Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning Experiences For Secondary School Learners: The Zimbabwean Case

Hochgeladen von

IOSRjournalOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning Experiences For Secondary School Learners: The Zimbabwean Case

Hochgeladen von

IOSRjournalCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME)

e-ISSN: 23207388,p-ISSN: 2320737X Volume 5, Issue 3 Ver. III (May - Jun. 2015), PP 96-102

www.iosrjournals.org

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning

Experiences for Secondary School Learners:

The Zimbabwean Case

Anna Gudyanga1; Ephias Gudyanga1

1

Midlands State University, Faculty of Education,

Department of Educational Foundations, Management and Curriculum Studies

Bag 9055, Gweru, Zimbabwe

Abstract: Teacher preparation emphasizes application of foundational issues anchored in psychological,

sociological and philosophical underpinnings. With such knowledge, teachers are expected to effectively

organise the learning experiences of children accordingly. This study, therefore, sought to find out to what

extend in-service teachers were able to organise learning experiences that are developmentally appropriate.

The mixed methods approach guided this study, as it was informed by both the positivist and interpretivist

paradigms which acted as lenses through which we viewed this study. Questionnaires, interviews and class

observations were the methods used as data collecting tools. Twenty participants (13 females, 7 males), were

purposively selected from Gweru urban secondary schools of Zimbabwe. It was noted that teachers are not able

to implement Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) for various reasons ranging from heavy teaching

loads, big classes, low teaching motivation, inadequate DAP knowledge among others. In the midst of other

recommendations, it was highlighted that parents were to meaningfully interact with schools to bridge the gap

between the home and the school, notwithstanding challenges facing the teacher which require the urgency

which cannot be gainsaid.

Keywords: Age, culture, curriculum, environment, experience, teaching.

I.

Introduction

As experienced educators, we noted that teachers have challenges, in synchronising theory with

practice. This is a cause for concern. Parents, communities and learners expect teachers to effectively utilise

developmentally appropriate teaching practices. Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) describes an

approach to education that guides educators in their everyday practice, giving them information from which

decisions based on their knowledge of child development can be made. [1] advocate that DAP considers:

Age appropriateness: what is best for most children of a particular age?

Individual appropriateness: what is best for a specific child's development?

Culturally and social context appropriateness: what is most relevant and respectful of a child and the child's

family, neighbourhood and community.

Developmentally appropriate learning experiences relate to organised learning that recognises the

physical and cognitive developmental milestones of learners as suggested by different psychologists. Based on

theories of Dewey, Vygotsky, Piaget, Bruner and Erikson, DAP reflects on interactive, constructivists view of

learning [2-3]. Key to this approach is the principle that the child constructs his or her own knowledge through

interactions with the social and physical environments.

The major objective of teacher preparation in Zimbabwe (both pre- and in service) is to educate

teachers so that they graduate with relevant skills, which enable them to organise developmentally appropriate

learning experiences. This study therefore seeks to find out to what extent in-served teachers are able to organise

learning experiences that are developmentally appropriate?

II.

The Context And Justification

Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) is both a psychological and a curriculum issue and hence

there is no way we can tackle the topic before the terms psychology and curriculum are defined. Psychology is

basically a study of human mind and behaviour whereas ccurriculum is the totality of learning experiences

provided to students so that they can attain general skills and knowledge at a variety of learning sites [4].

Curriculum is therefore a programme of planned experiences and as a result of those experiences, the child

acquires different forms of skills. Consequently, curriculum is the whole of interacting forces of the total

environment provided for pupils' experiences in that environment. In light of this, both psychological and

sociological issues, albeit philosophical to some extent, all become subsets of, and foundationals of curriculum.

DOI: 10.9790/7388-053396102

www.iosrjournals.org

96 | Page

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning Experiences For Secondary...

Building on this argument, curriculum becomes the sequence of potential experiences set up in the school for

the purposes of disciplining children and youth in ways of thinking and acting.

[5] defines curriculum as a selection from the culture of a society. Zimbabwe is a multicultural society.

Learning should be relevant to the children's lives outside the classroom. Students should be able to fit into the

society from which they come from and not to be outcasts. Learning experiences become developmentally

appropriate if informed by the people's culture since child developmental knowledge is embedded in a sociocultural context. Children's educational successes require congruence between what is being taught in the school

and the values expressed in the home. Parents in homes are children's first teachers and have a life-long

influence on their childrens values, attitudes and aspiration [6]. If learning is to be meaningful to individual

children, teachers must create a culturally responsive and relevant learning environment. [7] also asserts that

increasing the continuity and congruence between children's home experiences and school environment is

particularly critical to the success of children from diverse cultures and social classes.

