Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Corpo Case Digests - Set4 PDF

Hochgeladen von

Chezca MargretOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Corpo Case Digests - Set4 PDF

Hochgeladen von

Chezca MargretCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CORPORATION

LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

WESTERN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY vs. SALAS

G.R. No. 113032 August 21, 1997

FACTS:

Ricardo, Salvador, Soledad, Antonio, and Richard Salas were the

controlling members of the Board of Trustees of WIT, a non-stock

corporation engaged in the operation of an educational institution.

According to Villasis et al. (petitioners and minority stockholders), a

special board meeting was held on June 1, 1986, wherein Resolution

No. 48 series of 1986 was passed. The resolution granted monthly

compensation (9T/mo for the Chairman; 3.5T Vice Chairman; 3.5T

Corporate Sec; 3.5T Corporate Treasurer) to the Salas[es] as corporate

officers, retroactive June 1, 1985. Allegedly, the resolution was dated

March 30, 1986, not June 1, 1986.

In 1991, Villasis et al. consequently filed a criminal complaint against

the Salas[es] for falsification of public document and for estafa. The first

charge was anchored on the WITs income statement for 1985-1986

with SEC reflecting the disbursement for the officers compensation

based on the resolution, making it appear that it was passed on March

30, when it truth it was passed on June 1, a date not covered by the

corporations fiscal year (May 1, 1985-April 30, 1986). Meanwhile, the

estafa was based on the officers disbursement of funds albeit

unauthorized, and despite objections made in annual stockholders

meeting, they refused to rectify the same.

RTC Iloilo: Acquitted the Salas[es]. (NB: WIT filed motion to intervene,

stating that Villasis et al.s lawyer was not the corporations counsel;

thus, they did not represent the corporation and that WIT sought the

dismissal of the petition. But this is weird, dont you think? Bakit

petitioner pa din ang WIT dito, ganyan?)

ISSUE:

WON the resolution was valid, i.e. it did not violate Section 30 of the

Code.

HELD:

Yes.

Sec.

30.Compensation

of

directors.

In

the

absence

of

any

provision

in

the

by-laws

fixing

their

compensation,

the

directors

shall

not

receive

any

compensation,

as

such

directors,

except

for

reasonable

per

diems:

Provided,

however,

That

any

such

compensation

(other

than

per

diems)

may

be

granted

to

directors

by

the

vote

of

the

stockholders

representing

at

least

a

majority

of

the

outstanding

capital

stock

at

a

regular

or

special

stockholders'

meeting.

In

no

case

shall

the

total

yearly

compensation

of

directors,

as

such

directors,

exceed

ten

(10%)

percent

of

the

net

income

before

income

tax

of

the

corporation

during

the

preceding

year.

There

is

no

argument

that

directors

or

trustees,

as

the

case

may

be,

are

not

entitled

to

salary

or

other

compensation

when

they

perform

nothing

more

than

the

usual

and

ordinary

duties

of

their

office.

This

rule

is

founded

upon

a

presumption

that

directors/trustees

render

service

gratuitously,

and

that

the

return

upon

their

shares

adequately

furnishes

the

motives

for

service,

without

compensation.

Under

the

foregoing

section,

there

are

only

two

(2)

ways

by

which

members

of

the

board

can

be

granted

compensation

apart

from

reasonable

per

diems:

(1)

when

there

is

a

provision

in

the

by-laws

fixing

their

compensation;

and

(2)

when

the

stockholders

representing

a

majority

of

the

outstanding

capital

stock

at

a

regular

or

special

stockholders'

meeting

agree

to

give

it

to

them.

The

proscription,

however,

against

granting

compensation

to

directors/trustees

of

a

corporation

is

not

a

sweeping

rule.

Worthy

of

note

is

the

clear

phraseology

of

Section

30

which

states:

.

.

.

[T]he

directors

shall

not

receive

any

compensation,

as

such

directors

.

.

.

The

phrase

as

such

directors

is

not

without

significance

for

it

delimits

the

scope

of

the

prohibition

to

compensation

given

to

them

for

services

performed

purely

in

their

capacity

as

directors

or

trustees.

The

unambiguous

implication

is

that

members

of

the

board

may

receive

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 1

CORPORATION LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

compensation, in addition to reasonable per diems; when they render

services to the corporation in a capacity other than as directors/

trustees. In the case at bench, Resolution No. 48, s. 1986 granted

monthly compensation to private respondents not in their capacity as

members of the board, but rather as officers of the corporation, more

particularly as Chairman, Vice Chairman, Treasurer and Secretary of

Western Institute of Technology. Thus, the prohibition with respect to

granting compensation to corporate directors/trustees as such under

Section 30 is not violated in this particular case.

Additional Matters:

Re March 30 vs June 1: The Court held that prosecution failed to

present the whole minutes of the BoTs regular meeting. Had it

included the complete minutes, it can be seen that Resolution No. 48

was actually passed on March 30. And even though the compensation

was not expressly mentioned in the Agenda, the minutes disclosed that

the Resolution was passed on March 30.

