the authors.

changes to the products, since it has access to a whole

combination of knowledge (context/sense-making), could it

result in co-creation and innovation? Considering the effects

of social capital and loyalty that can be seen in games, could

this platform not be a new mechanism for retaining customers

from their involvement in the ongoing stories? The issue is

that products do have different life cycles, and these are

related to distinct types of co-creation, as exposed in Figure 4

[46].

In this sense, the process of co-creation should follow the

life cycle of the product, not just as an isolated moment (as

characterized most co-creations), to come to meet such

alignment. Therefore, industry games can plan multiplayer

games with a wide story, associated to achievements, temporal

marks and other gaming strategies to try to maintain the

collaboration of the player in the different stages of the timecycle. Normally, a process of co-creation is mostly used to the

starting point, a campaign like a contest to capture new ideas.

The sustain strategy pattern proposed here is to achieve this

via a closed-cycle in an on-line dynamic co-creation. After all,

the perceived outcome (value returned from business to the

client), is an important element to sustain the relationship, and

the customer relationship database.

This new perspective broadens discussions in terms of

contract needs and design, for example. Under such new

dynamic, could customers not become part of an organization

or even its shareholders? From the moment that the player is

continuously accessing the environment, performing some

kind of research and development, and being able to receive

real value for it, how would it affects on organizational

dynamics itself?

Fig. 4. Co-creation versus Life-Cycle [46]

Therefore, this paper aims to propose a model of dynamic

online co-creation, specifically for B2C business patterns,

from the implementation of a multiplayer game as a virtual

layer of interaction between a company (company networks)

and its customers. From the literature survey, it was identified

a potential for the application of this model, since it stimulates

essential dimensions for the establishment of co-creation and

value creation for the customer. This dimensions are expressed

in term of sense-making, motivation, interactivity, self-esteem,

task, fun, reward, outcome perception, social capital and

loyalty. In summary, on one hand, it is expressed as the active

multiplayer aspects of the game, such as motivation and

Sense-making; the friendly access to the game, its proper

capacity or output; and its ability to promote open innovation.

On the other hand, it incentivizes social capital and loyalty

through interactivity, fun and reward, as well as the perception

of outcome and sense of community. All these aspects are

essential to the process of co-creation, and this are an

important advancement in the theory and mechanisms of cocreation, and sustain the novelty of this model.

Fig. 3. The Conceptual Model of Closed Cycle Online Dynamic Co-Creation

This proposed platform, as a new layer in organizational

design, goes beyond a simple social network model (since

these networks do not incorporate storytelling/history

mechanisms, characters, motivation, tasks that arouse games);

it becomes a strategy pattern of a company to attract and

retain customers in a dynamic virtual environment, stimulating

co-creation and also generating economic value. Being a

virtual platform, this layer could serve medium-size

companies to small business networks. Also, the model

promotes the proprieties to the customer network to: a) access

of the interested parts to combine knowledge; b) possibility to

see the value for this combination; c) motivation to combine;

d) capabilities to combine.

Take, for example, any company producing surfboards,

skateboards, or even an automaker. As a massively

multiplayer online game, where clients are actively involved

in stories related to these context, tasks, interactions, get

involved and get entertained, discuss, amend and promote

472

Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE ICMIT

However, future research on the refinement of the

framework suggests, in view of the limitation of this study,

that the mechanisms of co-creation tend to have a different

behavior. For example, an automotive company that seeks to

implement an online multiplayer game as a co-creation

platform will require a distinct narrative scheme than a

smartphone or clothing company. Nevertheless, the purpose of

seeking meaning for co-creation via interaction, fun and

possible combination of knowledge for innovation are

common and fundamental elements, regardless of the business

sector.

Thus, this model of virtual organization extends theory in

the co-creation field, proposing the interaction among

networks of companies and customers (cooperation

dimension) through the virtual organizational layer: a

multiplayer game, which will continuously and dynamically

establish a new social organization and shall generate

economic value from the co-creation and innovation. In this

perspective, a discussion on competitive advantage emerges,

due the moment that the database of a virtual enterprise

environment becomes a strategic asset for co-creation and

innovation.