Developmentally appropriate practice is teaching that is attuned to childrens ages, experiences,

abilities, and interests, and that helps them attain challenging and achievable goals [8]. Teaching in a

developmentally appropriate way brings together and meeting the learner where he or she is and helping

children achieve goals. Teachers keep the curriculums learning goals in mind as they determine where children

are and the next steps forward. What is challenging and achievable varies from one child to the other, depending

on each childs level of development; prior experiences, knowledge, and skills; and the context within which the

learning takes place. To be developmentally appropriate, teaching practices must be effectivethey must

contribute to the childrens on-going development and learning. That is, if children are not learning and

progressing toward important outcomes, then the practices and experiences in the program are not

developmentally appropriate. To ensure that their practices are in fact effective and developmentally

appropriate, teachers need to be intentional in everything they do [9].

[10] identifies three fundamental considerations that guide teachers in making decisions about what is

developmentally appropriate for children. Teachers are to:

1. Consider what is known about development and learning of children within a given age range. Having

knowledge of age-related human characteristics allows teachers to make general predictions within an age

range about what materials, interactions, and experiences will be safe, interesting, challenging, and within

reach for children, and thus likely to best promote their learning and development. This dimension is

sometimes called age appropriateness.

2. Consider what is known about each child as an individual. Gathering information about the strengths,

interests, and needs of each individual child in the group enables practitioners to adapt and be responsive to

that individual variation.

3. Consider what is known about the social and cultural contexts in which children live. Learning about the

values, expectations, and behavioural and linguistic conventions that shape childrens lives at home and in

their communities allows teachers to create learning environments and experiences that are meaningful,

relevant, and respectful for all children and their families.

All learning and development occur in and are influenced by social and cultural contexts [11]. In fact,

appropriate behaviour is always culturally defined. The cultural contexts a child grows up in begin with the

family and extend to include the cultural group or groups with which the family identifies. Culture refers to the

behaviours, values, and beliefs that a group shares and passes on from one generation to the next. Because

children share their cultural context with members of their group, cultural differences are differences between

groups rather than individual differences. Therefore, cultural variations as well as individual variations need to

be considered in deciding what is developmentally appropriate. Children learn the values, beliefs, expectations,

and habitual patterns of behaviour of the social and cultural contexts in their lives. Cultures, for example, have

characteristic ways of showing respect; there may be different rules for how to properly greet an older or

younger person, a friend, or stranger. Attitudes about time and personal space vary among cultures, as do the

ways to take care of a baby and dress for different occasions. In fact, most of our experiences are filtered

through the lenses of our cultural groups. We typically learn cultural rules very early and very deeply, so they

become part of our conscious thought. Social contexts of young childrens lives differ in ways such as these: Is

the child growing up in a large family, or a family of one or two children or in a single-parent family, a two

parent family, with same-sex parents, or a household that includes extended family members, in an urban,

suburban, or rural setting? Has the child been in a group care settings from a young age, or is this the first time

in a group program? What social and economic resources are available to the family? All of these situations

frame the social context and impact childrens lives in unique ways. For young children, what makes sense and

how they respond to new experiences are fundamentally shaped by the social and cultural contexts to which they

have become accustomed. To ensure that learning experiences are meaningful, relevant, and respectful to

children and their familiesthat is, to be culturally appropriateteachers must have some knowledge of the

DOI: 10.9790/7388-053396102

www.iosrjournals.org

97 | Page

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning Experiences For Secondary...

social and cultural contexts in which children live. Such knowledge helps teachers build on childrens prior

experiences and learning so they can help children progress [10].

Developmentally appropriate practice therefore is teaching that is attuned to childrens ages,

experience, abilities, and interests, and that helps them attain challenging and achievable goals.

Intentional teachers have a purpose for everything that they do, they are thoughtful and prepared, and can

explain the rationale for their decisions and actions to other teachers, administrators, or parents.

Decisions about developmentally appropriate practice are based on knowledge of child development and

learning (what is age appropriate), knowledge about children as individuals, and knowledge of the social

and cultural contexts in which children live (what is culturally appropriate).

The goal of developmentally appropriate education is to optimise the developmental potential of each

child, enhancing children's ability and propensity to think critically, empathetically and imaginatively. The

children must be able to use their multiple intelligences in the real world. There are keys to success in providing

developmentally appropriate practices (DAP) according to [1] argues that focussing on relationship by creating

a caring community of learners is critical. DAP supports the development relationships between adults and

children, among children, among teachers and between families and teachers. Both children and schools benefit

when teachers use knowledge about children's families and experiences outside the classroom to create

individually and culturally relevant learning experiences. [12] asserts that DAP guidelines emphasise school

program-family continuity and regular communication between family and staff, the parent- staff relationship or

partnership.

Understanding age-related child development is opined by [1] as being very important in applying

DAP. Teachers are to aim at creating a learning environment that supports children's growth and development

by safe and healthy interesting experiences and encouraging exploitation and discovery. There's therefore need

to teach to enhance development and learning. Teachers are to present problems to children that are meaningful

and relevant to the child's experience and development. This is a critical issue in the constructivists approach.

[1] contend that knowing each individual child is of essence for DAP to succeed. Developing a

curriculum that considers knowledge about each individual learner including interests, temperaments, gifts,

talents, needs, rate of learning and social and cultural background is what teachers should aim to do. There is

therefore need to construct an appropriate curriculum.