Re Petitioners claim that it is a derivative suit: SC held in the negative.

It was merely an appeal on the civil aspect of Criminal Cases filed with

the RTC. Among the basic requirements for a derivative suit to prosper

is that the minority shareholder who is suing for and on behalf of the

corporation must allege in his complaint before the proper forum that

he is suing on a derivative cause of action on behalf of the corporation

and all other shareholders similarly situated who wish to join. This is

necessary to vest jurisdiction upon the tribunal in line with the rule

that it is the allegations in the complaint that vests jurisdiction upon

the court or quasi-judicial body concerned over the subject matter and

nature of the action. This was not complied with by the petitioners

either in their complaint before the court a quo nor in the instant

petition.

SANTOS vs. NLRC

G.R. No. 101699 March 13, 1996

FACTS:

Private respondent Melvin D. Millena was hired to be the project

accountant for MMDC's (Mana Mining and Development Corporation)

mining operations in Gatbo, Bacon, Sorsogon. On 12 August 1986,

private respondent sent to Mr. Gil Abao, the MMDC corporate

treasurer, a memorandum calling the latter's attention to the failure of

the company to comply with the withholding tax requirements of, and

to make the corresponding monthly remittances to, the Bureau of

Internal Revenue ("BIR") on account of delayed payments of accrued

salaries to the company's laborers and employees.

In a letter, Abao advised private respondent that the board had

decided that it would be useless to continue operations in Sorsogon

taking into consideration that it was already rainy season and that the

peace and order condition therein had deteriorated. Abao also said

that the company will stop production until the advent of the dry

season, and until the insurgency problem clears. It will undertake only

necessary maintenance and repair work and will keep our overhead

down to the minimum manageable level. Until it resumes full-scale

operations, it will not need a project accountant as there will be very

little paper work at the site, which can be easily handled at Makati.

Private respondent expressed "shock" over the termination of his

employment. He complained that he would not have resigned from the

Sycip, Gorres & Velayo accounting firm, where he was already a senior

staff auditor, had it not been for the assurance of a "continuous job" by

MMDC's Eng. Rodillano E. Velasquez. Private respondent requested that

he be reimbursed the "advances" he had made for the company and be

paid his "accrued salaries/claims." Since the claim was not heeded, he

filed with the NLRC a complaint for illegal dismissal, unpaid salaries,

13th month pay, overtime pay, separation pay and incentive leave pay

against MMDC and its two top officials, namely, herein petitioner

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 2

CORPORATION LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

Benjamin A. Santos (the President) and Rodillano A. Velasquez (the

executive vice-president).

The Labor Arbiter found no valid cause for the dismissal of Millena. The

company and its co-respondents appealed. NLRC affirmed LAs

decision. It held that the reasons relied upon by MMDC and its co-

respondents in the dismissal of Millena, i.e., the rainy season,

deteriorating peace and order situation and little paperwork, were "not

causes mentioned under Article 282 of the Labor Code of the

Philippines" and that Millena, being a regular employee, was "shielded

by the tenurial clause mandated under the law."

A writ of execution correspondingly issued; however, it was returned

unsatisfied for the failure of the sheriff to locate the offices of the

corporation in the address indicated. Another writ of execution and an

order of garnishment was thereupon served on petitioner at his

residence. petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration of the NLRC's

resolution along with a prayer for the quashal of the writ of execution

and order of garnishment. He averred that he had never received any

notice, summons or even a copy of the complaint; hence, he said, the

Labor Arbiter at no time had acquired jurisdiction over him.

Petitioner argues that public respondents have gravely abused their

discretion "in finding petitioner solidarily liable with MMDC even in the

absence of bad faith and malice on his part."

ISSUE:

WON petitioner can be held personally liable.

HELD:

No. A corporation is a juridical entity with legal personality separate

and distinct from those acting for and in its behalf and, in general, from

the people comprising it. The rule is that obligations incurred by the

corporation, acting through its directors, officers and employees, are its

sole liabilities. Nevertheless, being a mere fiction of law, peculiar

situations or valid grounds can exist to warrant, albeit done sparingly,

the

disregard

of

its

independent

being

and

the

lifting

of

the

corporate

veil.

As

a

rule,

this

situation

might

arise

when

a

corporation

is

used

to

evade

a

just

and

due

obligation

or

to

justify

a

wrong,

to

shield

or

perpetrate

fraud,

to

carry

out

similar

other

unjustifiable

aims

or

intentions,

or

as

a

subterfuge

to

commit

injustice

and

so

circumvent

the

law.

In

Tramat

Mercantile,

Inc.,

vs.