Therefore, this paper seeks to provide a new understanding

about the games industry. In this model, its role goes beyond

pure entertainment, since the multiplayer games must be

designed associated with an organizational environment

(integrating workflows and routines), through an attractive and

interesting scheme that retains market players in consumer's

environments, vying for time and attention, to promote

dynamic online co-creation of new products. As a future

research, this model provides a new perspective to extend the

range of operations from the gaming industry to converge with

open innovation models, which are sources of competitive

advantage for organizations. This article, hence, contributes

towards the development of this framework, presented in

Figure 3 whose purpose is to integrate the process of cocreation and dynamic on-line in a new form of organizational

design, establishing a virtual layer of multiplayer game to

interact (emotional dimensions evoked), as the process of

relationship between company and client. Based in this

framework, we suggest future case studies or experiments to

validate statistically the co-creation outputs and relationship

degree in an on-line multiplayer game environment directly

associated with an organization. This discussion goes even

further and proposes a discussion about a research agenda, in

the organizational, behavioral and technological dimensions to

achieve the implementation of this model in organizations or

network of organizations.

Lastly, the paper contributes to advances in organizational

design theory and co-creation theory, since this is a

contemporary discussion, provoked nowadays in 2014 by

[47]: whats new about news form of organizing?

REFERENCES

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

[25]

[26]

[27]

[28]

J. P Zagal, M. Nussbaum and R. Rosas. A model to suport the design of

multiplayer games, Presence, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 448-462, 2000.

M. Sawhney, G. Verona and E. Prandelli. Collaborating to create: the

internet as a plataform for customer engagement in product innovation,

Journal of Interactive Marketing, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 4-17, 2005.

L. B. Jeppsen and M. Molin. Consumers as co-developers: learning and

innovation outside the firm, Journal: Technology Analysis & Strategic

Management, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 363-383, 2003.

M. Davidovici-Nora. The dynamic of co-creation in the video game

industry: the case of world of warcraft. Communication & Strategies,

no. 73, pp. 43-67, 2009.

V. Bilgram, A. Brem and K. Voigt. User-centric innovation in new

product development systematic identification of lead users harnessing

[29]

[30]

[31]

[32]

473

interactive and collaborative online-tools, International Journal of

Innovation Management, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 419-458, 2008.

P. LLerena, T. Burger-Helmchen and P. Cohendet. Divison of labor and

division of knowledge: a case study of innovation in the video game

industry. Schumpeterian Perspectives on Innovation, Competition and

Growth. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 315-33, 2009.

R. L. Ackoff. Towards flexible organizations: a multidimensional

design, Omega, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 649-662, 1997.

N. Anand and R. L Daft. What is the right organization design. Working

paper series. Unplublished. December 7, 2006.

A. De Toni, G. Biotto and C. Battistella. Organizational design drivers

to enable emergent creativity in web-based communities, Learning

Organization, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 335-349, 2012.

R. Duncan. What is the right organization structure? Decision tree

analysis provides the answer, Organizational Dynamics, vol. 7, no. 3,

pp. 59-80, 1979.

V. Eiriz. Proposta de tipologia sobre alianas estratgicas, Revista de

Administrao Contepornea, vol. 5, n. 2, pp. 65-90, 2001.

H. Afsarmnesh and L. Camarinha-Matos. A framework for management

of virtual organization breeding environments. Collaborative Networks

and Their Breeding Environments. Springer US, pp. 35-48, 2005.

H. Afsarmanesh, L. Carminha-Matos, S. Msanjila. On management of

2nd generation Virtual Organizations Breeding Environments, Annual

Reviews in Control, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 209-219, 2009.

O. Williamson. Markets and Hierarchies: Analsysis and antitrust

implications. New York. The Free Press. pp. 303, 1985

J. M. Podolny; K. L Page. Networks forms of organization, Annual

Review of Sociology, vol. 24, pp. 57-76, 1998.

M. Baldi; F. Lopes. Rede forma hbrida ou nova forma?, Revista

Portuguesa e Brasileira de Gesto, vol. 1, n. 3, 2002.

J. Jarillo. On strategic networks, Strategic Management Journal, vol.

9, no. 1, pp. 31-41, 1988.

M. Marcon and M. Moinet. La stratgie-rseau: ensai de stratgie. Paris:

ditions Zro heure., pp. 235, 2000.

A. Balestrin. A dinmica da complementaridade de conhecimentos no

contexto das redes interorganizacionais. Ph.D. dissertation,

Administration, Univ. Fed. Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2005.

B. Nalebuff and A. Branderburger. "Co-opetition: Competitive and

cooperative business strategies for the digital economy", Strategy &

Leadership, vol. 25, no.6, pp. 28 35, 1997.