Being flexible and responsive, is one other key factor in achievement of DAP [1]. There is need to

access children's learning and development. In other words, assessment of individual children's development

and learning is essential for planning and implementing appropriate curriculum. Teachers are to be responsive to

the needs of the children. Teachers are also expected to establish partnership with families. DAP evolves from a

deep knowledge of individual children and the context within which they develop and learn. The younger the

child, the more necessary it is for caregivers and teachers to acquire this knowledge through mutually beneficial

relationships with families. The more we learn about teaching and learning in each childhood environments, the

better our children will grow and prosper.

The teaching strategies provide opportunities for active learning experiences that promote children's

active exploration of environment. Children manipulate real objects and learn through hands-on, direct

experiences. Piaget is well known in the field of Educational Psychology for arguing that children construct

knowledge through their active interaction with environments, where mouthing is key for infants ranging 0-2

years of development. There should be opportunities for children to explore, reflect, interact and communicate

with other children (group interactions) and adults, [8].

[13] state the criteria for selecting the method as:

1. Variety: Varied instructional strategies increase the likelihood of efficient learning. This is because students

develop at different rates and learn more quickly through the use of different methods.

2. Scope: This is the range of methods, which must be broad enough to give life experiences. Scope is

difficult to satisfy in that there may be a wide variety of stated methods but none of them may be suitable to

achieve a particular objective.

3. Validity: It means that the teacher must relate specific objectives to specific methods. It is important to note

that a method is only valid if it helps to achieve the objectives.

4. Appropriateness: This implies that the methods should be related to students' interests, abilities and level of

development. Effective learning only takes place when the student is motivated to learn.

5. Relevance: The selection of methods should be related to lives of students. Teachers therefore need the

ability to use the educative potential of the community.

[14] says that psychology, sociology and philosophy of education are considered key disciplines, which

inform the pedagogy of teacher training. It is a foregone conclusion that when student teachers have completed

their training, they become better teachers in the way they carry out their teaching duties. The assumption is that

DOI: 10.9790/7388-053396102

www.iosrjournals.org

98 | Page

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning Experiences For Secondary...

they would have been equipped with the most recently generated methods of teaching, the most current content

and psychologically, sociologically and philosophically correct classroom practices.

On the other hand, [15] say that the theory studied in foundations of education by teachers is too

theoretical and too remote from the classroom. Consequently, teachers may not be able to synchronize theory

with practice. This explains why teachers are unable to organise developmentally appropriate learning

experiences.

In addition, [16] found out that teachers who would have completed their training often have their own

personal theories about teaching in relation to what is important, what is normal and what is right so that they

may not easily accommodate the psychological, sociological and philosophical theories into teaching. They may

continue to use their own personal theories in their teaching, which do not recognise developmentally

appropriate learning experiences for the learners.

The central research question in this study is to find out to what extend in-service teachers were able to organise

learning experiences that were developmentally appropriate.

III.

Methodology

The main design used was the mixed methods (both quantitative and qualitative). Quantitative

approach follows a positivist paradigmatic design. This scientific research paradigm strives to investigate,

confirm and predict law-like patterns of behaviour [17], whereas qualitative research approach is intended to

explain social phenomenon from the inside in a number of ways [18-20] Positivist paradigm is purely

quantitative design and interpretivist paradigm is qualitative design. The interpretivist paradigm partly informs

this study. The interpretive researcher views the participants world experiences from the participants lens [21]

hence we explained our findings as how the intervieews narrated them.

Therefore a mixed methods approach is whereby the two designs complement each other in one study.

The territory of mixed-method designs remains largely uncharted [22]. In this study; we carefully and

thoughtfully applied convergence type of mixed methods, where corroboration and correspondence of results

from different methodological underpinnings complemented all the three in describing triangulation in its true

sense [22].

The sample participants comprised 20 teachers (13 females, 7males), purposively selected from Gweru

urban secondary schools, with a teacher per school teaching a form. Therefore for every school amongst the 5,

every form between one and four had a teacher teaching it. In qualitative design, purposive selection involves

the pursuit of the kind of person whom the researcher is interested in, [21]. For the purposes of this study, we

had to hunt for teachers who were to complete our questionnaires, respond to our interviews and whom we

were to observe teaching. All the teachers / participants were teaching Forms 1 to 4. Form 5 teachers were left

out because at the time of data collection [January to February, 2015], Form 5 learners had not yet commenced

classes.

Same questions were used for both interviews and questionnaires. Interviews were used to gain an indepth understanding of participants and further questions were asked in a bid to gain insights into what

participants were saying through respondents' incidental comments, facial and bodily expressions and tone of

voice. An interviewer acquired information that could not be conveyed in written replies. One can penetrate

initial answers, follow up unexpected clues, redirect the enquiry into a more fruitful channel on the bases of

emerging data and modify categories to provide meaningful analysis of data.

Five teachers were interviewed, all from different schools, and each one of them teaching a different

form, save for the last two who were teaching form 4. Class observations were done using a different cohort of 5

teachers, each from a different secondary school, this time the last 2 teachers were teaching form 1. A teacher

was observed teaching a class only once. The other remaining 10 teachers completed the questionnaire. The

focus of all three methods of data collection was to find out if teachers were able to organise developmentally

appropriate learning experiences for their learners.