Court

of

Appeals,

the

Court

has

collated

the

settled

instances

when,

without

necessarily

piercing

the

veil

of

corporate

fiction,

personal

civil

liability

can

also

be

said

to

lawfully

attach

to

a

corporate

director,

trustee

or

officer;

to

wit:

When

"(1)He

assents

(a)

to

a

patently

unlawful

act

of

the

corporation,

or

(b)

for

bad

faith

or

gross

negligence

in

directing

its

affairs,

or

(c)

for

conflict

of

interest,

resulting

in

damages

to

the

corporation,

its

stockholders

or

other

persons;

"

(2)He

consents

to

the

issuance

of

watered

stocks

or

who,

having

knowledge

thereof,

does

not

forthwith

file

with

the

corporate

secretary

his

written

objection

thereto;

"

(3)He

agrees

to

hold

himself

personally

and

solidarily

liable

with

the

corporation;

or

"

(4)He

is

made,

by

a

specific

provision

of

law,

to

personally

answer

for

his

corporate

action."

The

case

of

petitioner

is

way

off

these

exceptional

instances.

It

is

not

even

shown

that

petitioner

has

had

a

direct

hand

in

the

dismissal

of

private

respondent

enough

to

attribute

to

him

(petitioner)

a

patently

unlawful

act

while

acting

for

the

corporation.

Neither

can

Article

289

of

the

Labor

Code

be

applied

since

this

law

specifically

refers

only

to

the

imposition

of

penalties

under

the

Code.

It

is

undisputed

that

the

termination

of

petitioner's

employment

has,

instead,

been

due,

collectively,

to

the

need

for

a

further

mitigation

of

losses,

the

onset

of

the

rainy

season,

the

insurgency

problem

in

Sorsogon

and

the

lack

of

funds

to

further

support

the

mining

operation

in

Gatbo.

There

appears

to

be

no

evidence

on

record

that

he

acted

maliciously

or

in

bad

faith

in

terminating

the

services

of

private

respondent.

His

act,

therefore,

was

within

the

scope

of

his

authority

and

was

a

corporate

act.

"It

is

basic

that

a

corporation

is

invested

by

law

with

a

personality

separate

and

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 3

CORPORATION LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

distinct from those of the persons composing it as well as from that of

any other legal entity to which it may be related. Mere ownership by a

single stockholder or by another corporation of all or nearly all of the

capital stock of a corporation is not of itself sufficient ground for

disregarding the separate corporate personality.

SPOUSES ROBERTO & EVELYN DAVID and COORDINATED GROUP,

INC., vs. CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY AND ARBITRATION

COMMISSION and SPS. NARCISO & AIDA QUIAMBAO

G.R. No. 159795 - July 30, 2004.

FACTS:

Petitioner COORDINATED GROUP, INC. (CGI) is a corporation engaged

in the construction business, with petitioner-spouses ROBERTO and

EVELYN DAVID as its President and Treasurer, respectively. The

records reveal that respondent-spouses NARCISO and AIDA QUIAMBAO

engaged the services of petitioner CGI to design and construct a five-

storey concrete office/residential building on their land in Tondo,

Manila. The Design/Build Contract of the parties provided that: (a)

petitioner CGI shall prepare the working drawings for the construction

project; (b) respondents shall pay petitioner CGI the sum of

P7,309,821.51 for the construction of the building, including the costs

of labor, materials and equipment, and P200,000.00 for the cost of the

design; and (c) the construction of the building shall be completed

within 9 months after securing the building permit.

The completion of the construction was initially scheduled on or before

July 16, 1998 but was extended to November 15, 1998 upon agreement

of the parties. It appears, however, that petitioners failed to follow the

specifications and plans as previously agreed upon. Respondents

demanded the correction of the errors but petitioners failed to act on

their complaint. Consequently, respondents rescinded the contract

after paying 74.84% of the cost of construction.

Respondents then engaged the services of another contractor, RRA and

Associates, to inspect the project and assess the actual accomplishment

of petitioners in the construction of the building. It was found that

petitioners revised and deviated from the structural plan of the

building without notice to or approval by the respondents.

Respondents filed a case for breach of contract against petitioners

before the RTC of Manila. At the pre-trial conference, the parties agreed

to submit the case for arbitration to the CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

ARBITRATION COMMISSION (CIAC). Respondents filed a request for

arbitration with the CIAC and nominated Atty. Custodio O. Parlade as

arbitrator. (remember PARLADE? ADR? J) Atty. Parlade was

appointed by the CIAC as sole arbitrator to resolve the dispute. With

the agreement of the parties, Atty. Parlade designated Engr. Loreto C.

Aquino to assist him in assessing the technical aspect of the case. The

RTC of Manila then dismissed the case and transmitted its records to

the CIAC.

Arbitration decision: in favor of Quiambaos. After several

computations, the award in the arbitration proceedings were credited

to the payments already made to CGI, the sum was more or less 10M.

and then 10M less the payments due to CGI (that is 80% of work

accomplishment) plus cost of materials, the total award to be paid to

the Quambaos by the respondents jointly and severally was more or

less 4.1M plus 6%/12% per annum until it is paid. (own words ko to

and rounded off, para mas madali.)

CA decision: affirmed but deleted the lost rental.