R. Gulatti, N. Norhia and A. Zahere. Strategic Networks, Strategic

Management Journal, vol. 21, no. pp. 203-215, 2000.

M. Iansiti and R. Levine. Strategy as ecology, Harvard Business

Review,pp.1-11, march, 2004.

C.K. Prahalad and V. Ramaswamy. Co-creation experiences: the new

practice in value creation, Journal of Interactive Marketing, vol 18, no.

3, pp. 5-14, 2004.

S. H, Thomke and E. Von Hippel. Customers as innovators: a new way

to create value, Harvard Business Review, vol. 80, no. 4, pp. 74-81,

2002.

M. Sawhney and E. Prandelli. Communities of creation: managing

distributed innovation in turbulent markets, California Management

Review, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 24-54, 2000.

R. Pedersen. Game design foundations. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

pp.309, 2009.

J. P Zagal, M. Nussbaum and R. Rosas. A model to suport the design of

multiplayer games, Presence, vol. 9, no. 5, pp., 448-462, 2000.

S. Egenfeldt-Nielsen. Beyond Edutainment: Exploring the Educational

Potential of Computer Games. IT University of Copenhagen,

Department of Innovation, 2005.

G. Vardaxoglu and E. Baraolou. Developling a plataform for serious

gaming: open innovation throught closed innovation. Procedia

Computer Science. vol. 15, pp. 111-121, 2012.

D. Lazarou. Using cultural-historical activity theory to design and

evaluate an educational game in science education, Journal of

Computer Assisted Learning, vol. 27, no.5, pp. 424-439, 2011.

L.S. Vygotsky. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher

Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, ,

pp. 159, 1978.

Y. Engestrom. 1987. Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical

Approach to Developmental Research. Orienta-Konsultit, Helsinki, pp.

368, 1987.

Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE ICMIT

[33] M. Pater The 5 guiding principles of co-creation, Fronteer Strategy,

Amsterdam, white paper, unpublished, 2009.

[34] L. Pluijin. Realizing co-creation. Master thesis, Strategic Management,

Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Tilburg University.

2010.

[35] S. Yeh. Involving consummers in product design throught

collaboration: the case of online role-playing games. Cyberpsychology

Behavior and Social Networking, vol. 13, no 6., pp. 2010.

[36] B. Choi, I. Lee, D. Choi and J. Kim. Collaborate and share: an

experimental study of the effects of task and reward interdependencies

in online games, Cyberpsychology & Behavior, vol. 10, no 4., pp. 2007.

[37] J. Gebauer, J. Fuller and R. Pezzei. The dark and the bright side of cocreation: Triggers of member behavior in online innovation

communities. Journal of Business Research, vol. 66, no. 9, pp. 15161527, 2013.

[38] D. Shin. The dynamic user activities in massive multiplayer online

role-playing games, International Journal of Human-Computer

Interaction, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 317-344, 2010.

[39] J. Nahapiet and S. Ghoshal. Social capital, intellectual capital and the

Organizational advantage, The Academy of Management Review, vol.

23, no 2, pp. 242-266, 1998.

[40] W. Cohen, D, Levinthal. Aborptive capacity: a new perspective on

learning and innovation, Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 35, pp.

128-152, 1990.

[41] B. Kogut, U. Zander. Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities

and the replication of technology, Organization Science, vol. 3, no. 3,

pp. 383-397, 1990.

[42] R. Grant. Towards a knowledge-based view of the firm, Strategic

Management Journal, vol. 17, winter special issue, pp. 109-122, 1997.

[43] A. Payne, K. Storbacka and P. Frow. Managing the co-creation of

value, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. vol. 36, no.1, pp.

83-96, 2008.

[44] Z. Zhong. The effects of collective MMORPG (Massively multiplayer

online role-playing games) play on gamers online and offline social

capital. Computers in Human Behaviour, vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 23522363,

2011.

[45] C. Hsiao and J. Chiou. The effect of social capital on community

loyalty in a virtual community: Test of a tripartite-process model,

Decision Support Systems, vol 54, no. 1, pp. 750 757, 2012.

[46] A. Orcik, Z. Tekic, Z. Anisic. Customer Co-creation throughout the

producct life cycle. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and

Management, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 43-49, 2013.

[47] O.Alexy and M.Reitig. Whats new about new forms of organizing?.

Academy of Management Review, vol. 39, no2, pp.126,180, 2014.