3.1 Ethical Considerations

Permission was granted by my University to carry out the study, and the Ministry of Primary and

Secondary Education granted us authority to visit schools. Participants were informed of the research objectives

prior to commencement of the study. They were informed of their freedom to withdraw from the study anytime

they felt like for whatever reason. Participant consent was sought in writing. Confidentiality and anonymity

were granted to participants in writing hence data collecting instruments were alpha-numerically coded for

anonymity.

IV.

Results And Discussion

4.1 Results from questionnaire and Interview

DOI: 10.9790/7388-053396102

www.iosrjournals.org

99 | Page

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning Experiences For Secondary...

All the teachers agreed that age and individual appropriateness make learning experiences

developmentally appropriate. However, half the teachers disagreed that culturally and social context

appropriateness is a curriculum issue that is a very important factor in DAP. It is argued that learning

experiences should be compatible with children's culture to enable them fit into their own society as discussed

previously. The teachers therefore, are not in a hundred percent position to provide learning experiences that are

developmentally appropriate. Additional phases which participants used to explain their understanding of DAP

included the use of more aids and a variety of methods; apart from the content being related to predicted child's

mental capacity, it must be applied to real life experiences; learning that meets the country's needs.

All the 5 interviewed teachers agreed that some developmentally and culturally appropriate knowledge

is not applied in science learning in schools. There is wasted knowledge. For instance, the rural, 15 year old

Zimbabwean African boy, with his catapult around his neck, herding cattle in the tropical rain forest, is quite

aware of many herbs and shrubs, which can be used for medicinal purposes. Such cultural appropriate

knowledge is not captured by modern science curriculum planners.

The technology involved in making the catapult and its application in bringing down a flying bird, the

making of toy cars by 7 year olds, the survival skills when hunting, such skills if harnessed by teachers, it is

developmentally appropriate knowledge suitable for high technological advancement with time.

The challenge with curriculum developers is to downgrade black African rurally home based

generated, unwritten knowledge from the poor stricken villagers as no knowledge at all. We argue here that such

culturally generated knowledge if appropriately harnessed and applied, it could be of great intellectual

investment to our school learners. DAP should fit every child in every environment. We suggest and argue that

we can teach anything to anyone provided we apply DAP. Teachers are called upon to teach in an honest

intellectual manner, that is developmentally appropriate manner.

All teachers agreed that the theory (curriculum issues) which they learnt in the Colleges of Education is

useful and relevant to their work as curriculum implementers. All the five (5) teachers who were interviewed

concurred that they do not wait for all students to understand concepts because the syllabus wont be covered.

This is evidenced by what one teacher said, "if I wait for all students to understand, the syllabus wont be

covered, hence I go own with the fast learners to cover the syllabus." One other teacher said that DAP is good

but its implementation on the ground is a problem because my hands are tied, there are no resources for use and

the syllabus must be covered before students write their examinations. This means that slow learners are not

catered for. Hence teachers take an approach that is characterised by teacher controlled learning, quantifiable

and pre-determined outcomes. In agreement, [9] argues that teachers often emphasise vertical learning i.e. the

learning of skills and facts at the expense of horizontal learning i.e. the deepening of understanding.

Developmentally appropriate learning experiences are time consuming in that an in-depth study through

discussion; open-ended questioning and multiple modes of enquiry require considerable time for both the

teacher and learners. The teachers therefore are working hard to produce students who know what the syllabus

demands, [the psychometric approach, according to [23], rather than creating students who want to know (the

developmental approach)]. They are struggling to meet the requirements of two incompatible systems.

Teachers become exhausted by the end of the day with little time left for thorough lesson preparation.

Large classes of 50-55 learners, make teachers fail to effectively guide students' learning since more time is

spent marking students work. It is important to note that the interactions between the teacher and students can

be increased with small class numbers. [24] asserts that smaller numbers enable the teacher to direct more

attention to individual students and that it also results in more desk space and therefore more free space

available for informal activities or specialist equipment. They all said that class size is a factor in DAP.

Low salaries may force teachers to be absent from work, as they would be trying to make ends meet.

Most teachers are ill due to the AIDS epidemic, they have no vigour for effective work, at times some may go

on indefinite sick leave and this in a way attributes to the heavy load the remaining teachers are having.

Teachers are not consulted when policy issues that affect them are made [25]. They strongly felt that the heads

and deputy heads of schools need some kind of training as administrators. The training could be in terms of

workshops and conferences, such that they can facilitate the teachers' work in the classrooms. [26 p. 5] concurs

when he says that responsibility would be most effectively exercised when the people entrusted with making

decisions are those who are also responsible for carrying them out.