Petitioners filed a petition for review and contended among others that

I.THERE WAS NO BASIS, IN FACT AND IN LAW, TO ALLOW

RESPONDENTS TO UNILATERALLY RESCIND THE DESIGN/BUILT

CONTRACT, AFTER PETITIONERS HAVE (SIC) SUBSTANTIALLY

PERFORMED THEIR OBLIGATION UNDER THE SAID CONTRACT and II.

IN FINDING PETITIONERS JOINTLY AND SEVERALLY LIABLE WITH

CO-PETITIONER COORDINATED (GROUP, INC.), IN CLEAR VIOLATION

OF THE DOCTRINE OF SEPARATE JURIDICAL PERSONALITY

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 4

CORPORATION LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

ISSUE:

1. WON

the

rescission

of

contract

was

justified

2. WON

petitioner-spouses

as

corporate

officers

were

grossly

negligent

in

ordering

the

revisions

on

the

construction

plan

without

the

knowledge

and

consent

of

the

respondent-spouses.

HELD:

1. YES.

E.O.

No.

1008

or

the

Constructions

Industry

Arbitration

Law

vests

on

the

Construction

Industry

Arbitration

Commission

(CIAC)

original

and

exclusive

jurisdiction

over

disputes

arising

from

or

connected

with

construction

contracts

entered

into

by

parties

who

have

agreed

to

submit

their

case

to

voluntary

arbitration.

Section

19

of

E.O.

No.

1008

provides

that

its

arbitral

award

shall

be

appealable

to

the

Supreme

Court

only

on

questions

of

law.

There

is

a

question

of

law

when

the

doubt

or

difference

in

a

given

case

arises

as

to

what

the

law

is

on

a

certain

set

of

facts,

and

there

is

a

question

of

fact

when

the

doubt

arises

as

to

the

truth

or

falsity

of

the

alleged

facts.

Thus,

for

a

question

to

be

one

of

law,

it

must

not

involve

an

examination

of

the

probative

value

of

the

evidence

presented

by

the

parties

and

there

must

be

no

doubt

as

to

the

veracity

or

falsehood

of

the

facts

alleged.

In

the

case

at

bar,

it

is

readily

apparent

that

petitioners

are

raising

questions

of

fact.

In

their

first

assigned

error,

petitioners

claim

that

at

the

time

of

rescission,

they

had

completed

80%

of

the

construction

work

and

still

have

15

days

to

finish

the

project.

They

likewise

insist

that

they

constructed

the

building

in

accordance

with

the

contract

and

any

modification

on

the

plan

was

with

the

consent

of

the

respondents.

However,

these

claims

were

refuted

by

evidences

w/c

was

taken

during

the

arbitration

proceedings

and

even

upheld

by

the

CA

(among

them

were

as

follows:

there

were

deviations

from

the

approved

plans

and

specifications such as the building was not vertically plumbed,

misaligned walls, low head clearances, addl columns at the basement

and the first floor w.c restricted the use of basement as parking area,

construction of cistern tank w/c capacity should be 10000 galloons but

what was constructed was less than the supposed capacity, etc.). The

only defense of the petitioner was that these were only punch-list items

w/c could be corrected prior to completion and the turnover of the

building had the contract was not rescinded. Punch listing means that

the contractor will list all major and minor defects and rectifies them

before the turnover of the project to the owner. After all defects had

been arranged, the project is now turned over to the owner. For this

particular project, no turn over was made by the contractor to the

owner yet.

MAIN POINT: these revisions were not made with the consent of

the Quiambaos. (kaya nga sila nagrescind) The Contract

specifically provided in Article II that "the CONTRACTOR shall

submit to the OWNER all designs for the OWNER'S approval." And

this is a clear breach of the contract.

Granting the arguments of the Respondents (herein petitioners) that

the observed defects in the Building could be corrected before turn-

over and acceptance of the Building if CGI had been allowed to

complete its construction, the construction of additional columns, the

construction of the Building such that part of it is outside the property

line established a sufficient legal and factual basis for the decision of

the Quiambaos to terminate the Contract. The fact that 5 out of 9 of the

concrete samples subjected to a core test, and 8 out of 18 deformed

reinforcing steel bar specifics subjected to physical tests failed the tests

and the under-design of the cistern was established after the Contract

was terminated also served to confirm the justified suspicion of the

Quiambaos that the Building was defective or was not constructed

according to approved plans and specifications. These are technical

findings of fact made by expert witnesses and affirmed by the

arbitrator.

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 5

CORPORATION LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

2.

Yes.

As

a

general

rule,

the

officers

of

a

corporation

are

not

personally

liable

for

their

official

acts

unless

it

is

shown

that

they

have

exceeded

their

authority.

However,

the

personal

liability

of

a

corporate

director,

trustee

or

officer,

along

with

corporation,

may

so

validly

attach

when

he

assents

to

a

patently

unlawful

act

of

the

corporation

or

for

bad

faith

or

gross

negligence

in

directing

its

affairs.

Following

the

findings

of

public

respondent

(CIAC)

as

when

CGI/DAVIDS

were

asked

whether

the

Building

was

underdesigned

considering

the

poor

quality

of

the

soil,

Engr.