474

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Teachers Guide Full Version Lowres PDFDokument78 SeitenTeachers Guide Full Version Lowres PDFAdel San Agustin50% (2)

- Erik Hjerpe Volvo Car Group PDFDokument14 SeitenErik Hjerpe Volvo Car Group PDFKashaf AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effects of Wearing Make Up On The Confidence Level of The Students at ATEC Technological College AutoRecoveredDokument19 SeitenThe Effects of Wearing Make Up On The Confidence Level of The Students at ATEC Technological College AutoRecoveredSey ViNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Change in OrganizationDokument18 SeitenCultural Change in OrganizationSainaath JandhhyaalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 17, CaballeroDokument8 SeitenModule 17, CaballeroRanjo M NovasilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speech About EducationDokument1 SeiteSpeech About Educationmarvin dayvid pascua100% (1)

- 1 Da-1Dokument19 Seiten1 Da-1Ayesha khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Education Inequality Part 2: The Forgotten Heroes, The Poor HeroesDokument1 SeiteEducation Inequality Part 2: The Forgotten Heroes, The Poor HeroesZulham MahasinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consultant List PuneDokument4 SeitenConsultant List PuneEr Mayur PatilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper Ideas About MoviesDokument4 SeitenResearch Paper Ideas About Moviesfkqdnlbkf100% (1)

- Growing Spiritually: How To Exegete 1 Peter 2:1-3?Dokument61 SeitenGrowing Spiritually: How To Exegete 1 Peter 2:1-3?PaulCJBurgessNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Minute English Learning EnglishDokument5 Seiten6 Minute English Learning EnglishZazaTevzadzeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grading Rubric For A Research Paper-Any Discipline: Introduction/ ThesisDokument2 SeitenGrading Rubric For A Research Paper-Any Discipline: Introduction/ ThesisJaddie LorzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Standards of Learning Plan Format Virginia Teachers For TomorrowDokument4 SeitenStandards of Learning Plan Format Virginia Teachers For Tomorrowapi-3188678690% (1)

- Item Unit Cost Total Cost Peso Mark Up Selling Price Per ServingDokument1 SeiteItem Unit Cost Total Cost Peso Mark Up Selling Price Per ServingKathleen A. PascualNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5.3 Critical Path Method (CPM) and Program Evaluation & Review Technique (Pert)Dokument6 Seiten5.3 Critical Path Method (CPM) and Program Evaluation & Review Technique (Pert)Charles VeranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Npad PGP2017-19Dokument3 SeitenNpad PGP2017-19Nikhil BhattNoch keine Bewertungen

- Love - On Paranoid and Reparative ReadingDokument8 SeitenLove - On Paranoid and Reparative ReadingInkblotJoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociolinguistics Christine Mallinson Subject: Sociolinguistics Online Publication Date: Nov 2015Dokument3 SeitenSociolinguistics Christine Mallinson Subject: Sociolinguistics Online Publication Date: Nov 2015Krish RaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuesday, July 31 TH, 2012 Supervisor: DR Sabar P Siregar SP - KJDokument44 SeitenTuesday, July 31 TH, 2012 Supervisor: DR Sabar P Siregar SP - KJChristophorus RaymondNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vit Standard 1 Evidence 1Dokument3 SeitenVit Standard 1 Evidence 1api-222524940Noch keine Bewertungen

- Analytical Exposition Sample in Learning EnglishDokument1 SeiteAnalytical Exposition Sample in Learning EnglishindahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palme EinsteinDokument21 SeitenPalme EinsteinVantur VictorNoch keine Bewertungen

- 99999Dokument18 Seiten99999Joseph BaldomarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Helpling A Depressed Friend or Loved OneDokument1 SeiteHelpling A Depressed Friend or Loved OneCharles CilliersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem Solving and Creativity Faci 5Dokument34 SeitenProblem Solving and Creativity Faci 5Tevoj Oinoleb100% (5)

- Customer Service Orientation For Nursing: Presented by Zakaria, SE, MMDokument37 SeitenCustomer Service Orientation For Nursing: Presented by Zakaria, SE, MMzakariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research 1Dokument33 SeitenResearch 1Margaret GalangNoch keine Bewertungen

- AEF3 - Part of WorksheetDokument1 SeiteAEF3 - Part of WorksheetReza EsfandiariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nys StandardsDokument3 SeitenNys Standardsapi-218854185Noch keine Bewertungen