Teaching mixed ability groups is a debatable issue. Half the teachers wanted students streamed while

the other half said students get affected once labelled. Three teachers said that some parents do work hand in

glove with the school. They said that low income parents especially those who do not speak English may face

some barriers when they attempt to collaborate with schools. [27] outlined these barriers as: insufficient time

and energy, lack of language proficiency, feeling of insecurity and low self esteem, lack of understanding about

structure of schools and accepted communication channels, race and class biases on the part of the school

personnel and perceived lack of welcome by teachers and administrators, all these affect implementation of

DAP.

DOI: 10.9790/7388-053396102

www.iosrjournals.org

100 | Page

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning Experiences For Secondary...

4.2 Results from observation guide

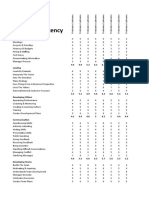

As shown by Table 1, interaction patterns are just teacher-pupil and pupil- pupil / group interactions.

These are teacher directed hence time was not sufficient for an in-depth study.

Table 1: What was observed at Secondary Schools?

1. Interaction Patterns

Teacher- Pupil interaction

Pupil-pupil interaction

2. Organisation of Learning experiences

Learning in groups

Individual written exercises

Lecture method

Group work

Chalk and board

A few text-books

Pupils exercise books

Question and answer

Texts and written exercises

Homework

3. Teacher methodology

4. Learning materials

5. Feedback

Organisation of learning experiences included, group work and individual exercises. Variety of

teaching methods was very limited as shown above.

It is mainly teacher exposition or lecturer method and group work. Learning materials are just chalk

and board, children's text and exercise books. A few textbooks of about 5-10 were shared amongst 50 students.

We were told that the schools were encouraging the parents to buy textbooks for their children, but most of the

parents did not afford. Feedback was mostly in the question and answer form and teachers seemed to call upon

the same students who seemed to be academically gifted. Individual written exercises and tests as well as

homework questions were also used. Teachers used teacher centredness approach at the expense of childcentredness. Teachers taught for examinations and not for true understanding which normally leads to

application of content learnt and skills gained.

The teachers are worn-out and tired. There is no fire in them. One lady teacher said in local

shona language izvi hazvichabatsira izvi, mari yacho haikwani, hauzivi kuti uchaiwana riini, kumba land-lord

arikuvava kuda rent yake, magetsi hakuna, mvura hakuna, chokudya zero. Literally, the lady teacher was

complaining about the economic situation in the country, where salaries are low, salary dates are no longer

known, rentals, electricity and water bills are due to be paid, meanwhile they are bankrupt. Building on this

argument, the evidence suggests low motivation on the part of teachers. Lack of motivation of a teacher affects

several classes which one teaches in a school. Teachers input to his/her work may is compromised. This will in

turn leads to high failure rate and high illiteracy. High illiterate post secondary students signifies diminishing

skilled workforce, the economy of the country suffers and less money will be spent on education, leading to

high prevalence of illiteracy again, resulting in a vicious cycle.

V.

Conclusions

Not all teachers fully understood DAP. The theory they got during training is not compatible in part,

with the curriculum that is examination oriented. The teachers failed to provide developmentally appropriate

learning experiences as a result of the constraints such as heavy teaching loads, low salaries, lack of resources,

large classes, fragmented schemes that demand more clerical work and the AIDS epidemic. As long as the

education system considers coverage of a prescribed modern curriculum, mastery of discrete skills and

increasing achievement, teachers would not be able to provide developmentally appropriate learning

experiences. Teachers actually struggle to meet the requirements of these two incompatible systems. The

Zimbabwean education system has been greatly influenced by the cultural transmission ideology where teacher's

job is to direct instruction of information and rule. With all these challenges, teachers are unable to provide

developmentally appropriate learning experiences.

The need to reduce class size or teacher-pupil ratio to enable the teacher to give individual attention

and less time to mark written assignments, was recommended. The teaching loads and number of schemes are to

be reduced appropriately such that teachers are in a position to make teaching aids, and thoroughly prepare their

lessons.

Teachers, through their teachers forums like Zimbabwe Teachers Association are supposed to have

their voices heard by policy makers. The schools must encourage and provide opportunities for meaningful

family involvement which play a critical role in bridging the gulf between the home and the school. Teachers

are to be made effective and committed to their work through motivational remunerations and working

DOI: 10.9790/7388-053396102

www.iosrjournals.org

101 | Page

Implementing Developmentally Appropriate Learning Experiences For Secondary...

conditions. The government, through its Ministry of Education, has to provide realistic educational grants to

procure sufficient teaching and learning resources.

The number of schools and sample of participants studied was small hence the findings lack external

validity. However, no external validity was expected since the choice of participants was purposive. Further

studies, perhaps using different designs, bigger sample from a wider environmental cultural setting, could

perhaps yield different and more reliable and valid findings.

References

[1].

[2].

[3].

[4].

[5].

[6].

[7].

[8].

[9].

[10].

[11].

[12].

[13].

[14].

[15].

[16].

[17].

[18].

[19].

[20].

[21].

[22].

[23].

[24].

[25].

[26].

[27].