Villasenor

defended

his

structural

design

as

adequate.

He

admitted

that

the

revision

of

the

plans

which

resulted

in

the

construction

of

additional

columns

was

in

pursuance

of

the

request

of

Engr.David

to

revise

the

structural

plans

to

provide

for

a

significant

reduction

of

the

cost

of

construction.

When

Engr.

David

was

asked

for

the

justification

for

the

revision

of

the

plans,

he

confirmed

that

he

wanted

to

reduce

the

cost

of

construction.

.

.

.

Clearly,

the

case

at

bar

does

not

raise

any

genuine

issue

of

law.

Hence

the

petition

was

dismissed

and

ruling

of

arbitrator

was

affirmed.

Why?

(baka

itanong)

We

reiterate

the

rule

that

factual

findings

of

construction

arbitrators

are

final

and

conclusive

and

not

reviewable

by

this

Court

on

appeal,

except

when

the

petitioner

proves

affirmatively

that:

(1)

the

award

was

procured

by

corruption,

fraud

or

other

undue

means;

(2)

there

was

evident

partiality

or

corruption

of

the

arbitrators

or

of

any

of

them;

(3)

the

arbitrators

were

guilty

of

misconduct

in

refusing

to

postpone

the

hearing

upon

sufficient

cause

shown,

or

in

refusing

to

hear

evidence

pertinent

and

material

to

the

controversy;

(4)

one

or

more

of

the

arbitrators

were

disqualified

to

act

as

such

under

section

nine

of

Republic

Act

No.

876

and

willfully

refrained

from

disclosing

such

disqualifications

or

of

any

other

misbehavior

by

which

the

rights

of

any

party

have

been

materially

prejudiced;

or

(5)

the

arbitrators

exceeded

their

powers,

or

so

imperfectly

executed

them,

that

a

mutual,

final

and

definite

award

upon

the

subject

matter

submitted

to

them

was

not

made.

Petitioners

failed

to

show

that

any

of

these

exceptions

applies

to

the

case

at

bar.

MALAYANG

SAMAHAN

NG

MGA

MANGGAGAWA

SA

M.

GREENFIELD

vs.

RAMOS

G.R.

No.

113907

-

April

20,

2001

FACTS:

Petitioners

allege

that

this

Court

committed

patent

and

palpable

error

in

holding

that

the

respondent

company

officials

cannot

be

held

personally

liable

for

damages

on

account

of

employees

dismissal

because

the

employer

corporation

has

a

personality

separate

and

distinct

from

its

officers

who

merely

acted

as

its

agents

whereas

the

records

clearly

established

that

respondent

company

officers

Saul

Tawil,

Carlos

T.

Javelosa

and

Renato

C.

Puangco

have

caused

the

hasty,

arbitrary

and

unlawful

dismissal

of

petitioners

from

work;

that

as

top

officials

of

the

respondent

company

who

handed

down

the

decision

dismissing

the

petitioners,

they

are

responsible

for

acts

of

unfair

labor

practice;

that

these

respondent

corporate

officers

should

not

be

considered

as

mere

agents

of

the

company

but

the

wrongdoers.

Petitioners

further

contend

that

while

the

case

was

pending

before

the

public

respondents,

the

respondent

company,

in

the

early

part

of

February

1990,

began

removing

its

machineries

and

equipment

from

its

plant

located

at

Merville

Park,

Paranaque

and

began

diverting

jobs

intended

for

the

regular

employees

to

its

sub-contractor/satellite

branches;

that

the

respondent

company

officials

are

also

the

officers

and

incorporators

of

these

satellite

companies

as

shown

in

their

articles

of

incorporation

and

the

general

information

sheet.

They

added

that

during

their

ocular

inspection

of

the

plant

site

of

the

respondent

company,

they

found

that

the

same

is

being

used

by

other

unnamed

business

entities

also

engaged

in

the

manufacture

of

garments.

Petitioners

further

claim

that

the

respondent

company

no

longer

operates

its

plant

site

as

M.

Greenfield

thus

it

will

be

very

difficult

for

them

to

fully

enforce

and

implement

the

courts

decision.

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 6

CORPORATION LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

On the other hand, private respondent company officials Carlos

Javelosa and Remedios Caoleng, in their Comment, state that

considering that petitioners admitted having knowledge of the fact that

private respondent officers are also holding key positions in the alleged

satellite companies, they should have presented the pertinent evidence

with the public respondents; thus it is too late for petitioners to require

this Court to admit and evaluate evidence not presented during the

trial; that the supposed proof of satellite companies hardly constitute

newly discovered evidence.

ISSUE:

WON respondent company officials should be made personally liable

for damages

HELD:

Petitioners contention that respondent company officials should be

made personally liable for damages on account of petitioners dismissal

is not impressed with merit. A corporation is a juridical entity with

legal personality separate and distinct from those acting for and in its

behalf and, in general from the people comprising it. The rule is that

obligations incurred by the corporation, acting through its directors,

officers and employees, are its sole liabilities. True, solidary liabilities

may at times be incurred but only when exceptional

circumstances warrant such as, generally, in the following cases:

1. When directors and trustees, or, in appropriate cases, the

officers of a corporation-

a. Vote for or assent to patently unlawful acts of

the corporation;

b. act in bad faith or with gross negligence in directing the

corporate affairs;

c. are guilty of conflict of interest to the prejudice of the

corporation, its stockholders or members, and other

persons.

