Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

2015 Egalitarians

Hochgeladen von

Bashir MureiOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

2015 Egalitarians

Hochgeladen von

Bashir MureiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

2015

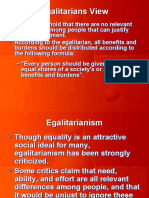

EGALITARIANS

VIEW

Some egalitarians have tried to strengthen their position by distinguishing two different

kinds of equality: political equality and economic equality. Political equality refers to an

equal participation in, and treatment by, the means of controlling and directing the political

system. This includes equal rights to participate in the legislative process, equal civil

liberties, and equal rights to due process. Economic equality refers to equality of income

and wealth and equality of opportunity. The criticisms leveled against equality, according

to some egalitarians, only apply to economic equality and not to political equality.

Capitalists argue that a society's benefits should be distributed in proportion to what each

individual contributes to society. According to this capitalist view of justice, when people

engage in economic exchanges with each other, what a person gets out of the exchange

should be at least equal in value to what he or she contributed. Justice requires, then, that

the benefits a person receives should be proportional to the value of his or her contribution.

Quite simply:

Benefits should be distributed according to the value of the contribution the

individual makes to a society, a task, a group, or an exchange.

The main question raised by the contributive principle of distributive justice is how the

"value of the contribution" of each individual is to be measured. One long-lived tradition

has held that contributions should be measured in terms of work effort. The more effort

people put forth in their work, the greater the share of benefits to which they are entitled.

The harder one works, the more one deserves. A second important tradition has held that

contributions should be measured in terms of productivity. The better the quality of a

person's contributed product, the more he or she should receive.

Socialists address this concern by stating that the benefits of a society should be distributed

according to need, and that people should contribute according to their abilities. Critics of

socialism contend that workers in this system would have no incentive to work and that the

principle would obliterate individual freedom.

The libertarian view of justice is markedly different, of course. Libertarians consider it

wrong to tax someone to provide benefits to someone else. No way of distributing goods

can be just or unjust apart from an individual's free choice. Robert Nozick, a leading

libertarian, suggests this principle as the basic principle of distributive justice:

From each according to what he chooses to do, to each according to what he

makes for himself (perhaps with the contracted aid of others) and what others

choose to do for him and choose to give him of what they've been given

previously (under this maxim) and haven't yet expended or transferred.

If I choose to help another, that is fine, but I should not be forced to do so. Critics of

this view point out that freedom from coercion is a value, but not necessarily the most

important value, and libertarians seem unable to prove outright that it is more important to be

free than, say, to be fed. If each person's life is valuable, it seems as if everyone should be

cared for to some extent. A second related criticism of libertarianism claims that the

libertarian principle of distributive justice will generate unjust treatment of the

disadvantaged. Under the libertarian principle, a person's share of goods will depend wholly

on what the person can produce through his or her own efforts or what others choose to give

the person out of charity

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Lecture 10Dokument15 SeitenLecture 10Hassan AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 (D) - Chapter Justice and FairnessDokument5 SeitenChapter 2 (D) - Chapter Justice and FairnessAbhishek Kumar SahayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice and FairnessDokument5 SeitenJustice and FairnessGirl Lang Ako100% (1)