Downs, J., Blagojevic, B., Labas, L., Kendrick, M., & Maeverde, J. (2005). Thoughtful

Teaching: Developmentally

Appropriate Practice. In Growing Ideas Toolkit (pp. 34). Orono, ME: The University of Maine Center for Communitv

Inclusion and

Disability Studies. Retrieved from http://www.umaine.edu/cci/ec/growingideas/daptip.htm

Bredekamp, S. (Ed.) (1987). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through

age eight. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Bredekamp, S. & Rosegrant, T. (1992). Reaching Potentials: introduction. In S. Bredekamp & T.Rosegrant (Eds.), Reaching

potentials: Appropriate curriculum and assessment for young children. Washington, DC: National Association for the

Education of Young Children.

Marsh, C. J. & Willis, G. (2003). Curriculum: Alternative approaches, ongoing issues. (3 rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill

Prentice Hall.

Lawton, D. (1982). Social Change, Educational Theory and Curriculum Planning. London: Hodder and Stughton.

Bowman, B. T. (1994). The challenge of diversity. Phi Delta Kappan, November, 218-224.

Bowman, B. T. (1992). Reaching potentials of minority children through developmentally and culturally appropriate programs. In

S. Bredekamp & T. Rosegrant (Eds.), Reaching potentials: Appropriate curriculum and assessment for young children. Washington,

DC National Association for the Education of Young Children.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (1996). Developmentally appropriate practice

in

early

childhood programs serving children from birth

through age 8 (NAEYC position statement) Retrived from Http: //www.

naeyc.org/resources/position statements/daptoc.htm

Kostelnik, M. (1992). Myths associated with developmentally appropriate programs. Young Children, 47(40) 17-23.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (2009). Developmentally Appropriate Learning Eperiences.

Downloaded from www.naeyc.org/dap 22/08/2013

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development:Research

perspectives.

Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723-742.

Powell, D. (1994). Parents, pluralism, and the NAEYC statement on developmentally appropriate practice. In B. L. Mallory & R.

S. New, (Eds.), Diversity and developmentally appropriate practices. New York: Teachers College Press.

Ornstein. A. C. and Hunkins, F. D. (2009. Curriculum Foundations, Principles and Theory. Boston: Allyn and. Bacon.

Fontana, D. (ed.), (1968). Educational Psychology: Plato, Piaget and Scientific Psychology. Oxford: Carfax Publishers.

Branford, & Vye. (1989). The "Case" Method in Modern Educational Psychology Texts. In K. K. Block (Ed.), Teaching and

Teacher Education (Vol. 12, pp. 483-500). Oxford: Elsevier Science Ltd.

Claxton, G. (1989). Being a Teacher: A Positive Approach to Change and Stress. London: Cassel

Educational Limited.

Taylor, P. C., & Medina, M. N. D. (2013). Educational research paradigms: From positivism to multiparadigmatic. Journal for

Meaning-Centered Education. Retrieved from http://www.meaningcentered.org/educational-researchparadigms-from-positivism-tomultiparadigmatic/journal/volume-01/.

Fouche, C. B., & Schurink, W. (2011). Qualitative research designs. In A. S. De Vos, H.Strydom, C. B. Fouche & C. S. L. Delport

(Eds.), Research at grassroots. Pretoria:VanSchaik.

Gudyanga, E. (2014). Anthropomorphic notion of atoms, the etiology of pedagogical and epistemological learning proactive

interference among Chemistry learners: Implications. Science Journal of Education, 2(2), 65-70.

Gudyanga, E., & Madambi, T. (2014). Pedagogics of chemical bonding in Chemistry; perspectives and potential for progress: The

case of Zimbabwe secondary education. International Journal of Secondary Education, 2(1), 11-19. doi:

10.11648/ijsedu.20140201.13

Gudyanga, E. (2015(b)). Transforming HIV and AIDS education curriculum: The voices of Zimbabwean secondary school

Guidance and Counselling teachers as curriculum planners. PhD Thesis in Progress. Education. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan

University.

Gudyanga, E., Moyo, S., & Gudyanga, A. (2015). Navigating Sexuality and HIV/AIDS: Insights and Foresights of Zimbabwean

adolescents. British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural Science, 7(1), 17-24.

Elkind, D. (1991). Developmentally appropriate practice: A case study of educational inertia. In S.

L. Kagan (Ed.), The care

and education of America's young children:

obstacles and opportunities. Chicago, III: The University of Chicago Press.

Marsh, C. J . (1997). Perspectives, Key Concepts for Understanding Curriculum. London: The Palmer Press.

Mufuka, K. N., & Tauya, T. (2013). New Fallacies about HIV / AIDS in Zimbabwe. African Educational Research Journal, 1(1),

51-57.

Brady, L. (1997). Curriculum Development in Australia. Sydney: Prentice-Hall.

Fruchter, N., Galletta, A. & White, J. L. (1992). New directions in parent involvement. Washington. D.C. Academy for Educational

Development.