2. When a director or officer has consented to the issuance of

watered stocks or who, having knowledge thereof, did

not forthwith file with the corporate secretary his

written objection thereto

3. When a director, trustee or officer has contractually agreed or

stipulated to hold himself personally and solidarily liable

with the Corporation.

4. When a director, trustee or officer is made, by specific

provision of law, personally liable for his corporate

action.

In labor cases, particularly, the Court has held corporate directors and

officers solidarily liable with the corporation for the termination of

employment of corporate employees done with malice or in bad faith.

Bad faith or negligence is a question of fact and is evidentiary. It has

been held that bad faith does not connote bad judgement or negligence;

it imports a dishonest purpose or some moral obliquity and conscious

doing of wrong; it means breach of a known duty thru some motive or

interest or ill will; it partakes of the nature of fraud.

Petitioners claim that the jobs intended for the respondent companys

regular employees were diverted to its satellite companies where the

respondent company officers are holding key positions is not

substantiated and was raised for the first time in this motion for

reconsideration. Even assuming that the respondent company officials

are also officers and incorporators of the satellite companies, such

circumstance does not in itself amount to fraud. The documents

attached to petitioners motion for reconsideration show that these

satellite companies were established prior to the filing of petitioners

complaint against private respondents with the Department of Labor

and Employment on September 6, 1989 and that these corporations

have different sets of incorporators aside from the respondent officers

and are holding their principal offices at different locations. Substantial

identity of incorporators between respondent company and these

satellite companies does not necessarily imply fraud. In such a case,

respondent companys corporate personality remains inviolable.

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 7

CORPORATION LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

Although

there

were

earlier

decisions

of

this

Court

in

labor

cases

where

corporate

officers

were

held

to

be

personally

liable

for

the

payment

of

wages

and

other

money

claims

to

its

employees,

we

find

those

rulings

inapplicable

to

this

case.

PRIME

WHITE

CEMENT

CORPORATION

vs.

IAC

G.R.

No.

68555

March

19,

1993

FACTS:

On

July

16,

1969,

Alejandro

Te

and

Prime

White

Cement

Corp.

thru

its

President

Zosimo

Falcon

and

its

Chairman

of

the

Board

Justo

Trazo

entered

into

a

dealership

agreement

whereby:

a.

b.

c.

d.

They will act as exclusive dealer of Prime Whites cement

product in the entire Mindanao area for 5 years,

Prime White shall supply and sell to Te 20,000 cement

bags per month,

They shall pay P9.70 per bag, and

They shall open with any bank a letter of credit and upon

the certification of the boat captain on the bill of lading

that the goods were already loaded on board the vessel,

the bank shall release the amount as payment for the

goods to be shipped.

Relying

heavily

on

the

dealership

agreement,

Te

entered

into

a

contract

to

supply

with

several

hardware

stores

and

sell

to

them

20,000

allocated

cement

bags

by

September

1970.

Thereafter,

Te

informed

Prime

Corp.

that

he

is

preparing

to

open

another

letter

of

credit

to

cover

the

delivery

for

September

1970.

However,

the

corporations

board

imposed

the

following

conditions:

a.

b.

c.

d.

Delivery shall commence on November 1970,

Only 8,000 bags per month for 3 months will be delivered,

The price per bag is increased to P13.30 and subject to

unilateral readjustment by the corp.

The place of delivery shall be Asturias,

e.

f.

The letter of credit may be opened only with Prudential

Bank-Makati branch,

Payment shall be made in advance.

They

made

several

demands

against

Prime

White

Corp.

to

comply

with

the

dealership

agreement

but

the

latter

refused

forcing

Te

to

cancel

his

contract

to

supply

with

the

hardwares.

Prime

white

entered

into

an

exclusive

dealership

agreement

with

Napoleon

Co.

Hence,

the

suit.

RTC:

Ruled

in

favour

of

Te.

CA:

Affirmed

RTCs

decision.

ISSUE:

WON

the

dealership

agreement

is

valid

and

enforceable

contract.

RULING:

NO.

Under

the

Corporation

Law,

which

was

then

in

force

at

the

time

this

case

arose,

as

well

as

under

the

present

Corporation

Code,

all

corporate

powers

shall

be

exercised

by

the

Board

of

Directors,

except

as

otherwise

provided

by

law.

Although

it

cannot

completely

abdicate

its

power

and

responsibility

to

act

for

the

juridical

entity,

the

Board

may

expressly

delegate

specific

powers

to

its

President

or

any

of

its

officers.

In

the

absence

of

such

express

delegation,

a

contract

entered

into

by

its

President,

on

behalf

of

the

corporation,

may

still

bind

the

corporation

if

the

board

should

ratify

the

same

expressly

or

impliedly.