- ETHICAL PRINCIPLES IN BUSINESSDokument22 SeitenETHICAL PRINCIPLES IN BUSINESSWulan Rezky AmalyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics and Business EthicsDokument19 SeitenEthics and Business EthicsIza longgakitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice and FairnessDokument6 SeitenJustice and Fairnesszmarcuap1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kajal Singh M.A. Political Science 2 Semester 22/ 62/ HP/025Dokument7 SeitenKajal Singh M.A. Political Science 2 Semester 22/ 62/ HP/025EveniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MD Hashir Khan Jurisprudence Sem 4Dokument6 SeitenMD Hashir Khan Jurisprudence Sem 4Hashir KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- EQUALITY PPT - TANGO-ANDokument15 SeitenEQUALITY PPT - TANGO-ANYuri YuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice and Fairness: Rawls' Theory of Distributive JusticeDokument30 SeitenJustice and Fairness: Rawls' Theory of Distributive JusticeMariz SungaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liberal Equality Vs Socialist Equality - Uritu Andra 1211EBDokument6 SeitenLiberal Equality Vs Socialist Equality - Uritu Andra 1211EBAmara CostachiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Utilitarianism & Related Concepts: Sub: Ethics & CSR By: Akanksha RawatDokument28 SeitenUtilitarianism & Related Concepts: Sub: Ethics & CSR By: Akanksha RawatVandana ŘwţNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7.2. Justice and FairnessDokument30 Seiten7.2. Justice and FairnessDiane RamentoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social JusticeDokument9 SeitenSocial JusticeKesavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice and FairnessDokument22 SeitenJustice and FairnessCharles Ronald GenatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of Justice - 1Dokument14 SeitenTheory of Justice - 1John Leo R. Española,100% (1)

- GEC 108 10 Justice and FairnessDokument3 SeitenGEC 108 10 Justice and Fairnessjohndanielgraida28Noch keine Bewertungen

- 20190717112458D6038 - 4 - Ethical Principles in BusinessDokument38 Seiten20190717112458D6038 - 4 - Ethical Principles in BusinessVeronica HenyNoch keine Bewertungen

- FRAMEWORK AND PRINCIPLES – CHAPTER 6Dokument31 SeitenFRAMEWORK AND PRINCIPLES – CHAPTER 6Cyrus LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics 101Dokument20 SeitenEthics 101Jacky Afundar BandalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice and FairnessDokument2 SeitenJustice and FairnessKyoka KatagiriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice and Fairness Distributive JusticeDokument12 SeitenJustice and Fairness Distributive JusticeBlack KnightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rawls' Theory of Social JusticeDokument13 SeitenRawls' Theory of Social JusticeAdada Mohammed Abdul-Rahim Bature100% (1)

- Political Philosophy Term Paper Shefali Jha Ma'AmDokument5 SeitenPolitical Philosophy Term Paper Shefali Jha Ma'AmEveniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Background On Rawls' Liberal EgalitarianismDokument5 SeitenBackground On Rawls' Liberal EgalitarianismSHAKOOR BHATNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of JusticeDokument4 SeitenTheories of JusticeMohandas Periyasamy100% (1)

- Kant and Rights TheoryDokument18 SeitenKant and Rights Theorycynthia karylle natividadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q1. Distributive Justice Is About Balancing Collective Welfare, Individual Freedom, and Human Virtues. ExplainDokument5 SeitenQ1. Distributive Justice Is About Balancing Collective Welfare, Individual Freedom, and Human Virtues. ExplainHashir KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Values: Liberty and Equality I. Political PhilosophyDokument3 SeitenSocial Values: Liberty and Equality I. Political Philosophydjoseph_1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Distributive Justice: Ayhee Marie David Jhollie Felipe Mark Gabriel DangaDokument10 SeitenDistributive Justice: Ayhee Marie David Jhollie Felipe Mark Gabriel DangaMark Gabriel DangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Different Moral TheoriesDokument4 SeitenDifferent Moral TheoriesSoora LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- BE Topic 3: Justice and Free Market SystemDokument5 SeitenBE Topic 3: Justice and Free Market SystemSabrina AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social JusticeDokument9 SeitenSocial Justicemalikmukku90Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Principles in BusinessDokument41 SeitenEthical Principles in BusinessDevansh SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Midterms AbantasDokument5 SeitenMidterms AbantasAmer Shalem Diron AbantasNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is A Just Society, Lec 4Dokument26 SeitenWhat Is A Just Society, Lec 4Harshit KrishnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Principles in BusinessDokument17 SeitenEthical Principles in BusinessDavid KellyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 - Rawls Theory of JusticeDokument25 Seiten11 - Rawls Theory of JusticeELYSSA MANANSALANoch keine Bewertungen