DOI: 10.9790/7388-053396102

www.iosrjournals.org

102 | Page

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Define Research and Characteristics of ResearchDokument15 SeitenDefine Research and Characteristics of ResearchSohil Dhruv94% (17)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Kinesics, Haptics and Proxemics: Aspects of Non - Verbal CommunicationDokument6 SeitenKinesics, Haptics and Proxemics: Aspects of Non - Verbal CommunicationInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Applied Linguistics Lecture 2Dokument17 SeitenApplied Linguistics Lecture 2Dina BensretiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attitude and Perceptions of University Students in Zimbabwe Towards HomosexualityDokument5 SeitenAttitude and Perceptions of University Students in Zimbabwe Towards HomosexualityInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- "I Am Not Gay Says A Gay Christian." A Qualitative Study On Beliefs and Prejudices of Christians Towards Homosexuality in ZimbabweDokument5 Seiten"I Am Not Gay Says A Gay Christian." A Qualitative Study On Beliefs and Prejudices of Christians Towards Homosexuality in ZimbabweInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Extrovert and Introvert Personality in Second Language AcquisitionDokument6 SeitenThe Role of Extrovert and Introvert Personality in Second Language AcquisitionInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Socio-Ethical Impact of Turkish Dramas On Educated Females of Gujranwala-PakistanDokument7 SeitenSocio-Ethical Impact of Turkish Dramas On Educated Females of Gujranwala-PakistanInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Proposed Framework On Working With Parents of Children With Special Needs in SingaporeDokument7 SeitenA Proposed Framework On Working With Parents of Children With Special Needs in SingaporeInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- An Evaluation of Lowell's Poem "The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket" As A Pastoral ElegyDokument14 SeitenAn Evaluation of Lowell's Poem "The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket" As A Pastoral ElegyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of The Implementation of Federal Character in Nigeria.Dokument5 SeitenAssessment of The Implementation of Federal Character in Nigeria.International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Technologies On Society: A ReviewDokument5 SeitenThe Impact of Technologies On Society: A ReviewInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)100% (1)

- Edward Albee and His Mother Characters: An Analysis of Selected PlaysDokument5 SeitenEdward Albee and His Mother Characters: An Analysis of Selected PlaysInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Review of Rural Local Government System in Zimbabwe From 1980 To 2014Dokument15 SeitenA Review of Rural Local Government System in Zimbabwe From 1980 To 2014International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Visual Analysis of Symbolic and Illegible Indus Valley Script With Other LanguagesDokument7 SeitenComparative Visual Analysis of Symbolic and Illegible Indus Valley Script With Other LanguagesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Investigation of Unbelief and Faith in The Islam According To The Statement, Mr. Ahmed MoftizadehDokument4 SeitenInvestigation of Unbelief and Faith in The Islam According To The Statement, Mr. Ahmed MoftizadehInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Relationship Between Social Support and Self-Esteem of Adolescent GirlsDokument5 SeitenRelationship Between Social Support and Self-Esteem of Adolescent GirlsInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Human Rights and Dalits: Different Strands in The DiscourseDokument5 SeitenHuman Rights and Dalits: Different Strands in The DiscourseInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Topic: Using Wiki To Improve Students' Academic Writing in English Collaboratively: A Case Study On Undergraduate Students in BangladeshDokument7 SeitenTopic: Using Wiki To Improve Students' Academic Writing in English Collaboratively: A Case Study On Undergraduate Students in BangladeshInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Lute Against Doping in SportDokument5 SeitenThe Lute Against Doping in SportInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Designing of Indo-Western Garments Influenced From Different Indian Classical Dance CostumesDokument5 SeitenDesigning of Indo-Western Garments Influenced From Different Indian Classical Dance CostumesIOSRjournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Importance of Mass Media in Communicating Health Messages: An AnalysisDokument6 SeitenImportance of Mass Media in Communicating Health Messages: An AnalysisInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Transforming People's Livelihoods Through Land Reform in A1 Resettlement Areas in Goromonzi District in ZimbabweDokument9 SeitenTransforming People's Livelihoods Through Land Reform in A1 Resettlement Areas in Goromonzi District in ZimbabweInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Madarsa Education in Empowerment of Muslims in IndiaDokument6 SeitenRole of Madarsa Education in Empowerment of Muslims in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Beowulf: A Folktale and History of Anglo-Saxon Life and CivilizationDokument3 SeitenBeowulf: A Folktale and History of Anglo-Saxon Life and CivilizationInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Motivational Factors Influencing Littering in Harare's Central Business District (CBD), ZimbabweDokument8 SeitenMotivational Factors Influencing Littering in Harare's Central Business District (CBD), ZimbabweInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Classical Malay's Anthropomorphemic Metaphors in Essay of Hikajat AbdullahDokument9 SeitenClassical Malay's Anthropomorphemic Metaphors in Essay of Hikajat AbdullahInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Women Empowerment Through Open and Distance Learning in ZimbabweDokument8 SeitenWomen Empowerment Through Open and Distance Learning in ZimbabweInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- An Exploration On The Relationship Among Learners' Autonomy, Language Learning Strategies and Big-Five Personality TraitsDokument6 SeitenAn Exploration On The Relationship Among Learners' Autonomy, Language Learning Strategies and Big-Five Personality TraitsInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Substance Use and Abuse Among Offenders Under Probation Supervision in Limuru Probation Station, KenyaDokument11 SeitenSubstance Use and Abuse Among Offenders Under Probation Supervision in Limuru Probation Station, KenyaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Micro Finance and Women - A Case Study of Villages Around Alibaug, District-Raigad, Maharashtra, IndiaDokument3 SeitenMicro Finance and Women - A Case Study of Villages Around Alibaug, District-Raigad, Maharashtra, IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Design Management, A Business Tools' Package of Corporate Organizations: Bangladesh ContextDokument6 SeitenDesign Management, A Business Tools' Package of Corporate Organizations: Bangladesh ContextInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On The Television Programmes Popularity Among Chennai Urban WomenDokument7 SeitenA Study On The Television Programmes Popularity Among Chennai Urban WomenInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Let A Thousand Flowers Bloom: A Tour of Logical Pluralism: Roy T. CookDokument13 SeitenLet A Thousand Flowers Bloom: A Tour of Logical Pluralism: Roy T. CookDenisseAndreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nature of PhilosophyDokument15 SeitenNature of PhilosophycathyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Middle Term FiguresDokument19 SeitenMiddle Term FiguresShen SeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- HELEN A. ABEJUELA Who Is A Lifelong LearnerDokument2 SeitenHELEN A. ABEJUELA Who Is A Lifelong LearnerHelen Alensonorin100% (3)