Implied

ratification

may

take

various

forms

-

like

silence

or

acquiescence;

by

acts

showing

approval

or

adoption

of

the

contract;

or

by

acceptance

and

retention

of

benefits

flowing

therefrom.

Furthermore,

even

in

the

absence

of

express

or

implied

authority

by

ratification,

the

President

as

such

may,

as

a

general

rule,

bind

the

corporation

by

a

contract

in

the

ordinary

course

of

business,

provided

the

same

is

reasonable

under

the

circumstances.

These

rules

are

basic,

but

are

all

general

and

thus

quite

flexible.

They

apply

where

the

President

or

other

officer,

purportedly

acting

for

the

corporation,

is

dealing

with

a

third

person,

i.e.,

person

outside

the

corporation.

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 8

CORPORATION LAW CASE DIGESTS

3C & 3S ATTY. CARLO BUSMENTE

RULE IN CASE OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST. A director of a

corporation holds a position of trust and as such, he owes a duty of

loyalty to his corporation. In case his interests conflict with those of the

corporation, he cannot sacrifice the latter to his own advantage and

benefit. As corporate managers, directors are committed to seek the

maximum amount of profits for the corporation.

DEALINGS OF DIRECTORS, TRUSTEES OR OFFICERS WITH THE

CORPORATION; RULE. A director's contract with his corporation is

not in all instances void or voidable. If the contract is fair and

reasonable under the circumstances, it may be ratified by the

stockholders provided a full disclosure of his adverse interest is made

as provided in Section 32 of the Corporation Code.

however, That the contract is fair and reasonable under the

circumstances."

In the light of the circumstances of this case, it is to Us quite clear that

he was guilty of disloyalty to the corporation; he was attempting in

effect, to enrich himself at the expense of the corporation. There is no

showing that the stockholders ratified the "dealership agreement" or

that they were fully aware of its provisions. The contract was therefore

not valid and this Court cannot allow him to reap the fruits of his

disloyalty.

"SEC. 32.Dealings of directors, trustees or officers with the

corporation. A contract of the corporation with one or more of its

directors or trustees or officers is voidable, at the option of such

corporation, unless all the following conditions are present:

1. 1.That the presence of such director or trustee in the board

meeting in which the contract was approved was

not necessary to constitute a quorum for such

meeting;

2. 2.That the vote of such director or trustee was not necessary

for the approval of the contract;

3. 3.That the contract is fair and reasonable under the

circumstances; and

4. 4.That in the case of an officer, the contract with the officer

has been previously authorized by the Board of

Directors

Where any of the first two conditions set forth in the preceding

paragraph is absent, in the case of a contract with a director or

trustee, such contract may be ratified by the vote of the stockholders

representing at least two-thirds (2/3) of the outstanding capital stock

or of two-thirds (2/3) of the members in a meeting called for the

purpose: Provided, That full disclosure of the adverse interest of the

directors or trustees involved is made at such meeting: Provided,

CORPO CASE DIGESTS 3C & 3S || 9

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Corporation Notes - Law3ADokument51 SeitenCorporation Notes - Law3ATannaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Table of Comparison Writs of Habeas Corpus, Amparo, Habeas Data, and KalikasanDokument7 SeitenTable of Comparison Writs of Habeas Corpus, Amparo, Habeas Data, and KalikasanJayvee Robias100% (5)

- Citizenship ReacquisitionDokument8 SeitenCitizenship ReacquisitionSui100% (2)

- Business Law 2nd EditionDokument651 SeitenBusiness Law 2nd EditionDixie CheeloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Procedure ReviewerDokument51 SeitenCriminal Procedure ReviewerJingJing Romero94% (156)

- Election Law Case DigestDokument29 SeitenElection Law Case DigestmagdalooNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Law of Torts 2018Dokument200 SeitenThe Law of Torts 2018RachelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benedict On Admiralty - PracticeDokument303 SeitenBenedict On Admiralty - PracticeRebel XNoch keine Bewertungen

- Special Rules of Court On ADRDokument39 SeitenSpecial Rules of Court On ADRClaire RoxasNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIVREV Quiz6PropertyDokument3 SeitenCIVREV Quiz6PropertyChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Third Party Funding in ArbitrationDokument155 SeitenThird Party Funding in ArbitrationKendista Wantah100% (2)

- Civpro (Rev)Dokument102 SeitenCivpro (Rev)ivanmendezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Quamto 2016Dokument63 SeitenLabor Quamto 2016Ann HopeloveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conde v. AbayaDokument2 SeitenConde v. AbayaChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest Country Bankers V LagmanDokument2 SeitenDigest Country Bankers V LagmanAleph JirehNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4S - CIVIL LAW REVIEW Case Digests - Persons&Family Relations - Set1Dokument32 Seiten4S - CIVIL LAW REVIEW Case Digests - Persons&Family Relations - Set1Chezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law Book 1 Articles 11-20Dokument51 SeitenCriminal Law Book 1 Articles 11-20Dianne MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annulment of Judgment, Annulment of Contract With TRO and DamagesDokument13 SeitenAnnulment of Judgment, Annulment of Contract With TRO and DamagesRamon Carlos PalomaresNoch keine Bewertungen