- Deontology TheoryDokument25 SeitenDeontology TheorySyed HafizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice and EqualityDokument33 SeitenJustice and EqualityHarshil DaveNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAROHOMDokument9 SeitenMAROHOMJack AninoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule Utilitarianism, Equality, and JusticeDokument13 SeitenRule Utilitarianism, Equality, and JusticeShivansh soniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Triple Talaq, Right to Privacy and Legal Rights ExplainedDokument19 SeitenTriple Talaq, Right to Privacy and Legal Rights ExplainedsamiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Ethics ReviewDokument8 SeitenBusiness Ethics Reviewrajkranga100% (1)

- 4.justice and Economic DistributionDokument30 Seiten4.justice and Economic DistributionMuneer Hussain90% (10)

- Distributive JusticeDokument20 SeitenDistributive JusticeAshera Monasterio100% (1)

- Principles of Distributive JusticeDokument9 SeitenPrinciples of Distributive JusticeSagargn SagarNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSWE-001/2019-20 Introduction To Social Work 1) Discuss Social Justice and Social Policy As Social Work Concepts. 20Dokument13 SeitenBSWE-001/2019-20 Introduction To Social Work 1) Discuss Social Justice and Social Policy As Social Work Concepts. 20ok okNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3Dokument29 SeitenChapter 3Syifa FauziahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisprudence: Social JusticeDokument5 SeitenJurisprudence: Social JusticeMR. ISHU POLASNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Utilitarianism and KantianismDokument14 Seiten4 Utilitarianism and KantianismDeepak DeepuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reconciling Liberty and EqualityDokument38 SeitenReconciling Liberty and EqualityJeremiah Miko LepasanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BEL311 En. Ariff Acd3Tb: Social Justice in Economics by Ana and Pika Issue: Capitalist VS Islamic Economic SystemDokument6 SeitenBEL311 En. Ariff Acd3Tb: Social Justice in Economics by Ana and Pika Issue: Capitalist VS Islamic Economic SystemRohana MislamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of RightsDokument18 SeitenTypes of RightsMohamed Abulinein0% (1)

- Lesson 10: Justice and Fairness: Promoting The Common GoodDokument33 SeitenLesson 10: Justice and Fairness: Promoting The Common GoodManiya Dianne Reyes100% (1)

- Chapter-10-Group 4 (Social Justice)Dokument12 SeitenChapter-10-Group 4 (Social Justice)Mary Ann AlterosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of Justice LLM Chapter OneDokument28 SeitenTheory of Justice LLM Chapter OneUmaar MaqboolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6 JusticeDokument8 SeitenChapter 6 JusticeJanella TamagNoch keine Bewertungen

- EthicsDokument11 SeitenEthicsredgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Painful Birth: How Chile Became a Free and Prosperous SocietyVon EverandPainful Birth: How Chile Became a Free and Prosperous SocietyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is It A New Thinking?Dokument5 SeitenIs It A New Thinking?Bashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Production PlanningDokument2 SeitenProduction PlanningBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Management BCOM NotesDokument4 SeitenMarketing Management BCOM NotesBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Procurement Retention ScheduleDokument6 SeitenProcurement Retention ScheduleBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dispute ResolutionDokument1 SeiteDispute ResolutionBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business and Information SystemsDokument17 SeitenBusiness and Information SystemsBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainable marketing principlesDokument4 SeitenSustainable marketing principlesBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Marketing TwoDokument90 SeitenIntroduction To Marketing TwoBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Is Communication ImportantDokument1 SeiteWhy Is Communication ImportantBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Privacy in KENYADokument1 SeiteConsumer Privacy in KENYABashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law As Per My KnowledgeDokument2 SeitenLaw As Per My KnowledgeBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Perceived ValueDokument1 SeiteCustomer Perceived ValueBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Management Exam QuestionsDokument2 SeitenMarketing Management Exam QuestionsBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salesmanshipcomplete NotesDokument42 SeitenSalesmanshipcomplete NotesBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBA Notes AdvertisingDokument4 SeitenMBA Notes AdvertisingBashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sales Manegement BBM 333Dokument1 SeiteSales Manegement BBM 333Bashir MureiNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR Timothee Ouattara, The Intersectionality of Black Women's LeadershipDokument21 SeitenDR Timothee Ouattara, The Intersectionality of Black Women's LeadershipAnnalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feminist Movement And/or Feminist CriticismDokument10 SeitenFeminist Movement And/or Feminist Criticismnoddy_tuliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relevance of Marxism TodayDokument3 SeitenThe Relevance of Marxism Todayamolpatiala100% (1)