- Pragmatism and Logical PositivismDokument3 SeitenPragmatism and Logical PositivismAnum MubasharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Psychology: 1.early PsychologistsDokument11 SeitenEducational Psychology: 1.early Psychologistszainab jabinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ancient Path of Supreme Truth, God-Realization, Freedom and HappinessDokument315 SeitenThe Ancient Path of Supreme Truth, God-Realization, Freedom and Happinessrahulkr89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civics Lesson 2 Why Do People Form GovernmentsDokument3 SeitenCivics Lesson 2 Why Do People Form Governmentsapi-252532158Noch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral Finance: An IntroductionDokument3 SeitenBehavioral Finance: An IntroductionAdil Khan100% (1)

- Metaphysics and Quantum PhysicsDokument2 SeitenMetaphysics and Quantum PhysicsAnthony J. Fejfar92% (12)

- The Kolb Learning Cycle in American Board of Surgery In-Training Exam Remediation: The Accelerated Clinical Education in Surgery CourseDokument53 SeitenThe Kolb Learning Cycle in American Board of Surgery In-Training Exam Remediation: The Accelerated Clinical Education in Surgery Coursevaduva_ionut_2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Training Needs Analysis Template Leadership Skills ExampleDokument4 SeitenTraining Needs Analysis Template Leadership Skills ExampleJona SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MG University BA PSY Programme Syllabi CBCSS - 2010 - EffectiDokument61 SeitenMG University BA PSY Programme Syllabi CBCSS - 2010 - EffectiSuneesh LalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Byd Forklift 1 72gb PDF Service and Part ManualDokument23 SeitenByd Forklift 1 72gb PDF Service and Part Manualjoshualyons131198xtj100% (135)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in ECCEDokument5 SeitenDetailed Lesson Plan in ECCEflorie AquinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plato's IdealismDokument4 SeitenPlato's IdealismachillesrazorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Interview ScriptDokument5 SeitenTeacher Interview Scriptapi-288924191Noch keine Bewertungen

- JELLT - The Impact of Colors PDFDokument15 SeitenJELLT - The Impact of Colors PDFM Gidion MaruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 4 The Scientific Method in Geography SKDokument13 SeitenLecture 4 The Scientific Method in Geography SKJoseph Zotoo100% (4)

- Theme: What Study Skills Do I Need To Succeed in Senior High School?Dokument52 SeitenTheme: What Study Skills Do I Need To Succeed in Senior High School?Gianna GaddiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Major barriers to listening & remediesDokument5 SeitenMajor barriers to listening & remediesManohar GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language TheoriesDokument2 SeitenLanguage TheoriesmanilynNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effective TeacherDokument9 SeitenEffective TeacherZaki ZafriNoch keine Bewertungen

- A. Recall The Previous LessonDokument4 SeitenA. Recall The Previous LessonBernie IbanezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wordsworth On Excitement and PleasureDokument3 SeitenWordsworth On Excitement and PleasureNdung'u JuniorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociolinguistics: - Competence and Performance - Communicative Competence and Its Four ComponentsDokument11 SeitenSociolinguistics: - Competence and Performance - Communicative Competence and Its Four ComponentsTomas FlussNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neuro SemanticsDokument12 SeitenNeuro SemanticsAGW VinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding The Self: Andres Soriano Colleges of Bislig Ite/Tvet DepartmentDokument8 SeitenUnderstanding The Self: Andres Soriano Colleges of Bislig Ite/Tvet DepartmentDarioz Basanez LuceroNoch keine Bewertungen