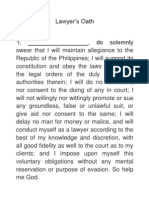

- Lawyer's OathDokument1 SeiteLawyer's OathKukoy PaktoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- LOCSIN vs. CADokument2 SeitenLOCSIN vs. CAChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- 148 Metropolitan Bank and Trust Co. V Junnel's Marketing CorpDokument3 Seiten148 Metropolitan Bank and Trust Co. V Junnel's Marketing CorpBeata CarolinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. UmaliDokument2 SeitenPeople vs. UmaliChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biaco V Philippine Countryside Rural BankDokument20 SeitenBiaco V Philippine Countryside Rural BankClaudine Mae G. TeodoroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bank of Bihar V Damodar Prasad - Case AnalysisDokument16 SeitenBank of Bihar V Damodar Prasad - Case AnalysisShreya Ghosh Dastidar33% (3)

- Digest - Occena vs. Jabson and Sesbreno v. CADokument3 SeitenDigest - Occena vs. Jabson and Sesbreno v. CAKê MilanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law ReviewDokument10 SeitenLabor Law ReviewChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argana Case Timeline PoDokument4 SeitenArgana Case Timeline PoChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law ReviewDokument10 SeitenLabor Law ReviewChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rabadilla Vs CADokument2 SeitenRabadilla Vs CAChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence Digests Batch 5Dokument18 SeitenEvidence Digests Batch 5Chezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- GeneralDokument1 SeiteGeneralChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment in LegtechDokument8 SeitenAssignment in LegtechChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corpo 1112Dokument1 SeiteCorpo 1112Chezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corpo 111Dokument1 SeiteCorpo 111Chezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classes of MovablesDokument4 SeitenClasses of MovablesChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civ1 Bar2017Dokument3 SeitenCiv1 Bar2017Chezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corpo 111Dokument1 SeiteCorpo 111Chezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- BaselDokument1 SeiteBaselChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- I. General Principles: Determines The Competence of TheDokument1 SeiteI. General Principles: Determines The Competence of TheNikko SterlingNoch keine Bewertungen

- BaselDokument1 SeiteBaselChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDokument14 SeitenBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRIMREV Art 114 202Dokument24 SeitenCRIMREV Art 114 202Chezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Doctrines PDFDokument27 SeitenCase Doctrines PDFChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- DefenseDokument3 SeitenDefenseChezca MargretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facts:: G.R. No. 161720 November 22, 2005 HEIRS OF FLORES RESTAR Petitioners, vs. Heirs of Dolores R. Cichon RespondentsDokument3 SeitenFacts:: G.R. No. 161720 November 22, 2005 HEIRS OF FLORES RESTAR Petitioners, vs. Heirs of Dolores R. Cichon RespondentssophiabarnacheaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIAA vs. City of PasayDokument56 SeitenMIAA vs. City of PasayKristine MagbojosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toyota Shaw Inc. Vs CA 244 Scra 320Dokument9 SeitenToyota Shaw Inc. Vs CA 244 Scra 320Anonymous b7mapUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tort Law: THE Study of LawDokument3 SeitenTort Law: THE Study of LawDiana IlieşNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06 United States vs. Ang Tang HoDokument13 Seiten06 United States vs. Ang Tang HoCarlota Nicolas VillaromanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases On The Comprehensive Agrarian Reform LawDokument10 SeitenCases On The Comprehensive Agrarian Reform LawJennifer Marie Columna BorbonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge 149Dokument45 SeitenGe 149John Louie CarmenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spouses Layos v. Fil-Estate Golf And20170403-911-1fr6p5n PDFDokument26 SeitenSpouses Layos v. Fil-Estate Golf And20170403-911-1fr6p5n PDFJam NagamoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Kapila Hingorani CaseDokument39 Seiten10 Kapila Hingorani CaseAshutosh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torres Vs RodellasDokument17 SeitenTorres Vs RodellasZeusKimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raymundo vs. Vda. de SuarezDokument10 SeitenRaymundo vs. Vda. de SuarezNash LedesmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon Cases IVDokument370 SeitenOblicon Cases IVMaurice PinayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflicts CasesDokument239 SeitenConflicts CasesArt ManlongatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unauthorized Contracts Are Governed by Article 1317 and The Principles of Agency in Title X of This BookDokument12 SeitenUnauthorized Contracts Are Governed by Article 1317 and The Principles of Agency in Title X of This Bookluis capulongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glene. Property Case Digest.Dokument10 SeitenGlene. Property Case Digest.Master GanNoch keine Bewertungen

- McKee vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtDokument32 SeitenMcKee vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtMrln VloriaNoch keine Bewertungen