- 9 Liberal FeminismDokument10 Seiten9 Liberal FeminismTitis Dwi RachmawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capitalism in Hunger GamesDokument3 SeitenCapitalism in Hunger GamesBen100% (1)

- Lecture 6 Conflict Theory, Marx and NeoMarxist ON FAMILYDokument6 SeitenLecture 6 Conflict Theory, Marx and NeoMarxist ON FAMILYTafadzwa Nicolle KahariNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief Analysis of Fukuyama's Thesis ''The End of History - (#118847) - 100889Dokument3 SeitenA Brief Analysis of Fukuyama's Thesis ''The End of History - (#118847) - 100889Ichraf KhechineNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Note On Burke's Vindication of Natural SocietyDokument6 SeitenA Note On Burke's Vindication of Natural SocietyWendel CintraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cause-Effect EssayDokument4 SeitenCause-Effect EssayOanh KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- She No Longer WeepsDokument4 SeitenShe No Longer Weepsashleigh chakaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faizan Yousuf ShanDokument14 SeitenFaizan Yousuf ShanFaizan Yousuf ShanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palstro EssayDokument5 SeitenPalstro Essayapi-388605393Noch keine Bewertungen

- Western Political Thought Block 2 PDFDokument107 SeitenWestern Political Thought Block 2 PDFआई सी एस इंस्टीट्यूटNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sharon Stevens - ArtivistDokument29 SeitenSharon Stevens - ArtivistSharon StevensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fourth Wave FeminismDokument4 SeitenFourth Wave FeminismjessicaterritoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL IDEOLOGIES CeuDokument10 SeitenCONTEMPORARY POLITICAL IDEOLOGIES CeuCarlos León Moya0% (1)

- Can Feminism be Reconciled with Islamic TeachingsDokument4 SeitenCan Feminism be Reconciled with Islamic TeachingsrasheedarshadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political Science MCQs Practice Test 79 PDFDokument4 SeitenPolitical Science MCQs Practice Test 79 PDFAalisha PriyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Women Struggle Against Patriarchy in The Girl on the TrainDokument18 SeitenWomen Struggle Against Patriarchy in The Girl on the Trainahmadp777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Feminist Jurisprudence ExplainedDokument4 SeitenCritical Feminist Jurisprudence ExplainedA2 Sir Fan PageNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Politics and Governance: (Quarter 1 - Module 2)Dokument12 SeitenPhilippine Politics and Governance: (Quarter 1 - Module 2)Dennis Jade Gascon Numeron100% (3)

- K AnswersDokument451 SeitenK AnswersMark McGovernNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feminism SpeechDokument2 SeitenFeminism SpeechPaula Gonzalez ArmendarizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maoist Internationalist Movement - On Colonialism, Imperialism, and Revolutionary StrategyDokument74 SeitenMaoist Internationalist Movement - On Colonialism, Imperialism, and Revolutionary StrategyvendettamyspaceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ideology of Mao ZedongDokument2 SeitenIdeology of Mao ZedongCrimson BirdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political Parties and Party SystemsDokument12 SeitenPolitical Parties and Party SystemsFyna BobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Justice in The Age of Identity PoliticsDokument68 SeitenSocial Justice in The Age of Identity PoliticsAndrea AlvarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dalit Capital: State, Markets and Civil Society in Urban IndiaDokument2 SeitenDalit Capital: State, Markets and Civil Society in Urban IndiaVivek SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sidney e Parker Individualist AnarchismDokument6 SeitenSidney e Parker Individualist AnarchismLiam ScullyNoch keine Bewertungen

- J.S. Mill's On LibertyDokument6 SeitenJ.S. Mill's On LibertySzilveszter FejesNoch keine Bewertungen